Abstract

Two developments have marked EU democracies, with different levels of incidence and intensity, during the past two decades: the decline in support for democracy and the spread of corruption. Most individual-level analyses have identified the incumbent’s economic performance or government effectiveness as sufficient explanations of citizens’ growing dissatisfaction with democracy; whilst corruption has been downplayed as an explanatory variable by these multifactor analyses. We contend that this has partly to do with conceptual and methodological failings in the way perceptions about the phenomenon are measured. Defining corruption as abuse of office is insufficient to understand how perceptions about the decline of ethical standards in public life can be relevant to shape specific support for democracy. In this article, we propose an alternative conceptualization that goes beyond what is proscribed in the penal codes and special criminal laws, which the literature has recently defined as legal/institutional corruption, and demonstrate how it can offer an interesting explanation of citizens’ perceptions of the way democracy works in a European context (EU-27 member states).

Source: European Commission (2013, p. 72)

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

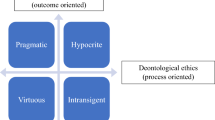

Mainstream conceptualisations of corruption tend to focus on bribery and relate to what is known as pocketbook evaluations, i.e. judgements driven by personal experience (see Klašnja et al. 2014, p. 70; Klašnja and Tucker 2013, p. 537), in contrast to a conceptualization of corruption linked to a broader moral (and also political) decay of the quality of government performance, the so-called sociotropic evaluations, i.e. judgements which take into account the notion of collective interest (Meehl 1977, p. 14).

27 member states of the EU were evaluated here: Austria (AT), Belgium (BE), Bulgaria (BG), Cyprus (CY), Czech Republic (CZ), Denmark (DE), Estonia (EE), Finland (FI), France (FR), Germany (DE), Greece (EL), Hungary (HU), Ireland (IE), Italy (IT), Latvia (LV), Lithuania (LT), Luxembourg (LU), Malta (MT), Netherlands (NL), Poland (PL), Portugal (PT), Romania (RO), Slovakia (SK), Slovenia (SI), Spain (ES), Sweden (SE), and United Kingdom (UK). Croatia was not considered in the research due to the high number of invalid entries present in the database provided by the European Commission (see 2017a).

Satisfaction with democracy used the micro-data provided by European Commission (2017a) in its standard Eurobarometer no. 79.3. Macro-level results related to satisfaction with democracy considered information of the report Public Opinion in the European Union—Standard Eurobarometer no. 79 (European Commission 2013, p. 72). Eurobarometer 79 consulted 27,105 people aged 15 years and over from 27 EU member states between the 10th and 26th of May 2013.

Such index is based on the aggregate-level results of the special issue no. 397 of the Eurobarometer series (European Commission 2014, p. 13, 46, and 56). This survey interviewed 26,786 people aged 15 years and over from 27 member states of the European Union (EU) between the 23rd February and the 10th March 2013.

Political attitudes (such as political participation, representation, quality of government, and corruption) sometimes appear as explanatory variables of DwD, influenced by macroeconomic determinants or micro-level sociographics (see for e.g. Dahlberg et al. 2015; Quaranta and Martini 2017; Stockemer and Sundström 2013). Foster and Frieden (2017, p. 21), for example, show that political institutions are secondary to economic factors in explaining trust in the democratic functioning of European countries. However, they only focus on the short-term change in levels of trust. Political factors (including ‘beyond the law’ aspects of corruption) matter to explain long-term rather than short-term regime performance. The widespread dissatisfaction with democracy is the result of a lengthy and corrosive process, in which current economic results usually blur the boundaries between what constitutes amoral and corrupt behaviour. Poor macroeconomic records may exert a short-term influence on the perceived dissatisfaction with the way democratic works, but only a sociotropic-oriented political corruption makes such dissatisfaction endemic, resilient and increasingly pronounced.

