Abstract

The reported high rates of deaths and negative psychological outcomes of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic have led to an increased empirical interest in examining the contributing factors of coping during the COVID-19 pandemic. Adolescents living in Arab societies have unique challenges that may increase the likelihood of exhibiting symptoms of stress during this crisis. However, this population has been understudied in this context. The current research aims to elucidate factors that may contribute to Arab Israeli-Palestinian students’ coping abilities during the COVID-19 pandemic by investigating the relationship between coping with stress during the COVID-19 outbreak and both self-control and religiosity. To our knowledge, the present study is the first to investigate the relationship of coping with stress during the COVID-19 outbreak with self-control skills and religiosity among Arab Israeli-Palestinian college students in Israel (n = 465). Correlational analyses and stepwise multiple regression models were used to examine these relationships. The stepwise multiple regression model demonstrated that (1) higher levels of self-control (β = .19, p < .01) and religiosity (β = .16, p < .01) predicted higher levels of adaptive, problem-focused coping, and (2) higher levels of self-control (β = −.21, p < .01) and religiosity (β = −.17, p < .01) predicted lower levels of maladaptive, emotion-focused coping. Thus, the current research demonstrates the importance of these variables in countering stress resulting from the COVID-19 outbreak in non-Western societies. These findings are consistent with previous literature that has addressed the impact of self-control and religiosity in improving coping behaviours in Western societies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak has persisted since the end of 2019, and many countries across the globe continue to cope with the consequences of this pandemic. Major consequences have included persons’ physical and mental health, finances, employment, and social relations. Specific attention has been devoted to understanding the negative psychological outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic (Dubey et al., 2020). This pandemic has ultimately affected people’s psychological and mental well-being by causing, among other factors, mass hysteria, economic burden, and financial losses.

The mass fear of COVID-19, termed “Corona phobia,” (Heiat et al., 2021, pp. 361–367) has generated many negative psychiatric manifestations across social groups, including symptoms of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (Dubey et al., 2020). For example, one study of individuals living in Wuhan, China, showed prevalence rates during COVID-19 were high for depression (48.3%), anxiety (22.6%), and the co-occurrence of depression and anxiety (19.4%) (Gao et al., 2020).

The purpose of the current study is to examine the contribution of personal and social resources as coping factors during the COVID-19 pandemic for Palestinian-Israeli students, which are part of a unique and understudied population. More specifically, the study focuses on how coping with the psychological and mental health implications of the COVID-19 pandemic was impacted by self-control skills and religiosity, particularly within the religious and cultural context of the Arab Palestinian minority living in Israel. Studies conducted around the world and, in particular, in the Palestinian population, indicate the positive contributions that personal factors like self-control and religiosity have towards predicting individuals’ mental welfare; these variables are specifically effective when confronting risk behaviours and different stressful situations (Agbaria & Natur, 2018; Agbaria & der, 2019; Mansdorf et al., 2020). For instance, Mansdorf et al., (2020) surveyed 131 Arab adults living in Israel at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic (April–May 2020). These participants reported, on average, that their general psychological health was not significantly different than their typical levels of functioning (Mansdorf et al., 2020). Additionally, Mahamid and Bdier (2021) studied 400 Palestinian adults regarding their response to the COVID-19 pandemic. They found positive religious coping had a significant negative correlation with depressive symptoms and perceived stress.

Limited research exists examining the individual characteristics predictive of the abilities of Arab adults living in Israel to cope with COVID-19. A 2021 study investigated the relationship of personality and support groups with coping with the beginning of COVID-19 stress (Agbaria & Mokh, 2021). The study demonstrated that one’s ability to effectively cope was increased by having positive social support. Further, another study explored the religious and personal resources incorporated by Palestinians living in Israel to cope with stress from the COVID-19 pandemic (Agbaria & Mokh, 2022). Using a self-report questionnaire, it was found that Palestinian adults relied on their faith in God and self-control as two of the resources implemented for coping with the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, no studies have assessed the contribution of self-control and religiosity to COVID-19 coping within the Arab adult population in Israel. Therefore, the present research builds upon prior findings to assess whether these resources will contribute positively to coping with the psychological and mental health implications of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Coping with COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic is substantially changing what is familiar to us in our daily lives. Although the mass quarantine proposed by many countries in response to this global outbreak helped contain the pandemic by reducing the number of people infected with COVID-19, many fear the potential intensification of mental health problems during this period. Individuals in crisis are highly prone to experience increased levels of stress, tension, and anxiety. Nevertheless, various types of stressors affect people differently depending on the individual’s coping abilities and capabilities (Byrd & McKinney, 2012).

Studies in China offer preliminary insight into the psychological consequences of quarantine and individual differences in coping with COVID-19 (Brooks et al., 2020). During the initial phase of the COVID-19 outbreak in China, more than half of the respondents rated the psychological impact of the outbreak as moderate-to-severe, and about one-third of those respondents reported feeling moderate-to-severe stress and anxiety (Wang et al., 2020). Gender, student status, and specific physical symptoms were associated with greater psychological impacts and higher levels of stress, anxiety, and depression (Wang et al., 2020). After controlling for demographic variables, further research showed that while perceived symptom severity was positively related to increased mental health symptoms, self-control was positively related to mental health symptoms (Li et al., 2020).

Furthermore, pandemics such as the COVID-19 pandemic or the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus pandemic (MERS-CoV) impose a significant risk of anxiety and stress on healthcare workers who are caring for infected patients, with one main concern being the risk of transmitting the infection to their families and/or acquiring it themselves (Temsah, et al., 2020).

