Abstract

This paper describes superlative constructions in contemporary Syrian (Levantine) Arabic. These have the revealing property that the superlative morpheme may be linearly separated from the term that provides the degree scale it makes reference to. This displacement is syntactically constrained, lending support to theories that postulated movement in the derivation of superlative constructions. The data reported here also document a tight correlation of scopal options for the superlative in Arabic and English, indicating that the languages are uniform at LF, while the surface distribution of the superlative morpheme is wider in Arabic than in English. The remarkable convergence of a variety of interpretational nuances between these two unrelated languages suggests that these uniformities can be traced to Universal Grammar.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

This article investigates the structure and meaning of superlative expressions in contemporary Syrian Arabic and their significance for a general theory of superlatives. The unusual syntactic format of superlatives in Syrian Arabic, henceforth ‘Arabic’, has not been previously described. This article makes an empirical contribution to both the documentation of a little-studied language and to the body of data relevant to a theory of degree constructions in natural language. Superlative constructions in Arabic show the same variety of possible interpretations as has been reported for English. They differ from their English counterparts in that Arabic allows the superlative morpheme (aktar) to be separated in the surface structure from the term that provides the degree argument it binds. On account of this property, Arabic optionally shows some surface word orders that have been claimed to be derived by covert syntactic transformations in English (Szabolcsi 1986; Heim 1995, 2001). The systematic comparison of Arabic and English undertaken here reveals that surface displacement in Arabic is sensitive to configurational constraints that rule out corresponding logical forms in English, lending support to the transformational approach to the derivation of the logical form of superlative constructions. It also finds that surface displacement of aktar may not cross over an NP boundary, yet covert displacement may.

The picture that emerges is one in which English and Arabic share the same conditions on covert displacement of the superlative morpheme, while in both languages surface displacement is more restricted than covert displacement; it is bounded by NP in Arabic and altogether impossible in English. This article begins with a summary of the transformational approach to the interpretation of superlatives and a non-transformational alternative. Subsequent sections present a description of the superlative construction in Arabic and evidence that movement is involved in the displacement of the superlative.

2 Syntax and semantics of the superlative construction

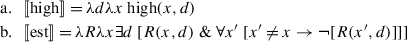

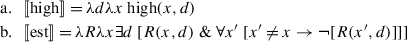

Contemporary analyses of scalar predicates attribute a degree argument to them, so that an adjective like high denotes a relation between an individual and a degree (1a) (Cresswell 1976). Degree scales are downward monotonic; if an entity is high to a degree, it is high to all lesser degrees. Drawing on Seuren (1973), Heim (1995) attributes a denotation to the English superlative morpheme est that combines with a degree relation and an individual and asserts that the individual bears the degree relation to a degree that no other individual bears the degree relation to (1b). Throughout this article, I refer to the scalar term that contributes the degree argument to the relation that the superlative morpheme combines with as the ‘scalar associate’ of the superlative morpheme.

-

(1)

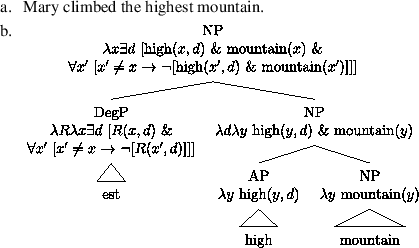

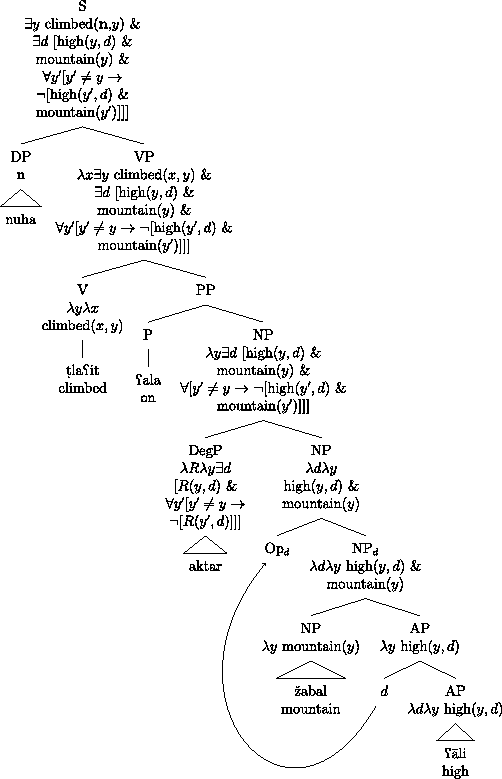

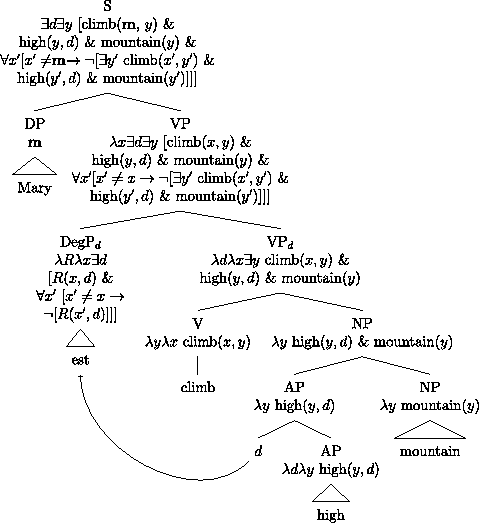

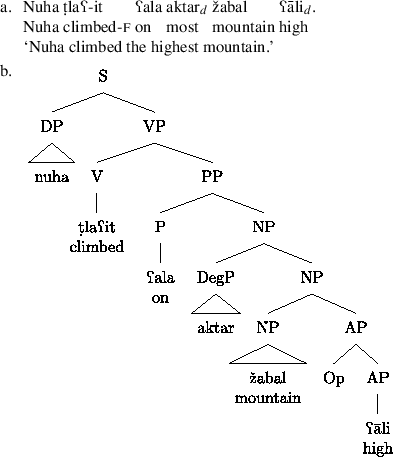

Contemporary analyses of the superlative agree that one reading of a sentence like (2a) compares the mountain that Mary climbed not with high things in general but specifically with other high mountains, and therefore that the semantic composition of (2a) on this reading contains the NP diagrammed in (2b), where high mountain functions as the degree relation argument of est. The superlative est combines with a degree relation abstracted over the degree argument of the scalar associate high. Analyses differ in their take on how the degree relation is derived, more on which below. On the assumption that the is interpreted in the conventional way in (2a), it contributes the presupposition that a unique entity exists that meets the description in (2b). This entity serves as the internal argument of climb. Example (2a) then asserts that Mary climbed the unique mountain which is higher than all other mountains. I attribute to est the syntactic category DegP (Degree Phrase). This semantic derivation derives what is called the ‘absolute’ reading of the superlative in (2a), where it compares members of the NP denotation in terms of the scalar associate of est (height in this example).

-

(2)

I add here that although the absolute reading of (2a) asserts that there is no mountain that is as high or higher than the one Mary climbed, this assertion does not project through negation, and therefore is not a presupposition of (2a). This means that the definite article in fact does not have its standard meaning in absolute superlatives. The example in (3a) is true if there are two mountains in Kenya that have the exact same height, and Mary climbed one of them (the modifier in Kenya favors the absolute reading over the ‘relative’ reading described below). This means that the phrase the highest mountain in Kenya does not presuppose the existence of a unique referent, in contrast to a garden variety definite like the 3000m mountain in (3b), which induces a presupposition failure if two mountains meet the description. Further, Coppock and Beaver (2015) point out that superlatives have a predicative use that fails to presuppose existence, as demonstrated by the fact that (3c) is true even if there is no largest prime number. I conclude from these facts that the definite article is in fact interpreted as an indefinite article in absolute superlatives. While this conclusion raises further questions, it is supported by the fact that in Arabic, superlative phrases are morphologically indefinite on both the absolute reading and the relative reading described below; I present the relevant Arabic data in Sect. 3.

-

(3)

-

a.

Mary didn’t climb the highest mountain in Kenya; there’s another one there that’s exactly as high.

-

b.

-

*

Mary didn’t climb the 3000m mountain; there’s another one that’s exactly as high.

-

*

-

c.

Seven is not the largest prime number.

-

a.

In addition to the absolute reading of the superlative, a ‘comparative’, or ‘relative’, reading is typically also available (Ross 1964; see von Stechow 1984; Heim 1985 and Rullmann 1995 on similar ambiguities in the comparative). The relative reading of (2a) asserts that Mary climbed a higher mountain than anyone else climbed. Here we compare Mary with alternatives in terms of how high a mountain they climbed, and Mary need not have climbed the highest mountain in the world.

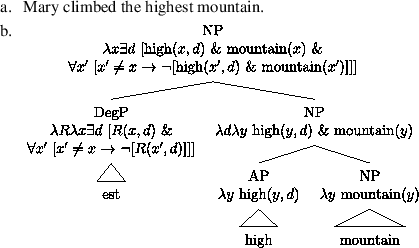

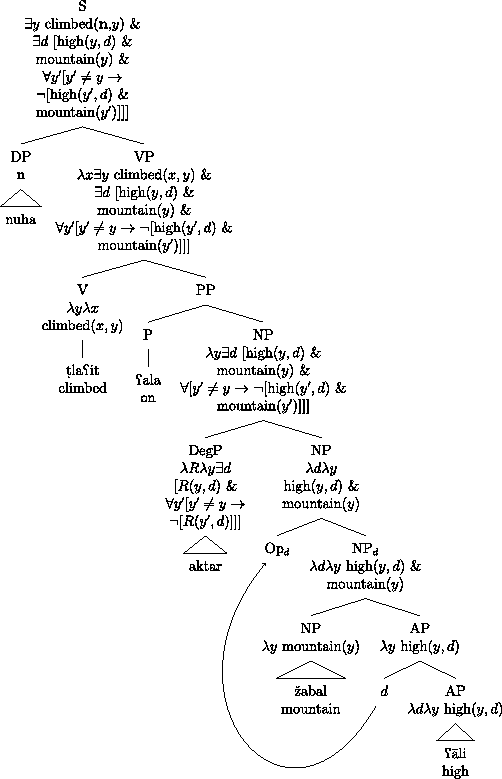

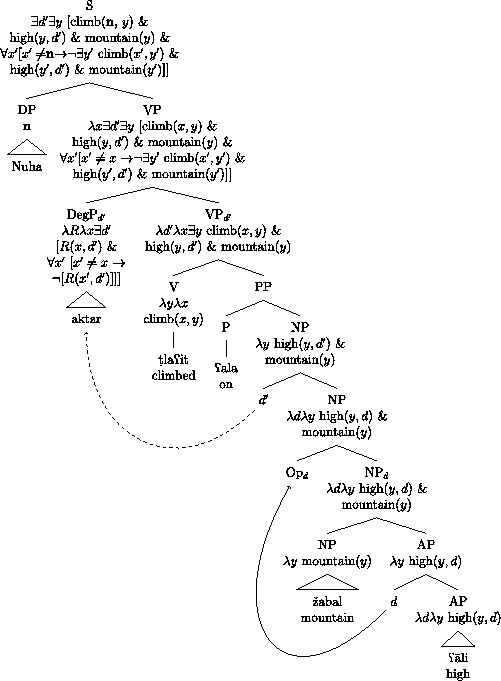

Contemporary analyses of the superlative differ in their approach to relative readings. Szabolcsi (1986), Heim (1995) and others claim that the relative reading differs from the absolute reading in the structural scope of the superlative morpheme in the sentence’s logical form (LF), a structured representation of the sentence’s meaning, derived on the movement account by the same processes that relate a syntactic base structure to a surface structure, or ‘phonological form’ (PF) (May 1977, 1985). According to this approach, the superlative morpheme est is concatenated with its scalar associate in the base structure (the adjective high in (2a)), but instead of being displaced to the NP edge as in (2b), it is displaced further to the VP edge, as illustrated in (4). I assume the syntactic index of est is copied to its sister constituent, deriving the category symbol VPin this case, and that VPis interpreted as a lambda-abstract over the d variable in VP, as shown in (4).

-

(4)

Szabolcsi and Heim point out that this derivation only generates the correct interpretation if the definite article that occurs in the surface structure is interpreted as an indefinite article in the LF. If the occurred in the tree in (4) with its standard interpretation, it would bring with it the presupposition that there exists a unique d-high mountain, and therefore that no equally high or higher mountain exists (because of the monotonicity of height). This is just the assertion that the movement analysis seeks to avoid by moving est. Therefore, the movement analysis of the relative reading of (2a) can only be correct if the fails to contribute definiteness on that reading. Szabolcsi and Heim both analyze absolute superlatives as definite, turning the fact that relative superlatives are indefinite into a puzzling contrast. However, the data in (3) suggest that even absolute superlatives are indefinite, and therefore that relative superlatives are no different from absolute superlatives in this respect. It remains puzzling why the definite article occurs in English superlatives, though as we will see, superlatives in Arabic are morphologically indefinite.Footnote 1 I propose that on both the absolute and relative readings of (2a), the object is interpreted as a bare predicate that modifies the internal argument of the verb climb (see Kratzer 1996 and Chung and Ladusaw 2004 on the mechanics of this step). The resulting unsaturated VP is closed by default insertion of an existential quantifier (Heim 1983; Kamp 1984; Diesing 1992), yielding the bottommost VP denotation in (4) in the relative construction.

The denotation of the tree in (4) asserts that there is a degree d such that Mary (m in (4)) climbed a mountain with height d and no one else climbed a mountain with height d. This assertion is compatible with the existence of mountains higher than the one Mary climbed, as long as no one climbed them. The relative reading of sentences like (2a) typically implies a set of specific alternative individuals we are comparing Mary to. As a result, (2a) is judged true even if someone did climb a mountain higher than the one Mary climbed, as long as that person is not a relevant alternative to Mary. If we are talking about who won this year’s mountain climbing contest, for example, the results of last year’s contest are not relevant. Consequently, it would be appropriate to include a domain restriction on the universal quantifier in the definition of est in (1b) that limits its range to the set of individuals relevant to the comparison with Mary—her ‘alternatives’. However, in the service of improving the legibility of the formulas presented here, I omit this domain restriction, and instead stipulate that the universal quantifier is always understood to have a domain that is restricted to a set of individuals made salient by the context.

Heim (1995) entertains the possibility of exploiting this contextually specified domain restriction to capture the relative reading without movement of est. But she claims there is no way of manipulating the domain restriction to derive what Sharvit and Stateva (2002) call the “upstairs de dicto” reading of examples like (5). On the upstairs de dicto reading of (5), the object of Mary’s desire is a certain height, but no particular mountain. Mary may want to climb a mountain that is at least 5000m high (to acquire a certification, for example), without having a particular mountain in mind and without having any attitude toward the other climbers’ desires. If Bill wants to climb a 4000m mountain and John a 3000m mountain, then Mary wants to climb the highest mountain in this sense. Here, there are no ‘relevant’ mountains we could restrict ourselves to to make (5) true in this situation.

