Abstract

We examine risk attitudes under regret theory and derive analytical expressions for two components—the resolution and regret premiums—of the risk premium under regret theory. We posit that regret-averse decision makers are risk seeking (resp., risk averse) for low (resp., high) probabilities of gains and that feedback concerning the foregone option reinforces risk attitudes. We test these hypotheses experimentally and estimate empirically both the resolution premium and the regret premium. Our results confirm the predominance of regret aversion but not the risk attitudes predicted by regret theory; they also clarify how feedback affects attitudes toward both risk and regret.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

2Loomes and Sugden (1982) refer to u as a “choiceless utility function”.

If instead the DM does want to hear about (resp., is indifferent to) the foregone prospect’s payoffs, then the resolution premium is negative (resp., zero).

In our set-up, note that the resolution premium is computed independently from the regret premium. So our set-up allows a regret-averse DM to be resolution seeking.

The full list of questions is given in Appendix B (the instructions are available at goo.gl/jKOT3R and goo.gl/3ftKzu).

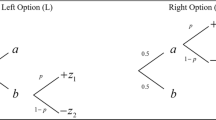

A subject with a concave or convex utility function might prefer the RA prospect despite not being regret averse. For instance, consider a choice between prospects a = (E1, 20; E2, 70; E3, 30) and b = (E1, 45; E2, 25; E3, 50) when all three events are equally likely. Prospect a is a RA prospect because if Q is convex and u is linear then Q(45) > Q(25) + Q(20), in which case a ≽ b. If instead u is convex and Q is linear, we still have a ≽ b. Similar cases occur also when u is concave and Q is linear. To avoid classifying such subjects as regret averse, we included eight questions in which the RA prospect’s EV was lower than that of the RS prospect.

If more than 50% of choices are consistent with H1, we classify the subject and question as “consistent with H1.” In case of indifference, we choose one of the options with equal probability.

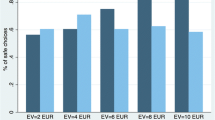

The estimated regret functions of regret-seeking subjects are identical under conditions F and N: Q F (α) = Q N (α) = α0.9. However, feedback increases the number of regret-seeking subjects. In particular, the number (14) of regret-seeking subjects in condition F is significantly larger than the number (3) of regret-seeking subjects in condition N. Feedback therefore decreases the entire subject pool’s regret aversion. The extremely few regret-seeking subjects under condition N precludes any meaningful comparison with their counterparts under condition F.

If the certainty effect influenced our result, then the subjects would have been more consistent with respect to H1 for the second set of questions (since both prospects are risky). However, our evidence points in the opposite direction.

When subjects whose responses in Section II were inconsistent with regret theory are removed and the Q-function is then recomputed, we still find that feedback polarizes regret attitudes.

References

Abdellaoui, M. (2000). Parameter-free elicitation of utility and probability weighting functions. Management Science, 46(11), 1497–1512.

Abdellaoui, M., L’Haridon, O., & Paraschiv, C. (2011). Experienced vs. described uncertainty: Do we need two prospect theory specifications? Management Science, 57(10), 1879–1895.

Anand, P. (1985). Testing regret. Management Science, 31(1), 114–116.

Baillon, A., Bleichrodt, H., & Cillo, A. (2015). A tailor-made test of intransitive choice. Operations Research, 63(1), 198–211.

Barberis, N., Ming, H., & Thaler, R. (2006). Individual preferences, monetary gambles, and stock market participation: A case for narrow framing. The American Economic Review, 96(4), 1069–1090.

Barron, G., & Erev, I. (2003). Small feedback-based decisions and their limited correspondence to description-based decisions. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 16(3), 215–233.

Bell, D. E. (1982). Regret in decision making under uncertainty. Operations Research, 30(5), 961–981.

Bell, D. E. (1983). Risk premiums for decision regret. Management Science, 29(10), 1156–1166.

Bleichrodt, H., Cillo, A., & Diecidue, E. (2010). A quantitative measurement of regret theory. Management Science, 56(1), 161–175.

Bleichrodt, H., & Wakker, P. P. (2015). Regret theory: A bold alternative to the alternatives. The Economic Journal, 125(583), 493–532.

Cohen, M., & Jaffray, J. -Y. (1988). Certainty effect versus probability distortion: An experimental analysis of decision making under risk. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 14(4), 554.

Connolly, T., & Butler, D. (2006). Regret in economic and psychological theories of choice. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 19(2), 139–154.

Connolly, T., & Zeelenberg, M. (2002). Regret in decision making. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 11(6), 212–216.

Diecidue, E., Rudi, N., & Tang, W. (2012). Dynamic purchase decisions under regret: Price and availability. Decision Analysis, 9(1), 22–30.

Engelbrecht-Wiggans, R., & Katok, E. (2008). Regret and feedback information in first-price sealed-bid auctions. Management Science, 54(4), 808–819.

