Abstract

Abdominal paragangliomas and pheochromocytomas (PPGLs) are rare neuroendocrine tumors of the infradiaphragmatic paraganglia and adrenal medulla, respectively. Although few pathologists outside of endocrine tertiary centers will ever diagnose such a lesion, the tumors are well known through the medical community—possible due to a combination of the sheer rarity, their often-spectacular presentation due to excess catecholamine secretion as well as their unrivaled coupling to constitutional susceptibility gene mutations and hereditary syndromes. All PPGLs are thought to harbor malignant potential, and therefore pose several challenges to the practicing pathologist. Specifically, a responsible diagnostician should recognize both the capacity and limitations of histological, immunohistochemical, and molecular algorithms to pinpoint high risk for future metastatic disease. This focused review aims to provide the surgical pathologist with a condensed update regarding the current strategies available in order to deliver an accurate prognostication of these enigmatic lesions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Abdominal (sympathetic) paragangliomas and pheochromocytomas (PPGLs) are remarkable tumors, not only in terms of clinical presentation with a wide variety of symptoms derived from catecholamine production, but also with regards to the underlying tumor biology and its consequences for patient outcome. We now know that PPGLs constitute the most hereditable of all human tumors, with an established germline susceptibility event in approximately half of the patients [1,2,3,4]. Genetic events underlying the development of these lesions are noted in several different signaling pathways, of which mutations in genes regulating the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle are particularly associated to metastatic disease [5]. Moreover, the former conception of “benign and “malignant” PPGL has now shifted towards a general appreciation that all tumors harbor malignant potential—thereby shifting the focus to a risk stratification approach to identify cases susceptible to future metastatic spread [1]. This focused review aims to cover the current histological, immunohistochemical and molecular approaches to pinpoint PPGLs at risk of dissemination, as well as to highlight the limitations. As parasympathetic paragangliomas of the head and neck region often are non-producing and clinically benign, they are not further discussed here [1].

Epidemiology and Clinical Workup

Traditionally considered a “one in a million” disease, PPGLs have shown a rising incidence during the last 40 years, from 1.4 per million person-years in 1977 to 6.6 in 2015, constituting a 4.8-fold increase [6]. The upsurge is largely attributable to smaller tumors in patients with few/no symptoms, suggesting that an intensified use of clinical imaging techniques might contribute to this increase. Indeed, most PPGLs are diagnosed incidentally following radiological investigations rather than via symptoms of catecholamine excess [7, 8]. PPGLs are usually visualized on conventional CT or MRI scans, although functional modalities such as 123I-meta-iodobenzylguanidine (123I-MIBG) scintigraphy or 68 Ga-DOTATOC positron emission tomography (PET) often are needed to pinpoint the diagnosis [7, 9, 10]. In addition, plasma levels of chromogranin A and metanephrines are usually elevated [7, 11]. When localized to the primary site, cure rates are high if the tumor is surgically resected—however, treatment options for disseminated disease are limited [7, 12].

Diagnostics

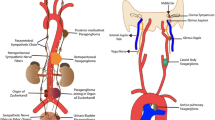

As biopsies are generally not recommended for catecholamine-producing lesions, the diagnosis is typically made postoperatively after routine histopathological examination of the excised tumor [13]. Some baseline gross and microscopic characteristics are detailed in Fig. 1. Histologically, PPGLs often display a nested growth pattern (the so-called zellballen appearance) built-up by chief cells with abundant, basophilic cytoplasm. The tumor cells are usually surrounded by an arborizing network of thin blood vessels and supporting cells (“sustentacular cells”), which are recognizable only if immunohistochemical stains are applied (for example S100 and SOX10) (Fig. 1) [1]. The chief cells are strongly positive for neuroendocrine markers of both first (chromogranin A, synaptophysin) and second generation (ISL1, INSM1), and additional stains that may help distinguish PPGL include GATA3, tyrosine hydroxylase and dopamine beta-hydroxylase (Fig. 1) [1, 14,15,16,17,18]. Keratin expression is almost always absent, except for rare subtypes such as duodenal gangliocytic paragangliomas and cauda equina paragangliomas [14]. When assessing these lesions, the pathologist needs to consider many different aspects, including clinical information, primary tumor site, histology, the extent of invasion, the presence of vascular invasion, as well as the novel TNM staging system as dictated by the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Staging Manual [19, 20]. Interestingly, even though the TNM system for PPGL is newly adopted, the staging seems to reflect the biological properties and clinical outcomes when applied on retrospective materials [21]. In addition, the pathologist could also consider to implement histological scoring algorithms in order to stratify the future risk of metastatic disease [19]. Although all PPGLs are considered to exhibit malignant potential, only 10–15% of pheocromocytomas and between 30 and 50% of abdominal paragangliomas will metastasize to non-chromaffin sites [7]. Therefore, there is a considerable distinction between exhibiting malignant potential and actually exhibiting clinical features of malignancy (i.e., to metastasize). A metastatic pheochromocytoma is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Key gross, microscopic and immunohistochemical findings of PPGLs. A Macroscopic appearance of the resected adrenal with a 10 cm encapsulated pheochromocytoma exhibiting a fleshy cut surface with solid tan-colored areas. B Photomicrograph of hematoxylin–eosin (H&E)-stained tumor tissue at × 400 magnification revealing a nested growth pattern and an exceedingly well-vascularized stroma. C Chromogranin A immunostaining at × 400 magnification. Note the diffusely positive cytosolic staining. D Sustentacular cells visualized using an S100 staining. E The Ki-67 proliferation index can be used to assess the proliferative activity, and is also a key part of certain algorithms to assess the metastatic potential. F Positive SDHB immunohistochemistry argues against underlying SDHB, C, and D gene mutations, thereby indicating a lower risk of disseminated disease. G Core needle biopsy of a liver metastasis in a patient previously resected for a pheochromocytoma 2 years earlier, with metastatic tumor cells recognizable through their basophilic cytoplasm. These tumor cells were positive for neuroendocrine markers (not shown). Upper left portion depicts hepatocytes. H GATA3 immunohistochemistry displaying nuclear positivity. I Complete loss of sustentacular cells was noted, as evident by an S100 immunostaining. This phenomenon is often reported in metastatic cases

Underlying Genetic Aberrancies: with Focus on Metastatic PPGL

The genetics underlying the development of PPGLs is truly multifaceted. Following the identification of the von Hippel Lindau (VHL), Neurofibromatosis type (NF1) and Rearranged during transfection (RET) genes responsible for the VHL, NF1 and the multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (MEN2) multitumor syndromes respectively in which PPGL is a recurrent feature [22,23,24,25], the list has expanded considerably with the advent of comprehensive next-generation sequencing techniques. To date, germline alterations in more than 20 genes have been associated to the development of PPGL, and for this reason, the current WHO classification recommends genetic screening of all PPGL patients [1, 26]. From a histological point of view, the endocrine pathologist should also assess whether or not synchronous adrenomedullary hyperplasia is present when diagnosing pheochromocytoma, as this feature may be a clue to the occurrence of predisposing gene mutations [27, 28]. Germline mutations are most commonly detected in the Succinate dehydrogenase complex flavoprotein subunit B (SDHB), RET, VHL and NF1 genes, while somatic mutations are most commonly observed in Harvey rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (HRAS), NF1, Endothelial PAS domain-containing protein 1 (EPAS1) and RET [3, 29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. Comprehensive genetic reviews regarding these genes and their associated modus operandi in terms of influencing PPGL development have been published elsewhere [2, 3, 5].

From a pan-genomic perspective, PPGLs cluster in four main transcriptome groups; the pseudohypoxia cluster, the kinase cluster, the Wingless type (Wnt) cluster and the cortical admixture cluster [29]. The proportion of cases with either adrenal or extra-adrenal localization, the most commonly observed gene mutations, the effects on global methylation levels and risk of metastatic disease for each cluster are illustrated in Fig. 2. Tumors adhering to the kinase cluster (approximately 50% of all PPGLs) are often pheochromocytomas with low metastatic potential, and this cluster contains tumors with either germline or somatic mutations in NF1, RET, Myc-associated factor X (MAX), Transmembrane Protein 127 (TMEM127), Kinesin Family Member 1B (KIF1B-β), and HRAS [29, 38, 41,42,43,44]. The pseudohypoxia cluster contains the highest proportion of metastatic PPGLs, and hence, this group of tumors deserve some increased attention [29, 41, 45]. Patients developing tumors that adhere to this cluster are usually young, which is due to an overall high frequency of constitutional mutations in susceptibility genes associated to PPGL development [5]. Interestingly, PPGLs within this cluster can be sub-stratified depending on whether or not gene mutations encoding enzymes responsible for propelling the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle are present (Fig. 3, Fig. 4). TCA cycle aberrant PPGLs in general exhibit the highest risk of metastatic dissemination, which is due to the fact that the accumulation of onco-metabolites will inhibit the cellular effects of dioxygenases, a group of enzymes that catalyze the oxidation of various substrates via the conversion of α-ketoglutarate to succinate (Fig. 5) [46,47,48,49,50]. One important group of inhibited enzymes are the Ten-eleven translocation (TET) proteins responsible for genomic demethylation [49, 51, 52]. When TET enzymes are inhibited, the genome is more prone to hypermethylation of various regulatory regions, of which some have implication for the regulation of tumor development and metastatic spread (Fig. 5) [51,52,53,54]. On the other hand, pseudo-hypoxia-driven PPGLs without TCA cycle mutations are generally driven by mutations in the signaling networks that regulate hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-mediated transcription of target gene programs (Fig. 6). These events include inactivating mutations of the VHL, Egl-9 Family Hypoxia Inducible Factor 2 (EGLN2; encoding prolyl hydroxylase 1, PHD1) and EGLN1 (encoding PHD2) genes, as well as activating EPAS1/HIF2-α mutations [40, 55,56,57]. The net result is halted degradation of HIF, leading to increased HIF signaling and promotion of angiogenesis and proliferation [57, 58]. However, while TCA cycle aberrant and TCA cycle non-aberrant PPGLs share dysregulation of HIF signaling, the latter group lacks the epigenetic dysregulation caused by TET enzyme inhibition. Given these molecular differences, TCA cycle–driven tumors are even more prone to metastatic spread than other PPGLs within the pseudo-hypoxia cluster, and there is probably a need to distinguish TCA cycle aberrant from TCA cycle non-aberrant PPGLs in terms of risk stratification [5, 59]. This is furthermore mirrored by syndromic manifestations, in which SDHx mutated PPGLs display a significant increased risk of disseminated disease, while VHL associated tumors rarely exhibit metastatic potential—although adhering to the same transcriptional cluster [5].

