Abstract

Elections are now a common feature of countries across regime types, yet we know little about what leads people to perceive an election as fair, or how the democratic context shapes the ingredients of fairness judgments. While the conduct of a process is most important for perceptions of fairness in established democracies, “procedural fairness” may not travel to non-democracies, where economic outcomes occasionally take precedence over procedure. Additionally, individual level characteristics, such as political engagement, may also shape how people view the fairness of elections. Using original experiments conducted in the United States and China, I find procedural considerations are most important for fairness judgments, across democratic contexts and largely independent of political engagement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Participation in elections is an experience increasingly shared by people in democracies and non-democracies (e.g., Schedler 2002a; Diamond 2002; Levitsky and Way 2002), and whether individuals feel they are treated fairly or unfairly in an election can have important political consequences. When people feel they are treated fairly by government, they are more trusting and satisfied (Mishler and Rose 1997, 2001a; Levi 1998; Craig et al. 2006), and the overall legitimacy of government is enhanced (Banducci and Karp 1999; Weatherford 1992). Conversely, when people feel they have been treated unfairly by government authorities, they are less likely to comply with laws and policies (Tyler 1990; Tyler and Rasinski 1991; Brockner et al. 1992), less likely to vote (Birch 2005), and more likely to protest (Lober 1995; Pastor 1999; Schedler 2002b). Perceptions that elections are conducted fairly are especially important in non-democracies experimenting with elections, as initial impressions of democratic institutions may shape how people feel about democracy as a system of government more generally.

Despite the important implications of perceptions of election fairness, we know relatively little about what shapes fairness judgments (as exceptions, see Birch 2008; Norris 2002, 2004). Extensive evidence of “procedural fairness” in the judicial and organizational domains suggests that procedures may affect assessments of fairness in the political domain. I explore the effects of three procedural characteristics of elections—participation (“voice”), equal treatment, and nomination procedures (“choice”), to see if procedural fairness also exists in the context of elections. In addition, whether a desired end or outcome is received has been shown to affect judgments of election fairness and other processes, as well as evaluations of government more generally (Anderson et al. 2005; Skitka et al. 2003; Mishler and Rose 1997, 2001a, b, 2002). For these reasons, I also explore the effects of electoral and economic outcomes on fairness judgments.

Additionally, whether a person feels an election is fair or unfair, may depend upon where they are standing on election day—in a democracy or non-democracy. Democracies appear to emphasize procedure to a greater extent than non-democracies, while some non-democracies prioritize economic development and economic outcomes. I assess three theoretically feasible ways by which procedure, outcome, and context may affect fairness judgments. First, the specific procedural characteristics of an election that determine fairness judgments may vary across democratic and non-democratic contexts (Hypothesis 1). Second, outcomes may be most important in a non-democracy, while the procedural conduct of the election may be most important in a democracy (Hypothesis 2). Third, procedural characteristics may be the dominant explanation across contexts, but may be relatively less important in a non-democracy (Hypothesis 3).

Finally, it is also possible that in addition to the broader political context, some individuals are more likely than others to perceive the election as fair, and to place more importance on the procedural conduct of the election. People who are more trusting and politically engaged are more positive about government (e.g., Levi and Stoker 2000) and participatory (e.g., Verba et al. 1995), and these individuals may be more likely to perceive an election as fair (Hypothesis 4). The politically engaged may also pay more attention to and care more about the procedural conduct of an election, so that the procedural characteristics have larger effects among more engaged individuals (Hypothesis 5).

Original data from experiments conducted in the United States and China allow a series of “horse races” between various procedural aspects of elections, on the one hand, and outcomes on the other hand. Overall, the results are most supportive of Hypothesis 3—the procedural characteristics are most important for perceptions of fairness, but have consistently smaller effects in China compared to the United States. These findings have important real world implications. The fact that perceptions of electoral fairness are primarily procedurally determined suggests that both democratic and non-democratic governments must pay attention to how political processes are conducted, rather than relying on economic development or a core of politically engaged individuals to generate legitimacy.

Explanations of Perceptions of Election Fairness: Means and Ends

Why do people feel an election is fair or unfair? Two distinct, election-related factors may matter for fairness judgments: procedural characteristics of the election and whether the election produces a desired outcome.

The procedural justice literature, set predominantly in the contexts of the courts and organizations, finds two characteristics of a process consistently affect judgments the process is fair: the degree to which an individual is able to express him or herself in the course of a process (“voice”) (e.g., Thibaut and Walker 1975; Lind et al. 1983, 1990), and whether individuals are treated in an equal manner to all others (“equal treatment”) (e.g., Lind and Tyler 1988; Tyler 1989). In the context of elections, “voice” can be re-cast to refer to whether an individual was able to participate in the election, and “equal treatment” to whether all individuals have equal influence. In addition to these characteristics transported from the judicial context, elections often range in the quantity and quality of alternatives available to individuals (e.g., Diamond 2002; Wessels and Schmitt 2008), and this is directly affected by how candidates are nominated (e.g., Kennedy 2002). Thus, the nature of “choice” (captured by nomination processes) may also affect perceptions of electoral fairness.

In politics, individuals also care deeply about ends and these can affect their evaluations of political processes. At least two types of outcomes may affect perceptions of fairness.Footnote 1 First, an electoral outcome concerns whether an individual’s preferred candidate is elected. “Winners,” in this sense, are slightly more likely than “losers” to perceive a process as fair (Anderson et al. 2005, 41), and more likely to have positive attitudes toward government (Miller 1974; Baloyra 1979; Anderson et al. 2005; Moehler 2009). Second, people may also consider the state of the economy. Evaluations of the economy affect candidate choice (e.g., Kinder and Kiewiet 1981), and broader attitudes toward government, across established and new democracies (e.g., Weatherford 1984, 1987; Mishler and Rose 2001b). Thus, individuals may also consider an economic outcome—meaning expectations of how their preferred candidate will affect the economy—in their evaluations of electoral fairness.