A principal component analysis was used to merge all legal corruption dimensions into one. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure confirmed sample adequacy (KMO = 0.645) for the proposed one-scale reduction, Bartlett's test of sphericity was significant at a 1% level, and Kaiser eigenvalue criterion was obeyed (explaining 68.16% of the variance in a single factor).

Sociographic individual-level variables and political determinants (at micro and macro levels) are usually used in studies about DwD and corruption as controls (Dahlberg et al. 2015; Pellegata and Memoli 2016; Quaranta and Martini 2017; Stockemer and Sundström 2013; Wagner et al. 2009). Macroeconomic factors, albeit typically used in DwD studies, serve to determine in which circumstances economic outcomes exert influence on political support at the aggregate level. Recent literature suggests that citizens tend to become particularly sensitive to occurrences of corruption affecting political actors, institutions, and processes in contexts of economic crisis (Choi and Woo 2010; Zechmeister and Zizumbo-Colunga 2013).

Table 3 in the Appendix details the full operationalization of all control variables used.

Random-effects logit models were built using the Stata command ‘xtlogit’ and were grouped by countries.

All these studies were based on common sense concepts of corruption that describe it, with minor differences, as “the abuse of public office for private gain” (World Bank 1997, p. 8) or as “the abuse of entrusted power for private gain” (Transparency International 2016). In essence, they considered only illegal aspects of corruption (Anderson and Tverdova 2003, p. 92; Dahlberg et al. 2015, p. 32; Memoli and Pellegata 2013, p. 14; Mishler and Rose 2001, p. 317; Pellegata and Memoli 2016, p. 395; Stockemer and Sundström 2013, pp. 144–146; Wagner et al. 2009, p. 40) and neglected what matters the most: its capacity to create manipulation of public policies and market regulations.

In multilevel models, when ρ (rho)—i.e. the proportion of total variance contributed by the panel-level variance—is 0, the panel-level variance component is unimportant and there is no need to run multilevel models. In this research, rho differs from 0 in all models, what constitutes an evidence for considering differences among countries. However, the values also indicate that the observations (albeit geographically dispersed) are homogenous throughout the entire set of European countries.

‘International experience’ presents promising results. It indicates that the more citizens visit other EU countries, the less they discredit their own national democracies. Future research is needed to disentangle such relation.

‘Urbanization’ (area of residence rural/urban) and ‘age’ present certain level of statistical significance (1 and 10%, respectively) and display coefficients near 0 (− 0.038 and − 0.006, respectively), what makes their contribution to the model extremely limited. Moreover, it is possible to argue that the relation rural-dissatisfaction raises a distributive problem because large cities concentrate public services and are central to the design of contemporary public policies. ‘Age’ could be seen as a complementary variable that describes intergenerational differences about DwD, young people have been facing difficulties in finding formal jobs, thus making them more susceptible of criticizing democratic performance and connect their evaluations with the 2008/2010 economic crises discourse.

The quality of national institutions was measured considering five dimensions of the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI): voice and accountability, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, the rule of law, and the control of corruption (see Kaufmann et al. 2009). In this case, corruption was indirectly used to perform the econometric exercises.

Institutional quality here refers to “an index developed by the International Country Risk Guide that provides a monthly rating of a country’s bureaucratic quality, level of corruption, and, government responsiveness” (for more information, see Foster and Frieden 2017, p. 8 and note 6). Albeit indirectly, corruption was used to evaluate levels of trust in governments.

See also Lange and Onken (2013).

References

Aarts, K., & Thomassen, J. (2008). Satisfaction with democracy: Do institutions matter? Electoral Studies, 27(1), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2007.11.005.

Anderson, C. J., & Tverdova, Y. V. (2003). Corruption, political allegiances, and attitudes toward government in contemporary democracies. American Journal of Political Science, 47(1), 91–109. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-5907.00007.

Armingeon, K., & Guthmann, K. (2014). Democracy in crisis? The declining support for national democracy in European countries, 2007–2011. European Journal of Political Research, 53(3), 423–442. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12046.

