Abstract

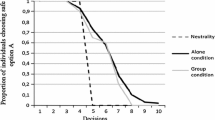

We investigate the effect of group versus individual decision-making in the context of risky investment decisions in which all subjects are fully informed of the probabilities and payoffs. Although there is full information, the lottery choices pose cognitive challenges so that people may not be sure of their expected utility-maximizing choice. Making such decisions in a group context provides real-time information in which group members can observe others’ choices and revise their own decisions. Our experimental results show that simply observing what others in the group do has a significant impact on behavior. Coupling real-time information with group decisions based on the median value, i.e., majority rule, makes the median investment choice focal, leading people with low values to increase investments and those with high values to decrease investments. Group decisions based on the minimum investment amount produce more asymmetric effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We create this type of choice environment as one with high potential for individual and/or group decisions to stray from a focus on marginal benefits and costs. For different reasons as described below, individual and group decisions can be very different in this setting.

The information cascades analyzed by Bikhchandani et al. (1992, 1998) and the herding effects analyzed by Banerjee (1992) are defined similarly. In each case, individuals find it optimal to follow the actions of others rather than relying on their private information. Anderson and Holt (1997) present experimental evidence on these effects, while Daughety and Reinganum (1999) examine herding effects for judicial decisions. Rook (2006) provides a general review.

To the extent that there is learning, it is with respect to others’ decisions and one’s own preferences. For our RTI environments, we suggest that behavioral changes are attributable to noisy individual preferences coupled with information about welfare-maximizing choices provided by RTI. Note the difference between our paper and research on the “wisdom of crowds.” Here there is no right or wrong answer, and uncertainty exists only with regard to preferences and to the optimal strategy, while the wisdom of crowds refers to the (mathematical) fact that groups on the aggregate often come up with better answers to factual questions than individuals. In a recent paper, Lorenz et al. (2011) found experimental evidence that social influence can counteract the wisdom of crowds effect and can lead a group to wrong answers.

Ambrus et al. (2009) conduct experimental tests demonstrating that evidence of risky shifts in mean group decisions may provide a misleading perspective on the shifts in individual decisions. Their analysis of experimental lottery choices did not indicate any risky shift for individuals relative to the median.

While one might not expect the group decision rule to alter individual choices, in an experiment with a very different structure than ours, Guarnaschelli et al. (2000) found experimental evidence of strategic, insincere behavior with both majority rule and a unanimity group decision rule.

Fischhoff (1983) discusses the importance of decision frames and the difficulties that arise in predicting the effect of the frames ex ante rather than offering ex post rationalizations of framing effects that take advantage of hindsight.

The potential influence on group contexts as well as the salience of the group environment has been examined in experimental studies by Blinder and Morgan (2005), Cooper and Kagel (2005), Goette et al. (2006), Charness et al. (2007), Tan and Bolle (2007), Sutter (2007, 2009) and Hargreaves-Heap and Zizzo (2009). Reviews of the related psychology literature appear in Brown (1986), Kerr et al. (1996), and Aronson et al. (2005).

In another study with risky choices—which are presented either in abstract terms or as “investments”—Eckel and Grossman (2008a) found “little evidence that the framing of the gamble choice affects subjects’ choices overall” (p.7).

Results in Blinder and Morgan (2005) indicate that the speed of decision making is similar for majority rule and unanimity.

There is an emerging literature on noise exhibited using different elicitation procedures, such as the recent contributions by Anderson and Mellor (2009) and by Hey et al. (2009). Noise could arise due to the elicitation procedure or because of unstable preferences. For our situation, we hypothesize that one potential source of noise is error in making complicated decisions involving lotteries.

The sample variance of the difference is \( s_D^2 = s_{\left( {x - y} \right)}^2 = s_x^2 + s_y^2 - 2{s_{xy}}. \) \( s_{\overline D }^2 = s_D^2/n. \) \( \overline D = \overline X - \overline Y . \) The test statistic is \( \overline D /{s_{\overline D }}. \) Number of observations is 24 unless otherwise noted. A normal table is used to decide significance.

Estimates for the subsample of 118 consistent respondents are very similar as one might expect given the lack of statistical significance for the variable pertaining to inconsistent responses.

