Opinion statement

Informal caregivers invest a significant amount of time and effort to provide cancer patients with physical, psychological, information, and social support. These challenging tasks can harm their own health and well-being, while a series of social-ecological factors may also influence the outcomes of cancer caregiving. Several instruments have been developed to help clinicians and researchers understand the multi-dimensional needs and concerns of caregivers. A growing body of evidence indicates that supportive interventions including psychoeducation, skills training, and therapeutic counseling can help improve the burden, information needs, coping strategies, physical functioning, psychological well-being, and quality of life of caregivers. However, there is difficulty in translating research evidence into practice. For instance, some supportive interventions tested in clinical trial settings are regarded as inconsistent with the actual needs of caregivers. Other significant considerations are the lack of well-trained interdisciplinary teams for supportive care provision and insufficient funding. Future research should include indicators that can attract decision-makers and funders, such as improving the efficient utilization of health care services and satisfaction of caregivers. It is also important for researchers to work closely with key stakeholders, to facilitate evidence dissemination and implementation, to benefit caregivers and the patient.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With socioeconomic transitions and an increasingly aging population, cancer burden is increasing rapidly. Global cancer statistics show that over 19 million people were newly diagnosed with cancer in the year of 2020, and that this number is expected to rise to 28 million in the coming two decades [1]. Cancer and its treatments can cause various adverse effects that affect quality of life of patients and can result in extensive care needs [2]. Due to limited resources, the current formal health care system cannot cater to all domains of cancer care needs [3]. Therefore, informal caregiving becomes an important asset for supporting patients throughout cancer survivorship or into palliative care.

The persons who engage in informal caregiving are mainly the family members, relatives, friends, or neighbors of patients. They provide physical, emotional, social, and financial supports to meet the complex care needs of cancer patients without compensation [4••]. A scoping review of 19 studies indicates that informal caregivers spend much time and energy in taking care of cancer patients, equivalent to a monetary cost of over $2000 per month [5]. Having an informal caregiver is associated with better coping capabilities and healthier lifestyle habits in cancer patients [6]. However, many caregivers perceive that they are not well prepared to navigate through the challenges brought by cancer caregiving [7]. Previous reviews have highlighted the importance of understanding the unmet needs of informal cancer caregivers and developing appropriate strategies to improve their well-being [3, 8, 9••]. In this paper, the latest evidence regarding the role, function, experience, and unmet needs of informal cancer caregivers has been reviewed, as well as the innovations in measurements and interventions to inform future practice and research.

Role and function of informal cancer caregivers: juggling multiple and complex roles

Caregivers are essential coordinators in facilitating communication between cancer patients and health professionals [10, 11••] and seeking information to support decision-making in treatment [12•, 13, 14] after the receipt of a cancer diagnosis. In family-centric communities, caregivers, especially spouses and family caregivers, usually serve as gatekeepers and buffers in disclosing the cancer diagnosis to alleviate the fear and shock of the patient [14,15,16]. They also may act as the key treatment decision-makers for cancer patients [16, 17]. Parents who bear the primary responsibility for treatment decisions for pediatric or adolescent patients with cancer also feel responsible for seeking cancer- and treatment-related information and evaluating the information credibility [18, 19].

Once complex and long-lasting cancer treatment is initiated, caregivers often need to provide care that requires certain professional skills, (such as administering oral medications, managing inserted catheters, and providing nutritional support [11••, 20]), which are crucial for improved patient outcomes. Caregivers may also take on the task of fundraising if patients face financial difficulties caused by cancer care [11••, 21]. When cancer patients experience psychological distress and adverse effects associated with cancer and the corresponding treatment, caregivers would be responsible for providing emotional support, managing symptoms, and assisting with daily activities [11••, 14, 21,22,23]. They may also need to substitute the role of the patient in doing housework and caring for dependent children, especially if the patient experiences functional decline [14]. After completing treatment, caregivers are responsible for helping the patient return to the “new normal” of life, study, or work [14, 24] and maintain cancer surveillance [25]. In end-of-life care, family caregiver effort is key to supporting cancer patients die at their preferred place of care [26].

Impact of caregiving on informal cancer caregivers

Since caring for cancer patients is often difficult, caregivers can experience caregiver burden and have unmet needs in terms of time constraints, self-development difficulties, physical health problems, social isolation, emotional distress, and economic issues [27, 28]. To cope with such stressful conditions, caregivers need informational, practical, psychosocial, and financial support from health professionals, other family members, social networks, non-governmental organizations, and/or government agencies [29,30,31,32,33]. Additionally, partner or spousal caregivers may also have information and communication needs with regard to sexual health [34, 35] and fertility [34, 36]. High levels of unmet need can exacerbate caregivers’ burden of cancer caregiving and jeopardize their psychophysiological function [37] and quality of life [28, 38, 39]. Heavy caregiver burden may foster unhealthy behaviors such as alcohol [40, 41] and drug [40] use, which can increase the risk of developing metabolic syndrome including high levels of nonfasting glucose and triglycerides, low level of high-density lipoprotein, high blood pressure, and abdominal girth [42]. Caregiver burden and the depressive symptoms associated with caregiving can negatively affect the physical and mental health as well as quality of life of those they care for [43, 44].

Nevertheless, caregiving for cancer patients may also bring positive outcomes. Bloom and colleagues found that some caregivers of adults with cancer expressed more positive emotions than negative ones in their journal entries on online social media [27]. Caregivers often highlight the rewarding experience of caring and the joy of normal daily life [11••, 27, 45]. The relationship between caregiver and patient may become more intimate due to a grateful experience of mutual support [34]. These positive aspects of cancer caregiving were found to be associated with greater personal growth [46] and higher sense of happiness compared to the general population [47]. Additionally, fear of cancer recurrence may promote the caregivers own adherence to cancer screening [48].

Recent longitudinal studies employing either quantitative or qualitative designs showed that although the caregiver burden and unmet needs tend to vary over time, they may persist throughout the cancer illness and caregiving trajectory [49, 50•, 51•]. Caregivers who have substantial caregiver burden and psychological distress before the initiation of treatment are likely to experience higher levels of caregiver burden and psychological distress after termination of chemotherapy [49, 52]. According to a longitudinal qualitative study, family caregivers constantly worry about the prognosis of the patient throughout the course of chemotherapy, which causes anxiety [50•]. With the passage of time, caregivers gain more experience and skills for cancer caregiving [50•], and their information needs tend to be met to a certain extent [51•]. However, due to the emerging adverse effects of treatment and the often the progression of cancer, caregivers may need continuous support from the oncology team [50•]. Their financial burden can continue throughout the course of cancer treatment [50•, 53]. They may experience a strong sense of loneliness throughout the treatment journey [54].