Pan-genomic classification of PPGLs. By in-depth transcriptome profiling, PPGLs generally adhere to one out of four principal expressional clusters, the Wnt pathway cluster, the kinase-associated cluster, the pseudohypoxia-associated cluster, and the cortical admixture cluster. The Wnt cluster is enriched for pheochromocytomas with somatic MAML3 gene fusions as well as CSDE1 gene mutations, and these tumors have an increased risk of metastasizing compared to kinase associated and cortical admixture cluster lesions. The kinase associated cluster is built-up primarily of pheochromocytomas with low metastatic potential. Tumors in this cluster exhibit mutations in kinase-associated pathways, and genes include NF1, RET, HRAS, MAX, TMEM127, and KIF1B. The pseudohypoxia cluster includes pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas with tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle mutations (SDHx gene family, multiple other TCA cycle related enzymes) or mutations in hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-associated signaling networks (VHL, EPAS1/HIF2-α, PHD1/EGLN2, and PHD2/EGLN1). This cluster contains a subgroup of cases (mostly TCA cycle aberrant) with global hypermethylation, which is a feature generally associated to metastatic disease and worse clinical outcomes. The fourth group (cortical admixture) is represented by pheochromocytomas with kinase-associated mutations and low risk of metastatic disease. In all, 24.3% of patients with PPGLs adhering to the pseudo-hypoxia cluster exhibit metastatic disease, compared to 11.4% of patients with Wnt cluster PPGLs and 4.1% of patients with PPGLs associated to the kinase cluster [5]. In contrast, patients with PPGLs associated to the cortical admixture cluster almost always demonstrate a benign clinical course [29]

Pseudohypoxia-driven PPGLs. The pseudo-hypoxia cluster of PPGL is traditionally associated to worse clinical outcome, but a closer look at the sub-stratification of this cluster reveals an association between mutations in genes implicated in the regulation of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and increased metastatic potential, as opposed to TCA cycle non-aberrant PPGLs within the same cluster. While both subgroups activate the HIF signaling pathway, TCA cycle mutated tumors also exhibit epigenetic dysregulation as a consequence of the accumulation of onco-metabolites (fumarate, succinate, and α-ketoglutarate (α-KG) derivatives. The risk of metastatic events among patients with pseudohypoxia-driven PPGLs is much higher in TCA cycle aberrant cases (40.5% of patients) than in TCA cycle non-aberrant cases (11.2% of patients) [5]

Tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle dysregulation in PPGLs. In normal circumstances, the TCA cycle is an orchestrated chain of events propelled by a number of key enzymes, in which energy is extracted through the oxidation of acetyl-CoA. Each step of the TCA cycle is tightly regulated by enzymes, of which the majority can be inactivated through gene mutations (red stars) in PPGLs. These events are thought to cause an accumulation of key metabolites, in turn affecting other cellular processes reviewed in upcoming figures. Mutations in isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH), the α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase subunit dihydrolipoamide s-succinyltransferase (DLST), succinate dehydrogenase complex flavoprotein subunits A, B, C, D and succinate dehydrogenase complex assembly factor 2 (SDHAF2), fumarate hydratase (FH) and malate dehydrogenase (MDH) have all been reported on either the somatic or germline level in PPGL. Moreover, gene mutations involving transporter molecules responsible for the shuttling of malate and α-ketoglutarate (SLC25A11), as well as activating mutations (green star) in genes catalyzing the conversion of glutamate to α-ketoglutarate (GOT2), are also reported

Cellular consequences of an aberrant tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle in PPGLs. In the normal cell state, the TCA cycle operates at normal capacity, generating ATP and keeping extra-mitochondrial levels of onco-metabolites (succinate, fumarate, and α-ketoglutarate (α-KG)) derivative levels low. Thus, the diverse group of α-KG dependent dioxygenase enzymes (including PHD enzymes targeting the HIF oncoprotein for degradation as well as TET proteins responsible for de-methylating the genome) is functional. Upon aberrant TCA cycle regulation (via mutations in genes encoding enzymes catalyzing key steps of the TCA cycle), accumulation of extra-mitochondrial succinate, fumarate and α-KG metabolites will inhibit dioxygenase function, leading to impaired PHD and TET enzyme activity—thereby promoting HIF pathway activation and genomic hypermethylation

Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) pathway regulation in normal states and in PPGL development. In the normal state (left), HIF signaling is impaired by the PHD enzyme class mediated hydroxylation of HIF-α, in turn marking the latter protein for proteolysis via the actions of the von Hippel Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor protein. If oxygen levels are reduced, HIF-α escapes hydroxylation and degradation, and initiates intra-nuclear target transcriptome programs, including those associated to angiogenesis. In PPGLs (right), activating EPAS1 (encoding HIF-2α) mutations (green star), inactivating VHL, PHD1/EGLN2 and PHD2/EGLN1 mutations (red stars) as well as aberrant TCA cycle regulation leading to inhibition of PHDs are main genetic events activating the HIF signaling cascade—even at normal oxygen levels

The Wnt cluster contains mostly pheochromocytomas with somatic fusions involving the Mastermind Like Transcriptional Coactivator 3 (MAML3) gene as well as Cold Shock Domain Containing E1 (CDSE1) mutations [29]. The MAML3 protein acts as a transcriptional coactivator of NOTCH pathway associated genes, and MAML3 fusions and MAML3 overexpression are recurrent features in various tumor types [60,61,62]. In PPGL, the fusion partners Upstream Binding Transcription Factor (UBTF) and Transcription Factor 4 (TCF4) promoter regions, stimulate constitutive overexpression of MAML3 [29]. The CDSE1 gene encodes an RNA binding protein involved in translational programming and RNA turnover [63, 64]. In PPGL, CDSE1 mutations are found on the somatic level and are expected to exhibit loss-of-function properties [29]. From a clinical standpoint, this Wnt expressional cluster also contains PPGLs at risk of metastatic dissemination, probably arguing for tumor DNA screening of MAML3 gene fusions and CDSE1 mutations as an efficient way to identify additional high-risk cases that will be negative for other TCA cycle and pseudo-hypoxia-related aberrancies [5, 29].

Finally, the cortical admixture cluster is characterized by pheochromocytomas with NF1 somatic mutations as well as MEN2-related tumors with RET germline mutations. This cluster is enriched for adrenal cortical markers such as CYP11B1 and CYP21A2, which is probably due to the interspersion of adrenal cortical cells [29]. PPGL within this cluster exhibit a very low risk of metastatic spread.

Pinpointing Metastatic Potential using Histological Algorithms—Is it Possible?

Although not fully recommended by the current WHO classification, histological scoring systems are frequently used in the scientific literature when assessing the metastatic potential of PPGLs [1]. Even though the amount of verifying studies still is limited and the reproducibility debated, the intention of these algorithms is to provide the endocrine pathologist with schemes that might facilitate the identification of cases at risk of future dissemination. However, the limitations of these risk assessment models are mandatory to take into consideration when interpreting the outcome of each individual tumor.

The Pheochromocytoma of the Adrenal gland Scaled Score (PASS) was developed in 2002 as a method to identify pheochromocytomas with potential for aggressive behavior [65]. Dr. Thompson compared 50 “histologically malignant” and 50 “histologically benign” pheochromocytomas and identified key microscopic features that differed between groups. The algorithm is strictly histology-based and incorporates 12 different parameters that yield a score ranging from 0 to 20 points. One point each is given for the presence of nuclear hyperchromasia, profound nuclear pleomorphism, capsular invasion, or vascular invasion, whereas two points per parameter is given for large nests/compact growth, tumor necrosis, high cellularity, cellular monotony, tumor cell spindling, > 3 mitoses per 10 high power fields, atypical mitoses, and extension into surrounding adipose tisse (Fig. 7). In the original cohort, a PASS score of 4 points or more indicated an increased risk of future aggressive behavior [65]. The scheme has been confirmed in several independent series [66,67,68,69,70], but not in other [71, 72]. Moreover, in terms of intra-observer variability, the PASS algorithm has been proven subpar—with different pathologists reaching different scores for a considerable proportion of cases [72, 73].

