Abstract

A large literature shows that citizens care about the procedural fairness of rules and institutions. This body of work suggests that citizen evaluations of institutional changes should be constrained by fairness considerations, even if they would personally benefit from the reforms. We test this expectation using two panel studies to examine whether citizens become more accepting of proposals rated as unfair (in wave one) after we experimentally manipulate (in wave two) whether the proposals aid their party’s electoral prospects. Using this approach, we are able to establish what citizens see to be fair or unfair separate from their evaluation of a given rule change. We find that supporters of both parties are consistently more favorable toward reforms their fellow partisans and, crucially, they themselves, claim reduce electoral fairness when framed as advancing their partisan interests. The results provide important insights into how citizens evaluate electoral processes, procedural fairness, and, hence, the acceptable limits of institutional change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Although there is typically a component of partisan self-interest in how the average citizen sees electoral institutions, a large literature posits that ideas of “fairness” and in particular “procedural fairness” are important attributes of rules, institutions, and processes for the general public (Tyler, 2006).Footnote 1 Procedural fairness, or the (perceived) impartiality of how results are generated, is strongly tied to broader considerations of institutional legitimacy and the acceptance of undesired outcomes (e.g., Gangl, 2003; Hibbing & Alford, 2004; Zink et al., 2009). This body of work implies both that citizens are committed to notions of fairness and also apply those commitments when assessing the political system, which should make individuals hesitant to embrace system reforms that violate their conception of fairness even if the party they support may benefit from such reforms (Bowler & Donovan, 2013).

In contrast, an alternative view signals that fairness principles exert a more limited effect on whether one approves of modifying electoral procedures. Some prior research suggests that, in practice, citizens grant politicians latitude to amend laws governing the selection of elected officials, the ease of ballot access for eligible voters, and the role of citizens in the legislative process for partisan gain (e.g., Anderson et al., 2005; Biggers, 2019; Tolbert et al., 2009).

Adjudicating between these two views of citizen response to electoral policy change is difficult, however, as work to date fails to assess perceptions of institutional fairness. Absent a measure of perceived fairness that is separate from attitudes toward the proposed change, we cannot know for sure how citizen commitments to procedural fairness and their partisan interests shape electoral reform support.

In this paper, we address that shortcoming by conducting and replicating a two-wave panel study. In the first wave, subjects evaluated the extent to which the adoption of ten different proposed electoral policies would make contests more or less fair. This panel design allows us to measure, rather than assume, which reforms cross acceptable boundaries of fairness for respondents. In wave two (a week later), we asked those same subjects their level of support for the policies identified by co-partisans as the most unfair after we experimentally manipulated whether the proposal would aid or hinder their party’s electoral prospects. We therefore directly test whether citizens become more favorable toward changes believed to be unfair (at least in the abstract) when adoption improves their party’s chances at the polls. In measuring fairness assessment and policy support in different waves, we minimize concerns about subjects inaccurately reporting their true policy support level so as to ensure that their stated evaluation is consistent with their prior judgment of fairness.

Overall, we find that citizen responses to institutional changes perceived as unfair are generally not resistant to partisan considerations. For reforms deemed most unfair by their co-partisans, members of both parties in the two studies are consistently more favorable toward their implementation when doing so advances, rather than hinders, their partisan self-interest. This attitudinal shift occurs on proposals to require a civics test before one can vote, discard mismarked ballots when the voter’s intention is clear, remove registrants from the voter rolls for inactivity, and, for Republicans, impose a poll tax. More importantly, these results generally hold for those respondents who themselves rated the adoption of the named proposal as making elections less fair. That is, despite their own assessment that a given proposal reduces the fairness of elections, citizens become more amenable to its enactment if informed that doing so enhances their team’s electoral prospects.

These findings have a number of implications. For one, they pose questions for theories of legitimacy that emphasize the procedural fairness of institutions as opposed to the outcomes they produce. In these highly partisan times, the fact that we show that citizens become more supportive of institutions when told they benefit their party may strike some as reasonable but somewhat unsurprising. The novelty of our results, however, is that this partisan effect occurs in individuals shifting their attitudes on the acceptability of a proposal they previously assessed as unfair. Yet the procedural fairness literature sees fairness as a matter of underlying principle for citizens. Moreover, while it may be the case that partisans differ in their definitions of fair, we show the effect holds even for that definition. That is, our two wave approach allows us to show that even when citizens perceive the changes as unfair in terms of their own sense of “fairness,” they are more willing to support unfair changes if they provide a partisan advantage. It is the case that we find that people do not appear to entirely abandon fairness for partisan gains. But while the shift away from fairness that we see is relatively modest, it is nevertheless real. Our results thus suggest that at least some ideas of fairness are less rigid than believed, and that we may need to revisit the importance of procedural justice as a criterion relevant to citizens weighed against other considerations (see also Esaiasson et al., 2019). We expand upon these and other implications, as well as avenues for future work, in the conclusion.

The Role of Fairness and Partisan Self-Interest in Evaluating Reforms

Efforts to modify electoral institutions are consistently characterized as motivated by self-interest and the anticipation of political gain (e.g., Boix, 1999), with political actors’ support for altering the current system generally hinging on whether a proposed change is perceived to provide a clear electoral advantage (e.g., Bowler et al., 2006). While models of rational self-interest guide how we understand elites’ attitudes and behaviors over institutional change, it is far from clear how well those models apply to citizens. A major rival expectation comes from the literature largely grounded in the social-psychological work of Tyler and colleagues (e.g., Tyler, 1988; Tyler et al., 1989). This second body of work stresses the importance that citizens place on procedural fairness in evaluating institutions. Individuals are seen to care not only if a process or institution yields their desired outcome, but also (and perhaps even more) if the rules under which the process or institution generated that outcome were fair and impartial. Importantly, these ideas of fairness exist independent of self-interest (or are only modestly affected by it) and either moderate self-interest or are, or at least should be, applied independently of that interest. From within the procedural justice literature, the criticism “that’s not fair” should generally not vary for an individual regardless of whether a reform does or does not advance their electoral or policy goals.