-

(5)

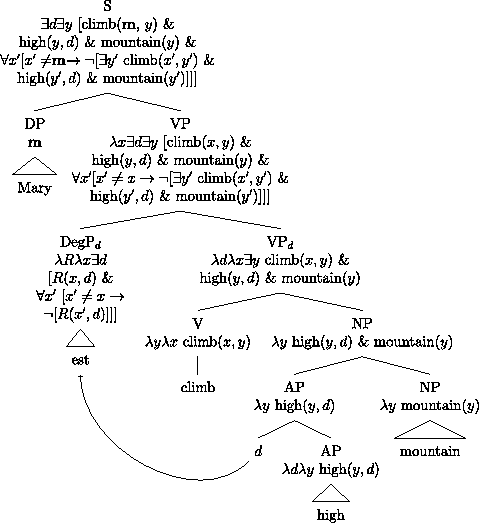

Mary wants to climb the highest mountain.

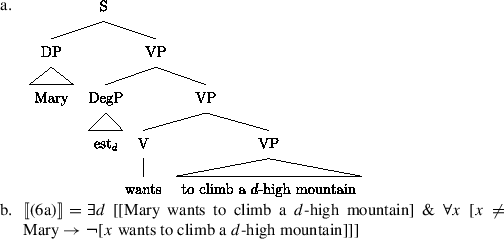

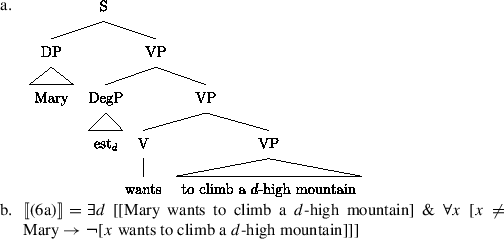

But Heim points out that covert movement of est to a scope position external to the intensional verb want, leaving its host adjective in situ (6a), derives the relevant reading, spelled out in (6b), once again on the assumption that the definite article is interpreted as an existential quantifier. In the service of conserving space I omit the derivational details here, which are the same as in (4) except for the higher landing site of est. (6b) says that there is a degree d such that Mary wants to climb a mountain that is d-high, and no one else wants to climb a mountain that is d-high, which captures the upstairs de dicto reading of (5).

-

(6)

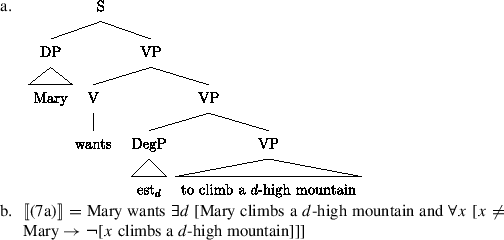

On the movement approach, an additional relative reading of (5) is derived by movement of the superlative operator to a position subordinate to the modal verb want, as illustrated in (7a). This is also a relative reading, where we compare Mary to other mountain climbers in terms of how high a mountain they climb in Mary’s desire-worlds. The composition of this tree, sketched in (7b) asserts that what Mary wants is to climb a higher mountain than anyone else climbs, i.e., she wants to beat the others at mountain climbing. These two readings exist independently of an absolute reading where Mary wants to climb the actual highest mountain in the world.

-

(7)

On the movement analysis, the scope of the negative operator ‘¬’ in the predicate logical reductions here and to follow corresponds systematically to the LF position of the superlative morpheme in the corresponding syntactic structure. For example, want occurs in the scope of est in the tree in (6a) and in the scope of negation in the reduction in (6b), but not in (7a) and (7b). The approximate syntactic logical form that the movement analysis posits can therefore be read off the predicate logical representations of the corresponding readings in these examples and those to follow.

In contrast to Szabolcsi’s and Heim’s movement approach, Gawron (1995), Farkas and Kiss (2000), Sharvit and Stateva (2002), Gutiérrez-Rexach (2006), Teodorescu (2009) and Krasikova (2012) claim that the readings of the superlative construction can be derived without movement of the superlative morpheme beyond the DP containing it in the surface structure. Sharvit and Stateva (2002) treat the upstairs de dicto reading in detail that Heim claims is problematic for a non-movement account. They propose that the relevant reading is derived through the introduction of a covert operator at the NP level and type-shifting of the meaning of the definite determiner. A summary that does full justice to Sharvit and Stateva’s account would go beyond the space available here; the following remarks are intended as a sketch of their system for the upstairs de dicto reading of a sentence like (8a). The general idea is to restrict ourselves to possible worlds in which everyone climbs the lowest mountain that fulfills their needs, and there are no other mountains. Then, having the greatest ‘need’ is tantamount to climbing the highest mountain in each of these worlds. Specifically, Sharvit and Stateva derive the upstairs de dicto reading of (8a) from the LF in (8b), where the covert operator IDENT′-W* combines with the NP and est remains NP-internal. The numerals are abstraction indices.

-

(8)

-

a.

Mary needs to climb the highest mountain.

-

b.

Mary needs [1 [PRO to climb-w1 [the-\(\mathscr{J}\) [IDENT′-W* [2 [est [high mountain-w2]]]]]-w1]]

-

a.

IDENT′-W* is an operator that combines with a property P and derives the set of properties that have the same extension as P in every world in the contextually supplied set of worlds W*. In the case at hand, W* is the set of worlds that minimally satisfy everyone’s needs. If Mary needs to climb a 5000m mountain, Bill a 4000m mountain and John a 3000m mountain, then W* contains all the worlds in which Mary climbs a mountain that is exactly 5000m high, Bill climbs one that is exactly 4000m high, and John climbs one that is exactly 3000m high, and there are no other mountains. This is a set of worlds in which be the highest mountain and be a 5000m high mountain have the same value. The constituent [IDENT′-W* [est [high mountain]]] in (8b) then denotes the set of properties extensionally equivalent to the property of being the highest mountain in every world in W*, in this case, the set containing the property be a 5000m mountain. Sharvit and Stateva then propose that the definite article is type-lifted from its usual denotation, which maps sets of individuals to individuals, to a denotation that maps sets of properties to properties. The article occurs with a contextual domain restriction \(\mathscr{J}\) that in the lifted derivative denotes a set of properties made salient by the context. The article denotes a function that maps a property of properties \(\mathscr{P}\) to the unique property that is in both \(\mathscr{P}\) and \(\mathscr{J}\). In the case at hand, the context makes the value {be a 5000m mountain, be a 4000m mountain, be a 3000m mountain} salient for \(\mathscr{J}\). The superlative DP in (8b) then denotes “the unique property P which is a member of \(\mathscr{J}\) and which in each world in W* has the same value as the property of being the highest mountain” (p. 480). Example (8a) then asserts that Mary needs to climb a mountain that has this property P, which in this context is the same as saying she needs to climb a 5000m mountain. In this manner, Sharvit and Stateva derive the upstairs de dicto reading of (8a) without moving est out of the NP it is base generated in.

One expectation that arises under the movement analysis of the superlative is that there might be languages in which the superlative morpheme (counterpart of est) moves overtly. In this article, I present a description of superlative constructions in Syrian Arabic, where the superlative morpheme may in fact be separated from its scalar associate in the surface structure. This displacement is subject to constraints that mirror constraints on the availability of relative interpretations of the superlative in English. While these observations do not contradict the in situ analysis of English as such, the parallels reported here suggest that relative readings in English are derived by the same operation that is responsible for overt displacement in Arabic. The operation applies at a different level of representation in the two languages but is subject to similar grammatical conditions. The parallels therefore lend support to the movement analysis.

Throughout this article, I refer to superlative phrases of the type described above, whether absolute or relative, as ‘argument’ superlatives, because they occur in argument positions. I distinguish these from ‘adverbial’ superlatives such as the fastest in (9a), where the superlative associates with a gradable adverb. A lexically gradable term like the adjective high above or fast in (9a) functions as the scalar associate in what is called the ‘superlative of quality’. The plurality of a noun may also function as the scalar associate of the superlative morpheme in what Gawron (1995) calls the ‘superlative of quantity’, illustrated in (9b). These are formed in English by adnominal the most but in Arabic by the adverbial superlative, as described in Sect. 4. Adverbial the most may also function as a superlative of quantity modifying the pluractionality of the verb phrase itself. On one reading of (9c), for example, it compares the number of times Mary climbed Mount Everest with the number of times alternatives to Mary climbed Mount Everest.

-

(9)

-

a.

Mary climbed Mount Everest the fastest.

-

b.

Mary climbed the most mountains.

-

c.

Mary climbed Mount Everest the most.

-

a.

The Arabic facts reported here have been elicited from three native speakers from Mharde, in central Syria (population approx. 20000). Fragments of this data have been confirmed by speakers from outside Mharde as well as speakers from Lebanon, Palestine and Jordan, so the displacement phenomenon described here appears to be typical of at least the Levant region. The pronunciation reflected in the transcriptions below is characteristic of the Mharde variety and differs from that found in urban centers. The transcription is broad and reflects attributes of the Mharde variety that I take to be phonemic, including the feminine ending [i] that is pronounced [e] in urban dialects of the Levant and the uvular stop [q] which has weakened to [ʔ] in urban dialects. The transcription also reflects phonological effects of the inflectional context on verb stems, generally vowel syncope, as well as assimilation of the definite article /l/ to a following coronal consonant. The transcriptions do not include variation in vowel quality that is phonologically determined or in free variation. What I transcribe as a, for example, varies between [e], [Ɛ] [ə] and [a], and is rounded to [o] in word final closed syllables, which is not reflected in the transcriptions here. See Yoseph (2012) for a description of the phonology of the Arabic spoken in Mharde. My glosses for the Arabic examples comply with Noyer’s (1992) morphological analysis of Arabic according to which third person, masculine and singular are not marked, and the yi- prefix seen in some imperfective verb forms is a default placeholder for an unfilled inflectional prefix position, glossed “∅”. I gloss the prefix b- that occurs in finite imperfective forms as a present tense morpheme, but see Aoun et al. (2010) for a more detailed discussion. Feminine is glossed f and plural p.

Sections 3 and 4 describe argument and adverbial superlatives in Arabic, Sect. 5 describes evidence that displacement of the superlative in Arabic involves movement, including a variety of bounding conditions, and Sect. 6 presents a syntactic analysis of the phenomenon.

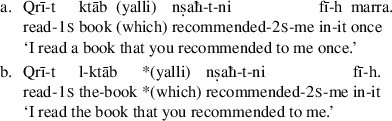

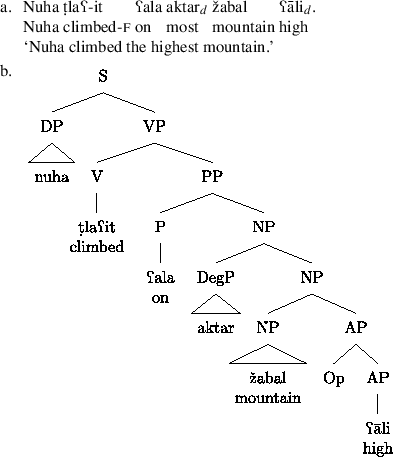

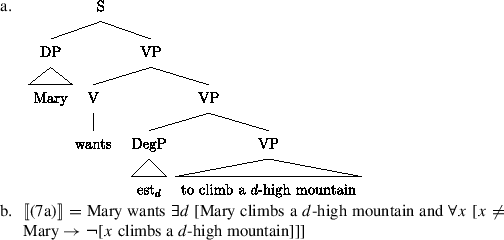

3 Argument superlatives

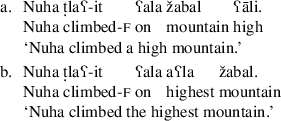

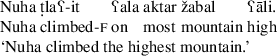

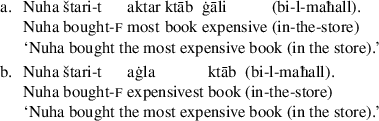

In Arabic, positive adjectives follow the noun they modify (10a). Superlative adjectives, however, precede the head noun (10b). The superlative morphological form of an adjective is built by substituting the three root consonants of the adjective into the prosodic template aC1C2aC3. Positive ħasan (good) has the superlative form aħsan (best), raxīṣ (cheap) has the superlative arxaṣ (cheapest), etc. Regular phonology sometimes produces deviations from this general pattern. The adjective ʕāli (high) has the superlative form aʕla (highest), where a final y (/j/) has been deleted from both forms.

-

(10)

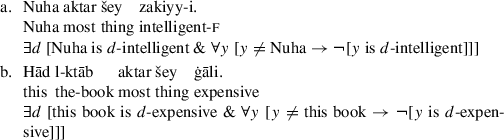

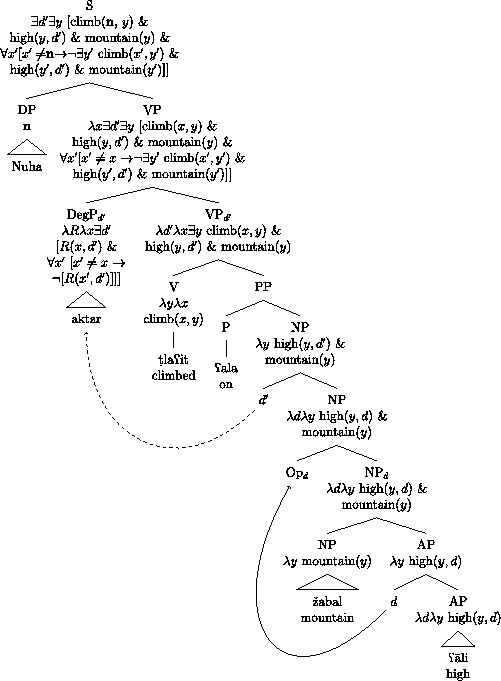

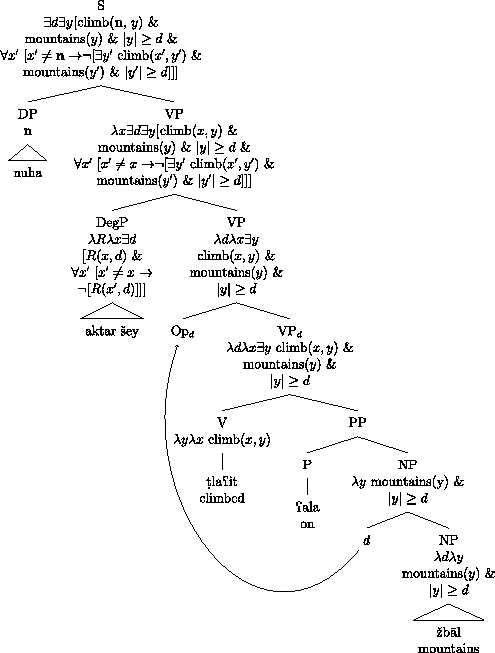

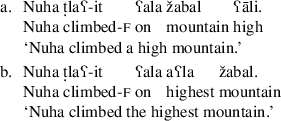

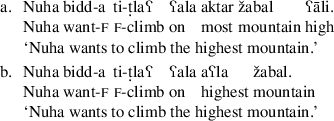

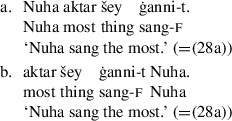

In addition to the format in (10b), argument superlatives may have the format shown in (11), where the term aktar is appended to a noun phrase containing a positive adjective in its usual post-nominal position (cf. (10a)). The term aktar adds to the meaning of žabal ʕāli (high mountain) what English -est adds to high mountain in the English counterpart (2a), indicating that aktar is the Arabic equivalent of -est. The term aktar is itself the superlative form of the adjective ktīr (much/many). It therefore has the same morphological composition as that attributed to most (namely much/many+est) by Bresnan (1973), Hackl (2009) and others.Footnote 2

-

(11)

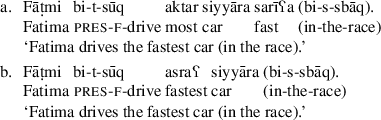

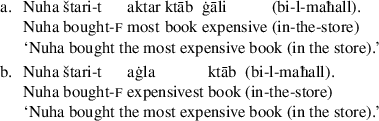

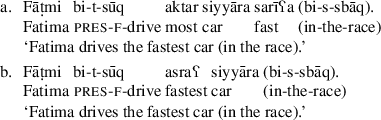

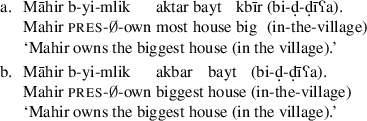

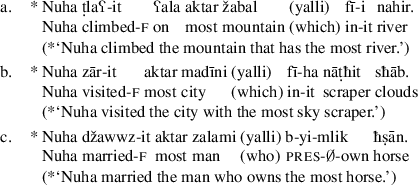

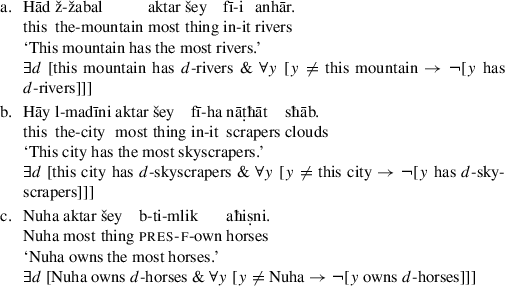

A few additional examples follow. In each case, the a- and b-examples are synonymous. The parenthesized material favors the absolute reading, as in the English translations (Farkas and Kiss 2000).

