Abstract

Multi-sensory rooms were originally intended as a leisure option for people with severe disabilities living in institutions. Their use has extended far beyond this and proponents, particularly equipment suppliers, continue to claim a range of benefits beyond provision of a leisure experience. We review the literature on the effects of MSEs on people with developmental disabilities other than autism spectrum disorders. The research examined was predominately of very poor quality, limiting conclusions that can be drawn. MSEs were used in a variety of ways with the wide range of outcomes measured addressing reduction of challenging behaviours and promoting more desirable behaviours. The majority of reported results were mixed or negative, with better quality studies more likely to report no effects. Overall, based on the available evidence, the use of MSEs cannot be recommended as an intervention option for individuals with developmental disabilities, but they may have a limited role as a leisure option.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Since their introduction as a leisure option for people with severe disabilities living in institutions in the 1970s and 1980s (Hulsegge & Verheul, 1987), multisensory environments (MSEs) or Snoezelen rooms have become widely used in schools and the community (Botts et al., 2008), and continue to be installed in schools and elsewhere (e.g., TFH, 2023). A typical MSE is likely to be windowless and to have padding for safety on the walls and floor. It contains electrical equipment deigned to provide sensory stimulation using light and sound effects, aromas, and tactile experiences. Equipment and stimuli can include bubble tubes, fibre optics, projectors, mirror balls, music, and other sound effects, vibrating chairs or other tactile equipment and aroma diffusers (Cameron et al., 2020; Haegele & Porretta, 2014). Switches or other devices may allow users to control the equipment for stimulation or calming, or users may be passive recipients of stimulation (Cameron et al., 2020). The original concept for use did not include any intended beneficial effects outside of a relaxing leisure experience where users were supported in their preferred use of the equipment and could build a relationship with care staff (Haggar & Hutchinson, 1991).

Today MSEs are used for people with and without disabilities in schools, residential institutions, hospitals, mental-health facilities, disability services and aged care (Cameron et al., 2020). The term Snoezelen has been trademarked by the Rompa company, a major distributer of MSE equipment. Commercial firms continue to make claims for positive outcomes from the use of an MSE including reduced agitation, improved concentration and alertness, improved social and motor development, reduced aggression and improved self-esteem (Performance Health, 2023; Rhino Sensory, 2023; Rompa, 2023), which are similar to claims documented by Botts et al. (2008). Consumers may rely on information from suppliers when choosing to invest in an MSE (Carter & Stephenson, 2012).

MSEs have also moved from being a leisure option to being used as an environment for teaching specific skills such as self-regulation (Bergstrom et al., 2019; Pagliano, 1998). The lack of clear guidelines for MSE use likely reflects the lack of a coherent theoretical base, although some have used sensory processing theories from occupational therapy (Bergstrom et al., 2019) and, specifically, sensory integration theory has been applied to the use of MSEs, particularly with people with autism spectrum disorder (ASD; Botts et al., 2008; Carter & Stephenson, 2012). Theories of sensory integration and sensory processing posit that maladaptive behaviour may occur because individuals process sensory information from the environment abnormally (e.g., under- or over-sensitivivity) and this interferes with their ability to plan appropriate behavior. It is suggested that exposure to controlled sensations, such as provided by an MSE, that require the nervous system to process and integrate incoming sensory stimuli, may modify the brain (Bergstom et al., 2019; Botts et al., 2008). Pagliano (2006) makes a case for a more traditional client-led approach to use of the room for people with severe and profound disabilities, with the facilitator supporting and enabling choice. He extends this to the user acquiring skills, using the MSE until the participant can engage in the MSE, with the best result being the ability to engage and persevere with engagement in activities outside the MSE.

Prior reviews of MSEs were not totally positive noting limited studies, poor research quality, the limited evidence for generalization of effects and the diversity of approaches and outcomes measured (Hogg et al., 2001; Lancioni et al., 2002; Lotan & Gold, 2009). Chan et al. (2010) reviewed use with adults with developmental disability and found that although participants may enjoy use, there was little evidence to support use for reducing challenging behaviour or stereotypy. Unlike the earlier reviews, Chan et al. evaluated methodological quality and overall quality was rated as fair.

Cameron et al. (2020) completed a scoping review of studies of MSEs conducted between 2006 and 2016 and concluded there was the possibility of positive outcomes from MSE use, but that the evidence base was not strong and benefits for people with developmental disability were not clear. They also noted lack of clarity regarding equipment used, optimum frequency and duration of sessions, and appropriate training for practitioners. They reported that only four of the intervention studies with participants with developmental disability reviewed measured generalization, but provided no detail regarding these outcomes. In a scoping review limited to use with people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, Breslin et al. (2020) concluded there was some support for use to reduce challenging behaviour within sessions with mixed results regarding generalization. They concluded that widespread use could not be recommended. Neither of these scoping reviews provided an in-depth analysis of research designs or quality.

Individuals with ASD have been reported to have distinctive sensory issues (Proff et al., 2022; Robertson & Baron-Cohen, 2017) and hyporeactivity or hyperreactivity to sensory input is now recognised in diagnostic criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Thus, it is possible that individuals with ASD may have different reactions to the stimulation provided in MSEs to others with developmental disabilities. Authors (in press) provided a recent review of use of MSEs for individuals with ASD, which included analysis of study quality. They reported that study quality was very poor for the most part and results were inconsistent. The use of MSEs was not recommended, other than as a leisure activity and, even for this purpose, evidence is required that MSEs represent a better option than more normalised activities.

