Abstract

In this paper, we investigate possible sources of declining economic growth in Italy beginning near the middle of the 1990s. A long-term data analysis suggests that the poor performance of the Italian economy cannot be blamed on an unfortunate business cycle contingency. Other countries of the euro area have shown better performance, and the macroeconomic data indicate that the Italian economy has not grown at the same rate as these other European economies. We investigate the sources of economic fluctuations in Italy by applying the business cycle accounting procedure introduced by Chari et al. (Econometrica 75(3):781–836, 2007). We analyze the relative importance of efficiency, labor, investment and government wedges for business cycles in Italy during the 1982–2008 period. We find that individual wedges have played different roles during this period; however, the efficiency wedge is shown to be the factor most responsible for the stagnation phase that began in approximately 1995. Our findings also show that the decline in labor market distortions that occurred in Italy during the 1990s alleviated the stagnation effect somewhat and prevented an even more abrupt slowdown in per capita output growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Excluding the 2009 crisis, from 2000 to 2008, the average growth rate in Italy was equal to 1 % each year.

Moving from an average growth of 1.9 % to an average growth of 1.3 %.

Following Arpaia et al. (2009), figures for the labor income share are obtained using inter-sectoral data taken from the EU KLEMS database. The value 0.58 corresponds to the average labor share during the 1982–2008 period.

Population refers to all individuals 15–64 years in age.

This value is equal to the average hours worked in a quarter as a fraction of the total quarterly hours for the 1982–2008 period.

Alternatively, we can recover the government wedge as a residual from the resources constraint (6) by using data for per capita consumption, \(c_{t}\), per capita investment, \(x_{t}\) and per capita output, \(y_{t}\).

In the computation, we define \(\xi _{t+1}= Q\varepsilon _{t+1}\), where \(Q\) is a lower triangular matrix and \(\varepsilon _{t+1}\) is a white noise. This guarantees that the estimated matrix, \(V = QQ^{\prime }\), is positive semi-definite.

Consistent with the balanced growth path equilibrium implied by our model, the trend is assumed to be equal to the calibrated quarterly growth rate of technology, \(\gamma \).

Details about the sources of data and transformations used in our analysis are provided in the “Appendix”.

All variables are expressed in per capita values.

We take the yearly average because data for effective tax rates are available only at annual frequencies.

The authors also show that this difference is more pronounced for firms that introduce product innovation compared to firms that adopt process innovation.

For example, the authors show that the lending-deposit spread rate begins to decline substantially 4 years after deregulation in 1983.

The Conference Board Total Economy Database, January 2010, http://www.conference-board.org/economics/database.cfm.

References

Ahearne A, Kydland F, Wynne MA (2006) Ireland’s great depression. Econ Soc Rev 37(2):215–243

Arpaia A, Perez E, Pichelmann K (2009) Understanding labour income share dynamics in Europe. MPRA Working Papers 379, University Library of Munich

Bernanke B, Gertler M (1989) Agency costs, net worth, and business fluctuations. Am Econ Rev 79(1):14–31

Bernanke BS, Gertler M, Gilchrist S (1999) The financial accelerator in a quantitative business cycle framework. In: Taylor JB, Woodford M (eds) Handbook of macroeconomics, handbook of macroeconomics, vol 1, chap 21. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 1341–1393

Blanchard O (2004) The economic future of Europe. J Econ Perspect 18(4):3–26

Blanchard O, Landier A (2002) The perverse effects of partial labour market reform: fixed-term contracts in france. Econ J 112(480):F214–F244

Boeri T, Garibaldi P (2007) Two tier reforms of employment protection: a honeymoon effect? Econ J 117(521):357–385

Canova F (2007) Methods for applied macroeconomic research. Princeton Univeristy Press, Princeton

Carlstrom CT, Fuerst TS (1997) Agency costs, net worth, and business fluctuations: a computable general equilibrium analysis. Am Econ Rev 87(5):893–910

Chari VV, Kehoe PJ, McGrattan ER (2007) Business cycle accounting. Econometrica 75(3):781–836

Cipollone P, Guelfi A (2006) The value of flexible contracts: evidence from an Italian panel of industrial firms. Bank of Italy Economic Research Paper 583

Cottarelli C, Ferri G, Generale A (1995) Bank lending rates and financial structure in Italy: a case study. IMF Staff Pap 42(3):670–700

Daveri F, Jona-Lasinio C (2005) Italy’s decline: getting the facts right. Giornale degli Economisti 64(4):365–410

Dew-Becker I, Gordon R (2012) The role of labor-market changes in the slowdown of european productivity growth. Rev Econ Inst 3(2)

Fachin S, Gavosto A (2010) Trends of labour productivity in Italy: a study with panel co-integration methods. Int J Manpower 31(7):755–769

