Abstract

Purpose of the Review

Multimorbidity, the presence of two or more comorbidities, is common in patients with heart failure (HF) and worsens clinical outcomes. In Asia, multimorbidity has become the norm rather than the exception. Therefore, we evaluated the burden and unique patterns of comorbidities in Asian patients with HF.

Recent Findings

Asian patients with HF are almost a decade younger than Western Europe and North American patients. However, over two in three patients have multimorbidity. Comorbidities usually cluster due to the close and complex links between chronic medical conditions. Elucidating these links may guide public health policies to address risk factors. In Asia, barriers in treating comorbidities at the patient, healthcare system and national level hamper preventative efforts.

Summary

Asian patients with HF are younger yet have a higher burden of comorbidities than Western patients. A better understanding of the unique co-occurrence of medical conditions in Asia can improve the prevention and treatment of HF.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Heart failure (HF) affected approximately 64.3 million individuals globally in 2017 [1]. The American Heart Association (AHA) estimated annual spending of USD351.2 billion from 2014 to 2015 on HF in the USA alone [2]. Therefore, HF greatly strains the health system [3, 4]. Unfortunately, HF’s prognosis remains grim [5, 6]: the 5-year mortality risk after the diagnosis is 50%, which is worse than many types of cancer [5, 7, 8]. Despite Asia being home to most of the world’s population, most HF data is from Western Europe and North America [9].

Due to widespread population ageing and an increasing comorbidity burden, more people live with chronic diseases [10,11,12]. Individuals with comorbidities often have multimorbidity, defined as having two or more chronic conditions. Comorbidities often share intimate links due to shared disease pathways or pathophysiological processes. People with one comorbidity are often at a higher risk of developing the next. For example, people with diabetes are at an increased risk of developing chronic kidney disease (CKD) [13,14,15,16]. Importantly, people with more comorbidities are more likely to develop HF [17].

In Asia, multimorbidity is becoming increasingly common [18]. In some Indian states, multimorbidity affects almost 10% of individuals [19, 20]. In China, 52% of middle-aged individuals have multimorbidity [21]. Data on patients with prevalent HF showed that approximately two in three Asian patients have at least two comorbidities apart from HF. Chiefly, multimorbidity patterns in patients with HF are associated with worse outcomes [22].

The prevalence of multimorbidity varies by region, highlighting the influence of genetics, socioeconomic determinants and cultural and environmental factors [10, 11, 22, 23]. Many Asian countries, such as Thailand, Singapore and China, underwent a rapid economic development in the past few decades. The rapid economic development led to a ‘Westernization’ of diets and an increase in sedentary lifestyle. These rapid changes occurred in a population where many, especially older, people did not attain formal education. This combination has caused region-specific challenges in patients with a high disease burden but low (health) literacy. Disentangling the shared links between comorbidities can help identify a single or a limited number of common risk factors. These can serve as early primary and secondary prevention targets, reducing the number of quality-adjusted life-years lost, potentially decreasing costs and the burden on health systems. Unfortunately, there are significant barriers to diagnosing and treating risk factors in Asia, especially in lower- and middle-income countries. Therefore, this review will discuss (1) regional patterns of comorbidities and multimorbidity in Asian patients with HF compared with patients from the west and (2) barriers to implementation of treatment and prevention.

Heart Failure Registries in Asia

In contrast to the extensive data regarding HF in Western nations, epidemiologic data are still scarce in Asian patients with HF. Figure 1 shows a non-exhaustive list with previous and current HF registries in Asia. This overview highlights the increasing efforts in collecting data on Asian patients with HF but also emphasizes the significant gap. Some of the first HF registries in Asia were the CHART studies [24] in Japan and the KOR-AHF registry [25] in South Korea. The Asian Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure registry (ASIAN-HF) was the first multinational regional registry prospectively to include Asian patients with both HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) patients. This registry included data from 11 Asian regions (China, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan and Thailand) [26]. There have been various country-specific studies, such as the Kerala-HF registry [27] in India, the ATTRaCT and SHOP studies in Singapore [28, 29] and CHINA-HF [30] in China. However, there are still few large HF registries, including many Asia regions (Central Asia and West Asia) or countries (Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand), which are crucial to determining the HF trend and risk factors [31,32,33,34].