The aim of the review reported here was to analyse all studies addressing the use of MSEs for people with developmental disabilities excluding those with ASD. Unlike other reviews we analyse the research designs used and research quality. The questions guiding the review, specifically focussing on people with developmental disabilities excluding those with ASD, were:

-

1.

What is the methodological quality of studies used to examine the effectiveness of MSEs?

-

2.

How are MSEs used?

-

3.

What outcomes are examined in research on MSEs and how are they measured?

-

4.

Are MSEs an effective intervention?

Method

Search Strategy

We carried out searches in 2021 and 2023 to locate refereed journal articles describing interventions incorporating use of MSEs that included participants with developmental disability. The databases ERIC, Cinahl, PubMed and Psychinfo were searched using the terms (disbilit* OR handicap) AND (Snoezelen OR multisensory environment OR multisensory room OR multisensory therapy). Overall, there were 180 hits with 78 remaining when duplicates were removed. Both authors independently screened the abstracts and titles. Studies needed to meet the criteria of being written in English in a refereed journal, reporting an intervention that used an MSE and included participants with a developmental disability other than an ASD. Articles where it was unclear from the title and abstract if the criteria were met were retained. Eighteen articles were retained. Reliability for article inclusion was 96% (calculated using the formula agreements divided by agreements plus disagreements). Disagreements were resolved by discussion.

An ancestral search located nine additional articles. A search of the reference lists of previous reviews related to MSEs (Breslin et al., 2020; Chan et al., 2010; Haegele & Porretta, 2014; Hogg et al., 2001; Lai, 2003; Lancioni et al., 2002, 2005; Lotan & Gold, 2009) was carried out and one additional article was located. Another article (Thompson, 2011) was located incidentally that did not appear as part of our formal search. Thus, 29 articles went forward for detailed coding that was completed independently by both authors.

Data Extraction

The data extracted, as described in Authors (in press) covered (a) the research design (randomized control trial; pre-post single group; pre-post comparison group; post only single group; AB design; multiple baseline design; case study or other), (b) participant characteristics (number, gender, age, diagnosis), (c) intervention information (individual; group; number of sessions; frequency of sessions; length of sessions), (d) equipment used, (e) procedural reliability (presence and result if relevant), (f) interventionist (therapist; teacher; other), (g) location (school; residential, hospital; other), (h) comparison conditions, (i) other interventions, and (j) maintenance and (k) Measurements outside MSE (generalisation; comparison condition; other).

Where studies included participants with disabilities other than developmental disabilities or participants with ASD, the data relevant to these participants were excluded from coding. For example, in Kwok et al. (2003), the results of the group study, could not be disaggregated by disability but three relevant case studies were provided. In Thompson (2011) only the results regarding sustained focus were provided for different disability groups, and in Houghton et al. (1998) although statistical analysis for whole group results was provided, only limited descriptive statistics were available for students with developmental disability other than ASD and the results for generalisation were not disaggregated.

Some consensus coding proved necessary to identify some unclear dependent variables (e.g., conflicting information provided in the description or definition compared to what was measured and reported). In articles for which this occurred, we identified the dependent variables by consensus and subsequently coded each dependent variable independently. Further details about dependent variables and results were coded where a study provided a description of a dependent variable and either inferential or descriptive numerical data related to that variable. The details coded included the nature of the target behaviour. We originally coded behaviours under general challenging behaviour, aggression, self-injurious behaviour (SIB), stereotypy, physiological, communication, concentration, relaxation, alertness, responsiveness, adaptive behaviour and other. Behaviours were only included under these classifications if it was the actual terminology used by the authors, otherwise we included it as “other”. For example, if a specific named stereotypy was the terminology used by the authors, this was coded as other. After all the dependent variables had been coded, we reclassified behaviours coded as “other” to the categories already listed (for example, a specific named challenging behaviour such as yelling was recoded as challenging behaviour). We added two additional categories, emotional state, which covered variables such as enjoyment and agitation, and social interaction which included variables such as staff interaction and social behaviour.

Measurement systems were coded when relevant (a) the type of measurement (direct observation; third party report not based on direct observation; formal assessment task; details of the assessment task where relevant), (b) when the assessment took place (during MSE session; immediately after MSE session; later) and (c) where the assessment occurred (in the MSE: outside the MSE; not stated). We recorded whether observers were blinded, whether interrater reliability was recorded, and the results of interrater reliability where relevant. The results reported for each dependent variable were recorded as positive (favoured MSE) or negative. Given that interpretation of graphed results in single case experimental design studies is usually based on researcher judgement, both authors examined graphic data using conventional criteria (Maggin et al., 2018) and summarized overall findings, with any differences resolved by discussion.

Study Quality

In addition to extracting data from each study, each author independently assessed study quality as in Authors (in press). Case-studies and single group designs were not assessed for quality as they cannot provide evidence of causality (Campbell & Stanley, 1963). Similarly, within-subject comparisons of participations in conditions that did not involve cross-over were considered inadequate to allow for demonstration of experimental control and were not assessed further for quality. Thus, for group designs quality assessment was reserved for between subject comparisons studies and within-subject studies comparing conditions that involved crossover.