Different Contexts, Different Effects?

Whether a person pays more attention to the conduct of an election or the outcome of an election may be shaped by whether they reside in a democracy or non-democracy. In the section below, I discuss several ways in which the effects of procedural characteristics and outcomes might vary across contexts, specifically across the U.S. and China.

Which Procedural Characteristics, and Where?

First, the relative effects of different procedural characteristics (in this case, voice, equal treatment, and choice) may depend upon the extent to which each characteristic is embedded in the broader institutions of the country, and may thus vary across democratic and non-democratic regime types.

Most broadly, principles of voice or participation, equality, and choice, are instilled in the institutions of democratic regimes, but are less likely to be found in the institutions of non-democracies. For example, voice is fostered in democracies through rights guaranteeing free speech and association, but principles of participation or voice in non-democracies are qualitatively different. Mass participation in totalitarian regimes is aimed toward furthering and enforcing the ideology handed down by the leadership (Linz 1975/2000, 71), and “voice” in opposition to the leadership is often silenced through the use of force or terror (111).

As an established democracy, the United States fits this characterization of a democratic regime. Principles of voice are instilled through regular elections and a vibrant civil society, while the commitment to equal treatment is institutionalized in the fifteenth and nineteenth amendments to the constitution guaranteeing universal suffrage. The commitment to “choice” is evident in open nomination procedures. Thus, we might expect each of the identified procedural characteristics to explain perceptions of fairness in the United States.

With respect to two of the three procedural characteristics, voice and choice, China fits the preceding categorization of non-democracies. Institutions that facilitate voice are weak or compromised in China. For example, the Chinese government provides opportunities for expression through complaint bureaus to which citizens can express their dissatisfaction (see Luehrmann 2003), but limits on free expression institutionalized in the constitution (Lieberthal 1995, 357) and criminal code (Eliasoph and Grueneberg 1981, 677) hamper the effectiveness of the complaint bureaus. “Choice” is similarly limited in China. While direct elections for the lower levels of leadership exist, candidates for the local level People’s Congresses are selected by the party (McCormick 1996), leading Shi (1999) to classify these elections as “limited choice elections.”

While lacking voice and choice, China has historically shown some commitment to equal treatment. Equalization of status and income were a fundamental theoretical tenet of Communism, as practiced under Mao (1949–1976). However, the theory and practice of equality in China diverged both during and after Mao’s time; Mao’s policies contributed to urban/rural inequalities (Whyte 2010) and these inequalities have only increased with the transition to the market economy (Khan and Riskin 1998, 2005). Although de facto income inequality is an historic and contemporary reality in China, the past ideological emphasis on egalitarianism may make this procedural characteristic especially salient among the Chinese sample. Thus, the procedural ingredients of perceptions of electoral fairness may differ across the cases, such that equal treatment will have comparable effects across the cases, but voice and choice will have smaller effects in China compared to the United States (Hypothesis 1).

Procedural Characteristics and Outcomes Across Contexts

Second, context may also condition the relative importance of the procedural and outcomes-based explanations, especially with respect to economic outcomes. Painting with broad brush strokes, democracies appear to place more emphasis on the existence and systematic implementation of procedures than non-democracies, and some non-democratic regimes appear to prioritize economic development (and thus providing economic outcomes), over attention to political processes. For example, democratic regimes are more likely than non-democratic regimes to institute rule of law legal systems, which dictate the equal treatment of all individuals under the law (Carothers 1998, 97). Additionally, some non-democracies appear to view this lack of emphasis on procedure as necessary to achieve economic development, based on the idea that political competition can hamper development (Huntington 1968; Huntington and Dominguez 1975).Footnote 2 These differences in emphasis may be passed down to individuals in their political experiences with a regime, and thus might condition how individuals view the fairness of a local election.

Although oversimplified, this characterization fits the cases reasonably well. To the end of promoting economic development, the Chinese government has disproportionately reformed the economic system over the political system in the last 30 years (Zheng 1994). These efforts have been successful, resulting in 9% average yearly GDP growth and substantial improvements in living standards (Heston et al. 2006; UN Human Development Report 2005, 226). When political reforms have occurred, such as the promotion of the rule of law, the motivation and purpose of the reforms have been largely instrumental—to further or quicken economic development (Pei 1995, 67). Additionally, some public opinion data suggest that the prioritization of economic outcomes over political reforms extends to the mass level (Tang 2005, 60).Footnote 3

These different emphases across the cases could theoretically affect the relative ingredients of perceptions of electoral fairness in two ways. First, these differences may be extreme enough so that receipt of an economic outcome is most explanatory in China, while procedural characteristics are most important for perceptions of fairness among U.S. respondents (Hypothesis 2). Alternatively, procedural characteristics may be the predominant explanation across both contexts, but may have a smaller effect in China relative to the U.S. (Hypothesis 3).

Are the Politically Engaged Different?