Bagashka, T. (2013). Unpacking corruption: The effect of veto players on state capture and bureaucratic corruption. Political Research Quarterly, 67(1), 165–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912913492584.

Bailey, J., & Paras, P. (2006). Perceptions and attitudes about corruption and democracy in Mexico. Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos, 22(1), 57–82.

Bauhr, M., Nasiritousi, N., Oscarsson, H., & Persson, A. (2010). Perceptions of corruption in Sweden. QoG working paper series (Vol. 8), Gothenburg, Sweden.

Becquart-Leclercq, J. (1984). Paradoxes de la corruption politique. Pouvoirs, revue française d’études constitutionnelles et politiques, 31, 19–36.

Brathwaite, R. T. (2015). Social distortion: Democracy and social aspects of religion—State separation. Journal of Church and State, 57(2), 310–332. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcs/cst095.

Canache, D., & Allison, M. E. (2005). Perceptions of political corruption in Latin American democracies. Latin American Politics and Society, 47(3), 91–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-2456.2005.tb00320.x.

Castro, C. (2008). Determinantes económicos da corrupção na União Europeia dos 15. Economia Global e Gestão, 13(3), 71–98.

Choi, E., & Woo, J. (2010). Political corruption, economic performance, and electoral outcomes: A cross-national analysis. Contemporary Politics, 16(3), 249–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2010.501636.

Clarke, H. D., Dutt, N., & Kornberg, A. (1993). The political economy of attitudes toward polity and society in Western European. The Journal of Politics, 55(4), 998–1021. https://doi.org/10.2307/2131945.

Criado, H., & Herreros, F. (2007). Political support. Comparative Political Studies, 40(12), 1511–1532. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414006292117.

Curini, L., Jou, W., & Memoli, V. (2012). Satisfaction with democracy and the winner/loser debate: The role of policy preferences and past experience. British Journal of Political Science, 42(2), 241–261. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123411000275.

Dahlberg, S., Linde, J., & Holmberg, S. (2015). Democratic discontent in old and new democracies: Assessing the importance of democratic input and governmental output. Political Studies, 63(1_suppl), 18–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.12170.

Dalton, R. J. (1999). Political support in advanced industrial democracies. In P. Norris (Ed.), Critical citizens: Global support for democratic government (pp. 57–77). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

De Sousa, L. (2002). Corruption: Assessing ethical standards in political life through control policies. Doctoral thesis. Florence: European University Institute.

De Sousa, L. (2005). Reacções da opinião pública à corrupção e descontentamento com a democracia. In J. M. L. Viegas, A. C. Pinto, & S. Faria (Eds.), Democracia: novos desafios e novos horizontes (pp. 277–302). Oeiras: Celta.

De Sousa, L. (2008). ‘I Don’t Bribe, I Just Pull Strings’: Assessing the fluidity of social representations of corruption in Portuguese society. Perspectives on European Politics and Society, 9(1), 8–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/15705850701825402.

De Sousa, L., Magalhães, P. C., & Amaral, L. (2014). Sovereign debt and governance failures: Portuguese democracy and the financial crisis. American Behavioral Scientist, 58(12), 1517–1541. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764214534666.

Della Porta, D., & Mény, Y. (Eds.). (1997). Democracy and corruption in Europe. London: Pinter.

Dincer, O., & Johnston, M. (2015). Measuring illegal and legal corruption in American states: Some results from the Safra Center corruption in America Survey. Edmond J. Safra Research Lab Working Papers, 58, 1–41. http://ssrn.com/abstract=2579300.

Dowley, K. M., & Silver, B. D. (2002). Social capital, ethnicity and support for democracy in the post-communist states. Europe-Asia Studies, 54(4), 505–527. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668130220139145.

Dungan, J., Waytz, A., & Young, L. (2014). Corruption in the context of moral trade-offs. Journal of Interdisciplinary Economics, 26(1–2), 97–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/0260107914540832.

Ehin, P. (2007). Political support in the baltic states, 1993–2004. Journal of Baltic Studies, 38(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/01629770701223486.