For qualifying group designs, we used the scheme described by Leong et al. (2015) for assessment of quality. The quality criteria assessed in this scheme include randomization, blinding, attrition and establishing pretest equivalence. For group designs, given the unclear descriptions of some study methodologies, the authors considered whether each study could be treated as a randomized design or not. Acceptable group designs included random assignment of participants to groups in between-subject comparisons or random assignment of participants to treatment order in within-subject crossover comparisons (i.e., when participants were exposed to multiple conditions). In assessing quality, the requirement for pre-intervention group equivalence was not applicable for within-subject crossover comparisons as contrasts were within-subject. Each study received a score out of six or eight (depending on applicability of pre-intervention group equivalence) with a maximum of two points for each criterion. For randomization, two points were awarded for use of an acceptable randomization method (e.g., coin toss, random number table), one point for a claim of randomization with no description of the process and zero points if randomization did not occur. For blinding, two points were awarded if assessors were blinded on all measures, one if they were blinded on some measures and zero if blinding did not occur. Where blinding was claimed but was not physically possible from the description provided (e.g., observations were made inside the MSE so observers could not be blind to the condition), blinding was rated as absent. For attrition, two points were awarded if differential attrition was within 10% for all groups and zero points if differential attrition was not within 10%. For studies where pretest equivalence on outcomes measures was applicable, two points were awarded if groups were shown to be statistically equivalent at pretest on all measures (or if statistical adjustments were made for differences) and zero points if pretest equivalence was not examined or if differences were not adjusted for.

For single case experimental designs that included participants with ASD as well as developmental disability, we assessed quality on the basis of all participants. For these studies we used the What Works Clearinghouse (WWC) standards (2022). The criterion for inter-observer reliability was acceptable reliability for 20% or more of data points in each condition and if this standard was not met, further quality appraisal was not completed. Designs had to provide the possibility of three demonstrations of control and if this criterion, was not met, further quality appraisal for specific designs was not completed. One multiple base-line design (Moir, 2010) and one ABAB design (Tunson & Candler, 2010) did not meet these initial criteria, so more detailed quality appraisal was not required. Two studies used alternating treatment designs and more detailed criteria were applied. There needed to be at least five data points in each condition, with a maximum of two sequential data points in the same condition, to meet the standard, or four data points to meet the standard with reservation.

Reliability for Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Reliability for data extraction and quality assessment was calculated using the formula agreements divided by agreements plus disagreements multiplied by 100. Reliability for data extraction was 94.5%. There were no disagreements regarding small-n quality. Agreement for group design quality was 87.2%. All disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Results

Research Designs

We located 29 articles reporting 29 studies, with one article (Cuvo et al., 2001) reporting two studies and one study reported in two articles (Chan et al., 2005, 2007). There were eight case studies (see Table 1). Case studies in Kwok et al., 2003 and Hong, 2004 are not included in Table 1 as no numerical data were presented.. Five articles reported six single case experimental studies with Cuvo et al. (2001) reporting two studies. The remainder of the studies were group designs, with one study reported in two articles (Chan et al., 2005, 2007) and two articles (Lindsay et al., 1997, 2001) reporting two studies with the same participants.

Participants

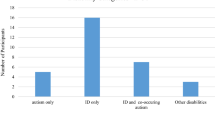

There were 496 participants that received intervention in an MSE (range 1 to 109) and 45 who were involved in studies as controls or did not receive MSE treatment. All except four studies (Chan & Chien, 2017; Fava & Strauss, 2010; Sigal & Sigal, 2022; Thompson, 2011) provided the number of males and females with developmental disabilities who completed MSE treatment and for studies that provided these data there were 190 males and 143 females. Participants were aged between 1 year 10 months and 74, with most studies reporting on adults. Only eight studies included participants under 12 years. Two studies did not report any specific diagnoses that could be coded (Sigel & Sigel, 2022; Toro, 2019) but for the remainder where a diagnosis could be coded (and noting that one participant could have more than one diagnosis) the most frequent diagnosis was severe or profound intellectual disability (n = 216), followed by mild/moderate intellectual disability (n = 71); physical disability (n = 23), vision impairment (n = 6) and hearing impairment (n = 8). Many other disabilities such as epilepsy, various syndromes and mental health disorders concurrent with developmental disability were also reported in 15 studies.

Research Design and Quality

There were eight case studies The results from case studies were not evaluated for quality as they cannot be used to impute causation. There were six single case experimental design studies, and only two of these, studies one and two in Cuvo et al., (2001) met WWC standards (see Table 1). Only one other single case experimental design study, Ashby et al., (1995), reported procedural reliability data. Koller et al. (2018) described their design as a single subject design. They compared observations taken in baseline compared to intervention (AB) and in intervention compared to baseline (BA). As only one set of data was was recorded in each condition, its quality was assessed as a group design and determined to be poor (score of 2/7).

There were a range of group designs, four of which were single group designs that did not allow for conclusive cause/effect relationships to be demonstrated (Campbell & Stanley, 1963). There was one pre/post comparison group design (score 3/8). There were two between-subject crossover designs (scores 2/8 and 3/8) and four within-subject cross-over designs (all scored 2/6) and none was of high quality There were two randomised control trials and both scored 4/8, which also indicates poor quality. In addition, procedural reliability data were only reported in two group studies (Lindsay et al., 1997, 2001).

Reliability of observation was reported in 14 studies. In two studies, observers were blind to whether or not participants had used the MSE before the observation. In two studies, authors noted that observers were blind to the purpose of the study but could not have been blind to the different conditions as some observations were conducted in the MSE (Fava & Strauss, 2010; Tunson & Candler, 2010). Lindsay et al. (2001) stated observers were blinded to the conditions, but as observations were carried out during the various treatment conditions, including the MSE, observers could not be blind to conditions. In cases where observers were blind to the purpose of the study but aware of the condition (i.e., some observations were conducted in the MSE), we did not classify this as acceptable blinding.