Schematic overview of the Pheochromocytoma of the Adrenal gland Scaled Score (PASS) and the Grading System for Adrenal Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma (GAPP) algorithms. Including parameters are listed, as well as the individual points given for each fulfilled criteria. Bottom row depicts the high negative predictive value of both algorithms as suggested by a recent meta-analysis, indicating that low PASS/GAPP scores are strongly associated to benign clinical courses, while elevated PASS/GAPP scores are recurrently reported in metastatic-free PPGLs—thereby limiting the value of these algorithms as “rule-in” tests. P point, E epinephrine, NP non-producing, NE norepinephrine

The PASS parameters listed above are classical attributes normally associated to malignant phenotypes in various human tumors. In this aspect, the PASS algorithm could be considered a “histological shotgun,” with a wide spread of microscopic criteria that will pinpoint cases at risk of spread—but also with an increased risk of false positives. Indeed, a recent meta-analysis of > 800 pheochromocytomas with retrievable PASS scores and follow-up data [74] identified this algorithm as highly sensitive for the detection of metastatic cases with an ensuing high negative predictive value. However, the specificity and corresponding positive predictive value were both low (Fig. 7). Therefore, the PASS algorithm could be viewed as a model to rule out metastatic potential (if the score is low), rather than to actually pinpoint cases that will behave malignant. Strikingly, the number of clinically benign pheochromocytomas with elevated PASS scores in the literature surpass the number of reported metastatic cases with similarly high PASS scores [74]. An example of the reduced specificity of the PASS algorithm is provided in Fig. 8, in which a resected pheochromocytoma with a recurrence-free follow-up time of 20 years displayed a pathological PASS score of 5, including vascular invasion, periadrenal invasion, capsular invasion, and nuclear pleomorphism. This serves as an illustration as to how PASS incorrectly may identify pheochromocytomas with little or no metastatic potential as potentially worrisome specimen in need of intensified follow-up. Moreover, specific genotype–phenotype observations of importance for MEN2A-associated PPGL have also been reported, as these tumors often present with large, irregular nests, focal tumor cell spindling, and an elevated Ki-67 index (Fig. 8) [75]. As of this, PPGL patients with germline RET mutations may exhibit alarming histological features, although these patients very rarely present with metastatic disease in the clinical setting. Therefore, it is imperative to take into consideration the medical history of each patient when conducting histological assessment of PPGLs—and the abovementioned example also serves to illustrate the importance of molecular genetics in complementing the pathology report in terms of accurate prognostication.

Overstating the risk of aggressive behavior in PPGLs using current risk stratification algorithms. All images are routine hematoxylin–eosin stains. Images A-D depict a resected pheochromocytoma with a recurrence-free follow-up time of 20 years. A Pleomorphic features. B Capsular invasion. C Comedo-type necrosis. D Vascular invasion. The Pheochromocytoma of the Adrenal gland Scaled Score (PASS) was elevated (5 points); thus, the algorithm falsely identified metastatic potential in this instance. E, F A large proportion of PPGLs arising in MEN2A patients display large, irregular nests (E) and focal tumor cell spindling (F). Large nests is a parameter listed in both the PASS and the Grading System for Adrenal Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma (GAPP) algorithms, and tumor cell spindling is an additional PASS related parameter. From a clinical standpoint, pheochromocytomas in MEN2 patients very rarely metastasize

The Grading System for Adrenal Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma (GAPP) score was published in 2014 by Dr Kimura and co-workers, in which the authors studied 163 PPGLs, including 40 metastatic cases [76]. Unlike the PASS algorithm, the GAPP study incorporated both pheochromocytomas as well as abdominal paragangliomas, and aimed to highlight contributing factors indicating metastatic potential for this collective tumor group. Building on the PASS algorithm, the GAPP scoring system combines histological findings, immunohistochemistry and clinical information. More specifically, the GAPP score is retrieved by evaluating histological parameters (growth pattern, cellularity, presence of comedo-type necrosis, capsular and vascular invasion), the Ki-67 labelling index as well as the biochemical profile (catecholamine type) (Fig. 7). Noradrenergic PPGLs express low levels of the phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PNMT) enzyme that converts norepinephrine to epinephrine, and reduced PNMT expression is in turn highly related to the pseudo-hypoxia signaling pathway [5, 77]. Therefore, norepinephrine secreting PPGLs are more likely to adhere to transcriptional clusters associated to metastatic behavior, which is also reflected in the GAPP score. The PPGLs are given a score ranging from 0 to 10 points, and subsequently graded as either well differentiated (WD, 0–2 points), moderately differentiated (MD, 3–6 points), or poorly differentiated (PD, 7–10 points). In this study, WD-PPGLs were all metastatic-free, while the metastatic proportion of cases was higher (and the disease-specific survival lower) in the MD and PD groups [76]. Moreover, time to a metastatic event decreased with increased GAPP scores. The GAPP scoring algorithm has only been reproduced in few independent studies and is still a fairly young study in need of additional verification [72, 74, 78]. In the meta-analysis discussed above, the GAPP system exhibited a well-trusted “rule-out” function based on the excellent negative predictive value, similarly to what was shown for PASS (Fig. 7) [74]. However, the rather frequent finding of clinically benign PPGLs with scores ≥ 3 points makes the positive predictive value rather low, and hence puts a strain to the ability to truly identify cases at risk of metastatic spread.

Early Immunohistochemical Analyses

Given the association between increased mitotic activity and risk of metastatic spread, researches early on turned to the Ki-67 proliferation marker in order to highlight cases at risk of dissemination. Studies seem to agree that clinically aggressive PPGLs are associated to higher Ki-67 indices, although overlaps exist [79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87]. Thus, there seem to be a large amount of scientific data that justified the inclusion of Ki-67 as one key parameter in the GAPP algorithm [76]. As Ki-67 is a part of the antibody lineup in most pathology laboratories and a stain that endocrine pathologists are acquainted to in terms of interpretation, this marker is thus a useful and potentially reproducible tool in the assessment of metastatic potential of PPGLs. Other early observations include the visualization of reduced amounts of sustentacular cells in metastatic PPGLs as visualized via S100 immunohistochemistry [87,88,89,90,91,92]. However, the S100 staining patterns might be heterogeneous and thereby hard to interpret, especially in larger tumors [89].

Immunohistochemistry as Molecular Triaging

The advent of modern next-generation analyses have revolutionized the ability to classify PPGLs, not only in terms of transcriptome clustering but also as a way to detect germline alterations in patients in need of genetic counselling and to pinpoint high-risk mutations in TCA cycle/pseudo-hypoxia-related PPGLs indicating higher risk of metastatic events. Even so, immunohistochemistry is still considered an efficient, cheap, and reproducible method to pinpoint cases in need of intensified molecular studies, as well as to evaluate the functional consequences of some genetic variants of uncertain significance detected through clinical genetics workup [93]. In terms of prognostication and clinical significance, SDHB immunohistochemistry is probably the most well-established marker to date. Following the detection of absent SDHB expression in hereditary PPGLs in patients with germline SDHB or SDHD mutations, several independent groups have verified the value of SDHB immunohistochemistry to pinpoint SDHx gene mutations occurring either on the somatic or germline level in PPGL [94,95,96,97]. The reason behind the ability of SDHB staining to pinpoint cases with either SDHB, C, or D subunit mutations stems from the fact that the succinate dehydrogenase enzyme complex is anchored to the mitochondrial inner membrane via the C and D subunits. Thus, mutational inactivation of SDHB, C, or D will cause a disruption of the entire complex, leading to absent SDHB immunoreactivity (Fig. 9) [98]. The scoring and interpretation of SDHB immunohistochemistry has been proved highly reproducible between pathologists and also a reliable tool in terms of detecting underlying SDHx gene mutations [99]. It should however be stressed that subsets of SHDB-immunodeficient PPGLs could display wild-type SDHx gene sequences, but instead exhibit SDHC promoter hypermethylation, alternatively VHL or NF1 gene mutations [99, 100]. In contrast, SDHA mutated PPGLs lose both SDHA and B immunoreactivity, and therefore, SDHA immunohistochemistry could complement the screening panel to detect rare PPGLs with SDHA mutations [99, 101]. SDHD immunostaining has also been assessed in PPGLs, in which positive immunoreactivity was observed in SDHx gene mutated cases—while wild-type cases stained negative. The reason for this paradoxal and inverted finding could be the potential de-masking of the SDHD epitope upon mutation-mediated disruption of the SDH complex [102]. Moreover, immunohistochemistry targeting fumarate hydratase (FH) has been proven as an efficient method to pinpoint rare FH gene germline mutations in PPGL [103], in turn coupled to the hereditary leiomatosis and renal cell carcinoma (HLRCC) syndrome [104].

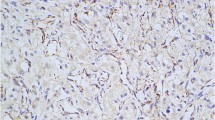

Urinary bladder paraganglioma with an underlying SDHB mutation detected through immunohistochemistry. A Routine hematoxylin–eosin stain of a urinary bladder paraganglioma arising in a young female patient. B SDHB immunohistochemistry revealing absent tumor staining, while adjacent sustentacular cells and stromal components were positive. This staining pattern is highly indicative of an underlying SDHx gene mutation. C The SDHA immunostaining was positive, as indicated by a granular, cytoplasmic signal. D Regional lymph node exhibiting synchronous metastatic deposits. Clinical genetics counseling was initiated, and the patient was found to harbor a germline SDHB mutation

Apart from the abovementioned markers used to pinpoint PPGLs associated to an aberrant TCA cycle, two markers have shown promise to identify pseudo-hypoxia and kinase cluster associated tumors, respectively, namely carbonic anhydrase IX (CAIX) and MAX. CAIX is frequently found up-regulated in PPGL with underlying VHL gene mutations, and the identification of strong immunoreactivity in a PPGL might therefore be a way to identify VHL driven tumors with a lower (but not unneglectable) risk of aggressive behavior than TCA cycle aberrant PPGLs [105]. Similarly, rare cases of MAX mutated or gene rearranged PPGLs usually exhibit loss of MAX protein expression—adding yet another potential tool to the diagnostic workup of these lesions [27, 106]. In contrast, NF1 and RET immunohistochemistry cannot yet be recommended as a way to identify underlying NF1 and RET gene mutations, as both sensitivity and specificity have been found reduced in previous studies [107, 108].