A substantial body of work in U.S. and comparative contexts demonstrates empirical support for the procedural justice framework. Higher levels of perceived procedural fairness increase support for or induce positive evaluations of a host of governmental institutions, political actors, and the decisions made by those institutions and actors (Gangl, 2003; Hibbing & Alford, 2004; Hibbing & Theiss-Morse, 2002; Zink et al., 2009). This literature also signals that fairness evaluations condition responses to political actions. Policy outcomes, even those that are undesired, are generally perceived as more legitimate – and thus accepted by citizens – if the process through which they occurred is considered fair. Furthermore, prior work explicitly links fairness judgments to limiting the push for institutional reform based on partisan self-interest (Bowler & Donovan, 2013). The expectation that citizens have these concerns may help explain why politicians often couch proposed changes to electoral institutions not in terms of self-interest but in terms of normative principles consistent with fairness considerations (e.g., concerns about access or legality) (Bowler & Donovan, 2013). How individuals define fairness or come to evaluate processes and institutions as fair is the subject of debate (e.g., Doherty & Wolak, 2012), but regardless of that mechanism fairness considerations should exert a significant impact on one’s willingness to support or oppose reforming the existing system.

Further contributing to that expectation is the often cited relationship of democratic rules and institutions to broad ranging values and principles. This is particularly true for voting, which citizens are repeatedly told is important in itself and an act of societal value. It should therefore not be surprising that individuals often respond to rules in terms of those principles. For example, a large portion of the American public sees voting as a civic duty (Blais, 2000), and experimental evidence shows the impact of social pressure on the motivation to participate (e.g., Gerber et al., 2008). When it comes to proposed changes to voting rules, especially those that affect access to the polls, we might reasonably expect a dedication to fairness to temper the inclination toward pursuing a partisan advantage. This is because electoral policies directly link to two procedural characteristics that consistently shape procedural fairness evaluations: “voice,” which in the context of elections refers to the ability to take part, and “equal treatment,” which relates to people having equal influence (Wilking, 2011). Some evidence supports this conjecture, as Wilson and Brewer (2013) show that Democrats become less supportive of voter ID laws when told that the requirement might keep some eligible citizens from turning out.Footnote 2

In addition to those findings that demonstrate the relevance of procedural concerns, there is also substantial prior work suggesting that citizen assessments of electoral policies are nevertheless strongly grounded in partisan self-interest and the outcomes they are likely to produce. Those aligned with the party out of power, for example, express greater support for institutional reforms (e.g., proportional representation, direct election of the president, changing redistricting procedures) that would presumably enhance their voice in the political process and/or their prospects of obtaining power (Anderson et al., 2005; Banducci & Karp, 1999; Fougere et al., 2010; Karp & Tolbert, 2010). That support often appears to reflect a calculated evaluation, as co-partisans may take different stances on the reform depending on how it might improve electoral prospects in their particular context (e.g., Smith et al., 2010; Tolbert et al., 2009). Partisans also tend to hold preferences that strongly align with those of their team’s elites on policies related to political engagement, such as the ease of registration and participation and the types of identification necessary to vote (Alvarez et al., 2011; Kane, 2017). Furthermore, studies that experimentally manipulate whether Republicans or Democrats benefit from specific reforms generally find that members of both parties shift their support for these policies depending on whether it is electorally beneficial (Biggers, 2019; Kane, 2017; McCarthy, 2019), though these changes are often modest in magnitude and do not correspond to radical departures from general support levels.

In weighing these competing explanations for how citizens see changes to voting rules, the real difficulty is not in advancing a hypothesis relating to one explanation versus the other but in providing evidence that speaks to that balance. It is an exaggeration to say that there are two directly opposed and mutually exclusive explanations of popular views on institutions grounded in the role of self-interest and procedural concerns, respectively. The debate is one more of relative importance of the two explanations rather than which one is correct and which one is wrong. Nevertheless, there is still room to speak to how citizens weigh these two considerations. To date, for example, studies that provide evidence of self-interest fail to measure, and instead simply makes assumptions about, perceptions of and the role for fairness. This failure makes it difficult to disentangle principle from self-interest, as what may seem to be an expression of partisan self-interest could, in fact, be an expression of principle.

Broadly speaking, rules that extend access are instituted by Democrats (Biggers & Hanmer, 2015) while rules that emphasize ensuring those who vote are entitled to do so are passed by Republicans (Bentele & O’Brien, 2013; Biggers & Hanmer, 2017). Such efforts are generally framed as a debate over protecting electoral integrity (Republicans) and ensuring eligible voters are not disenfranchised (Democrats), but these policies often have differential impacts on the ethnic, racial, and/or socioeconomic composition of electorates that potentially affect their partisan composition (Hajnal et al., 2017; Hanmer, 2009). As such, support for these rules or changes is often interpreted as reflecting partisan self-interest, but it can also potentially reflect competing values at work. For someone who believes that voter fraud occurs at a rate that threatens electoral integrity, rule changes they perceive to combat that fraud (e.g., requirements to show photo identification to vote) are not about keeping minority voters from the polls but about making elections fair. Reforms thus portrayed by one side as gaming the electoral system (i.e., making it less fair) may instead be sincerely viewed by the other side as enhancing the fairness of electoral contests. Without first determining what citizens perceive as fair or not fair, we cannot empirically assess whether electoral interests sway support for rule changes seen as procedurally unfair.

