Abstract

Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) make a large class of biodegradable biopolymers that are naturally synthesized by numerous microorganisms. These biopolymers could be an alternative to commonly used plastics based on petroleum. Production of PHAs in bioreactors using microorganisms is not widely applied due to its unprofitability. Using transgenic plants for this purpose may be cheaper and more environmental friendly because the biosynthesis of PHAs in plants is based only on water, mineral salts, CO2 and light. Additionally, plants are not capable of degrading PHAs as bacteria do, and extraction of PHAs from plant tissues is not always necessary. The main objective of this work is a review of possibilities of PHA biosynthesis in transgenic plants and presentation of general information on properties and potential application possibilities of these biopolymers. The possibility of syntheses and accumulation of PHA in several transgenic plants has been studied for some years. Many experiments were performed on model plant Arabidopsis thaliana, however, the research has also revealed a great potential of transgenic crop plants such as camelina (Camelina sativa), tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) or sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum) as a good sources of PHAs. The highest level of PHAs accumulation in plants was achieved in transgenic A. thaliana (up to 40% of the dry weight of the leaf), and among crop plants in C. sativa (up to 20% of the dry weight of the seed). Increasing knowledge on PHAs permits expansion of the possibilities of these biopolymers use even at a low level of their accumulation in plant tissues.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

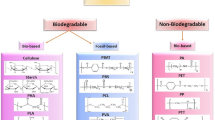

Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) are biodegradable biopolymers naturally synthesized and accumulated as intracellular energy and carbon reserves by a wide range of bacteria (ca. 300 species) (Sabbagh and Muhamad 2017; Kosseva and Rusbandi 2018). Production of PHAs in microbial cells is intensified under specific conditions such as the lack of nitrogen, phosphorus, sulfur, potassium, zinc, iron, magnesium or oxygen (Masood et al. 2014). PHAs are round shape granules with a diameter of 0.1–0.2 µm which are accumulated in the cytoplasm. PHAs polymers are made of identical monomers whose number ranges from 600 to 35,000. The chemical structure of an exemplary monomer is shown in Fig. 1. PHAs have properties similar to those of conventional petrochemical plastics. In addition, products made of these materials are natural, nontoxic, renewable and biocompatible, which make them more attractive than non-biodegradable petrochemical plastics (Sharma et al. 2016). Furthermore, it is supposed that the production of synthetic polymers will increase from 280 million tons in 2011 to even 810 million tons by 2050 (Gumel et al. 2013). For the above-mentioned reasons, from among other alternatives to petroleum-based plastics, PHAs have enjoyed great interest in the academia and industry. The differences in traits of a wide range of PHAs depend mainly on their monomers’ compositions. The first observed and most studied PHA is polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB). PHB is stiff and brittle, however, in the form of fibers behaves such as elastic material. One of the greatest advantages of PHB is air impermeability and water insolubility. It has a helical crystalline structure which seems to be a crucial feature that determines the possibility of the chemical and mechanical processing of the polymer. Furthermore, a non-toxic and thermoplastic nature of PHB makes it a very attractive material as a replacement for conventional plastics. Some physical properties of selected PHAs are shown in Table 1. Interestingly, some properties of PHAs are similar to those of conventional plastics such as polypropylene (Anjum et al. 2016). However, the whole process of bioplastic production is still more expensive than obtaining petrochemically based plastics products (Baikar et al. 2017). For the economic reasons, i.e., high costs of nutrient substrates for bacteria, PHAs mass scale production using microorganisms is not popular, which stimulates efforts aimed at reducing the cost of production of these compounds. One of the possibilities is to try to obtain transgenic plants that would be used as PHAs natural bioreactors. However, the greatest difficulty of biosynthesis of complex PHAs structures in plant cells is to control the appropriate ratio and composition of the monomers that are formed in them (Anderson et al. 2011). These attempts were successful in the 1990s when the Arabidopsis thaliana was transformed with genes encoding the enzymes needed for PHB biosynthesis, isolated from Alcaligenes eutrophus (Poirier et al. 1992).

Applications of polyhydroxyalkanoates

Physical and chemical properties of PHAs make them attractive for many applications. While the greatest focus is on the possibility of substituting hardly degradable plastics based on petroleum, new and interesting examples of their applications in industry, animal husbandry, crop cultivation and medicine are emerging. PHAs may be applicable to produce chemicals such as crotonic acid, n-butanol, acrylates, maleic anhydride or propylene (Snell et al. 2015). PHB can be used as an animal feed supplement which increases resistance to certain pathogens (Somleva et al. 2013). In addition, these polymers can be used in agriculture for encapsulating seeds, fertilizers and therapeutic drugs thus allowing slow and gradual release of active ingredients. PHAs may also be the basis for the production of biodegradable films used to protect young plants (Sharma et al. 2016).

Some PHAs can be used in medicine to produce implants. However, to play an important role in the field of medicine they must show biological compatibility, they must not be rejected and they should not cause an inflammatory reaction (Koller 2018). In addition, biopolymers replacing synthetic implants must be fully biodegradable after the relevant tissues have been regenerated. PHB, poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) (PHBV), poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-4-hydroxybutyrate) (P3HB4HB), poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) (PHBHHx), and poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) (PHBVHHx) are biomaterials that stimulate cell proliferation and tissue regeneration without inducing tumor growth. Experimental studies on rats, dogs and sheep have shown that both PHB and PHBV can act as a scaffolding to regenerating cells of the gastrointestinal tract and blood vessels (Masood et al. 2014). For the treatment of nervous system disorders, PHBVHHx appears to be the best of PHAs. It has been shown that stem cells differentiate into neurons of the highest efficiency in the three-dimensional structures of PHBVHHx nanofibers. In the near future, PHBVHHx may become salvative in treating the most difficult regenerating tissue that is a neuronal cell system (Wang et al. 2010). It has been found that some PHAs monomers, especially (R)-3-hydroxybutyrate (3HB), have therapeutic effects on people affected by Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s disease and osteoporosis (Chen 2009). In addition, PHAs show some potential for the application in pharmaceutical industry as anti-HIV drugs, anti-cancer drugs, antibiotics, etc. (Tan et al. 2014).

Examples of PHAs applications presented above, involve their extraction from microorganisms and plant tissues. It means that it is necessary to obtain a purified product that will become the raw material for various applications. However, some examples show that PHA isolation is not necessary, or even not recommended. One of them may be cotton-transgenic fibers, which are used to produce fabrics that meet desirable human traits. Such fibers with PHB inclusions are characterized by increased flexibility, strength and stiffness, as well as reduced heat absorption and water absorption. These improved features allow the use of modified cotton fibers to produce thermal clothing and insulation materials (John 1997).

Furthermore, similarly as for cotton, the genetic modifications introduced in flax are aimed at improving the quality and mechanical properties of the fiber. Under natural conditions, a number of polysaccharides such as cellulose, hemicellulose, pectin, and phenolic lignin polymers are included in flax fiber. The slight accumulation of PHB in flax stem cells has improved the elasticity and tensile strength of the fibers, which at the same time become more environmentally friendly by increasing their biodegradability. In addition, the material obtained from flax fibers containing PHB inclusions can be used in medicine to create special dressings for chronic wounds. Due to the significantly increased level of soluble phenolic compounds in modified flax that exhibit antioxidant properties, the range of biomedical use of the material made from such plants has been increasing. It has also been shown that linen dressings made of modified plant fibers favor the proliferation of human fibroblasts and have antibacterial and antifungal activity (Kulma et al. 2015).