Ekici, T., & Koydemir, S. (2014). Social capital, government and democracy satisfaction, and happiness in Turkey: A comparison of surveys in 1999 and 2008. Social Indicators Research, 118(3), 1031–1053. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0464-y.

European Commission. (2013). Standard Eurobarometer no. 79. http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/eb/eb79/eb79_publ_en.pdf. Accessed 2 July 2016.

European Commission. (2014). Special Eurobarometer no. 397. http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_397_en.pdf. Accessed 2 July 2016.

European Commission. (2017a). Eurobarometer 79.3 (2013) (TNS opinion, Ed.). ZA5689 data file version 2.0.0. Brussels: GESIS Data Archive. https://doi.org/10.4232/1.12718.

European Commission. (2017b). Eurobarometer 79.3 (2013)—Variable report/codebook ZA5689. Brussels: GESIS Data Archive. https://doi.org/10.4232/1.12718.

Fackler, T., & Lin, T. (1995). Political corruption and presidential elections, 1929–1992. The Journal of Politics, 57(4), 971–993. https://doi.org/10.2307/2960398.

FFMS/Francisco Manuel dos Santos Foundation. (2016a). GDP per capita (PPS). PORDATA database. http://www.pordata.pt/en/DB/Europe/Search+Environment/Table/5701020. Accessed 26 December 2016.

FFMS/Francisco Manuel dos Santos Foundation. (2016b). Unemployment rate, aged 15 to 74. PORDATA database. http://www.pordata.pt/en/DB/Europe/Search+Environment/Table/5701021. Accessed 26 December 2016.

Foster, C., & Frieden, J. (2017). Crisis of trust: Socio-economic determinants of Europeans’ confidence in government. European Union Politics. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116517723499.

Friedrich, C. J. (1966). Political pathology. The Political Quarterly, 37(1), 70–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-923X.1966.tb00184.x.

Friedrich, C. J. (2002). Corruption concepts in historical perspective. In A. J. Heidenheimer & M. Johnston (Eds.), Political corruption: Concepts and contexts (pp. 15–23). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books.

Friedrichsen, J., & Zahn, P. (2010). The macroeconomy and individuals’ support for democracy. In 19th workshop on political economy, CWPE 1104.

Galtung, F. (2006). Measuring the immeasurable: Boundaries and functions of (macro) corruption indices. In C. Sampford, A. Shacklock, C. Connors, & F. Galtung (Eds.), Measuring corruption (pp. 101–130). Hampshire: Ashgate.

Gardiner, J. A. (1992). Defining corruption. Corruption and Reform, 7(2), 111–124.

Harteveld, E., Van der Meer, T., & De Vries, C. E. (2013). In Europe we trust? Exploring three logics of trust in the European Union. European Union Politics, 14(4), 542–565. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116513491018.

Heidenheimer, A. J. (2002). Perspectives on the perception of corruption. In A. J. Heidenheimer & M. Johnston (Eds.), Political corruption: Concepts and contexts (pp. 141–154). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Hellman, J., & Schankerman, M. (2000). Intervention, corruption and capture: The nexus between enterprises and the state. The Economics of Transition, 8(3), 545–576. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0351.00055.

Hobolt, S. B. (2012). Citizen satisfaction with democracy in the European Union. Journal of Common Market Studies, 50(S1), 88–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2011.02229.x.

Holmberg, S., & Rothstein, B. (Eds.). (2012). Good government: The relevance of political science. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

Johnston, M. (1996). The search for definitions: The vitality of politics and the issue of corruption. International Social Science Journal, 48(3), 321–335. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2451.00035.

Johnston, M. (2005). Syndromes of corruption: Wealth, power, and democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jos, P. H. (1993). Empirical corruption research: Beside the (moral) point? Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 3(3), 359–375.

Karklins, R. (2002). Typology of post-communist corruption. Problems of Post-Communism, 49(4), 22–32.

Kaufmann, D., & Kraay, A. (2016). WGI full dataset. The Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) project. www.govindicators.org. Accessed 12 February 2017.

Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Mastruzzi, M. (2009). Governance matters VIII: Aggregate and individual governance indicators. Policy research working paper 4978. Washington, DC: World Bank. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/598851468149673121/Governance-matters-VIII-aggregate-and-individual-governance-indicators-1996-2008.

Kaufmann, D., & Vicente, P. C. (2011). Legal corruption. Economics and Politics, 23(2), 195–219. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0343.2010.00377.x.

Kestilä-Kekkonen, E., & Söderlund, P. (2017). Is it all about the economy? Government fractionalization, economic performance and satisfaction with democracy across Europe, 2002–13. Government and Opposition, 52(1), 100–130. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2015.22.

Kjellberg, F. (1992). Corruption as an analytical problem: Some notes on research in public corruption. Indian Journal of Administrative Science, 3(1–2), 195–221.

Klašnja, M., & Tucker, J. A. (2013). The economy, corruption, and the vote: Evidence from experiments in Sweden and Moldova. Electoral Studies, 32(3), 536–543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2013.05.007.

Klašnja, M., Tucker, J. A., & Deegan-Krause, K. (2014). Pocketbook vs. sociotropic corruption voting. British Journal of Political Science, 46(1), 67–94. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123414000088.

Lambsdorff, J. G. (2006). Causes and consequences of corruption. In S. Rose-Ackerman (Ed.), International handbook on the economics of corruption (pp. 3–51). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

Lange, D., & Onken, H. (2013). Political socialization, civic consciousness and political interest of young adults. In M. Print & D. Lange (Eds.), Civic education and competences for engaging citizens in democracies. Civic and political education (Vol. 3, pp. 65–76). Rotterdam: SensePublishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6209-172-6_6.

Ledeneva, A. V. (1998). Russia’s economy of favours: Blat, networking and informal exchange. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Leiter, D., & Clark, M. (2015). Valence and satisfaction with democracy: A cross-national analysis of nine Western European democracies. European Journal of Political Research, 54(3), 543–562. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12088.

Lessig, L. (2013). Foreword: ‘Institutional corruption’ defined. Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics, 41(3), 553–555.

Lewis-Beck, M. S. (1988). Economics and elections: The major western democracies. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Light, D. W. (2013). Strengthening the theory of institutional corruptions: Broadening, clarifying, and measuring. Edmond J. Safra Research Lab Working Papers, 2, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2236391.

Linde, J. (2012). Why feed the hand that bites you? Perceptions of procedural fairness and system support in post-communist democracies. European Journal of Political Research, 51(3), 410–434. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2011.02005.x.

Maciel, G. G. (2016). Legal corruption: A way to explain citizens’ perceptions about the relevance of corruption. Master’s thesis. Aveiro: University of Aveiro.

Magalhães, P. C. (2014). Government effectiveness and support for democracy. European Journal of Political Research, 53(1), 77–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12024.

Magalhães, P. C. (2016). Economic evaluations, procedural fairness, and satisfaction with democracy. Political Research Quarterly, 69(3), 522–534. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912916652238.

Meehl, P. E. (1977). The selfish voter paradox and the thrown-away vote argument. The American Political Science Review, 71(1), 11–30. https://doi.org/10.2307/1956951.

Memoli, V. (2016). Unconventional participation in time of crisis: How ideology shapes citizens’ political actions. Partecipazione e Conflitto, 9(1), 127–151. https://doi.org/10.1285/i20356609v9i1p127.

Memoli, V., & Pellegata, A. (2013). Electoral systems, corruption and satisfaction with democracy. In XXVII annual conference of the Italian political science (pp. 1–40), Florence, Italy.

Mensah, Y. M. (2014). An analysis of the effect of culture and religion on perceived corruption in a global context. Journal of Business Ethics, 121(2), 255–282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1696-0.

Miller, W. L., Grødeland, Å. B., & Koshechkina, T. Y. (2001). A culture of corruption? Coping with government in post-communist Europe. Budapest: Central European University Press.