If cancer treatment becomes ineffective, caregivers are likely to develop negative emotions such as shock, regret, frustration, and guilt [55]. They might be hostile to health professionals if they feel that the prognosis of the patient and comfort care options were not realistically discussed [55, 56]. Some caregivers who have erroneous expectations about the benefit of treatment may wish to continue with more chemotherapy, while some may face a dilemma between supporting the preferences of the patient and their own opinion [55, 57]. Caregivers may have more positive memories if they perceive that what they have done has fulfilled the wishes of the patient, despite the experience of emotional difficulties during the end-of-life transition [55, 56]. Although most caregivers will gradually return to normal life after the death of the patient, some may experience severe post-loss distress, which can result in higher levels of anxiety and depression [58,59,60]. Parents of children who have died of cancer are likely to experience post-loss distress and prolonged grief symptoms due to regret and unfinished business [61]. Bereaved family caregivers also tend to have a lower quality of life compared with the general population [58, 59].

Factors influencing informal cancer caregiving

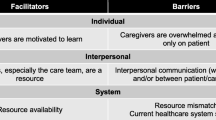

The impact of cancer caregiving on caregivers can be influenced by several factors. A literature review classified the factors into four domains: caregiver-related (e.g., gender, age, and socio-economic status), patient-related (e.g., age, health status, and quality of life), the caregiver-patient dyadic (e.g., relationship between caregivers and the cancer patient), and caregiving-related factors (e.g., perceived caregiver burden) [9••]. A growing body of research in recent years demonstrated the mechanisms of these factors in informal cancer caregiving and added knowledge regarding factors beyond the four domains, such as the caregiver-oncologist relationship, organizational support, and social norms. Given that informal cancer caregiving involves extensive interactions between stakeholders and their environment, the review by McLeroy and colleagues employed a Social-Ecological Model [62] to explain the factors associated with informal cancer caregiving. According to this model, factors influencing outcomes of informal cancer caregiving can be divided into intrapersonal, interpersonal, institutional, community, and policy factors (Fig. 1).

Intrapersonal factors

It is well documented that female caregivers are more likely to develop mental health problems and caregiver burden compared to male caregivers [9••, 63•]. However, male partners or husbands of female cancer patients who hold the norms of masculinity and face the dilemma of expressing emotional distress are also likely to develop high levels of caregiver burden and depressive symptoms [34, 64]. The negative side of masculinity in the context of cancer caregiving may lead to a higher risk of unhealthy behaviors, such as smoking and binge drinking, in male caregivers [41].

Age of the caregiver is another important factor relevant to cancer caregiving outcomes [9••, 63•]. Caregivers of younger age may have high levels of unmet need regarding caregiving skills training than those at older age due to less caregiving experience [65]. Younger caregivers are more prone to develop psychological symptoms, while older caregivers are more likely to experience physical health problems [9••, 63•, 66]. However, a recent study conducted in Italy found that compared with younger (age < 65 years) caregivers, elderly (age ≥ 65 years) caregivers experienced higher burden of personal development when supporting cancer patients at the end-of-life, which may be associated with a pessimistic perspective on future life [67]. This indicates that the mental health of elderly caregivers should not be overlooked.

The socioeconomic status of caregivers such as education, occupation, and income are also significant intrapersonal factors that may influence cancer caregiving outcomes [9••, 63•]. Studies indicated that full-time employment and lower educational level can predict greater anxiety and depression in caregivers [68]. However, other recent studies found that higher income and educational level were significantly associated with greater caregiver burden and lower quality of life [21, 28]. This implies that caregivers are facing difficulty in balancing career and cancer caregiving, which can affect their social and psychological well-being [69]. A secondary analysis of data from the Improving Communication in Older Cancer Patients and Their Caregivers (COACH) study suggested that the negative effect of lower education level on caregiver burden was particularly prominent among caregivers who were from rural areas [70]. The lower educated caregivers would have more unmet needs in palliative care and during bereavement [30].

Other identified intrapersonal factors are the coping strategies, self-efficacy, and resilience of caregivers [60, 71]. Maladaptive coping by caregivers is associated with a poorer health profile in cancer survivorship and end-of-life care [68, 72] and prolonged grief symptoms in bereavement [72, 73]. Caregivers with decreased self-efficacy and resilience experience a higher level of caregiver burden, more depressive symptoms, and lower quality of life [64, 71, 74]. In contrast, caregivers with greater self-competency and sense of meaning, may have a more stable mental status despite increased caregiving hours [75].

Interpersonal factors

Since informal caregiving is a dyadic process, the relationship between caregiver and cancer patient is an essential determinant for caregiving outcomes. Being a spousal caregiver is associated with greater psychosocial and financial unmet needs and higher distress [76, 77]. Spousal caregivers with higher marital satisfaction usually have better mental well-being when providing care to the patient [78, 79]. However, an insecure attachment between spousal caregiver and patient may prevent them from using common dyadic coping, and result in impaired quality of life [80]. Lack of effective communication regarding cancer- and caregiving-related concerns was found to be common between caregivers and cancer patients [36, 81, 82]. This is a significant predictor for depressive symptoms in caregivers during caregiving and after the death of the patient [83].

The functional performance of the patient and the demands of care have significant impact on caregiver burden and quality of life [84, 85]. Younger age of cancer patients was found to be associated with greater personal strain and depressive symptoms in caregivers [9••, 86]. In addition to caring for cancer patients, the presence of more dependent young children in the family needing to be cared for also predicts higher burden and distress in caregivers [87].

Cumulative evidence has shown that social support from friends and other family members predicts lower caregiver burden and better physical and mental health [60, 63•]. This may be attributed to the reinforcement of resilience of caregivers by social support [88]. Spousal support and family functioning are important determinants of financial burden and stress-related symptoms in parents of pediatric patients with cancer [89, 90]. Quality of life of caregivers was found to be associated with posttraumatic stress symptoms in childhood cancer survivors, and this relationship was mediated by posttraumatic stress symptoms of caregivers [91].

Institutional factors

The schedule of health care service was identified as a significant institutional factor. In recent qualitative studies, caregivers expressed that they felt distressed if professional support was not available in time for managing the deterioration of the patient [11••, 92]. Poorly organized home care services caused a sense of insecurity in caregivers [92]. Long waiting times and lack of a comfortable environment during clinic visits can amplify unpleasant caregiver emotions [93].

Lack of attention and communication regarding the well-being of caregivers from health care teams is another important institutional factor that should be considered. Several caregivers considered that health professionals focused entirely on patients and ignored their concerns [34]. They might become angry if realistic information on the prognosis of the patient was not provided by the health care team [55]. On the contrary, effective communication between caregivers and health professionals can improve the experience of caregivers end-of-life care for cancer patients and reduce decision regret [94].

Community factors

Inconvenient transportation and unbalanced geographical distribution of medical resources in the community are barriers for obtaining professional and non-professional support, which would increase burden and sense of insecurity [11••, 92, 95]. Financial and instrumental support from non-governmental organizations in the community (e.g., churches, charities, and philanthropies) can partially alleviate economic burden and practical issues of caregivers [11••, 96, 97].