Prevalence of Leading Comorbidities in Patients with Heart Failure from Asia Compared to Western Europe and North America

Because the comorbidity burden differs significantly between HFrEF and HFpEF [35, 36], the comorbidity patterns of patients with HFrEF and HFpEF are discussed separately.

Heart Failure with a Reduced Ejection Fraction (HFrEF)

The Prospective Comparison of ARNI with ACEI to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure (PARADIGM-HF) trial was among the first randomized controlled clinical trials to include a significant number of patients with HFrEF from the Asia–Pacific region, which included China, Hong Kong, India, Israel, South Korea, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Taiwan. Table 1 shows that patients in PARADIGM-HF from the Asia–Pacific region were younger, had a lower body mass index (BMI), lower prevalence of atrial fibrillation (AF) and a lower prevalence of hypertension than patients from Western Europe or North America.

The ASIAN-HF was one of Asia’s first multinational ‘real-world’ HF registries highlighting the unique characteristics of Asian patients with HFrEF. This registry prospectively enrolled more than 6300 patients from 46 centres across 11 Asian regions [26, 38, 44]. The registries’ results highlighted the young age of Asian patients with HF. Table 1 shows that the mean age of patients from South Asia was only 58 years compared to 65 or 66 in the European Society of Cardiology Long-Term registry (ESC-HF-LT) and Change the Management of Patients with Heart Failure registry (CHAMP-HF) registry, respectively. Importantly, the ASIAN-HF registry highlighted the considerable regional heterogeneity within Asia: differences in age and comorbidities were as significant among Asian regions as between Asian and Western European registries (Table 1).

Despite their relative youth, Asian patients had a high comorbidity burden [38]. Notably, Southeast Asian patients were younger but had the highest prevalence of comorbidities, such as CKD and diabetes, compared to patients from Northeast Asia and South Asia (India) [22]. Data from other Asian registries mirrored these data. Japanese and Korean patients in the CHART-2 and KOR-AHF [39, 40] registries, respectively, had a similar mean age as patients from European [42] or North America [45]. They were older than South or Southeast Asian patients. Notably, patients from Korea and Japan had a high prevalence of hypertension, which is also true for their general population [46]. In contrast, patients with HFrEF from CHINA-HF [30] and the Trivandrum HF registry [41] (India) were younger than patients in Northeast Asian registries. Notably, Indian patients had a very high prevalence of diabetes [41], highlighting the significant burden of this comorbidity on that region.

Heart Failure with a Preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF)

PARAGON-HF was the first multinational phase 3 HFpEF trial, including a significant number of patients from Asia. Regional differences in PARAGON-HF largely mirrored those in PARADIGM-HF: patients from Asia were younger yet had a similar high comorbidity burden as those from Western Europe and North America [47]. Notably in PARAGON-HF was the high prevalence of diabetes in Asia despite having a lower mean body mass index (BMI) than other regions.

Table 2 shows that differences among regional registries mirror differences in PARAGON-HF. The age gap between Asian and Western countries was larger than in HFrEF. Patients from South Asia and Southeast Asia in ASIAN-HF were almost a decade younger than patients from the Swedish Heart Failure registry (SWEDE-HF) or the Framingham Heart Study (FHS). Despite their relative youth, these patients had a high comorbidity burden. A previous study investigating younger patients with HFpEF in Asia highlighted that younger Asian patients were more likely to be men, of Malay or Indian origin, and with a high prevalence of obesity [48]. The worse outcomes of younger patients than age- and sex-matched controls confirmed that these patients truly had HF [48]. The unique characteristics of younger patients with HFpEF (male, Asian, obese) were further confirmed in a combined study of the Treatment of Preserved Cardiac Function Heart Failure with an Aldosterone Antagonist trial (TOPCAT), Candesartan in Heart failure: Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and morbidity study (CHARM-Preserved) and Irbesartan in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction Study (I-PRESERVE) studies [49].