To address coping with stress during a pandemic, religiosity and self-control were studied as resilience factors to COVID-19 stress in Singapore (Khoo, et al., 2021). Using a latent-variable approach, Singapore undergraduate students were examined and found religiosity predicted a heightened level of stress. The authors suggested the fear of COVID-19 transmission while engaging in religious activities as an explanation for this finding. Alternatively, this study demonstrated self-control was not associated with COVID-19 stress.

Another study, however, is inconsistent with the results achieved in the aforementioned studies (Mansdorf et al., 2020), in which the researchers measured the general psychological well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic for a random convenience sample of Jewish and Arab Muslim Israelis. The researchers demonstrated that these communities were relatively able to adapt and cope with the crisis, despite having experienced personal economic downturns and prolonged government-imposed social distancing restrictions. The study suggested the capacity for adapting developed through a national consciousness that gives substantial attention to coping with the stress of wars, terrorism, and threats.

Problem-Focused Coping and Emotion-Focused Coping

Coping refers to the process by which individuals “… can reduce the negative impact of stressful events on their emotional wellbeing” (Aldwin & Revenson, 1987, p. 345). Rather than being structural, fixed, or static, coping is perceived as a process that changes depending on the person and situation (Lazarus, 1993; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Therefore, many scholars pay attention to the various ways in which individuals cope with stress and how these various coping strategies are influenced by intrapersonal, interpersonal, and environmental factors. The focus is on moderating factors like coping strategy, personality traits, and/or social relations (Holahan & Moos, 1986). Monat and Lazarus define coping as an “individual’s efforts to master demands (conditions of harm, threat, or challenge) that are appraised (or perceived) as exceeding or taxing his or her resources” (Monat & Lazarus, 1991, p. 5). Therefore, this moderation depends primarily on each individual’s efforts, as observed by Monat and Lazarus.

This research has led to the understanding that individuals cope with stress by making active efforts to change the situation and/or change one’s emotional response to the situation, referred to as problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping, respectively (Lazarus, 1993). Problem-focused coping includes “employing active strategies to resolve the stressors,” whereas emotion-focused coping includes “processing and expressing feelings arising from the stressor” (Riley & Park, 2014, p. 588). Furthermore, problem-focused coping strategies include, but are restricted to, confrontative, interpersonal, and planful problem-solving. Comparatively, emotion-focused coping includes distancing, escape-avoidance, accepting responsibility, self-control, seeking social support, and positive reappraisal (Folkman & Lazarus, 1991).

Whether individuals employ problem-focused coping strategies, emotion-focused coping strategies, or a mixture of both, dealing with stress is subject to the situation and the individual’s appraisal of the stressful situation. As a result, it is widely observed that problem-focused coping is often employed when the individual perceives that the stressful situation can be controlled and, thus, able to be changed. Alternatively, emotion-focused coping is employed when the situation is perceived as uncontrollable and resistant to change (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984, 1984). Yet, some studies show problem-focused coping is more effective than emotion-focused coping, even in situations where the individual appraises the stressor as uncontrollable (Herman & Tetrick, 2009).

Initially, psychologists widely preferred problem-focused coping as it was only compared with the maladaptive forms of emotion-focused coping. Some emotion-focused coping efforts, however, are also thought to be necessary for problem-focused coping to be effective (Folkman, 1984). For instance, emotion-focused coping strategies like seeking social support and positive reappraisal can help individuals employ active problem-focused coping strategies such as planful problem-solving. Contrarily, some emotion-focused strategies, like self-distancing and escape-avoidance, may hinder the individual’s efforts to employ active problem-focused coping. Focusing on the ‘individual’s effort’ has nevertheless helped scholars examine coping, not only in terms of its adaptive success but also as a complex and fluid process whereby different coping strategies are viewed as equal.

One example is Baker and Berenbaum’s (2007) study, which identified an adaptive emotion-focused coping strategy termed “emotional-approach coping” (Baker & Berenbaum, 2007, p. 96). In this study, they argued that emotion-focused coping strategies are identified according to the particular form of emotion employed to cope with a particular situation. This study defined emotional-approach coping as a strategy that allows individuals to “engag[e] a particular problem in an active, dynamic way rather than avoid the problem in a passive, static way” (Baker & Berenbaum, 2007, p. 96). They found that individuals who were ambivalent and/or unclear about their emotions, less attentive to them, and/or had difficulty expressing them benefitted more from emotional-approach coping. Comparatively, individuals who were clear about their emotions, attentive to them, and did not have difficulty expressing them benefitted more from problem-focused coping.

Additionally, emotional-approach coping is more beneficial for individuals experiencing achievement stressors than individuals experiencing interpersonal stressors. This difference is because achievement stressors are usually associated with problem-focused coping, while interpersonal stressors are associated with emotion-focused coping. Further, emotional-approach coping requires socializing. Therefore, people who are more emotionally expressive can suffer from negative implications of excessive socializing, whereas people who are less emotionally expressive can benefit from practicing their ability to express their emotions to others (Baker & Berenbaum, 2007; Coyne et al., 1981). This difference shows how the employment of certain coping strategies not only depends on individual differences but also on the type of stressor or stressful situation.