Mishler, W., & Rose, R. (2001). Political support for incomplete democracies: Realist vs. idealist theories and measures. International Political Science Review, 22(4), 303–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512101022004002.

Morlino, L. (2009). Legitimacy and the quality of democracy. International Social Science Journal, 60(196), 211–222.

Morris, S. D., & Klesner, J. L. (2010). Corruption and trust: Theoretical considerations and evidence from Mexico. Comparative Political Studies, 43(10), 1258–1285. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414010369072.

Newhouse, M. E. (2014). Institutional corruption: A fiduciary theory. Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy, 23(3), 553–594. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2335619.

Newton, K. (2006). Political support: Social capital, civil society and political and economic performance. Political Studies, 54(4), 846–864. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2006.00634.x.

Norpoth, H. (1996). The Economy. In L. LeDuc, R. G. Niemi, & P. Norris (Eds.), Comparing democracies: Elections and voting in global perspective (pp. 299–318). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Nye, J. S. (1967). Corruption and political development: A cost- benefit analysis. The American Political Science Review, 61(2), 417–427.

O’Donnell, G. A. (2007). The perpetual crises of democracy. Journal of Democracy, 18(1), 5–11.

Pellegata, A., & Memoli, V. (2016). Can corruption erode confidence in political institutions among European countries? Comparing the effects of different measures of perceived corruption. Social Indicators Research, 128(1), 391–412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1036-0.

Philp, M. (1997a). Defining political corruption. In P. Heywood (Ed.), Political corruption (pp. 20–46). Oxford: Blackwell.

Philp, M. (1997b). Defining political corruption. Political Studies, 45(3), 436–462.

Philp, M. (2001). Access, accountability and authority: Corruption and the democratic process. Crime, Law and Social Change, 36(4), 357–377. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012075027147.

Polavieja, J. (2013). Economic crisis, political legitimacy, and social cohesion. In D. Gallie (Ed.), Economic crisis, quality of work and social integration: The European experience (pp. 256–278). Oxford: Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199664719.001.0001/acprof-9780199664719-chapter-10.

Quaranta, M., & Martini, S. (2017). Easy come, easy go? Economic performance and satisfaction with democracy in southern Europe in the last three decades. Social Indicators Research, 131(2), 659–680. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1270-0.

Rock, M. T. (2009). Corruption and democracy. Journal of Development Studies, 45(1), 55–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380802468579.

Rogow, A. A., & Lasswell, H. D. (1977). Power, corruption, and rectitude. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Rothstein, B. (2009). Preventing markets from self-destruction: The quality of government factor. QoG working paper series (Vol. 2). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1328819.

Rothstein, B. (2011). The quality of government: Corruption, social trust, and inequality in international perspective. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Rothstein, B., & Teorell, J. (2008). What is quality of government? A theory of impartial government institutions. Governance, 21(2), 165–190. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0491.2008.00391.x.

Sanches, E. R., & Gorbunova, E. (2016). Portuguese citizens’ support for democracy: 40 years after the carnation revolution. South European Society and Politics, 21(2), 211–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2015.1130680.

Schneider, F. (2015). Size and development of the shadow economy of 31 European and 5 other OECD countries from 2003 to 2014: Different developments? Journal of Self-Governance and Management Economics, 3(4), 7–29. http://www.econ.jku.at/schneider.

Seligson, M. A. (2002). The impact of corruption on regime legitimacy: A comparative study of four Latin American countries. Journal of Politics, 64(2), 408–433. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2508.00132.

Stadelmann-Steffen, I., & Vatter, A. (2012). Does satisfaction with democracy really increase happiness? Direct democracy and individual satisfaction in Switzerland. Political Behavior, 34(3), 535–559. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-011-9164-y.

Stockemer, D. (2013). Corruption and turnout in presidential elections: A macro-level quantitative analysis. Politics and Policy, 41(2), 189–212. https://doi.org/10.1111/polp.12012.