Policy and environmental factors

Governments of high-income countries such as Australia [97, 98], Canada [96, 99], and Norway [92] can provide financial compensation for informal caregiving, that can attenuate the financial difficulties of cancer patients and caregivers. However, caregivers may experience undesired anxiety or insecurity if an application for governmental compensation is cumbersome and slowly processed [92]. Caregivers in low-income countries usually face financial and resource constrains due to the lack of support from the government [11••, 23, 100].

The recent coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has placed an additional burden on caregivers. COVID-19 can increase the concerns of caregivers about ongoing treatment and care for the patient [101, 102]. Nevertheless, some parents of childhood cancer survivors considered that the isolation experience during active anticancer treatment allowed them to better respond to the epidemic [103]. Several caregivers worried that the COVID-19 epidemic might affect psychosocial well-being of the patient [101, 104]. Furthermore, the “lockdown” and isolation in response to the COVID-19 epidemic can also affect social support and income [101, 103]. This can result in negative emotions such as loneliness, uncertainty, anxiety, and fear [102]. Numerous caregivers expressed a stronger sense of responsibility for the patient [102] and attached importance to efforts by the government and health professionals to support them [102, 103].

Innovations in outcome measurements for informal cancer caregivers

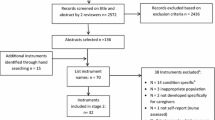

Literature reviews [105–106, 107••] have summarized commonly used assessment tools specific to informal cancer caregivers, which can help health professionals and researchers gain a comprehensive understanding of unmet needs and quality of life of caregivers regarding daily activity, health care services, information, personal well-being, employment and social security, communication, family support, and financial issues (Table 1). More recently, an array of new outcome measurements [108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116] have been developed for assessing the expanding domains of unmet needs, burden, quality of life, and associated factors in caregivers (Table 1). However, these instruments are still in the stage of preliminary testing and require further verification in larger and more diverse populations.

Innovations in interventions for supporting informal cancer caregivers

Two evidence-based reviews, analyzing a total of 79 randomized controlled trials published between 1983 and 2016, classified supportive interventions for informal cancer caregivers into three categories: psychoeducation, skills training, and therapeutic counseling [117, 118]. These interventions are mainly composed of multiple components covering patient care, family reintegration, and caregiver self-management [117, 118]. The target population of the interventions can be either caregivers per se or, more frequently, caregiver-patient dyads [117, 118]. Alam et al. suggested that the provision of palliative care to both patients and caregivers simultaneously should be considered as the disease and functional status of a cancer patient is closely related to the distress of the caregiver [9••]. Although pooled analysis of supportive interventions indicated significant improvement in caregiver burden, information needs, coping strategies, physical functioning, psychological well-being, and quality of life, the effects were mostly small and short-term [117, 119•]. Moreover, there were discordant findings across the individual randomized controlled trials.

In their scoping review, Samuelsson et al. summarized current supportive care models for informal cancer caregivers and concluded that the high heterogeneity in cancer diagnosis, disease trajectory, and intervention components are key factors that contributed to the inconclusive results of most studies [120••]. A few recent studies tried to address these issues. For instance, in a randomized controlled trial, El-Jawahri and colleagues tested a 6-session psychological intervention (BMT-CARE) in caregivers of patients with hematological malignancies throughout the trajectory of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. The results showed that, compared with those allocated in the usual care group (n = 45), the caregivers in the BMT-CARE group (n = 42) achieved statistically significant improvements in all the caregiver-reported outcomes including quality of life, self-efficacy, coping skills, caregiver burden, anxiety, and depression with moderate to large effect size [121].

Previous studies were conducted predominantly with white populations in Western countries, while other ethnic groups have typically been underrepresented. More recent work has attempted to address this issue. For example, a randomized controlled trial of a psychosocial intervention conducted by Badger et al. focused on Latino women with breast cancer and the caregivers and employed a bilingual intervention provider to comply with the language preference of the participants [122]. Another pilot trial used a racially diverse recruitment team to facilitate the recruitment of racially diverse research participants and successfully promoted the participation of African Americans in the study [123].

With the development of information technology, the provision of supportive interventions for caregivers has gradually shifted from a face-to-face format to telehealth, electronic health (eHealth), or mobile health (mHealth) formats. Previous literature reviews have shown that adopting technology-mediated interventions to facilitate convenient access to supportive resources is feasible, useable, and acceptable, and that these can improve the interaction between caregivers and the health care team, shared decision making, personal well-being, social support, and dyadic communication and relationship with cancer patients [124–125, 126•]. This is especially crucial for caregivers and cancer patients who have transportation difficulties. A randomized controlled trial demonstrated that a videoconference intervention can significantly relieve distress and anxiety of caregivers, who would otherwise need more than an hour to travel to the residence of the patient [127]. Under the current circumstance of the COVID-19 pandemic, remote supportive interventions may be more suitable for caregivers and patients [127]. However, the optimal content and amount of technology-mediated supportive interventions for caregivers needs to be further determined in future research. Another concern is the digital divide (i.e., the inequities in access to technology) in older adults, minority groups, and residents of low- and middle-income countries, which is regarded as an important barrier impeding implementation of technology-mediated supportive interventions [126•].

Knowledge translation and evidence implementation

The existing supportive interventions for informal cancer caregivers are mostly in the clinical trial stage and implementing these interventions into practice is difficult. By interviewing experts and potential end users of supportive cancer care, Ratcliff and colleagues identified that the essential factors hindering the implementation of research evidence into practice include deviations between the investigated intervention and caregiver/patient needs, lack of well-trained interdisciplinary teams, insufficient funding and time for supportive care provision, and exclusion of caregivers from current health care systems [128••].

To address these barriers, Campbell and colleagues lunched a quality improvement program with a designated interdisciplinary team to improve family caregiver identification, documentation, assessment, and needs-based intervention in a tertiary gynecologic oncology clinic. The program managed to increase family caregiver identification and assessment rates from 19% and 28% at baseline to 57% and 60% after eight PDSA (Plan-Do-Study-Act) cycles, respectively, with half of the identified caregivers having received the supportive intervention [129]. Bitz and colleagues shared their experience of integrating a couples-based interdisciplinary supportive care program into the standard of care. Based on the Values-Benefits-Outcomes Model of Engagement, this project has currently served nearly 2000 breast cancer patients and/or their partners and achieved high satisfaction rate among its users [130]. However, the two reports neither evaluated caregivers/patient quality of life and utilization of health care services, nor provided information on cost and cost-effectiveness.

Conclusion and future directions

Informal caregivers spend a large amount of time and energy in caring for cancer patients at the cost of their own health and well-being. Their contributions fill the gaps of cancer care discontinuity in the formal health care system, and this should be fully acknowledged. Understanding the distress and related social-ecological factors that caring brings and providing proactive and cost-effective supportive interventions to carers are important practice areas. Research evidence suggests that providing psychoeducation, skills training, and therapeutic counseling for caregivers or caregiver-patient dyads can be beneficial. In order to translate current research evidence into routine practice, further research needs to be undertaken. Suggestions for future practice changes and research are shown in Box 1.