-

(12)

-

(13)

-

(14)

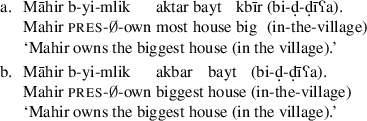

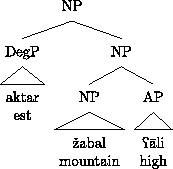

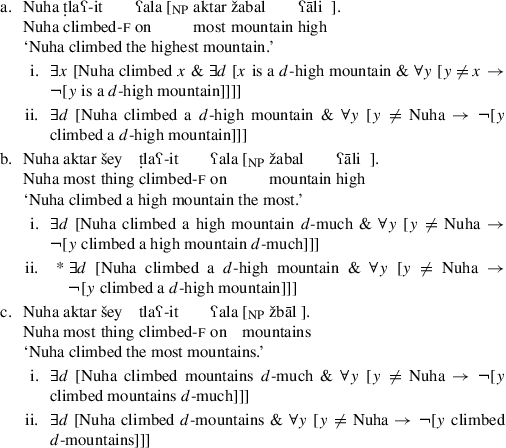

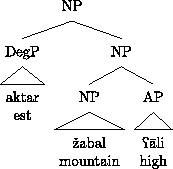

The a-examples above mirror the word order posited for the logical form of the English (absolute) superlative diagrammed in (2b), where the superlative morpheme precedes a noun phrase containing an adjective in its canonical position vis a vis the head noun. This similarity implicates an analogous structure for Arabic, diagrammed schematically in (15). No definite article is found in either the a- or b-examples above. If a DP layer is present in these cases, it goes unpronounced, and I do not include it in the trees below. Since the canonical placement of the adjective is post-nominal in Arabic, the pre-nominal placement seen in the b-examples above appears to be derived by fronting the adjective to, or together with, the superlative morpheme aktar.

-

(15)

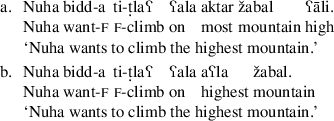

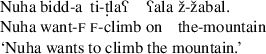

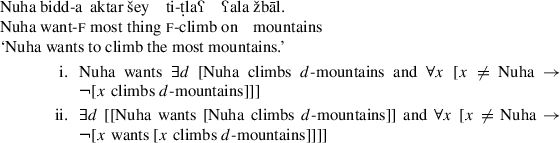

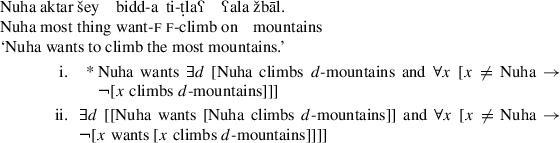

Like English, Arabic argument superlatives display both an absolute and a relative reading, regardless of whether aktar occurs alone at the NP edge or together with the associated adjective. Both construction types also display an upstairs de dicto reading in the context of an intensional operator. The examples in (16) have the same range of meanings as the English counterpart in (5), including the upstairs de dicto reading that asserts that there is a particular height such that Nuha wants to climb a mountain that high, and no one else wants to climb a mountain that high.

-

(16)

As mentioned above, the superlative NPs in the examples above and to follow, whether formed with aktar or the superlative adjective itself, do not bear the Arabic definite article l- seen in a definite, non-superlative phrase like the object in (17) (where l- assimilates to following ž). This assertion is only felicitous in a context in which ž-žabal (the mountain) has a unique, previously mentioned referent. There is no indefinite article in Arabic; indefiniteness is signified by the absence of the definite article. This means that the superlative NPs discussed above are morphologically indefinite. This fact is in line with the observations in (3) indicating that even absolute superlatives are semantically indefinite in English as well (and these data can be replicated in Arabic). Another reason to believe that Arabic superlatives are indefinite is discussed shortly.Footnote 3

-

(17)

The fact that the displacement posited for the absolute reading is visible in the surface structure in Syrian Arabic raises the question of how well the placement of aktar in general tracks the placement of est in the corresponding English logical forms posited by the movement analysis of relative readings, including the upstairs de dicto reading of examples like (16). That is, do the overt placement options for aktar correspond systematically to scope placement options for English est? If so, the phenomenon lends circumstantial support to the movement analysis of relative readings in English. The remainder of this article addresses this question. For reasons that will become clear, a definitive answer to the question of whether aktar can be displaced over bidda in (16) must await a discussion of the behavior of adverbial superlatives (Sect. 4) and certain constraints on surface displacement in Arabic (Sect. 5). The remainder of this section fleshes out the behavior of argument superlatives.

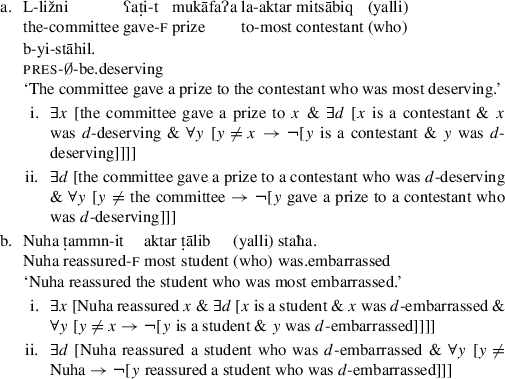

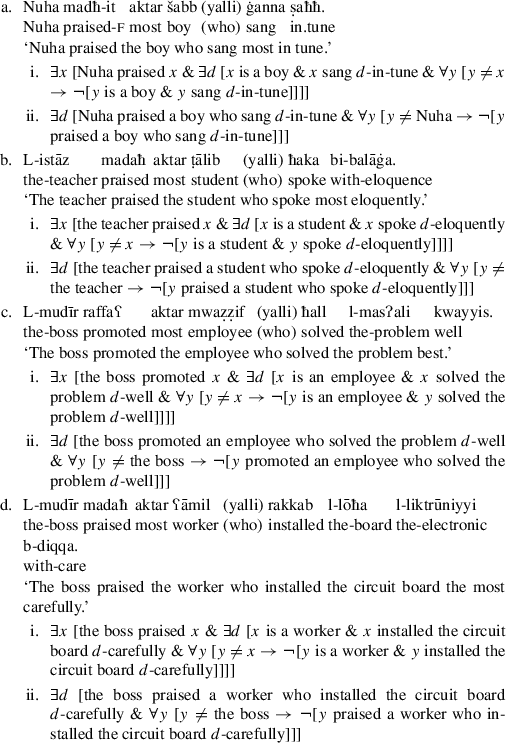

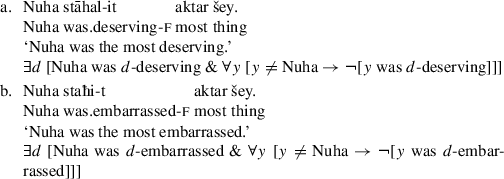

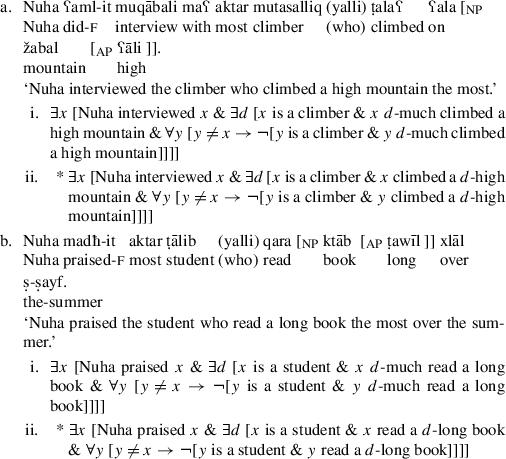

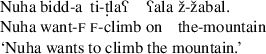

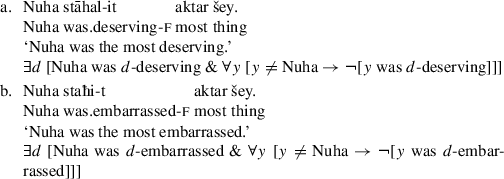

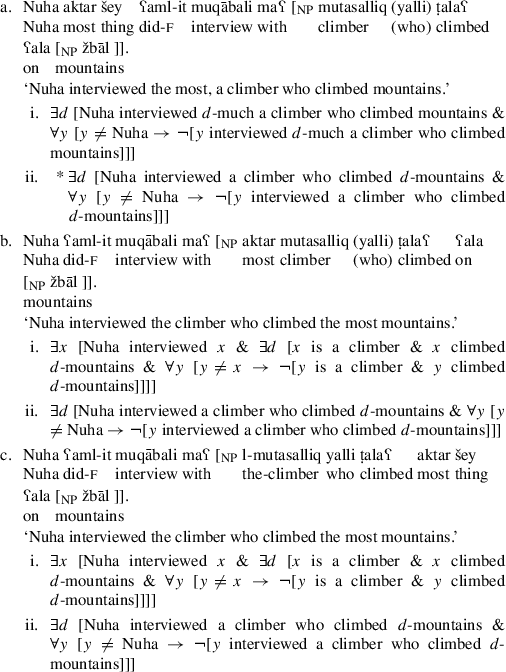

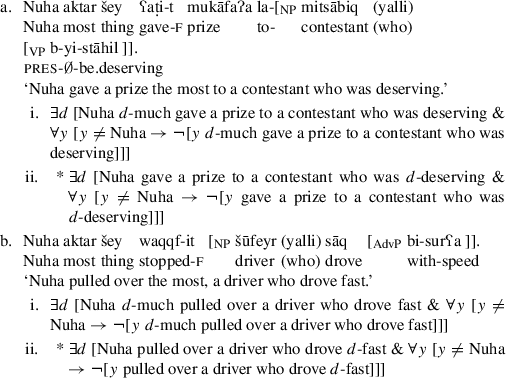

In the format [aktar [NP AP]], AP may be replaced by a relative clause if this relative clause contains a gradable term that may function as the scalar associate of aktar. For example, a degree verb such as stāhal (be deserving) or staħa (be embarrassed) may contribute a scale to the interpretation of aktar in the construction in question, as in the examples below. The predicate logical formulas below represent the readings shared by the Arabic example and its English translation.

-

(18)

The salient reading of (18a) is that the committee gave a prize to a contestant who was more deserving than any other contestant, as the (i)-translation makes explicit. Example (18b) asserts most saliently that Nuha comforted the student who was more embarrassed than any other student. A less salient subject-oriented relative reading is available as well in which we compare the committee in (18a) to other prize-giving bodies, and Nuha in (18b) to other reassurers of embarrassed students, as the (ii)-translations make explicit. In both cases, the degree verb in the relative clause functions as the scalar associate of aktar. On the (i)-readings, aktar is interpreted in the position it occurs in the surface structure, where it compares contestants and students in (18a) and (18b) respectively. According to the movement account of the derivation of relative readings, the (ii)-readings require covert displacement of aktar to a higher position.

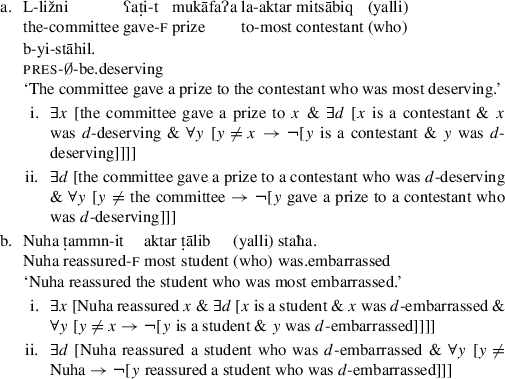

I note here in passing that the superlative may also occur within the relative clause in Arabic, in a structure similar in form to the English translations above. These cases are discussed in detail in Sect. 5. Note too that the fact that the relative pronoun yalli is optional in the superlative examples above and to follow is further evidence that the superlative construction is morphosyntactically indefinite in Arabic. This is because in Syrian Arabic, the relative pronoun yalli is optional whenever the head of the relative clause is indefinite, as illustrated in (19a) below, but obligatory when it is definite, as illustrated in (19b) (see Brustad 2000). If aktar mitsābiq (most contestant) in (18a) were definite, then yalli would be obligatory there, on analogy to (19b). This is the additional evidence for the indefiniteness of Arabic superlatives promised in Sect. 2.