In addition to the larger political context affecting perceptions of fairness, it is also conceivable that individual level factors explain perceptions of fairness. Specifically, people who are more politically engaged—conceptualized here by political trust, political interest and efficaciousnessFootnote 4—may be more likely than others to perceive an election as fair. Politically trusting individuals are more likely to positively evaluate political actors and institutions, and are more participatory (e.g., Muller and Jukam 1977; Sigelman et al. 1992; Hetherington 1998; Levi and Stoker 2000). Similarly, interest in politics, feelings the government is responsive (external efficacy), and confidence that one can understand politics (internal efficacy), also increase political participation (Verba et al. 1997; Burns et al. 2001). Given the positive effects of political engagement on other behaviors and attitudes, it is theoretically possible that politically engaged individuals will more positively evaluate the fairness of elections (Hypothesis 4). Additionally, politically engaged individuals may also pay more attention to and care more about the procedural conduct of an election than the less engaged. If this is the case, the procedural characteristics may have a larger effect on fairness judgments among the politically engaged, compared to the less engaged (Hypothesis 5).Footnote 5

Experimental Method

To test the effects of procedural characteristics, outcomes, the democratic context and political engagement on perceptions of fairness, I conducted experimental studies using student subjects at three universities in Tianjin, China and in the United States, at the University of California, Davis, during the 2007–2008 academic year.Footnote 6

The use of the experimental method and university student subjects is appropriate to achieving a primary goal of the paper: to establish whether, and how, the effects of procedural characteristics and outcomes differ across democratic contexts. First, the experimental method maximizes internal validity, and thus we can be confident the intentional manipulations of procedure and outcome are responsible for the attributed effects (Kinder and Palfrey 1993; McDermott 2002a, b). Second, although students may differ from the general populations in both cases, U.S. and Chinese students have vastly different experiences having grown up in democratic and non-democratic regimes. This paper takes advantage of these differences to determine how regime type may shape the ingredients of perceptions of fairness.

Treatments

The experimental treatments were administered to subjects in a series of hypothetical scenarios. Hypothetical scenarios are commonly employed in procedural justice research (Thibaut and Walker 1975, chapter 8; Lind et al. 1978), and are similar to vignettes, in which a subject reads a story about another person (e.g., Duch and Palmer 2004; Gibson 2002; Gibson and Gouws 1999). In this study, the scenarios asked subjects to imagine themselves in a hypothetical local election (a village election in China, and a city council election in the United States). Subjects read a total of five scenarios, four of which are relevant to this paper: a “voice” scenario, “equal treatment” scenario, “choice” scenario, and “economic outcome” scenario. Prior to reading any scenarios, respondents answered a pre-test questionnaire, which included measures of political engagement and a distractor task. An identical post-test followed each scenario.

Each scenario manipulates two elements of the election: a procedural characteristic and an outcome, resulting in four versions of each scenario. Each respondent received one of the following four versions of each scenario, for a total of four scenarios: version A in which a procedural characteristic is present and an outcome is positive, version B in which the procedural characteristic is present and the outcome is negative, version C in which the procedural characteristic is absent and the outcome is positive, and version D in which the procedural characteristic is absent and the outcome is negative. Table 1 portrays these general treatments.

The procedural characteristics and outcomes were represented in the scenarios in the following ways. “Voice” was captured by whether or not the individual was able to participate in the hypothetical election. “Equal treatment” was measured by whether the subject received an equal number of ballots as all other voters, and “choice” was represented by the nomination procedure used in the election; candidates were said to be either nominated through an open nomination process or were selected by the government. The voice, equal treatment and choice scenarios were each paired with an electoral outcome—represented by whether the respondent’s preferred candidate was elected. As an example, the voice and electoral outcome manipulations result in the following four versions of the voice scenario: the respondent was able to participate and their preferred candidate was elected (A); the respondent was able to participate, but their preferred candidate was not elected (B); the respondent was not able to participate, but their preferred candidate was elected (C); the respondent was not able to participate and their preferred candidate was not elected (D).

To measure an economic outcome, the economic outcome scenario links the electoral outcome to the economic well-being of the community, as well as the respondent’s hypothetical small business. In addition to this outcomes-based manipulation, a procedural component of the hypothetical election, combining elements of voice and equal treatment, is also varied across the versions of the economic outcome scenario. The first version (A) of the economic outcome scenario received by the Chinese sample is presented belowFootnote 7:

Imagine you are voting in your village committee election. When you arrive at the polling place, the lines to vote are short and you are able to vote in the election, along with all of the other village residents. Your preferred candidate for the committee chair has been the leader of the committee for several years, and has been successful in increasing the economic prosperity of those in the village. Along with the rest of the village, your small business has prospered in recent years and your personal income has increased. Several hours after voting, you hear that this candidate was re-elected to the committee! In the election, all village residents had an equal opportunity to voice their preferences, and the committee chair was re-elected. You expect the village to continue to prosper economically under his leadership.Footnote 8

In the unequal voting versions of the economic outcome scenario (C&D), participants in the hypothetical scenario were among a group of voters unable to vote due to long lines. In the negative outcome versions (B&D), the preferred candidate is not elected, and the scenario stipulates that the prosperity of the community may suffer.

The realism of the manipulations was maximized as best as possible across the two starkly different contexts. In China, all of the procedural manipulations are plausible, due to the variance in implementation of village elections (e.g., Hu 2005, 433; Pastor and Tan 2000). Additionally, that the economic well-being of a village and the individuals therein could be caused by the election of a specific village committee chair is also realistic in China. The Chinese media regularly report stories of model villages in which elected village committees successfully developed the economy of the village. The majority of the manipulations are also plausible in the United States, where some voters were denied the opportunity to vote in the 2004 presidential elections due to long lines at polling stations.Footnote 9

Assignment of Treatments

The versions of each scenario were assigned to subjects with the stipulation that a subject could not receive the same version (see Table 1) across the scenarios. For example, if a subject received version A of the voice scenario, in which she was able to vote and had her preferred candidate elected, this subject would not receive version A of the equal treatment scenario, in which she was given an equal number of ballots as other participants and received her desired electoral outcome. If a subject received version A of one scenario, the subject could not receive version A of any other scenario. While this rule prevents the individual versions of each scenario from being truly randomly assigned, the possible combinations or “bundles” of scenario versions were randomly assigned to respondents. For example, possible combinations of treatments include: Voice (A), Equal Treatment (B), Choice (C), and Economic Outcome (D), or, alternatively, Voice (D), Equal Treatment (A), Choice (B), and Economic Outcome (C).Footnote 10

Independent Variables

I create dummy variables for the procedural characteristics and outcomes of interest by combining the treatment groups in which the variable of interest is present. For example, to construct the equal treatment dummy variable, I combine the dummies for treatment groups A and B of the equal treatment scenario, as both of these groups received the manipulation in which all people received an equal number of ballots. To construct the electoral outcome dummy for the equal treatment scenario, I combine the dummy variables for treatment groups A and C of the equal treatment scenario, as the electoral outcome is positive in both of these versions.

