Abstract

Academic stress is the most common mental state that medical students experience during their training period. To assess academic stress, to find out its determinants, to assess other sources of stress and to explore the various coping styles against academic stress adopted by students. Methods: It was a cross sectional study done among medical students from first to fourth year. Standard self-administered questionnaires were used to assess academic stress and coping behaviour. Mean age of the 400 participants was 20.3 ± 1.5 years. 166(41.5%) of them were males. The academic stress was found to be of mild, moderate and severe level among 68(17%), 309(77.3%) and 23(5.7%) participants respectively. Overall coping with stress was found to be poor, average and good among 15(3.8%), 380(95%) and 5(1.2%) participants respectively. Passive emotional (p = 0.054) and passive problem (p = 0.001) coping behaviours were significantly better among males. Active problem coping behaviour (p = 0.007) was significantly better among females. Active emotional coping behaviour did not vary significantly between genders (p = 0.54). Majority of the students preferred sharing their personal problems with parents 211(52.7%) followed by friends 202(50.5%). Binary logistic regression analysis found worrying about future (p = 0.023) and poor self-esteem (p = 0.026) to be independently associated with academic stress. Academic stress although a common finding among students, the coping style to deal with it, was good only in a few. The coping behaviours were not satisfactory particularly among male participants. This along with other determinants of academic stress identified in this study need to be addressed during counselling sessions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Academic stress has been reported to be the most common mental state that medical students experience during their training period (Ramli et al. 2018). It is on the rise among them probably due to increasing course requirements (Ramli et al. 2018; Drolet and Rodgers 2010). Kumaraswamy (2013) observed that the issues known to precipitate academic stress were excessive assignments, peer competition, examinations and problems related to time management. University students, for the life phase they are going through, also have to deal with many other stresses such as detachment from the family, building of self-identity and issues concerning adolescence period and those in relation to student-workers. The stress of the medical student is also connected to the relationship with the patient in the clinical period.

Some amount of academic stress is beneficial as it brings about healthy competition with peer group, promotes learning and helps to excel in academics (Malathi and Damodaran 1999; Afolayan et al. 2013). Lumley and Provenzano (2003) however reported that, excess of academic stress adversely affects academic performance, class attendance and psychological well-being of students. If it is not identified early and managed, it can cause depression, anxiety, behavioural problems, irritability, social withdrawal and physical illnesses (Adiele et al. 2018; Deb et al. 2015; Verma et al. 2002; Chen et al. 2013).

In addition to assessment of academic stress among under graduate medical students, it is also essential to analyze the various stress coping mechanisms adopted by them. This will help researchers in suggesting appropriate intervention strategies for the benefit of the students. Students in turn can educate their patients in future to identify stress and suggest measures to deal with it.

Previous studies have reported that medical students used active coping mechanisms (Al-Dubai et al. 2011; Chawla and Sachdeva 2018; Gade et al. 2014; Abouammoh et al. 2020), positive reframing (Al-Dubai et al. 2011; Chawla and Sachdeva 2018), planning (Chawla and Sachdeva 2018; Wu et al. 2018), positive reappraisal (Wu et al. 2018), emotional support (Chawla and Sachdeva 2018; Gade et al. 2014), peer discussions (Oku et al. 2015) and acceptance (Al-Dubai et al. 2011; Chawla and Sachdeva 2018) as means for coping stress. There were minimal reports of usage of avoidance strategies for coping stress among medical students (Al-Dubai et al. 2011; Chawla and Sachdeva 2018).

Royal College of Psychiatrists (2011) reported that students with secure attachments to family and those residing in a supportive community are in a better position to handle stress. Therefore assessment of various determinants of academic stress is essential to frame most suitable remedial measures for the benefit of the affected. This study was hence done to assess academic stress, to find out its determinants, to assess other sources of stress and to explore the various coping styles adopted by medical students to deal with academic stress in a coastal city in south India.

Materials and Methods

This cross sectional study was conducted in the month of March 2018 at a private medical college in Mangalore. The institutional ethics committee approval was taken before the commencement of the study. Permission to conduct the study was taken from the Dean. Sample size of 364 participants was calculated at 95% confidence intervals (CI), 90% power and the proportion of medical students with average level of academic stress taken as 51.4% based on the findings of Mostafavian et al. (2018). A non-response rate of 10% was added to arrive at the final sample size which was calculated as 400 participants. A total of 100 students of Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery course from first year to fourth year were therefore chosen to participate in this study using simple random sampling method.