Besides immunohistochemical analyses aiding in the context of underlying mutations, an additional marker of prognostic significance include chromogranin B (CHGB), which was the top downregulated gene in an expressional study when stratifying for metastatic PPGLs [70]. The finding was reproduced using immunohistochemistry, with negative or low levels of CHGB immunoreactivity in metastatic PPGLs. Moreover, low preoperative plasma levels of CHGB were associated to higher PASS scores in the resected tumor. Thus, CHGB could possibly act as a preoperative marker of PPGLs with histological worrisome features.

Overall, a combined effort of histology and molecular immunohistochemistry is probably needed for the endocrine pathologist in order to better estimate the metastatic potential of each individual PPGL, including diagnostic and prognostic immunohistochemistry (Fig. 10). Moreover, the potential benefit of risk stratification algorithms has to be weighed against the risk of false positives and limited reproducibility, but could potentially be of value to identify cases with little risk of future dissemination.

Molecular immunohistochemistry of PPGLs. The endocrine pathologist needs to verify the diagnosis through a concerted action of histology and immunohistochemical markers that pinpoint the chromaffin cell origin. In terms of immunohistochemistry, a succinate dehydrogenase complex flavoprotein subunit B (SDHB) staining could pinpoint cases with underlying SHDx gene mutations and an increased risk of disseminated disease. Aberrant carbonic anhydrase IX (CAIX) and MYC associated factor X (MAX) immunostainings might indicate mutations in the von Hippel Lindau (VHL) or MAX genes, respectively, while the proliferation marker Ki-67 could be used to prognosticate the tumors further

Next-Generation Multi-OMICs Characterization—the Necessary Step

Recent next-generation sequencing studies of PPGLs have increased our understanding of molecular aberrancies that associate to metastatic potential. As previously discussed, gene fusions involving MAML3 and CDSE1 mutations are overrepresented in PPGL associated to the Wnt transcriptome cluster, and these tumors have a significantly higher metastatic rate than PPGL associated to the kinase cluster [5, 29]. These aberrancies are somatic and will thus not be identified during a clinical routine screening of germline DNA. Moreover, metastatic PPGLs also harbor somatic gene alterations of potential value for further investigations, such as mutations in transport and cell adhesion genes [109], recurrent Transcriptional regulator ATRX (ATRX) mutations [29, 110] as well as upregulated Telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) gene expression and TERT gene rearrangements [111, 112]. TERT gene aberrancies are common in various cancers and usually confer an increased TERT mRNA gene output, which is thought to confer immortalization through the elongation of telomeric DNA for these tumor types [85, 112, 113]. ATRX encodes a chromatin remodeling protein, and mutations in this gene were intimately coupled to an alternative lengthening of telomeres, furthermore suggesting that the regulation of telomeric regions is crucial for metastatic PPGLs [29]. To add to the association between epigenetic regulators and metastatic potential, somatic mutations in SET domain containing 2 histone lysine methyltransferase (SETD2) have also been found overrepresented in PPGLs with disseminated disease [29]. SETD2 is a regulator of various cellular processes such as RNA splicing, DNA repair, DNA methylation and histone modification, and is considered a tumor suppressor in unrelated tumor types [114, 115]. In contrast, mutations in other components of the epigenetic machinery that governs chromatin remodeling are mostly found in metastatic-free PPGLs [31, 116]. Overall, screening for somatic gene aberrancies could complement routine histopathology and molecular immunohistochemical analyses in the hunt for PPGLs with metastatic potential, leading to more efficient pinpointing of high-risk cases.

In terms of epigenetic modifications, we know that especially TCA cycle aberrant PPGLs display unique methylation profiles on both global and gene-specific levels [52, 117, 118]. Although no clear-cut methylation panel for clinical usage in terms of prognostication exists, the association between hypermethylation, TCA cycle defects and metastatic PPGLs could have clinical implications in terms of treatment. For example, as O(6)-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) constitutes an epigenetically silenced gene in SDHx mutated PPGLs, this could probably explain the partial effect of temozolomide in these cases [119].

Discussion

PPGLs are enigmatic lesions that pose a serious challenge even to tertiary center experts, not only in terms of clinical handling, but also (and perhaps; particularly) in terms of prognostication of each individual patient. The multifaceted genetic background and the complex association between histological hallmarks of malignancy and clinical evidence of metastatic spread requires a pathologist that can juggle with radiological, biochemical, genetic and histological parameters in order to prognosticate these lesions. Most importantly, an awareness of the limitations of each of these factors to pinpoint risk of disease dissemination is crucial, especially as overconfidence in any parameter might falsely indicate a placid PPGL as potentially aggressive. Thus, a modern endocrine pathologist needs to be updated not only on histological algorithms but also on the ever-dynamic genetic landscape and recent developments within the field of molecular testing. Moreover, additional coordinated multicenter research efforts will most likely be needed to fully dissect the molecular aberrancies that govern the malignant potential of PPGLs.

References

Lloyd RV, Osamura RY, Klöppel G, Rosai J, International Agency for Research on Cancer (2017) WHO classification of tumours of endocrine organs, 4th edition. International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon

Antonio K, Valdez MMN, Mercado-Asis L, Taïeb D, Pacak K (2020) Pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma: recent updates in genetics, biochemistry, immunohistochemistry, metabolomics, imaging and therapeutic options. Gland Surg 9:105–123. https://doi.org/10.21037/gs.2019.10.25

Buffet A, Burnichon N, Favier J, Gimenez-Roqueplo A-P (2020) An overview of 20 years of genetic studies in pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 34:101416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beem.2020.101416

Favier J, Amar L, Gimenez-Roqueplo A-P (2015) Paraganglioma and phaeochromocytoma: from genetics to personalized medicine. Nat Rev Endocrinol 11:101–111. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2014.188

Crona J, Lamarca A, Ghosal S, Welin S, Skogseid B, Pacak K (2019) Genotype-phenotype correlations in pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: a systematic review and individual patient meta-analysis. Endocr Relat Cancer 26:539–550. https://doi.org/10.1530/ERC-19-0024

Ebbehoj A, Stochholm K, Jacobsen SF, Trolle C, Jepsen P, Robaczyk MG, Rasmussen ÅK, Feldt-Rasmussen U, Thomsen RW, Søndergaard E, Poulsen PL (2021) Incidence and Clinical Presentation of Pheochromocytoma and Sympathetic Paraganglioma: A Population-based Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgaa965

Granberg D, Juhlin CC, Falhammar H (2021) Metastatic Pheochromocytomas and Abdominal Paragangliomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgaa982

Falhammar H, Kjellman M, Calissendorff J (2018) Initial clinical presentation and spectrum of pheochromocytoma: a study of 94 cases from a single center. Endocr Connect 7:186–192. https://doi.org/10.1530/EC-17-0321

Čtvrtlík F, Koranda P, Schovánek J, Škarda J, Hartmann I, Tüdös Z (2018) Current diagnostic imaging of pheochromocytomas and implications for therapeutic strategy. Exp Ther Med 15:3151–3160. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2018.5871

Gimenez-Roqueplo A-P, Caumont-Prim A, Houzard C, Hignette C, Hernigou A, Halimi P, Niccoli P, Leboulleux S, Amar L, Borson-Chazot F, Cardot-Bauters C, Delemer B, Chabolle F, Coupier I, Libé R, Peitzsch M, Peyrard S, Tenenbaum F, Plouin P-F, Chatellier G, Rohmer V (2013) Imaging work-up for screening of paraganglioma and pheochromocytoma in SDHx mutation carriers: a multicenter prospective study from the PGL.EVA Investigators. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 98:E162-173. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2012-2975

van Berkel A, Lenders JWM, Timmers HJLM (2014) Diagnosis of endocrine disease: Biochemical diagnosis of phaeochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Eur J Endocrinol 170:R109-119. https://doi.org/10.1530/EJE-13-0882

PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board (2002) Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma Treatment (PDQ®): Health Professional Version. In: PDQ Cancer Information Summaries. National Cancer Institute (US), Bethesda (MD)

Quayle FJ, Spitler JA, Pierce RA, Lairmore TC, Moley JF, Brunt LM (2007) Needle biopsy of incidentally discovered adrenal masses is rarely informative and potentially hazardous. Surgery 142:497–502; discussion 502–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2007.07.013

Mamilla D, Manukyan I, Fetsch PA, Pacak K, Miettinen M (2020) Immunohistochemical distinction of paragangliomas from epithelial neuroendocrine tumors-gangliocytic duodenal and cauda equina paragangliomas align with epithelial neuroendocrine tumors. Hum Pathol 103:72–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2020.07.010

Kimura N (2021) Dopamine β-hydroxylase: An Essential and Optimal Immunohistochemical Marker for Pheochromocytoma and Sympathetic Paraganglioma. Endocr Pathol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12022-020-09655-w

Juhlin CC, Zedenius J, Höög A (2020) Clinical Routine Application of the Second-generation Neuroendocrine Markers ISL1, INSM1, and Secretagogin in Neuroendocrine Neoplasia: Staining Outcomes and Potential Clues for Determining Tumor Origin. Endocr Pathol 31:401–410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12022-020-09645-y

Perrino CM, Ho A, Dall CP, Zynger DL (2017) Utility of GATA3 in the differential diagnosis of pheochromocytoma. Histopathology 71:475–479. https://doi.org/10.1111/his.13229

