Abstract

Scleroglucan is a β-glucan exopolysaccharide (EPS) efficiently produced by Sclerotium rolfsii ATCC 201126, with attractive properties for a wide range of industries. Its production was herein comparatively assessed with nine alternative C- and twelve N-sources. When comparing conventional sucrose-based Production Medium PM20 (8.41 g C/L + NaNO3 as N-source) at shake-flask-scale vs. alternative C-source versions, soluble starch and sugarcane molasses led to efficient EPS production. At bioreactor scale, starch-based medium led to highest EPS production (7.95 g/L), recovery (~ 52%) and productivities (0.11 g EPS/L h; 0.018 g EPS/gbiomass h). Molasses, though leading to lower EPS production (5.11 g/L), could be envisaged as a promising agroindustrial sub-product for adding value and innovation. Oxalate side-product varied with C- and N-sources, with no clear detrimental relationship with EPS production. Agroindustrial sub-products showed then to be suitable as alternative substrates for efficient, low-cost, and scalable EPS production, thus opening new perspectives for medium reformulation and sustainable EPS production.

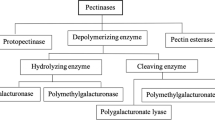

source: 1 corn starch, 2 soluble starch, 3 cassava starch. Activities were confronted against different substrates (soluble, corn and cassava starch at 40 g/L, starch-Azure at 0.5 g/L) and with different detection methods (direct or developed with I2). Results correspond to 24 h of incubation at 37 °C. Positive controls include: α-amylase from A. oryzae Type X-A (crude) (α-A), β-amylase from sweet potato Type I-B (β-A), and amyloglucosidase from A. niger (AG). For further details, see “Material and Methods” section

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Castillo NA, Valdez AL, Fariña JI (2015) Microbial production of scleroglucan and downstream processing. Front Microbiol 6:1106

Donot F, Fontana A, Baccou JC, Schorr-Galindo S (2012) Microbial exopolysaccharides: main examples of synthesis, excretion, genetics and extraction. Carbohydr Polym 87:951–962

Fariña JI, Siñeriz F, Molina OE, Perotti NI (1998) High scleroglucan production by Sclerotium rolfsii: influence of medium composition. Biotechnol Lett 20:825–831

Fariña JI, Siñeriz F, Molina OE, Perotti NI (2001) Isolation and physicochemical characterization of soluble scleroglucan from Sclerotium rolfsii rheological properties, molecular weight and conformational characteristics. Carbohydr Polym 44:41–50

Giavasis I, Harvey LM, McNeil B (2005) Scleroglucan. Biopolym Online. https://doi.org/10.1002/3527600035.bpol6002

Halleck FE (1967) Polysaccharides and methods for production thereof. Patent No 3,301,848

Schmid J, Meyer V, Sieber V (2011) Scleroglucan: biosynthesis, production and application of a versatile hydrocolloid. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 91:937–947

Survase SA, Saudagar PS, Bajaj IB, Singhal RS (2007) Scleroglucan: fermentative production, downstream processing and applications. Food Technol Biotechnol 45:107–118

Wang Y, McNeil B (1996) Scleroglucan. Crit Rev Biotechnol 16:185–215

Brigand G (1993) Scleroglucan. In: Industrial gums, 3rd edn. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 461–474

Falch BH, Espevik T, Ryan L, Stokke BT (2000) The cytokine stimulating activity of (1 → 3)-β-d-glucans is dependent on the triple helix conformation. Carbohydr Res 329:587–596

Giavasis I (2014) Bioactive fungal polysaccharides as potential functional ingredients in food and nutraceuticals. Curr Opin Biotechnol 26:162–173

Laroche C, Michaud P (2007) New developments and prospective applications for β (1,3) glucans. Recent Pat Biotechnol 1:59–73

Pretus HA, Ensley HE, McNamee RB et al (1991) Isolation, physicochemical characterization and preclinical efficacy evaluation of soluble scleroglucan. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 257:500–510

Viñarta SC (2009) Biopolímero escleroglucano: preparación, caracterización fisico-química y molecular, actividad biológica. Relación estructura-función y potencial aplicación fármaco-industrial. PhD Thesis, Universidad Nacional de Tucumán

Viñarta SC, François NJ, Daraio ME et al (2007) Sclerotium rolfsii scleroglucan: the promising behavior of a natural polysaccharide as a drug delivery vehicle, suspension stabilizer and emulsifier. Int J Biol Macromol 41:314–323

Vos AP, M’Rabet L, Stahl B et al (2007) Immune-modulatory effects and potential working mechanisms of orally applied nondigestible carbohydrates. Crit Rev Immunol 27(2):97–104