The students were briefed about academic stress and the objectives of this study, in the classroom setting, and written informed consent was taken for their participation. In order to maintain anonymity, the filled in consent form were first collected back from the participants. Later the questionnaires were distributed by the investigators. It was a semi-structured questionnaire containing both closed and open ended questions. It was pre-tested in a group of ten students before its use in the current study. No changes in the questionnaire resulted following the pre-testing and the data collected in this phase were not included in the final study.

Data Collection Tools

Academic stress was assessed using the academic stress inventory tool for university students prepared by Lin and Chen (2009). They had reported the alpha value of Cronbach’s reliability test for this questionnaire as 0.90. The questionnaire was slightly modified during the content validation phase in this study to incorporate questions on career related issues along with few other minor changes. This questionnaire contained 35 items which were designed in a five point Likert scale. The responses in the scale were “completely disagree,” “disagree,” “neutral,” “agree,” and “completely agree”, with scores ranging from one to five points respectively. Cumulative scores ranging from 35 to 81, 82 to 128 and 129 to 175 were considered as mild, moderate and severe levels of academic stress respectively.

The coping techniques employed by the respondents was assessed using the academic stress coping style inventory developed by Lin and Chen (2010). The Cronbach’s alpha value of internal consistency for the stress coping style questionnaires was reported by them to be 0.83. It was shortened during the content validation phase to result in 25 questions designed again in Likert’s five-point scale. Scores were ranging from 5 for “completely agree” to 1 for “completely disagree”. Overall coping with stress was rated as poorly adoptive when cumulative score of the participant ranged from 25 to 58, average when it was 59 to 92 and good when it was 93 to 125.

Coping behaviour were grouped as active emotional coping, active problem coping, passive emotional coping and passive problem coping behaviours. Active emotional coping behaviour involved individuals adopting the attitude of emotional adjustment like positive thinking emotions and self-encouragement, when faced with academic stress. Active problem coping behaviour involved dealing academic stress by focussing at the centre of the problem and finding a solution themselves by being calm and optimistic or by searching assistance from external sources. Passive emotional coping behaviour involved constraining emotions, self-accusation, getting angry, blaming others or God or by giving up. Passive problem coping behaviour involved procrastinations, evasive behaviours or going into alcohol or drug abuse while facing academic stress (Lin and Chen 2010).

The overall alpha value of Cronbach’s reliability test for the academic stress and coping style inventory questionnaire used in this study was calculated to be 0.901, indicating excellent reliability.

Statistical Analysis

The data entry and analysis were done using IBM SPSS for Windows version 25.0, Armonk, New York. Statistical tests like Chi square test, Fisher’s exact test, Student’s unpaired t test and Karl Pearson’s coefficient of correlation were used for analysis. All the determinants of academic stress significant at 0.15 level were placed in the multivariable model. Backward stepwise elimination procedure was done to identify the independent determinants of academic stress in the model at the last step. p value 0.05 or less was used as the criterion for significance.

Results

A total of 400 students participated in this study and all of them gave satisfactorily filled forms. Their mean age was 20.3 ± 1.5 years and median age was 20 years with an Inter Quartile Range (19, 22) years. As many as 166(41.5%) of them were males. Out of the total participants, 45(11.2%) were local residents, 51(12.8%) were outsiders but within the same state, 262(65.5%) were from other states within India, 35(8.8%) were non-residential Indians and the rest 7(1.7%) were foreigners. Medium of schooling among 388(97%) students was English.

Among the participants, 67(16.7%) were currently staying at their home or rented apartment while the rest 333(83.3%) were staying in the hostels or were staying as paying guests. Majority of them [228(57%)] were staying with their friends. Among others, 118(29.5%) were staying alone, 46(11.5%) with their parents, 7(1.8%) with their relatives and one with her elder sibling.

With respect to lifestyle habits, majority of the participants [249(62.2%)] went to college by walk, and majority [339(84.7%)] slept for 6 to 8 h on an average per day. (Table 1).

Sources of Stress among Participants

Majority of students either agreed or strongly agreed that some teachers provided so much of academic information, making it difficult for students to assimilate knowledge [177(44.2%)]. Fear of failure in the exams was the other major cause of academic stress [206(51.5%)]. (Table 2).