Regional Differences in Patterns of Multimorbidity

Several studies have highlighted the burden, patterns and consequences of HF patients with multimorbidity [20, 52]. In the ASIAN-HF registry, the latent class analysis revealed five multimorbidity groups with distinct geographic distributions across Asia, each affecting patients’ quality of life and health outcomes differently. First, there was an elderly/AF (old and more atrial fibrillation (AF)) pattern, primarily consisting of patients from Hong Kong, Japan and Korea. Second is a metabolic (obese, hypertensive and diabetic) pattern, most prevalent in Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Taiwan. Third is a young (younger and lesser comorbidities) pattern, most prevalent in China, India, Japan, Korea and Thailand. Fourth is an ischemic (coronary artery disease (CAD) and ischemic aetiology) pattern, most prevalent in India, Indonesia and Malaysia. Fifth is a lean-diabetic (diabetic and low BMI) pattern, most commonly found in Hong Kong, Malaysia and Singapore. The lean-diabetic (predominantly type II diabetes) seemed unique to Asia and was not seen in previous studies investigating multimorbidity. For example, Gulea et al. identified five multimorbidity patterns in the USA: low-burden (minimal comorbidities), metabolic-vascular (diabetic, obese and vascular disease), anaemic (cancer and depression), ischemic (oldest) and metabolic (young, diabetic and obese) [53]. In Spain, a previous study identified six groups which largely mirror those found in the USA but did not include a lean-diabetic phenotype [54].

The ‘thrifty gene’ hypothesis might explain the existence of a lean-diabetic phenotype. Southeast Asia has undergone a rapid epidemiological transition due to economic development and westernization of diet [55]. The ‘thrifty gene’ hypothesis suggests that individuals who can easily store extra energy had an evolutionary advantage during previous famines [56]. The existence of a lean-diabetic phenotype might further be explained by the greater propensity of Asians to store fat in the visceral space. In a study investigating the nexus between BMI and abdominal fat, patients with a low BMI but high waist-to-height ratio had the worst quality of life and the highest prevalence of diabetes, emphasizing the unique role of excess visceral fat in Asian patients with HF [57]. A study investigating the role of epicardial fat, which is part of the visceral fat depot, found that increased levels of epicardial fat were associated with adverse cardiac remodelling and fibrosis [58]. This might also explain why the prevalence of diabetes is significantly higher in Asians than in White patients for any given BMI [59].

Recognizing the shared links between comorbidities and identifying common risk factors can guide public health investments and preventative efforts. A previous study, performed in the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health (ALSWH), characterized the longitudinal progression of three conditions and multimorbidity. The authors found that the odds of developing new conditions were significantly higher in women who already had pre-existing comorbidities than those without any [60]. These critical results highlighted that comorbidities cluster over time and that progression of multimorbidity is likely not linear but exponential. A longitudinal study using data from general practices in the UK showed similar results [61]. In this study, diabetes was the most common initial onset condition, and South Asians were at a significantly higher risk of developing diabetes [61]. Collectively, these results highlight the importance of identifying shared links between comorbidities and emphasize the increased risk of (South and Southeast) Asians developing multimorbidity.

Treatment of Comorbidities in Asia: Barriers to Implementation

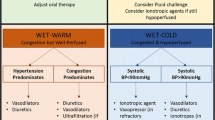

The first step is to recognize the importance of multimorbidity and different early onset conditions (Fig. 2). Adequate treatment and prevention of comorbidities to reduce the prevalence of multimorbidity and HF are the logical consequence, but there are significant patient, healthcare professional and policy-level barriers in Asia that may inhibit adequate care and prevention.

Summary figure of various healthcare issues, barriers and possible solutions at different levels of the health system. Key barriers in Asian population include socio-cultural beliefs and often low education/health literacy of (elderly) patients, fragmented and weak primary healthcare systems and high out-of-pocket costs for patients and carers

In many Asian countries, patients often have insufficient knowledge and understanding of chronic disease due to low educational levels, persistent myths and beliefs and financial challenges. As a result, (often older) patients tend to believe in natural remedies and traditional herbal practitioners as cheaper alternatives to (‘Western’) medicine, which often leads to misconceptions and worse health outcomes [62, 63]. In addition, Asian patients seem to face even more significant difficulties in adopting to a healthier lifestyle than elsewhere. While attempting to modify their habits, most reverted to their original lifestyles, and one of the most difficult habits to change was their dietary regimen [63]. Improved patient education on the importance of a healthy lifestyle, smoking cessation and medication adherence are vital interventions for these issues. Policy makers should promote low-cost healthy diets (lower salt, sugar and oil content in foods) and increased physical activities to alleviate the CVD epidemic. These interventions are often highly cost-efficient [64, 65].