Asa SL, Ezzat S, Mete O (2018) The Diagnosis and Clinical Significance of Paragangliomas in Unusual Locations J Clin Med 7 https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/7/9/280

Thompson LDR, Gill AJ, Asa SL, Clifton-Bligh RJ, de Krijger RR, Kimura N, Komminoth P, Lack EE, Lenders JWM, Lloyd RV, Papathomas TG, Sadow PM, Tischler AS (2020) Data set for the reporting of pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: explanations and recommendations of the guidelines from the International Collaboration on Cancer Reporting. Hum Pathol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2020.04.012

Amin MB, American Joint Committee on Cancer, American Cancer Society (2017) AJCC cancer staging manual, Eight edition / editor-in-chief, Mahul B. Amin, MD, FCAP ; editors, Stephen B. Edge, MD, FACS [and 16 others] ; Donna M. Gress, RHIT, CTR-Technical editor ; Laura R. Meyer, CAPM-Managing editor. American Joint Committee on Cancer, Springer, Chicago IL

Stenman A, Zedenius J, Juhlin CC (2019) Retrospective application of the pathologic tumor-node-metastasis classification system for pheochromocytoma and abdominal paraganglioma in a well characterized cohort with long-term follow-up. Surgery 166:901–906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2019.04.030

Seizinger BR, Rouleau GA, Ozelius LJ, Lane AH, Farmer GE, Lamiell JM, Haines J, Yuen JW, Collins D, Majoor-Krakauer D (1988) Von Hippel-Lindau disease maps to the region of chromosome 3 associated with renal cell carcinoma. Nature 332:268–269. https://doi.org/10.1038/332268a0

Seizinger BR, Rouleau GA, Lane AH, Farmer G, Ozelius LJ, Haines JL, Parry DM, Korf BR, Pericak-Vance MA, Faryniarz AG (1987) Linkage analysis in von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis (NF1) with DNA markers for chromosome 17. Genomics 1:346–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/0888-7543(87)90035-8

Lairmore TC, Dou S, Howe JR, Chi D, Carlson K, Veile R, Mishra SK, Wells SA, Donis-Keller H (1993) A 1.5-megabase yeast artificial chromosome contig from human chromosome 10q11.2 connecting three genetic loci (RET, D10S94, and D10S102) closely linked to the MEN2A locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90:492–496. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.90.2.492

Mulligan LM, Kwok JB, Healey CS, Elsdon MJ, Eng C, Gardner E, Love DR, Mole SE, Moore JK, Papi L (1993) Germ-line mutations of the RET proto-oncogene in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A. Nature 363:458–460. https://doi.org/10.1038/363458a0

Currás-Freixes M, Inglada-Pérez L, Mancikova V, Montero-Conde C, Letón R, Comino-Méndez I, Apellániz-Ruiz M, Sánchez-Barroso L, Aguirre Sánchez-Covisa M, Alcázar V, Aller J, Álvarez-Escolá C, Andía-Melero VM, Azriel-Mira S, Calatayud-Gutiérrez M, Díaz JÁ, Díez-Hernández A, Lamas-Oliveira C, Marazuela M, Matias-Guiu X, Meoro-Avilés A, Patiño-García A, Pedrinaci S, Riesco-Eizaguirre G, Sábado-Álvarez C, Sáez-Villaverde R, Sainz de Los Terreros A, Sanz Guadarrama Ó, Sastre-Marcos J, Scolá-Yurrita B, Segura-Huerta Á, Serrano-Corredor M de la S, Villar-Vicente MR, Rodríguez-Antona C, Korpershoek E, Cascón A, Robledo M (2015) Recommendations for somatic and germline genetic testing of single pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma based on findings from a series of 329 patients. J Med Genet 52:647–656. https://doi.org/10.1136/jmedgenet-2015-103218

Romanet P, Guerin C, Pedini P, Essamet W, Castinetti F, Sebag F, Roche P, Cascon A, Tischler AS, Pacak K, Barlier A, Taïeb D (2017) Pathological and Genetic Characterization of Bilateral Adrenomedullary Hyperplasia in a Patient with Germline MAX Mutation. Endocr Pathol 28:302–307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12022-016-9460-5

Falhammar H, Stenman A, Calissendorff J, Juhlin CC (2019) Presentation, Treatment, Histology, and Outcomes in Adrenal Medullary Hyperplasia Compared With Pheochromocytoma. J Endocr Soc 3:1518–1530. https://doi.org/10.1210/js.2019-00200

Fishbein L, Leshchiner I, Walter V, Danilova L, Robertson AG, Johnson AR, Lichtenberg TM, Murray BA, Ghayee HK, Else T, Ling S, Jefferys SR, de Cubas AA, Wenz B, Korpershoek E, Amelio AL, Makowski L, Rathmell WK, Gimenez-Roqueplo A-P, Giordano TJ, Asa SL, Tischler AS, Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, Pacak K, Nathanson KL, Wilkerson MD (2017) Comprehensive Molecular Characterization of Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma. Cancer Cell 31:181–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2017.01.001

Astuti D, Latif F, Dallol A, Dahia PL, Douglas F, George E, Sköldberg F, Husebye ES, Eng C, Maher ER (2001) Gene mutations in the succinate dehydrogenase subunit SDHB cause susceptibility to familial pheochromocytoma and to familial paraganglioma. Am J Hum Genet 69:49–54. https://doi.org/10.1086/321282

Juhlin CC, Stenman A, Haglund F, Clark VE, Brown TC, Baranoski J, Bilguvar K, Goh G, Welander J, Svahn F, Rubinstein JC, Caramuta S, Yasuno K, Günel M, Bäckdahl M, Gimm O, Söderkvist P, Prasad ML, Korah R, Lifton RP, Carling T (2015) Whole-exome sequencing defines the mutational landscape of pheochromocytoma and identifies KMT2D as a recurrently mutated gene. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 54:542–554. https://doi.org/10.1002/gcc.22267

Welander J, Andreasson A, Juhlin CC, Wiseman RW, Bäckdahl M, Höög A, Larsson C, Gimm O, Söderkvist P (2014) Rare germline mutations identified by targeted next-generation sequencing of susceptibility genes in pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 99:E1352-1360. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2013-4375

J Jiang J Zhang Y Pang N Bechmann M Li M Monteagudo B Calsina A-P Gimenez-Roqueplo S Nölting F Beuschlein M Fassnacht T Deutschbein HJLM Timmers T Åkerström J Crona M Quinkler SMJ Fliedner Y Liu J Guo X Li W Guo Y Hou C Wang L Zhang Q Xiao L Liu X Gao N Burnichon M Robledo G Eisenhofer 2020 Sino-European Differences in the Genetic Landscape and Clinical Presentation of Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma J Clin Endocrinol Metab 105. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgaa502

Buffet A, Burnichon N, Amar L, Gimenez-Roqueplo A-P (2018) Pheochromocytoma: When to search a germline defect? Presse Med 47:e109–e118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lpm.2018.07.003

NGS in PPGL (NGSnPPGL) Study Group, Toledo RA, Burnichon N, Cascon A, Benn DE, Bayley J-P, Welander J, Tops CM, Firth H, Dwight T, Ercolino T, Mannelli M, Opocher G, Clifton-Bligh R, Gimm O, Maher ER, Robledo M, Gimenez-Roqueplo A-P, Dahia PLM (2017) Consensus Statement on next-generation-sequencing-based diagnostic testing of hereditary phaeochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Nat Rev Endocrinol 13:233–247. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2016.185

Castro-Vega LJ, Letouzé E, Burnichon N, Buffet A, Disderot P-H, Khalifa E, Loriot C, Elarouci N, Morin A, Menara M, Lepoutre-Lussey C, Badoual C, Sibony M, Dousset B, Libé R, Zinzindohoue F, Plouin PF, Bertherat J, Amar L, de Reyniès A, Favier J, Gimenez-Roqueplo A-P (2015) Multi-omics analysis defines core genomic alterations in pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Nat Commun 6:6044. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7044

Burnichon N, Buffet A, Parfait B, Letouzé E, Laurendeau I, Loriot C, Pasmant E, Abermil N, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Bertherat J, Amar L, Vidaud D, Favier J, Gimenez-Roqueplo A-P (2012) Somatic NF1 inactivation is a frequent event in sporadic pheochromocytoma. Hum Mol Genet 21:5397–5405. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/dds374

Crona J, Delgado Verdugo A, Maharjan R, Stålberg P, Granberg D, Hellman P, Björklund P (2013) Somatic mutations in H-RAS in sporadic pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma identified by exome sequencing. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 98:E1266-1271. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2012-4257

L Oudijk RR Krijger de I Rapa F Beuschlein AA Cubas de AP Dei Tos WNM Dinjens E Korpershoek V Mancikova M Mannelli M Papotti S Vatrano M Robledo M Volante 2014 H-RAS mutations are restricted to sporadic pheochromocytomas lacking specific clinical or pathological features: data from a multi-institutional series J Clin Endocrinol Metab 99 E1376 1380. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2013-3879

Comino-Méndez I, de Cubas AA, Bernal C, Álvarez-Escolá C, Sánchez-Malo C, Ramírez-Tortosa CL, Pedrinaci S, Rapizzi E, Ercolino T, Bernini G, Bacca A, Letón R, Pita G, Alonso MR, Leandro-García LJ, Gómez-Graña A, Inglada-Pérez L, Mancikova V, Rodríguez-Antona C, Mannelli M, Robledo M, Cascón A (2013) Tumoral EPAS1 (HIF2A) mutations explain sporadic pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma in the absence of erythrocytosis. Hum Mol Genet 22:2169–2176. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddt069