Box 1 Suggestions for future practice and research

• Interventions should be designed based on both the real-word needs of caregivers and the practice context. • When formulating implementation schemes of a supportive intervention, it would be necessary to consider the social-ecological factors that may influence the outcomes and to address modifiable factors. • Emphasize interdisciplinary collaboration in practice and research to promote intervention provision and evidence dissemination. • Make full use of new technologies to ensure the cost-effectiveness, sustainability, and equity of the supportive interventions. • It would be valuable to explore how and why the different supportive interventions work or do not work in caregivers by using realist evaluation theory on the context-mechanism-outcome (CMO) configurations since they are complex interventions. • Given supportive interventions were found to have a delayed effect on several outcomes in caregivers [117], real-world studies with longer-term follow-up may be able to obtain richer information for decision-making. • Development of theories specific to guide research and evidence implementation in supporting caregivers is necessary. • Involve caregivers more in the health care discussions and decision-making, with the permission of the patient, and discuss with caregivers their experiences and challenges. • Have a referral and support system in place for caregivers that can be easily accessible with few hurdles. • Address caregiver issues of lack of practical skills, psychophysiological burden, economic support, and work discrimination at both the health care system level and policy level. |

Data availability

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Sung H, Farley J, Siegel RL, Haversine M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660.

Miller KD, Nogueira L, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH, Yabroff KR, Alfano CM, Jemal A, Kramer JL, Siegel RL. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(5):363–85. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21565.

Given CW. Family caregiving for cancer patients: the state of the literature and a direction for research to link the informal and formal care systems to improve quality and outcomes. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2019;35(4):389–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2019.06.014.

•• Sun V, Raz DJ, Kim JY. Caring for the informal cancer caregiver. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2019;13(3):238–42. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPC.0000000000000438. This reference is of major importance because it reviews technology-mediated interventions, informal caregiver issues, and guidelines to inform research and practice in supporting informal cancer caregivers.

Coumoundouros C, Ould Brahim L, Lambert SD, McCusker J. The direct and indirect financial costs of informal cancer care: a scoping review. Health Soc Care Community. 2019;27(5):e622–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12808.

Litzelman K, Blanch-Hartigan D, Lin CC, Han X. Correlates of the positive psychological byproducts of cancer: role of family caregivers and informational support. Palliat Support Care. 2017;15(6):693–703. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951517000050.

Fujinami R, Sun V, Zachariah F, Uman G, Grant M, Ferrell B. Family caregivers’ distress levels related to quality of life, burden, and preparedness. Psychooncology. 2015;24(1):54–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3562.

Alfano CM, Leach CR, Smith TG, Miller KD, Alcaraz KI, Cannady RS, Wender RC, Brawley OW. Equitably improving outcomes for cancer survivors and supporting caregivers: a blueprint for care delivery, research, education, and policy. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(1):35–49. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21548.

•• Alam S, Hannon B, Zimmermann C. Palliative care for family caregivers. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(9):926–36. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.19.00018. This reference is of major importance because it summarizes critical evidence regarding informal caregiving outcomes, risk factors, and interventions and proposes a CARES framework for supporting informal cancer caregivers.

Washington KT, Craig KW, Parker Oliver D, Ruggeri JS, Brunk SR, Goldstein AK, Demiris G. Family caregivers’ perspectives on communication with cancer care providers. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2019;37(6):777–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347332.2019.1624674.

•• Adejoh SO, Boele F, Akeju D, Dandadzi A, Nabirye E, Namisango E, Namukwaya E, Ebenso B, Nkhoma K, Allsop MJ. The role, impact, and support of informal caregivers in the delivery of palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a multi-country qualitative study. Palliat Med. 2021;35(3):552–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216320974925. This reference is of major importance because it provides deeper understanding of the multiple and complex roles played by informal cancer caregivers particularly in low- and middle-income countries and illustrated the impact exerted by caregiving and contextual factors on them.

• Veenstra CM, Wallner LP, Abrahamse PH, Janz NK, Katz SJ, Hawley ST. Understanding the engagement of key decision support persons in patient decision making around breast cancer treatment. Cancer. 2019;125(10):1709–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.31956. This reference is of importance because this population-based study creatively examines the engagement of informal decision supporters in the decision-making process of breast cancer patients as well as its value in achieving better subjective decision quality.

Dionne-Odom JN, Ejem D, Wells R, Barnato AE, Taylor RA, Rocque GB, Turkman YE, Kenny M, Ivankova NV, Bakitas MA, et al. How family caregivers of persons with advanced cancer assist with upstream healthcare decision-making: a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2019;14(3):e0212967. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212967.

Gao L, Liu JE, Zhou XP, Su YL, Wang PL. Supporting her as the situation changes: a qualitative study of spousal support strategies for patients with breast cancer in China. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2020;29(1):e13176. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.13176.

Chittem M, Norman P, Harris P. Primary family caregivers’ reasons for disclosing versus not disclosing a cancer diagnosis in India. Cancer Nurs. 2020;43(2):126–33. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000669.

Kebede BG, Abraha A, Andersson R, Munthe C, Linderholm M, Linderholm B, Berbyuk LN. Communicative challenges among physicians, patients, and family caregivers in cancer care: an exploratory qualitative study in Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2020;15(3):e0230309. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0230309.

Malhotra C, Kanesvaran R, Barr Kumarakulasinghe N, Tan SH, Xiang L, Tulsky JA, Pollak KI. Oncologist-patient-caregiver decision-making discussions in the context of advanced cancer in an Asian setting. Health Expect. 2020;23(1):220–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12994.

Gage-Bouchard EA, LaValley S, Devonish JA. Deciphering the signal from the noise: caregivers’ information appraisal and credibility assessment of cancer-related information exchanged on social networking sites. Cancer Control. 2019;26(1):1073274819841609. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073274819841609.

Hart RI, Cameron DA, Cowie FJ, Harden J, Heaney NB, Rankin D, Jesudason AB, Lawton J. The challenges of making informed decisions about treatment and trial participation following a cancer diagnosis: a qualitative study involving adolescents and young adults with cancer and their caregivers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4851-1.

Jepsen LO, Friis LS, Hansen DG, Marcher CW, Hoybye MT. Living with outpatient management as spouse to intensively treated acute leukemia patients. PLoS One. 2019;14(5):e0216821. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216821.

Schwartz K, Beebe-Dimmer J, Hastert TA, Ruterbusch JJ, Mantey J, Harper F, Thompson H, Pandolfi S, Schwartz AG. Caregiving burden among informal caregivers of African American cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2021;15(4):630–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-020-00956-x.

Kizza IB, Maritz J. Family caregivers for adult cancer patients: knowledge and self-efficacy for pain management in a resource-limited setting. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(6):2265–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4504-7.