This leads to the conclusion that coping is a situational process and the effectiveness of certain coping strategies depends on how well these strategies fit the context of stress (Park et al., 2004). The notion of “situational coping” has helped scholars move beyond the claim that certain coping strategies are more effective than others (Carver & Scheier, 1994, p. 185; Riley & Park, 2014). Moving beyond this dichotomy of effective problem-focused coping and maladaptive emotion-focused coping, scholars have offered new insights into the relationship between stressors, situations, coping strategies, and personality traits. These studies, which look at the relationship between coping strategies and different types of stressors, can be summed through the goodness of fit approach, which refers to how well an individual’s coping efforts are suitable for the specific situation (Conway & Terry, 1992; Park et al., 2004).

Therefore, the goodness-of-fit approach involves employing situationally appropriate coping strategies (Park et al., 2004). Consistent with the goodness of fit approach, Riley and Park (2014) introduced the concept of “meaning-focused coping” (Riley & Park, 2014, p. 589). Meaning-focused coping refers to the process of changing the appraised meaning of the stressor or stressful situation to match the individual’s goals. This coping strategy is also referred to as “positive reinterpretation coping,” and is perceived as especially helpful when individuals appraise stressors and/or stressful situations as uncontrollable (Linley & Joseph, 2004, p. 16; Park, 2010).

Riley and Park (2014) found that, in contrast to problem-focused coping, meaning-focused coping did not positively correlate with adjustment. They suggested that this was because meaning-focused coping serves as a precursor to problem-focused coping. As such, positive reinterpretation allows for active coping, which leads to positive adjustment. However, meaning-focused coping is also dependent on the type of stressor. Therefore, meaning-focused coping may be more helpful when dealing with interpersonal stressors, while problem-focused coping may be more helpful when dealing with achievement stressors. Overall, this supports the complex and particular interactions between examining the influences of both the individual and the situation on the effectiveness of coping strategies.

Coping Strategies and Self-Control

Self-control is widely considered an adaptive emotion-focused coping strategy (Folkman & Lazarus, 1991). Rosenbaum (1998) defines self-control as a system of goal-oriented cognitive skills that enable people to achieve their objectives, manage negative thoughts and emotions, delay gratification, and cope with stressful situations. Moreover, Rosenbaum (1990) makes a distinction between redressive self-control, which involves reactive coping, and reformative self-control, which involves active coping directed at changing one’s behaviour. According to Rosenbaum (1989), most scholars examining stress and coping are primarily focused on understanding redressive self-control and its relation to personality traits. Alternatively, behavioural approaches consider self-control as a coping strategy that is more affected by social-situational factors than fixed personality traits.

Nevertheless, many scholars agree that one’s ability to self-control as well as the perception of self-control (personal control) highly affects the individual’s mental and physical health and well-being. Therefore, people with higher self-control are perceived to have better mental and physical health outcomes than people with lower self-control (Bandura, 1997; Eizenman, Nesselroade, Featherman, & Rowe, 1997; Skinner, 1995).

Further, higher abilities to self-control and stronger perceptions of self-control lead to lesser emotional and physical reactivity to stressors (Agbaria & Bdier, 2019; Neupert et al., 2007). Meanwhile, lower self-control abilities and perceptions lead to greater emotional and physical reactivity to stressors. Higher self-control is also often associated with active coping strategies such as support-seeking and positive reappraisal (Sygit-Kowalkowska et al., 2015). Comparatively, low self-control is often associated with passive and maladaptive coping strategies such as helplessness and escape-avoidance.

Researchers assert that self-control, in addition to escape-avoidance and seeking support, are usually employed during the primary appraisal of the stressor and/or stressful situation (Folkman et al., 1986). Comparatively, they argue secondary appraisals demand the employment of a wider variety of coping strategies since individuals would have had more access to information and more time to think about the possible changeability of the situation. Nonetheless, self-control, in contrast to escape-avoidance, is thought to demand the employment of positive coping strategies, which lead to more positive outcomes. Boals, van Dellen, and Banks (2011) found that a higher ability to self-control was associated with adaptive coping strategies, such as seeking support, as well as better mental and physical health outcomes. Similarly, a lower ability to self-control was associated with maladaptive coping strategies, such as escape-avoidance coping, as well as worse mental and physical health outcomes.

However, Boals and colleagues (2011) found that self-control neither correlated significantly with problem-focused coping nor with emotion-focused coping. Therefore, we can hypothesize that self-control is an emotion-focused coping strategy that can act as a precursor to help achieve problem-focused coping. Self-control is especially employed when individuals experience achievement stressors, which usually demand the use of planful problem-solving (Rosenbaum, 1990; O'Brien & DeLongis, 1996). Therefore, self-control may also help achieve active problem-focused coping. This is consistent with findings that self-control was mostly employed when individuals dealt with achievement or work-related stressors (Folkman et al., 1986) and that achievement stressors usually evoked problem-focused coping (Baker & Berenbaum, 2007; Riley & Park, 2014).

Coping Strategies and Religiosity

Religiosity is considered by many scholars as an adaptive, emotion-focused coping strategy (McIntosh et al., 1993). In contrast to maladaptive and passive emotion-focused coping strategies, such as escape-avoidance and denial, religiosity is considered an adaptive and active coping strategy that functions similarly to seeking social support, positive reappraisal, and restraint coping (Carver & Scheier, 1994). In contrast, other scholars align religiosity with escape-avoidance and denial, thus perceiving religiosity as a passive and maladaptive emotion-focused coping strategy (see Pargament, 2002). This suggests a complex, multidimensional relationship between individuals and religious coping.