Burnichon N, Vescovo L, Amar L, Libé R, de Reynies A, Venisse A, Jouanno E, Laurendeau I, Parfait B, Bertherat J, Plouin P-F, Jeunemaitre X, Favier J, Gimenez-Roqueplo A-P (2011) Integrative genomic analysis reveals somatic mutations in pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Hum Mol Genet 20:3974–3985. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddr324

Qin Y, Yao L, King EE, Buddavarapu K, Lenci RE, Chocron ES, Lechleiter JD, Sass M, Aronin N, Schiavi F, Boaretto F, Opocher G, Toledo RA, Toledo SPA, Stiles C, Aguiar RCT, Dahia PLM (2010) Germline mutations in TMEM127 confer susceptibility to pheochromocytoma. Nat Genet 42:229–233. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.533

Comino-Méndez I, Gracia-Aznárez FJ, Schiavi F, Landa I, Leandro-García LJ, Letón R, Honrado E, Ramos-Medina R, Caronia D, Pita G, Gómez-Graña A, de Cubas AA, Inglada-Pérez L, Maliszewska A, Taschin E, Bobisse S, Pica G, Loli P, Hernández-Lavado R, Díaz JA, Gómez-Morales M, González-Neira A, Roncador G, Rodríguez-Antona C, Benítez J, Mannelli M, Opocher G, Robledo M, Cascón A (2011) Exome sequencing identifies MAX mutations as a cause of hereditary pheochromocytoma. Nat Genet 43:663–667. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.861

Schlisio S, Kenchappa RS, Vredeveld LCW, George RE, Stewart R, Greulich H, Shahriari K, Nguyen NV, Pigny P, Dahia PL, Pomeroy SL, Maris JM, Look AT, Meyerson M, Peeper DS, Carter BD, Kaelin WG (2008) The kinesin KIF1Bbeta acts downstream from EglN3 to induce apoptosis and is a potential 1p36 tumor suppressor. Genes Dev 22:884–893. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.1648608

Span PN, Rao JU, Oude Ophuis SBJ, Lenders JWM, Sweep FCGJ, Wesseling P, Kusters B, van Nederveen FH, de Krijger RR, Hermus ARMM, Timmers HJLM (2011) Overexpression of the natural antisense hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha transcript is associated with malignant pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma. Endocr Relat Cancer 18:323–331. https://doi.org/10.1530/ERC-10-0184

Smith EH, Janknecht R, Maher LJ (2007) Succinate inhibition of alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent enzymes in a yeast model of paraganglioma. Hum Mol Genet 16:3136–3148. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddm275

Richter S, Peitzsch M, Rapizzi E, Lenders JW, Qin N, de Cubas AA, Schiavi F, Rao JU, Beuschlein F, Quinkler M, Timmers HJ, Opocher G, Mannelli M, Pacak K, Robledo M, Eisenhofer G (2014) Krebs cycle metabolite profiling for identification and stratification of pheochromocytomas/paragangliomas due to succinate dehydrogenase deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 99:3903–3911. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2014-2151

Lendvai N, Pawlosky R, Bullova P, Eisenhofer G, Patocs A, Veech RL, Pacak K (2014) Succinate-to-fumarate ratio as a new metabolic marker to detect the presence of SDHB/D-related paraganglioma: initial experimental and ex vivo findings. Endocrinology 155:27–32. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2013-1549

Xiao M, Yang H, Xu W, Ma S, Lin H, Zhu H, Liu L, Liu Y, Yang C, Xu Y, Zhao S, Ye D, Xiong Y, Guan K-L (2012) Inhibition of α-KG-dependent histone and DNA demethylases by fumarate and succinate that are accumulated in mutations of FH and SDH tumor suppressors. Genes Dev 26:1326–1338. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.191056.112

Gill AJ (2012) Succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) and mitochondrial driven neoplasia. Pathology 44:285–292 . https://doi.org/10.1097/PAT.0b013e3283539932

Morin A, Goncalves J, Moog S, Castro-Vega L-J, Job S, Buffet A, Fontenille M-J, Woszczyk J, Gimenez-Roqueplo A-P, Letouzé E, Favier J (2020) TET-Mediated Hypermethylation Primes SDH-Deficient Cells for HIF2α-Driven Mesenchymal Transition. Cell Rep 30:4551-4566.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2020.03.022

Letouzé E, Martinelli C, Loriot C, Burnichon N, Abermil N, Ottolenghi C, Janin M, Menara M, Nguyen AT, Benit P, Buffet A, Marcaillou C, Bertherat J, Amar L, Rustin P, De Reyniès A, Gimenez-Roqueplo A-P, Favier J (2013) SDH mutations establish a hypermethylator phenotype in paraganglioma. Cancer Cell 23:739–752. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2013.04.018

Hoekstra AS, de Graaff MA, Briaire-de Bruijn IH, Ras C, Seifar RM, van Minderhout I, Cornelisse CJ, Hogendoorn PCW, Breuning MH, Suijker J, Korpershoek E, Kunst HPM, Frizzell N, Devilee P, Bayley J-P, Bovée JVMG (2015) Inactivation of SDH and FH cause loss of 5hmC and increased H3K9me3 in paraganglioma/pheochromocytoma and smooth muscle tumors. Oncotarget 6:38777–38788 . https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.6091

Kiss NB, Muth A, Andreasson A, Juhlin CC, Geli J, Bäckdahl M, Höög A, Wängberg B, Nilsson O, Ahlman H, Larsson C (2013) Acquired hypermethylation of the P16INK4A promoter in abdominal paraganglioma: relation to adverse tumor phenotype and predisposing mutation. Endocr Relat Cancer 20:65–78. https://doi.org/10.1530/ERC-12-0267

Yang C, Zhuang Z, Fliedner SMJ, Shankavaram U, Sun MG, Bullova P, Zhu R, Elkahloun AG, Kourlas PJ, Merino M, Kebebew E, Pacak K (2015) Germ-line PHD1 and PHD2 mutations detected in patients with pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma-polycythemia. J Mol Med (Berl) 93:93–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00109-014-1205-7

Lorenzo FR, Yang C, Ng Tang Fui M, Vankayalapati H, Zhuang Z, Huynh T, Grossmann M, Pacak K, Prchal JT (2013) A novel EPAS1/HIF2A germline mutation in a congenital polycythemia with paraganglioma. J Mol Med (Berl) 91:507–512. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00109-012-0967-z

Toledo RA, Qin Y, Srikantan S, Morales NP, Li Q, Deng Y, Kim S-W, Pereira MAA, Toledo SPA, Su X, Aguiar RCT, Dahia PLM (2013) In vivo and in vitro oncogenic effects of HIF2A mutations in pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Endocr Relat Cancer 20:349–359. https://doi.org/10.1530/ERC-13-0101

Pollard PJ, El-Bahrawy M, Poulsom R, Elia G, Killick P, Kelly G, Hunt T, Jeffery R, Seedhar P, Barwell J, Latif F, Gleeson MJ, Hodgson SV, Stamp GW, Tomlinson IPM, Maher ER (2006) Expression of HIF-1alpha, HIF-2alpha (EPAS1), and their target genes in paraganglioma and pheochromocytoma with VHL and SDH mutations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:4593–4598. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2006-0920

Crona J, Taïeb D, Pacak K (2017) New Perspectives on Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma: Toward a Molecular Classification. Endocr Rev 38:489–515. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2017-00062

Oyama T, Harigaya K, Sasaki N, Okamura Y, Kokubo H, Saga Y, Hozumi K, Suganami A, Tamura Y, Nagase T, Koga H, Nishimura M, Sakamoto R, Sato M, Yoshida N, Kitagawa M (2011) Mastermind-like 1 (MamL1) and mastermind-like 3 (MamL3) are essential for Notch signaling in vivo. Development 138:5235–5246. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.062802

Specht K, Zhang L, Sung Y-S, Nucci M, Dry S, Vaiyapuri S, Richter GHS, Fletcher CDM, Antonescu CR (2016) Novel BCOR-MAML3 and ZC3H7B-BCOR Gene Fusions in Undifferentiated Small Blue Round Cell Sarcomas. Am J Surg Pathol 40:433–442. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0000000000000591

Wang X, Bledsoe KL, Graham RP, Asmann YW, Viswanatha DS, Lewis JE, Lewis JT, Chou MM, Yaszemski MJ, Jen J, Westendorf JJ, Oliveira AM (2014) Recurrent PAX3-MAML3 fusion in biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma. Nat Genet 46:666–668. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2989

Guo A-X, Cui J-J, Wang L-Y, Yin J-Y (2020) The role of CSDE1 in translational reprogramming and human diseases. Cell Commun Signal 18:14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12964-019-0496-2

Ju Lee H, Bartsch D, Xiao C, Guerrero S, Ahuja G, Schindler C, Moresco JJ, Yates JR, Gebauer F, Bazzi H, Dieterich C, Kurian L, Vilchez D (2017) A post-transcriptional program coordinated by CSDE1 prevents intrinsic neural differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Nat Commun 8:1456. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-01744-5

Thompson LDR (2002) Pheochromocytoma of the Adrenal gland Scaled Score (PASS) to separate benign from malignant neoplasms: a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic study of 100 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 26:551–566

Gao B, Meng F, Bian W, Chen J, Zhao H, Ma G, Shi B, Zhang J, Liu Y, Xu Z (2006) Development and validation of pheochromocytoma of the adrenal gland scaled score for predicting malignant pheochromocytomas. Urology 68:282–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2006.02.019