Implementing preventive policies and chronic disease management in a financially sustainable way requires strengthening primary care systems to provide low-cost personalized care by providers close to local communities [66]. In South and Southeast Asia, many countries have a weak primary care system. Primary care physicians often operate as single private practices and have a limited role in chronic disease management and prevention [67]. Instead, patients often self-refer to specialized hospitals, leading to fragmented care of multimorbidity, increased costs and additional financial barriers to care.

Strengthening primary care would require a policy-level commitment with sufficient financial investments to enable primary care physicians to manage chronic diseases. This can further be supported by digital technologies, which enable the integration of electronic health records with secondary and tertiary care providers, which is key for chronic disease management.

Conclusion

Asian patients with HF are up to a decade younger than Western patients. Despite their relative youth, multimorbidity is common. Having two or more comorbidities is associated with an increased risk of developing HF and worsens outcomes and quality of life of people living with HF. Asia is home to a unique lean-diabetic multimorbidity HF phenotype with worse outcomes. A better understanding of the unique co-occurrence of medical conditions in Asia can improve the prevention and treatment of HF. However, there remains a significant unmet need to address barriers in treating comorbidities at the patient, healthcare system and national level.

References

James SL, Abate D, Abate KH, Abay SM, Abbafati C, Abbasi N, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1789–858.

Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2019 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139(10):e56-66.

Lippi G, Sanchis‐Gomar F. Global epidemiology and future trends of heart failure. AME Med J. 2020; 5(15):1–6.

Roberts NLS, Mountjoy-Venning WC, Anjomshoa M, Banoub JAM, Yasin YJ. GBD 2017 Disease and injury incidence and prevalence collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for. Lancet (British Ed). 2019;393(10190):E44–E44.

Stewart S, MacIntyre K, Hole DJ, Capewell S, McMurray JJV. More, “malignant” than cancer? Five-year survival following a first admission for heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2001;3(3):315–22.

Allen LALA, Yager JEJE, Funk MJMJ, Levy WCWC, Tulsky JAJA, Bowers MTMT, et al. Discordance between patient-predicted and model-predicted life expectancy among ambulatory heart failure patients. JAMA. 2008;299(21):2533–42.

Jones NR, Roalfe AK, Adoki I, Hobbs FDR, Taylor CJ. Survival of patients with chronic heart failure in the community: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Hear Fail. 2019;21(11):1306–25.

Jones NR, Hobbs FDR, Taylor CJ. Prognosis following a diagnosis of heart failure and the role of primary care: a review of the literature. BJGP Open. 2017;1(3):bjgpopen17X101013-bjgpopen17X101013.

Groenewegen A, Rutten FH, Mosterd A, Hoes AW. Epidemiology of heart failure. Eur J Hear Fail. 2020;22(8):1342–56.

Bezerra de Souza DL, Oliveras-Fabregas A, Espelt A, Bosque-Prous M, de Camargo Cancela M, Teixidó-Compañó E, et al. Multimorbidity and its associated factors among adults aged 50 and over: a cross-sectional study in 17 European countries. PLoS One. 2021;16(2):e0246623–e0246623.

Palladino R, Lee JT, Ashworth M, Triassi M, Millett C. Associations between multimorbidity, healthcare utilization and health status: evidence from 16 European countries. Age Ageing. 2016;45(3):431–5.

Abebe F, Schneider M, Asrat B, Ambaw F. Multimorbidity of chronic non-communicable diseases in low- and middle-income countries: a scoping review. J Comorb. 2020;10:2235042X20961919-2235042X20961919.

Johnston MC, Crilly M, Black C, Prescott GJ, Mercer SW. Defining and measuring multimorbidity: a systematic review of systematic reviews. Eur J Public Heal. 2019;29(1):182–9.