Research Design

To investigate the willingness of citizens to game the electoral system for partisan advantage, we conducted, and then replicated, a two-wave panel study. In the first wave, subjects evaluated the extent to which the adoption of different electoral policies would make elections more or less fair. Using that information, we identified the proposals deemed most unfair by Republicans and Democrats, respectively. In the second wave, we measured support for those reforms subjects’ fellow partisans believe are the most unfair after experimentally manipulating which party benefits from them. This design allows us to determine whether citizens are less opposed to proposals they and/or their co-partisans previously evaluated as unfair when those proposals are framed as improving their party’s electoral prospects. Additionally, by asking about policy fairness and support in separate waves, we avoid the concern that subjects might inaccurately report their policy support to ensure that evaluation is consistent with their previously stated fairness assessment.

Study 1 uses subjects recruited in March 2017 from Amazon.com’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) web-based crowdsourcing service. As with prior work (Berinksy et al., 2012), this sample is more Democratic and educated, younger, and less gender balanced than the general population. Study 2 uses subjects provided in March–April 2018 by Survey Sampling International (SSI).Footnote 3 This sample is noticeably more diverse, as it exhibits gender parity, greater racial/ethnic diversity, and a significantly larger proportion of less educated individuals (see Table S1). Although neither sample is nationally representative, recent research demonstrates that nationally representative and non-representative convenience samples respond similarly to experimental treatments (e.g., Coppock et al., 2018).

Wave 1

After completing qualification questions (U.S. citizen 18 or older),Footnote 4 subjects assessed in random order how more or less fair elections would be if ten proposed reforms were adopted by all states (much more, somewhat more, slightly more, neither more nor less, slightly less, somewhat less, much less). Each policy description was neutral in nature and provided an argument for and against it. Subjects then answered demographic, socioeconomic, and political questions. We obtained completed surveys from 561 Republicans and 1096 Democrats in Study 1 to 929 Republicans and 937 Democrats in Study 2.Footnote 5

In selecting the evaluated reforms, we chose ones that we anticipated large numbers of at least one party’s members would view as unfair. Our goal was not to establish how fair rank-and-file Republicans and Democrats view specific election policies (which we cannot do with our non-representative samples). Nor was it to determine why specific reforms were viewed as unfair or how subjects weighed perceptions of procedural characteristics like voice and equal treatment in assessing fairness (which we do not measure). Instead, we hoped to identify a set of seemingly objectionable proposals that may become more acceptable to partisans if their enactment would advance their team’s electoral prospects.

For example, many of the policies are cited as challenging electoral fairness by increasing the probability of voter fraud or the disenfranchisement of eligible citizens (which link to considerations about the ability to take part and have equal influence). Based on how the parties prioritize those considerations, these proposals should violate fairness notions for Republicans and Democrats, respectively. These include (1) requiring photo ID to vote, (2) allowing registrants to vote early before Election Day, (3) permitting eligible citizens to both register and vote on Election Day (Election Day registration, or EDR), (4) canceling one’s voter registration due to inactivity (purging registrants), (5) automatically registering individuals when they interact with a government agency, and (6) requiring proof of citizenship to register to vote. Other proposals do not clearly involve a trade-off between ballot access and electoral integrity but still invoke influential procedural attributes like voice and equal treatment. Two additional proposals expand local election official discretion to (7) keep polls open past their scheduled closing time and (8) discard (i.e., not count) incorrectly marked ballots even when the voter’s intention is clear. The final reforms involve before one could vote a (9) civics test and (10) payment of a poll tax. These issues vary across multiple dimensions that might influence perceived fairness: impact on the ease of registration or voting, familiarity to the general public, and preexisting expectations as to whom (and thus which parties) are affected by their presence.

Figure 1 presents respondents’ electoral reform evaluations.Footnote 6 Panel A reports the proportions of Republicans and Democrats in Study 1 who state the proposals make elections less fair (slightly, somewhat, or much). Panel B does the same for Study 2. As is evident, there are noticeable differences by partisanship in perceived fairness that generally correspond to how the reform affects engagement costs. For example, comparing within studies, Democrats are 18 to 38 percentage points more likely than Republicans to view requiring proof of citizenship to register and photo ID to vote as unfair. In contrast, Republicans see the reforms that facilitate voting as less fair, including EDR (by 13 to 30 points), automatic registration (by 17 to 25 points), and election official discretion to keep polls open after closing time (by 9 to 20 points).

On other matters, however, greater agreement prevails. Although Republicans are less inclined than Democrats to believe the proposals make elections less fair, in both studies members of the two parties rank a civics test, discarding mismarked ballots when the voter’s intention is clear, and a poll tax as among the four most unfair proposals. Those perceptions are shared by 35–79% of Republicans and 51–93% of Democrats. Regardless of how Democrats and Republicans subjectively define fairness or weigh considerations like voice and equal treatment, they tend to agree on which policies are the least fair (though perhaps not why). Otherwise, there are considerable differences in the acceptability of the proposals.

Wave 2

Having identified the policies that partisans classify as the most unfair (in the abstract), we then tested whether citizens become more favorable toward those changes when adoption is framed as improving their party’s electoral chances. One week after completing the first wave, we invited subjects to take a second survey. Respondents asserted their support using a four category scale (strongly favor, somewhat favor, somewhat oppose, strongly oppose) for four election reforms rated by co-partisans as among the most unfair (as measured in wave one and reported in Fig. 1). After sending a reminder a few days after the initial invitation to those who had yet to participate, we achieved re-contact rates of 78.9% in Study 1 and 69.5% in Study 2 (with rates roughly identical across parties within a given study).