Salifu Y, Almack K, Caswell G. ‘My wife is my doctor at home’: a qualitative study exploring the challenges of home-based palliative care in a resource-poor setting. Palliat Med. 2021;35(1):97–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216320951107.

Pare-Blagoev EJ, Ruble K, Bryant C, Jacobson L. Schooling in survivorship: understanding caregiver challenges when survivors return to school. Psychooncology. 2019;28(4):847–53. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5026.

Veenstra CM, Acosta J, Sharar R, Hawley ST, Morris AM. Partners’ engagement in surveillance among survivors of colorectal cancer: a qualitative study. Cancer Med. 2021;10(4):1289–96. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.3725.

Pottle J, Hiscock J, Neal RD, Poolman M. Dying at home of cancer: whose needs are being met? The experience of family carers and healthcare professionals (a multiperspective qualitative study). BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2020;10(1):e6. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2016-001145.

Bloom RD, Beck S, Chou WS, Reblin M, Ellington L. In their own words: experiences of caregivers of adults with cancer as expressed on social media. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2019;46(5):617–30. https://doi.org/10.1188/19.ONF.617-630.

Abbasi A, Mirhosseini S, Basirinezhad MH, Ebrahimi H. Relationship between caring burden and quality of life in caregivers of cancer patients in Iran. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(9):4123–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-05240-y.

Ketcher D, Reblin M. Social networks of caregivers of patients with primary malignant brain tumor. Psychol Health Med. 2019;24(10):1235–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2019.1619787.

Ullrich A, Marx G, Bergelt C, Benze G, Zhang Y, Wowretzko F, Heine J, Dickel LM, Nauck F, Bokemeyer C, et al. Supportive care needs and service use during palliative care in family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer: a prospective longitudinal study. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(3):1303–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05565-z.

Wang T, Molassiotis A, Tan JY, Chung BPM, Huang HQ. Prevalence and correlates of unmet palliative care needs in dyads of Chinese patients with advanced cancer and their informal caregivers: a cross-sectional survey. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(3):1683–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05657-w.

Chua GP, Pang GSY, Yee ACP, Neo PSH, Zhou S, Lim C, Wong YY, Qu DL, Pan FT, Yang GM. Supporting the patients with advanced cancer and their family caregivers: what are their palliative care needs? BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):768. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-020-07239-9.

Wang T, Molassiotis A, Chung BPM, Zheng SL, Huang HQ, Tan JB. A qualitative exploration of the unmet information needs of Chinese advanced cancer patients and their informal caregivers. BMC Palliat Care. 2021;20(1):83. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-021-00774-7.

Oldertroen Solli K, de Boer M, Nyheim Solbraekke K, Thoresen L. Male partners’ experiences of caregiving for women with cervical cancer-a qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28(5-6):987–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14688.

Albers LF, Van Ek GF, Krouwel EM, Oosterkamp-Borgelink CM, Liefers GJ, Den Ouden MEM, Den Oudsten BL, Krol-Warmerdam EEM, Guicherit OR, Linthorst-Niers E, et al. Sexual health needs: how do breast cancer patients and their partners want information? J Sex Marital Ther. 2020;46(3):205–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2019.1676853.

Hawkey A, Ussher JM, Perz J, Parton C. Talking but not always understanding: couple communication about infertility concerns after cancer. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):161. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10188-y.

Teixeira RJ, Remondes-Costa S, Graca Pereira M, Brandao T. The impact of informal cancer caregiving: a literature review on psychophysiological studies. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2019;28(4):e13042. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.13042.

Luckett T, Agar M, DiGiacomo M, Lam L, Phillips J. Health status in South Australians caring for people with cancer: a population-based study. Psychooncology. 2019;28(11):2149–56. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5200.

Abdullah NN, Idris IB, Shamsuddin K, Abdullah NMA. Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) of gastrointestinal cancer caregivers: the impact of caregiving. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2019;20(4):1191–7. https://doi.org/10.31557/APJCP.2019.20.4.1191.

Webber K, Davies AN, Leach C, Bradley A. Alcohol and drug use disorders in patients with cancer and caregivers: effects on caregiver burden. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2020;10(2):242-247. http://dx.doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2019-002127

Cho IY, Chung NG, Baek HJ, Lee JW, Sung KW, Shin DW, Yoo JE, Song YM. Health behaviors of caregivers of childhood cancer survivors: a cross-sectional study. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):296. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-020-06765-w.

Steel JL, Cheng H, Pathak R, Wang Y, Miceli J, Hecht CL, Haggerty D, Peddada S, Geller DA, Marsh W, et al. Psychosocial and behavioral pathways of metabolic syndrome in cancer caregivers. Psychooncology. 2019;28(8):1735–42. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5147.

Buck HG, Benitez B, Fradley MG, Donovan KA, McMillan SC, Reich RR, Wang HL. Examining the relationship between patient fatigue-related symptom clusters and carer depressive symptoms in advanced cancer dyads: a secondary analysis of a large hospice data set. Cancer Nurs. 2020;43(6):498–505. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000737.

An Y, Fu G, Yuan G. Quality of life in patients with breast cancer: the influence of family caregiver’s burden and the mediation of patient’s anxiety and depression. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2019;207(11):921–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000001040.

Hou WK, Liang L, Lau KM, Hall M. Savouring and psychological well-being in family dyads coping with cancer: an actor-partner interdependence model. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2019;28(4):e13047. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.13047.

Palacio C, Limonero JT. The relationship between the positive aspects of caring and the personal growth of caregivers of patients with advanced oncological illness: postraumattic growth and caregiver. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(7):3007–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-05139-8.

de Camargos MG, Paiva BSR, de Oliveira MA, de Souza FP, de Almeida VTN, de Andrade CS, de Almeida CSL, Paiva CE. An explorative analysis of the differences in levels of happiness between cancer patients, informal caregivers and the general population. BMC Palliat Care. 2020;19(1):106. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-020-00594-1.

Takeuchi E, Kim Y, Shaffer KM, Cannady RS, Carver CS. Fear of cancer recurrence promotes cancer screening behaviors among family caregivers of cancer survivors. Cancer. 2020;126(8):1784–92. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.32701.

Langenberg S, van Herpen CML, van Opstal CCM, Wymenga ANM, van der Graaf WTA, Prins JB. Caregivers’ burden and fatigue during and after patients’ treatment with concomitant chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced head and neck cancer: a prospective, observational pilot study. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(11):4145–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04700-9.

• Ream E, Richardson A, Lucas G, Marcu A, Foster R, Fuller G, Oakley C. Understanding the support needs of family members of people undergoing chemotherapy: a longitudinal qualitative study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2021;50:101861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2020.101861. This reference is of importance because it provides unique insight into the evolution of family caregivers’ experience, needs, and confidence in supporting the patient throughout the course of chemotherapy by using a longitudinal qualitative research method.

