Abstract

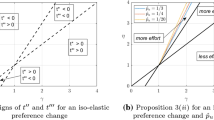

This paper provides experimental evidence of the role of higher order risk attitudes—especially prudence—in prevention behavior. Prudence, under an expected utility framework, increases (decreases) self-protection effort compared to the risk neutral level when the risk of losing part of an income exists in a future (the same) period. Motivated by these predictions that give the exact test on prudence, an experiment was designed where subjects go through higher order risk attitude elicitation and make a self-protection decision. In contrast to the expected utility theory, the observed efforts are less than the risk neutral level, regardless of the timing of loss. This violation of expected utility predictions can be explained by probability weighting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See also Gollier et al. (2013) for a survey of higher order risk theory.

Gollier (2004) also explains this role of prudence in Chapter 16.

1 ECU=20 KRW in the Seoul National University sessions.

Through the comparative statics presented in Sect. 2 (Propositions 1 and 2), neither result restricts the functional form of the probability of loss. Our functional form \(p = 1/(\,1 + ke)\)\(,\,k > 0\) has two features. First, the odds against loss proportionally increase in effort (Note \(\,ke = \,(1 - p)/p\)). Second, a simple solution can be derived for the risk-neutral optimal effort \(e_{n} = 1/k\) and the size of loss \(\,d = 4/k\).

We provide the screenshots for feedback depending on treatments in “Online Appendix A”.

In “Online Appendix”, we explain the details of the process in Part 3 and its instructions.

We also tested whether Osaka and Seoul subjects differ in risk attitudes, as reported in “Online Appendix B”. There is no significant difference in risk attitudes between Osaka and Seoul subjects.

Instructions and an explanation of the time discount variable are in “Online Appendix A”.

Regarding the time discount variable, subjects who discount more have a tendency to exert more effort in C treatment, although the mechanism is unclear because C treatment is not an intertemporal choice problem.

“Online Appendix C” reports the distribution for our elicited time preference and how the risk neutral level was recomputed considering time preference. We also confirm that Menegatti’s (2009) theoretical result holds after considering time discounting.

Eeckhoudt et al. (2017) also assume linear utility.

References

Bleichrodt, H., & van Bruggen, P. (2018). Higher order risk preferences for gains and losses. Working Paper.

Cardella, E., & Kitchens, C. (2017). The impact of award uncertainty on settlement negotiations. Experimental Economics, 20(2), 333–367.

Courbage, C., Rey, B., & Treich, N. (2013). Prevention and precaution. Handbook of insurance (pp. 185–204). New York, NY: Springer.

Deck, C., & Schlesinger, H. (2010). Exploring higher order risk effects. The Review of Economic Studies, 77(4), 1403–1420.

Deck, C., & Schlesinger, H. (2014). Consistency of higher order risk preferences. Econometrica, 82(5), 1913–1943.

Ebert, S., & Wiesen, D. (2011). Testing for prudence and skewness seeking. Management Science, 57(7), 1334–1349.

Ebert, S., & Wiesen, D. (2014). Joint measurement of risk aversion, prudence, and temperance. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 48(3), 231–252.

Eckel, C. C., & Grossman, P. J. (2008). Men, women and risk aversion: Experimental evidence. Handbook of Experimental Economics Results, 1, 1061–1073.

Eeckhoudt, L., & Gollier, C. (2005). The impact of prudence on optimal prevention. Economic Theory, 26(4), 989–994.

Eeckhoudt, L. R., Laeven, R. J., & Schlesinger, H. (2017). Risk apportionment: The dual story. arXiv preprint arXiv:1712.02182.

Eeckhoudt, L., & Schlesinger, H. (2006). Putting risk in its proper place. The American Economic Review, 96(1), 280–289.

Fischbacher, U. (2007). z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Experimental Economics, 10(2), 171–178.

Gollier, C. (2004). The economics of risk and time. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Gollier, C., Hammitt, J. K., & Treich, N. (2013). Risk and choice: A research saga. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 47(2), 129–145.

Gollier, C., Jullien, B., & Treich, N. (2000). Scientific progress and irreversibility: an economic interpretation of the ‘Precautionary Principle’. Journal of Public Economics, 75(2), 229–253.

Greiner, B. (2015). Subject pool recruitment procedures: organizing experiments with ORSEE. Journal of the Economic Science Association, 1(1), 114–125.

Haering, A., Heinrich, T., & Mayrhofer, T. (2017). Exploring the consistency of higher-order risk preferences (No. 688). Ruhr Economic Papers.

Heinrich, T., & Mayrhofer, T. (2018). Higher-order risk preferences in social settings. Experimental Economics, 21(2), 434–445.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–292.

Kimball, M. S. (1990). Precautionary saving in the small and in the large. Econometrica, 58(1), 53–73.

Kocher, M. G., Pahlke, J., & Trautmann, S. T. (2015). An experimental study of precautionary bidding. European Economic Review, 78, 27–38.

Krieger, M., & Mayrhofer, T. (2017). Prudence and prevention: An economic laboratory experiment. Applied Economics Letters, 24(1), 19–24.

Leland, H. E. (1968). Saving and uncertainty: The precautionary demand for saving. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 82(3), 465–473.

