Abstract

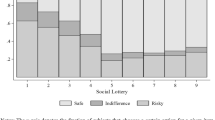

Individuals take decisions on behalf of others in many different contexts. In this paper, we focus on lotteries with negative expected value and study if (and how) risky choices made on behalf of another person differ i) compared to decisions which do not affect anyone else, and ii) depending on the social distance between who makes the decision and who is affected by it. Our results show that social distance (i.e., whether the person affected by one’s decision is an unknown stranger or a friend) is an important determinant when people decide on behalf of others. Moreover, when deciding on behalf of a friend rather than only for themselves or a stranger, average individual behavior is closer to expected value maximization, exhibiting less risk taking. These findings suggest that responsibility for others’ outcome and the empathy gap affect the decision making process, particularly when the social distance is shortened. The results are robust to different feedback frequencies. Controlling for order effects shows that experiencing a decrease in social distance is crucial in activating this mechanism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For the sake of brevity, the terms “risky choice” and “lottery” are used interchangeably in the paper when referring to lotteries with negative expected value.

People spend a consistent amount of money to play lotteries and commercial gambling (Kearney 2005; Clotfelter and Cook 1990). Some people enter self-employment and inventive activities, that, on average, have negative returns and high variance (Åstebro 2003). Households overinvest in the most skewed assets, like stocks with higher volatility and large positive skewness (Kumar 2009).

Only a few works have theoretically modeled these situations (see, e.g. Trautmann 2009).

Subjects are informed that the three decisions contained in each block are identical. More details can be found in the Instructions reproduced in English in the online Appendix B.

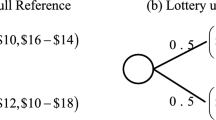

The two lotteries give the same (negative) expected value, but differ both in their variance (V ar(A) > V ar(B)) and in the fact that money put on the lottery can be totally or partially lost in case a negative outcome realizes.

Specifically, the decision situation for the active participant was described as follows: “Now we are about to start the first (second/third/fourth) block of risky choices. Each block contains 3 risky choices. In each period of a block, you will face the same project and you have to make your risky choice for the passive participant.” Then, on the decision screen the active participant was required to do the following: “Please indicate how many ECUs of the PASSIVE participant you want to invest in Project 1. The ECUs that you don’t invest will be accumulated in the total balance of the PASSIVE participant.” Finally, in the instructions the following was specified: “If this part, i.e., part 2, is selected, then: 1) the passive participant matched with you will earn the sum of the earnings obtained as a consequence of your risky choices in each of the 12 periods of part 2. 2) You will earn the same amount of ECUs he earns.” See the online Appendix B for more details.

The name, surname, and e-mail address of the friend had to be communicated via email to the experimenters at least 24 hours before the scheduled sessions in order to verify that s/he had not participated in another session of the same experiment before.

While the active participants were making their choices, we asked the passive participants to take hypothetical decisions identical to the ones faced by the active participants but irrelevant for the determination of their final payoff as passive participants. Details about the hypothetical decisions taken by the passive participants can be obtained by the authors upon request.

The only exception was that, while in Jena the experiment was conducted in German, in Copenhagen, following the norm of the laboratory, the experiment was conducted in English and participants were mostly exchange students visiting Copenhagen University for one or two semesters during their master’s or bachelor’s program. We thank the Editorial Board and an anonymous referee for advising on this part of the analysis.

As our main results concerning social distance do not differ varying the feedback frequency, we limit the additional sessions to the IFT.

In June 2016 10 DKK corresponded to 1.34 Euros.

Unless not differently specified, all tests reported are two-sided.

The two measures are highly correlated: participants who choose more often not to put any ECUs on the lottery also tend to put a lower amount of ECUs the times they put something (according to a set of Spearman correlation measurements: FFT + IFT: ρ = − 0.602, p = 0.000; FFT: ρ=-0.569, p = 0.000; FFT: ρ=-0.588, p = 0.000). This suggests that choosing to put some ECUs on the lottery few times but with a very high amount of ECUs seems not to be a very common behavior in our data.