Wang Y, McNeil B (1995) Production of the fungal exopolysaccharide scleroglucan by cultivation of Sclerotium glucanicum in an airlift reactor with an external loop. J Chem Technol Biotechnol Int Res Process Environ Clean Technol 63:215–222

Schilling BM (2000) Sclerotium rolfsii ATCC 15205 in continuous culture: economical aspects of scleroglucan production. Bioprocess Eng 22:57–61

Fariña JI, Siñeriz F, Molina OE, Perotti NI (1996) Low-cost method for the preservation of Sclerotium rolfsii Proimi F-6656: inoculum standardization and its use in scleroglucan production. Biotechnol Technol 10:705–708

Survase SA, Saudagar PS, Singhal RS (2006) Production of scleroglucan from Sclerotium rolfsii MTCC 2156. Bioresour Technol 97:989–993

Abidin AZ, Puspasari T, Nugroho WA (2012) Polymers for enhanced oil recovery technology. Procedia Chem 4:11–16

Palaniraj A, Jayaraman V (2011) Production, recovery and applications of xanthan gum by Xanthomonas campestris. J Food Eng 106:1–12

Castillo NA, Valdez AL, Fariña JI (2017) Biopolymers of microbial origin. In: Advances in physicochemical properties of biopolymers (Part 2). Bentham Science Publishers, Sharjah, pp 109–193

Fosmer A, Gibbons WR, Heisel NJ (2010) Reducing the cost of scleroglucan production by use of a condensed corn solubles medium. J Biotechnol Res 2:131–143

Wang Y, McNeil B (1994) Scleroglucan and oxalic acid formation by Sclerotium glucanicum in sucrose supplemented fermentations. Biotechnol Lett 16:605–610

Fosmer A, Gibbons W (2011) Separation of scleroglucan and cell biomass from Sclerotium glucanicum grown in an inexpensive, by-product based medium. Int J Agric Biol Eng 4:52–60

Virtanen S, Chowreddy RR, Irmak S et al (2017) Food industry co-streams: potential raw materials for biodegradable mulch film applications. J Polym Environ 25:1110–1130

Survase SA, Saudagar PS, Singhal RS (2007) Use of complex media for the production of scleroglucan by Sclerotium rolfsii MTCC 2156. Bioresour Technol 98:1509–1512

Abeygunawardena DVW, Wood RKS (1957) Factors affecting the germination of sclerotia and mycelial growth of Sclerotium rolfsii Sacc. Trans Br Mycol Soc 40:221–231

Bateman D, Beer S (1965) Simultaneous production and synergistic action of oxalic acid and polygalacturonase during pathogenesis by Sclerotium rolfsii. Phytopathology 55:204–211

Maxwell PD, Bateman FD (1968) Influence of carbon source and pH on oxalate accumulation in culture filtrates of Sclerotium rolfsii. Phytopathology 58:1351–1355

Miller GL (1959) Use of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugar. Anal Chem 31:426–428

Dubois M, Gilles KA, Hamilton JK et al (1956) Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal Chem 28:350–356

Koroleff F, Grasshoff K (1976) Determination of ammonia, phosphorus and silicon. In: Grasshoff K (ed) Methods of seawater analysis. Verlag Chemie, Weinheim, pp 127–133

Dutton MV, Rastall RA, Evans CS (1991) Improved high-performance liquid chromatographic separation for the analysis of oxalate in fungal culture media. J Chromatogr A 587:297–299

González CF, Fariña JI, Figueroa LIC (2002) A critical assessment of a viscometric assay for measuring Saccharomycopsis fibuligera α-amylase activity on gelatinised cassava starch. Enzyme Microb Technol 30:169–175

Fariña JI (2005) Biotecnología de polisacáridos microbianos. In: Navarro AR, Maldonado MC, Rubio MC (eds) Biotecnología microbiana 1, 1st edn. Imprenta Central de la Universidad Nacional de Tucumán, SM Tucumán, pp 181–206

Sutherland IW (1982) Biosynthesis of microbial exopolysaccharides. Adv Microb Physiol 23:79–150

Okon Y, Chet I, Kislev N, Henis Y (1974) Effect of lactose on soluble-glucan production and on the ultrastructure of Sclerotium rolfsii Sacc. grown in submerged culture. Microbiology 81:145–149

Okon Y, Chet I, Henis Y (1975) The effect of glucose and lactose on β-d-galactosidase activity and formation of sclerotia in Sclerotium rolfsii. Can J Microbiol 21:1123–1126

Bolla K, Gopinath BV, Shaheen SZ, Charya MAS (2010) Optimization of carbon and nitrogen sources of submerged culture process for the production of mycelial biomass and exopolysaccharides by Trametes versicolor. Mol Biol 1:15–21