Majority of students either agreed or strongly agreed that by missing few lectures, they felt anxious about falling short of attendance towards the end [204(51%)]. They also regretted having wasted time set apart for studies [240(60%)]. (Table 3).

Overall the level of academic stress was found to be mild among 68(17%), moderate among 309(77.3%) and severe among 23(5.7%) participants. The mean academic stress score was found to be 100.6 ± 19.7. Gender wise variation in academic stress levels was noticed. It was of mild, moderate and severe level among 29(17.5%), 129(77.7%) and 8(4.8%) males and among 39(16.7%), 180(76.9%) and 15(6.4%) females respectively (X2 = 0.472, p = 0.79).

The other non-academic sources of stress reported by participants were lack of sufficient vacations [130(32.5%)], staying away from family [103(25.7%)], worrying about future [70(17.5%)], low self-esteem [52(13%)], having trouble with friends 39(9.7%)], facing financial difficulties [33(8.2%)], interpersonal conflicts [28(16.7%)], conflicts with roommates [26(6.5%)], issues with partners [23(5.8%)], sleeping disorders [21(5.2%)], transportation problems [20(5%)], problems in the family [18(4.5%)], searching a partner [17(4.2%)] and lack of parental support [5(1.2%)].

14(3.5%) participants had underlying chronic morbidities. These morbidities were allergic rhinitis among 3, migraine among 3, polycystic ovarian disease among 3, menorrhagia among 2 and allergy, peptic ulcer, hypothyroidism, and impaired glucose tolerance in one student each.

Coping Strategies Adopted by Participants

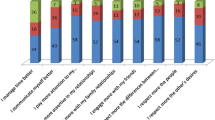

Majority of the participants [294(73.5%)] either agreed or strongly agreed that they tried to think or do something, that would make them feel happier and relaxed when they were stressed. (Table 4).

Overall coping with stress was found to be poor among 15(3.8%), average among 380(95%) and good among 5(1.2%) participants.

The mean coping with stress score was 75.2 ± 9.2. The mean score of various coping behaviours like active emotional coping (items 1 to 6), active problem coping (items 14 to 18), passive emotional coping (items 7 to 13) and passive problem coping (items 19 to 25) were found to be 21.7 ± 3.4, 13.2 ± 2.7, 18.6 ± 4.6 and 18.3 ± 4.2 respectively. (Table 4).

Mean active emotional coping score among males (n = 166) was 21.5 ± 3.5 and among females (n = 234) was 21.8 ± 3.3 (t = 0.613, p = 0.54). Mean passive emotional coping score among males (n = 166) was 19.1 ± 5.0 and among females (n = 234) was 18.2 ± 4.1 (t = 1.933, p = 0.054). Mean active problem coping score among males (n = 166) was 12.8 ± 2.8 and among females (n = 234) was 13.5 ± 2.5 (t = 2.711, p = 0.007). Mean passive problem coping score among males (n = 166) was 19.1 ± 4.4 and among females (n = 234) was 17.7 ± 3.9 (t = 3.412, p = 0.001).

The various measures adopted by participants to deal with stress were sharing problems with others [223(56.2%)], meditation [132(56.8%)], performing yoga [50(12.8%)], sleeping [29(7.5%)], practicing Tai Chi [13(3.5%)] and listening to music [11(3%)]. Other methods like watching television and exercising were reported by 8(2.2%) participants each, aromatherapy and sports by 5(1.3%) each, eating favourite food and consuming alcohol by two each and browsing through the internet by one participant.

Majority of the students preferred sharing their personal problems with parents 211(52.7%), followed by friends 202(50.5%), siblings 71(17.7%) and others 26(6.5%).

Eight(2%) participants reported using medications for the management of stress. One of them had taken Lorazepam tablets while another Sertraline tablets. The rest of them did not specify the medications.

Reasons like lack of sufficient vacations and worrying about future were found to have highly significant association with academic stress among participants (p ≤ 0.001). (Table 5).

Coping with stress was average/good among 328(98.8%) participants with moderate/severe levels of academic stress in comparison to 57(83.8%) with mild level of academic stress (p < 0.00001).