Biosynthesis pathway of polyhydroxyalkanoates

The process of biosynthesis and PHA accumulation in microbial cells takes place in the cytoplasm. The type of polymer that is synthesized by the bacteria is closely related to the available food substrate. By performing various transformations, scientists try to get the accumulation of these polymers in different compartments of plant cells. The first characterized pathway of PHA biosynthesis was that of PHB biosynthesis. It consists of three stages catalyzed by three enzymes. These are: β-ketothiolase (denoted in literature as phaA or phbA), acetoacetyl-CoA reductase (phaB or phbB) and PHB synthase (phaC or phbC). The PHB biosynthesis pathway is schematically depicted in Fig. 2. The initial stage of biosynthesis is the condensation of two acetyl-CoA molecules catalyzed by phaA. The result of this reaction is the formation of acetoacetyl-CoA. Another intermediary in the PHB biosynthesis is 3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA, which is formed by the acetoacetyl-CoA reductions carried out by phaB. The process of polymerization is performed by the third enzyme called phaC (Kosseva and Rusbandi 2018).

Because of PHB’s physical properties, more commonly desired PHAs are PHBV or (P3HB4HB) copolymers. The PHBV biosynthesis pathway is a combination of two 3-hydroxybutyrate (HB) and 3-hydroxyvalerate (HV) pathways, which in the final stage are linked to each other by PHA synthase. The difference between the biosyntheses of HB and HV, which together take part in the PHBV biosynthesis pathway, is β-ketothiolase. The HV biosynthesis requires replacement of β-ketothiolase phaA with another β-ketothiolase called btkB. This replacement is necessary to realize the first stage of HV formation, in which the substrate for the reaction is propionic acid (Fig. 3). The enzyme btkB was found in R. eutropha and it catalyzes the condensation of acetyl-CoA and propionyl-CoA. It has greater specificity for propionyl-CoA than its counterpart in PHB biosynthesis (Poirier 2002).

The above-described PHAs belong to the group typically referred to as short-chain-length PHAs (scl-PHAs), which means that their monomers contain from 3 to 5 carbon atoms. In contrast, the monomers of long-chain length PHAs (lcl-PHAs) comprise more than 14 carbon atoms. The gap between (scl-PHAs) and (lcl-PHAs) is fulfilled by medium-chain-length PHAs (mcl-PHAs). The bacterial pathways of mcl-PHA biosynthesis are also known. Actually, there are two possible ways of PHA biosynthesis. The first one is based on intermediates of fatty acids β-oxidation and also on alkanoic acids. This is a complex process in which the levorotatory S-3-hydroxyacyl-CoA is transformed into the dextrorotatory enantiomer of this compound, i.e., R-3-hydroxyacyl-CoA by an enzyme called epimerase (Fig. 4). The second one uses products and intermediates of fatty acid biosynthesis. One of them is R-3-hydroxyacyl-ACP. The most important enzyme in this process is 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA-ACP transacylase (phaG). The purpose of this enzyme is to replace the Acyl Carrier Protein (ACP) by CoA. Both processes are completed by phaC (Kosseva and Rusbandi 2018) (Fig. 5).

(based on Kessel-Vigelius et al. 2013)

The mcl-PHA biosynthesis pathway occurring in peroxisomes of transgenic plants. This process uses the products and intermediates of β-oxidation of fatty acids (marked with bold arrows). Blue frames indicate the substrate, intermediate metabolites and product. Red frames indicate the enzymes catalyzing individual phases of mcl-PHA biosynthesis pathway. ACD Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, ECH enoyl-CoA hydratase, HCD L-3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase, KT β-ketothiolase

Pathways of PHA biosynthesis involving the fatty acid biosynthesis pathway (occurring in plastids) and the fatty acids β-oxidation (occurring in peroxisomes). Blue frames indicate the substrate, intermediate metabolites and product. Red frames indicate the following enzymes: PhaJ enoylo-CoA hydrate, FatB2 acyl-ACP thioesterase, KasA1 3-ketoacyl-ACP synthase

Localization of polyhydroxyalkanoates biosynthesis in transgenic plants

The biosynthesis of PHAs carried out by specific strains of bacteria in bioreactors is very expensive (Suriyamongkol et al. 2007). The high cost is determined by the amount and variety of food supply, sterility and optimization of growth conditions (Din et al. 2012). For comparison, the system for the biosynthesis of these compounds in plants is based on water, mineral salts, CO2 and light, which makes it cheap and environmentally friendly. In addition, plants are not capable of degrading PHAs as bacteria do. The biosynthesis of PHAs in transgenic plant cells is possible because of general availability of acetyl-CoA, the primary substrate in PHA biosynthesis. In plant cells, acetyl-CoA, is the major metabolite of catabolic and anabolic processes, including the cycle of tricarboxylic acids and the biosynthesis and degradation of fatty acids. Cellular compartments particularly rich in acetyl-CoA are cytoplasm, plastids, peroxisomes and mitochondria. All these cell compartments were taken under consideration in attempts to synthesize and accumulate various PHAs. It has been shown that the least effective structures for this purpose are mitochondria mainly due to the rapid use of acetyl-CoA in cellular respiration. PHAs have also been observed in vacuoles, probably as a result of pexophagy i.e., one of selective kinds of autophagy (Somleva et al. 2013).

Cytoplasm

The first experimental work described an attempt to synthesize PHB in cytoplasm of transgenic plants by engineering A. thaliana. The choice was made taking into account the presence of endogenous β-ketothiolase in the cytoplasm, which facilitated the design of genetic vectors that required only two out of three essential enzymes (Suriyamongkol et al. 2007; Kessel-Vigelius et al. 2013). The entire pathway of PHB biosynthesis in plants in the cytoplasm was based on the well-known bacterial process (Fig. 2). Nevertheless, no sufficiently high concentration of PHAs in the cytoplasm of plant cells that would allow a profitable extraction of these polymers has been achieved as yet. In addition, due to metabolic disorders in some species (e.g., A. thaliana), low growth and reduced seed production have been observed (Bohmert et al. 2000). Such undesirable effects of genetic transformation were due to acetyl-CoA and acetoacetyl-CoA deficiency because of its use in the pathways of plant hormone and sterols biosynthesis (Beilen and Poirier 2008).

Plastids

Plastids have two important advantages in terms of PHA biosynthesis. First of all, there is a high concentration of acetyl-CoA, which is mainly used for fatty acid biosynthesis. Second, these organelles work properly despite structural changes—they can naturally store relatively large starch granules without disturbance to their functioning. But plastids are not stocked with β-ketothiolase, which is located in the cytoplasm. This disadvantage, however, could be avoided by applying a suitable DNA encoding plastid targeting sequence. This specific sequence was located on the vectors encoding the enzymes needed for PHA biosynthesis. As shown by numerous studies, these organelles appear to be the best site for biosynthesis and accumulation of PHAs in transgenic plants because, except for leaf chlorosis, this process does not cause harmful side effects (Beilen and Poirier 2008). Apart from the biosynthesis of well-known PHB in plastids, attempts were also made with PHBV copolymer (Slater et al. 1999). This process is based on the bacterial PHBV biosynthesis pathway shown in Fig. 3.