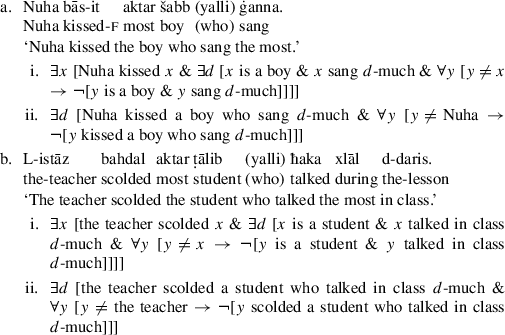

-

(19)

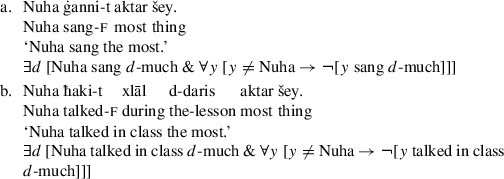

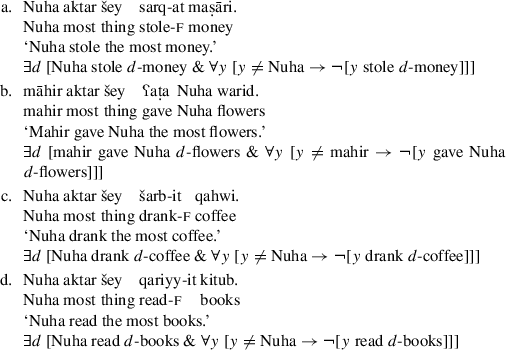

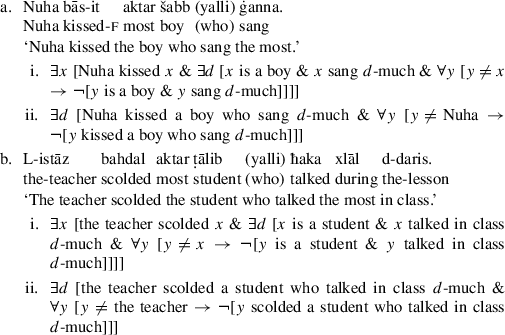

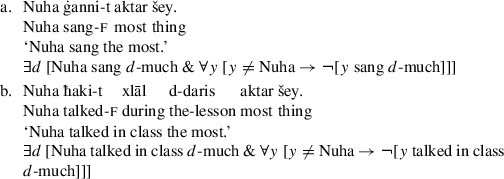

A non-degree verb in the relative clause may license aktar when it is interpreted pluractionally, where the scale it contributes measures either the number or duration of such events, as in (20). Example (20a) may be read to mean that Nuha kissed the boy who sang more than any other boy sang, and example (20b) that the teacher scolded the student who talked in class more than any other student talked in class. These are the readings represented in the (i)-translations. In these examples, ġanna (sing) and ħaka (talk) relate an agent to an amount of singing or talking, and this amount constitutes a scale over which degree abstraction is possible, making a degree relation available to aktar in such cases. Once again, a subject-oriented relative reading is available where we compare Nuha in (20a) to others who kissed boys who sang and assert that the boy she kissed sang more than the boys her alternatives kissed (the (ii)-translations below).

-

(20)

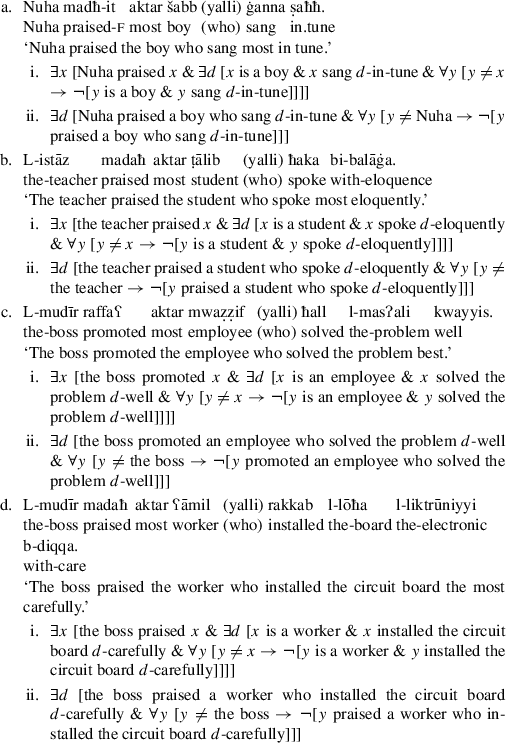

A gradable adverb in the relative clause may license aktar as well, as the examples in (21) show. Since, as we have seen above, the verb phrase within the relative clause carries a degree argument associated with pluractionality, the sentences below are ambiguous depending on whether aktar associates with the gradable adverb or the pluractionality of the verb phrase. In the first case, (21a) asserts that Nuha praised the boy who sang the most in tune (the (i)-translation sketched there). In the second, it asserts that Nuha praised the boy who sang in tune the most, i.e., most often or on the most occasions. Having demonstrated the possibility of a pluractional associate for aktar in (20), I highlight here only the first reading mentioned above, as well as its subject-oriented relative counterpart in the (ii)-translations below, where we compare Nuha with others in terms of how in tune the boy they praised sang.

-

(21)

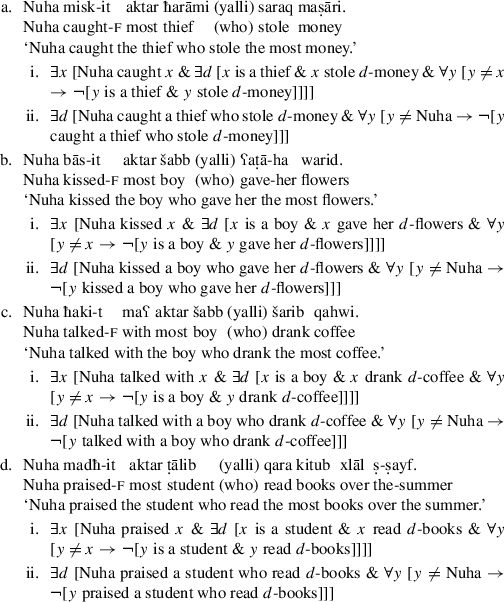

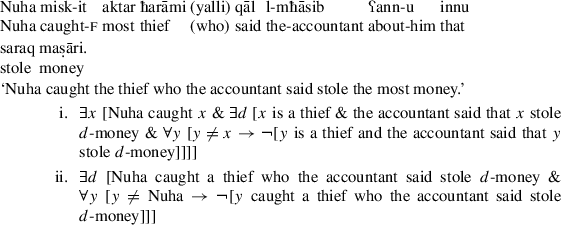

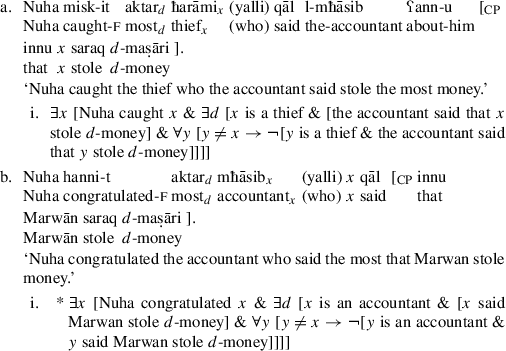

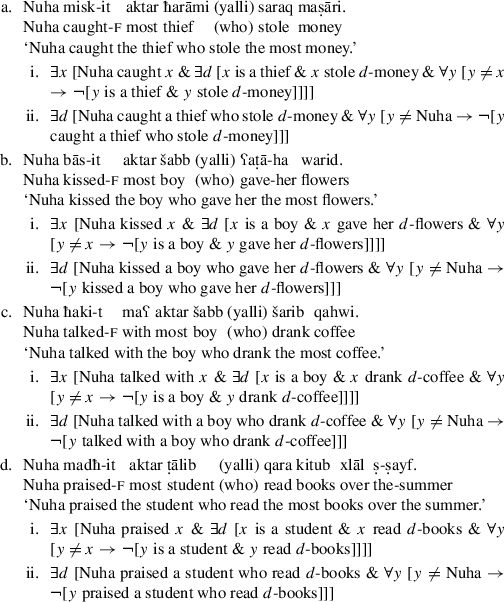

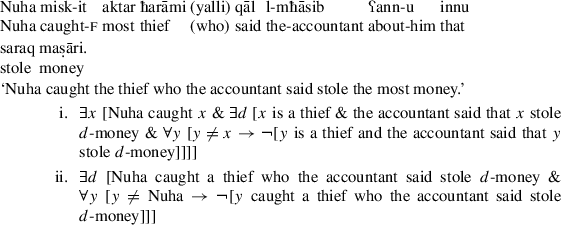

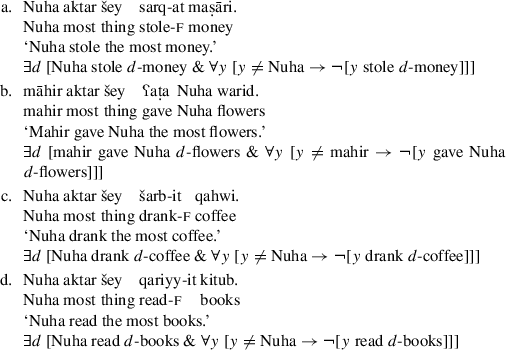

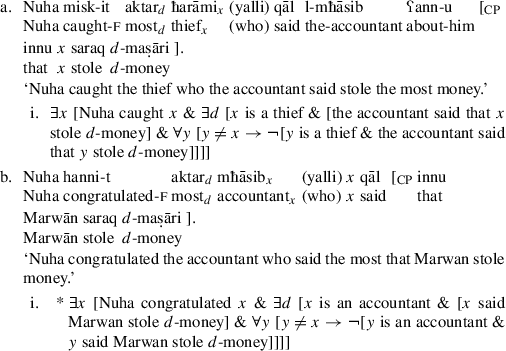

Not only may a degree verb, a scalar adverb or pluractionality license aktar, but so may an indefinite plural or mass noun within the relative clause. For example, (22a) below may assert that Nuha caught the thief who stole more money than any other thief under consideration did (i). This observation indicates that plural and mass nouns take a scalar argument of quantity, as Gawron (1995) proposes, that aktar may associate with. I notate the degree argument as a prefix of the plural or mass noun in the formulas below. That is, ‘d-flowers’ should be read ‘d number of flowers’ and ‘d-coffee’ should be read ‘d amount of coffee’. A subject-oriented relative reading is available that asserts that Nuha caught a thief who stole more money than any thief caught by anyone else (ii). Since these verbs are eventive, pluractionality still represents a possible scalar associate for aktar in these examples, where e.g. (22a) asserts that Nuha’s thief stole money on more occasions than anyone else did. Having discussed this reading in connection with the examples in (20), I ignore it here, except to demonstrate below that the quantity readings in (i) and (ii) are independent of pluractionality.

-

(22)

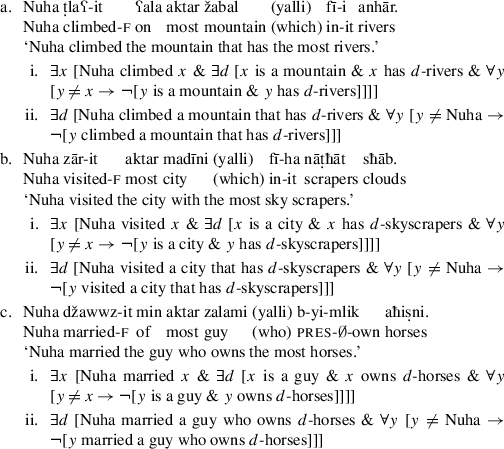

Since a pluractional associate for aktar is available in the examples above, and since someone who, for example, stole money on the most occasions probably has stolen more money than anyone else, the reading where aktar associates with a plural noun phrase is potentially difficult to distinguish from the reading where it associates with pluractionality of the verb. But the difference is easy to detect in context of stative non-degree verbs, as in (23), since no pluractional associate is available there. A mountain can have a lot of rivers, as (23a) asserts, but it cannot ‘have rivers a lot’. The fact that the predicate have rivers licenses aktar means that aktar is able to bind the plural term anhār (rivers) in this context. Also as before, a subject-oriented relative reading is available in these cases.

-

(23)

As expected, replacing the plural with a singular noun phrase renders the sentences above ungrammatical, since aktar then has no scalar associate, as the examples below show. These examples clarify that aktar may associate with a plural or mass noun phrase independently of the possibility of a pluractional reading of the verb phrase.

-

(24)

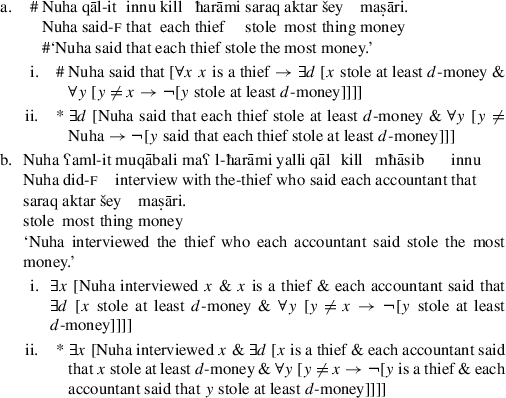

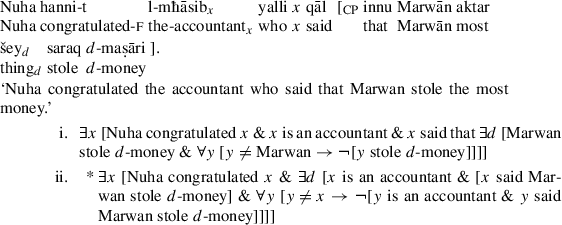

I point out lastly that the dependency between aktar and a scalar associate is not clause-bound, as (25) below shows, where aktar associates with the plural maṣāri (money) across the boundary of the complement clause of qāl (say). This reading is spelled out in (i) and its subject-oriented counterpart in (ii). The pluractionality of the verbs qāl (said) and saraq (stole) are also possible associates of aktar in this example (not spelled out here). All other things being equal, aktar prefers to pick up a more local associate than a more distant one. As a result, the long-distance associate maṣāri is not the most salient associate for aktar out of the blue. But if we know that the accountant said that Mahir stole 300 liras, Ahmed stole 400, and Sami stole 500, and that Nuha caught Sami, (25) sums up this situation naturally.

-

(25)

In summary, adnominal aktar may associate with any scalar term in its c-command domain (subject to bounding conditions discussed in Sect. 5), as schematized in (26), where XP = AP, AdvP, VP, or plural (or mass) NP. The dependency may cross a clause boundary as (25) shows. Note lastly that the English translations to all the examples above display each of the readings attributed to the Arabic there, including, again in the proper context, the long-distance example in (25). In English, the superlative morpheme must occur local to its scalar associate, either affixed to it in the form of est or adjacent to it in the form of most. But English and Arabic are interpretationally uniform.