Strong VE, Kennedy T, Al-Ahmadie H, Tang L, Coleman J, Fong Y, Brennan M, Ghossein RA (2008) Prognostic indicators of malignancy in adrenal pheochromocytomas: clinical, histopathologic, and cell cycle/apoptosis gene expression analysis. Surgery 143:759–768. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2008.02.007

Szalat A, Fraenkel M, Doviner V, Salmon A, Gross DJ (2011) Malignant pheochromocytoma: predictive factors of malignancy and clinical course in 16 patients at a single tertiary medical center. Endocrine 39:160–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-010-9422-5

Kulkarni MM, Khandeparkar SGS, Deshmukh SD, Karekar RR, Gaopande VL, Joshi AR, Kesari MV, Shelke RR (2016) Risk Stratification in Paragangliomas with PASS (Pheochromocytoma of the Adrenal Gland Scaled Score) and Immunohistochemical Markers. J Clin Diagn Res 10:EC01–EC04. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2016/20565.8419

Stenman A, Svahn F, Hojjat-Farsangi M, Zedenius J, Söderkvist P, Gimm O, Larsson C, Juhlin CC (2018) Molecular Profiling of Pheochromocytoma and Abdominal Paraganglioma Stratified by the PASS Algorithm Reveals Chromogranin B as Associated With Histologic Prediction of Malignant Behavior. Am J Surg Pathol. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0000000000001190

Agarwal A, Mehrotra PK, Jain M, Gupta SK, Mishra A, Chand G, Agarwal G, Verma AK, Mishra SK, Singh U (2010) Size of the tumor and pheochromocytoma of the adrenal gland scaled score (PASS): can they predict malignancy? World J Surg 34:3022–3028. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-010-0744-5

Wachtel H, Hutchens T, Baraban E, Schwartz LE, Montone K, Baloch Z, LiVolsi V, Krumeich L, Fraker DL, Nathanson KL, Cohen DL, Fishbein L (2020) Predicting Metastatic Potential in Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma: A Comparison of PASS and GAPP Scoring Systems J Clin Endocrinol Metab 105. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgaa608

Wu D, Tischler AS, Lloyd RV, DeLellis RA, de Krijger R, van Nederveen F, Nosé V (2009) Observer variation in the application of the Pheochromocytoma of the Adrenal Gland Scaled Score. Am J Surg Pathol 33:599–608. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0b013e318190d12e

A Stenman J Zedenius CC Juhlin 2019 The Value of Histological Algorithms to Predict the Malignancy Potential of Pheochromocytomas and Abdominal Paragangliomas-A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review of the Literature Cancers (Basel) 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11020225

Stenman A, Zedenius J, Juhlin CC (2018) Over-diagnosis of potential malignant behavior in MEN 2A-associated pheochromocytomas using the PASS and GAPP algorithms. Langenbecks Arch Surg 403:785–790. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-018-1679-9

Kimura N, Takayanagi R, Takizawa N, Itagaki E, Katabami T, Kakoi N, Rakugi H, Ikeda Y, Tanabe A, Nigawara T, Ito S, Kimura I, Naruse M, Phaeochromocytoma Study Group in Japan (2014) Pathological grading for predicting metastasis in phaeochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Endocr Relat Cancer 21:405–414. https://doi.org/10.1530/ERC-13-0494

Fishbein L, Wilkerson MD (2018) Chromaffin cell biology: inferences from The Cancer Genome Atlas. Cell Tissue Res 372:339–346. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00441-018-2795-0

Koh J-M, Ahn SH, Kim H, Kim B-J, Sung T-Y, Kim YH, Hong SJ, Song DE, Lee SH (2017) Validation of pathological grading systems for predicting metastatic potential in pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. PLoS One 12:e0187398. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0187398

Hartmann CA, Gross U, Stein H (1992) Cushing syndrome-associated pheochromocytoma and adrenal carcinoma. An immunohistological investigation. Pathol Res Pract 188:287–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0344-0338(11)81206-9

Kimura N, Miura W, Noshiro T, Miura Y, Ookuma T, Nagura H (1994) Ki-67 is an indicator of progression of neuroendocrine tumors. Endocr Pathol 5:223–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02921490

Clarke MR, Weyant RJ, Watson CG, Carty SE (1998) Prognostic markers in pheochromocytoma. Hum Pathol 29:522–526. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0046-8177(98)90070-3

Brown HM, Komorowski RA, Wilson SD, Demeure MJ, Zhu YR (1999) Predicting metastasis of pheochromocytomas using DNA flow cytometry and immunohistochemical markers of cell proliferation: A positive correlation between MIB-1 staining and malignant tumor behavior. Cancer 86:1583–1589

Nagura S, Katoh R, Kawaoi A, Kobayashi M, Obara T, Omata K (1999) Immunohistochemical estimations of growth activity to predict biological behavior of pheochromocytomas. Mod Pathol 12:1107–1111

Gupta D, Shidham V, Holden J, Layfield L (2000) Prognostic value of immunohistochemical expression of topoisomerase alpha II, MIB-1, p53, E-cadherin, retinoblastoma gene protein product, and HER-2/neu in adrenal and extra-adrenal pheochromocytomas. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 8:267–274

Elder EE, Xu D, Höög A, Enberg U, Hou M, Pisa P, Gruber A, Larsson C, Bäckdahl M (2003) KI-67 AND hTERT expression can aid in the distinction between malignant and benign pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Mod Pathol 16:246–255. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MP.0000056982.07160.E3

August C, August K, Schroeder S, Bahn H, Hinze R, Baba HA, Kersting C, Buerger H (2004) CGH and CD 44/MIB-1 immunohistochemistry are helpful to distinguish metastasized from nonmetastasized sporadic pheochromocytomas. Mod Pathol 17:1119–1128. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800160

van der Harst E, Bruining HA, Jaap Bonjer H, van der Ham F, Dinjens WN, Lamberts SW, de Herder WW, Koper JW, Stijnen T, Proye C, Lecomte-Houcke M, Bosman FT, de Krijger RR (2000) Proliferative index in phaeochromocytomas: does it predict the occurrence of metastases? J Pathol 191:175 180. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(200006)191:2<175::AID-PATH615>3.0.CO;2-Z

Pierre C, Agopiantz M, Brunaud L, Battaglia-Hsu S-F, Max A, Pouget C, Nomine C, Lomazzi S, Vignaud J-M, Weryha G, Oussalah A, Gauchotte G, Busby-Venner H (2019) COPPS, a composite score integrating pathological features, PS100 and SDHB losses, predicts the risk of metastasis and progression-free survival in pheochromocytomas/paragangliomas. Virchows Arch 474:721–734. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-019-02553-5

Białas M, Okoń K, Dyduch G, Ciesielska-Milian K, Buziak M, Hubalewska-Dydejczyk A, Sobrinho-Simoes M (2013) Neuroendocrine markers and sustentacular cell count in benign and malignant pheochromocytomas - a comparative study. Pol J Pathol 64:129–135

Unger P, Hoffman K, Pertsemlidis D, Thung S, Wolfe D, Kaneko M (1991) S100 protein-positive sustentacular cells in malignant and locally aggressive adrenal pheochromocytomas. Arch Pathol Lab Med 115:484–487

Schroder HD, Johannsen L (1986) Demonstration of S-100 protein in sustentacular cells of phaeochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Histopathology 10:1023–1033. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2559.1986.tb02539.x

Lloyd RV, Blaivas M, Wilson BS (1985) Distribution of chromogranin and S100 protein in normal and abnormal adrenal medullary tissues. Arch Pathol Lab Med 109:633–635

Papathomas TG, Suurd DPD, Pacak K, Tischler AS, Vriens MR, Lam AK, de Krijger RR (2021) What Have We Learned from Molecular Biology of Paragangliomas and Pheochromocytomas? Endocr Pathol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12022-020-09658-7

van Nederveen FH, Gaal J, Favier J, Korpershoek E, Oldenburg RA, de Bruyn EMCA, Sleddens HFBM, Derkx P, Rivière J, Dannenberg H, Petri B-J, Komminoth P, Pacak K, Hop WCJ, Pollard PJ, Mannelli M, Bayley J-P, Perren A, Niemann S, Verhofstad AA, de Bruïne AP, Maher ER, Tissier F, Méatchi T, Badoual C, Bertherat J, Amar L, Alataki D, Van Marck E, Ferrau F, François J, de Herder WW, Peeters M-PFMV, van Linge A, Lenders JWM, Gimenez-Roqueplo A-P, de Krijger RR, Dinjens WNM (2009) An immunohistochemical procedure to detect patients with paraganglioma and phaeochromocytoma with germline SDHB, SDHC, or SDHD gene mutations: a retrospective and prospective analysis. Lancet Oncol 10:764–771. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70164-0

Gill AJ, Benn DE, Chou A, Clarkson A, Muljono A, Meyer-Rochow GY, Richardson AL, Sidhu SB, Robinson BG, Clifton-Bligh RJ (2010) Immunohistochemistry for SDHB triages genetic testing of SDHB, SDHC, and SDHD in paraganglioma-pheochromocytoma syndromes. Hum Pathol 41:805–814. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2009.12.005

Blank A, Schmitt AM, Korpershoek E, van Nederveen F, Rudolph T, Weber N, Strebel RT, de Krijger R, Komminoth P, Perren A (2010) SDHB loss predicts malignancy in pheochromocytomas/sympathethic paragangliomas, but not through hypoxia signalling. Endocr Relat Cancer 17:919–928. https://doi.org/10.1677/ERC-09-0316

Castelblanco E, Santacana M, Valls J, de Cubas A, Cascón A, Robledo M, Matias-Guiu X (2013) Usefulness of negative and weak-diffuse pattern of SDHB immunostaining in assessment of SDH mutations in paragangliomas and pheochromocytomas. Endocr Pathol 24:199–205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12022-013-9269-4