Peroxisomes

Peroxisomes have a high potential for PHA biosynthesis in transgenic plants, primarily due to the high reductive strength of the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) forms involved in this process and their β-oxidation of fatty acids (Tilbrook et al. 2011). The process of β-oxidation of fatty acids is a series of fatty acid transformation reactions which eventually lead to acetyl-CoA. This process takes place throughout the life of the plant cell and is necessary for the rapid and effective growth of a young plant. Indeed, it allows depletion of stored lipids, but it is also essential for the recovery of carbon and other nutrients during aging (e.g., from degraded biological membranes) (Kessel-Vigelius et al. 2013). These organelles are of particular importance in the attempts at obtaining transgenic plants synthesizing mcl-PHAs as it has been proposed to use β-oxidation intermediates for their biosynthesis (Fig. 4). Such approaches are very important, although the introduction of all three necessary genes for the biosynthesis of even the simplest forms of PHAs directly into the peroxisome is very difficult (Tilbrook et al. 2011). Combined strategies to provide substrates in the form of exogenous fatty acids and to limit the biosynthesis of peroxisomal citrate are used to increase the productivity of mcl-PHAs in peroxisomes (Anderson et al. 2011).

Polyhydroxyalkanoates production in transgenic C3 plants

Arabidopsis thaliana

The first genetically modified plant producing PHAs was A. thaliana. The transformation was made in the beginning of 1990s and it has successfully brought about PHB accumulation in plant tissues. The PHB accumulation was at a level of 0.01% fresh mass and took place in cytoplasm, nucleus and vacuoles (Table 2). Although the yield was poor, the impact of the studies was enormous and the study has been a basis for further work on transgenic plants capable of biosynthesis of PHAs (Poirier et al. 1992). 2 years later a breakthrough studies brought transgenic A. thaliana plants capable of PHB accumulation at a level of 14% of dry mass (DW). This success was possible because of the localization of the enzymes catalyzing PHB biosynthesis in plastids. The transformation involved the use of three separate constructs comprising genes coding the enzymes needed for PHB biosynthesis. Each construct was a modified binary plasmid Ti originating from Agrobacterium tumefaciens, pBI 121. Each of the three vectors contained a sequence of chloroplast transit peptide from a Rubisco small subunit isolated from pea, a gene coding one of the PHAs enzymes and a synthetic linking sequence, under the control of cauliflower mosaic virus promoter. Three independent constructs were obtained: pBI-TP-Thio, pBI-TP-Red, pBI-TP-Syn, containing the genes of 3-ketothiolase, acetoacetyl-CoA reductase and PHB synthase. The most effective PHB biosynthesis was observed in the plants containing all three genes in their genome, which were obtained by cross-breeding. Unfortunately, the presence of chlorosis in the leaves of plants accumulating the highest amounts of the polymer could not be avoided (Nawrath et al. 1994).

Further studies on A. thaliana have been even more successful. In this plant, the highest documented level of PHA (to be exact PHB) production was achieved, which reached 4% of fresh mass so about 40% of DM. Biosynthesis and accumulation of PHB took place in plastids, but this time the construct applied contained all three genes needed for the PHB biosynthesis (Bohmert et al. 2000). The first phase of generation of multigene vector was similar to that described above, that is three independent constructs were made: pBI-TP-Thio, pBI-TP-Red and pBI-TP-Syn. The next step was the etching of pBI-TP-Red plasmid by the restriction enzymes HindIII and EcoRI. The fragment obtained was linked to the pBI-TP-Thio plasmid at the site HindIII, leading to a construct pBI AB. The etching of pBI-TP-Syn plasmid with HindIII and its partial etching with EcoRI, produced a molecule suitable for linking with the earlier linearized pBI AB leading to pBI ABC plasmid (Fig. 6a) (Bohmert et al. 2000). Further research conducted on A. thaliana led to PHB biosynthesis in plastids at 5.8–13.2% of DW (Bohmert et al. 2002), 6.4% of DW (Kourtz et al. 2005), and 14.0% (Kourtz et al. 2005). Arabidopsis thaliana was also used in comparative studies carried out on other transgenic plants synthetizing PHAs, which are described in further parts of the article.

Transforming part (T-DNA) of pBI ABC binary vector used for transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana (a) (Bohmert et al. 2000). T-DNA of PBH expression cassette used for transformation of poplar (b) (Dalton et al. 2012). T-DNA of pME22 plasmid used for transformation of the embryonic callus of oil palm (c) (Parveez et al. 2015). BAR The genes encoding phosphinothricin acetyltransferase (inactivating herbicide); EcoRI the restriction site recognized by EcoRI enzyme; greMP the minimal promoter with a glycocorticoid binding site; GRvH the gene encoding a glucocorticoid-responsive component; HINDIII the restriction site recognized by HINDIII enzyme; LB left T-DNA border; NPT II neomycin phosphotransferase gene; NT terminator of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens nopaline synthase gene; phbA, phbB, phbC the genes encoding the enzymes involved in the PHB biosynthesis pathway; Pnos promoter region of nopaline synthase gene of Agrobacterium tumefaciens; polyA polyadenyl fragment; UbiPro the maize ubiquitin promoter; RB right T-DNA border; 35S the Cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S promoter; TPSS gene encodes the transit peptide of the small subunit of Rubisco; TS gene encoding the plastidic directional sequence

Rapeseed (Brassica napus)

Seeds of oil plants seem to be suitable site for production of PHAs, first of all because they contain acetyl-CoA, needed for the biosynthesis of fatty acids. Rapeseed was the first genetically modified plant which accumulated PHAs in seeds. The transformations applied led to accumulation of PHB to 7.7% fresh mass and accumulation of PHBV copolymer to 2.3% DW. Both polymers were accumulated in leucoplasts because addition of special directional sequences to the gene constructs implemented. In both cases the seed-specific promotor to hydroxylase originating from Lesquerella fendleri was applied. This choice was made because its expression coincides in time with the process of fatty acids accumulation in seeds (Houmiel et al. 1999). The biosynthesis of PHBV copolymer is based on the earlier described process of PHB biosynthesis. However, this process needed some changes. The gene of PHA synthase (phbC) was isolated from Nocardia corallina, not as earlier from R. eutropha. The next step was a replacement of phbA gene with bktB one. Both genes code β-ketothiolase, however, the btkB enzyme from R. eutropha besides the biosynthesis of acetoacetyl-CoA is also able to synthesize 3-ketovaleryl-CoA and has higher specificity to propionyl-CoA. The earlier mentioned bktB and phbC genes were in the multigene construct together with the other two genes needed for the biosynthesis of PHBV genes, i.e., phbB and ilvA (gene coding threonine deaminase). The main problem was to obtain in the plant cell the fundamental substrate for PHBV biosynthesis, that is, propionyl-CoA. To solve this problem, the earlier mentioned ilvA gene, which transforms threonine into 2-ketobutyrate, was applied. Threonine deaminase is characterized with a greater resistance to inhibition by isoleucine than the endogenic enzyme, so it is more effective. In the next step, the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex localized in the plastid transforms 2-ketobutyrate in propionyl-CoA. Thus, produced substrates, by the action of the other enzymes (btkB, phbB and phbC), take part in the PHBV biosynthesis pathway (Fig. 3) (Slater et al. 1999).

In the same experiment also A. thaliana has been subjected to transformation with two vectors. The first comprised phbB and phbC genes, while the second included bktB and ilvA ones. All the genes were controlled by 35S promoter. These constructs contained also the sequence coding the subunit of the protein directing to chloroplasts. Unfortunately, the results were unsatisfactory as PHBV accumulation was at a level from 0.07 to 1.6% DW of the leaves (Slater et al. 1999).

Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum)

In attempts to obtain transgenic plants producing PHAs, much attention has been paid to N. tabacum. The first experiments were aimed at inducing the PHB production in cytoplasm, but similarly as for the experiments on the above-mentioned plant species, the results were unsatisfactory (Nakashita et al. 1999). On the basis of the experiments with A. thaliana, the genetic vector harboring three genes (phaA, phaB, and phaC) necessary for PHB biosynthesis was devised. The genes were controlled by the promoter of cauliflower mosaic virus 35S. The genes coding β-ketothiolase and acetoacetyl-CoA reductase were taken from R. eutropha, while the gene of PHA synthase was taken from Aeromonas caviae. The construct contained also the transit sequence of a tomato Rubisco small subunit. The transformation yielded PHB at a level of 0.16% of DW of aging leaves (Arai et al. 2001). In subsequent years, attempts were taken to improve this result. It was obtained by introducing bacteria operon coding all three enzymes necessary for PHB biosynthesis directly into the plastid DNA. This approach permitted avoiding a potential threat from spreading pollen of genetically modified plants containing the modified genome. Moreover, to enhance the level of expression of desired genes, the operon was equipped with the psbA gene, plastid-specific promoter, and the UTR flanking sequences. As a result of this experiment, the accumulation of PHB was 1.7% of DW obtained from young leaves (Lössl et al. 2003). A similar transformation based on directing the bacteria operon to chloroplast DNA was also performed. After some modifications, e.g., application of genes coding β-ketothiolase and PHA synthase from Acinetobacter sp. and acetoacetyl-CoA reductase from Bacillus megaterium, the accumulated PHB reached 18.8% of DM from certain leaves and 8.8% PHB in DW of the whole plant. The genes were used in the constructs because of the content of G/C pairs (guanine/cytosine) close to that in the DNA in N. tabacum chloroplasts (Bohmert-Tatarev et al. 2011).

Cotton (Gossypium sp.)

Successful expression of the genes of PHB biosynthesis was also performed in the cytoplasm of cotton cells. Cotton is known for producing fibers surrounding seeds, used in textile industry. Over 40% of the world’s demand for fiber is met by cotton. The genetic constructs used for the transformation of this plant included the genes coding phaB and phaC. They were controlled by E6 and FbL2A tissue-specific promoters engaged in particular stages of cotton fiber formation. As in the experiment with A. thaliana, the constructs did not have to contain the gene coding β-ketothiolase as it is a natural component of cotton cells cytoplasm. The PHB accumulation level varied from 0.003 to 0.34% in DW. It was not a satisfactory result, but such an accumulation resulted in formation of PHB inclusions in the fibers, which improved their properties (John 1997).

Flax (Linum usitatissimum)

Similarly as for cotton, the main aim of PHB biosynthesis in the flax cells was not the maximum PHB accumulation, but improvement of the mechanical properties of flax fibers as a result of the bioplastic inclusions. The first modifications of flax involved the transformation with one of the two vectors. The first contained all three genes of PHB biosynthesis (phaA, phaB, phaC), while the second contained only the first gene, coding β-ketothiolase. The plants transformed by the second vector were the control. In both constructs, phaA gene was controlled by the 14-3-3 stem-specific promoter. The expression of phaB and phaC genes was carried out by the promoter of cauliflower mosaic virus 35S. The modifications did not disturb the plant growth. An important effect was the increase in seed production and decrease in starch accumulation in chloroplasts. The PHB inclusions in fibers improved their elasticity and their resistance to tensile stress increased twice (Wróbel et al. 2004). In subsequent years, the studies were continued in the aspects of the content of phenolic compounds in the fibers of modified plants and the possibility of biomedical application of the fibers for wound dressing. It has been proved that this type of dressing made of flax fiber enhance the proliferation of human fibroblasts and showed antibacterial properties (Kulma et al. 2015).

Poplar tree (Populus sp.)

Poplar tree as a perennial plant of high mass increase rate seems to be a good object for investigation of modifications aimed at PHA accumulation. These polymers could be an addition to the fibers and biofuels obtained from poplar and—by enriching wood tissues—could be components of materials of new applications. So far the only PHA obtained in poplar wood tissue has been PHB. To avoid the adverse effects of PHB accumulation on the plant, the genetic constructs containing PHB biosynthesis genes were made to undergo expression only after activation by a chemical substance called methoxyfenozide. Besides the phaA, phaB and phaC genes under control of the ecdysone-based promoter, the construct included also NPT II, GRvH and TS genes. The NPT II gene codes the phosphotransferase of kanamycin, which by inactivation of kanamycin (antibiotic) permits a close selection of genetically modified plants. The GRvH gene codes the element responding to glucocorticoid, while the TS gene codes the plastid directional sequence (Fig. 6b). The ready construct was introduced into the plant via A. tumefaciens. The maximum PHB accumulation achieved was 2% PHB in DW, which was related to reduction in the growth rate (Dalton et al. 2012).

African oil palm (Elaeis guineensis)

African oil palm is an important source of edible oil used all over the world. The interest in African oil palm in the aspect of PHA biosynthesis comes from a high concentration of acetyl-CoA in plastids (Ismail et al. 2010). The transformation was achieved by the biolistic method in which metal dust particles of the size from about 0.5 µm to a few micrometers coated with DNA were introduced to the plant cells. The attempt, in which oil palm capable of PHB biosynthesis was obtained, involved embryogenic callus cells as a target of microinjection containing particles coated with pME22 plasmid. This plasmid comprised bktB, phaB, phaC genes, the bar gene coding phosphinothricin acetyltransferase responsible for resistance to herbicide Basta. The plasmid also contained the gene coding transit sequence of Rubisco small subunit, directing the PHB biosynthesis genes (bktB, phaB and phaC) to plastids. All genes were under control of maize ubiquitin promoter (UbiPro) and were ended with protecting polyadenylic fragment (polyA) (Fig. 6c). The final level of PHB accumulation in the tissues of transgenic oil palm varied from 0.033 to 0.058% of DW. Although these results seem rather poor, the outcome is considered pivotal as for the first time any PHB accumulation has been achieved in this plant species. The level of PHB accumulation can be changed with the plant aging, which is related to the fact that oil palm produces seeds rich in acetyl-CoA. The studies are underway (Parveez et al. 2015).

Camelina (Camelina sativa)

Transformation of this plant was performed with five binary vectors each of which containing three genes necessary for PHB biosynthesis (phaA, phaB, phaC), equipped with a plastid directional sequence and gene coding red fluorescence protein. Each vector contained a combination of seed-specific promoters. The constructs were introduced by the method based on A. tumefaciens. The most effective construct, leading to PHB accumulation at a level of 15% of DW, was the vector with phaB and phaC genes under control of oleosin promoter (oleosin—a protein, component of oleosome membrane), while the expression of phaA gene was controlled by glycinin-1 promoter (Malik et al. 2015). The highest PHB accumulation in seeds has been 19.9% of DW, however, the seedlings obtained from these seeds were weak and their growth was disrupted (Patterson et al. 2011).

Polyhydroxyalkanoates production in transgenic C4 plants

Successful experiments on PHA biosynthesis in plants carrying out C3 type photosynthesis prompted the studies on the possibility of PHA biosynthesis in highly energetically effective plants performing C4 type photosynthesis. These plant species are characterized by high mass increase rate, which is a consequence of high yield of nitrogen and water utility (Sage and Zhu 2011). The C4 photosynthesis species do not have high demands on soil, which makes them even more attractive for practical biotechnological applications (Somleva et al. 2013) and more resistant to dryness and cold (Sage and Zhu 2011).