Three proposals used in wave two were constant across parties in both studies: a civics test, a poll tax, and making it easier to discard mismarked ballots even though the voter’s intention is clear. In Study 1 and for Study 2 Democrats, the fourth reform was purging registrants from the rolls for inactivity, while for Study 2 Republicans it was permitting Election Day registration.Footnote 7 Within party (measured in wave one), we randomly assigned subjects to one of three reform question versions that gauged policy support given that it would disproportionately affect some group. Those versions appear in Table 1. The control conditions (first row) use the exact same language from the wave one survey to describe those affected generically without referencing their partisanship (e.g., “voters” or “citizens”).Footnote 8 In the other two conditions, we describe those affected as citizens or voters “who tend to support the Republican (Democratic) Party” (see row two).Footnote 9

One concern about this approach is that subjects may receive differing frames for the four questions, as we randomly assign treatment for each reform. One policy, for example, might be described as benefiting Republicans, while another policy lacks a cue about partisan effects (with the first frame conceivably impacting how subjects respond to subsequent questions). To minimize this possibility, we included five non-election policy assessments between each election reform question to serve as a distractor task by forcing subjects to think about a wide range of other issues. We also randomized the reform question order.

We estimate OLS regression models for each policy in each study, where the dependent variable is the four category scale ranging from strongly favor (1) to strongly oppose (4). These models include treatment assignment indicators for whether the reform helps one’s team or hurts one’s team (improves or hinders their party’s electoral prospects, respectively). The “helps team” variable corresponds to Republicans told that EDR makes it more likely that Republicans will vote and, for all other reforms, Democrats (Republicans) told the policy makes it less likely that Republicans (Democrats) will vote or have their votes counted. In contrast, the “hurts team” variable captures Republicans told that EDR makes it more likely that Democrats will vote and those told that any other reform makes it less likely that co-partisans will vote or have their votes counted. We interact these variables with Republican Party affiliation (449 in Study 1 and 641 in Study 2) to account for potential partisan heterogeneous effects (the 858 Study 1 and 656 Study 2 Democrats are the out-group). Although we lack strong expectations for differential effects, we test for them because prior work that primes partisan self-interest sometimes finds larger shifts in Republican reform attitudes (e.g., Biggers, 2019) and to ensure that pooling partisans does not mask such effects.Footnote 10

These models estimate the effects of the treatments compared to the control condition, but our primary comparison of interest is between the two treatments which we conduct through linear combination of coefficients tests. This allows us to assess whether partisans become more supportive of the policy when told it benefits their team rather than their opponents. We focus on this test because we suspect that although the control conditions do not state whose participation the reform will affect, many subjects nonetheless perceive the described “voters” or “citizens” as Democrats or members of a group (e.g., racial/ethnic group) associated with the party (given that they tend to actually be disproportionately impacted by the reforms).Footnote 11 A separate MTurk study discussed in the SI supports this suspicion. Respondents read the five reform control condition prompts from the two studies and reported how more or less likely they thought Republicans and Democrats would be to vote or have their votes counted if each reform was adopted. For those Democrats who anticipate a partisan effect, 55%-70% identify the reforms as more likely hurting their team. These gaps are more modest for Republicans, as 51%-59% expect adoption to more negatively impact Democrats (though 57% think EDR will benefit co-partisans more).

Such perceptions have important consequences for estimating the effect of partisan self-interest. They mean, for example, that a sizable number of Democrats (Republicans) in each reform control condition are essentially assigned the hurts (helps) team treatment. This in turn reduces the estimated impact of those treatments compared to the control. Alternatively, some Democrats (Republicans) assigned the helps (hurts) team message receive information counter to their pre-existing beliefs that may shift attitudes less than if they had no prior expectations of the reform’s consequences. By comparing the two treatments, we avoid concerns about the inability to identify which subjects infer partisan preferences for those referenced in the control group (though we discuss and interpret the treatment to control comparisons below).

Results

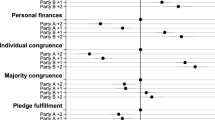

We begin with Study 1. In Panel A of Fig. 2, we plot the effect of the “hurts team” treatment on support for each reform (compared to the “helps team” treatment) for Democrats and Republicans. Positive values signify greater support when the policy benefits their party. These estimates pertain to all subjects (regardless of whether they personally view the reform as unfair) and are presented with 90% confidence intervals (given the clear directionality of the hypothesized relationships, we report one-sided p-values for these tests).Footnote 12 As is evident, the treatments consistently cause opinion shifts that are in line with subjects’ partisan self-interest. Democrats (denoted by the grey circles) are about one-fifth of a point (on a four point scale) more supportive of requiring one pass a civics test to vote, purging registrants for inactivity, and making it easier to discard mismarked ballots despite the voter’s intention being clear when doing so is framed as enhancing rather than hurting their team’s electoral prospects (all p < 0.01). The one exception to this pattern is imposing a poll tax, which 94% of wave two respondents rated as unfair. For this proposal, there is essentially no difference in support regardless of who is affected. Thus for all but the perceived most extreme policy, Democrats are somewhat more willing to enact a reform that they as a whole assess as unfair if it provides a partisan gain.

Effect of Partisan Treatments on Opposition to Election Reforms. Note: Symbols are linear combination of coefficients tests for OLS regression model estimates of the effect of the “hurts team” compared to “helps team” treatments on election reform support (1 = strongly favor, 4 = strongly oppose). Range spikes are 90% confidence intervals

The effects for Republicans are even larger (denoted by the black squares). GOP subjects are about one-third to one-half of a point more favorable toward a civics test, purging registrants for inactivity, and allowing mismarked ballots to be discarded when doing so negatively affects Democrats versus hurting Republicans (all p < 0.01). These effect sizes are 1.5 to 2 times those observed for Democrats. Furthermore, for all three reforms the mean level of support shifts from above the midpoint on the four point scale (2.5) when the policy hurts Republicans to below it when the policy helps Republicans (essentially moving from somewhat oppose (3) to somewhat support (2)). Specifically, support shifts from 2.6 to 2.3 for a civics test, 2.6 to 2.1 for voter purges, and 2.8 to 2.4 for allowing the discarding of mismarked ballots. We observe no similar changes among Democrats, for whom none of the treatment effects reduce average levels of support below 3.0. Finally, in contrast to Democrats, Republicans express greater support (by roughly one-fifth of a point) for adopting a poll tax if it benefits their electoral prospects (p = 0.01).Footnote 13