For the participants, it is common knowledge that only one of the three experimental parts will be randomly selected at the end of the experiment to determine the experimental earnings. This feature of the experimental design aims at reducing the influence of earnings from an earlier part on the behavior of the subsequent one. Order effects are discussed in Section 7.

Both Results 1.a and 1.b hold when separately considering Lottery A and Lottery B; see the online Appendix A.

Interestingly, FFT induces a behavior more closely related to expected value maximization. In contrast, Haisley et al. (2008) document the existence of a reverse myopic effect for lottery tickets with very small probability of a large gain.

We choose a Tobit model since our dependent variable, i.e. the amount of ECUs put on the lottery, is censored.

The general risk question of the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP) requests that participants give an assessment of their own general willingness to take risks on a 0-10 scale. Participants were also asked to indicate an anonymous stranger’s and their friends’ general willingness to take risks. On the behavioral validity of this measure in economic experiments see Dohmen et al. (2011).

Participants could indicate their monthly income after tax (including study loan and any transfer payments) by indicating 8 income classes, from class 1: 0-500 Euros per month, to class 8: more than 2001 Euros per month, with intervals of 250 Euros each, etc: 501-750; 751-1000, etc.

In the ST and FT we pool the data from seq. 1 and seq. 3 since differences are not significant. In the FT for i) the average investment (z = 0.820, p = 0.412) and ii) the average number of safe choices (z = 1.062, p = 0.288). In the ST: average investment (z = 1.028, p = 0.304) and average number of safe choices (z = 0.748, p = 0.454). Similarly, we pool the data for seq. 2 and seq. 4. In the FT i) average investment (z = 0.559, p = 0.576) and ii) average number of safe choices (z = 0.482, p = 0.630). In the ST: average investment (z = 0.629, p = 0.529) and average number of safe choices (z = 0.629, p = 0.529).

When participants experience an increase in SD (seq. 2 and 4) we find that the average investment is not significantly different in the ST and FT treatment (WSR test: z = 1.130, p = 0.259), while the number of safe choices is significantly higher in ST compared to FT (WSR test: z = 2.347, p = 0.019).

This can be explained by the fact that many participants are exchange students visiting Copenhagen for 6-12 months. Specifically, participants in Copenhagen are significantly less likely to consider the friend in the lab as a close friend compared to the participants in Jena (65.66% vs 79.03%, Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.010) and are more likely to know each other for less than one year compared to Jena (48.49% vs 37.10%, Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.002).

If we focus on the average number of safe choices, in all sequences the average proportion of safe choices is not different when comparing ST and FT irrespectively from having a close friend or not in the lab.

Compared to model 5, sign is reversed for age as well, which is negative and significant. The coefficients for the variable income and extraversion do not achieve significance, while other effects are unchanged.

When focusing on the risky choices in the OT, ST and FT treatment we do not find significant differences comparing seq. 1 vs 2 and seq. 3 vs 4 both when considering i) the average amount of ECUs and ii) the average number of safe choices. See the Online Appendix for detailed results.

In other contexts, learning processes can lead to increased consistency in choices, implying a reduced variance, whereas fatigue effects will have the opposite implication. Comparing the variance of the choices, we can also exclude that fatigue, interpreted as increased randomness of the decision, can explain our results: the variance in seq. 1 and 2 is equal to 596.453, while the variance in seq. 3 and 4 is equal to 500.817.

References

Abdellaoui, M., L’Haridon, O., Paraschiv, C. (2013). Individual vs. couple behavior: An experimental investigation of risk preferences. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 75(2), 175–191.

Andersson, O., Holm, H. J., Tyran, J. R., Wengström, E. (2014). Deciding for others reduces loss aversion. Management Science, 62(1), 29–36.

Åstebro, T. (2003). The return to independent invention: Evidence of unrealistic optimism, risk seeking or skewness loving? The Economic Journal, 113(484), 226–239.

Ball, S., & Eckel, C. C. (1998). The economic value of status. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 24(4), 495–514.

Bellemare, C., Sebald, A., Suetens, S. (2017). Heterogeneous guilt sensitivities and incentive effects. Experimental Economics.

Bolton, G. E., & Ockenfels, A. (2010). Betrayal aversion: Evidence from Brazil, China, Oman, Switzerland, Turkey, and the United States: Comment. American Economic Review, 100(1), 628–33.