Prior research examined different personality traits and/or social conditions that influence whether individuals employ religious coping. Regarding the relationship between religiosity as a coping strategy and the Big Five personality traits, MCRae and Costa (1986) found that individuals classified as low on the Openness to Experience level were most likely to use religiosity as a coping strategy. Regarding social conditions, Koenig et al. (1988) found that the poorer and less educated groups in society employed religious coping as a means to support their mental health and well-being. However, more recent research has looked into different forms of religious coping and the effectiveness in certain social groups.

Hayward and Krause’s (2016) study examined the effectiveness of religious coping in a sample of mostly Christian adults in the USA. They found that religious commitment and attendance correlated with positive coping, while religious doubt correlated with negative coping. More importantly, they found that positive religious coping increased with age—as older adults employed less negative religious coping more often than younger adults. Gender and race also appeared to play a role in religious coping, as women, as well as African Americans, employed more positive religious coping than men or Whites (Hayward & Krause, 2016). Hence, the effectiveness of religious coping seems to be determined by the form of religion one is affiliated with, the culture in which this religious form is manifested, and each individual’s complex dimensions. Once again, this supports the nuance of examining both individual and situational factors when evaluating the effectiveness of coping strategies.

Positive religious coping appears to be especially important for long-term stressors (Pargament, 2002). Religious coping is effective when individuals are able to employ positive religious coping such as support-seeking and positive reappraisal (Simonic & Klobucar, 2017).

This is supported by other studies examining the effectiveness of religious coping for different individuals across various contexts. For instance, one study demonstrated that lower perceptions of pain among Muslim cancer patients in Iran were significantly related to positive religious coping (Goudarzian et al., 2018). This is in tandem with another study that found that religious coping increases the individual’s acceptance of unchangeable circumstances and tolerance towards perceived life hardships (Tehri-Kharameh et al., 2013). Nonetheless, it was also found that cancer patients who were experiencing anxiety and depression tended to employ negative religious coping more than positive religious coping (Ng et al., 2017). These studies show that if religious faith and participation are interpreted as searching for meaning, support-seeking, self-development, and self-control, then religiosity and participation become adaptive and active forms of coping.

The Present Study

This current study was the first to investigate the relationship of coping with stress due to the COVID-19 outbreak with self-control skills and religiosity among Israeli-Palestinian college students (n = 465). Adolescents living in Arab societies have unique challenges that may elevate the likelihood of exhibiting symptoms of stress during this crisis. However, this population has been understudied in this context. Furthermore, previous literature shows that self-control skills and religiosity have positively correlated with problem-focused coping. Thus, this current research sought to demonstrate the importance of these variables in countering stress resulting from the COVID-19 outbreak in a unique, non-Western society.

The Israeli-Palestinian minority living in Israel is of particular uniqueness. This community lives as a collective society that is experiencing rapid modernization along with "Israelization" (Al Hajj, 1996), while also experiencing movements in the opposite direction by Islamization and "Palestinianization" (Samoha, 2004). In addition to the formal and informal discrimination faced by many minorities, the Israeli-Palestinian community in Israel has to lead a double life as an undesirable ethnic, religious, and political minority living in a Jewish-majority state. Hence, when compared to the Jewish community living in Israel, the Israelis-Palestinian community exists on the fringes of Israeli society, being disadvantaged in terms of social and health services, lower economic status, and lower mental health welfare. Therefore, this population faces a unique dichotomy within their own culture that may cause challenges to their identity formation (Ericson, 1962; Sue and Sue, 2003). This context highly informs the relationship between individual characteristics and stress coping strategies.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Israeli-Palestinian minority was further marginalized in the public discourse when it did not meet the priority criteria for governmental health services. This led to the exclusion of the Israeli-Palestinian community from the general mass COVID-19 tests carried out by the government, as well as the narrative of public guidelines around the disease.

Youngmann and Kushnirovich (2021) studied the impact of depleted resources caused by COVID-19 on 1,197 respondents from both ethnic minorities and majority populations. They found that the Israelis-Palestinians were more concerned than the majority ethnicity about the potential loss of already depleted resources and that this concern had a greater impact on emotional well-being of Israeli-Palestinians than on the majority ethnic population. These findings make the empirical investigation of coping strategies and resources in this population even more pertinent. Thus, the current study examines the relationship of coping with stress with self-control skills and religiosity among the Israeli-Palestinian minority. Based on previous research findings, it was hypothesized that among Israeli-Palestinian college students in Israel (1) self-control skills and religiosity would be negatively associated with maladaptive, emotion-focused coping, and (2) self-control skills and religiosity would be positively associated with adaptive, problem-focused coping.

Methodology

Sample

The sample consisted of 465 Israeli-Palestinian college students, 79% of whom were females and 21% males. Participants’ ages ranged from 19 to 30 years (M = 26.18, SD = 5.18). The participants were recruited using non-random convenience sampling from eight colleges in Israel. Approximately 62% of the participants grew up in villages (rural) and 38% grew up in cities (urban). In terms of religious affiliation, 80% of the participants identified as Muslims, 16% identified as Christians, and 4% identified as Druze.

Participant demographic characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|

Variable | N | Percentage |

Age | ||

19–30 | 465 | 100 |

Gender | ||

Female | 367 | 79 |

Male | 98 | 21 |

Residence | ||

Rural | 288 | 62 |

Urban | 177 | 38 |

Religion | ||

Muslim | 372 | 80 |

Christian | 74 | 16 |

Druze | 19 | 4 |

Measures

Each measure was translated from English to Arabic by five interdisciplinary Israeli-Palestinian scholars. The measures were assessed by the researchers, in collaboration with the five experts, and they were checked for the clarity and cultural appropriateness of both content and translation. The questionnaires were then translated back into English by an independent translation expert. Finally, the questionnaire was distributed to all 465 students and had a response rate of 86%.