Maize (Zea mays)

The first C4 photosynthesis plant genetically modified for the PHB biosynthesis was maize. All genes needed were located in a multigene vector. Their expression was controlled by a number of viral and plant promoters attached to the maize hsp70 intron. Thanks to the transit peptide of A. thaliana Rubisco small subunit, the entire construct was expressed in chloroplasts. The experiment brought the PHB accumulation at a level of 5.73% and 5.66% of DW. A high disproportion in PHB accumulation was noted between the chloroplasts of bundle sheath cells and mesophilic cells, the former ones were capable of storing greater amount of PHB granules. This observation led to a conclusion of inhomogeneous distribution of acetyl-CoA in the leaf tissues of C4 type biosynthesis plants (Somleva et al. 2013).

Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum)

Switchgrass is the first plant carrying out C4 photosynthesis with the use of malic enzyme dependent on the oxidized form of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD), to which PHA biosynthesis genes have been introduced. The construct used for the transformation contained phaA and phaB genes isolated from R. eutropha and phaC gene which was a hybrid of two synthases coming from Pseudomonas oleovorans and Zoogloea ramigera bacteria. The transforming part of the plasmid contained also a sequence of chloroplastic transit peptide of pea Rubisco small subunit and a marker gene coding phosphinothricin acetyltransferase. The two used promoters of rice ubiquitin II (rubi2) and chlorophyll (a and b) binding protein (cab-m5) permitted the biosynthesis of PHB accumulated to the amount of 0.01–1.82% of DW. The cam-m5 promoter permitted a higher level of expression than rubi2 in later stages of growth and development of transformed plants. Similarly, as in the other plants studied, the accumulation of PHB was higher in older leaf tissues and particularly low in the stem. Measurements were also made on the in vitro-cultivated plants. The PHB accumulation in these plants was greater than in the parental plants. Some of them were capable of PHB accumulation at the level of 6.09% of DW after transfer from in vitro conditions to soil.

Another method allowing increased level of PHB biosynthesis in switchgrass was the transformation via A. tumefaciens with an additional vector containing genes coding fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase and sedoheptulose-bisphosphatase. These enzymes have significantly improved the yield of photosynthesis and accelerated the plant growth. After 2 months of growing in the greenhouse, older leaf tissues accumulated PHB at levels up to 7.69% in DW (Somleva et al. 2013).

Sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum)

High mass increase rate is also a characteristic feature of sugarcane. The first attempts at PHB biosynthesis were based on the plant transformations through non-multigene constructs directed by special directional sequences to cytoplasm, mitochondria and plastids. The genes used were phaA, phaB and phaC from R. eutropha. To stimulate PHB biosynthesis in mitochondria, the genes were attached to the directing pre-sequence coding the β-subunit ATPase from Nicotiana plumbaginifolia. The above-mentioned genes were also directed to plastids through their attachment to the leader sequence of pea Rubisco small subunit. All constructs were under control of the constitutive promoter of maize ubiquitin (ubi1). Significant accumulation of PHB close to 1.88% of DW was observed only in leaf plastids (Petrasovits et al. 2007). Although the PHB accumulation in sugarcane was rather small, the studies were continued as long as no detectable side effects related to PHB, such as inhibited growth or leaf chlorosis, were noted. To increase the PHB accumulation in sugarcane leaves, both single-gene and multigene constructs were applied. The latter were in different sets under control of the promoter of maize ubiquitin (ubi1), rice ubiquitin II (rubi2), chlorophyll a and b binding protein promoter (cab-m5) and promoter from Cavendish banana streak badnavirus promoter. The most effective in PHB biosynthesis proved to be the promoter from Banana virus Cavendish. Unexpectedly, after 6 months of greenhouse cultivation, the level of accumulated PHB drastically decreased, which suggested silencing of the promoter with the plant aging. A probable reason could be the lack of intron below the Cv promoter in the genetic vector. No such phenomenon was observed when using cam-m5 whose control permitted the transgene expression despite leaf aging. With the use of this promoter, the PHB accumulation was close to 4.8% of DW. This promoter was for the first time used for sugarcane transformation, earlier it had been tested only with switchgrass, also a C4 photosynthesis plant. The highest PHB accumulation was achieved in chloroplasts of sugarcane bundle sheath cells, while the most important issue was the lack of considerable PHB accumulation in leaf mesophyll cells (Petrasovits et al. 2012). Two methods have been proposed to enhance the PHB accumulation in mesophyll cell plastids. The first involved inhibition of acetyl-CoA carboxylase which competes with β-ketothiolase for the substrate which is acetyl-CoA. The activity of acetyl-CoA carboxylase leads to malonyl-CoA which is a substrate for biosynthesis of fatty acids. The first plant in which the activity of acetyl-CoA carboxylase was successfully reduced was tobacco, later the success was repeated in sugarcane and switchgrass. The second method allowing increased accumulation of PHB in leaf mesophyll cells in the plants of C4 type photosynthesis is the introduction of plastid-directed NphT7 gene from Streptomyces sp. This gene codes the acetoacetyl-CoA synthase which carries out the condensation of acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA leading to formation of acetoacetyl-CoA. The acetoacetyl-CoA synthase uses twice less of acetyl-CoA than β-ketothiolase (phaA), which permits reduction of the loss of acetyl-CoA molecules which are substrates for important synthetic pathways of many plant compounds. Introduction of NphT7 gene to sugarcane has brought about the highest accumulation of PHB in leaf tissues of C4-type photosynthesis plants, which reached 11.8% of DW (McQualter et al. 2014).

Sugarcane and A. thaliana represent a group of plants in which attempts have been made to obtain PHA biosynthesis in peroxisomes. Arabidopsis thaliana was transformed with a plasmid containing all three genes needed for PHA biosynthesis (phaA, phaB, phaC), while the same genes were introduced to sugarcane in separate constructs. Both constructs contained a short, but effective sequence directing to peroxisomes (PTS1). The highest level of PHB accumulation in sugarcane, from 0.4 to 1.6% of DW, was observed in old plants, in particular in ends of the oldest leaves. Thanks to gas chromatography the presence of 3-hydroxybutyrate and 3-hydroxyvalerate monomers was detected in peroxisomes, and they finally made PHBV copolymer. The highest PHB accumulation of 1.8% of DW was obtained from the cells of A. thaliana seedlings after 4 days of growth in the dark. This result was in contrast to the results obtained for the seedlings growing under normal light condition in which the PHB accumulation was less than 0.1% of DW (Tilbrook et al. 2011).

Other polymers from a numerous PHA groups often chosen as subjects of studies are scl–mcl-PHAs copolymers. The interest in them stems from their complex structure and the possibility of modification of individual monomers, which opens the potential biosynthesis of target compounds. The transformation of sugarcane to induce biosynthesis of scl–mcl-PHAs copolymers in peroxisomes was performed with a multigene construct containing the genes needed for PHB biosynthesis: phbA, phbB and phaC2 from Pseudomonas fluorescens. The latter gene codes the enzyme that has a stronger affinity to the substrates than the catalytic proteins coded by other phaC. This construct contained also PhaJ gene that codes enoyl-CoA hydratase, FatB2 gene coding acyl-ACP thioesterase and KasA1 gene coding 3-ketoacyl-ACP whose responsibility was to increase the amount of fatty acids synthesized in plastids (Fig. 5). The obtained fatty acids were next the substrates for β-oxidation reaction which contributed to increased biosynthesis of scl–mcl-PHAs copolymer in peroxisomes. The genes needed for the biosynthesis of the scl and mcl semi-products were equipped with a sequence directing to peroxisomes called RAVARL. The other two genes had the native plastid sequence. All the genes were in six separate vectors. The transformation of embryonic callus was carried out by the biolistic methods. The final PHA accumulation in sugarcane was 0.015% of leaf DW (Anderson et al. 2011).