Iona Lasinio C, Vallanti G (2011) Reforms, labour market functioning and productivity dynamics: a sectoral analysis for italy. Working Papers LuissLab 1193, Dipartimento di Economia e Finanza, LUISS Guido Carli

Kersting EK (2008) The 1980s recession in the UK: a business cycle accounting perspective. Rev Econ Dyn 11(1):179–191

Kondeas A, Caudill SB, Gropper D, Raymond J (2008) Deregulation and productivity changes in banking: evidence from European unification. Appl Financ Econ Lett 4(3):193–197

Lucidi F (2012) Is there a trade-off between labour flexibility and productivity growth? Some evidence from italian firms. In: Addabbo T, Solinas G (eds) Non-standard employment and quality of work. AIEL Series in Labour Economics, Physica-Verlag HD, pp 261–285

Martinez-Mongay C (2000) ECFIN’s effective tax rates. Properties and comparisons with other tax indicators. European Economy—Economic Papers 146, Directorate General Economic and Monetary Affairs, European Commission

Parisi ML, Schiantarelli F, Sembenelli A (2006) Productivity, innovation and r &d: micro evidence for italy. Eur Econ Rev 50(8):2037–2061

Prescott EC (2004) Why do Americans work so much more than Europeans? Q Rev 28(1):2–13

van Ark B, O’Mahoney M, Timmer MP (2008) The productivity gap between Europe and the United States: trends and causes. J Econ Perspect 22(1):25–44

Venturini F (2004) The determinants of Italian slowdown: what do the data say? EPKE Working Paper 29. NIESR, London

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the Editor, and one anonymous referee for their useful comments. We also thank Michele Catalano, Asier Mariscal, Antonio Minniti, Paolo Onofri, Davide Raggi, Francesco Serti, and the seminar participants at the ASSET 2010 Annual Meeting in Alicante, and at the IEEE 2011 meeting in Pisa. Francesco Turino is grateful for the financial support from the Spanish Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia and FEDER funds (Project SEJ-2007-62656/ECON). The usual disclaimers apply.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Business cycle accounting

1.1.1 Per capita output

Per capita output \(y_{t} =\) (GDP-Sales taxes)/Woring-age population

where

GDP \(=\) GDP in constant market prices, millions of 2000 euro.

Source: CONISTAT (http://con.istat.it/amerigo/default.asp), series ncfh3.PILFF.D

Sales Taxes \(=\) VAT + net taxes on products + import taxes, millions of 2000 euro.

Source: CONISTAT databank, series nvbh6.IVA.D

Working-age population \(=\) Population aged 15–64

Source: ISTAT.

1.1.2 Per capita worked hours

Per capita worked hours, \(l_{t}=\) (Total quarterly hours actually worked/Working-age population) / (47/4 weeks \(\times \) 112 hours per week)

where

Total quarterly hours actually worked \(=\) Quarterly seasonally adjusted worked hours from CONISTAT, series nvhbb.TOT.D

1.1.3 Per capita investment

Per capita investment, \(x_{t}=\) (Gross fixed investment \(+\) Personal consumption expenditures on durables \(-\) Sales Taxes \(\times \) Share of consumer durables in total consumer spending) /(Working-age population)

where

Gross Fixed Investment \(=\) Gross domestic capital formation, millions of 2000 euro

Source: CONISTAT databank, series ncfh3.INVFLTOF.D

Share of consumer durables in total consumer spending \(=\) (Consumption of durable goods/Total consumption)

Source: CONISTAT databank, series nci5c.DUR.D (Durables) and nci5c.TOTCFN.D (Total), millions of 2000 euro.

1.1.4 Per capita government consumption

Per capita government consumption, \(g_{t}=\) (Goverment Consumption \(+\) Net Exports)/(Working-age population)

where

Government consumption: Government expenditures, millions of 2000 euro

Source: CONISTAT databank, series ncfh3.CONFCOF.D

Net Export \(=\) Net export of goods and services, millions of 2000 euro.

Source: CONISTAT databank, series ncfh3.ESPBSFF.D (Exports), ncfh3.IMPBSFF.D (Imports).

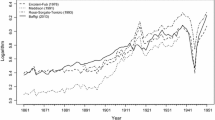

1.2 Figure 1

Per capita GDP for Spain, Italy, France, Germany and the UK from The Conference Board Total Economy Database.Footnote 14

1.3 Table 1

1.3.1 GDP growth

Source: The Conference Board Total Economy Database.

1.3.2 Employment growth

Source: the OECD, LFS database.

1.3.3 Labor productivity growth and components

Source: ISTAT.

1.4 Figure 9

1.4.1 Effective tax wedge

Methodology of Martinez-Mongay (2000) using data from AMECO databank.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Orsi, R., Turino, F. The last fifteen years of stagnation in Italy: a business cycle accounting perspective. Empir Econ 47, 469–494 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-013-0748-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-013-0748-8