Demographic Variables Questionnaire

The variables included in this instrument were self-reported gender, age, residence, and religion.

Coping Style Questionnaire

This questionnaire is based on Carver, Scheier and Weintruab’s (1989) questionnaire that was first translated into Hebrew (Ben-Zur, 2005), and then translated into Arabic (Odeh, 2014). The Arabic and Hebrew versions include 30 items assessed according to a scale of 1 (not at all) to 5 (to a great extent). These items contain variables classified according to problem-focused coping (α = 0.73) and emotion-focused coping (α = 0.70).

Self-Control Questionnaire

This questionnaire was developed by Rosenbaum (1980) and asks individuals to self-report on their usage of cognitive (e.g. self-talk) and behavioural (e.g. problem-solving) strategies for coping with emotional and physiological stressors. The measure was adapted to be suitable for children and adolescents by Rosenbaum and Ronen (1990). This 32-item version asks individuals to report on numerous cognitive (e.g. self-talk) and behavioural (e.g. delaying gratification) skills, similar to the version for adult populations. Each question is rated on a Likert scale from 1 (very untypical of me) to 6 (very typical of me). Example questions include “When I am in a bad mood I try to think of good things that can make me happy or things that gave me pleasure in the past” and “When I don't know the answer to a question in a test I go on to the next question and try not to let the unanswered question bother me” (Hamama, 1996).

The Arabic version of the scale demonstrated good internal consistency in a previous study among Israeli-Palestinian adolescents (Agbaria & Daher, 2015) (α = 0.84). This good internal consistency was replicated in the current study (α = 0.81), and all the items had a factor load greater than 0.4.

Positions Regarding Religion Questionnaire

This questionnaire was developed by Kendler and colleagues (2003). The questionnaire includes 63 items measuring five attitudes towards religion: religiosity in general, social religiosity, forgiveness, God as judge, and lack of desire for revenge. Each participant evaluates each of the items on a five-point scale (1 = never to 5 = always). The present research only made use of the first section, the religiosity dimension. This section included 31 items reflecting elements of religiosity, including spirituality and understanding of one's place in the universe, and how participants’ relationship with God is expressed in their daily activities and during crises. Moreover, the questionnaire was translated into Arabic and adapted to fit the Arab population: four items were deleted from the questionnaire and 12 items were added. Example questions were: "I live my life as God commands” and "I look for opportunities to strengthen my spirituality on a daily basis.” Cronbach's alpha values for the various sections were high, ranging from α = 0.86 to α = 0.93 (Agbaria, 2014). In the present study, Cronbach Alpha was (α = 0.88). All the items had a factor load greater than 0.4.

Research Procedure

The study sample was recruited using non-random convenience sampling and was open to all attendees of eight colleges in Israel. The research was conducted in 2020 during the first three months of the COVID-19 outbreak in Israel. After obtaining the needed clearances from each of the colleges as well as the ethical committee (trial protocol 1320) at the lead researcher’s college, all participants gave informed consent to participate in the study and for the results to be published anonymously for scientific purposes. The questionnaires were distributed using Google forms and stressed that the questionnaires would remain anonymous. Approximately 80% of the students included in the convenience sampling agreed to participate, resulting in a sample size of 465 individuals.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics for the study variables (problem-focused coping, emotion-focused coping, self-control, and religiosity) were examined. Assumptions of normality, homogeneity of variances, linearity and independence were confirmed to demonstrate the appropriateness of parametric testing. In order to examine the study hypotheses, two approaches were used.

First, bivariate correlations were examined for all study variables. Correlations were considered to have a small effect size if r =|.10−0.29|, medium if r =|.30−0.49|, and large if r =|.50−0.1.00|. Second, stepwise linear multiple regression models were employed to test the associations of self-control and religiosity with employing problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping. The multiple regression model was used to understand how each of the individual characteristics (self-control and religiosity) uniquely relates to the outcomes of coping with stressors using problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping, while also controlling for other independent variables in the model, and control demographic variables (gender, age, residence, and religious group identification).

Results

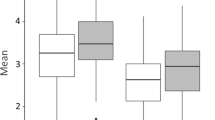

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of the study variables. Overall, the students exhibited medium scores in the coping styles questionnaire as well as medium scores in each of self-control and religiosity questionnaires.

Table 2 reveals the correlations between the study variables.

Consistent with the first study hypothesis, there was a significant negative correlation between emotion-focused coping and self-control (r = −0.32, p < 0.01) as well as emotion-focused coping and religiosity (r = −0.36, p < 0.01).

The regression model (Table 3) found that self-control explains the significant amount of variance in emotion-focused coping scores (β = −0.21, p < 0.01), as did religiosity (β = −0.17, p < 0.01).

Consistent with the second study hypothesis, there was a significant positive correlation between problem-focused coping and self-control (r = 0.40, p < 0.01) as well as problem-focused coping and religiosity (r = 0.30, p < 0.01).

The regression model (Table 4) found that self-control also explains the significant amount of variance in problem-focused coping scores (β = 0.19, p < 0.01), as did religiosity (β = 0.16, p < 0.01).