Panel B of Fig. 2 presents the same set of analyses for Study 2. The results largely mirror those of Study 1, though the evidence that individuals respond to partisan self-interest primes is slightly weaker. As in Study 1, Democrats become more in favor of purging registrants for inactivity and giving officials greater discretion to discard mismarked ballots when doing so improves rather than hurts their party’s chances (p = 0.03 and p = 0.01, respectively). The size of these changes in support (roughly one-fifth of a point) is about the same as observed among Study 1 Democrats. Study 2 Democrats also express greater support for a civics test when told it will keep some Republicans from voting, but this effect (unlike in Study 1) is not significant (p = 0.18). Democrats’ attitudes toward a poll tax again do not shift regardless of which party it benefits.

As in Study 1, Republicans are significantly more supportive of all reforms when they impede the opposition (all p < 0.01). These effects are roughly the same size as those in Study 1 for a civics test and poll tax (both 0.26 of a point), though for giving officials more discretion to toss mismarked ballots the effect is smaller (0.25 vs. 0.38).Footnote 14 Study 2 Republicans also become more favorable toward EDR (which we did not ask about in Study 1) by 0.43 points when its adoption helps co-partisans vote. For both granting greater discretion to discard ballots and EDR, the treatment effects cause mean attitudes to shift across the scale midpoint from oppose to support (2.7 to 2.4 and 2.8 to 2.3, respectively). Across both studies then, Democrats express less opposition to three of the four proposals that co-partisans rate as the most unfair when adoption benefits their party electorally, while Republicans do so for all four reforms.

Figure 2 provides considerable evidence that partisan self-interest shifts support (albeit modestly) for electoral procedures even when there are normative concerns about them. As previously noted, however, we asked respondents about the reforms identified by co-partisans as most unfair, regardless of whether they themselves believe these reforms are unfair. In doing so, we avoided an alternative approach of asking each subject about their perceived least fair proposals due to our concern that for policies rated unfair by few individuals we would have insufficient observations to analyze. That said, one might suspect that the Fig. 2 results are driven by those who did not rate the reform as unfair.

To assuage that concern, we replicate Fig. 2 after restricting the samples to those who rated the specific reform as unfair. Panel A of Fig. 3 shows that while the estimated treatment effects for this subset of Study 1 Democrats are slightly smaller than for all party members, the relationships observed in Fig. 2 persist. Democrats remain significantly more favorable toward a civics test (by 0.14 points, p = 0.04), purging registrants for inactivity (by 0.12 points, p = 0.04), and giving officials greater discretion to discard mismarked ballots (by 0.14 points, p = 0.02) when those disenfranchised are Republicans rather than co-partisans. Panel A also shows that Republicans behave similarly for all reforms, becoming more accepting of the reform they classified as unfair if adoption negatively affects Democrats vis-à-vis co-partisans (all p < 0.05).Footnote 15 These differences are roughly the same magnitude as those for the entire GOP sample. Across both parties then in Study 1, even those who believe a change is unfair (in the abstract) consistently appear more open to it when the policy enhances their team’s electoral prospects.

Effect of Partisan Treatments on Opposition to Election Reforms, Those Rating the Reform as Unfair. Note: Symbols are linear combination of coefficients tests for OLS regression model estimates of the effect of the “hurts team” compared to “helps team” treatments on election reform support (1 = strongly favor, 4 = strongly oppose). Range spikes are 90% confidence intervals

Panel B tells a more mixed story for Study 2 subjects. Whereas Study 1 Democrats who rated specific reforms as unfair expressed less opposition to the adoption of three of those four reforms when in their partisan self-interest, this is true for only one reform in Study 2. Specifically, Democrats are about one-fifth of a point less opposed to purging registrants for inactivity when those removed from the voter rolls are Republicans rather than co-partisans (p < 0.05). For requiring a civics test and giving officials more discretion to exclude mismarked ballots, Democrats become more supportive when the proposals enhance their electoral prospects, but neither difference is statistically significant (p = 0.15 and 0.12, respectively).

As in Study 1, Study 2 Republicans who evaluated individual policies as unfair nonetheless consistently report less opposition to them when framed as providing an electoral advantage. This is the case for a civics test (by 0.26 of a unit, p = 0.04), EDR (by 0.58 of a unit, p < 0.01), and a poll tax (by 0.16 of a unit, p = 0.04). The one exception is granting greater leeway to discard mismarked ballots. GOP members are less opposed to this proposal when framed as negatively impacting Democrats (compared to their party’s supporters), but unlike in Study 1 this effect is not statistically significant (0.18 of a unit, p = 0.11). Still, in seven of the eight analyses across studies, Republicans shift their support on policies they deemed unfair when they can gain electorally from their adoption. In contrast to what we observe for the entire sample, none of the treatment effects in either study cause mean attitudes to shift from oppose to support for those who view the reform as unfair.

One question that arises from comparing Panels A and B is why Study 2 Democrats do not as frequently shift their attitudes to the same degree as their Study 1 counterparts. This apparent inconsistency could be due to either experiment’s results not accurately reflecting how Democrats generally evaluate reforms or the different sample compositions. Another possibility, however, derives from Democratic attitudinal shifts being modest in size and fewer Study 2 Democrats rating each reform as unfair (which yields less precise treatment effect estimates). For example, the change in opposition to allowing officials to discard mismarked ballots depending on whose ballots are excluded is essentially the same in Studies 1 and 2 (0.14 and 0.15). The Study 1 sample consists of almost 300 more Democrats though, leading to standard errors almost half the size of those in Study 2. The effects for a civics test are also similar across studies (0.14 and 0.12), but the Study 1 standard errors are lower due to a sample size that is 1.5 times larger. Thus, while we fail to identify statistically significant relationships for Democrats as consistently in Study 2 as in Study 1, the results are substantively consistent with the story that Democrats, like Republicans, are more willing to adopt unfair reforms when that action improves their electoral prospects (even if that willingness, in terms of the magnitude of attitudinal shifts, is smaller than that for GOP supporters).