A number of specific weaknesses were common to many of the studies reviewed. These included missing or limited operational definitions of dependent variables (e.g., Hong, 2004; Kenyon & Hong, 1998; Lotan et al., 2009; Withers & Ensum, 1995) and instances where the clinical significance of differences for at least some outcomes were unclear (e.g., Buono et al., 2022; Fava & Strauss, 2010; Lindsay et al., 1997; Singh et al., 2004; Thompson, 2011). From statistical point of view, many authors did not make appropriate corrections for familywise error (e.g., Chan & Chien, 2017; Koller et al., 2018; Toro, 2019; Vlaskamp et al., 2003) and in some cases correlated data appear to have been treated as independent (e.g., Koller et al., 2018; Toro, 2019).

Intervention Characteristics

Eighteen studies reported that participants used the MSE in an individual session while six reported group use, one study reported both group and individual use and for four the nature of the use could not be ascertained (See Table 2). The number of sessions provided could not be ascertained for five studies and the remainder ranged between one and 208. Twelve studies reported between 10 and 20 sessions, with seven reporting fewer than 10 sessions. In Koller et al. (2018), Long and Haig (1992) and Vlaskamp et al. (2003), participants had been using the MSE for an unstated number of sessions prior to commencement of data collection. There were three studies where at least one participant received over 100 sessions. The length of sessions in the MSE varied between 10 min to one hour and was most commonly (14 studies) between 20 to 30 min.

The implementer was described as a therapist in nine studies (Ashby et al., 1995; Buono et al., 2022; Hong et al., 2004; Kenyon & Hong, 1998; Kwok et al., 2003; Lindsay et al., 1997; Lindsay et al., 2001; Lotan, 2006b; Moir, 2010). Therapists, teacher and teacher aides were implementers in Houghton et al. (1998). Nurses, caregivers or other staff were implementers in seven studies (Chan et al., 2005 and Chan et al., 2007; Fava & Straus, 2010; Lotan, 2006a; Lotan et al., 2009; Merrick et al., 2004; Vlaskamp et al., 2003; Withers & Ensum, 1995). The implementer was not described in seven studies (Chan & Chien, 2017; Long & Haig, 1992; Shapiro et al., 1997; Sigal & Sigal, 2022; Singh et al., 2004; Thompson, 2011; Tunson & Candler, 2010). For four studies the implementer was a researcher or colleague (Cuvo et al., 2002; Martin et al., 1998; Toro, 2019) and for one (Koller et al., 2018) it was a Child Life Specialist. The MSE was located in a hospital for six studies (Ashby et al., 1995; Chan & Chien, 2017; Chan et al., 2007 and Chan et al., 2005; Kwok et al., 2003; Lindsay et al., 1997; Lindsay et al., 2001), a residential institution for twelve (Cuvo et al., 2001; Fava & Strauss, 2010; Long & Haig, 1992; Lotan, 2006a; Lotan, 2006b; Lotan et al., 2009; Merrick et al., 2004; Singh et al., 2004; Toro, 2019; Withers & Ensum, 1995; Vlaskamp et al., 2003) and at a school for three (Houghton et al., 1998; Thompson, 2011; Withers & Ensum, 1995). One study in a residential institution used a classroom with MSE equipment brought into the room for MSE sessions (Tunson & Candler, 2010). One was carried out in a dental practice where MSE equipment was dispersed throughout (Sigal & Sigal, 2022) and in one MSE equipment was taken to the child’s bedside (Koller et al., 2018).

The equipment used was designed to provide various forms of sensory stimulation. Most studies included equipment that provided visual effects such as bubble tubes, optic fibres, projectors, coloured lights and mirrors (e.g., Cuvo et al., 2001; Toro, 2019). Sound was frequently provided by various kinds of music and musical devices and in some studies through sound effects such as nature sounds (e.g., Martin et al., 1998; Singh et al., 2004). Smell was provided through aroma boards and aroma diffusers (e.g., Ashby et al., 1995; Chan et al., 2005). Tactile boards and vibrating equipment provided touch stimulation (e.g., Cuvo et al., 2001; Fava & Strauss, 2010). Some equipment could be operated by switches or press buttons (e.g., Chan et al., 2007; Houghton et al., 1998). Rooms were often dimly lit and contained soft padding, bean bags, water beds and/or mattresses (e.g., Kwok et al., 2003; Lotan et al., 2009).

Only six studies appear to have used the MSE with an implementer using a supportive and facilitative approach as in the original Snoezelen concept (Chan & Chien, 2017; Chan et al., 2005 and Chan et al., 2007; Cuvo et al., 2001; Fava & Strauss, 2010; Lotan et al., 2009). In other studies, it appeared someone other than the participants controlled the equipment or was actively teaching a behaviour rather than supporting choice and engagement (Ashby et al., 1995; Buono et al., 2022; Hong, 2004; Koller et al., 2018; Lotan, 2006a, 2006b; Moir, 2010). In Martin et al. (1998) the enabler provided a set amount of non-contingent attention (verbal chat) to each participant in both the MSE and comparison setting but does not appear to have supported MSE use. In two studies participants appeared to be passive (Toro, 2019; Withers & Ensum, 1995). In the remainder of the studies, it could not be determined how the room was being used or the roles of implementers.

Dependent Variables

A wide range of variables were measured which were collapsed into 14 categories, as well as an “other” category. Table 1 presents the category of variable used in each study organised by type of study design. The most frequently measured categories of variables were generic challenging behaviour and stereotypy which were each measured in nine studies. The least measured were the responsiveness category (one study) and the various “other” variables which were unique to the studies that included them.