I measure political engagement with questions regarding political trust, interest, and internal and external efficacy. The political trust question asks “How much of the time do you think you can trust the government in Beijing/Washington D.C. to do what is right?”, and ranges from 0 to 3 (with 3 being the most trusting). Political interest is measured with a question asking respondents how often they follow politics, and ranges from 0 to 4, with four being the most interested. To measure internal and external efficacy, respondents rate their level of agreement with the following statements, “Politics and government sometimes appears so complicated that it is difficult to understand how it is running” and “People like me don’t have any say in what government does.” Both efficacy measures range from 0 to 4, with four being most efficacious. In addition to including these measures in Model 2, I also interact each measure of political engagement with each procedural characteristic to test the potential conditioning effects of political engagement, in Model 3.

Dependent Variable

The dependent variable, perceptions of fairness, is measured by a question asking respondents, “Given this hypothetical scenario… How fair was the election?” The variable ranges from 0 to 10, with the end points labeled very unfair (0) and very fair (10).

Results

Voice, Equal Treatment and Choice Across Contexts (Hypothesis 1)

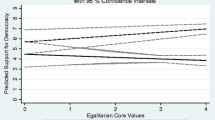

Hypothesis 1 asserts that the democratic context influences the extent to which each procedural characteristic explains perceptions of fairness. If the effects of the procedural characteristics depend upon prior exposure and familiarity, we would expect voice and choice to have smaller effects in China than in the U.S., while equal treatment should have the same effect across cases. As a first look, Figs. 1, 2, and 3 provide the mean levels of perceptions of fairness by scenario for both samples.

Figures 1, 2, and 3 demonstrate a main effect for the procedural manipulations across both samples, as mean perceptions of fairness decline most markedly when one moves from the treatment groups in which the procedural characteristic is present (A&B) to the groups in which the procedural characteristic is lacking (C&D), suggesting a strong effect for the procedural manipulations. However, this effect appears to be smaller among the Chinese sample for all three procedural characteristics; the means for treatment groups A&B are smaller among the Chinese sample, and the means among this sub-sample for groups C&D, in which the procedural characteristic is absent, are equal to or greater than the means for the U.S. sample for the voice and equal treatment scenarios. Counter to the expectation of Hypothesis 1, this suggests there is a smaller effect of all three procedural characteristics among the Chinese sample, rather than only voice and choice having smaller effects in China.

To assess the relative effects of the procedural characteristics through another lens, I present OLS regression results for the voice, equal treatment and choice scenarios in Model 1Footnote 11 of Tables 2, 3, and 4.Footnote 12

I interact each of the procedural and outcome variables with a country dummy representing the Chinese respondents. Each interaction and the individual components are included in the regression analyses. With the exception of the choice scenario, each procedural characteristic has a significantly smaller effect among the Chinese sample relative to the U.S. sample, as indicated by the negative and significant coefficient on the interactions between the China country dummy and the procedural characteristics. For example, equal treatment increases perceptions the process is fair by 7.09 points among the U.S. sample, and by 4.66 points among the Chinese sample. The fact that all three procedural characteristics, including equal treatment, have a significantly smaller effect in China disconfirms Hypothesis 1.

Relative Effects of Procedural Characteristics and Outcomes (Hypotheses 2 and 3)

While context does not appear to affect which procedural characteristics are important for perceptions of fairness, the regime type does condition the relative effects of the procedural characteristics and outcomes. Recall, this conditioning effect is hypothesized to take one of two forms. Hypothesis 2 states that procedural characteristics will be most important in a democracy, while economic outcomes will be most important in a non-democracy (H2). Hypothesis 3 asserts that procedural characteristics will be most explanatory of fairness judgments, but will have a smaller effect in China relative to the U.S. (H3).

The results provided in Figs. 1, 2, 3, and 4 and Tables 2, 3, 4, and 5 disconfirm Hypothesis 2, and provide the most support for Hypothesis 3.

Procedural characteristics have the largest substantive effects on perceptions of fairness, eclipsing the effects of both electoral and economic outcomes. However, with the exception of choice, each procedural manipulation has a smaller effect among the Chinese sample relative to the U.S. sample.

For example, the procedural manipulation in the economic outcome scenario, having an equal opportunity to vote, increases perceptions of fairness by 4.83 points along the 11 point scale for U.S. respondents. This is nearly half the distance of the scale, and a very large substantive effect for this characteristic of the process. Equal voting also has a large substantive and significant effect among the Chinese sample, moving respondents 3.1 points up the perceptions of fairness scale. Among both Chinese and U.S. respondents, receiving an economic outcome has a smaller, but significant effect relative to that of the procedural manipulation. Receiving a positive economic outcome increases perceptions of fairness by 0.95 points among the U.S. sample, and by 1.55 points among Chinese respondents. These findings are substantiated by the results for the voice, equal treatment and choice scenarios. Thus, while each procedural characteristic has a positive, significant and substantively much larger effect than that of an outcome across both samples, the procedural characteristics have consistently smaller (and significant) effects among the Chinese sample relative to the U.S. sample.