-

(26)

[NP aktar d [NP …XP d …]]

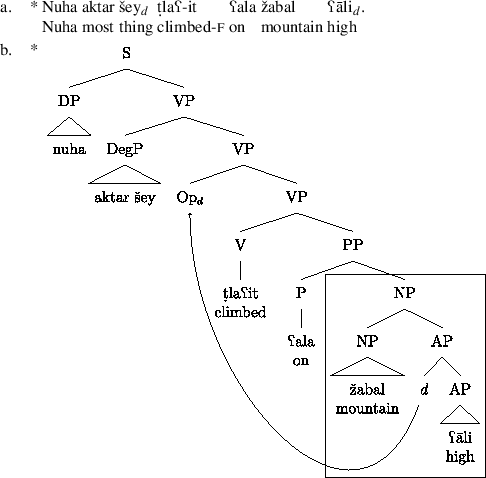

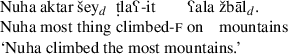

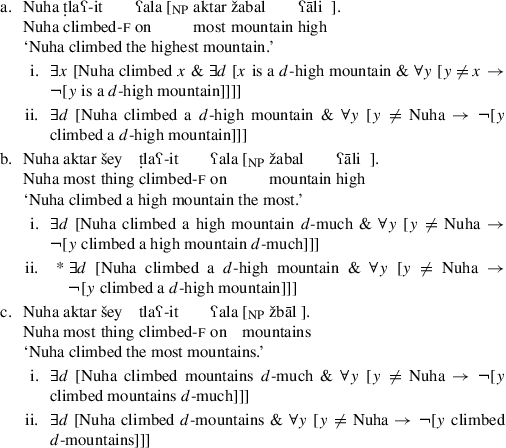

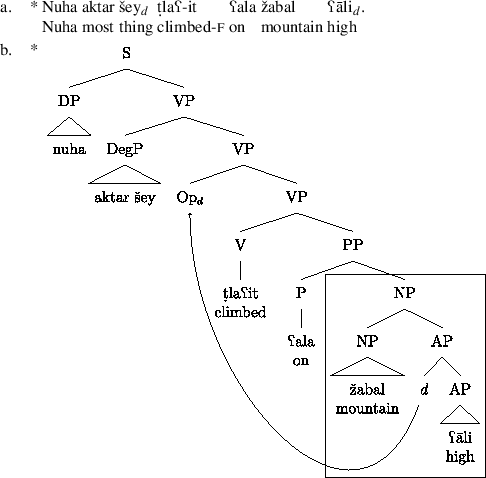

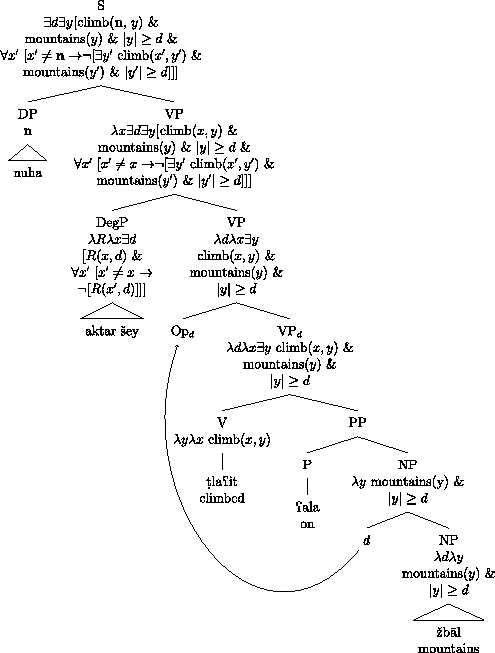

4 Adverbial superlatives

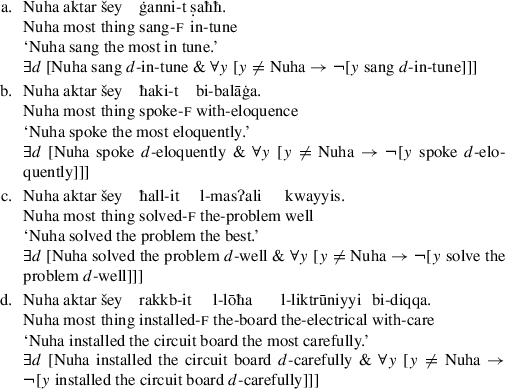

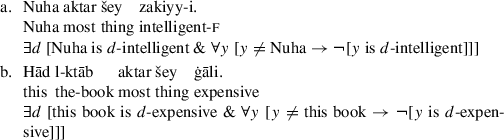

In this section, I describe the behavior of the adverbial counterpart to adnominal aktar, and show that it, too, may be displaced from its scalar associate in the surface structure. As an adverbial modifier, aktar occurs obligatorily in construct with the noun šey, meaning thing. The noun šey does not occur in other adverbs; it appears to be grammaticalized in the phrase aktar šey (literally most thing), illustrated in (27). I show below that aktar šey may be displaced from its scalar associate just like adnominal aktar, and demonstrate later that displacement of aktar and aktar šey are subject to the same bounding conditions. In light of these similarities, I proceed under the assumption that aktar šey is an adverbial allomorph of adnominal aktar, though the role and etymology of šey in the adverbial counterpart warrants further investigation.

A degree verb may function as the scalar associate of adverbial aktar šey, as the examples in (27) demonstrate. Only the subject-oriented relative reading is available here, which compares Nuha to alternatives in terms of how deserving they are.

-

(27)

Eventive verbs like sing or talk offer a pluractionality associate for aktar šey, as (28) shows. Example (28a) asserts, for example, that Nuha sang more often or longer than any one else sang. With eventive verbs such as those in (28), another reading arises in addition to the subject-oriented reading shown there. Example (28a), for example, may be construed to assert that Nuha sang more than she did anything else. That is, the verb may function as focus of comparison for aktar šey, rather than the subject. Arabic is like English in that, as Heim (1995) notes, anything that may bear focus may function as the external argument of the superlative morpheme in the semantic representation. Example (28b), for example, may be construed to assert that Nuha talked during the lesson more than she talked in other situations, where focus falls on the prepositional phrase xlāl d-daris (during the lesson). The availability of such readings falls out from the flexibility in the placement of focus in adverbial superlatives. I only add for clarification here that this flexibility does not extend to adnominal aktar, because the A′ chain in the relative clause there itself licenses the superlative in those cases (Szabolcsi 1986; Farkas and Kiss 2000), preventing anything else from functioning as the focus of adnominal aktar. Since my aim here is to show that aktar šey may occur at a distance from its scalar associate, I list only subject-oriented readings below, which suffice to show this, noting that non-subject-oriented readings are available in Arabic as in English.

-

(28)

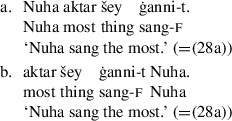

Adverbial aktar šey displays a flexibility in placement that is typical of adverbs in Arabic. This phrase can precede the main verb (29a) or occur sentence initially if the subject inverts with the verb (29b). This optionality is systematic and applies to all the examples to follow.

-

(29)

A gradable predicate adjective may also function as the scalar associate of aktar šey, as in (30).

-

(30)

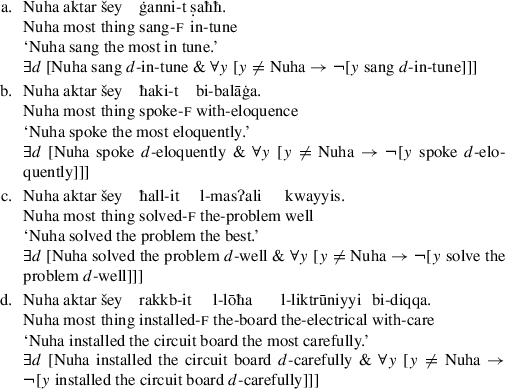

The scale for adverbial aktar šey may also be provided by a gradable adverb, illustrated in (31). In these examples, I place aktar šey before the verb to emphasize that it need not appear adjacent to the adverbial scalar associate. The most salient interpretation of an example like (31a) is that Nuha’s singing was more in tune than anyone else’s was. Having demonstrated previously that verbs like ġanna (sing) may function as a pluractional associate of aktar šey, I do not repeat the relevant translations here. Also as before, I ignore a variety of non-subject oriented readings that are available in the adverbial superlative, for example, that (31a) may be construed to assert that Nuha sang in tune more than she did other things in tune (play the violin, etc.), or that she sang in tune more than she did other things (read the paper, wash the dishes).

-

(31)

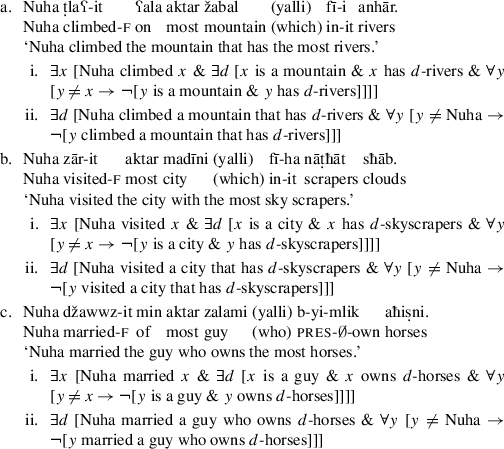

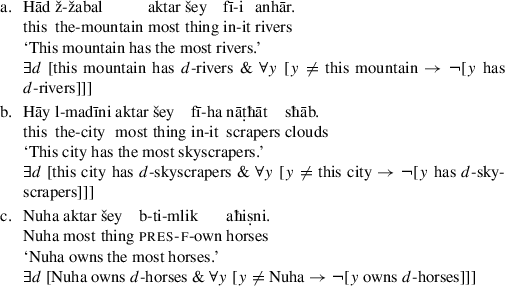

And as in the case of adnominal aktar discussed in Sect. 3, a plural or mass noun may provide aktar šey with a scale. Compare the examples in (32) below, where the plural provides a scale for adverbial aktar šey, with those in (22), where the plural in a relative clause provides a scale for adnominal aktar. This is how what Gawron (1995) calls ‘superlatives of quantity’ are formed in Syrian Arabic. The adverbial superlative aktar šey is used. The salient reading of e.g. (32a) is that Nuha stole more money than anyone else did, regardless of how many thefts she committed. This reading is logically independent of the pluractional reading, also available here, which asserts that Nuha stole money on more occasions than anyone else did.

-

(32)

As with adnominal aktar, the distinctiveness of the superlative of quantity reading from the pluractional reading is clarified by the stative examples in (33), since stative verbs like malak (own) in (33c) do not support a pluractional interpretation at all.

-

(33)

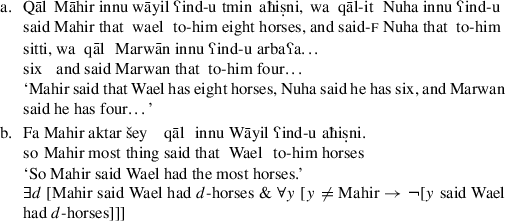

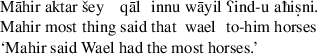

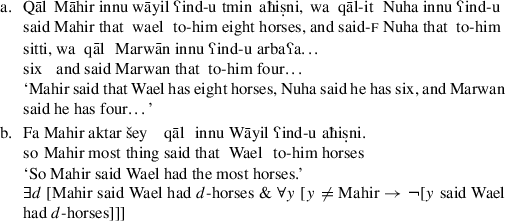

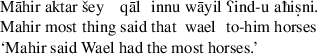

Also like adnominal aktar, the dependency between aktar šey and a scalar associate may stretch over a CP boundary, as in (34b) (cf. (25)). The superlative adverb aktar šey in (34b) may associate with the plural aħiṣni (horses) in the subordinate clause. As in the corresponding argument superlative in (25), a context like that in (34a) is critical for priming the association with aħiṣni (horses) over the more local potential associate qāl (said). In the context in (34a), for each of Mahir, Nuha and Marwan there is a number of horses they said Wael had, and the number Mahir said he had is the greatest.

-

(34)

In summary, like adnominal aktar, adverbial aktar šey may associate with any scalar term in its c-command domain (again subject to conditions described in more detail below), as schematized in (35), where XP = AP, AdvP, VP, or plural (or mass) NP. The dependency may cross a clause boundary as (34) shows. Note again, as with adnominal aktar, that the English translations to the examples above display the same interpretations as their Arabic counterparts. They differ from Arabic again in that the superlative must occur local to its scalar associate in the surface structure in English.

-

(35)

[VP aktar šey d [VP …XP d …]]

5 Constraints on displacement of aktar (šey)

This section treats the nature of the dependency between aktar (šey) and its associate. A variety of observations point to the conclusion that the dependency is a movement relation. Further, constraints on the dependency between aktar (šey) and its scalar associate in Arabic largely parallel constraints on the availability of the corresponding readings in English, lending support to an analysis of superlative interpretation in English that parallels the surface syntactic displacement seen in Arabic. Section 5.1 shows that aktar (šey) is not licensed if a constituent containing its scalar associate is pronominalized, suggesting aktar (šey) originates local to the associate. Section 5.2 finds that the dependency is interrupted by the wh- and adjunct-islands that typically interrupt A′ chains, effects that mirror constraints on the interpretation of the superlative in English. Section 5.3 finds that overt displacement of aktar (šey) in Arabic is constrained by Kennedy’s Generalization, which also constrains the interpretation of the superlative in English. Section 5.4 finds that the dependency between aktar (šey) and its scalar associate may not cross over an NP boundary, but that this constraint only constrains surface displacement. It does not hold at LF in either Arabic or English. Section 5.5 describes a locality restriction holding between the scalar term and the focus of comparison in some contexts. Lastly, Sect. 5.6 finds that the superlative cannot be interpreted lower than its surface position in Arabic. That is, the superlative is not subject to reconstruction. The absence of reconstruction is unexpected if the surface position of the superlative is derived by movement. Section 6 describes an analysis that reconciles these observations, in which aktar (šey) is itself base generated in its surface position, but its degree relation argument is derived by movement of a null operator from the position of the scalar associate. It is this operator that is subject to constraints on movement. The superlative does not reconstruct because it is not itself the element that undergoes movement. In light of this conclusion, references to ‘displacement’ in this section refer to the linear separation of aktar (šey) from its associate and are not intended to commit to any particular derivational implementation. That is the subject matter of Sect. 6.

The fact that aktar (šey) may not be separated from its associate by an NP boundary in the surface structure, as described in Sect. 5.4, means that we cannot demonstrate the existence of other constraints when the associate is within an NP, such as when it is an adjective, as in canonical quality superlatives, since here we confound the NP constraint with whatever other constraints are active. But quantity superlatives do not show the effect of this restriction in simple contexts, since the scalar associate in such cases is a plural NP itself, not a scalar term inside an NP. This allows us to circumvent the effect of NP barrierhood while investigating the effect of the other constraints discussed below. For this reason, the discussion in the subsections to follow focuses on quantity superlatives. Section 5.4 returns to this matter in more detail.

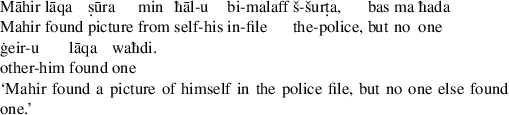

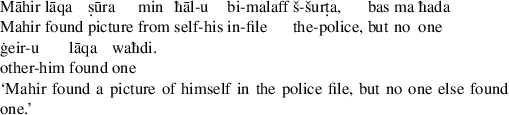

5.1 Pronominalization

If aktar (šey) stands in a movement relation to its scalar associate, then replacing a constituent containing the scalar associate with a pronoun should disrupt the association. Since the association requires base structure locality between the displaced element and its associate, aktar (šey) cannot be licensed if its associate is not present in the structure, even if it can be inferred through the reference of the pronoun. It so happens that neither CP nor VP is subject to pronominalization in Arabic, which limits the contexts in which we can test this prediction. However, Arabic has a pro-NP wāħid (one, feminine waħdi) that makes it possible to test this prediction with adnominal aktar. First, like English one, wāħid may replace a constituent containing a bound pronoun, as (36) demonstrates. There, the phrase waħdi is anteceded by the grammatically feminine NP sūra min ħālu (picture of himself). At LF, waħdi is interpreted as a copy of its antecedent. The anaphor ħālu (himself) may be bound by its local antecedent ma ħada ġeiru (no one else; ħada is the negative polarity variant of wāħid) in the copy, meaning that no one other than Mahir found a picture of himself (the ‘sloppy’ reading). Or it may refer to Mahir and assert that no one other than Mahir found a picture of Mahir (the ‘strict’ reading). On the sloppy reading, the variable himself has a different index in the copy than it has in the antecedent (Ross 1967; Fiengo and May 1994).