Treatment to Control Comparisons

As noted above, we examine the difference between the hurts and helps team treatments because likely pre-existing beliefs about a policy’s partisan consequences complicate the estimation of the effect of partisan self-interest when the control group is the comparison. One potential objection to this approach, however, is that the treatments may shift attitudes through distinct mechanisms (and thus cannot be compared to each other). Becoming more supportive of a reform when told it helps one’s team seems difficult to attribute to a factor besides electoral considerations, but becoming less supportive when told the policy hurts one’s team might not be driven by partisan self-interest. Instead, subjects may have simply updated their prior beliefs about the policy’s fairness (which in turn causes their support for the reform to drop).

While we cannot rule out that possibility, we note that our wave 1 fairness measurements of the reforms for which we gauge support in wave 2 use the exact same policy descriptions as the wave 2 control conditions. Those descriptions explicitly state that the reforms will cause some people to not vote/have their votes counted (or to vote in the case of EDR). As such, when evaluating each policy’s fairness subjects know that it will hinder the participation of some who are otherwise eligible and why it will do so (e.g., fail a civics test). If the hurts team treatments simply cause people to update their prior fairness assessments, then subjects must genuinely feel that, for example, prohibiting those who fail a civics test from voting becomes less fair when it turns out that those disenfranchised are their party’s people as opposed to just some people (of unknown partisanship). In reality this may occur to a degree, either because fairness and self-interest are not actually as distinct of concepts as the literature treats them or because people infer that they misunderstood the policy’s fairness after learning that co-partisans are disproportionately impacted (rather than presumably an equal proportion of partisans or primarily opposition supporters). But neither of those scenarios comports with (our reading of) how the literature treats the concept of procedural fairness.

That said, we generally observe partisan attitudes shift on the same set of policies (albeit more modestly as one would expect) when we instead compare the treatments to the control. For nine of the thirteen treatment to treatment statistically significant effects reported in Fig. 2, at least one of the treatments compared to the control is significant (p < 0.05, one-tailed): Study 1 Democrats and Republicans on voter purges and discarding mismarked ballots; Study 1 Republicans on a civics test; Study 2 Democrats and Republicans on discarding mismarked ballots; and Study 2 Republicans on EDR and a poll tax. The same is true for five of the eleven significant effects shown in Fig. 3: Study 1 Democrats on a civics test; Study 1 Democrats and Republicans on discarding mismarked ballots; and Study 2 Republicans on EDR and a poll tax. Those counts increase to eleven and nine, respectively, if we use a larger alpha of p < 0.1.Footnote 16

Furthermore, these comparisons reveal that treatment effectiveness varies considerably by party. Democrats appear primarily responsive to the helps team treatments, while Republican attitudes respond more strongly to the hurts team treatments. This heterogeneity may derive from the mechanisms noted above, meaning that when their self-interest is primed Democrats often shift their reform support to better align with it while Republicans generally do not (and just frequently update their fairness assessments). This pattern is also consistent though with our expressed concerns about the treatment to control group comparisons. Specifically, for members of both parties the more effective treatment is that which provides information counter to the reform’s likely actual consequences and (based on the separate MTurk study) the likely pre-existing beliefs for many subjects.

Does Perceived Fairness Condition Treatment Effects?

Finally, given that the treatment effect sizes are sometimes smaller for those who view the policy as unfair compared to all co-partisans, we investigate whether perceived fairness conditions the impact of the treatments on reform support. We re-estimate the entire sample models used to produce Fig. 2 but also include the wave one 7-point reform fairness rating and interact it with both treatments, party identification, and the treatment x party identification terms. The results (in Table S10) show that only one of the sixteen effects presented in Fig. 2 are significantly conditioned by fairness evaluations (for Study 1 Democrats on a poll tax; p < 0.05, two-tailed). Similarly, only one of the thirty-two interaction effects are significant if we instead focus on the treatment versus control comparisons (the hurts team poll tax treatment for Study 1 Democrats). As such, the willingness to temper opposition to reforms that fellow partisans deem unfair for electoral gain is not significantly conditioned by how unfair the individual herself or himself considers the policy.

Conclusion

Using multiple two wave panel studies, we show that partisans are more amenable to changing voting rules in a way that helps their team and handicaps the opposition, even on measures they previously saw as unfair. To be fair, the attitudinal shifts toward electoral advantage are often relatively modest off a high opposition baseline. The fact though that opinions move at all is surprising given that, while the procedural justice literature does allow for one’s fairness criteria to be subjective and potentially influenced to a degree by partisan considerations, once a process is judged to be unfair that judgment should remain relatively fixed. Our findings instead show at least some malleability in how citizens weigh fairness when evaluating election laws.

These results signal that arguments about the strength of citizen commitments to ideas of procedural fairness need further investigation. From our study fairness commitments do not appear completely resistant to the prospect of partisan gain, raising the possibility of social desirability bias in prior survey work on elections and processes where voters express the socially expected fairness concern when in fact considerations are more complex. We do not assess the relative weights assigned to these factors, and the modest-sized shifts toward seeking an electoral advantage signal fairness commitments still matter (in fact, fairness evaluations consistently predict reform support in the models assessing if fairness conditions treatment effects). Our results do align though with a growing body of work casting doubt on the primacy of procedural fairness (e.g., Esaiasson et al. 2019) and signaling that even citizens are influenced by winning above and beyond procedural fairness when it comes to evaluating decisions.