Brock, J. M., Lange, A., Ozbay, E. Y. (2013). Dictating the risk: Experimental evidence on giving in risky environments. American Economic Review, 103(1), 415–437.

Carlsson, F., Daruvala, D., Jaldell, H. (2012). Do administrators have the same priorities for risk reductions as the general public? Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 45(1), 79–95.

Cettolin, E., & Tausch, F. (2015). Risk taking and risk sharing: Does responsibility matter? Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 50(3), 229–248.

Chakravarty, S., Harrison, G. W., Haruvy, E. E., Rutström, E. E. (2011). Are you risk averse over other people’s money? Southern Economic Journal, 77(4), 901–913.

Charness, G., & Dufwenberg, M. (2006). Promises and partnership. Econometrica, 74(6), 1579–1601.

Charness, G., & Gneezy, U. (2008). What’s in a name? Anonymity and social distance in dictator and ultimatum games. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 68(1), 29–35.

Charness, G., & Gneezy, U. (2010). Portfolio choice and risk attitudes: An experiment. Economic Inquiry, 48(1), 133–146.

Charness, G., & Jackson, M. O. (2009). The role of responsibility in strategic risk-taking. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 69(3), 241–247.

Charness, G., & Rabin, M. (2002). Understanding social preferences with simple tests. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(3), 817–869.

Charness, G., Haruvy, E., Sonsino, D. (2007). Social distance and reciprocity: An internet experiment. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 63(1), 88–103.

Charness, G., Karni, E., Levin, D. (2013). Ambiguity attitudes and social interactions: An experimental investigation. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 46(1), 1–25.

Clotfelter, C. T., & Cook, P. J. (1990). On the economics of state lotteries. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 4(4), 105–119.

Croson, R., & Gneezy, U. (2009). Gender differences in preferences. Journal of Economic Literature, 47(2), 448–474.

Daruvala, D. (2007). Gender, risk and stereotypes. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 35(3), 265–283.

Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., Sunde, U., Schupp, J., Wagner, G. G. (2011). Individual risk attitudes: Measurement, determinants, and behavioral consequences. Journal of the European Economic Association, 9(3), 522–550.

Eriksen, K. W., & Kvaloy, O. (2010). Myopic investment management. Review of Finance, 14(3), 521–542.

Faro, D., & Rottenstreich, Y. (2006). Affect, empathy, and regressive mispredictions of others’ preferences under risk. Management Science, 52(4), 529–541.

Fehr, E., & Schmidt, K. M. (1999). A theory of fairness, competition, and cooperation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(3), 817–868.

Fershtman, C., & Gneezy, U. (2001). Strategic delegation: An experiment. RAND Journal of Economics, 32(2), 352–68.

Fischbacher, U. (2007). Z-tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Experimental Economics, 10(2), 171–178.

Frey, B. S., & Bohnet, I. (1999). Social distance and other-regarding behavior in dictator games: Comment. American Economic Review, 89(1), 335–339.

Frohlich, N., & Oppenheimer, J. (1998). Some consequences of e-mail vs. face-to-face communication in experiment. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 35(3), 389–403.

Glaeser, E. L., Laibson, D. I., Scheinkman, J. A., Soutter, C. L. (2000). Measuring trust. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(3), 811–846.

Gneezy, U., & Potters, J. (1997). An experiment on risk taking and evaluation periods. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(2), 631–45.

Greiner, B. (2004). The online recruitment system orsee - A guide for the organization of experiments in economics. Tech. rep.

Haisley, E., Mostafa, R., Loewenstein, G. (2008). Myopic risk-seeking: The impact of narrow decision bracketing on lottery play. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 37(1), 57–75.

Hoffman, E., McCabe, K., Smith, V. L. (1996). Social distance and other-regarding behavior in dictator games. American Economic Review, 86(3), 653–660.

Holm, H. J. (2000). Gender-based focal points. Games and Economic Behavior, 32(2), 292–314.

Hsee, C., & Weber, E. (1997). A fundamental prediction error: Self–others discrepancies in risk preference. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 126 (1), 45–53.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–291.