Erev, I., Ert, E., Plonsky, O., Cohen, D., & & Cohen, O. (2017). From anomalies to forecasts: Toward a descriptive model of decisions under risk, under ambiguity, and from experience. Psychological Review, 124(4), 327.

Filiz-Ozbay, E., & Ozbay, E. Y. (2007). Auctions with anticipated regret: Theory and experiment. The American Economic Review, 97(4), 1407–1418.

Fox, C. R., Rogers, B. A., & Tversky, A. (1996). Options traders exhibit subadditive decision weights. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 13(1), 5–17.

Gollier, C., & Salanié, B. (2006). Individual decisions under risk, risk sharing and asset prices with regret. Working paper.

Gonzalez, R., & Wu, G. (1999). On the shape of the probability weighting function. Cognitive Psychology, 38(1), 129–166.

Hertwig, R., Barron, G., Weber, E. U., & & Erev, I. (2004). Decisions from experience and the effect of rare events in risky choice. Psychological Science, 15(8), 534–539.

Josephs, R. A., Larrick, R. P., Steele, C. M., & & Nisbett, R. E. (1992). Protecting the self from the negative consequences of risky decisions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62(1), 26.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–292.

Larrick, R. P. (1993). Motivational factors in decision theories: The role of self-protection. Psychological Bulletin, 113, 440–450.

Larrick, R. P., & Boles, T. L. (1995). Avoiding regret in decisions with feedback: A negotiation example. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 63 (1), 87–97.

Loomes, G. (2010). Modeling choice and valuation in decision experiments. Psychological Review, 117(3), 902.

Loomes, G., & Sugden, R. (1982). Regret theory: An alternative theory of rational choice under uncertainty. The Economic Journal, 92(368), 805–824.

Loomes, G., & Sugden, R. (1987). Some implications of a more general form of regret theory. Journal of Economic Theory, 41(2), 270–287.

Lopes, L. L., & Oden, G. C. (1999). The role of aspiration level in risky choice: A comparison of cumulative prospect theory and SP/A theory. Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 43(2), 286–313.

Michenaud, S., & Solnik, B. (2008). Applying regret theory to investment choices: Currency hedging decisions. Journal of International Money and Finance, 27(5), 677–694.

Muermann, A., & Volkman, J. (2006). Regret, pride, and the disposition effect. Working paper.

Nasiry, J., & Popescu, I. (2012). Advance selling when consumers regret. Management Science, 58(6), 1160–1177.

Perakis, G., & Roels, G. (2008). Regret in the newsvendor model with partial information. Operations Research, 56(1), 188–203.

Qin, J. (2015). A model of regret, investor behavior, and market turbulence. Journal of Economic Theory, 160, 150–174.

Ritov, I. (1996). Probability of regret: Anticipation of uncertainty resolution in choice. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 66(2), 228–236.

Ritov, I., & Baron, J. (1995). Outcome knowledge, regret, and omission bias. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 64(2), 119–127.

Starmer, C. (2000). Developments in non-expected utility theory: The hunt for a descriptive theory of choice under risk. Journal of Economic Literature, 38(2), 332–382.

Starmer, C., & Sugden, R. (1993). Testing for juxtaposition and event-splitting effects. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 6(3), 235–254.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1992). Advances in prospect theory: Cumulative representation of uncertainty. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 5(4), 297–323.

Tversky, A., & Wakker, P. (1995). Risk attitudes and decision weights. Econometrica, 63(6), 1255–1280.

van de Kuilen, G. (2009). Subjective probability weighting and the discovered preference hypothesis. Theory and Decision, 67(1), 1–22.

Viefers, P., & Strack, P. (2014). Too proud to stop: Regret in dynamic decisions. Working paper.

von Neumann, J., & Morgenstern, O. (1947). Theory of games and economic behavior. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Wakker, P. (2010). Prospect theory for risk and ambiguity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Zeelenberg, M. (1999). Anticipated regret, expected feedback and behavioral decision making. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 12(2), 93–106.

Zeelenberg, M., & Beattie, J. (1997). Consequences of regret aversion 2: Additional evidence for effects of feedback on decision making. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 72(1), 63–78.

Zeelenberg, M., Beattie, J., Van der Pligt, J., & & de Vries, N. K. (1996). Consequences of regret aversion: Effect of expected feedback on risky decision making. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 65, 148–158.

Acknowledgements

We thank Aurélien Baillon, Han Bleichrodt, Luc Wathieu, Klaus Wertenbroch, Horst Zank, the editor, and an anonymous referee for their helpful comments. We also gratefully acknowledge support from the People Program (Marie Curie Actions) of the European Union’s Seventh Framework Program FP7/2007–2013/ under REA grant agreement 290255.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendices

Appendix A

1.1 Example of experimental stimuli for Sections I and II

Appendix B

1.1 Questions used in Sections I and II of the lab experiment

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Somasundaram, J., Diecidue, E. Regret theory and risk attitudes. J Risk Uncertain 55, 147–175 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-017-9268-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-017-9268-9