Effects of Political Engagement (Hypotheses 4 and 5)

In addition to the broader political context shaping perceptions of fairness, I also explore the possibility that political engagement, both directly and indirectly, affects perceptions of fairness. The political engagement variables are added in Model 2 of Tables 2, 3, 4, and 5 to test the hypothesis that the politically engaged are more likely to perceive the election as fair (H4). Three of the four measures of political engagement—political trust, interest and internal efficacy—achieve statistical significance in the expected directed, but inconsistently across the scenarios. Political trust increases perceptions of fairness by 0.56 points for the voice scenario and 0.32 points for the equal treatment scenario. Internal efficacy increases fairness judgments by roughly 0.15 points for the voice scenario, and 0.13 points for the economic outcome scenario. Finally, political interest increases fairness judgments by 0.37 points for the choice scenario. That at least one measure of political engagement is significant across all four scenarios provides some support for the hypothesis that the politically engaged are more likely to perceive the election as fair. However, relative to the procedural manipulations, which consistently increase fairness judgments by at least two points, political trust, interest and internal efficacy have much smaller substantive effects.

In addition to these direct effects, political engagement may also boost or enhance the effects of the procedural characteristics on perceptions of fairness. To explore this possibility, I interact each procedural characteristic with each individual characteristic, and split the samples by country. The results are provided in Model 3 of Tables 2, 3, 4, and 5. Among the U.S. sample, voice and choice have larger effects for the politically interested (Model 3, Tables 2 and 4), and equal voting has the largest effect among the internally efficacious (Model 3, Table 5). For example, the predicted values indicate that among the least politically interested, perceptions of fairness increase from 4.15 points when voice is absent to 7.65 points when voice is present—an effect of 3.5 points. Among the most politically interested, perceptions of fairness increase from 3.07 to 8.25 points across the voice conditions—an effect of 5.18 points. Among the Chinese sample, political trust has a similar effect for equal treatment, and voice (at p < 0.1) (Model 3, Tables 2 and 3). For example, for the least trusting, equal treatment moves perceptions of fairness less than 3 points, from 3.06 to 5.93 points. Among those with the highest levels of political trust, equal treatment moves perceptions of fairness almost six full points from 2.19 to 8.15.Footnote 13 These limited findings show that political engagement can have both direct and indirect effects on fairness judgments.

Discussion: External Validity and Student Subjects

These findings suggest that people care about the procedural conduct of an election, largely independent of whether they reside in a democracy or non-democracy, or are politically engaged. Prior to discussing the potential implications of these findings, the issue of external validity warrants further discussion.

To what extent can we generalize from these results based on student samples? Specifically, the most common question to put to this type of study is the following: should we expect that adults in the broader United States and China populations will behave in a similar way to the student samples and place the most importance on the procedural conduct of an election when considering whether an election is fair? To be clear, my primary goal is to establish causal relationships, rather than to generalize from these findings. And, as McDermott (2002b, 40) aptly notes, we only know with certainty whether results from any observational study are generalizable through replication. With these caveats, I speculate on what we might find among a non-student sample, by first identifying relevant differences between students and the general population and reflecting on how these difference might influence the results (as recommended by Kam et al. 2007, 421), and second, by looking to relevant empirical evidence based on non-student samples.

College students differ from the general population in one potentially important way—life experience. Students are younger and thus have fewer life experiences in general (Sears 1986), and less experience voting in elections (Miller and Krosnick 2000). For this reason, adults in both the United States and China may have a better understanding of the implications of both election procedures and outcomes than students. An election outcome can have personal and policy-related consequences, and the way in which an election is conducted can directly affect the election outcome. The greater awareness of these consequences among adults may lead adults in both the U.S. and China to place more emphasis on both the procedural characteristics and outcomes of an election, compared to a student sample. Given this difference, it is reasonable to expect the same pattern of results among a non-student sample, just larger effects of both the election procedures and outcomes.

In addition to considering differences, one similarity between the Chinese student and general population is notable. The student-led democracy movement in China during the late 1980s might lead some to assume university students are more interested in democratic reform than the general Chinese public—a difference that would have important implications for the broader applicability of my findings. However, some survey research indicates that this is not the case. University students and adults in China similarly prioritize economic growth over democratic reforms (see Tang 2005, 60; Zhao 2002, 900). Thus, there is further reason to expect the results would not differ widely across Chinese students and non-students.

The relevant empirical evidence, based on U.S. and Chinese adults, also suggests that, like the student samples, adults in these countries will value the procedural conduct of an election. For example, residents of Chicago place the most importance on procedural aspects of their interactions with authorities when judging the fairness of police or judicial processes (Tyler 1989). Additionally, in China, villagers regularly take political action when village elections are procedurally compromised (see O’Brien and Li 2006, 56–57). Based on this evidence, and the lack of obvious differences between students and non-students that might change the results of my studies, I would not expect to find markedly different findings among non-student samples. To reiterate though, these are tentative speculations on external validity, and replication with a non-student sample is a necessary and worthy next step.

Conclusions

The primary goals of this paper have been to establish the determinants of perceptions of electoral fairness across democratic contexts and individuals. Broadly, these results suggest electoral fairness means the same thing across contexts and the politically engaged; in both the United States and China, and among the least and most engaged, perceptions of electoral fairness are primarily explained by characteristics of the process rather than receipt of a desired outcome. Thus, “procedural fairness” appears to be a portable concept—to the process of elections, across democratic contexts and across individuals with different characteristics. Additionally, this paper has shown the specific ways in which the ingredients of perceptions of electoral fairness vary across contexts and individuals. Each procedural characteristic examined has a consistently smaller effect in a non-democracy relative to a democracy. Less consistently, selected dimensions of political engagement increase the effects of some of the procedural characteristics.