Similarly correlation of academic stress scores with stress coping scores was found to be significant (r = 0.467, p < 0.001). Also correlation between academic stress scores with passive emotional (r = 0.513, p < 0.001) and passive problem (r = 0.401, p < 0.001) coping behaviours were found to be significant. However academic stress was not significantly correlated with active emotional (r = − 0.036, p = 0.468) and active problem (r = 0.072, p = 0.149) coping behaviours.

Binary logistic regression analysis found worrying about future (p = 0.023) and poor self-esteem (p = 0.026) among participants to be significantly associated with academic stress after adjusting the confounding effect of other variables in the model. (Table 6).

For calculating unadjusted Odds Ratio and 95% CI, participants staying with friends/alone were compared with those staying with parents/siblings/relatives (reference value), participants reporting speed of internet connection at place of stay as average/poor were compared with those reporting good connectivity (reference value).

Discussion

An interesting fact about this study was that the response rate was total. This supports the importance of this study which addresses a felt need of every medical student.

Academic stress of moderate to severe level were reported among 83% participants in this study. In other studies done among medical students, academic stress was reported among 50% (Dyrbye et al. 2008), 53% (Bamuhair et al. 2015), 61% (Zamroni et al. 2018) and 74.6% (Mostafavian et al. 2018) participants. Academic stress among university students of other courses were reported among 48.8% (Reddy et al. 2018), 70.7% (Sharififard et al. 2014) and 73% (Adiele et al. 2018) participants. From these comparisons, it was obvious that academic stress was high among the participants in this study probably because of cultural factors.

There was no association between academic stress and gender of participants in this study as also reported by Mostafavian et al. (2018) and Zamroni et al. (2018). However several other studies done among university students reported females to have significantly greater academic stress than males (Adiele et al. 2018; Bamuhair et al. 2015; Reddy et al. 2018; Al-Sowygh et al. 2013).

Academic stress was found to be more among medical students in the first year (Nakalema and Ssenyonga 2014; Abdulghani 2008) or in the final year (Bamuhair et al. 2015). This was in contrast to the findings in this study were no such association was observed.

Place of residence was not associated with academic stress in this study and also in the study done among medical students in Iran by Mostafavian et al. (2018).

Academic stress in the present study was found to be least among participants who were staying with their parents, siblings or relatives. This may be because, number of students at this setting are outsiders. Studying over here, might also be their first occasion of moving out of their home environment. They therefore may be lacking their previously learnt support system such as banking on their family members and childhood friends during difficult times, as also observed by Kumar and Nancy (2011). They now have to find solutions to various problems by themselves, or by being dependent looking out for newer social contacts. If they were staying with their family members, perhaps they might have received the necessary emotional support during examinations and other stressful situations. The other benefits like getting hygienic food, good living conditions and people to take care of one’s health would have been best when family members were around. The observations in this study were however contradicting the observation of Mostafavian et al. (2018) who observed that the academic stress was significantly more among those living at their houses compared to those at dormitories.

As many as 60% participants regretted having wasted time set apart for their studies. Poor time management was found to be associated with academic stress by other researchers too (Misra and McKean 2000; Macan et al. 1990). Good time management skills involves prioritization of activities and judicious usage of time available for organization of the tasks to be completed. Time management was found to determine academic performance by Misra and McKean (2000). Moreover those with sound time management behaviour were found to have fewer psychological and physical symptoms related to stress (Misra and McKean 2000; Macan et al. 1990). Lammers et al. (2001) reported that close to half of the students had notable weaknesses in their time management skills.

Fear of failure in exams and falling short of attendance towards the end were the reasons for academic stress among more than half the participants in this study. Teachers can play an important role in alleviating examination related fears and anxieties by conducting frequent mock examinations (Sharma et al. 2011). Meeting individual students’ needs (Aherne et al. 2016), to find out the reason for missing classes, time scheduling of activities and providing constructive feedback to students (Sharma et al. 2016) are the other recommended strategies advised by previous researchers. Abouserie (1994) stated that the amount of guidance and support offered by teachers would be a key factor in determining the stress levels of students in any institution. Students themselves have opined that social support from teachers and peer groups, consulting services, and various extracurricular activities are the most useful strategies to deal with stress (Chang et al. 2012). As opined by the student community themselves, every institution need to offer them psychotherapy sessions, trainings for reducing emotional tension and opportunities to improve social intelligence (Ruzhenkov et al. 2016).