-

(36)

In light of the possibility of re-indexation, the ungrammaticality of the continuation in (37a) for (37) is unexpected. Example (37) introduces a set of boys who found shells on the beach as a potential antecedent for wāħid in (37a). So (37a) should be synonymous with (37b), which has the phrase šabb (yalli) lāqa ṣadfāt (boy who found shells), which also denotes that set, where wāħid occurs in (37a). The movement analysis of the distribution of aktar presents an explanation for the fact that (37a) is ungrammatical. For aktar to occur in (37a), it would have to have been displaced from a position local to its scalar associate. But its scalar associate is not present in the syntax, since it is in the constituent replaced by wāhid. Consequently, aktar cannot be licensed. Variable re-indexing is possible in (36) because the relationship between an anaphor and its antecedent does not involve movement. The contrast between (36) and (37) therefore supports the claim that the relationship between aktar and its scalar associate involves movement.

-

(37)

5.2 Island conditions

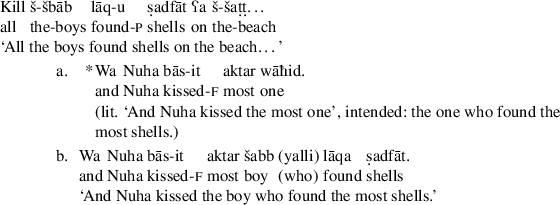

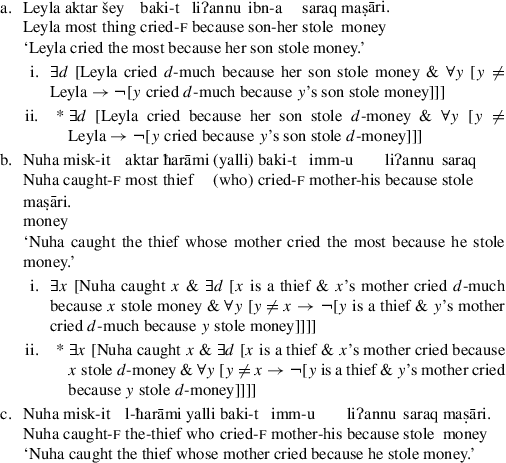

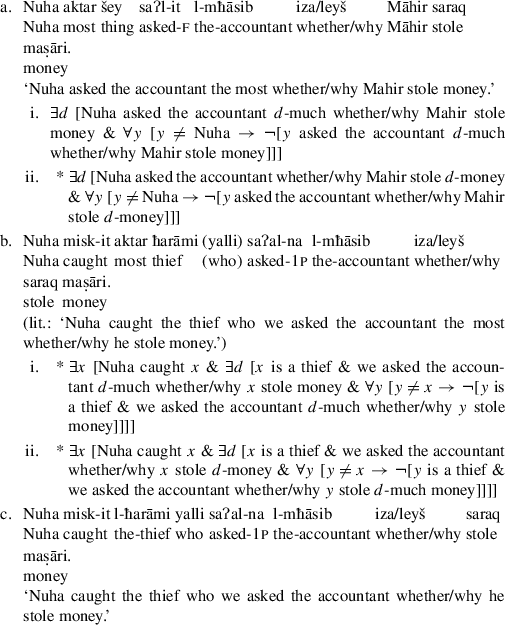

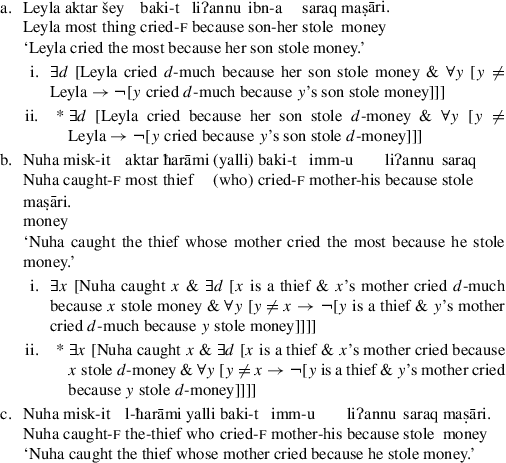

If aktar (šey) stands in a movement dependency with its scalar associate, we expect this dependency to be subject to constraints on movement. Ross (1967) notes that adjunct clauses and interrogative clauses are ‘islands’ to movement. A term may not normally move from a position inside an island to a position outside the island. Consequently, we do not expect the dependency between aktar (šey) and its associate to cross over an adjunct or interrogative clause boundary. We have seen that the declarative complement clause in (25) is transparent to the relationship between adnominal aktar and its associate. Example (34b) shows the same for adverbial aktar šey. In contrast, the adjunct clauses in (38a) and (38b) block the dependency between aktar (šey) and its associate. For example, if Marwan’s mother cried because he stole 500 liras, and Muen’s mother cried because he stole 600 liras, and Khalid’s mother cried because he stole 700, we cannot say (38a) if Leyla is Khalid’s mother, nor (38b) if Nuha caught Khalid. This—ungrammatical—interpretation is spelled out in (ii). The example in (38c) is provided as a control to (38b) to show that the relative clause itself is grammatical without aktar, so the problem in (38b) is the licensing of aktar, not the licensing of the relative pronoun itself. Another reading is available for (38a) and (38b), shared by the English translations there and spelled out under (i), where aktar (šey) associates with the pluractionality of the local verb baka (cry). But association of aktar (šey) with an associate inside the adjunct clause is not possible.

-

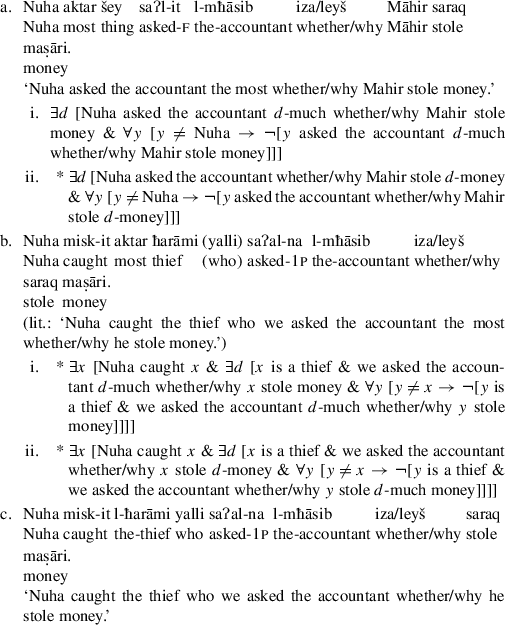

(38)

Similarly, the interrogative complement clauses in (39) block the dependency between aktar (šey) and its associate. If Khalid asked the accountant whether (or why) Mahir stole 500 liras, Marwan asked whether/why he stole 600, and Nuha asked whether/why he stole 700, we cannot describe this situation by saying (39a). The (ii)-reading of (39a) is ungrammatical. As expected, (39a) is grammatical when aktar šey associates with pluractionality of the verb saʔal (ask), a local associate (i). Similarly, if we asked the accountant whether Marwan stole 500 liras, whether Muen stole 600 and whether Khalid stole 700, and Nuha caught Khalid, we cannot describe this situation by saying (39b). Again, (39c) provides a control for (39b) and demonstrates the relatively unrestricted nature of ‘referential’ A′ chains in Arabic, as described by Aoun and Benmamoun (1998) and Aoun et al. (2010). Even so, non-referential chains in Arabic are strongly restricted by island conditions and the dependency between aktar (šey) and its associate patterns like a non-referential chain in failing to cross out of the wh-island, blocking the (ii)-reading of (39a) and (39b). Unexpectedly, the local (i)-reading is also ungrammatical in (39b), for reasons unrelated to the wh-island that I discuss fully in Sect. 5.5.

-

(39)

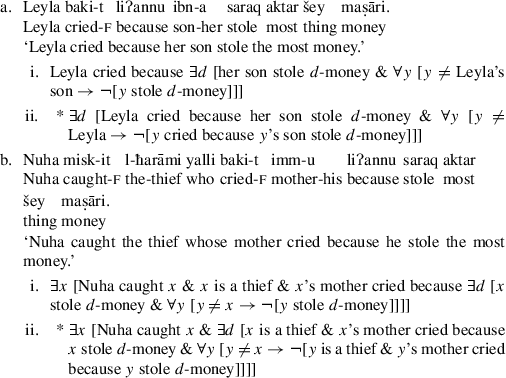

The observations above show that the dependency between aktar (šey) and its scalar associate may not cross over an island boundary, which is characteristic of movement chains. These observations therefore support the claim that the position of aktar (šey) in grammatical long distance displacement examples like (25) and (34b) is derived by displacement from a position local to the scalar associate. Not only do the islands illustrated above disrupt the dependency between aktar (šey) outside the island and an associate inside the island, they also disrupt LF movement of aktar (šey) from inside an island to a scope position outside the island, just as in English. In each of the examples below, aktar šey occurs in a syntactic island, and can be interpreted in that position, illustrated in the (i)-reading of each of the examples below. The (ii)-reading is not available though, where aktar šey has scope external to the island. Hence, (40a) may assert that Leyla cried because her son stole more money than anyone else did (i), but not that she cried because her son stole a specific amount of money d and other mothers cried because their sons stole specific amounts of money, and these amounts happen to be less than d (ii).

-

(40)

-

(41)

In English as well, the superlative the most inside the island in the translations to the examples above cannot be interpreted along the lines of the (ii)-readings stated there. In both English and Arabic, islands block LF movement of the superlative. In Arabic, they block surface displacement as well. Displacement of the superlative appears to be uniformly restricted by island conditions in the two languages, whether overt (Arabic) or covert (Arabic and English).

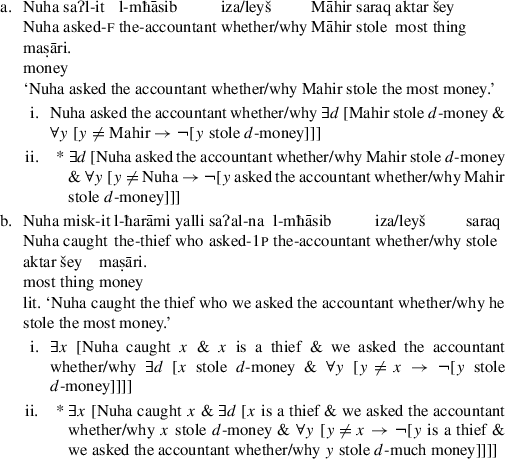

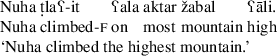

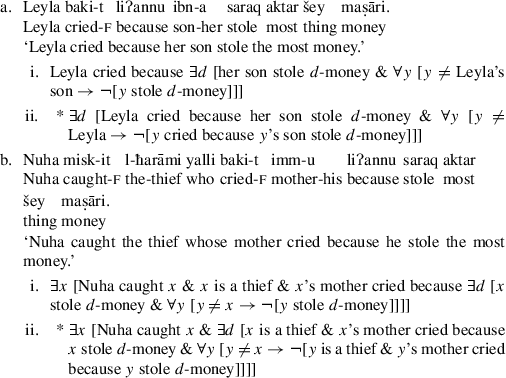

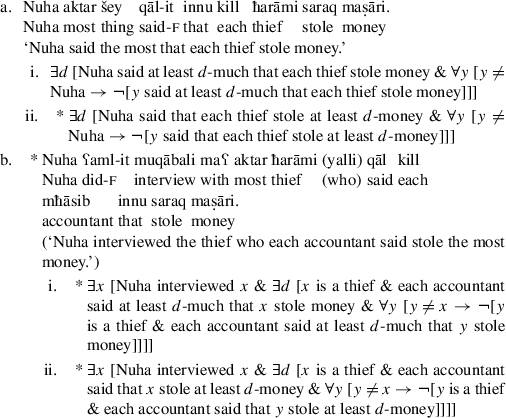

5.3 Kennedy’s Generalization

Superlative displacement in both English and Arabic also obeys a condition that Heim (2001) calls ‘Kennedy’s Generalization’, after observations by Kennedy (1999). As Heim puts it, a degree operator cannot have scope over a quantifier that c-commands its associate. In (42a), aktar šey cannot bind the scalar associate maṣāri (money) because of the intervening quantifier kill ħarāmi (each thief). Consequently, the reading in (i) is possible, where aktar šey associates locally with qālit (said), but not the reading in (ii), where aktar šey associates long-distance with maṣāri (money). In the ungrammatical LF (ii), the amount that Nuha attributed to the least successful thief is greater than the amount anyone else attributed to the least successful thief. I add ‘at least’ to the LFs below to help the reader decipher the rather odd reading that the (ii)-formulas express. I emphasize that these readings are unavailable in Arabic, not simply strange. Similarly, adnominal aktar is unable to bind the scalar associate maṣāri in (42b). There is no possibility of interpreting (42b) as the assertion in (ii), which describes a situation in which Nuha interviewed a thief for whom it is the case that no accountant attributed a smaller theft to him than any accountant did to any other thief. In fact, (42b) is altogether ungrammatical because the other, local, reading, where aktar associates with the pluractionality of the verb qālit (said), as it may in (42a), is not available here either, for reasons described in Sect. 5.5 not related to Kennedy’s Generalization.

-

(42)

As with other islands discussed above, Kennedy’s Generalization restricts LF displacement as well as overt displacement in Arabic. When atkar šey occurs in the domain of a quantifier, as in the examples below, it may not have scope over the quantifier. The quantifier blocks movement of the superlative to a position corresponding to its position in the examples in (42), just as the quantifer blocks the superlative in (42) from binding a scalar associate in the domain of the quantifier, whence the ungrammaticality of the (ii)-readings below. The in situ reading of aktar šey schematized in the (i)-reading of (43a) below is contradictory, since if one of the thieves stole the most money, the others can’t have also stolen as much. But this contradictory reading is available for (43a); it is not ungrammatical. The contradiction does not arise in (43b), where on the (i) reading, the report that the accountants agree on who stole the most money is contentful.

-

(43)

Note that the examples in (43) are parallel to their English translations there, which also do not admit the (ii)-readings. The constraint at work here, originally observed independently as a restriction on the LF scope of degree operators in English, constrains both the surface displacement of Arabic aktar (šey) from its scalar associate (42), and covert LF displacement as well (43), in the latter case just as in English. This observation once again supports the parallel between Arabic and English seen with respect to other constraints described above. What is not a possible LF in English is not a possible surface structure in Arabic.