Harrison C, Fortin M, van den Akker M, Mair F, Calderon-Larranaga A, Boland F, et al. Comorbidity versus multimorbidity: why it matters. J Comorb. 2021;11:2633556521993993–2633556521993993.

Haug N, Deischinger C, Gyimesi M, Kautzky-Willer A, Thurner S, Klimek P. High-risk multimorbidity patterns on the road to cardiovascular mortality. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):44.

Pecoits-Filho R, Abensur H, Betônico CCR, MacHado AD, Parente EB, Queiroz M, et al. Interactions between kidney disease and diabetes: dangerous liaisons. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2016;8(1):50.

Brouwers FP, De Boer RA, Van Der Harst P, Voors AA, Gansevoort RT, Bakker SJ, et al. Incidence and epidemiology of new onset heart failure with preserved vs. reduced ejection fraction in a community-based cohort: 11-year follow-up of PREVEND. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(19):1424–31.

Feng X, Kelly M, Sarma H. The association between educational level and multimorbidity among adults in Southeast Asia: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(12):e0261584–e0261584.

Singh K, Patel SA, Biswas S, Shivashankar R, Kondal D, Ajay VS, et al. Multimorbidity in South Asian adults: prevalence, risk factors and mortality. J Public Heal. 2019;41(1):80–9.

Tromp J, Tay WT, Ouwerkerk W, Teng THK, Yap J, MacDonald MR, et al. Multimorbidity in patients with heart failure from 11 Asian regions: a prospective cohort study using the ASIAN-HF registry. Rahimi K, editor. PLoS Med. 2018;15(3):e1002541.

Wang X, Yao S, Wang M, Cao G, Chen Z, Huang Z, et al. Multimorbidity among two million adults in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17(10):3395.

Lam CSP, Teng T-HK, Tay WT, Anand I, Zhang S, Shimizu W, et al. Regional and ethnic differences among patients with heart failure in Asia: the Asian sudden cardiac death in heart failure registry. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(41):3141–53.

Barnett PhDK, Mercer Prof SW, Norbury MBChBM, Watt Prof G, Wyke Prof S, Guthrie PB. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2012;380(9836):37–43.

Shiba N, Shimokawa H. Chronic heart failure in Japan: implications of the CHART studies. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2008;4(1):103–13.

Lee SE, Cho HJ, Lee HY, Yang HM, Choi JO, Jeon ES, et al. A multicentre cohort study of acute heart failure syndromes in Korea: rationale, design, and interim observations of the Korean Acute Heart Failure (KorAHF) registry. Eur J Heart Fail. 2014;16(6):700–8.

Lam CSP, Anand I, Zhang S, Shimizu W, Narasimhan C, Park SW, et al. Asian Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure (ASIAN-HF) registry. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15(8):928–36.

Harikrishnan S, Sanjay G, Anees T, Viswanathan S, Vijayaraghavan G, Bahuleyan CG, et al. Clinical presentation, management, in-hospital and 90-day outcomes of heart failure patients in Trivandrum, Kerala, India: the Trivandrum Heart Failure Registry. Eur J Heart Fail. 2015;17(8):794–800.

Agency for Science, Technology and Research. Asian Network for Translational Research and Cardiovascular Trials (ATTRACT) [Internet]. [Singapore]; 2022 Apr 1; cited 2022 Apr 11]. Available from: https://www.a-star.edu.sg/attract.

Santhanakrishnan R, Ng TP, Cameron VA, Gamble GD, Ling LH, Sim D, et al. The Singapore heart failure outcomes and phenotypes (SHOP) study and prospective evaluation of outcome in patients with heart failure with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction (PEOPLE) study: rationale and design. J Card Fail. 2013;19(3):156–62.

Lyu S, Yu L, Tan H, Liu S, Liu X, Guo X, et al. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction: insights from a multi-centre registry study in China. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2019;19(1):209.

Siswanto BB. Heart Failure in Indonesia. J Card Fail. 2013;19(10):S108.

Siswanto BB, Radi B, Kalim H, Santoso A, Suryawan R, Erwinanto, et al. Heart failure in NCVC Jakarta and 5 hospitals in Indonesia. CVD Prev Control. 2010;5(1):35–8.