We did not detect any gender effect on the lottery choices in Part I. For a review of experimental studies of gender differences in risk aversion, see Eckel and Grossman (2008b).

Some of the effect of risk aversion may be captured already in the individual expenditure variable. Omission of that variable from the various regressions sometimes boosts the statistical significance of the CRRA variable, leading to t statistics above 1.0 but falling short of the usual test levels for statistical significance.

Including the measure of whether the person won in the earlier group lottery captures the outcome which, unlike the normal order case, depends on the group decision and not necessarily on the individual decision.

There is mixed evidence over whether males and females exhibit different levels of risk aversion; see for example Schubert et al. (1999). Charness and Gneezy (2007) present evidence showing that when it comes to making investment decisions, women are more risk-averse than men. Gneezy et al. (2003) and Niederle and Vesterlund (2007) raise the argument “that males and females preferences are affected differently by changes in the institution…” (Gneezy et al. 2003, p.1052). The competitiveness of the decision environment, in particular, causes men and women to behave differently. It is possible in this treatment that after observing the choices of others, females gained the confidence to take more risk, an interpretation consistent with results in Healy and Pate (2011), who find that a “gender competition gap” is decreased in team settings.

Similarly, empirical simulations of group decisions generally are based on random draws of individual choices to construct a synthetic group. This approach has been used in several law and economics studies of jury behavior.

Our subjects seem to be slightly less risk-averse than subjects in other papers who used the Holt-Laury mechanism: for example, in Holt and Laury (2002) itself, 8% were risk-loving, 26% risk-neutral and 66% risk-averse, while in Anderson and Mellor (2009) and Lusk and Coble (2005) those numbers were 5%, 21% and 75%, and 12%, 24% and 64%, respectively.

References

Ambrus, A., Greiner, B., & Pathak, P. (2009). Group versus individual decision-making: Is there a shift? Institute for Advanced Study, School of Social Science Economics Working Paper 0091.

Anderson, L. R., & Holt, C. A. (1997). Information cascades in the laboratory. American Economic Review, 87(5), 847–862.

Anderson, L. R., & Mellor, J. M. (2009). Are risk preferences stable? Comparing an experimental measure with a validated survey-based measure. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 39(2), 137–160.

Aronson, E., Wilson, T. D., & Akert, R. M. (2005). Social psychology (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River: Pearson.

Banerjee, A. V. (1992). A simple model of herd behavior. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107(3), 797–817.

Bikhchandani, S., Hirshleifer, D., & Welch, I. (1992). A theory of fads, fashion, custom, and cultural change as informational cascades. Journal of Political Economy, 100(5), 992–1026.

Bikhchandani, S., Hirshleifer, D., & Welch, I. (1998). Learning from the behavior of others: conformity, fads, and informational cascades. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 12(3), 151–170.

Blinder, A. S., & Morgan, J. (2005). Are two heads better than one? Monetary policy by committee. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, 37(5), 789–811.

Brown, R. (1986). Social psychology: The second edition. New York: Free Press.

Charness, G., & Gneezy, U. (2007). Strong evidence for gender differences in investment. SSRN Working Paper.

Charness, G., Rigotti, L., & Rustichini, A. (2007). Individual behavior and group membership. American Economic Review, 97(4), 1340–1352.

Cooper, D. J., & Kagel, J. H. (2005). Are two heads better than one? Team versus individual play in signaling games. American Economic Review, 95(3), 477–509.

Daughety, A. F., & Reinganum, J. F. (1999). Stampede to judgment: persuasive influence and herding behavior by courts. American Law and Economics Review, 1(1), 158–189.

Eckel, C. C., & Grossman, P. J. (2008a). Forecasting risk attitudes: an experimental study using actual and forecast gamble choices. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 68(1), 1–17.

Eckel, C. C., & Grossman, P. J. (2008b). Men, women and risk aversion: Experimental results. Working paper. Forthcoming in C. Plott and V. Smith (eds.), Handbook of Experimental Results. New York: Elsevier.

Fischbacher, U. (2007). z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Experimental Economics, 10, 171–178.

Fischhoff, B. (1983). Predicting frames. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory & Cognition, 9, 113–116.

Glaeser, E. L., & Sunstein, C. R. (2009). Extremism and social learning. Journal of Legal Analysis, 1(1), 263–324.