Discussion

The present study aimed to elucidate the individual characteristics that may assist Israeli-Palestinian college students cope with the stressors associated with the COVID-19 pandemic by examining the relationship of coping with stress with self-control skills and religiosity among Israeli-Palestinian college students.

Self-Control Skills and Coping Strategies

The study results indicate that self-control skills positively correlated with adaptive, problem-focused coping and negatively correlated with maladaptive, emotion-focused coping. These findings align with the previous studies that were conducted in similar situations (Agbaria & Bdier, 2019; Agbaria & Natur, 2018; Mansdorf, Weinberg, Weinberg &, Mahajnah, 2020). Thus, the present findings expand upon prior research to support that high self-control is associated with active coping strategies such as problem-focused coping, while low self-control is associated with passive and maladaptive forms of emotion-focused coping (Boals, van Dellen, & Banks, 2011; Sygit-Kowalkowska et al., 2015).

Further, self-control as an adaptive emotion-focused coping strategy can act as a precursor to help achieve problem-focused coping. Self-control is specifically employed when individuals are experiencing achievement stressors (Rosenbaum, 1990), which usually demand the use of planful problem-solving (O'Brien & DeLongis, 1996). Therefore, self-control can also help achieve active problem-focused coping. This aligns with the findings that self-control may be mostly employed when individuals are dealing with achievement, or work-related, stressors (Folkman et al., 1986), and that achievement stressors usually evoke problem-focused coping (Baker & Berenbaum, 2007; Riley & Park, 2014).

Examining the way self-control skills are implemented may explain these results. Individuals with these skills are able to divert attention and think creatively to find alternative solutions, change the automatic ways of thinking and replace those processes with planned and more appropriate ways of thinking, use self-talk and self-restraint, and resist overreacting in difficult and stressful situations. Self-control skills can thus lead to balanced thinking and carefully planned responses, which are necessary for problem-focused coping (Agbaria & Bdier, 2019).

Religiosity and Coping Strategies

Religiosity positively correlated with problem-focused coping and negatively correlated with emotion-focused coping. These findings also align with the previous studies conducted in similar situations. For example, Hayward and Krause’s (2016) study found that religious commitment and attendance correlated with positive, problem-focused coping while religious doubt correlated with negative, emotion-focused coping. Additionally, these findings align with previous studies that emphasize the importance of religiosity, religious faith, and religious participation as protective factors that contribute to more resilience and greater ability to cope with stressful events (Abu-Hilal et al., 2017; Agbaria, 2019; Agbaria & Bdier, 2019; Agbaria, Mahamid, & ZiyaBerte, 2017; Agbaria & Natur, 2018; Nouman & Benyamini, 2019).

Religiosity becomes an adaptive and active form of coping when religious faith and participation are considered in the context of searching for meaning, support-seeking, self-development, and self-control. Therefore, religious coping is effective when individuals are able to employ positive religious coping, such as support-seeking and positive reappraisal, in contrast to the maladaptive forms of religious coping, such as fear and guilt (Simonic & Klobucar, 2017). One possible explanation for these findings is that religiosity may protect against stress-oriented behaviours such that persons with high religiosity may have different cognitions based on their religious values that inform their behaviour in a manner that discourages maladaptive behaviours in stressful conditions (Agbaria & Wattad, 2011).

Study Limitations

The results of the present study should be interpreted in the light of three limitations. First, the sample was not recruited using a randomized subset of the larger population, and all participants identified as one racial group. Future research may consider recruiting a more diverse sample to permit direct comparisons across racial and other religious groups as a means to increase the validity of the current findings. Second, the data was comprised only of self-report questionnaires, which may be subject to reporting bias. This may be especially high among college students who may be more likely to either conform to or rebel against social norms. Lastly, the present study did not assess whether individuals were enrolled in mental health treatment during this period. It may also be important to assess whether the present associations may be mediated by whether individuals were enrolled in mental health treatment during this stressful time. Thus, further studies may consider additional tools of measurement (e.g. behavioural observations). Finally, there is a need for future research to examine the relationships of coping with stress with self-control skills and religiosity by testing a wider variety of moderating and mediating effects.

Conclusions

The present study was the first to investigate the relationship of coping with stress due to the COVID-19 outbreak with self-control skills and religiosity among Israeli-Palestinian college students. The study aimed to examine how self-control skills and religiosity may increase one’s adaptive coping during the COVID-19 pandemic. The results showed that self-control increased one’s ability to cope actively, adaptively, and efficiently. In addition, the results demonstrated that religious students tended to employ active and adaptive coping. Therefore, the results of the present study align with results from other studies, which indicate that self-control skills and religiosity positively correlate with active problem-focused coping. Lastly, this research may provide insight into coping with stress in a manner that may increase early identification and intervention efforts of negative psychiatric manifestations.

References

Abu-Hilal, M., Al-Bahrani, M., & Al-Zedjali, M. (2017). Can religiosity boost meaning in life and suppress stress for Muslim college students? Mental Health, Religion and Culture, 20(3), 203–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2017.1324835

Agbaria, Q. (2019). Predictors of personal and social adjustment among Israeli-Palestinian teenagers. Child Indicators Research, pp. 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.96.2.195.

Agbaria, Q., & Bdier, D. (2019). The role of self-control, social support and (positive and negative affects) in reducing test anxiety among Arab teenagers in Israel. Child Indicators Research, 13, 1023–1041. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-019-09669-9

Agbaria, Q., Mahamid, F., & ZiyaBerte, D. (2017). Social support, self-control, religiousness and engagement in high risk-rs among adolescents. The International Journal of Indian Psychology, 4, 13–33. https://doi.org/10.25215/0404.142.