Measurement

Along with the wide range of dependent variables examined were a wide range of measurement strategies ranging from structured observation systems, such as interval recording, through to anecdotal reports (see Table 3). Studies reporting only anecdotal data are not included in Table 2 (Hong, 2004; Kwok et al., 2003; one case in Lotan et al., 2006a). Performance on a task was used in three studies, rating or a checklist, based on direct observation was used in eight studies, a frequency count or rate was used in eight studies, interval recording was used in five studies, physiological measures, such as respiration and heart rate, were used in five studies, and a rating or checklist based on reports was used in six studies. Eighteen studies collected data in the MSE itself, three collected data before MSE use and 11 immediately after MSE use. Data were collected some time after MSE use in twelve studies.

Outcomes

Overall there were twice as many negative results reported (n = 32) than positive outcomes (n = 16) (Table 4). Table 1 presents dependent variable categories and reported outcomes. Clear cells indicate that positive outcomes were reported, while darker shaded cells indicate mixed results were reported and darkest cells indicate negative results. The lack of consistency in positive outcomes applies to measures made in the MSE, immediately after use and later on. There were also inconsistent results when behaviour in the MSE was compared to behaviour in other settings. It should also be noted that in some studies, interventions additional to the MSE were used, and the effects of these could not be separated from the effects of MSE use. Additional interventions included physiotherapy (Buono et al., 2022; Lotan, 2006a, b), massage (Lotan, 2006b; Lotan et al., 2009; Merrick et al., 2004) Moir (2010) actively taught switch use in all conditions except maintenance. Withers and Ensum (1995) included differential reinforcement of other behaviour to decrease challenging behaviour and Sigal and Sigal (2022) employed a range of practices aimed at decreasing patient anxiety, as well as MSE equipment distributed through the dental practice.

Given the poor quality of the reviewed research, the outcomes from higher quality studies are of most interest. The two single case experimental design studies reported by Cuvo et al. (2001) met the WWC quality standards. In the first study they found that for one participant stereotypy was lower in the MSE than in the living area, but there was no difference immediately afterwards. Two participants were more engaged in the MSE but there was no carry over to the living area afterwards. In the second study, for all participants when the MSE was compared to the living room and a walk outdoors, there was less stereotypy and SIB outdoors and participants were also more engaged when walking outdoors.

The better quality group designs were the randomised control trials reported by Chan and Chien (2017) and that reported by Chan et al. (2005, 2007). The only positive findings for MSEs was that participants were more relaxed and had improved emotional state immediately after MSE use (Chan et al., 2005, 2007) with no differences for the other nine categories of variables reported. In the other group design that scored 3/6, Singh et al. (2004) found less aggression in the MSE but no effects were apparent after MSE use. They also found less SIB in the MSE, with less SIB also apparent after MSE use. The differences were not large and no evaluation of the clinical effect was provided.

Discussion

The present review provided an examination of the use of MSEs for individuals with developmental disabilities without ASD. Primary concerns related to the quality of the research, how MSEs were used, outcome variables examined and state of evidence for MSE as an intervention.

Study Quality

Consistent with the conclusions in earlier reviews (Chan et al., 2010; Hogg et al., 2001; Lancioni et al., 2002; Lotan & Gold, 2009), the present analysis reveals little high quality evidence to support the use of MSEs with individuals with developmental disability. There is a preponderance of case studies and single group designs, from which definitive conclusions cannot be drawn. There were only two single case experimental design studies that met WWC quality criteria and the best of the randomised control trials only scored four out of a possible eight points for quality. As in earlier reviews we also found overall poor quality research designs, many with inadequate controls, subjective assessment measures, poorly defined dependent variables, lack of blinding of assessors, lack of observational and procedural reliability checks, and inappropriate analysis. It also appeared that positive results were more likely to be reported in studies with weak designs as noted by Hogg et al. (2001). When MSEs were compared to other settings, these were typically daily living environments, rather than other leisure options, which would have provided more appropriate comparison, given that they were often seen as a leisure option. There has also been little well-designed research that has explored the longer term impacts of MSE use, with only seven studies providing data on generalisation beyond the MSE room.

Use of MSEs

There was considerable variation in the way MSEs were used, in the number of sessions provided, length and the frequency of sessions and equipment used. For example, the number of sessions reported varied from one to 208 and the length of individual sessions varied from 10 min to an hour.

As already noted, the original concept for MSEs was as a leisure option to provide an enjoyable experience for the user, supported by an implementer to access preferred stimulation and there were to be no predetermined goals. Very few studies reported the role of implementers as being the supportive presence allowing participants to choose their experiences as described in early conceptualisations (Haggar & Hutchinson, 1991). Some researchers have emphasised the role of the enabler and the relationship of the enabler and user (Lotan & Gold, 2009; Martin et al., 1998; Lotan & Shapiro, 2005). Singh et al. (2004) and Vlaskamap et al. (2003) have suggested that equipment used in an MSE may need to be tailored to individual needs.

The present review revealed clear variation in purposes for which MSEs were used, reflecting they were conceptualised as leisure activity, served a rehabilitative function or some combination of the two. In addition, there were corresponding dissimilarities in the roles that support staff took as well as substantial variation in the dosage provided to participants. Taken together, this suggests that MSEs are not consistently conceptualised.