Conclusions and perspectives

The wide range of applications and the biodegradability of PHAs are the main attractive features stimulating the over 20 years efforts for the biosynthesis of these polymers by plants through complex genetic modifications. Undoubtedly, one of the most important studies was conducted on a well-known model plant, A. thaliana. So far, the highest level of biopolymer accumulation in the PHB form has been achieved in this very plant. However, A. thaliana is not a crop that could be used as a specific bioreactor for PHAs production on a wide scale. Recently, the attention has been directed to oil, fibrous and other plants that have increased metabolism of acetyl CoA. The challenge still remains to increase the efficiency of PHAs accumulation and improve the condition of tissues in which polymers accumulate. Energy-efficient bio-energy plants that perform C4 photosynthesis are also much interesting. Thanks to a more efficient CO2 binding process, these plants offer potentially better site for PHA biosynthesis than C3 plants (Table 2).

There are many issues related to PHAs production in genetically modified plants such as the process of the plant’s transformation, the expression of the transformed genes in the future generations or the complicated and expensive way of extraction from intracellular compartments. It seems that the most likely scenario is that in the future the mass scale generation of PHAs will be performed with the use of various modified strains of bacteria (Constantina et al. 2017), in vitro enzymatic biosynthesis of PHAs or chemo-biosynthesis (Gumel et al. 2013). However, transgenic plants are very promising because they can accumulate PHAs at a high level. For instance, accumulation of PHB at the level of 15% in C. sativa seeds was obtained without negative side effects (Malik et al. 2015). The level about 20% in Camelina seeds was also achieved, but the seed germination and seedling growth was significantly impaired (Patterson et al. 2011). Nonetheless, it does not end the potential use of genetically transformed plants in this field as illustrated by the results achieved for gossypium (John 1997) and flax (Wróbel et al. 2004; Kulma et al. 2015) in which the level of PHAs is not as high as in Camelina, but in the case of these plants PHAs do not require the extraction from intracellular compartments. The strategies of PHAs production are still limited because of high costs, but due to increasing demand on biodegradable resources in the near future, they should be further developed to obtain highly efficient bioprocesses, and transgenic plants have huge potential in this field.

Author contribution statement

JD wrote the draft of the manuscript, prepared all tables and figures, and was involved in writing of the final version of the manuscript, MS and RL were involved in writing of the manuscript and literature screening, SB formulated conception of the manuscript and supervised all stages of writing of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- 3HB:

-

(R)-3-hydroxybutyrate

- ACD:

-

Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase

- ACP:

-

Acyl carrier protein

- btkB:

-

β-Ketothiolase which has a higher specificity for propionyl-CoA

- ECH:

-

Enoyl-CoA hydratase I

- FatB2:

-

Thioesterase acyl-ACP

- HCD:

-

S-3 hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase

- HV:

-

3-Hydroxyvalerate

- KasA1:

-

3-Ketoacyl-ACP synthase

- P3HB4HB:

-

Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-4-hydroxybutyrate)

- P4HB:

-

Poly-4-hydroxybutyrate

- PHAs:

-

Polyhydroxyalkanoates

- phaA (or phbA):

-

β-Ketothiolase

- phaB (or phbB):

-

Acetoacetyl-CoA reductase

- phaC (or phbC):

-

PHA synthase

- PhaJ:

-

Enoyl-CoA hydratase

- PHB:

-

Polyhydroxybutyrate

- PHBHHx:

-

Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3- hydroxyhexanoate)

- PHBV:

-

Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate)

- PHBVHHx:

-

Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate)

- PHV:

-

Polyhydroxyvalerate

References

Anderson DJ, Gnanasambandam A, Mills E, O Shea MG, Nielsen LK, Brumbley DW (2011) Synthesis of short-chain-length/medium-chain length polyhydroxy-alkanoate (PHA) copolymers in peroxisomes of transgenic sugarcane. Trop Plant Biol 4:170–184

Anjum A, Zuber M, Zia KM, Noreen A, Anjum MN, Tabasum S (2016) Microbial production of polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) and its copolymers: a review of recent advancements. Int J Biol Macromol 89:161–174

Arai Y, Nakashita H, Doi Y, Yamaguchi I (2001) Plastid targeting of polyhydroxybutyrate biosynthetic pathway in tobacco. Plant Biotechnol 18:289–293

Arai Y, Nakashita H, Suzuki Y, Kobayashi Y, Shimizu T. Yasuda M, Doi Y, Yamaguchi I (2002) Synthesis of a novel class of polyhydroxyalkanoates in Arabidopsis peroxisomes, and their use in monitoring short-chain-length intermediates of β-oxidation. Plant Cell Physiol 43:555–562

Arai Y, Shikanai T, Doi Y, Yoshida S, Yamaguchi I, Nakashita H (2004) Production of polyhydroxybutyrate by polycistronic expression of bacterial genes in tobacco plastid. Plant Cell Physiol 45:1176–1184

Baikar V, Rane A, Deopurkar R (2017) Characterization of polyhydroxyalkanoate produced by Bacillus megaterium VB89 isolated from nisargruna biogas plant. App Biochem Biotech 183:241–253

Beilen JBV, Poirier Y (2008) Production of renewable polymers from crop plants. Plant J 54:684–701

Bohmert K, Balbo I, Kopka J, Mittendorf V, Nawrath C, Poirier Y, Tischendorf G, Trethewey RN, Willmitzer L (2000) Transgenic Arabidopsis plants can accumulate polyhydroxybutyrate to up to 4% of their fresh weight. Planta 211:841–845

Bohmert K, Balbo I, Steinbuchel A, Tischendorf G, Willmitzer L (2002) Constitutive expression of the β-ketothiolase gene in transgenic plants. A major obstacle for obtaining polyhydroxybutyrate-producing plants. Plant Physiol 128:1282–1290

Bohmert-Tatarev K, McAvoy S, Daughtry S, Peoples OP, Snell KD (2011) High levels of bioplastic are produced in fertile transplastomic tobacco plants engineered with a synthetic operon for the production of polyhydroxybutyrate. Plant Physiol 155:1690–1708

Chanprateep S (2010) Current trends in biodegradable polyhydroxyalkanoates. J Biosci Bioeng 110:621–632

Chen GQ (2009) A microbial polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) based bio- and materials industry. Chem Soc Rev 38:2434–2446

Constantina K, Plácido J, Venetsaneas N, Burniol-Figols A, Varrone C, Gavala HN, Reis MAM (2017) Recent advances and challenges towards sustainable polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) production. Bioengineering 4:55

Dalton DA, Ma C, Murthy GS, Strauss SH (2012) Bioplastic production by transgenic poplar. ISB News Rep January: 7–10

Din MF, Mohanadoss P, Ujang Z, van Loosdrecht M, Yunus SM, Chelliapan S, Zambare V, Olsson G (2012) Development of Bio-PORec® system for polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) production and its storage in mixed cultures of palm oil mill effluent (POME). Bioresour Technol 124:208–216