• Sato T, Fujisawa D, Arai D, Nakachi I, Takeuchi M, Nukaga S, Kobayashi K, Ikemura S, Terai H, Yasuda H, et al. Trends of concerns from diagnosis in patients with advanced lung cancer and their family caregivers: a 2-year longitudinal study. Palliat Med. 2021;35(5):943–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/02692163211001721. This reference is of importance because it depicts the characteristics of long-term needs and concerns in cancer patients and their informal caregivers by analyzing real-world longitudinal data.

Garcia-Torres F, Jablonski MJ, Gomez Solis A, Jaen-Moreno MJ, Galvez-Lara M, Moriana JA, Moreno-Diaz MJ, Aranda E. Caregiver burden domains and their relationship with anxiety and depression in the first six months of cancer diagnosis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(11):4101. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17114101.

Duckworth KE, McQuellon RP, Russell GB, Perry KC, Nightingale C, Shen P, Votanopoulos KI, Morris B, Levine EA. Caregiver quality of life before and after cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. J Am Coll Surg. 2020;230(4):679–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2019.12.020.

Ross A, Perez A, Wehrlen L, Lee LJ, Yang L, Cox R, Bevans M, Ding A, Wiener L, Wallen GR. Factors influencing loneliness in cancer caregivers: a longitudinal study. Psychooncology. 2020;29(11):1794–801. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5477.

Rodenbach RA, Norton SA, Wittink MN, Mohile S, Prigerson HG, Duberstein PR, Epstein RM. When chemotherapy fails: emotionally charged experiences faced by family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(5):909–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2018.12.014.

Norton SA, Wittink MN, Duberstein PR, Prigerson HG, Stanek S, Epstein RM. Family caregiver descriptions of stopping chemotherapy and end-of-life transitions. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(2):669–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4365-0.

Hisamatsu M, Shinchi H, Tsutsumi Y. Experiences of spouses of patients with cancer from the notification of palliative chemotherapy discontinuation to bereavement: a qualitative study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2020;45:101721. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2020.101721.

Oechsle K, Ullrich A, Marx G, Benze G, Wowretzko F, Zhang Y, Dickel LM, Heine J, Wendt KN, Nauck F, et al. Prevalence and predictors of distress, anxiety, depression, and quality of life in bereaved family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2020;37(3):201–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909119872755.

Tsai WI, Wen FH, Kuo SC, Prigerson HG, Chou WC, Shen WC, Tang ST. Symptoms of prolonged grief and major depressive disorders: distinctiveness and temporal relationship in the first 2 years of bereavement for family caregivers of terminally ill cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2020;29(4):751–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5333.

Cochrane A, Reid O, Woods S, Gallagher P, Dunne S. Variables associated with distress amongst informal caregivers of people with lung cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Psychooncology. 2021;30(8):1246–61. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5694.

Lichtenthal WG, Roberts KE, Catarozoli C, Schofield E, Holland JM, Fogarty JJ, Coats TC, Barakat LP, Baker JN, Brinkman TM, et al. Regret and unfinished business in parents bereaved by cancer: a mixed methods study. Palliat Med. 2020;34(3):367–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216319900301.

McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(4):351–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019818801500401.

• Ochoa CY, Buchanan Lunsford N, Lee SJ. Impact of informal cancer caregiving across the cancer experience: a systematic literature review of quality of life. Palliat Support Care. 2020;18(2):220–40. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951519000622. This reference is of importance because it summarizes and synthesizes existing literature regarding the impact of cancer caregiving on informal caregivers’ quality of life throughout the illness trajectory of cancer.

Yeung NCY, Ji L, Zhang Y, Lu G, Lu Q. Caregiving burden and self-efficacy mediate the association between individual characteristics and depressive symptoms among husbands of Chinese breast cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(7):3125–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-05102-7.

Mollica MA, Smith AW, Kent EE. Caregiving tasks and unmet supportive care needs of family caregivers: a U.S. population-based study. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103(3):626–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2019.10.015.

Stolz-Baskett P, Taylor C, Glaus A, Ream E. Supporting older adults with chemotherapy treatment: a mixed methods exploration of cancer caregivers’ experiences and outcomes. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2021;50:101877. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2020.101877.

Spatuzzi R, Giulietti MV, Ricciuti M, Merico F, Romito F, Reggiardo G, Birgolotti L, Fabbietti P, Raucci L, Rosati G, et al. Does family caregiver burden differ between elderly and younger caregivers in supporting dying patients with cancer? An Italian study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2020;37(8):576–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909119890840.

Borstelmann NA, Rosenberg S, Gelber S, Zheng Y, Meyer M, Ruddy KJ, Schapira L, Come S, Borges V, Cadet T, et al. Partners of young breast cancer survivors: a cross-sectional evaluation of psychosocial concerns, coping, and mental health. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2020;38(6):670–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347332.2020.1823546.

Hastert TA, Ruterbusch JJ, Nair M, Noor MI, Beebe-Dimmer JL, Schwartz K, Baird TE, Harper FWK, Thompson H, Schwartz AG. Employment outcomes, financial burden, anxiety, and depression among caregivers of African American cancer survivors. JCO Oncol Pract. 2020;16(3):e221–33. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.19.00410.

Xu H, Kadambi S, Mohile SG, Yang S, Kehoe LA, Wells M, Culakova E, Kamen C, Obrecht S, Mohamed M, et al. Caregiving burden of informal caregivers of older adults with advanced cancer: the effects of rurality and education. J Geriatr Oncol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2021.04.002.

Uzar-Ozceti NY, Dursun SI. Quality of life, caregiver burden, and resilience among the family caregivers of cancer survivors. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2020;48:101832. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2020.101832.

Miller LM, Utz RL, Supiano K, Lund D, Caserta MS. Health profiles of spouse caregivers: the role of active coping and the risk for developing prolonged grief symptoms. Soc Sci Med. 2020;266:113455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113455.

Kuo SC, Wen FH, Chen JS, Chou WC, Shen WC, Tang ST. Preloss psychosocial resources predict depressive symptom trajectories among terminally ill cancer patients’ caregivers in their first two years of bereavement. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2019;58(1):29–38 e22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.04.003.

Ketcher D, Otto AK, Reblin M. Caregivers of patients with brain metastases: a description of caregiving responsibilities and psychosocial well-being. J Neurosci Nurs. 2020;52(3):112–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/JNN.0000000000000500.

Teo I, Baid D, Ozdemir S, Malhotra C, Singh R, Harding R, Malhotra R, Yang MG, Neo SH, Cheung YB, et al. Family caregivers of advanced cancer patients: self-perceived competency and meaning-making. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2020;10(4):435–42. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2019-001979.

Ting A, Lucette A, Carver CS, Cannady RS, Kim Y. Preloss spirituality predicts postloss distress of bereaved cancer caregivers. Ann Behav Med. 2019;53(2):150–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/abm/kay024.