Souw P, Demain AL (1979) Nutritional studies on xanthan production by Xanthomonas campestris NRRL B1459. Appl Environ Microbiol 37:1186–1192

Pany VK, Apparao A (1963) Studies on the nutritional physiology of Sclerotium rolfsii Sacc. Proc Indian Acad Sci 57:326

Selbmann L, Crognale S, Petruccioli M (2002) Exopolysaccharide production from Sclerotium glucanicum NRRL 3006 and Botryosphaeria rhodina DABAC-P82 on raw and hydrolysed starchy materials. Lett Appl Microbiol 34:51–55

Schmid J (2011) Genetics of scleroglucan production by Sclerotium rolfsii. PhD Thesis, Technische Universität Berlin

Chandra R, Bharagava RN, Rai V (2008) Melanoidins as major colourant in sugarcane molasses based distillery effluent and its degradation. Bioresour Technol 99:4648–4660

Prabakar D, Suvetha KS, Manimudi VT et al (2018) Pretreatment technologies for industrial effluents: critical review on bioenergy production and environmental concerns. J Environ Manage 218:165–180

Tsioptsias C, Lionta G, Deligiannis A, Samaras P (2016) Enhancement of the performance of a combined microalgae-activated sludge system for the treatment of high strength molasses wastewater. J Environ Manage 183:126–132

Chingono KE, Sanganyado E, Bere E, Yalala B (2018) Adsorption of sugarcane vinasse effluent on bagasse fly ash: a parametric and kinetic study. J Environ Manage 224:182–190

Lazaridou A, Roukas T, Biliaderis CG, Vaikousi H (2002) Characterization of pullulan produced from beet molasses by Aureobasidium pullulans in a stirred tank reactor under varying agitation. Enzyme Microb Technol 31:122–132

Lee IY, Seo WT, Kim GJ et al (1997) Production of curdlan using sucrose or sugar cane molasses by two-step fed-batch cultivation of Agrobacterium species. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 18:255–259

Kalogiannis S, Iakovidou G, Liakopoulou-Kyriakides M et al (2003) Optimization of xanthan gum production by Xanthomonas campestris grown in molasses. Process Biochem 39:249–256

Vedyashkina TA, Revin VV, Gogotov IN (2005) Optimizing the conditions of dextran synthesis by the bacterium Leuconostoc mesenteroides grown in a molasses-containing medium. Appl Biochem Microbiol 41:361–364

Küçükaşik F, Kazak H, Güney D et al (2011) Molasses as fermentation substrate for levan production by Halomonas sp. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 89:1729–1740

Yilmaz M, Celik GY, Aslim B, Onbasili D (2012) Influence of carbon sources on the production and characterization of the exopolysaccharide (EPS) by Bacillus sphaericus 7055 strain. J Polym Environ 20:152–156

Özcan E, Öner ET (2015) Microbial production of extracellular polysaccharides from biomass sources. In: Ramawat K, Mérillon JM (eds) Polysaccharides. Springer, Cham, pp 161–184

Cui YW, Zhang HY, Ji SY, Wang ZW (2017) Kinetic analysis of the temperature effect on polyhydroxyalkanoate production by Haloferax mediterranei in synthetic molasses wastewater. J Polym Environ 25:277–285

Viñarta SC, Yossen MM, Vega JR et al (2013) Scleroglucan compatibility with thickeners, alcohols and polyalcohols and downstream processing implications. Carbohydr Polym 92:1107–1115

Pajot HF, de Figueroa LIC, Fariña JI (2007) Dye-decolorizing activity in isolated yeasts from the ecoregion of Las Yungas (Tucumán, Argentina). Enzyme Microb Technol 40:1503–1511

Fariña JI, Santos VE, Perotti NI et al (1999) Influence of the nitrogen source on the production and rheological properties of scleroglucan produced by Sclerotium rolfsii ATCC 201126. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 15:309–316

Selbmann L, Onofri S, Fenice M et al (2002) Production and structural characterization of the exopolysaccharide of the Antarctic fungus Phoma herbarum CCFEE 5080. Res Microbiol 153:585–592

Badr-Eldin SM, El-Tayeb OM, El-Masry HG et al (1994) Polysaccharide production by Aureobasidium pullulans: factors affecting polysaccharide formation. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 10:423–426

Kudryashova OA, Yurlova NA (2000) Effect of the nitrogen source on the biosynthesis, composition, and structure of the exopolysaccharides of Aureobasidium pullulans (de Bary) arnaud. Microbiology 69:428–435

Seviour RJ, Kristiansen B (1983) Effect of ammonium ion concentration on polysaccharide production by Aureobasidium pullulans in batch culture. Eur J Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 17:178–181

Stasinopoulos SJ, Seviour RJ (1989) Exopolysaccharide formation by isolates of Cephalosporium and Acremonium. Mycol Res 92:55–60