Menegatti, M. (2009). Optimal prevention and prudence in a two-period model. Mathematical Social Sciences, 58(3), 393–397.

Noussair, C. N., Trautmann, S. T., & Van de Kuilen, G. (2014). Higher order risk attitudes, demographics, and financial decisions. Review of Economic Studies, 81(1), 325–355.

Peter, R. (2017). Optimal self-protection in two periods: On the role of endogenous saving. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 137, 19–36.

Prelec, D. (1998). The probability weighting function. Econometrica, 66(3), 497–527.

Schmidt, U., Starmer, C., & Sugden, R. (2008). Third-generation prospect theory. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 36(3), 203.

Stott, H. P. (2006). Cumulative prospect theory’s functional menagerie. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 32(2), 101–130.

Trautmann, S. T., & van de Kuilen, G. (2018). Higher order risk attitudes: A review of experimental evidence. European Economic Review, 103, 108–124.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1992). Advances in prospect theory: Cumulative representation of uncertainty. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 5(4), 297–323.

Wakker, P. P. (2010). Prospect theory: For risk and ambiguity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

White, L. (2008). Prudence in bargaining: The effect of uncertainty on bargaining outcomes. Games and Economic Behavior, 62(1), 211–231.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank Charles Noussair for his continuous encouragement and helpful suggestions, which improved our paper significantly. We thank Soo Hong Chew, Syngjoo Choi, Nobuyuki Hanaki, Stefan Trautmann, Songfa Zhong, the participants of 2017 ESA North American Meeting, the University of Arizona experimental reading group, and the SURE workshop at Seoul National University. Sebastian Ebert kindly shared with us their z-Tree programs. Masuda completed most of this study during his visit to the Economic Science Laboratory at the University of Arizona. We gratefully acknowledge the financial support received from JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 17K13701, 15H05728, the Keihanshin Consortium for Fostering the Next Generation of Global Leaders in Research (K-CONNEX), the John-Mung Overseas Program, and the Murata Science Foundation. Lee acknowledges funding from the BK21Plus Program of the Ministry of Education and National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-21B20130000013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix A. Proofs

Appendix A. Proofs

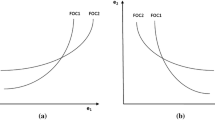

Proof of Proposition 3

(1) Future loss. Take any \(\upgamma \in (0,1]\). An \(\upgamma\)-Prelec player chooses effort e to maximize

where \(q = q(e) = 1 - p(e) = ke/(1 + ke)\). First, we check the first order condition.

By substituting \(dw^{\upgamma } /dq = (\upgamma ( - \ln q)^{\upgamma - 1} /q) \cdot w^{\upgamma } (q)\), \(p(e_{n} ) = 1/2,\) and \(- p^{\prime}(e_{n} ) = 1/d,\)

Since

by \(0 < \upgamma \le 1,0 < (\ln 2)^{\upgamma } \le 1\,{\text{and - 1}} < \ln (\ln 2) < 0\), we have

Second, we check the second order condition. Since

and ke = q/(1-q), it suffices to show \(h(q,\upgamma ) = 1 + \upgamma \left( { - 1 + \left( { - \ln q} \right)^{\upgamma } } \right) + \frac{1 + q}{1 - q}\ln q \le 0\) for all \(q \in (0,1]\) and \(\upgamma \in (0,1]\).

Let e be Napier’s constant.

Case 1

\(q \in (0,{\mathbf{e}}^{ - 1} ]\)

Since

\(h(q,\upgamma ) \le h(q,1) = 2q\ln q/(1 - q)\) for all \(q \in (0,{\mathbf{e}}^{ - 1} ]\) and \(\upgamma \in (0,1]\). Hence,\(h(q,\upgamma ) \le h(q,1) < \mathop {\lim }\limits_{q \to 0} h(q,1) = \mathop {\lim }\limits_{q \to 0} \frac{2q\ln q}{1 - q} = 2 \cdot 1 \cdot \mathop {\lim }\limits_{q \to 0} q\ln q = 2 \cdot \left( { - \mathop {\lim }\limits_{r \to \infty } \frac{\ln r}{r}} \right) = 0\quad {\text{for}}\,{\text{all}}\,\)\(q \in (0,q*]\) and \(\upgamma \in (0,1]\).

Case 2

\(q \in ({\mathbf{e}}^{ - 1} ,1]\)

Since

\(h(q,\upgamma ) \le h(q,0) = 1 + \frac{1 + q}{1 - q}\ln q\) for all \(q \in ({\mathbf{e}}^{ - 1} ,1]\) and \(\upgamma \in (0,1]\). Hence,

Hence, the objective function is concave.

(2) Current loss. The same argument holds by linearity of valuation function of money. ||

Proof of observation

Take any a, b, z with a > b. \(L = (a,.50;b + z,.25;b - z),R = (a + z,.25;a - z,.25;b).\)

Suppose a > b + z.

Then

The last inequality holds by \(w(.75) - w(.25)\, \le 0.5\) for any Prelec function.

Suppose next a < b + z.

Then

The last inequality holds by \(w(.75) - w(.25)\, \le 0.5\) for any Prelec function.||

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Masuda, T., Lee, E. Higher order risk attitudes and prevention under different timings of loss. Exp Econ 22, 197–215 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-018-9588-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-018-9588-x