A reviewer of the present work points out that these observations are significant for the theory of intervention effects for syntactic dependencies. Beck (1996) demonstrates that quantifiers are intervenors for wh-movement at LF but not in the surface structure. That is, they interrupt covert but not overt wh-movement. As far as English goes, this claim subsumes Kennedy’s Generalization, since on the movement approach superlative movement is a type of covert A′ movement. In Arabic, though, it seems overt displacement of the superlative over a quantifier is also blocked, which is unexpected if quantifiers only interrupt covert movement. Beck (2012) presents a focus-theoretic analysis of the intervention effect, according to which both wh-phrases and quantifiers are focus sensitive elements that interrupt the projection of focus-semantic values of lower constituents, though she notes the existence of a residue of cases that her analysis does not subsume. Consequently, Kennedy’s Generalization could be one of those cases, the result of restrictions not related to focus projection. Or alternatively, the Arabic facts may be showing us that focus-intervention restricts both overt and covert movement in principle (as we would expect), but some unknown factor selectively facilitates overt wh-movement over a quantifier. A resolution to these issues will require further research.Footnote 4

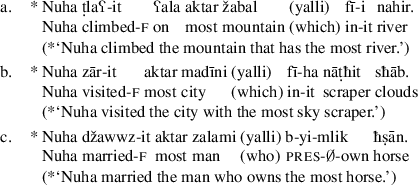

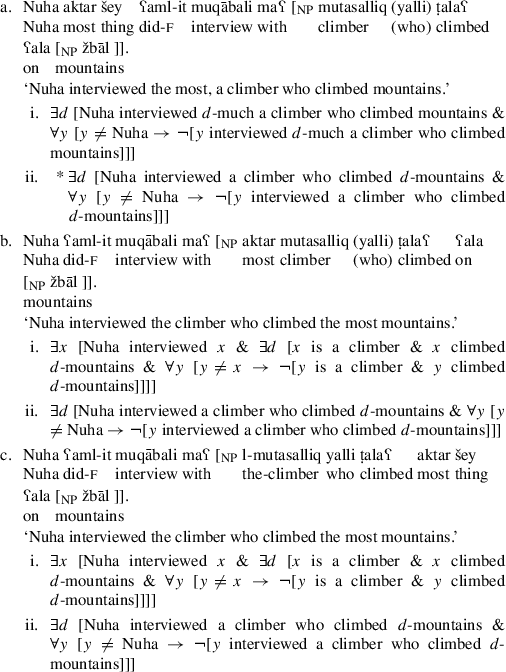

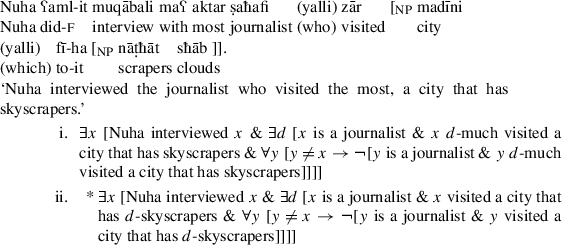

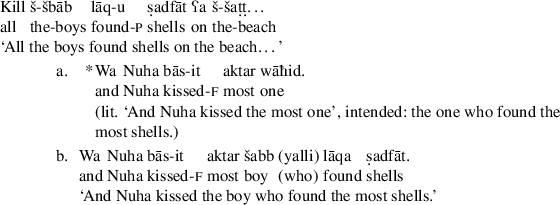

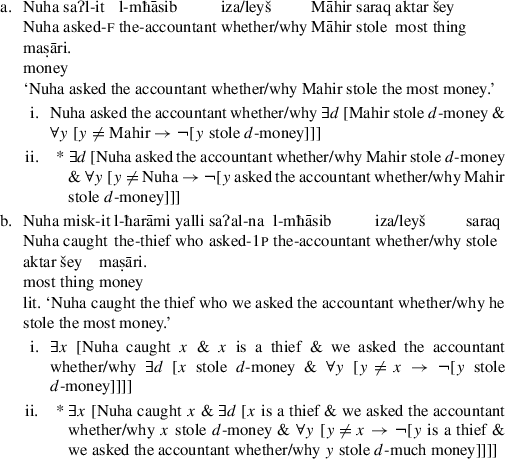

5.4 The NP Constraint

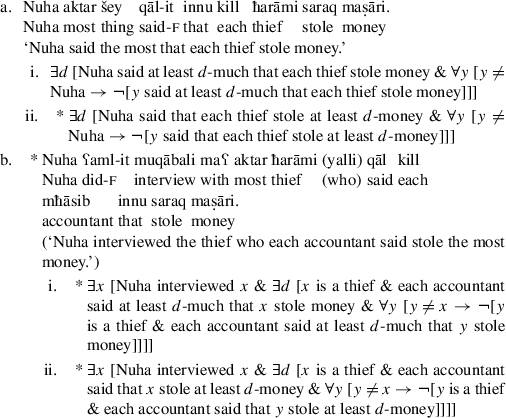

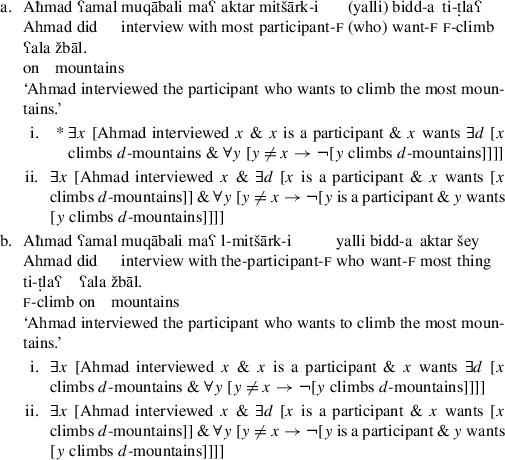

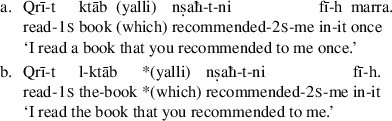

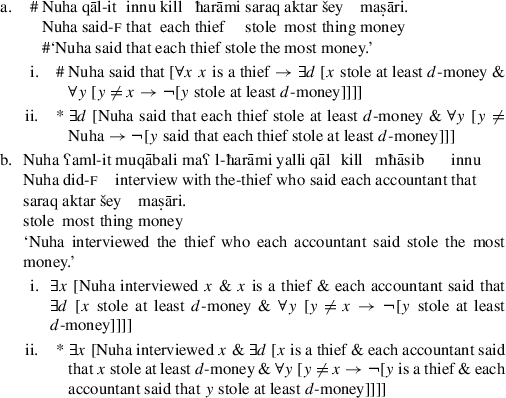

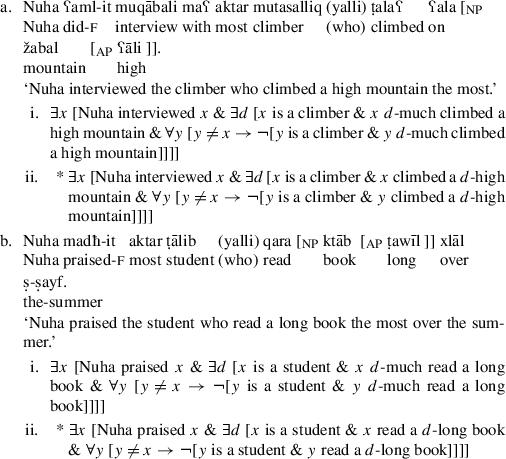

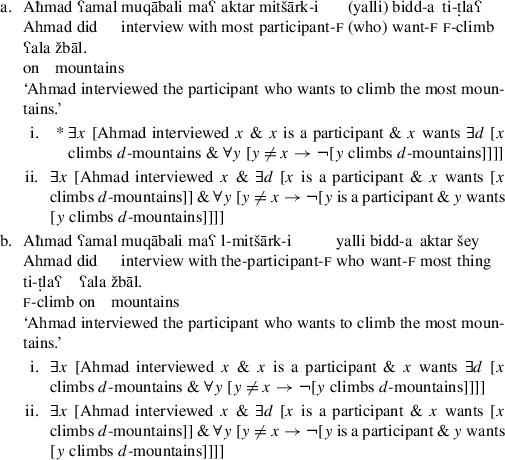

The data we have seen so far suggest that any scope position for the superlative in Arabic is also a possible surface position for either aktar or aktar šey, depending on whether the position is adnominal or adverbial. We have also seen that constraints that restrict covert scope displacement for the superlative, such as island conditions and Kennedy’s Generalization, also restrict the overt displacement of aktar (šey). In light of this correspondence between the overt and covert displacement of aktar (šey), we expect the subject-oriented relative reading afforded to aktar in examples like (44a), which involve LF raising of aktar on the movement account, to have an overt counterpart with aktar šey in the matrix clause, like (44b) for (44a). This is, after all, what we see in the superlative of quantity in examples like (44c). However, (44b) is only grammatical on a pluractional reading (i), where it asserts that Nuha climbed a high mountain more often than anyone else did. The adjective ʕāli (high) is not accessible as a scalar associate in the configuration in (44b), though again, the plurality of the noun in (44c) is, as spelled out in (ii) (example (44c) also supports a pluractionality associate like the other examples, spelled out in (i); this reading is not relevant here).

-

(44)

In (44b), aktar šey is not able to bind the degree argument of the scalar adjective ʕāli (high), which is contained in the NP žabal ʕāli (high mountain). In (44c), aktar šey is able to bind the quantity argument of the plural noun žbāl (mountains). Insofar as the plural noun functions as the head of the NP that contains it and therefore projects its features to the phrasal level, the scalar associate of aktar šey in (44c) is the plural NP itself (on the relevant reading, that in (ii)). This plural NP is not itself contained in an NP. This pattern suggests that the dependency between aktar šey and its scalar associate may extend to, but not cross over, an NP category boundary in the surface structure, a restriction I refer to as the ‘NP Constraint’. Adnominal aktar in (44a) is contained in the NP that contains its associate ʕāli (high), and therefore this dependency does not cross over an NP category boundary.Footnote 5 If this is correct, the restriction in question applies only in the surface structure, since an LF where the superlative occurs in the position of aktar šey in (44b) but binds the adjective is available to (44a), since (44a) has a subject-oriented relative reading spelled out in (ii), which on the movement account is derived by movement of the superlative out of the NP.

Example (45a) confirms this generalization. Though aktar šey may bind a plural NP in principle, as in (44c), that NP may not occur within another NP, for example, within a relative clause that aktar šey is external to, as illustrated in (45a). The example is grammatical on a local reading of aktar šey, one of which compares Nuha with others in terms of how much interviewing they did, as paraphrased in the (i)-reading of (45a). But it is ungrammatical on a reading where it compares Nuha to other interviewers in terms of the number of mountains their interviewees climbed (the (ii)-reading). That is, aktar šey in (45a) cannot be construed as having originated within the NP headed by mutasalliq (climber) and therefore cannot be construed as having originated in a local relationship to the plural žbāl (mountains). Since the NP Constraint does not apply to covert movement, the counterparts in (45b) and (45c) display both a low reading corresponding to their surface structure (i) and a high reading derived by covert movement of aktar (šey) out of the relative clause (ii).

-

(45)

The NP-Constraint is not sensitive to the category of the scalar associate. It blocks association of aktar šey with a degree verb (46a) and a gradable adverb (46b) as much as with a plural noun (45a)

-

(46)

The ungrammatical readings of the sentences above, including (44b), share the structure schematized in (47), in which an NP category boundary intervenes between aktar šey and its scalar associate. As mentioned above, this constraint only applies to overt displacement of aktar šey from its scalar associate. The configuration that (45a) displays on the surface is identical to the configuration that derives the relative (ii)-reading of (45b) and (45c) at LF. Therefore, covert displacement of aktar (šey) may cross over an NP boundary, but overt displacement may not. Arabic is subject to constraints on overt displacement that do not apply to covert displacement. In this respect, Arabic resembles English to some extent, in that covert displacement is freer than overt displacement. The term šey is in parentheses because the same constraint applies to adnominal aktar, as described below.

-

(47)

The NP Constraint (applies in surface structure only):

*[…aktar d (šey) …[NP …XP d …]]

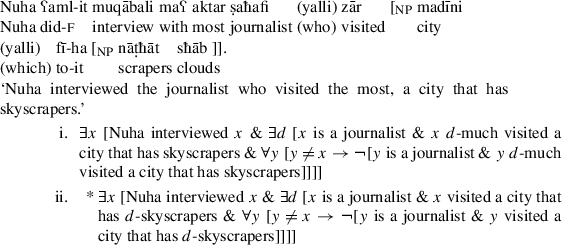

Like adverbial aktar šey, adnominal aktar may not be separated from its scalar associate by an NP boundary, and once again this constraint only applies to surface displacement. NP is transparent to LF displacement. For example, adnominal aktar may not bind the degree argument of the adjective ʕāli (high) in the phrase žabal ʕāli (high mountain) in (48a), blocking any reading where aktar associates with ʕāli such as that in (ii). The only readings available are readings where aktar has a local associate, such as the quantity argument of the verb phrase ʕamlit muqābali (did an interview), as spelled out in (i). Example (48b) is parallel to (48a). In both cases, an NP boundary blocks association of aktar with an adjective inside the NP.

-

(48)

Accordingly, aktar cannot associate with the plural nāṭħāt sħāb (skyscrapers) in a relative clause that aktar is itself external to (49). The term aktar may only have a local reading illustrated in (i), but no reading where it compares individuals in terms of quantities of skyscrapers, as in (ii). Similar examples can be constructed that illustrate the inability of adnominal aktar to bind other kinds of scalar associates (degree verbs, gradable adverbs) inside a secondarily embedded relative clause. However, it turns out that (49) and similar examples are subject to an independently observable constraint that in these cases subsumes the NP Constraint, described in the following section.

-

(49)

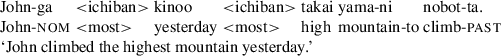

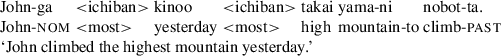

I conclude this discussion of the NP Constraint with two cross-linguistic remarks. Firstly, English vacuously obeys the NP Constraint, since it obeys a much more restrictive constraint on the surface distribution of the superlative. The English superlative morpheme must appear affixed to (in the form of est) or adjacent to (in the form of most) its scalar associate. The NP Constraint might therefore also be active in English, but not observable. If so, Arabic and English differ only in that the superlative may be displaced from its associate in the surface structure in Arabic, while the English superlative cannot be displaced in the surface structure at all. At LF they are entirely uniform. Secondly, Aihara (2009) observes that the Japanese superlative morpheme ichiban may be displaced from its scalar associate, as (50) illustrates. The term ichiban may occur either before or after the VP-adjunct kinoo (yesterday), and receives a relative or absolute interpretation accordingly. This placement optionality mimics the flexibility in placement seen for Arabic aktar šey. However, the occurrence of ichiban before the adverb in (50) is the equivalent of a structure that is actually ungrammatical in Arabic on account of the NP Constraint (cf. (44b)). Arabic adverbial aktar šey cannot bind an associate inside an NP, as ichiban may in (50). It appears therefore either that the NP Constraint is not universal, or perhaps that Japanese DP/NP structure differs from Arabic in ways that obviate the NP Constraint in Japanese. A more careful comparison of Japanese and Arabic will be required to resolve this issue.