Kim E, Rath EM, Tsang VHM, Duff AP, Robinson BG, Church WB, Benn DE, Dwight T, Clifton-Bligh RJ (2015) Structural and functional consequences of succinate dehydrogenase subunit B mutations. Endocr Relat Cancer 22:387–397. https://doi.org/10.1530/ERC-15-0099

Papathomas TG, Oudijk L, Persu A, Gill AJ, van Nederveen F, Tischler AS, Tissier F, Volante M, Matias-Guiu X, Smid M, Favier J, Rapizzi E, Libe R, Currás-Freixes M, Aydin S, Huynh T, Lichtenauer U, van Berkel A, Canu L, Domingues R, Clifton-Bligh RJ, Bialas M, Vikkula M, Baretton G, Papotti M, Nesi G, Badoual C, Pacak K, Eisenhofer G, Timmers HJ, Beuschlein F, Bertherat J, Mannelli M, Robledo M, Gimenez-Roqueplo A-P, Dinjens WN, Korpershoek E, de Krijger RR (2015) SDHB/SDHA immunohistochemistry in pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas: a multicenter interobserver variation analysis using virtual microscopy: a Multinational Study of the European Network for the Study of Adrenal Tumors (ENS@T). Mod Pathol 28:807–821. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2015.41

Oudijk L, Gaal J, de Krijger RR (2019) The Role of Immunohistochemistry and Molecular Analysis of Succinate Dehydrogenase in the Diagnosis of Endocrine and Non-Endocrine Tumors and Related Syndromes. Endocr Pathol 30:64–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12022-018-9555-2

Korpershoek E, Favier J, Gaal J, Burnichon N, van Gessel B, Oudijk L, Badoual C, Gadessaud N, Venisse A, Bayley J-P, van Dooren MF, de Herder WW, Tissier F, Plouin P-F, van Nederveen FH, Dinjens WNM, Gimenez-Roqueplo A-P, de Krijger RR (2011) SDHA immunohistochemistry detects germline SDHA gene mutations in apparently sporadic paragangliomas and pheochromocytomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96:E1472-1476. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2011-1043

Menara M, Oudijk L, Badoual C, Bertherat J, Lepoutre-Lussey C, Amar L, Iturrioz X, Sibony M, Zinzindohoué F, de Krijger R, Gimenez-Roqueplo A-P, Favier J (2015) SDHD immunohistochemistry: a new tool to validate SDHx mutations in pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 100:E287-291. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2014-1870

Udager AM, Magers MJ, Goerke DM, Vinco ML, Siddiqui J, Cao X, Lucas DR, Myers JL, Chinnaiyan AM, McHugh JB, Giordano TJ, Else T, Mehra R (2018) The utility of SDHB and FH immunohistochemistry in patients evaluated for hereditary paraganglioma-pheochromocytoma syndromes. Hum Pathol 71:47–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2017.10.013

Tomlinson IPM, Alam NA, Rowan AJ, Barclay E, Jaeger EEM, Kelsell D, Leigh I, Gorman P, Lamlum H, Rahman S, Roylance RR, Olpin S, Bevan S, Barker K, Hearle N, Houlston RS, Kiuru M, Lehtonen R, Karhu A, Vilkki S, Laiho P, Eklund C, Vierimaa O, Aittomäki K, Hietala M, Sistonen P, Paetau A, Salovaara R, Herva R, Launonen V, Aaltonen LA, Multiple Leiomyoma Consortium (2002) Germline mutations in FH predispose to dominantly inherited uterine fibroids, skin leiomyomata and papillary renal cell cancer. Nat Genet 30:406–410. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng849

Favier J, Meatchi T, Robidel E, Badoual C, Sibony M, Nguyen AT, Gimenez-Roqueplo A-P, Burnichon N (2020) Carbonic anhydrase 9 immunohistochemistry as a tool to predict or validate germline and somatic VHL mutations in pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma-a retrospective and prospective study. Mod Pathol 33:57–64. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-019-0343-4

Korpershoek E, Koffy D, Eussen BH, Oudijk L, Papathomas TG, van Nederveen FH, Belt EJT, Franssen GJH, Restuccia DFJ, Krol NMG, van der Luijt RB, Feelders RA, Oldenburg RA, van Ijcken WFJ, de Klein A, de Herder WW, de Krijger RR, Dinjens WNM (2016) Complex MAX Rearrangement in a Family With Malignant Pheochromocytoma, Renal Oncocytoma, and Erythrocytosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 101:453–460. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2015-2592

Stenman A, Svahn F, Welander J, Gustavson B, Söderkvist P, Gimm O, Juhlin CC (2015) Immunohistochemical NF1 analysis does not predict NF1 gene mutation status in pheochromocytoma. Endocr Pathol 26:9–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12022-014-9348-1

Cho NH, Lee HW, Lim SY, Kang S, Jung WY, Park CS (2005) Genetic aberrance of sporadic MEN 2A component tumours: analysis of RET. Pathology 37:10–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313020400024816

Wilzén A, Rehammar A, Muth A, Nilsson O, Tešan Tomić T, Wängberg B, Kristiansson E, Abel F (2016) Malignant pheochromocytomas/paragangliomas harbor mutations in transport and cell adhesion genes. Int J Cancer 138:2201–2211. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.29957

Job S, Draskovic I, Burnichon N, Buffet A, Cros J, Lépine C, Venisse A, Robidel E, Verkarre V, Meatchi T, Sibony M, Amar L, Bertherat J, de Reyniès A, Londoño-Vallejo A, Favier J, Castro-Vega LJ, Gimenez-Roqueplo A-P (2019) Telomerase Activation and ATRX Mutations Are Independent Risk Factors for Metastatic Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma. Clin Cancer Res 25:760–770. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-0139

Dwight T, Flynn A, Amarasinghe K, Benn DE, Lupat R, Li J, Cameron DL, Hogg A, Balachander S, Candiloro ILM, Wong SQ, Robinson BG, Papenfuss AT, Gill AJ, Dobrovic A, Hicks RJ, Clifton-Bligh RJ, Tothill RW (2018) TERT structural rearrangements in metastatic pheochromocytomas. Endocr Relat Cancer 25:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1530/ERC-17-0306

Liu T, Brown TC, Juhlin CC, Andreasson A, Wang N, Bäckdahl M, Healy JM, Prasad ML, Korah R, Carling T, Xu D, Larsson C (2014) The activating TERT promoter mutation C228T is recurrent in subsets of adrenal tumors. Endocr Relat Cancer 21:427–434. https://doi.org/10.1530/ERC-14-0016

Paulsson JO, Mu N, Shabo I, Wang N, Zedenius J, Larsson C, Juhlin CC (2018) TERT aberrancies: a screening tool for malignancy in follicular thyroid tumours. Endocr Relat Cancer 25:723–733. https://doi.org/10.1530/ERC-18-0050

Kumari S, Muthusamy S (2020) SETD2 as a regulator of N6-methyladenosine RNA methylation and modifiers in cancer. Eur J Cancer Prev 29:556–564. https://doi.org/10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000587

Zhou Y, Zheng X, Xu B, Deng H, Chen L, Jiang J (2020) Histone methyltransferase SETD2 inhibits tumor growth via suppressing CXCL1-mediated activation of cell cycle in lung adenocarcinoma. Aging (Albany NY) 12:25189–25206 . https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.104120

Toledo RA, Qin Y, Cheng Z-M, Gao Q, Iwata S, Silva GM, Prasad ML, Ocal IT, Rao S, Aronin N, Barontini M, Bruder J, Reddick RL, Chen Y, Aguiar RCT, Dahia PLM (2016) Recurrent Mutations of Chromatin-Remodeling Genes and Kinase Receptors in Pheochromocytomas and Paragangliomas. Clin Cancer Res 22:2301–2310. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1841

Geli J, Kiss N, Karimi M, Lee J-J, Bäckdahl M, Ekström TJ, Larsson C (2008) Global and regional CpG methylation in pheochromocytomas and abdominal paragangliomas: association to malignant behavior. Clin Cancer Res 14:2551–2559. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1867

Backman S, Maharjan R, Falk-Delgado A, Crona J, Cupisti K, Stålberg P, Hellman P, Björklund P (2017) Global DNA Methylation Analysis Identifies Two Discrete clusters of Pheochromocytoma with Distinct Genomic and Genetic Alterations. Sci Rep 7:44943. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep44943

Hadoux J, Favier J, Scoazec J-Y, Leboulleux S, Al Ghuzlan A, Caramella C, Déandreis D, Borget I, Loriot C, Chougnet C, Letouzé E, Young J, Amar L, Bertherat J, Libé R, Dumont F, Deschamps F, Schlumberger M, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP, Baudin E (2014) SDHB mutations are associated with response to temozolomide in patients with metastatic pheochromocytoma or paraganglioma. Int J Cancer 135:2711–2720. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.28913

Acknowledgements

The author would like to express his sincere gratitude to Dr. Ozgur Mete for organizing the 2021 Endocrine Pathology Society Companion Meeting, as well as for the generous invite to give a lecture and submit a comprehensive summary to this journal.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Karolinska Institute. This work was supported by the Swedish Cancer Society.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

Subsets of illustrations in this article have been featured during a lecture at the 2021 Endocrine Pathology Society Companion Meeting.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Juhlin, C.C. Challenges in Paragangliomas and Pheochromocytomas: from Histology to Molecular Immunohistochemistry. Endocr Pathol 32, 228–244 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12022-021-09675-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12022-021-09675-0