Ghapar AKA, Ross NT, Lee CY, Muhammad FSI, Lawi FM, Liew HB, et al. Treatment pattern and outcomes of patients hospitalized for HF: interim review of National Malaysian Heart Failure (MYHF) registry. Int J Cardiol. 2021;345:38.

Krittayaphong R, Laothavorn P, Hengrussamee K, Sanguanwong S, Kunjara-Na-Ayudhya R, Rattanasumawong K, et al. Ten-year survival and factors associated with increased mortality in patients admitted for acute decompensated heart failure in Thailand. Singapore Med J. 2020;61(6):320–6.

Ather S, Chan W, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, Ramasubbu K, Zachariah AA, et al. Impact of noncardiac comorbidities on morbidity and mortality in a predominantly male population with heart failure and preserved versus reduced ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(11):998–1005.

Iorio A, Senni M, Barbati G, Greene SJ, Poli S, Zambon E, et al. Prevalence and prognostic impact of non-cardiac comorbidities in heart failure outpatients with preserved and reduced ejection fraction: a community-based study. Eur J Hear Fail. 2018;20(9):1257–66.

Kristensen SL, Martinez F, Jhund PS, Arango JL, Belohlavek J, Boytsov S, et al. Geographic variations in the PARADIGM-HF heart failure trial. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(41):3167–74.

MacDonald MR, Tay WT, Teng THK, Anand I, Ling LH, Yap J, et al. Regional variation of mortality in heart failure with reduced and preserved ejection fraction across Asia: outcomes in the ASIAN-HF Registry. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(1): e012199.

Tsuji K, Sakata Y, Nochioka K, Miura M, Yamauchi T, Onose T, et al. Characterization of heart failure patients with mid-range left ventricular ejection fraction—a report from the CHART-2 Study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19(10):1258–69.

Kang J, Park JJ, Cho YJ, Oh IY, Park HA, Lee SE, et al. Predictors and prognostic value of worsening renal function during admission in HFpEF Versus HFrEF: data from the KorAHF (Korean acute heart failure) registry. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(6):e007910.

Harikrishnan S, Jeemon P, Ganapathi S, Agarwal A, Viswanathan S, Sreedharan M, et al. Five-year mortality and readmission rates in patients with heart failure in India: results from the Trivandrum Heart Failure Registry. Int J Cardiol. 2021;326:139–43.

Crespo-Leiro MG, Anker SD, Maggioni AP, Coats AJ, Filippatos G, Ruschitzka F, et al. European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure Long-Term Registry (ESC-HF-LT): 1-year follow-up outcomes and differences across regions. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18(6):613–25.

DeVore AD, Mi X, Thomas L, Sharma PP, Albert NM, Butler J, et al. Characteristics and treatments of patients enrolled in the CHAMP-HF registry compared with patients enrolled in the PARADIGM-HF trial. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(12):e009237.

Lam CS, Anand I, Zhang S, et al. Asian Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure (ASIAN-HF) registry. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15(8):928–936.

Greene SJ, Butler J, Albert NM, DeVore AD, Sharma PP, Duffy CI, et al. Medical therapy for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: the CHAMP-HF Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(4):351–66.

Hisamatsu T, Segawa H, Kadota A, Ohkubo T, Arima H, Miura K. Epidemiology of hypertension in Japan: beyond the new 2019 Japanese guidelines. Hypertens Res. 2020;43(12):1344–51.

Tromp J, Claggett BL, Liu J, Jackson AM, Jhund PS, Køber L, et al. Global differences in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the PARAGON-HF Trial. Circ Heart Fail. 2021;14(4): e007901.

Tromp J, MacDonald MR, Ting Tay W, Teng THK, Hung CL, Narasimhan C, et al. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in the young. Circulation. 2018;138(24):2763–73.

Tromp J, Shen L, Jhund PS, et al. Age-Related Characteristics and Outcomes of Patients with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(5):601–612.

Alehagen U, Benson L, Edner M, Dahlstrom U, Lund LH. Association between use of statins and mortality in patients with heart failure and ejection fraction of ≥50%. Circ Hear Fail. 2015;8(5):862–70.

Lee DS, Gona P, Vasan RS, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ, Wang TJ, et al. Relation of disease pathogenesis and risk factors to heart failure with preserved or reduced ejection fraction: insights from the Framingham Heart Study of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Circulation. 2009;119(24):3070–7.