Gneezy, U., Niederle, M., & Rustichini, A. (2003). Performance in competitive environments: gender differences. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(3), 1049–1074.

Goette, L., Huffman, D., & Meier, S. (2006). The impact of group membership on cooperation and norm enforcement: evidence using random assignment to real social groups. American Economic Review, 96(2), 212–216.

Guarnaschelli, S., McKelvey, R. D., & Palfrey, T. R. (2000). An experimental study of jury decision rules. American Political Science Review, 94(2), 407–423.

Hargreaves-Heap, S., & Zizzo, D. J. (2009). The value of groups. American Economic Review, 99(1), 295–323.

Healy, A., & Pate, J. (2011). Can teams help to close the gender competition gap? Economic Journal, 121. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0297.2010.02409.x.

Hey, J. D., Morone, A., & Schmidt, U. (2009). Noise and bias in eliciting preferences. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 39(3), 213–235.

Holt, C. A., & Laury, S. K. (2002). Risk aversion and incentive effects. American Economic Review, 92(5), 1644–1655.

Kerr, N. L., MacCoun, R. J., & Kramer, G. P. (1996). Bias in judgment: comparing individuals and groups. Psychological Review, 103(4), 687–719.

Lorenz, J., Rauhut, H., Schweitzer, F., & Helbing, D. (2011). How social influence can undermine the wisdom of crowd effect. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(22), 9020–9025.

Lusk, J. L., & Coble, K. H. (2005). Risk perceptions, risk preference, and acceptance of risky food. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 87(2), 393–405.

Niederle, M., & Vesterlund, L. (2007). Do women shy away from competition? Do men compete too much? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(3), 1067–1101.

Rook, L. (2006). An economic psychological approach to herd behavior. Journal of Economic Issues, 40(1), 75–95.

Schkade, D., Sunstein, C. R., & Kahneman, D. (2000). Deliberating about dollars: the severity shift. Columbia Law Review, 100(4), 1139–1175.

Schubert, R., Brown, M., Gysler, M., & Brachinger, H. W. (1999). Financial decision-making: are women really more risk-averse? American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings, 89(2), 381–385.

Shupp, R. S., & Williams, A. W. (2008). Risk preference differentials of small groups and individuals. Economic Journal, 118, 258–283.

Sutter, M. (2007). Are teams prone to myopic loss aversion? An experimental study on individual versus team investment behavior. Economics Letters, 97, 128–132.

Sutter, M. (2009). Individual behavior and group membership: comment. American Economic Review, 99(5), 2247–2257.

Tan, J. H. W., & Bolle, F. (2007). Team competition and the public goods game. Economics Letters, 96(1), 133–139.

Wallach, M. A., Kogan, N., & Bem, D. J. (1962). Group influence on individual risk taking. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 65(2), 75–86.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Research support from the Paul Lowham endowment is gratefully acknowledged. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funding source. Jinghui Lim provided excellent research assistance.

Appendices

Appendix A: Measuring risk aversion

To control for individual risk aversion, we obtained a measure of respondent risk aversion in stage 1 of the study. Individuals were asked to choose between two lottery options in ten different cases. The choices presented to subjects are in Table 9.

The ten choices have two options labeled Option A and Option B. These options keep the same dollar and cents values as the choices change. The options are different over the ten choices because the probabilities in the choice change. Option A has progressively higher probabilities for winning $2.00 and progressively lower probabilities for winning $1.60. In Option B there are progressively higher probabilities of winning $3.85 and progressively lower probabilities of winning $0.10. The tenth decision is a choice between taking either $2.00 or $3.85 with certainty. The expected value of Option A in the first decision is $1.64 and the expected value of Option B is $0.475. Both expected values increase, but at a different rate: In choice five the expected value of Option B ($1.975) becomes larger than Option A ($1.80), and a risk-neutral subject should switch from Option A to Option B. Risk-loving subjects will switch sooner, and risk-averse subjects will switch later. Option A is considered a safe choice relative to Option B. One measure of risk aversion is the number of safe choices made before switching to Option B.

After all subjects have chosen either Option A or Option B in each of the ten scenarios, the computer randomly chooses one of the ten scenarios for investment and determines for each subject whether they win or lose their chosen lottery. Before moving to Part II of the experiment subjects are informed of their earnings, and their screen begins to tabulate an earning balance.