Outcomes Examined

Just as there was a wide range of reported uses for MSEs, there was considerable variation in the outcomes measured. These included relaxation, emotional state, and engagement as well as challenging behaviours and stereotypy. Other potential outcome measures included alertness, communication, social interaction, adaptive behaviour more generally and various physiological measures. While some studies were relatively targeted, many examined a wide range of outcomes in different categories (e.g., Long & Haig, 1992; Martine et al., 1998; Chan & Chien, 2017) without necessarily offering a clear conceptual rationale as to why change would be expected across the range of dependent variables examined. In addition, the question of what represents a desirable outcome may be open. For example, much of the research examines individuals with severe or profound intellectual disabilities, often in institutional residential settings. For such individuals, would relaxation, associated with lower arousal, necessarily be a desirable outcome? If the intention is to provide leisure activities, would outcomes reflecting relaxation or those reflecting engagement be appropriate, or what balance between these outcomes is apposite?

Some comment is also warranted in the approaches to outcome measurement. The use of objective measurement systems, such as counting the frequency of clearly and objectively defined behaviours or interval recording, were less common and there was more reliance on measures relying on subjective ratings or checklists, completed either from direct observation or based on reports. In some studies frequency counts were used for behaviours such as crying and shouting (e.g., Lotan et al., 2009; Moir, 2010) that are typically better measured in other ways (such as duration or interval recording). Some researchers used physiological measures such as pulse and respiration rate as a potentially more objective way of measuring relaxation. However, Koller et al. (2018), who used a range of physiological measures, concluded that such measures could not be reliably used to identify affective state because they could not determine which physiological measures related to observed affective states.

Effectiveness

Conclusions regarding the effectiveness of MSEs for individuals with developmental disabilities need to be qualified in terms of the poor quality of the corpus of research. In addition, the mixed findings across most classes of outcomes warrants attention.

The original conceptualisation of MSEs was as a leisure option for individuals with disabilities. If MSEs are a viable leisure option and if purported effects depend on relaxation, enjoyment and response to the stimuli in the MSE, it should be possible to demonstrate that participants enjoy using them, engage with the equipment and are relaxed during the session. Only one higher quality study (Chan et al., 2005; Chan et al., 2007) explored emotional state and relaxation, with positive results reported after use for emotional state, but no effect for relaxation. Engagement was measured in two higher quality studies (Cuvo et al., 2001), where participants appeared more engaged in the MSE than in the living area. In Experiment 2, however, Cuvo et al. reported that engagement was consistently higher during a walk outdoors than in the MSE. To support the use of an MSE as an engaging leisure option, studies would need to compare the MSE with an alternative leisure activity (as did Cuvo et al., 2001). It should also be noted that several studies reported individuals who appeared to dislike the MSE, appeared to be disengaged or non-responsive and refused to enter, or left the setting (e.g., Ashby et al., 1995; Fava & Strauss, 2010; Shapiro et al., 1997).

Thus, the available research provides no consistent support for the proposition that MSEs offer a leisure option for individuals with developmental disabilities, at least as reflected in measures related to relaxation, enjoyment or engagement. Further, there is a lack of evidence that MSEs are superior in any of these measures to more normalised leisure activities. It may be that MSEs do provide an enjoyable leisure experience for some people with developmental disabilities, particularly those living in institutions and those for whom access to regular environments may be difficult. Nasser et al. (2004) and Sachs and Nasser (2009) reported on family use of the MSE as a means of interacting with their child with intellectual disability in residential care in a shared activity, with most families reporting a positive experience. Some authors, however, have questioned the wisdom of investing in an expensive facility over providing other more normalised leisure activities with caregivers (Cuvo et al., 2001; Martin et al., 1998).

Going beyond simple provision of a leisure option, MSEs have been used to attempt to address challenging behaviour but, again, there was little consistent evidence to support this proposition. Overall, there were more negative than positive outcomes in each of the categories related to challenging behaviour in this review. Some researchers specifically suggested that the relaxation experienced in an MSE may ameliorate frustration or distress, and thus reduce problem behaviour, but reported results do not consistently support this claim (Chan & Chien, 2017; Chan et al., 2005; Singh et al., 2004). Possible effects on reducing stereotypic behaviour are attributed to the alternative forms of sensation provided by the MSE (e.g., Kwok et al., 2003; Shapiro et al., 1997), but again results were mixed and may depend on the function of the stereotypy and the degree of control participants have over the stimulation they receive.

A smaller number of studies provided examination of the expression or development if skills, such as adaptative behaviour, social interaction, and communication, with inconsistent results. As has been noted previously, evidence for generalisation outside the MSE room was examined in only seven studies. If the function of MSEs is anything beyond a purely leisure activity, demonstration of effects beyond the short period spent in the room would seem essential.

General Discussion

While research quality was poor in general and better quality studies tended to yield more negative results, there were nevertheless positive findings reported. When positive effects of MSE use are demonstrated, it may not be possible to identify what aspects of use may be causing those effects. As Cuvo et al. (2001) noted, staffing levels in the MSE may be higher and there may be more staff interaction than in daily living areas. Koller et al. (2018) also considered that interaction with facilitator may have been a factor in participant responses to MSEs. Novelty was offered by Houghton et al. (1998) as an alternative explanation for effects observed and Cuvo et al. (2001) also suggested that MSEs may be a novel experience, offering a change in regular routines. In addition, MSEs in some studies were used in combination with other interventions, such as physiotherapy, massage and differential reinforcement of other behaviour, so any impacts were confounded.