Kearney, M. S. (2005). State lotteries and consumer behavior. Journal of Public Economics, 89(11-12), 2269–2299.

Kumar, A. (2009). Who gambles in the stock market? Journal of Finance, 64 (4), 1889–1933.

Lamm, H., Trommsdorff, G., Rost-Schaude, E. (1972). Self-image, perception of peers’ risk acceptance and risky shift. European Journal of Social Psychology, 2 (3), 255–272.

Li, Z., Rohde, K. I., Wakker, P. P. (2017). Improving one’s choices by putting oneself in others’ shoes–An experimental analysis. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 54(1), 1–13.

Linde, J., & Sonnemans, J. (2012). Social comparison and risky choices. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 44(1), 45–72.

Loewenstein, G. (1996). Out of control: Visceral influences on behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 65(3), 272–292.

Loewenstein, G. F., Hsee, C. K., Weber, E. U., Welch, N. (2001). Risk as feelings. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 267–286.

Nicholson, N., Soane, E., Fenton-O’Creevy, M., Willman, P. (2005). Personality and domain-specific risk taking. Journal of Risk Research, 8(2), 157–176.

Pahlke, J., Strasser, S., Vieider, F. M. (2015). Responsibility effects in decision making under risk. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 51(2), 125–146.

Rankin, F. W. (2006). Requests and social distance in dictator games. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 60(1), 27–36.

Rohde, I., & Rohde, K. (2011). Risk attitudes in a social context. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 43(3), 205–225.

Rubaltelli, E., Agnoli, S., Rancan, M., Pozzoli, T. (2015). Emotional intelligence and risk taking in investment decision-making. Tech. rep.

Shupp, R., & Williams, A. (2008). Risk preference differentials of small groups and individuals. Economic Journal, 118(525), 258–283.

Stone, E. R., & Allgaier, L. (2008). A social values analysis of self–other differences in decision making involving risk. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 30(2), 114–129.

Sutter, M. (2007). Are teams prone to myopic loss aversion? An experimental study on individual versus team investment behavior. Economics Letters, 97(2), 128–132.

Sutter, M. (2009). Individual behavior and group membership: Comment. American Economic Review, 99(5), 2247–2257.

Tajfel, G. E., & Katok, E. (1970). Experiments in intergroup discrimination. Scientific American, 223(5), 96–102.

Telle, N. T., Senior, C., Butler, M. (2011). Trait emotional intelligence facilitates responses to a social gambling task. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(4), 523–526.

Thaler, R.H. (1997). The effect of myopia and loss aversion on risk taking: An experimental test. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(2), 647–661.

Thaler, R. (1985). Mental accounting and consumer choice. Marketing Science, 4(3), 199–214.

Trautmann, S. T. (2009). A tractable model of process fairness under risk. Journal of Economic Psychology, 30(5), 803–813.

Vestewig, R. E. (1977). Extraversion and risk preference in portfolio theory. The Journal of Psychology, 97(2), 237–245.

Viscusi, W. K., Phillips, O. R., Kroll, S. (2011). Risky investment decisions: How are individuals influenced by their groups? Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 43 (2), 81–106.

Ziegler, F. V., & Tunney, R. J. (2012). Decisions for others become less impulsive the further away they are on the family tree. PLOS ONE, 7(11), 1–5.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Editorial Board of the Journal and two anonymous referees for very useful and constructive comments. We also thank Dominique Cappelletti, Paolo Crosetto, Antonio Filippin, Alexia Gaudel, Paola Manzini and Matthias Sutter for useful discussion and precious advice, and Dvin Galstian Pour for excellent research assistance. All remaining errors are ours. Montinari gratefully acknowledges the Max Planck Institute (Jena, Germany) and Handelsbanken (Stockholm, Sweden) for funding the data collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The opinions expressed are those of the authors only and should not be considered as representative of the European Commission’s official position.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Montinari, N., Rancan, M. Risk taking on behalf of others: The role of social distance. J Risk Uncertain 57, 81–109 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-018-9286-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-018-9286-2

Keywords

- Risk seeking

- Social distance

- Friends

- Responsibility

- Other-regarding preferences

- Risky choices

- Myopic loss aversion