Issues like worrying about future and poor self-esteem among participants in this study were significantly associated with academic stress in the multivariable analysis model. These problems may be related to issues like concern about clearing the increasingly competitive entrance exams and also about the fear of them not being able to pursue the specialty of their choice in future. To address such sensitive problems, there is a need of the placement of a professional counsellor at various professional colleges. Pressley and McCormick (1995) also suggested that the learning environment within classrooms should be non-competitive, collaborative and task-oriented and not performance oriented, so as to create a stress free learning environment.

Having said this, the course work at medical schools should not be too light either. Kanter (2008) suggested that this approach can affect the quality of education. Rather students need to be trained in the right way to directly solve the problems related to academic stress by themselves being a part of a self-help program (Chen et al. 2013; Aherne et al. 2016).

The various sources of academic stress among medical students listed in other studies were, vastness of curriculum as reported by 61.6% (Anuradha et al. 2017), 82.2% (Bamuhair et al. 2015), and 82.3% (Oku et al. 2015), fear of failure in examination by 61.8% (Anuradha et al. 2017), frequency of examination by 52.2% (Anuradha et al. 2017), lack of recreation and inadequate holidays by 51.8% (Anuradha et al. 2017) and by 76.4% (Oku et al. 2015), sleep related problems by 64.3% (Bamuhair et al. 2015), worrying about future by 78.2% (Bamuhair et al. 2015), family problems by 54% (Bamuhair et al. 2015), interpersonal conflicts by 57.1% (Bamuhair et al. 2015), low self-esteem by 51.7% (Bamuhair et al. 2015) and transportation problems by 56.2% participants (Bamuhair et al. 2015).

Coping with stress was found to be average among 95% participants in the present study. Almost three-fourth of the participants in the present study tried to think or do something that would make them feel happier and relaxed when they were stressed. Coping methods commonly used by students in previous studies were effective time management, sharing of problems, planned problem solving, going out with friends, social support, meditation and getting adequate sleep. Even emotion-based strategies to cope stress like self-blaming and taking self-responsibility have been reported (Wolf 1994; Supe 1998; Stern et al. 1993; Redhwan et al. 2009).

Coping with stress in this study was better among participants with higher levels of academic stress which was similarly observed among Saudi Arabian medical students by Bamuhair et al. (2015). This suggests that students who perceived greater academic stress where in a position to apply coping strategies against it in a much better way. However the significant correlation between academic stress scores and passive emotional and passive problem scores indicates that the coping behaviour adopted by participants to deal with stress was not satisfactory. Therefore counselling the participants to adopt active coping behaviours is very essential at this setting. In a study done in Ghana by Atindanbila and Abasimi (2011), wrong or inadequate coping strategies were practiced by university students resulting in reduction of academic stress by mere 4%. Bamuhair et al. (2015) observed that 32.1% medical students felt too often that, they could not cope with stress. Therefore coping strategies against academic stress among university students in other parts of the world was not satisfactory either. The coping strategies adopted are generally found to vary depending on socio-cultural factors like region, social group, gender, age, and by individuals’ previous experiences as per the WHO/EHA (1998).

Passive emotional and problem coping behaviours were significantly more among males. This meant that males adopted a number of unhealthy behaviours to deal with academic stress. Unpleasant social coping behaviour was found to reduce social support and increase loneliness by Kato (2002). Felsten (1998) observed that specifically procrastination as a coping behaviour was found to result in depression in both men and women.

Female students on the other hand had significantly better active problem scores under coping behaviour. They were hence more mature and composed than the male participants in analysing the centre of the problem in a calm and optimistic manner, and in finding solutions for the same. Bamuhair et al. (2015) observed that the mean of coping strategies score was significantly higher among females. Females were also found to be better at time management compared to their male counterparts (Misra and McKean 2000; Khatib 2014). Males therefore need to be counselled about healthy coping behaviours in dealing with academic stress.

Al-Sowygh et al. (2013) observed that the denial and behaviour disengagement as stress coping strategies were reported to be significantly more among females while self-blame was reported to be more among males. Bang (2009) reported that the coping mechanism of choice is related to the differences in the roles expected from gender. Males are expected to deal stressful situations by their outward actions while females are expected to focus on emotions and seek social support. Soffer (2010) stated that women usually choose health-promoting behaviours while men prefer health-risky behaviours.

There was no association between age of participants with the perceived level of academic stress or with the level of adaptability to cope with it in this study supporting the observations of Bamuhair et al. (2015).