Endo N, Yoshida K, Akiyoshi M, Manji S (2006) Hybrid fiber production: a wood and plastic combination in transgenic rice and Tamarix made by accumulating poly-3-hydroxybutyrate. Plant Biotechnol 23:99–109

Gumel AM, Annuar MSM, Chisti Y (2013) Recent advances in the production, recovery and applications of polyhydroxyalkanoates. J Polym Environ 21:580–605

Hahn JJ, Eschenlauer AC, Sleytr UB, Somers DA, Srienc F (1999) Peroxisomes as sites for synthesis of polyhydroxyalkanoates in transgenic plants. Biotechnol Prog 15:1053–1057

Houmiel KL, Slater S, Broyles D, Casagrande L, Colburn S, Gonzalez K, Mitsky TA, Reiser SE, Shah D, Taylor NB, Tran M, Valentin HE, Gruys KJ (1999) Poly(beta-hydroxybutyrate) production in oilseed leukoplasts of Brassica napus. Planta 209:547–550

Ismail I, Iskandar NF, Chee GM, Abdullah R (2010) Genetic transformation and molecular analysis of polyhydroxybutyrate biosynthetic gene expression in oil palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq. var Tenera) tissues. Plant Omics J 1:18–27

John ME (1997) Cotton crop improvement through genetic engineering. Crit Rev Biotechnol 17:185–208

Kessel-Vigelius SK, Wiese J, Schroers MG, Wrobel TJ, Hahn F, Linka N (2013) An engineered plant peroxisome and its application in biotechnology. Plant Sci 210:232–240

Koller M (2018) Biodegradable and biocompatible polyhydroxy-alkanoates (PHA): auspicious microbial macromolecules for pharmaceutical and therapeutic applications. Molecules 23(2):362

Kosseva MR, Rusbandi R (2018) Trends in the biomanufacture of polyhydroxyalkanoates with focus on downstream processing. Int J Biol Macromol 107:762–778

Kourtz L, Dillon K, Daughtry S, Madison LL, Peoples O, Snell KD (2005) A novel thiolase-reductase gene fusion promotes the production of polyhydroxybutyrate in Arabidopsis. Plant Biotechnol J 3:435–447

Kourtz L, Dillon K, Daughtry S, Peoples OP, Snell KD (2007) Chemically inducible expression of the PHB biosynthetic pathway in Arabidopsis. Transgenic Res 16:759–769

Kulma A, Skórkowska-Telichowska K, Kostyn K, Szatkowski M, Skała J, Drulis-Kawa Z, Preisner M, Żuk M, Szperlik J, Wang YF, Szopa J (2015) New flax producing bioplastic fibers for medical purposes. Ind Crops Prod 68:80–89

Lössl A, Eibl C, Harloff H-J, Jung C, Koop H-U (2003) Polyester synthesis in transplastomic tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.): significant contents of polyhydroxybutyrate are associated with growth reduction. Plant Cell Rep 21:891–899

Lössl A, Bohmert K, Harloff H, Eibl C, Muhlbauer S, Koop HU (2005) Inducible trans-activation of plastid transgenes: expression of the R. eutropha phb operon in transplastomic tobacco. Plant Cell Physiol 46:1462–1471

Malik MR, Yang W, Patterson N, Tang J, Wellinghoff RL, Preuss ML, Burkitt C, Sharma N, Ji Y, Jez JM, Peoples OP, Jaworski JG, Cahoon EG, Snell KD (2015) Production of high levels of poly-3-hydroxybutyrate in plastids of Camelina sativa seeds. Plant Biotechnol J 13:675–688

Masood F, Yasin T, Hameed A (2014) Polyhydroxyalkanoates—what are the uses? Current challenges and perspectives. Crit Rev Biotechnol 35:514–521

Matsumoto K, Nagao R, Murata T, Arai Y, Kichise T, Nakashita H, Taguchi S, Shimada H, Doi Y (2005) Enhancement of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) production in the transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana by the in vitro evolved highly active mutants of polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) synthase from Aeromonas caviae. Biomacromol 6:2126–2130

Matsumoto K, Arai Y, Nagao R, Murata T, Takase K, Nakashita H, Taguchi S, Shimada H, Doi Y (2006) Synthesis of short-chain-length/medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) copolymers in peroxisome of the transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana harboring the PHA synthase gene from Pseudomonas. J Polym Environ 14:369–374

Matsumoto K, Murata T, Nagao R, Nomura CT, Arai S, Arai Y, Takase K, Nakashita H, Taguchi S, Shimada H (2009) Production of short-chain-length/medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) copolymer in the plastid of Arabidopsis thaliana using an engineered 3-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase III. Biomacromol 10:686–690

Matsumoto K, Morimoto K, Gohda A, Shimada H, Taguchi S (2011) Improved polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) production in transgenic tobacco by enhancing translation efficiency of bacterial PHB biosynthetic genes. J Biosci Bioeng 111:485–488

McQualter RB, Petrasovits LA, Gebbie LK, Schweitzer D, Blackman D, Plan M, Hodson M, Riches J, Snell KD, Brumbley DW, Nielsen L (2014) The use of an acetoacetyl-CoA synthase in place of a β-ketothiolase enhances poly-3-hydroxybutyrate production in sugarcane mesophyll cells. Plant Biotechnol J 10:569–578

Menzel G, Harloff H-J, Jung C (2003) Expression of bacterial poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) synthesis genes in hairy roots of sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L.). Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 60:571–576

Mitsky TA, Slater S, Reiser SE, Hao M, Houmiel KL (2003) Multigene expression vectors for the biosynthesis of products via multienzyme biological pathways. US Patent Application 2003/0182678

Mittendorf V, Robertson EJ, Leech RM, Kruger N, Steinbuchel A, Poirier Y (1998) Synthesis of medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoates in Arabidopsis thaliana using intermediates of peroxisomal fatty acid β-oxidation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:13397–13402

Nakashita H, Arai Y, Yoshioka K, Fukui T, Doi Y, Usami R, Horikoshi K, Yamaguchi I (1999) Production of biodegradable polyester by a transgenic tobacco. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 63:870–874

Nakashita H, Arai Y, Shikanai T, Doi Y, Yamaguchi I (2001a) Introduction of bacterial metabolism into higher plants by polycistronic transgene expression. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 65:1688–1691

Nakashita H, Arai Y, Suzuki Y, Yamaguchi I (2001b) Molecular breeding of transgenic tobacco plants which accumulate polyhydroxyalkanoates. RIKEN Rev 42:67–70

Nawrath C, Poirier Y, Somerville C (1994) Targeting of the polyhydroxybutyrate biosynthetic pathway to the plastids of Arabidopsis thaliana results in high levels of polymer accumulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91:12760–12764

Parveez GKA, Bahariah B, Ayub NH, Masani MAM, Rasid OA, Tarmizi AH, Ishak Z (2015) Production of polyhydroxybutyrate in oil palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) mediated by microprojectile bombardment of PHB biosynthesis genes into embryogenic calli. Front Plant Sci 6:1–12

Patterson N, Tang J, Cahoon EB, Jaworski JG, Wang W, Peoples OP, Snell KD (2011) Generation of high polyhydroxybutryate producing oilseeds. International Patent Application WO/2011/034945