Kim Y, Carver CS. Unmet needs of family cancer caregivers predict quality of life in long-term cancer survivorship. J Cancer Surviv. 2019;13(5):749–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-019-00794-6.

Chien CH, Chuang CK, Liu KL, Pang ST, Wu CT, Chang YH. Prostate cancer-specific anxiety and the resulting health-related quality of life in couples. J Adv Nurs. 2019;75(1):63–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13828.

Min J, Yorgason JB, Fast J, Chudyk A. The impact of spouse’s illness on depressive symptoms: the roles of spousal caregiving and marital satisfaction. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2020;75(7):1548–57. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbz017.

Crangle CJ, Torbit LA, Ferguson SE, Hart TL. Dyadic coping mediates the effects of attachment on quality of life among couples facing ovarian cancer. J Behav Med. 2020;43(4):564–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-019-00096-3.

Martinez YC, Ellington L, Vadaparampil ST, Heyman RE, Reblin M. Concordance of cancer related concerns among advanced cancer patient-spouse caregiver dyads. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2020;38(2):143–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347332.2019.1642285.

Siminoff LA, Wilson-Genderson M, Barta S, Thomson MD. Hematological cancer patient-caregiver dyadic communication: a longitudinal examination of cancer communication concordance. Psychooncology. 2020;29(10):1571–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5458.

Bachner YG, Guldin MB, Nielsen MK. Mortality communication and post-bereavement depression among Danish family caregivers of terminal cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(4):1951–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05685-6.

Duimering A, Turner J, Chu K, Huang F, Severin D, Ghosh S, Yee D, Wiebe E, Usmani N, Gabos Z, et al. Informal caregiver quality of life in a palliative oncology population. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(4):1695–702. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04970-3.

Franchini L, Ercolani G, Ostan R, Raccichini M, Samolsky-Dekel A, Malerba MB, Melis A, Varani S, Pannuti R. Caregivers in home palliative care: gender, psychological aspects, and patient’s functional status as main predictors for their quality of life. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(7):3227–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-05155-8.

Chardon ML, Canter KS, Pai ALH, Peugh JL, Madan-Swain A, Vega G, Joffe NE, Kazak AE. The impact of pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplant timing and psychosocial factors on family and caregiver adjustment. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67(11):e28552. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.28552.

Jablonski MJ, Garcia-Torres F, Zielinska P, Bulat A, Brandys P. Emotional burden and perceived social support in male partners of women with cancer. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(12):4188. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124188.

Chen SC, Huang BS, Hung TM, Lin CY, Chang YL, Chung CF. Factors associated with resilience among primary caregivers of patients with advanced cancer within the first 6 months post-treatment in Taiwan: a cross-sectional study. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2020;52(5):488–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12582.

Lemos MS, Lima L, Silva C, Fontoura S. Disease-related parenting stress in the post-treatment phase of pediatric cancer. Compr Child Adolesc Nurs. 2020;43(1):65–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694193.2019.1570393.

Santacroce SJ, Kneipp SM. Influence of pediatric cancer-related financial burden on parent distress and other stress-related symptoms. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67(3):e28093. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.28093.

de Castro EK, Crespo C, Barros L, Armiliato MJ, Gregianin L. Assessing the relationship between PTSS in childhood cancer survivors and their caregivers and their quality of life. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2021;38(2):147–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/08880018.2020.1825574.

Barlund AS, Andre B, Sand K, Brenne AT. A qualitative study of bereaved family caregivers: feeling of security, facilitators and barriers for rural home care and death for persons with advanced cancer. BMC Palliat Care. 2021;20(1):7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-020-00705-y.

Mueller EL, Cochrane AR, Moore CM, Jenkins KB, Bauer NS, Wiehe SE. Assessing needs and experiences of preparing for medical emergencies among children with cancer and their caregivers. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2020;42(8):e723–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPH.0000000000001826.

An AW, Ladwig S, Epstein RM, Prigerson HG, Duberstein PR. The impact of the caregiver-oncologist relationship on caregiver experiences of end-of-life care and bereavement outcomes. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(9):4219–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-05185-2.

Mallya S, Daniels M, Kanter C, Stone A, Cipolla A, Edelstein K, D’Agostino N. A qualitative analysis of the benefits and barriers of support groups for patients with brain tumours and their caregivers. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(6):2659–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-05069-5.

Tsimicalis A, Stevens B, Ungar WJ, Castro A, Greenberg M, Barr R. Shifting priorities for the survival of my child: managing expenses, increasing debt, and tapping into available resources to maintain the financial stability of the family. Cancer Nurs. 2020;43(2):147–57. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000698.

Kelada L, Wakefield CE, Vetsch J, Schofield D, Sansom-Daly UM, Hetherington K, O’Brien T, Cohn RJ, Anazodo A, Viney R, et al. Financial toxicity of childhood cancer and changes to parents’ employment after treatment completion. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67(7):e28345. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.28345.

Warby A, Dhillon HM, Kao S, Vardy JL. A survey of patient and caregiver experience with malignant pleural mesothelioma. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(12):4675–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04760-x.

Humphries B, Lauzier S, Drolet M, Coyle D, Masse B, Provencher L, Robidoux A, Maunsell E. Wage losses among spouses of women with nonmetastatic breast cancer. Cancer. 2020;126(5):1124–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.32638.

Boamah Mensah AB, Adamu B, Mensah KB, Dzomeku VM, Agbadi P, Kusi G, Apiribu F. Exploring the social stressors and resources of husbands of women diagnosed with advanced breast cancer in their role as primary caregivers in Kumasi, Ghana. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(5):2335–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05716-2.

Darlington AE, Morgan JE, Wagland R, Sodergren SC, Culliford D, Gamble A, Phillips B. COVID-19 and children with cancer: parents’ experiences, anxieties and support needs. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2021;68(2):e28790. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.28790.

Chia JMX, Goh ZZS, Chua ZY, Ng KYY, Ishak D, Fung SM, Ngeow JYY, Griva K. Managing cancer in context of pandemic: a qualitative study to explore the emotional and behavioural responses of patients with cancer and their caregivers to COVID-19. BMJ Open. 2021;11(1):e041070. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041070.

Wimberly CE, Towry L, Caudill C, Johnston EE, Walsh KM. Impacts of COVID-19 on caregivers of childhood cancer survivors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2021;68(4):e28943. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.28943.

Ng KYY, Zhou S, Tan SH, Ishak NDB, Goh ZZS, Chua ZY, Chia JMX, Chew EL, Shwe T, Mok JKY, et al. Understanding the psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on patients with cancer, their caregivers, and health care workers in Singapore. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020;6:1494–509. https://doi.org/10.1200/GO.20.00374.

Prue G, Santin O, Porter S. Assessing the needs of informal caregivers to cancer survivors: a review of the instruments. Psychooncology. 2015;24(2):121–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3609.

Michels CT, Boulton M, Adams A, Wee B, Peters M. Psychometric properties of carer-reported outcome measures in palliative care: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2016;30(1):23–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216315601930.