Limitations

This was a cross-sectional study conducted in a single medical college. Therefore the findings of this study cannot be generalized to all medical students across India.

Conclusion

The results of the study reflect important insights into the nature of stress faced by the medical students and the ways they deal with the same. Academic stress was found to be common and was of moderate level in more than three-fourth of the participants. Level of coping with stress was found to be average among 95% of them. Worrying about future and poor self-esteem were independently associated with academic stress among students. Male participants adopted more of unhealthy means of coping with academic stress. Therefore they need to be educated regarding the healthy coping methods. Counselling sessions and other students’ support systems need to be more organized to cater to the issues like career guidance, healthy coping behaviours, time management and to improve the self-esteem among the affected. Attention should also be paid to make the study environment in the classrooms more stress free without excessive academic load. Educating students about unpleasant consequences of stress is equally important. Teachers can also play a constructive role in mentoring and guiding students regarding choosing the right measures to cope with stress. Interactive academic sessions on stress control can further encourage medical students to single out each and every problematic issue. This would accomplish the aim of reducing the academic stress, adopting healthy academic stress coping behaviours, improving academic performance and minimizing anxiety among those with forethoughts about their future professional careers.

References

Abdulghani, H. M. (2008). Stress and depression among medical students: A cross sectional study at a medical College in Saudi Arabia. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, 24, 12–17.

Abouammoh, N., Irfan, F., & AlFaris, E. (2020). Stress coping strategies among medical students and trainees in Saudi Arabia: A qualitative study. BMC Medical Education, 20, 124.

Abouserie, R. (1994). Sources and levels of stress in relation to locus of control and self-esteem in university students. Educational Psychology, 14, 323–330.

Adiele, D., Judith, C. A., Morgan, G. P., Catherine, B., & Carolyne, L. M. (2018). Association of academic stress, anxiety and depression with social-demographic among medical students. International Journal of Social Science Studies, 6, 27–32.

Afolayan, J. A., Donald, B., Onasoga, O., Babafemi, A. A., & Juan, A. A. (2013). Relationship between anxiety and academic performance of nursing students, Niger Delta University, Bayelsa state, Nigeria. Advances in Applied Science Research, 4, 25–33.

Aherne, D., Farrant, K., Hickey, L., Hickey, E., McGrath, L., & McGrath, D. (2016). Mindfulness based stress reduction for medical students: Optimising student satisfaction and engagement. BMC Med Education, 16, 209.

Al-Dubai, S. A. R., Al-Naggar, R. A., Alshagga, M. A., & Rampal, K. G. (2011). Stress and coping strategies of students in a medical faculty in Malaysia. Malaysian Journal of Medical Sciences, 18, 57–64.

Al-Sowygh, Z. H., Alfadley, A. A., Al-Saif, M. I., & Al-Wadei, S. H. (2013). Perceived causes of stress among Saudi dental students. King Saud University Journal of Dental Sciences, 4, 7–15.

Anuradha, R., Dutta, R., Raja, J. D., Sivaprakasam, P., & Patil, A. B. (2017). Stress and stressors among medical undergraduate students: A cross-sectional study in a private medical college in Tamil Nadu. Indian Journal of Community Medicine, 42, 222–225.

Atindanbila, S., & Abasimi, E. (2011). Depression and coping strategies among students in the university of Ghana. Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, 2, 1257–1266.

Bamuhair, S, S., AlFarhan, A, I., Althubaiti, A., Agha, S., Rahman, S., & Ibrahim, N, O. (2015). Sources of stress and coping strategies among undergraduate medical students enrolled in a problem-based learning curriculum. Journal of Biomedical Education, 2015, Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/6a13/927839fe0df5b749c76112b70bea3f349cc1.pdf.

Bang, E. (2009). The effects of gender, academic concerns, and social support on stress for international students (Master’s thesis). Columbia: University of Missouri.

Chang, E., Eddins-Folensbee, F., & Coverdale, J. (2012). Survey of the prevalence of burnout, stress, depression, and the use of supports by medical students at one school. Academic Psychiatry, 36, 177–182.

Chawla, K., & Sachdeva, V. (2018). Domains of stress and coping strategies used by 1st year medical students. National Journal of Physiology, Pharmacy and Pharmacology, 8, 366–369.