When an election (or other government process) is perceived as unfair, people are less likely to comply with laws and policies, more likely to protest, and the legitimacy of the government is generally diminished (e.g., Tyler 1990; Pastor 1999; Weatherford 1992). These findings suggest a clear avenue for leaders to prevent these negative consequences: insure elections are conducted in ways that maximize the participation of all citizens, from nomination to voting procedures. Emphasizing just economic development, or economic development at the expense of attention to political processes, may not be a winning long term strategy for government stability. Additionally, superficial elections, or elections without voice, equal treatment or choice, will be insufficient to generate government support. Rather, to have a legitimizing effect, elections must be procedurally fair.

Notes

While it may seem self-evident that the fairness of a process will be explained by procedural characteristics, this cannot be assumed, as outcomes have been found to explain a variety of attitudes including perceptions of fairness, across democratic contexts (e.g., Anderson et al. 2005; Mishler and Rose 1997, 2001a, b, 2002).

Empirical research has failed to clearly support this theoretical relationship between authoritarianism and economic development, or any relationship between regime type and economic growth (see Przeworski and Limongi 1993).

However, this characterization of China is certainly too simplistic. While economic development and economic reforms to achieve it has been a primary emphasis of the regime, this has not also meant an inattention to political procedures. With the economic reforms have also come important political reforms, such as village elections and direct election of local level People’s Congress deputies. Additionally, combating corruption has become a central focus of the regime, as seen in institutional changes as well as highly publicized anti-corruption campaigns (He 2000).

There is no theoretical reason, or empirical evidence to suggest that the effects of political engagement will depend upon the democratic context. While levels of political trust and engagement vary across established and post-Communist democracies (Mondak and Gearing 1998), across institutional contexts (Anderson and Guillory 1997; Miller and Listhaug 1990), and by levels of corruption (Anderson and Tverdova 2003; Andrain and Smith 2006), the positive effects of political engagement appear to remain constant across both new and established democracies (e.g., Norris 2004, chapters 5 and 7).

In China, the study was conducted at Nankai University, Tianjin University and Tianjin Agricultural College in October of 2007. Of the 846 subjects in the sample, roughly 200 are undergraduates at Tianjin Agricultural College, 86 are undergraduates from Tianjin University, 100 are graduate students at Nankai University, and 465 are undergraduates at Nankai University. The studies were administered in primarily general education classes. In the United States, these data were collected in the Political Science experimental laboratory at the University of California, Davis during May of 2008. Research subjects were drawn from both lower and upper division Political Science courses. A total of 497 subjects participated in this component of the study.

This is an English translation of the scenario received by Chinese respondents, in Mandarin.

Treatment schematics for each scenario, the text of all versions of each hypothetical scenario, and the pre-test and post-test questionnaires are all available on request from the author.

One might object that the unequal versions of the equal treatment scenario—in which some voters are provided more ballots than others—are relatively less credible in the United States. However, the notion of multiple votes has appeared in discussions in the media with respect to electronic voting machines, and therefore, the scenario may be within the realm of possibility for many subjects. Additionally, if U.S. subjects perceive the unequal ballots prompt as unlikely, and thus respond in a socially acceptable way, this reaction is theoretically interesting and consistent with the arguments of this paper. Specifically, principles of equal treatment are deeply embedded in the institutions of the United States, and contribute to a strong ethos of equality. Any socially acceptable responses provided by U.S. respondents are likely a reflection of this ethos.

Among the Chinese sample, there were 8 possible combinations of the four treatments, randomly assigned to respondents. The administration of the study in the experimental laboratory in the U.S. allowed for greater complexity, and 24 possible combinations of treatments were randomly assigned to U.S. respondents. However, the order in which the scenarios were received (e.g., voice, equal treatment, choice, economic outcome) was held constant across the cases. Additionally, the ratio in which one version was received first is the same across the U.S. and Chinese samples. For example, version A, in which the procedural characteristic is present and the outcome is positive, is received as the first version for ¼ of the U.S. sample and for ¼ of the Chinese sample. For these reasons, this variation in the research design across the cases is not likely to affect the results presented herein.

To check for possible interactive effects between the procedural characteristics and outcomes, I also estimated models which included interactions between each procedural characteristic and outcome, as well as a triple interaction between the procedural characteristic, outcome and country dummy. The substantive effects of the procedural characteristics, outcomes and interactions with the country dummies, are largely unchanged compared to the results presented in model 1. Results of these analyses are available on request from the author.

Given the nature of the dependent variable, OLS regression is an appropriate estimator. Each scenario is analyzed separately, because as previously mentioned, the versions of each scenario were assigned to respondents with the rule that a respondent could not receive similar versions of each scenario. For this reason, all three procedural characteristics cannot be included in the same regression analysis.

These are predicted values for perceptions of fairness, when all other variables are held at their means, and the outcome is positive.

References

Anderson, C. J., Blais, A., Bowler, S., Donovan, T., & Listhaug, O. (2005). Loser’s consent: Elections and democratic legitimacy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Anderson, C. J., & Guillory, C. A. (1997). Political institutions and satisfaction with democracy: A cross-national analysis of consensus and majoritarian systems. American Political Science Review, 91, 66–81.

Anderson, C. J., & Tverdova, Y. (2003). Corruption, political allegiances, and attitudes toward government in contemporary democracies. American Journal of Political Science, 47, 91–109.

Andrain, C. F., & Smith, J. T. (2006). Political democracy, trust, and social justice. Boston: Northeastern University Press.

Atkeson, L. R. (2003). Not all cues are created equal: The conditional impact of female candidates on political engagement. The Journal of Politics, 65, 1040–1061.

Baloyra, E. A. (1979). Criticism, cynicism, and political evaluation: A Venezuelan example. The American Political Science Review, 73, 987–1002.