•• Tanco K, Park JC, Cerana A, Sisson A, Sobti N, Bruera E. A systematic review of instruments assessing dimensions of distress among caregivers of adult and pediatric cancer patients. Palliat Support Care. 2017;15(1):110–24. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951516000079. This reference is of major importance as it examines best available literature regarding the instruments used for assessing burden, satisfaction with health care delivery, needs, quality of life, and other relevant issues in informal caregivers of adult and pediatric cancer patients.

Kim Y, Carver CS, Cannady RS. Bereaved family cancer caregivers’ unmet needs: measure development and validation. Ann Behav Med. 2020;54(3):164–75. https://doi.org/10.1093/abm/kaz036.

Kühnel MB, Ramsenthaler C, Bausewein C, Fegg M, Hodiamont F. Validation of two short versions of the Zarit Burden Interview in the palliative care setting: a questionnaire to assess the burden of informal caregivers. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(11):5185–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-05288-w.

Shilling V, Starkings R, Jenkins V, Cella D, Fallowfield L. Development and validation of the caregiver roles and responsibilities scale in cancer caregivers. Qual Life Res. 2019;28(6):1655–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-019-02154-4.

Cheung YB, Neo SHS, Teo I, Yang GM, Lee GL, Thumboo J, Chia JWK, Koh ARX, Qu DLM, Che WWL, et al. Development and evaluation of a quality of life measurement scale in English and Chinese for family caregivers of patients with advanced cancers. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2019;17(1):35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-019-1108-y.

Cheung YB, Neo SHS, Yang GM, Lee GL, Teo I, Koh ARX, Thumboo J, Wee HL. Two valid and reliable short forms of the Singapore caregiver quality of life scale were developed: SCQOLS-10 and SCQOLS-15. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;121:101–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.02.003.

Chernichky-Karcher S, Venetis MK, Lillie H. The Dyadic Communicative Resilience Scale (DCRS): scale development, reliability, and validity. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(12):4555–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04763-8.

Demiris G, Ganz FD, Han CJ, Pike K, Oliver DP, Washington K. Design and preliminary testing of the Caregiver-Centered Communication Questionnaire (CCCQ). J Palliat Care. 2020;35(3):154–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/0825859719887239.

Faccio F, Gandini S, Renzi C, Fioretti C, Crico C, Pravettoni G. Development and validation of the Family Resilience (FaRE) Questionnaire: an observational study in Italy. BMJ Open. 2019;9(6):e024670. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024670.

Pai ALH, Swain AM, Chen FF, Hwang WT, Vega G, Carlson O, Ortiz FA, Canter K, Joffe N, Kolb EA, et al. Screening for family psychosocial risk in pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with the Psychosocial Assessment Tool. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;25(7):1374–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2019.03.012.

Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Song L, Zhang L, Mood DW. Interventions with family caregivers of cancer patients: meta-analysis of randomized trials. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60(5):317–39. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.20081.

Ferrell B, Wittenberg E. A review of family caregiving intervention trials in oncology. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(4):318–25. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21396.

• Lee JZJ, Chen HC, Lee JX, Klainin-Yobas P. Effects of psychosocial interventions on psychological outcomes among caregivers of advanced cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06102-2. This reference is of importance because it synthesizes the best available evidence regarding the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions in informal caregivers of advanced cancer patients.

•• Samuelsson M, Wennick A, Jakobsson J, Bengtsson M. Models of support to family members during the trajectory of cancer: a scoping review. J Clin Nurs. 2021;30(21-22):3072–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15832. This reference is of major importance because it comprehensively maps the existing support models for informal cancer caregivers during the cancer trajectory.

El-Jawahri A, Jacobs JM, Nelson AM, Traeger L, Greer JA, Nicholson S, Waldman LP, Fenech AL, Jagielo AD, D’Alotto J, et al. Multimodal psychosocial intervention for family caregivers of patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a randomized clinical trial. Cancer. 2020;126(8):1758–65. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.32680.

Badger TA, Segrin C, Sikorskii A, Pasvogel A, Weihs K, Lopez AM, Chalasani P. Randomized controlled trial of supportive care interventions to manage psychological distress and symptoms in Latinas with breast cancer and their informal caregivers. Psychol Health. 2020;35(1):87–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2019.1626395.

Dionne-Odom JN, Wells RD, Guastaferro K, Azuero A, Hendricks BA, Currie ER, Bechthold A, Dosse C, Taylor R, Reed RD, et al. An early palliative care telehealth coaching intervention to enhance advanced cancer family caregivers’ decision support skills: the CASCADE pilot factorial trial. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2021;S0885-3924(21):00478–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.07.023.

Badr H, Carmack CL, Diefenbach MA. Psychosocial interventions for patients and caregivers in the age of new communication technologies: opportunities and challenges in cancer care. J Health Commun. 2015;20(3):328–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2014.965369.

Heynsbergh N, Heckel L, Botti M, Livingston PM. Feasibility, useability and acceptability of technology-based interventions for informal cancer carers: a systematic review. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):244. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4160-9.

• Luo X, Gao L, Li J, Lin Y, Zhao J, Li Q. A critical literature review of dyadic web-based interventions to support cancer patients and their caregivers, and directions for future research. Psychooncology. 2020;29(1):38–48. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5278. This reference is of importance because it critically analyzes existing evidence regarding web-based supportive interventions for cancer patient-caregiver dyad and provides recommendations for future research.

Douglas SL, Mazanec P, Lipson AR, Day K, Blackstone E, Bajor DL, Saltzman J, Krishnamurthi S. Videoconference intervention for distance caregivers of patients with cancer: a randomized controlled trial. JCO Oncol Pract. 2021;17(1):e26–35. https://doi.org/10.1200/OP.20.00576.

•• Ratcliff CG, Vinson CA, Milbury K, Badr H. Moving family interventions into the real world: what matters to oncology stakeholders? J Psychosoc Oncol. 2019;37(2):264–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347332.2018.1498426. This reference is of major importance because it demonstrates the barriers to integrating supportive interventions for informal cancer caregivers into clinical practice.

Campbell GB, Boisen MM, Hand LC, Lee YJ, Lersch N, Roberge MC, Suchonic B, Thomas TH, Donovan HS. Integrating family caregiver support into a gynecologic oncology practice: an ASCO quality training program project. JCO Oncol Pract. 2020;16(3):e264–70. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.19.00409.

Bitz C, Kent EE, Clark K, Loscalzo M. Couples coping with cancer together: successful implementation of a caregiver program as standard of care. Psychooncology. 2020;29(5):902–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5364.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Prof. Alex Molassiotis reports research grants from Helsinn, outside the submitted work. Mr. Mian Wang has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Palliative and Supportive Care

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Molassiotis, A., Wang, M. Understanding and Supporting Informal Cancer Caregivers. Curr. Treat. Options in Oncol. 23, 494–513 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11864-022-00955-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11864-022-00955-3