Chen, J., Wu, Y., Yi, H., Li, Z., Eshita, Y., Qin, P., Chen, L., & Sun, J. (2013). The impact of academic stress on medical students attending college in the Inner Mongolia area of China. Open Journal of Preventive Medicine, 3, 149–154.

Deb, S., Strodl, E., & Sun, J. (2015). Academic stress, parental pressure, anxiety and mental health among Indian high school students. International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, 5, 26–34.

Drolet, B. C., & Rodgers, S. (2010). A comprehensive medical student wellness program--design and implementation at Vanderbilt School of Medicine. Academic Medicine, 85, 103–110.

Dyrbye, L. N., Thomas, M. R., Massie, F. S., Power, D. V., Eacker, A., Harper, W., & Shanafelt, T. D. (2008). Burnout and suicidal ideation among U.S. medical students. Annals of Internal Medicine., 149, 334–341.

Felsten, G. (1998). Use of distinct strategies and associations with stress and depression. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 11, 189–198.

Gade, S., Chari, S., & Gupta, M. (2014). Perceived stress among medical students: To identify its sources and coping strategies. Archives of Medicine and Health Sciences, 2, 80–86.

Kanter, S. L. (2008). Toward a sound philosophy of pre- medical education. Academic Medicine, 83, 423–424.

Kato, T. (2002). The role of the social interaction in the interpersonal stress process. Japanese Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 41, 147–154.

Khatib, A. S. A. (2014). Time management and its relation to students’ stress, gender and academic achievement among sample of students at Al Ain University of Science and Technology, UAE. International Journal of Business and Social Research, 4, 47–58.

Kumar, R., & Nancy. (2011). Stress and coping strategies among nursing students. Nursing and Midwifery Research Journal, 7, 141–151.

Kumaraswamy, N. (2013). Academic stress, anxiety and depression among college students - a brief review. International Review of Social Sciences and Humanities, 5, 135–143.

Lammers, W. J., Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Slate, J. R. (2001). Academic success as a function of the sex, class, age, study habits, and employment of college students. Research in the Schools, 8, 71–81.

Lin, Y. M., & Chen, F. S. (2009). Academic stress inventory of students at universities and colleges of technology. World Transactions on Engineering and Technology Education, 7, 157–162.

Lin, Y. M., & Chen, F. S. (2010). A stress coping style inventory of students at universities and colleges of technology. World Transactions on Engineering and Technology Education, 8, 67–72.

Lumley, M. A., & Provenzano, K. M. (2003). Stress management through emotional disclosure improves academic performance among college students with physical symptoms. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95, 641–649.

Macan, T. H., Shahani, C., Dipboye, R. L., & Phillips, A. P. (1990). College students' time management: Correlations with academic performance and stress. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82, 760–768.

Malathi, A., & Damodaran, A. (1999). Stress due to exams in medical students - a role of yoga. Indian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology, 43, 218–224.

Misra, R., & McKean, M. (2000). College students’ academic stress and its relation to their anxiety, time management, and leisure satisfaction. American Journal of Health Studies, 16, 41–51.

Mostafavian, Z., Farajpour, A., Ashkezari, S. N., & Shaye, Z. A. (2018). Academic burnout and some related factors in medical students. Journal of Ecophysiology and Occupational Health, 18, 1–5.

Nakalema, G., & Ssenyonga, J. (2014). Academic stress: Its causes and results at a Ugandan University. African journal of teacher education, 3. Retrieved from: File:///C:/users/HP/AppData/local/Microsoft/windows/INetCache/IE/H0X2S1I4/2762-article%20Text-16451-1-10-20140414.Pdf.

Oku, A. O. O., Owoaje, E. T., Oku, O. O., & Ikpeme, B. M. (2015). Prevalence of stress, stressors and coping strategies among medical students in a Nigerian medical school. African Journal of Medical and Health Sciences, 14, 29–34.

Pressley, M., & McCormick, C. (1995). Cognition, teaching, and assessment. New York: Harpercollins College Div.

Ramli, N. H. H., Alavi, M., Mehrinezhad, S. A., & Ahmadi, A. (2018). Academic stress and self-regulation among university students in Malaysia: Mediator role of mindfulness. Behavioral Sciences, 8, 12.

Reddy, J. K., Karishmarajanmenon, M. S., & Thattil, A. (2018). Academic stress and its sources among university students. Biomedical & Pharmacology Journal, 11, 531–537.