Banducci, S. A., & Karp, J. A. (1999). Perceptions of fairness and support for proportional representation. Political Behavior, 21, 217–238.

Birch, S. (2005). Perceptions of electoral fairness and voter turnout. Presented at the American Political Science Association Annual Meetings. Washington, D.C.

Birch, S. (2008). Electoral institutions and popular confidence in electoral processes: A cross-national analysis. Electoral Studies, 27, 305–320.

Brockner, J., Tyler, T. R., & Cooper-Schneider, R. (1992). The influence of prior commitment to an institution on reactions to perceived unfairness: The higher they are, the harder they fall. Administrative Science Quarterly, 37, 241–261.

Burns, N., Schlozman, K. L., & Verba, S. (2001). The private roots of public action: Gender, equality and political participation. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Carothers, T. (1998). The rule of law revival. Foreign Affairs, 77, 95–106.

Craig, S. C., Martinez, M. D., Gainous, J., & Kane, J. G. (2006). Winners, losers, and election context: Voter responses to the 2000 presidential election. Political Research Quarterly, 59, 579–592.

Diamond, L. (2002). Thinking about hybrid regimes. Journal of Democracy, 13, 21–35.

Duch, R. M., & Palmer, H. D. (2004). It’s not whether you win or lose, but how you play the game: Self-interest, social justice, and mass attitudes toward market transition. American Political Science Review, 98, 437–452.

Eliasoph, E. R., & Grueneberg, S. (1981). Law on display in China. The China Quarterly, 88, 669–685.

Gibson, J. L. (2002). Truth, justice and reconciliation: judging the fairness of amnesty in South Africa. American Journal of Political Science, 46, 540–556.

Gibson, J. L., & Gouws, A. (1999). Truth and reconciliation in South Africa: Attributions of blame and the struggle over apartheid. The American Political Science Review, 93, 501–517.

He, Z. (2000). Corruption and anti-corruption in reform China. Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 33, 243–270.

Heston, A., Sumners, R., & Aten, B. (2006). Penn world table version 6.2. Center for International Comparisons of Production, Income and Prices at the University of Pennsylvania.

Hetherington, M. J. (1998). The political relevance of political trust. The American Political Science Review, 92, 791–808.

Hu, R. (2005). Economic development and the implementation of village elections in rural China. Journal of Contemporary China, 14, 427–444.

Huntington, S. (1968). Political order in changing societies. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Huntington, S., & Dominguez, J. L. (1975). Political development. In N. W. Polsby & F. I. Greenstein (Eds.), Handbook of political science (pp. 1–114). Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Kam, C., Wilking, J., & Zechmeister, E. (2007). Beyond the “narrow data base”: Another convenience sample for experimental research. Political Behavior, 29, 415–440.

Kennedy, J. J. (2002). The face of “grassroots democracy” in rural China: Real versus cosmetic changes. Asian Survey, 42, 456–482.

Khan, A. R., & Carl, R. (1998). Income and inequality in China: Composition, distribution and growth of household income, 1988 to 1995. The China Quarterly, 154, 221–253.

Khan, A. R., & Carl, R. (2005). China’s household income and its distribution, 1995 and 2002. The China Quarterly, 182, 356–384.

Kinder, D. R., & Kiewiet, R. (1981). Sociotropic politics: The American case. British Journal of Political Science, 11, 129–161.

Kinder, D. R., & Palfrey, T. R. (1993). On behalf of an experimental political science. In D. R. Kinder & T. R. Palfrey (Eds.), Experimental foundations of political science (pp. 1–39). Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Levi, M. (1998). A state of trust. In M. Levi & V. Braithewaite (Eds.), Trust and governance. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Levi, M., & Stoker, L. (2000). Political trust and trustworthiness. Annual Review of Political Science, 3, 475–507.

Levitsky, S., & Way, L. (2002). The rise of competitive authoritarianism. Journal of Democracy, 13, 51–65.

Lieberthal, K. (1995). Governing China. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Lind, E. A., Erickson, B. E., Friedlan, N., & Dickenberger, M. (1978). Reactions to procedural models for adjudicative conflict resolution: A cross-national study. The Journal of Conflict Resolution, 22, 318–341.

Lind, E. A., Kanfer, R., & Earley, P. C. (1990). Voice, control, and procedural justice: Instrumental and non-instrumental concerns in fairness judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 952–959.

Lind, E. A., Lissak, R. L., & Conlon, D. E. (1983). Decision control and process control effects on procedural fairness judgments. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 13, 338–350.

Lind, E. A., & Tyler, T. R. (1988). The social psychology of procedural justice. New York: Plenum.

Linz, J. J. (1975/2000). Totalitarian and authoritarian regimes. Boulder: Lynne Reinner Publishers.

Lober, D. J. (1995). Why protest?: Public behavioral and attitudinal response to siting a waste disposal facility. Policy Studies Journal, 23, 499–518.

Luehrmann, L. M. (2003). Facing citizen complaints in China, 1951–1996. Asian Survey, 43, 845–866.

McCormick, B. L. (1996). China’s Leninist parliament and public sphere: A comparative analysis. In B. L. McCormick & J. Unger (Eds.), China after socialism: In the footsteps of Eastern Europe or East Asia? (pp. 29–53). New York: M.E. Sharpe.

McDermott, R. (2002a). Experimental methodology in political science. Political Analysis, 10, 325–342.

McDermott, R. (2002b). Experimental methods in political science. Annual Review of Political Science, 5, 31–61.

Miller, A. H. (1974). Political issues and trust in government: 1964–1970. The American Political Science Review, 68, 951–972.

Miller, J., & Krosnick, J. (2000). News media impact on the ingredients of presidential evaluations: Politically knowledgeable citizens are guided by a trusted source. American Journal of Political Science, 44, 295–309.