Agbaria, Q., & Mokh, A. A. (2021). Coping with stress during the coronavirus outbreak: The contribution of big five personality traits and social support. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-021-00486-2

Agbaria, Q., & Abu-Mokh, A. J. (2022). The use of religious and personal resources in coping with stress during COVID-19 for Palestinians. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02669-5

Agbaria, Q., & Natur, N. (2018). The relationship between violence in the family and adolescents aggression: The mediator role of self-control, social support, religiosity, and well-being. Children and Youth Services Review, 91, 447–456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.06.016

Agbaria, Q., & Wattad, N. (2011, July 25–26). Self-control and religiosity as related to subjective well-being among Arab students [Conference Presentation]. Third International conference Opening Gates in Teacher Education.

Aldwin, C. M., & Revenson, T. A. (1987). Does coping help? A reexamination of the relation between coping and mental health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(2), 337–348. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.53.2.337

Baker, J. P., & Berenbaum, H. (2007). Emotional approach and problem-focused coping: A comparison of potentially adaptive strategies. Cognition and Emotion, 21(1), 95–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930600562276

Boals, A., Vandellen, M. R., & Banks, J. B. (2011). The relationship between self-control and health: The mediating effect of avoidant coping. Psychology and Health, 26(8), 1049–1062. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2010.529139

Brooks, S., Webster, R., Smith, L., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., & Rubin, G. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet, 395(10227), 912–920. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8

Byrd, D. R., & McKinney, K. J. (2012). Individual, interpersonal, and institutional level factors associated with the mental health of college students. Journal of American College Health, 60(3), 185–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2011.584334

Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (1994). Situational coping and coping dispositions in a stressful transaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66(1), 184–195. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.66.1.184

Conway, V. J., & Terry, D. J. (1992). Appraised controllability as a moderator of the effectiveness of different coping strategies: A test of the goodness-of-fit hypothesis. Australian Journal of Psychology, 44(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049539208260155

Coyne, J. C., Aldwin, C., & Lazarus, R. S. (1981). Depression and coping in stressful episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 90(5), 439–447. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.90.5.439

Dubey, S., Biswas, P., Ghosh, R., Chatterjee, S., Dubey, M. J., Chatterjee, S., Lahiri, D., & Lavie, C. J. (2020). Psychosocial impact of COVID-19. Diabetes and Metabolic Syndrome, 14(5), 779–788. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2020.05.035

Folkman, S. (1984). Personal control and stress and coping processes: A theoretical analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46(4), 839–852. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.46.4.839

Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Coping and emotion. In A. Monat & R. S. Lazarus (Eds.), Stress and coping: An anthology (pp. 207–227). Columbia University Press.

Folkman, S., Lazarus, R. S., Dunkel-Schetter, C., DeLongis, A., & Gruen, R. (1986). Dynamics of a stressful encounter: Cognitive appraisal, coping, and encounter outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50(5), 992–1003. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.50.5.992

Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1985). If it changes it must be a process: Study of emotion and coping during the three stages of a college examination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48(1), 150–170. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.48.1.150

Gao, J., Zheng, P., Jia, Y., Chen, H., Mao, Y., Chen, S., et al. (2020). Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS ONE, 15(4), e0231924. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231924

Goudarzian, A. H., Jafari, A., Beik, S., & Nesami, B. M. (2018). Are religious coping and pain perception related together? Assessment in Iranian cancer patients. Journal of Religion and Health, 57, 2108–2117. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-017-0471-4

Harris, J. I., Erbes, C. R., Engdahl, B. E., Ogden, H., Olson, R. H. A., Winskowski, A. M. M., Campion, K., & Mataas, S. (2012). Religious distress and coping with stressful life events: A longitudinal study. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 68(12), 1276–1286. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.21900

Hayward, R. D., & Krause, N. (2016). Classes of individual growth trajectories of religious coping in older adulthood: Patterns and predictors. Research on Aging, 38(5), 554–579. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027515593347

Heiat, M., Heiat, F., Halaji, M., Ranjbar, R., Tavangar Marvasti, Z., Yaali-Jahromi, E., Azizi, M. M., Morteza Hosseini, S., & Badri, T. (2021). Phobia and Fear of COVID-19: Origins, complications and management, a narrative review. Annali Di IGiene : Medicina PReventiva e Di COmunita, 33(4), 360–370. https://doi.org/10.7416/ai.2021.2446

Herman, J. L., & Tetrick, L. E. (2009). Problem-focused versus emotion-focused coping strategies and repatriation adjustment. Human Resource Management, 48(1), 69–88. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20267

Holahan, D. H., & Moos, R. H. (1986). Personality, coping, and family resources in stress resistance: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(2), 389–395. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.2.389

Kendler, K. S., Liu, X.-Q., Gardner, C. O., McCullough, M. E., Larson, D., & Prescott, C. A. (2003). Dimensions of religiosity and their relationship to lifetime psychiatric and substance use disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(3), 496–503. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.160.3.496

Khoo, S. S., Toh, W. X., & Yang, H. (2021). Seeking control during uncontrollable times: Control abilities and religiosity predict stress during COVID-19. Personality and Individual Differences, 175, 110675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.110675

Koenig, H. G., George, L. K., & Siegler, I. C. (1988). The use of religion and other emotion-regulating coping strategies among older adults. The Gerontologist, 28(3), 303–310. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/28.3.303

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. Springer Publishing Company.