Redhwan, A. A. N., Sami, A. R., Karim, A. J., Chan, R., & Zaleha, M. I. (2009). Stress and coping strategies among management and science university students: A qualitative study. The International Medical Journal, 8, 11–15.

Royal College of Psychiatrists. (2011). Mental health of students in higher education, London. (College report CR166). Retreived from: https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/default-source/improving-care/better-mh-policy/college-reports/college-report-cr166.pdf?sfvrsn=d5fa2c24_2

Ruzhenkov, V. A., Zhernakova, N. I., Ruzhenkova, V. V., Boeva, A. V., Moskvitina, U. S., Gomelyak, Y. N., & Yurchenko, E. A. (2016) Medical and psychological effectiveness of the discipline “psychological correction of crisis conditions” first-year students of medical affairs and pediatrics faculty. Medicine series. Pharmacy, 12, 106–110.

Sharififard, F., Nourozi, K., Hosseini, M. A., Asayesh, H., & Nourozi, M. (2014). Related factors with academic burnout in nursing and paramedics students of Qom University of Medical Sciences in 2014. Journal of Nursing Education, 3, 56–68.

Sharma, B., Wavare, R., Deshpande, A., Nigam, R., & Chandorkar, R. (2011). A study of academic stress and its effect on vital parameters in final year medical students at SAIMS medical college, Indore, Madhya Pradesh. Biomedical Research, 22, 361–365.

Sharma, B., Kumar, A., & Sarin, J. (2016). Academic stress, anxiety, remedial measures adopted and its satisfaction among medical students: A systematic review. International Journal of Health Sciences and Research, 6, 368–376.

Soffer, M. (2010). The role of stress in the relationships between gender and health-promoting behaviours. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 24, 572–580.

Stern, M., Norman, S., & Komm, C. (1993). Medical students’ differential use of coping strategies as a function of stress or type, year of training, and gender. Behavioral Medicine, 18, 173–180.

Supe, A. N. (1998). A study of stress in medical students at Seth G.S. medical college. Journal of Postgraduate Medicine, 44, 1–6.

Verma, S., Sharma, D., & Larson, R. W. (2002). School stress in India: Effects on time and daily emotions. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 26, 500–508.

WHO/EHA. (1998). Emergency health training programme for Africa. Coping mechanisms. Panafrican Emergency Training Centre, Addis Ababa. Retrieved from: http://apps.who.int/disasters/repo/5517.pdf.

Wolf, T. M. (1994). Stress, coping and health: Enhancing well-being during medical school. Medical Education, 28, 8–17.

Wu, L., Farquhar, J., Ma, J., & Vidyarthi, A. R. (2018). Understanding Singaporean medical students’ stress and coping. Singapore Medical Journal, 59, 172–176.

Zamroni, H. N., Ramli, M., & Hambali, I. M. (2018). Prevalence of academic stress among medical and pharmaceutical students. European Journal of Education Studies, 4, 256–267.

Acknowledgements

We authors thank all the medical students of who took part in this study.

Contribution by Authors

This manuscript has been read and approved by all the authors, the requirements for authorship as stated earlier in this document have been met, and each author believes that the manuscript represents honest work.

Nitin Joseph: guarantor of this research work, design, literature search, tool preparation, manuscript preparation, revising the work critically for important intellectual content.

Aneesha Nallapati: data collection, data analysis, statistical analysis, interpretation of data, revising the work critically for important intellectual content.

Mitchelle Xavier Machado: data collection, data entry, literature search, manuscript preparation, manuscript editing, revising the work critically for important intellectual content.

Varsha Nair: concept of this study, data collection, data entry, manuscript editing, revising the work critically for important intellectual content.

Shreya Matele: data collection, literature search, manuscript editing, revising the work critically for important intellectual content.

Navya Muthusamy: data collection, literature search, manuscript editing, revising the work critically for important intellectual content.

Aditi Sinha: data collection, literature search, manuscript editing, revising the work critically for important intellectual content.

All authors approved the final manuscript before submission.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Source of support: Nil.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Joseph, N., Nallapati, A., Machado, M.X. et al. Assessment of academic stress and its coping mechanisms among medical undergraduate students in a large Midwestern university. Curr Psychol 40, 2599–2609 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00963-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00963-2