On the face of it, that Democrats (Republicans) are more supportive of electoral laws that benefit Democrats (Republicans) may not seem terribly surprising. But it is worth underscoring that our results strongly suggest that there is more going on than simply differing policy preferences. While Republicans are more concerned about electoral integrity and Democrats prioritize access, these differences in values and definitions of fairness do not explain our results. Rather, we demonstrate that, whatever definition of fairness voters hold, those beliefs do not preclude an increased willingness to adopt policies that violate that definition for political gain.

Our results pose several questions for further analysis. These include determining whether some voters are more tolerant of gamesmanship than others or if variations in framing (e.g., gains versus losses) invoke different responses.Footnote 17 Still unanswered is also the question of where the limits of any gamesmanship for voters lie (i.e., what types of reforms that they deem unfair are individuals unwilling to become even slightly more open to so as to advance their partisan interests). We did not ask about egregious examples such as vote buying, voter coercion, or simply forbidding people to vote because of their race, gender, or religion. Instead, the rule changes we tested were in what may be a greyer area of situations in which the voters asked about in our survey could be seen to have some choice: they could have voted given a willingness to pay a greater (time and/or financial) cost. Perhaps citizens are more tolerant of gamesmanship that still provides voters with some degree of agency or choice of behavior. We do not yet know at what point citizens decide “enough is enough” and judge reforms to have gone too far, but our current results signal that voters grant some leeway when it comes to what is seen to be, or rationalized as, acceptable in practice even after expressing doubts about it in principle. This study has begun to raise questions about the acceptability of political gamesmanship but further work is needed.

Notes

Replication materials can be found in the Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/XFCGKU.

Those potentially disenfranchised are described without information that might suggest their partisanship, signaling this effect is likely not due to electoral self-interest (though subjects may have prior beliefs about the partisanship of those impacted by ID laws).

SSI samples from a panel recruited through multiple methods (e.g., web advertising and phone and mail solicitations) and takes efforts to recruit those often underrepresented in online panels (e.g., racial and ethnic minorities and the elderly).

In Study 1, we used an attention screener to exclude subjects before they assessed reform fairness. We did not do so in Study 2. We thus address concerns about inattentive subjects by excluding the top five percent of subjects who completed the wave one survey the fastest.

Party identification is based on a seven point scale with Independent leaners treated as partisans (measured after assessing reform fairness). We consider a survey completed if the respondent reached the end of the survey. For Study 2, SSI recruited 1,010 subjects each who identified as Republican or Democrat when they registered with SSI. We exclude from our wave 2 analysis those who in wave 1 no longer identify with that party. See the Supporting Information for the survey instrument.

We report all wave one subjects’ evaluations, as those responses determined the policies asked about in wave two. Results are the same if we restrict evaluations to those successfully re-contacted for wave two (see Table S2).

In both studies, these are the four policies identified as the most unfair by party members except for purging registrants for inactivity among Study 1 Republicans (for whom it is the fifth most unfair proposal and EDR is the fourth).

Although related, our fairness and support measurements do not appear to capture the same concept. The correlation between fairness and control group support in Study 1 is .73 for a civics test, .63 for purging registrants for inactivity, .55 for a poll tax, and .45 for giving officials greater discretion to discard mismarked ballots. The correlations are lower in Study 2 (.38 to .56 for those policies and EDR).

Chi-squared tests from multinomial logit models used to assess imbalances across conditions by predicting treatment assignment as a function of measured covariates (age, gender, education, race/ethnicity, and political interest) are not significant for Study 1 questions for Republicans or Democrats (p-values between .08 and .95, average = .53). The same is true for Study 2 (p-values between .12 and .83, average = .41) except for the poll tax question for Democrats (p = .01). It is unclear why this imbalance occurred (other than random chance), but it does not lead to the identification of a significant relationship.

Pooling subjects yields four instances where a significant treatment effect is significant only for Republicans (see the replication materials).

Racial and ethnic minorities are disproportionately purged from voter rolls and were targeted with poll taxes to disenfranchise them (Keyssar 2009), while EDR may increase their turnout and/or that of other Democratic supporters (Hanmer 2009). The partisan impacts of imposing a civics test or giving officials greater discretion to reject mismarked ballots are less clear, though subjects may infer those implications from who they think are most likely to fail the test or improperly complete their ballot (e.g., those less educated or knowledgeable).

Tables S4-S7 report full model results for all estimated effects. Results are essentially the same when we include covariates (age, gender, education, race/ethnicity, political interest, and question randomization order) despite losing cases due to item nonresponse (see Tables S4-S7) or if we estimate ordered probit models (see Tables S8-S9). Tables S11.1–11.4 report survey marginals for partisans across treatments for all items in both studies.

The treatment effects for purging registrants for inactivity and a poll tax are statistically larger for Republicans than for Democrats (p < .05, two-tailed).

The poll tax treatment effect is larger than the effect for Democrats (p < .01, two-tailed).

The poll tax treatment effect is statistically larger for Republicans than for Democrats (p < .05).

See Tables S4-S7. The treatment coefficients are the effects for Democrats, while the linear combination of coefficient tests at the bottom of the tables report these effects for Republicans.

For example, one might suspect that the treatment effects vary across strength of party identification (such that e.g., only more committed partisans shift their support levels). Although we find no evidence for such heterogeneous effects, our sample sizes across different levels of partisan strength are potentially too small to detect any differential effects if they do in fact exist.

References

Alvarez, R. M., Hall, T. E., Levin, I., & Stewart, C., III. (2011). Voter opinions about election reform: Do they support making voting more convenient? Election Law Journal, 10(2), 73–87.