Petrasovits LA, Purnell MP, Nielsen LK, Brumbley DW (2007) Production of polyhydroxybutyrate in sugarcane. Plant Biotechnol J l 5:162–172

Petrasovits LA, Zhao L, McQualter RB, Snell KD, Somleva MN, Patterson NA, Nielsen LK, Brumbley DW (2012) Enhanced polyhydroxybutyrate production in transgenic sugarcane. Plant Biotechnol 10:569–578

Poirier Y (2002) Polyhydroxyalkanoate synthesis in plants as a tool for biotechnology and basic studies of lipid metabolism. Prog Lipid Res 41:131–155

Poirier Y, Dennis DE, Klomparens K, Somerville C (1992) Polyhydroxybutyrate, a biodegradable thermoplastic, produced in transgenic plants. Science 256:520–523

Poirier Y, Somerville C, Schechtman LA, Satkowski MM, Noda I (1995) Synthesis of high-molecular-weight poly([R]-(-)-3-hydroxybutyrate) in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana plant cells. Int J Biol Macromol 17:7–12

Poirier Y, Ventre G, Caldelari D (1999) Increased flow of fatty acids toward β-oxidation in developing seeds of Arabidopsis deficient in diacylglycerol acyltransferase activity or synthesizing medium-chain-length fatty acids. Plant Physiol 121:1359–1366

Purnell MP, Petrasovits LA, Nielsen LK, Brumbley DW (2007) Spatio-temporal characterisation of polyhydroxybutyrate accumulation in sugarcane. Plant Biotechnol J 5:173–184

Romano A, van der Plas LHW, Witholt B, Eggink G, Mooibroek H (2005) Expression of poly-3®hydroxyalkanoate (PHA) polymerase and acyl-CoA-transacylase in plastids of transgenic potato leads to the synthesis of a hydrophobic polymer, presumably medium-chain-length PHAs. Planta 220:455–464

Sabbagh F, Muhamad II (2017) Production of poly-hydroxyalkanoate as secondary metabolite with main focus on sustainable energy. Renew Sust Energy Rev 72:95–104

Sage RF, Zhu XG (2011) Exploiting the engine of C4 photosynthesis. J Exp Bot 62:2989–3000

Saruul P, Srienc F, Somers DA, Samac DA (2002) Production of a biodegradable plastic polymer, poly-β-hydroxybutyrate, in transgenic alfalfa. Crop Sci 42:919–927

Schnell J, Treyvaud-Amiguet V, Arnason J, Johnson D (2012) Expression of polyhydroxybutyric acid as a model for metabolic engineering of soybean seed coats. Transgenic Res 21:895–899

Sharma L, Srivastava JK, Singh AK (2016) Biodegradable polyhydroxyalkanoate thermoplastics substituting xenobiotic plastics: a way forward for sustainable environment. In: Singh A, Prasad S, Singh R (eds) Plant responses to xenobiotics. Springer, Singapore, pp 317–346

Singh M, Kumar P, Ray S, Kalia VC (2015) Challenges and opportunities for customizing polyhydroxyalkanoates. Ind J Microbiol 55:235–249

Slater S, Mitsky TA, Houmiel KL, Hao M, Reiser SE, Taylor NB, Tran M, Valentin HE, Rodriguez DJ, Stone DA, Padgette SR, Kishore G, Gruys KJ (1999) Metabolic engineering of Arabidopsis and Brassica for poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) copolymer production. Nat Biotechnol 17:1011–1016

Snell KD, Singh V, Brumble DW (2015) Production of novel biopolymers in plants: recent technological advances and future prospects. Curr Opin Biotechnol 32:68–75

Somleva M, Ali A (2010) Propagation of transgenic plants. International Patent Application WO/2010/102220

Somleva MN, Snell KD, Beaulieu JJ, Peoples OP, Garrison BR, Patterson NA (2008) Production of polyhydroxybutyrate in switchgrass, a value-added co-product in an important lignocellulosic biomass crop. Plant Biotechnol J 6:663–678

Somleva M, Chinnapen H, Ali A, Snell KD, Peoples OP, Patterson N, Tang J, Bohmert-Tatarev K (2012) Increasing carbon flow for polyhydroxybutyrate production in biomass crops. US Patent Application 2012/0060413

Somleva MN, Peoples OP, Snell KD (2013) PHA bioplastics, biochemicals, and energy from crops. Plant Biotechnol J 11:233–252

Suriyamongkol P, Weselake R, Narine S, Moloney M, Shah S (2007) Biotechnological approaches for the production of polyhydroxyalkanoates in microorganisms and plants—a review. Biotechnol Adv 25:148–175

Suzuki Y, Kurano M, Arai Y, Nakashita H, Doi Y, Usami R, Horikoshi K, Yamaguchi I (2002) Enzyme inhibitors to increase poly-3-hydroxybutyrate production by transgenic tobacco. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 66:2537–2542

Tan GYA, Chen CL, Li L, Ge L, Wang L, Razaad IMN, Li Y, Zhao L, Mo Y, Wang JY (2014) Start a research on biopolymer polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA): a review. Polymers 6:706–754

Tilbrook K, Gebbie L, Schenk PM, Poirier Y, Brumbley DW (2011) Peroxisomal polyhydroxyalkanoate biosynthesis is a promising strategy for bioplastic production in high biomass crops. Plant Biotechnol J 9:958–969

Valentin HE, Broyles DL, Casagrande LA, Colburn DW, Creely WL, DeLaquil PA, Felton HM, Gonzalez KA, Houmiel KL, Lutke K, Mahadeo DA, Mitsky TA, Padgette SR, Reiser SE, Slater S, Stark DM, Stock RT, Stone DA, Taylor NB, Thorne GM, Tran M, Gruys K (1999) PHA production, from bacteria to plants. Int J Biol Macromol 25:303–306

Volova TG, Vinogradova ON, Zhila NO, Kiselev EG, Sukovatiy AG, Shishatskaya EI (2016) Properties of a novel quaterpolymer P(3HB/4HB/3HV/3HHx). Polymer 101:67–74

Wang Y, Wu Z, Zhang X, Chen G, Wu Q, Huang C, Yang Q (2005) Synthesis of medium-chain-length-polyhydroxyalkanoates in tobacco via chloroplast genetic engineering. Chin Sci Bull 50:1113–1120

Wang L, Wang ZH, Shen CY, You ML, Xiao JF, Chen GQ (2010) Differentiation of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells grown in terpolyesters of 3-hydroxyalkanoates scaffolds into nerve cells. Biomaterials 31:1691–1698

Wróbel M, Zebrowski J, Szopa J (2004) Polyhydroxybutyrate synthesis in transgenic flax. J Biotechnol 107:41–54

Wróbel-Kwiatkowska M, Zebrowski J, Starzycki M, Oszmianski J, Szopa J (2007) Engineering of PHB synthesis causes improved elastic properties of flax fibers. Biotechnol Prog 23:269–277

Wróbel-Kwiatkowska M, Skórkowska-Telichowska K, Dymińska L, Mączka M, Hanuza J, Szopa J (2009) Biochemical, mechanical, and spectroscopic analyses of genetically engineered flax fibers producing bioplastic (poly-β-hydroxybutyrate). Biotechnol Prog 25:1489–1498

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by M. H. Walter.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Dobrogojski, J., Spychalski, M., Luciński, R. et al. Transgenic plants as a source of polyhydroxyalkanoates. Acta Physiol Plant 40, 162 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11738-018-2742-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11738-018-2742-4