Miller, A. H., & Listhaug, O. (1990). Political parties and confidence in government: A comparison of Norway, Sweden and the United States. British Journal of Political Science, 29, 357–386.

Mishler, W., & Rose, R. (1997). Trust, distrust and skepticism: Popular evaluations of civil and political institutions in post-communist societies. The Journal of Politics, 59, 418–451.

Mishler, W., & Rose, R. (2001a). What are the origins of political trust? Testing institutional and cultural theories in post-communist societies. Comparative Political Studies, 34, 30–62.

Mishler, W., & Rose, R. (2001b). Political support for incomplete democracies: Realist vs. idealist theories and measures. International Political Science Review, 22, 303–320.

Mishler, W., & Rose, R. (2002). Learning and re-learning regime support: The dynamics of post-communist regimes. European Journal of Political Research, 41, 5–36.

Moehler, D. (2009). Critical citizens and submissive subjects: Election losers and winners in Africa. British Journal of Political Science, 39, 345–366.

Mondak, J. J., & Gearing, A. F. (1998). Civic engagement in a post-communist state. Political Psychology, 19, 615–637.

Muller, E. N., & Jukam, T. O. (1977). On the meaning of political support. The American Political Science Review, 71, 1561–1595.

Norris, P. (2002). Ballots not bullets: Testing consociational theories of ethnic conflict, electoral systems, and democratization. In A. Reynolds (Ed.), The architecture of democracy: Constitutional design, conflict management and democracy (pp. 206–247). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Norris, P. (2004). Electoral engineering: Voting rules and political behavior. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

O’Brien, K. J., & Li, L. (2006). Rightful resistance in rural China. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Pastor, R. A. (1999). The role of electoral administration for democratic transitions: Implications for policy and research. Democratization, 6, 1–27.

Pastor, R. A., & Tan, Q. (2000). The meaning of China’s village elections. The China Quarterly, 162, 490–512.

Pei, M. (1995). “Creeping democratization” in China. Journal of Democracy, 6, 65–79.

Przeworski, A., & Limongi, F. (1993). Political regimes and economic growth. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 7, 51–69.

Schedler, A. (2002a). The menu of manipulation. Journal of Democracy, 13, 36–50.

Schedler, A. (2002b). The nested game of democratization by elections. International Political Science Review, 23, 103–122.

Schildkraut, D. J. (2005). The rise and fall of political engagement among Latinos: The role of identity and perceptions of discrimination. Political Behavior, 27, 285–312.

Sears, D. O. (1986). College sophomores in the laboratory: Influences of a narrow database on social psychology’s view of human nature. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 515–530.

Shi, T. (1999). Voting and nonvoting in China: Voting behavior in plebiscitary and limited-choice elections. The Journal of Politics, 61, 1115–1139.

Sigelman, L., Sigelman, C. K., & Walkosz, B. J. (1992). The public and the paradox of leadership: An experimental analysis. American Journal of Political Science, 36, 366–385.

Skitka, L. J., Winquist, J., & Hutchinson, S. (2003). Are outcome fairness and outcome favorability distinguishable psychological constructs? A meta-analytic review. Social Justice Research, 16, 309–341.

Tang, W. (2005). Public opinion and political change in China. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Thibaut, J., & Walker, L. (1975). Procedural justice: A psychological analysis. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Tyler, T. R. (1989). The psychology of procedural justice: A test of the group-value model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 830–838.

Tyler, T. R. (1990). Why people obey the law. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Tyler, T. R., & Rasinski, K. (1991). Procedural justice, institutional legitimacy and the acceptance of unpopular U.S. supreme court decisions: A reply to Gibson. Law & Society Review, 25, 621–630.

UNDP. (2005). UN Human Development Report 2005 international cooperation at a crossroads: Aid, trade and security in an unequal world. New York: UNDP.

Verba, S., Burns, N., & Schlozman, K. L. (1997). Knowing and caring about politics: Gender and political engagement. The Journal of Politics, 59, 1051–1072.

Verba, S., Schlozman, K. L., & Henry, B. (1995). Voice and equality: Civic voluntarism in American politics. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Weatherford, M. S. (1984). Economic ‘stagflation’ and public support for the political system. British Journal of Political Science, 14, 187–205.

Weatherford, M. S. (1987). How does government performance influence political support? Political Behavior, 9, 5–28.

Weatherford, M. S. (1992). Measuring political legitimacy. American Political Science Review, 86, 149–166.

Wessels, B., & Schmitt, H. (2008). Meaningful choices, political supply, and institutional effectiveness. Electoral Studies, 27, 19–30.

Whyte, M. K. (2010). Myth of the social volcano: Perceptions of inequality and distributive justice in contemporary China. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Zhao, D. (2002). An angle on nationalism in China today: Attitudes among Beijing students after Belgrade 1999. The China Quarterly, 172, 885–905.

Zheng, Y. (1994). Development and democracy: Are they compatible in China? Political Science Quarterly, 109, 235–259.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Robert Huckfeldt, Robert Jackman, Cindy Kam, Andrew Mertha, Ethan Scheiner, Tianjian Shi, Hiroki Takeuchi, Jessica Teets, Eddy U, Elizabeth Zechmeister, Guang Zhang, and the Micro Processes Group at UC Davis for valuable feedback on this project. Also, thanks to Yannan Gao, Aofei Lu, Chuanqi Liu, Hua Wang, Yongxiang Wang, Sone Wei, Jingjing Yang, and Hui Zhao for research assistance.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Wilking, J.R. The Portability of Electoral Procedural Fairness: Evidence from Experimental Studies in China and the United States. Polit Behav 33, 139–159 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-010-9119-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-010-9119-8