Anderson, C. J., Blais, A., Bowler, S., Donovan, T., & Listhaug, O. (2005). Losers’ consent. Oxford University Press.

Banducci, S. A., & Karp, J. A. (1999). Perceptions of fairness and support for proportional representation. Political Behavior, 21(3), 217–238.

Bentele, K. G., & O’Brien, E. E. (2013). Jim Crow 2.0? Why states consider and adopt restrictive voter access policies. Perspectives on Politics, 11(4), 1088–1116.

Berinksy, A. J., Huber, G. A., & Lenz, G. S. (2012). Evaluating online labor markets for experimental research: Amazon.com’s Mechanical Turk. Political Analysis, 20(3), 351–368.

Biggers, D. R. (2019). Does partisan self-interest dictate support for election reform? Experimental evidence on the willingness of citizens to alter the costs of voting for electoral gain. Political Behavior, 41(4), 1025–1046.

Biggers, D. R., & Hanmer, M. J. (2015). Who makes voting convenient? Explaining the adoption of early and no-excuse absentee voting in the American states. State Politics & Policy Quarterly, 15(2), 192–210.

Biggers, D. R., & Hanmer, M. J. (2017). Understanding the adoption of voter identification laws in the American states. American Politics Research, 45(4), 560–588.

Blais, A. (2000). To vote or not to vote. University of Pittsburgh Press.

Boix, C. (1999). Setting the rules of the game: The choice of electoral systems in advanced democracies. American Political Science Review, 93(3), 609–624.

Bowler, S., & Donovan, T. (2013). The limits of electoral reform. Oxford University Press.

Bowler, S., Donovan, T., & Karp, J. A. (2006). Why politicians like electoral institutions: Self-interest, values, or ideology? Journal of Politics, 68(2), 434–446.

Coppock, A., Leeper, T. J., & Mullinix, K. J. (2018). The generalizability of heterogeneous treatment effect estimates across samples. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(49), 12441–12446.

Doherty, D., & Wolak, J. (2012). When do the ends justify the means? Evaluating Procedural Fairness. Political Behavior, 34(2), 301–323.

Esaiasson, P., Persson, M., Gilljam, M., & Lindholm, T. (2019). Reconsidering the role of procedures for decision acceptance. British Journal of Political Science, 49(1), 291–314.

Fougere, J., Ansolabehere, S., & Persily, N. (2010). Partisanship, public opinion, and redistricting. Election Law Journal, 9(4), 325–347.

Gangl, A. (2003). Procedural justice theory and evaluations of the lawmaking process. Political Behavior, 25(2), 119–149.

Gerber, A. S., Green, D. P., & Larimer, C. W. (2008). Social pressure and voter turnout: Evidence from a large-scale field experiment. American Political Science Review., 102(1), 33–48.

Hajnal, Z., Lajevardi, N., & Nielson, L. (2017). Voter identification laws and the suppression of minority votes. Journal of Politics, 79(2), 363–379.

Hanmer, M. J. (2009). Discount voting. Cambridge University Press.

Hibbing, J. R., & Alford, J. R. (2004). Accepting authoritative decisions: Humans as wary cooperators. American Journal of Political Science, 48(1), 62–76.

Hibbing, J. R., & Theiss-Morse, E. (2002). Stealth democracy. Cambridge University Press.

Kane, J. V. (2017). Why can’t we agree on ID? Partisanship, perceptions of fraud, and public support for voter identification laws. Public Opinion Quarterly, 81(4), 943–955.

Karp, J. A., & Tolbert, C. J. (2010). Support for nationalizing presidential elections. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 40(4), 771–793.

Keyssar, A. (2009). The right to vote (Revised). Basic Books.

McCarthy, D. (2019). Partisanship vs. principle: Understanding public opinion on same-day registration. Public Opinion Quarterly, 83(3), 568–583.

Smith, D. A., Tolbert, C. J., & Keller, A. M. (2010). Electoral and structural losers and support for a national referendum in the US. Electoral Studies, 29(3), 509–520.

Tolbert, C. J., Smith, D. A., & Green, J. C. (2009). Strategic voting and legislative redistricting reform: District and statewide representational winners and losers. Political Research Quarterly, 62(1), 92–109.

Tyler, T. R. (1988). What is procedural justice? Criteria used by citizens to assess the fairness of legal procedures. Law and Society Review, 22(1), 103–136.

Tyler, T. R. (2006). Psychological perspectives on legitimacy and legitimation. Annual Review of Psychology, 57, 375–400.

Tyler, T. R., Casper, J. D., & Fisher, B. (1989). Maintaining allegiance toward political authorities: The role of prior attitudes and the use of fair procedures. American Journal of Political Science, 33(3), 629–652.

Wilking, J. R. (2011). The portability of electoral procedural fairness: Evidence from experimental studies in China and the United States. Political Behavior, 33(1), 139–159.

Wilson, D. C., & Brewer, P. R. (2013). The foundations of public opinion on voter ID laws: Political predispositions, racial resentment, and information effects. Public Opinion Quarterly, 77(4), 962–984.

Zink, J. R., Spriggs, J. F., & Scott, J. T. (2009). Courting the public: The influence of decision attributes on individuals’ views of court opinions. Journal of Politics, 71(3), 909–925.

Funding

Study 2 was funded by a grant provided by the New Venture Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Studies 1 and 2 were reviewed and approved by the University of California, Riverside (UCR) IRB Socio-Behavioral Committee (Protocol HS-17-016). The study of perceptions of the control condition prompts was ruled exempt by the UCR IRB Socio-Behavioral Committee (Protocol HS-20-189).

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in all studies.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Biggers, D.R., Bowler, S. Citizen Assessment of Electoral Reforms: Do Evaluations of Fairness Blunt Self-Interest?. Polit Behav 44, 435–454 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-021-09723-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-021-09723-9