Based on their responses to Part I of the experiment and assuming a utility function of the form \( {\text{v}}\left( {\text{x}} \right) = \frac{{{x^{1 - r}}}}{{1 - r}} \), where r is the measure of constant relative risk aversion (CRRA), Table 10 provides the CRRA measure implied by the choice of Option B in the lottery and the fraction of respondents in each risk aversion group. There is a preference for risk if r < 0, and there is risk aversion if r > 0. Using the same intervals as Holt and Laury (2002) for measures of preference, subjects are risk-neutral if they have r such that −0.15 < r < 0.15. Overall, 83% of the respondents are consistent in that they switch from Option A to Option B only once; of those, 17% of the respondents display risk-loving preferences, 28% are risk-neutral, and 55% are risk-averse.Footnote 20 Only 3% of the sample with consistent choices fall into the extremely risk-loving group (r < −0.95) or the extremely risk-averse group (1.37 < r). Most people display moderate degrees of risk aversion. For subsequent analysis we code as the individual’s risk aversion measure the midpoint of the r range or the level of the upper or lower bound on r for people at the extremes. Nobody in the sample failed the rationality test in the final choice in Table 9, and 17% of the sample switched decisions in Table 9 more than once. Subsequent empirical analysis will distinguish the people without r values and label them inconsistent respondents. The mean value of r for those with valid measures of r is 0.21, which is a slight degree of risk aversion. On average consistent subjects made 4.82 safe lottery choices.

Appendix B: Lotteries with rising then falling expected values

To introduce participants to the type of lottery structure used in the main part of the experiment, Part II presents subjects with lottery choice scenarios that have a more complex expected payoff pattern; expected payoffs rise and then fall. Table 11 has nine choices and choosing between options was designed to familiarize the subjects with more complex payoff patterns outside of contextual cues. As shown in Table 11, Option A is winning $2.50 with certainty, but Option B has both the probabilities and investments changing. Once again, after all subjects make their choices, the computer randomly picks one of the nine cases to pay. If subjects pick Option A in that case, $2.50 is paid. If they pick Option B, the computer again decides randomly whether they win the lottery in Option B. The expected value of Option B is shown in parentheses; these values were not given to subjects in the experiment.

Notice the expected values of Option B are always greater than $2.50. A risk-neutral or risk-loving subject would always choose Option B over Option A. A very risk-averse person with an r value of greater than 1.14 will choose Option A from lottery 1 and never switch to Option B. Table 11 is something of a sterile version of the litigation decision that is presented to subjects in Parts III and IV of the experiment, for which the expected values of the lotteries are double the values in Table 11.

Table 12 displays the basic information on when subjects switch from the safe Option A to the lottery in Option B and back. Of all 144 subjects, 127 switch at least once, with an average first lottery switch of 2.18 (std. dev. 1.95) and average last switch (back to Option A) of 7.88 (std. dev. 1.82). The number of times individual subjects switch between Option A and B also are reported. It is not unusual for subjects to make as many as four switches between options. The largest number of switches in the raw data is six. Counts of how individuals are actually switching show that people have difficulty with these lottery choices, which are more challenging than those in the main experiment. Just 56 or 39% of the subjects switch zero or two times; 60 (42%) subjects only switch once, and 28 (19%) switch more than twice.

Complications arise with respect to deciding when to enter and exit the lottery. The survey results from Table 12 present compelling evidence that individuals are uncertain about whether they have made their expected utility-maximizing choices. We believe this uncertainty about their expected utility-maximizing choice allows people to be guided by RTI in a group environment, a theme to which we return when we discuss the experimental results.

The instructions for Table 2 are less demanding of subjects than those for Table 11. In Part II of the experiment, subjects who do not show an extreme risk loving measure are required to enter and then exit the lottery in order to maximize expected utility. Table 2 facilitates the subjects’ task by simply asking them at what point they would like to be in the “litigation lottery” and not when they would like to enter and continue with this lottery as relative payoffs change.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Viscusi, W.K., Phillips, O.R. & Kroll, S. Risky investment decisions: How are individuals influenced by their groups?. J Risk Uncertain 43, 81–106 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-011-9123-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-011-9123-3