-

(50)

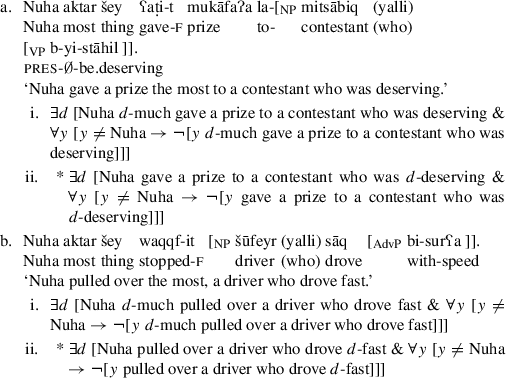

5.5 The Clausemate Requirement

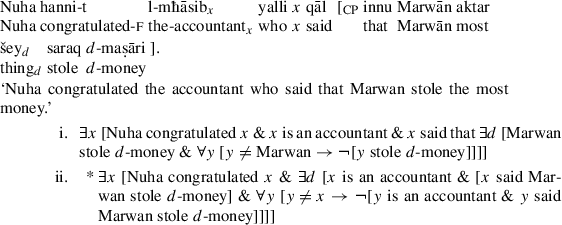

A reviewer of the present work points out that (25), repeated in (51a) below, is similar to (51b), but yet the two sentences do not equally allow the indexing shown there. As discussed in Sect. 3, (51a) holds true if the accountant said how much money each thief stole, and for some thief, the amount of money the accountant said he stole is greater than the amounts the accountant said the other thieves stole, and Nuha caught this thief (a subject-oriented relative reading is also available, but not relevant to the issue at hand). This reading corresponds to the surface structure in (51a). No analogous reading is available for (51b). This sentence cannot be read to compare the accountant with alternatives in terms of how much money they said that Marwan stole. A local reading is available for (51b) that compares the accountant with alternatives in terms of how often they said that Marwan stole money, that is, where aktar binds the quantity argument of the verb qāl (said) (not shown).

-

(51)

The reviewer who notes this contrast points out that (51a) and (51b) differ in the distribution of the individual and degree variables x and d. In (51a), the nominal restriction of aktar (namely ħarāmi (thief)) binds a variable in the same minimal clause as the variable that aktar binds, the quantity argument of maṣāri (money). This clause is the bracketed CP in (51a). In (51b), the variable that aktar binds is in a different minimal clause than the variable that aktar’s nominal restriction mħāsib (accountant) binds. This appears to be the offending fact about (51b) that blocks the association of aktar with maṣāri.

The restriction at work here, then, is that adnominal aktar and its nominal restriction must bind a variable in the same minimal clause. I refer to this as the ‘Clausemate Requirement’. This constraint also applies to (49), which I introduced as an instance of the NP Constraint. On the grammatical reading mentioned there, where (49) asserts that the interviewee visited cities with skyscrapers more than anyone else visited cities with skyscrapers, the head of the relative clause originates in the same minimal clause as the scalar associate zār (visit), which licenses this reading. On the ungrammatical reading, the head of the relative clause originates in a separate minimal clause as the associate of aktar. However, it does not appear that the Clausemate Requirement subsumes the NP Constraint in general, for reasons discussed below.

As the reviewer who notices the contrast in (51) also points out, the constraint does not apply to adverbial aktar šey in (34b), repeated in (52) below. This example has a reading where aktar šey associates with aħiṣni (horses) and compares Mahir with others in terms of the degree relation λdλx x said that [Wael has d-horses]. Here, the degree variable d is in a different minimal clause than the individual variable x, but the result is grammatical.

-

(52)

This could be taken to mean that the Clausemate Requirement only applies to adnominal aktar, not adverbial aktar šey. But it appears instead that the Clausemate Requirement only applies in relative clauses, which configurationally distinguishes (52) from (51b). In (51b), aktar binds a degree variable in a relative clause. The Clausemate Requirement requires that the head of this relative clause bind a variable in the same minimal clause that the degree variable occurs in. No relative clause occurs in (52). That the relative clause is the critical factor is confirmed by the observation that when aktar šey occurs in a relative clause, the possibility of covert raising to a higher scope position is restricted by the Clausemate Requirement. Example (53) is parallel to (51b) except that adnominal aktar in the latter is replaced by aktar šey in a position local to its associate within the relative clause. Like the counterpart example in (51b), no reading is available here that compares the head of the relative clause (the accountant in (53)) to alternatives in terms of the amount of money they said that Marwan stole (ii). On the movement account, such a reading requires movement of aktar šey to a position corresponding to the position of adnominal aktar in the corresponding example in (51b). The Clausemate Requirement blocks this covert movement just as it blocks the corresponding examples with overt movement.

-

(53)

In light of these observations, the correct formulation of the Clausemate Requirement appears to be that in (54).

-

(54)

Clausemate Requirement:

The configuration λdλx…[Rel Cl …x …d …] is only grammatical when x and d occur in the same minimal clause.

Example (53) demonstrates another aspect of the Clausemate Requirement that critically distinguishes it from the NP Constraint. Like the other constraints on movement discussed in Sect. 5.2, the Clausemate Requirement applies both in the surface structure, as in (51b), as well as at LF, as in (53); it restricts both overt and covert displacement. We have seen that the NP Constraint, in contrast, only applies in the surface structure; it does not restrict covert displacement. It therefore does not appear to be possible to reduce the NP Constraint to the Clausemate Requirement.

The Clausemate Requirement also holds in English. The English translation to (51a) is like Arabic in allowing a ‘high’ reading of the superlative that compares thieves in terms of how much money the accountant said they stole. And the English translation to (53) is also like its Arabic counterpart in failing to display a reading that compares accountants in terms of how much money they said Marwan stole. The unavailability of this reading in (53) is reflected in the ungrammaticality of the corresponding surface placement of aktar in (51b) (with associate maṣāri (money)). Here again, therefore, English and Arabic are identical in terms of the availability of scope readings for the superlative, which are reflected in surface placement options in Arabic (modulo the NP Constraint).Footnote 6

5.6 Reconstruction

The facts described above suggest that aktar (šey) stands in a movement relation with a position local to its scalar associate in Arabic. The evidence reviewed in this section indicates that aktar (šey) may have scope at or higher than its surface position (subject to constraints on displacement), but not lower than its surface position. This observation casts doubt on the most obvious implementation of the movement analysis for Arabic—that aktar (šey) itself undergoes movement—and suggests instead that aktar (šey) is base generated in its surface position, while its relation to its scalar associate is derived by movement of a null abstraction operator. It remains evident that aktar (šey) may undergo LF movement from its surface position.

Operator-variable dependencies formed by movement, particularly A′-movement, are typically characterized by the possibility of interpreting the operator as if it were in the position of the variable, that is, as if it had never moved, a phenomenon termed ‘reconstruction’ by Chomsky (1977), Barss (1986) and others. If the surface position of aktar (šey) is derived by movement, we expect the chain so derived to show reconstruction effects. This expectation is not borne out, requiring a reinterpretation of what moves in this construction, as I describe in more detail below and in Sect. 6.

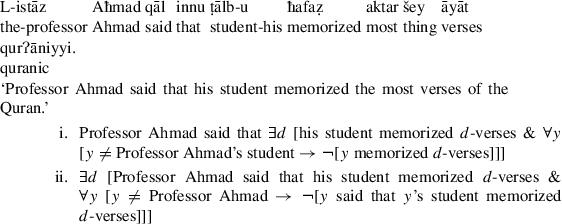

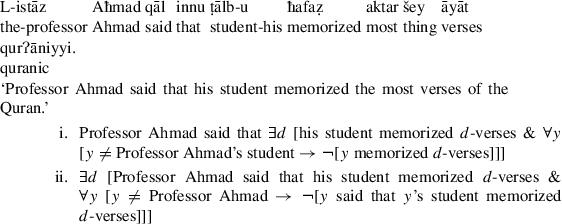

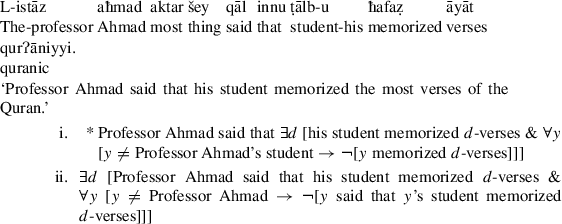

Consider the context sketched in (55), where each teacher said that his student memorized so-and-so many verses of the Quran, but also claimed explicitly that his student memorized more verses than anyone else’s student.Footnote 7

-

(55)

-

Prof. Ahmad said that his student memorized 200 verses of the Quran, and also that no one else’s student memorized that many.

-

Prof. Rashid said that his student memorized 300 verses of the Quran, and also that no one else’s student memorized that many.

-

Prof. Fareed said that his student memorized 400 verses of the Quran, and also that no one else’s student memorized that many.

-

On the surface scope reading of (56), spelled out in (i) below, aktar šey is interpreted as part of the semantic content of the subordinate clause, that is, as part of what the teacher in question said. Since in the context in (55), each teacher asserted that his respective student memorized more verses than any other student, the assertion in (i) is true, of Ahmad and the other teachers as well. As in previous examples, a high reading of aktar šey in (56) is also available, spelled out in (ii), which asserts that Ahmad said that his student memorized a certain number of verses, and, possibly unbeknownst to Ahmad, this just happens to be more than what the other teachers said their students memorized. Only Fareed meets this condition in the context in (55), meaning that (56) is false on this reading (ii) in this context.

-

(56)

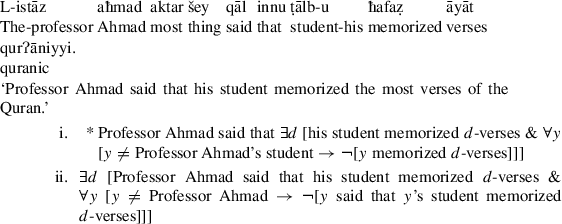

Reading (ii) described for (56), where we compare professors in terms of how many verses they claimed their students memorized, is also available for (57), where it corresponds to the surface scope reading of aktar šey, where aktar šey occurs in the matrix clause. If aktar šey has moved to this surface position in (57) from a position local to the associate within the subordinate clause—more or less the position it occurs in (56)—then we expect reconstruction to derive the reading in (i), where aktar šey is interpreted in the subordinate clause, as part of what the teacher in question said. This is the reading corresponding to the surface placement of aktar šey in (56), which we observed was true in the context in (55), since Ahmad asserted that his student memorized more verses than anyone else (as did the other teachers). Consequently, if reconstruction is available, then (57) has a reading which is true in the context in (55). This judgement should be relatively easy to make, since the surface scope reading is false in this context, since the number of verses that Ahmad claimed his student memorized did not in fact exceed the number of verses the other teachers claimed their students memorized; reconstruction is the only way of making (57) true in the context in (55). Crucially, however, native speakers do not judge (57) to be true in this context. They explicitly reject a reading corresponding to the salient reading of (56), where Ahmad asserts that his own student memorized more verses than the other teachers’ students. This judgment means that a ‘low’ reading of aktar šey corresponding to the logical form in (i) is not available as a possible interpretation of (57). Reconstruction is not possible.

-

(57)

The absence of reconstruction can also be observed in examples similar to Heim’s illustration of the upstairs de dicto reading of the superlative (5). Consider in this connection the context in (58), where Nuha wants to climb four mountains but also wants no one else to climb as many mountains, that is, she wants to beat the others by climbing four mountains. Mona and Layla want to climb six and eight mountains respectively but have no desires about the other climbers.

-

(58)

-

Nuha wants: Nuha climbs 4 mountains and no one else climbs 4 mountains.

-

Mona wants: Mona climbs 6 mountains.

-

Layla wants: Layla climbs 8 mountains.

-

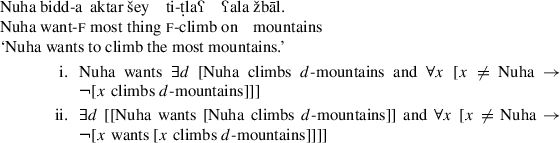

In (59), aktar šey occurs after the modal verb bidda (want). This ‘low’ placement in (59) allows both a ‘low’ reading (i) where it asserts that Nuha wants to beat the others at mountain climbing, which is true in the context in (58), and a ‘high’ reading (ii) where it asserts that the number of mountains Nuha wants to climb exceeds the number of mountains the other climbers want to climb, which is false in the context in (58).

-

(59)

In (60), aktar šey occurs before the modal verb bidda (want). This ‘high’ placement of aktar šey allows the ‘high’ reading in (ii), where we compare Nuha with other climbers in terms of how many mountains they want to climb. This interpretation of (60) is false in the context in (58), since the number of mountains Nuha wants to climb does not exceed the number of mountains that the other climbers want to climb. On the other hand, the ‘low’ reading spelled out in (i) makes a true assertion in the context in (58), namely that Nuha wants to beat the others at mountain climbing. However, the sentence in (60) is judged false in this context, meaning that the true assertion in (i) is not available as a possible interpretation of (60). The false assertion in (ii) is the only possible interpretation of (60). That is, reconstruction of aktar šey to a lower position is not possible.

-

(60)

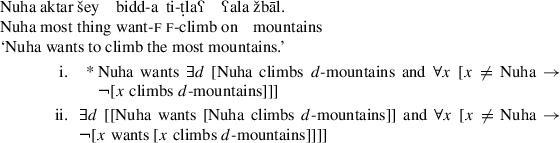

Like adverbial aktar šey, adnominal aktar also fails to reconstruct. If Ahmad interviewed Nuha in the context in (58), (61a) is false. Since reconstruction of aktar to a position within the want-clause would derive the true assertion in (i), reconstruction appears to not be available in (61a). In contrast, the low placement of aktar šey in (61b) is true under these circumstances, though the higher reading is also available, as expected, albeit false in the context in (58). As expected, a subject-oriented relative reading is available to aktar (šey) in both cases, where we compare Ahmad with other interviewers in terms of the number of mountains their respective interviewees want to climb (not shown).

-

(61)

These observations implicate the generalization that aktar (šey) has scope at or above its surface position. This fact represents a conundrum for the movement account. The dependency between aktar (šey) and its scalar associate is configurationally constrained and thwarted by pronominalization of a site containing the associate. This much implicates a derivational view of the surface distribution of aktar (šey). On the other hand, if the derivational view is correct, we expect the chain derived by movement to show reconstruction effects, but the discussion above indicates that the chains headed by aktar (šey) do not reconstruct. One possible conclusion is that we are dealing with a type of movement chain that does not reconstruct. While this is conceivable, I attempt in the following section to construct an analysis that explains the failure of reconstruction for this dependency.

6 Analysis