Stockemer, D., & Sundström, A. (2013). Corruption and citizens’ satisfaction with democracy in Europe: What is the empirical linkage? Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft, 7(S1), 137–157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12286-013-0168-3.

Teixeira, C. P., Tsatsanis, E., & Belchior, A. M. (2014). Support for democracy in times of crisis: Diffuse and specific regime support in Portugal and Greece. South European Society and Politics, 19(4), 501–518. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2014.975770.

Thompson, D. F. (2013). Two concepts of corruption. Edmond J. Safra Research Lab Working Papers, 16, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2304419.

Transparency International. (2016). What is corruption? http://www.transparency.org/what-is-corruption/. Accessed 16 March 2016.

Treisman, D. (2000). The causes of corruption: A cross-national study. Journal of Public Economics, 76(3), 399–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2727(99)00092-4.

Treisman, D. (2007). What have we learned about the causes of corruption from ten years of cross-national empirical research? Annual Review of Political Science, 10(1), 211–244. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.10.081205.095418.

Van Erkel, P. F. A., & Van Der Meer, T. W. G. (2016). Macroeconomic performance, political trust and the great recession: A multilevel analysis of the effects of within-country fluctuations in macroeconomic performance on political trust in 15 EU countries, 1999–2011. European Journal of Political Research, 55(1), 177–197. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12115.

Vigoda-Gadot, E., Shoham, A., & Vashdi, D. R. (2010). Bridging bureaucracy and democracy in Europe: A comparative study of perceived managerial excellence, satisfaction with public services, and trust in governance. European Union Politics, 11(2), 289–308. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116510363657.

Villoria, M., van Ryzin, G. G., & Lavena, C. F. (2012). Social and political consequences of administrative corruption: A study of public perceptions in Spain. Public Administration Review, 73(1), 85–94. https://doi.org/10.111/j.1540-6210.2012.02613.x.

Wagner, A. F., Schneider, F., & Halla, M. (2009). The quality of institutions and satisfaction with democracy in Western Europe—A panel analysis. European Journal of Political Economy, 25(1), 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2008.08.001.

Waldron-Moore, P. (1999). Eastern Europe at the crossroads of democratic transition: Evaluating support for democratic institutions, satisfaction with democratic government, and consolidation of democratic regimes. Comparative Political Studies, 32(1), 32–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414099032001002.

Warren, M. E. (2004). What does corruption mean in a democracy? American Journal of Political Science, 48(2), 328–343. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0092-5853.2004.00073.x.

Weber, M. (1995 [1922]). Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft. Grundriss der verstehenden Soziologie (posthumous publication). In M. B. da Cruz (Trans.), Teorias Sociológicas (Vol. 1, pp. 727–728). Lisbon: Edições Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian.

Weßels, B. (2015). Political culture, political satisfaction and the rollback of democracy. Global Policy, 6(1), 93–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12232.

World Bank. (1997). Helping countries combat corruption. http://www1.worldbank.org/publicsector/anticorrupt/corruptn/corrptn.pdf. Accessed 5 April 2015.

Zechmeister, E. J., & Zizumbo-Colunga, D. (2013). The varying political toll of concerns about corruption in good versus bad economic times. Comparative Political Studies, 46(10), 1190–1218. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414012472468.

Zmerli, S., & Newton, K. (2008). Social trust and attitudes toward democracy. Public Opinion Quarterly, 72(4), 706–724. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfn054.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the reviewers and in particular to Pedro Magalhães, senior research fellow at the Institute of Social Sciences of the University of Lisbon (ICS-UL), for their detailed and helpful comments. Needless to say, the authors are solely responsible for the contents and any errors and omissions that may be detected in the article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The opinions expressed in this article are the Gustavo Gouvêa Maciel’s own and do not reflect the official view of FUNAG.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Maciel, G.G., de Sousa, L. Legal Corruption and Dissatisfaction with Democracy in the European Union. Soc Indic Res 140, 653–674 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1779-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1779-x