Weak research designs are sometimes employed in the early investigation of an intervention, where the focus is on evaluating feasibility or gaining a preliminary indication that the phenomena might be appropriate for more rigorous examination. We are well beyond this point with research on MSEs and low quality or exploratory studies should no longer be published. If further research on the impacts of MSE use is to be carried out, it needs to be well designed. Rather than the “shotgun” approach taken in many extant studies, where a wide array of variables are measured, sometimes without clear indications of the expected direction of change, a single or small number of a priori primary variables should be nominated. Ideally, these should be derived from a coherent and robust conceptual or theoretical framework and researchers should clearly nominate the expected direction of change. If other dependent variables are evaluated, they should be treated as secondary. Dependent variables need to be objectively defined and preference should be given to direct measures of relevant behaviour, rather than through rating scales, check lists and reports. Critically, it MSEs are advocated for more than leisure experiences, demonstration of behaviour change outside the limited MSE environment must be demonstrated with blinding of observers to condition. There needs to be much more clarity around how the equipment within the MSE is used and how participants are supported in their use. What may be more important is communication to schools and others contemplating installing MSEs that there is little or no high quality evidence of beneficial effects.

Conclusion

Commercial firms continue to promote MSEs and this may contribute to the on-going installation of MSEs in schools, institutions and other settings, despite the sparse evidence for beneficial effects. As identified in previous reviews, the research remains of poor quality and there is little consistency in the variables measured or the ways in which MSEs are used and limited research regarding long-term impacts. Even when considering the use of MSEs simply as a leisure option, there is little research that compares MSEs to more normalised leisure options. Overall, the use of MSEs with people with developmental disability cannot be recommended.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Ashby, M., Lindsay, W. R., Pitcaithly, D., Broxholme, S., & Geelen, N. (1995). Snoezelen: Its effects on concentration and responsiveness in people with profound multiple handicaps. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 58(7), 303–307. https://doi.org/10.1177/030802269505800711

Bergstrom, V. N. Z., O’Brien-Langer, A., & Marsh, R. (2019). Supporting children with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum disorder: Potential applications of a Snoezelen multisensory room. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, and Early Intervention, 12(1), 98–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/19411243.2018.1496869

Botts, B. H., Hershfeldt, P. A., & Christensen-Sandfort, R. J. (2008). Snoezelen: Empirical review of product representation. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 23(3), 138–147. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357608318949

Breslin, L., Guerra, N., Ganz, L., & Ervin, D. (2020). Clinical utility of multisensory environments for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A scoping review. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(4), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2020.037267

Buono, V. L., Torrisi, M., Leonardi, S., Pidalà, A., & Corallo, F. (2022). Multisensory stimulation and rehabilitation for disability improvement: Lessons from a case report. Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000031404

Cameron, A., Burns, O., Garner, A., Lau, S., Dixon, R., Pascoe, C., & Szafraniec, M. (2020). Making sense of multi-sensory environments: A scoping review. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 67(6), 630–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2019.1634247

Campbell, D. T., & Stanley, J. C. (1963). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research. Rand McNally.

Carter, M., & Stephenson, J. (2012). The use of multi-sensory environments in schools servicing children with severe disabilities. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 24, 95–109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-011-9257-x

Chan, J., & Chien, W. (2017). A randomised controlled trial on evaluation of the clinical efficacy of massage therapy in a multisensory environment for residents with severe and profound intellectual disabilities: A pilot study. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 61(6), 532–548. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12377

Chan, S. W., Chien, W. T., & To, M. Y. F. (2007). An evaluation of the clinical effectiveness of a multisensory therapy on individuals with learning disability. Hong Kong Medical Journal, 13(1), 28–31.

Chan, S., Fung, M. Y., Tong, C. W., & Thompson, D. (2005). The clinical effectiveness of a multisensory therapy on clients with developmental disability. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 26(2), 131–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2004.02.002

Chan, S., Thompson, D., Chau, J. P. C., Tam, W. W. S., Chiu, I., & W., S., & Lo, S. H. S. (2010). The effects of multisensory therapy in behaviour of adult clints with developmental disabilities - A systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 47(1), 108–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.08.004

Cuvo, A. J., May, M. E., & Post, T. M. (2001). Effects of living room, Snoezelen room, and outdoor activities on stereotypic behavior and engagement by adults with profound mental retardation. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 22(3), 183–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0891-4222(01)00067-1

Fava, L., & Strauss, K. (2010). Multi-sensory rooms: Comparing effects of the Snoezelen and the stimulus preference environment on the behavior of adults with profound mental retardation. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 31(1), 160–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2009.08.006

Haegele, J. A., & Porretta, D. L. (2014). Snoezelen multisensory environment: An overview of research and practical implications. Palaestra, 28(4), 29–32.

Haggar, L. E., & Hutchinson, R. B. (1991). Snoezelen: An approach to the provision of a leisure resource for people with profound and multiple handicaps. Mental Handicap, 19(2), 51–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3156.1991.tb00620.x

Hogg, J., Cavet, J., Lambe, L., & Smeddle, M. (2001). The use of ‘Snoezelen’ as multisensory stimulation with people with intellectual disabilities: A review of the research. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 22(5), 353–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0891-4222(01)00077-4

Hong, C. S. (2004). Helping children with learning disabilities. Making sense of multisensory environments. The Journal of Family. Health Care, 14(2), 35–38.

Houghton, S., Douglas, G., Brigg, J., Langsford, S., Powell, L., West, J., Chapman, A., & Kellner, R. (1998). An empirical evaluation of an interactive multi-sensory environment for children with disability. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 23(4), 267–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668259800033761

Hulsegge, J., & Verheul, A. (1987). Snoezelen, another world: A practical book of sensory experience environments for the mentally handicapped. ROMPA.