Lazarus, R. S. (1990). Theory-based stress measurement. Psychological Inquiry, 1(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli0101_1

Lazarus, R. S. (1993). Coping theory and research: Past, present, and future. Psychosomatic Medicine, 55(3), 234–247. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-199305000-00002

Li, J. B., Yang, A., Dou, K., & Cheung, R. (2020). Self-Control Moderates the association between perceived severity of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and mental health problems among the chinese public. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(13), 4820. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134820

Linley, P. A., & Joseph, S. (2004). Positive change following trauma and adversity: A review. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 17(1), 11–21. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOTS.0000014671.27856.7e

Mahamid, F. A., & Bdier, D. (2021). The association between positive religious coping, perceived stress, and depressive symptoms during the spread of coronavirus (COVID-19) among a sample of adults in Palestine: A cross sectional study. Journal of Religion and Health, 60, 34–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-01121-5

Mansdorf, I. J., Weinberg, M., Weinberg, J., & Mahajnah, M. (2020, May 18). Resilience, stringency of restrictions and psychological consequences of COVID-19 in Israel: Comparing Jewish and Arab samples. Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs. https://jcpa.org/article/resilience-stringency-of-irestrictions-and-psychological-consequences-of-covid-19-in-israel/.

McIntosh, D. N., Silver, R. C., & Wortman, C. B. (1993). Religion’s role in adjustment to a negative life event: Coping with the loss of a child. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(4), 812–821. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.65.4.812

McRae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (1986). Personality, coping and coping effectiveness in an adult sample. Journal of Personality, 54(2), 385–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1986.tb00401.x

Monat, A., & Lazarus, R. S. (eds). (1991). Stress and coping: An anthology. Columbia University Press.

Neupert, S. D., Almeida, D. M., & Charles, S. T. (2007). Age differences in reactivity to daily stressors: The role of personal control. The Journal of Gerontology, 62(4), 216–225. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/62.4.P216

Ng, G. C., Mohamed, S., Sulaiman, A. H., & Zainal, N. Z. (2017). Anxiety and depression in cancer patients: The association with religiosity and religious coping. Journal of Religion and Health, 56, 575–590. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-016-0267-y

Nouman, H., & Benyamini, Y. (2019). Religious women’s coping with infertility: Do culturally adapted religious coping strategies contribute to well-being and health? International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 26(2), 154–164. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-018-9757-5

O’Brien, T., & DeLongis, A. (1996). The interactional context of problem-emotion-, and relationship-focused coping: The role of the big five personality factors. Journal of Personality, 64(4), 775–813. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00944.x

Pargament, K. (2002). God help me: Advances in the psychology of religion and coping. Archiv Für Religionspsychologie / Archive for the Psychology of Religion, 24, 48–63. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23912399

Park, C. L. (2010) Making sense of the meaning literature: An integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events. Psychological Bulletin, 136(2), 257–301. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018301

Park, C. L., Armeli, S., & Tennen, H. (2004). Appraisal-coping goodness of fit: A daily internet study. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(5), 558–569. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167203262855

Riley, K. E., & Park, C. L. (2014). Problem-focused coping vs. meaning-focused coping as mediators of the appraisal-adjustment relationship in chronic stressors. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 33(7), 587–611. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2014.33.7.587

Rosenbaum, M. (ed). (1990). Learned Resourcefulness - On coping skills, self-control and adaptive behaviour. Springer Publishing Company.

Rosenbaum, M. (1989). Self-control under stress: The role of learned resourcefulness. Advances in Behaviour Research and Therapy, 11(4), 249–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/0146-6402(89)90028-3

Simonič, B., & Klobučar, N. R. (2017). Experiencing positive religious coping in the process of divorce: A qualitative study. Journal of Religion and Health, 56, 1644–1654. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-016-0230-y

Sygit-Kowalkowska, E., Weber-Rajek, M., Porażyński, K., Goch, A., Kraszkiewicz, K., & Bułatowicz, I. (2015). Emotional self-control, coping with stress and psycho-physical well-being of prison officers. Medycyna Pracy, 66(3), 373–382. https://doi.org/10.13075/mp.5893.00182

Taheri-Kharameh, Z., Saeid, Y., & Ebadi, A. (2013). The relationship between religious coping styles and quality of life in patients with coronary artery disease. Iranian Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 2(1), 24–32. http://journal.icns.org.ir/article-1-147-en.html

Temsah, M. H., Al-Sohime, F., Alamro, N., Al-Eyadhy, A., Al-Hasan, K., Jamal, A., & Somily, A. M. (2020). The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on health care workers in a MERS-CoV endemic country. Journal of Infection and Public Health, 13(6), 877–882. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2020.05.021

Wang, C., Pan, R., Wan, X., Tan, Y., Xu, L., McIntyre, R. S., Choo, F. N., Tran, B., Ho, R., Sharma, V. K., & Ho, C. (2020). A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 87, 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.028

Youngmann, R., & Kushnirovich, N. (2021). Resource threat versus resource loss and emotional well-being of ethnic minorities during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(23), 12590. MDPI AG. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312590.

Funding

The authors have not disclosed any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Author declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee (include name of committee + reference number) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Agbaria, Q., Mokh, A.A. Coping with Stress During the COVID-19 Outbreak: The Contribution of Self-Control Skills and Religiosity in Arab Israeli-Palestinian Students in Israel. J Relig Health 62, 720–738 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-022-01686-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-022-01686-3