Rahimi K, Lam CSP, Steinhubl S. Cardiovascular disease and multimorbidity: a call for interdisciplinary research and personalized cardiovascular care. PLoS Med. 2018;15(3):e1002545–e1002545.

Gulea C, Zakeri R, Quint JK. Model-based comorbidity clusters in patients with heart failure: association with clinical outcomes and healthcare utilization. BMC Med. 2021;19(1):9.

Gimeno-Miguel A, Gracia Gutiérrez A, Poblador-Plou B, Coscollar-Santaliestra C, Pérez-Calvo JI, Divo MJ, et al. Multimorbidity patterns in patients with heart failure: an observational Spanish study based on electronic health records. BMJ Open. 2019;9(12):e033174–e033174.

Omran AR. The epidemiologic transition theory. A preliminary update. J Trop Pediatr. 1983;29(6):305–16.

Sellayah D, Cagampang FR, Cox RD. On the evolutionary origins of obesity: a new hypothesis. Endocrinology. 2014;155(5):1573–88.

Chandramouli C, Tay WT, Bamadhaj NS, Tromp J, Teng THK, Yap JJL, et al. Association of obesity with heart failure outcomes in 11 Asian regions: a cohort study. Rahimi K, editor. PLoS Med. 2019;16(9):e1002916.

Tromp J, Bryant JA, Jin X, van Woerden G, Asali S, Yiying H, et al. Epicardial fat in heart failure with reduced versus preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021;23(5):835–8.

Bank IEM, Gijsberts CM, Teng THK, Benson L, Sim D, Yeo PSD, et al. Prevalence and clinical significance of diabetes in asian versus white patients with heart failure. JACC Hear Fail. 2017;5(1):14–24.

Xu X, Mishra GD, Dobson AJ, Jones M. Progression of diabetes, heart disease, and stroke multimorbidity in middle-aged women: A 20-year cohort study. PLoS Med. 2018;15(3):e1002516.

Ashworth M, Durbaba S, Whitney D, Crompton J, Wright M, Dodhia H. Journey to multimorbidity: longitudinal analysis exploring cardiovascular risk factors and sociodemographic determinants in an urban setting. BMJ Open. 2019;9(12):e031649.

George CE, Ramadas D, Norman G, Mukherjee D, Rao T. Barriers to cardiovascular disease risk reduction: does physicians’ perspective matter? Indian Hear J. 2015;68(3):278–85.

Negarandeh R, Aghajanloo A, Seylani K. Barriers to self-care among patients with heart failure: a qualitative study. J caring Sci. 2020;10(4):196–204.

Martinez-Amezcua P, Haque W, Khera R, Kanaya AM, Sattar N, Lam CSP, et al. The upcoming epidemic of heart failure in South Asia. Circ Hear Fail. 2020;13(10):e007218–e007218.

Collier J, Kienzler H. Barriers to cardiovascular disease secondary prevention care in the West Bank, Palestine - a health professional perspective. Confl Heal. 2018;12(1):27.

Tan CC, Lam CSP, Matchar DB, Zee YK, Wong JEL. Singapore’s healthcare system: key features, challenges, and shifts. Lancet. 2021;398(10305):1091–104.

Asian Pacific Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. Strengthening primary health care for the prevention and management of cardiometabolic disease in low- and middle-income countries [Internet]. [India]; 2019 Oct 21; cited 2021 Apr 11]. Available from: https://apo.who.int/publications/i/item/9789290227366.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

JT is supported by the National University of Singapore Start-up grant, the tier 1 grant from the Ministry of Education and the CS-IRG New Investigator Grant from the National Medical Research Council; has received consulting or speaker fees from Daiichi-Sankyo, Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche Diagnostics and Us2.ai; and owns patent US-10702247-B2 unrelated to the present work.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The editors would like to thank Dr. Christiane Angermann for taking the time to handle the review of this manuscript

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ang, N., Chandramouli, C., Yiu, K. et al. Heart Failure and Multimorbidity in Asia. Curr Heart Fail Rep 20, 24–32 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11897-023-00585-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11897-023-00585-2