Gibbs PA, Seviour RJ (1998) The production of exopolysaccharides by Aureobasidium pullulans in fermenters with low-shear configurations. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 49:168–174

Reeslev M, Jørgensen BB, Jørgensen OB (1996) Exopolysaccharide production and morphology of Aureobasidium pullulans grown in continuous cultivation with varying ammonium-glucose ratio in the growth medium. J Biotechnol 51:131–135

Chakrabarti K, Samajpati N (1980) Effect of different nitrogen sources on the yield of oxalic acid by Sclerotium rolfsii. Folia Microbiol 25:498–500

Liu TME, Wu LC (1971) Effect of amino acids on the growth and morphogenesis of Sclerotium rolfsii Sacc. Plant Prot Bull 13:87–96

Narasimhan R (1970) Physiological studies on the genus Sclerotium. Proc Indian Acad Sci 71:50–55

Punja ZK, Jenkins SF (1984) Influence of medium composition on mycelial growth and oxalic acid production in Sclerotium rolfsii. Mycologia 76:947–950

Marzluf GA (1997) Genetic regulation of nitrogen metabolism in the fungi. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 61:17–32

Weiss RL (1976) Compartmentation and control of arginine metabolism in Neurospora. J Bacteriol 126:1173–1179

Willetts AJ (1972) Metabolism of threonine by Fusaria growth on threonine as the sole carbon and nitrogen source. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 38:591–603

Kritzman G, Okon Y, Chet I, Henis Y (1976) Metabolism of l-threonine and its relationship to sclerotium formation in Sclerotium rolfsii. J Gen Microbiol 95:78–86

Vyas KM, Saksena SB (1973) Studies on mycelial respiration of Sclerotium rolfsii. Proc Indian Natl Sci Acad B 39:569–575

Sarma BK, Singh UP, Singh KP (2002) Variability in Indian isolates of Sclerotium rolfsii. Mycologia 94:1051–1058

Chet I, Henis Y (1972) The response of two types of Sclerotium rolfsii to factors affecting sclerotium formation. Microbiology 73:483–486

Kritzman G, Chet I, Henis Y (1977) The role of oxalic acid in the pathogenic behavior of Sclerotium rolfsii Sacc. Exp Mycol 1:280–285

Kinghorn JR, Pateman J (1977) Nitrogen metabolism. In: Smith JE, Pateman JA (eds) Genetics and physiology of Aspergillus. Academic Press Inc., London, pp 147–202

Roukas T, Liakopoulou-Kyriakides M (1999) Production of pullulan from beet molasses by Aureobasidium pullulans in a stirred tank fermentor. J Food Eng 40:89–94

Holzwarth G (1984) Xanthan and scleroglucan: structure and use in enhanced oil recovery. Dev Ind Microbiol 26:271–280

Sandford PA (1979) Exocellular, microbial polysaccharides. Adv Carbohydr Chem Biochem 36:265–313

Coviello T, Palleschi A, Grassi M et al (2005) Scleroglucan: A versatile polysaccharide for modified drug delivery. Molecules 10:6–33

Chavan MN, Dandi ND, Kulkarni MV, Chaudhari AB (2013) Biotreatment of melanoidin-containing distillery spent wash effluent by free and immobilized Aspergillus oryzae MTCC 7691. Water Air Soil Pollut 224:1755–1764

Campos R, Kandelbauer A, Robra KH et al (2001) Indigo degradation with purified laccases from Trametes hirsuta and Sclerotium rolfsii. J Biotechnol 89:131–139

Ryan S, Schnitzhofer W, Tzanov T et al (2003) An acid-stable laccase from Sclerotium rolfsii with potential for wool dye decolourization. Enzyme Microb Technol 33:766–774

Kelkar HS, Deshpande MV (1993) Purification and characterization of a pullulan-hydrolyzing glucoamylase from Sclerotium rolfsii. Starch-Stärke 45:361–368

Acknowledgements

The study was financially supported by the National Council for Scientific and Technical Research (CONICET) (Grant PIP0976), the National University of Catamarca (UNCa) (Grant PIO-UNCa 0100054), and the National Agency for the Promotion of Science and Technology (ANPCyT) along with the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (Bilateral Cooperation project CONICET-MINCyT-DFG level II). Authors gratefully acknowledge Lic. María Florencia Ladetto for critical analyses of FT-IR spectra.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Valdez, A.L., Babot, J.D., Schmid, J. et al. Scleroglucan Production by Sclerotium rolfsii ATCC 201126 from Amylaceous and Sugarcane Molasses-Based Media: Promising Insights for Sustainable and Ecofriendly Scaling-Up. J Polym Environ 27, 2804–2818 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10924-019-01546-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10924-019-01546-4