Kenyon, J., & Hong, C. S. (1998). An explorative study of the function of a multisensory environment. British Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation, 5(12), 619–623. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjtr.1998.5.12.14156

Koller, D., McPherson, A. C., Lockwood, I., Blain-Moraes, S., & Nolan, J. (2018). The impact of Snoezelen in pediatric complex continuing care: A pilot study. Journal of Pediatric Rehabilitation Medicine, 11(1), 31–41. https://doi.org/10.3233/PRM-150373

Kwok, H. W. M., To, Y. F., & Sung, H. F. (2003). The application of a multisensory Snoezelen room for people with learning disabilities—Hong Kong experience. Hong Kong Medical Journal, 9(2),122–126. Retrieved from https://www.hkmj.org/system/files/hkm0304p122.pdf

Lai, C. Y. (2003). The use of multisensory environments on children with disabilities: A literature review. International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation, 10(8), 358–363. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjtr.2003.10.8.13513

Lancioni, G. E., Cuvo, A. J., & O’Reilly, M. F. (2002). Snoezelen: An overview of research with people with developmental disabilities and dementia. Disability and Rehabilitation, 24(4), 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280110074911

Lancioni, G. E., Singh, N. N., O’Reilly, M. F., Oliva, D., Basili, G., & G. (2005). An overview of research on increasing indices of happiness of people with severe/profound intellectual and multiple disabilities. Disability and Rehabilitation, 27(3), 83–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280400007406

Leong, H. M., Carter, M., & Stephenson, J. R. (2015). Meta-analysis of research on sensory integration therapy for individuals with developmental and learning disabilities. Journal of Physical and Developmental Disabilities, 27(2), 183–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-014-9408-y

Lindsay, W. R., Black, E., Broxholme, S., Pitcaithly, D., & Hornsby, N. (2001). Effects of four therapy procedures on communication in people with profound intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 14(2), 110–119. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1468-3148.2001.00059.x

Lindsay, W. R., Pitcaithly, D., Geelen, N., Buntin, L., Broxholme, S., & Ashby, M. (1997). A comparison of the effects of four therapy procedures on concentration and responsiveness in people with profound learning disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 41(3), 201–207. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2788.1997.03535.x

Long, A. P., & Haig, L. (1992). How do clients benefit from Snoezelen? An exploratory study. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 55(3), 103–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308022692055003

Lotan, M. (2006a). Snoezelen and Down syndrome. Physical therapy intervention, theoretical background and case study. International Journal on Disability and Human Development, 5(4), 385–390. https://doi.org/10.1515/IJDHD.2006.5.4.385

Lotan, M. (2006b). Management of Rett syndrome in the controlled multisensory (Snoezelen) environment. A review with three case stories. The Scientific World Journal, 6, 791–807. https://doi.org/10.1100/tsw.2006.159

Lotan, M., & Gold, C. (2009). Meta-analysis of the effectiveness of individual intervention in the controlled multisensory environment (Snoezelen®) for individuals with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 34(3), 207–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668250903080106

Lotan, M., Gold, C., & Yalon-Chamovitz, S. (2009). Reducing challenging behavior through structured therapeutic intervention in the controlled multi-sensory environment (Snoezelen). Ten case studies. International Journal on Disability and Human Development, 8(4), 377–392. https://doi.org/10.1515/IJDHD.2009.8.4.377

Lotan, M., & Shapiro, M. (2005). Management of young children with Rett disorder in the controlled multi-sensory (Snoezelen) environment. Brain and Development, 27, S88–S94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.braindev.2005.03.021

Maggin, D. M., Cook, B. G., & Cook, L. (2018). Using single-case research designs to examine the effects of interventions in special education. Learning Disabilities Research and Practice, 33, 182–191. https://doi.org/10.1111/ldrp.12184

Martin, N. T., Gaffan, E. A., & Williams, T. (1998). Behavioural effects of long-term multi-sensory stimulation. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 37(1), 69–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8260.1998.tb01280.x

Merrick, J., Cahana, C., Lotan, M., Kandel, I., & Carmeli, E. (2004). Snoezelen or controlled multisensory stimulation. Treatment aspects from Israel. The Scientific World Journal, 4, 307–314. https://doi.org/10.1100/tsw.2004.30

Moir, L. (2010). Evaluating the effectiveness of different environments on the learning of switching skills in children with severe and profound multiple disabilities. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 73(10), 446–456. https://doi.org/10.4276/030802210X12865330218186

Nasser, K., Cahana, C., Kandel, I., Kessel, S., & Merrick, J. (2004). Snoezelen: Children with intellectual disability and working with the whole family. The Scientific World Journal, 4(1), 500–506. https://doi.org/10.1100/tsw.2004.105

Pagliano, P. (1998). The multi-sensory environment: An open-minded space. British Journal of Visual Impairment, 16(3), 105–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/026461969801600305

Pagliano, P. (2006). The multisensory environment: Providing a feeling of emotional closeness. Journal of the South Pacific Educators in Vision Impairment, 3, 23–32.

Performance Health. (2023). How to create a multisensory room. Retrieved 24 August, 2023, from https://www.performancehealth.com/articles/how-to-create-a-multi-sensory-room-the-full-experience

Proff, I., Williams, G. L., Quadt, L., & Garfinkel, S. N. (2022). Sensory processing in autism across exteroceptive and interoceptive domains. Psychology & Neuroscience, 15(2), 105–130. https://doi.org/10.1037/pne0000262

Rhino Sensory UK Ltd. (2023). Designing and installing multi-sensory rooms for education. Retrieved 24 August, 2023, from https://www.rhinouk.com/sector/education/

Robertson, C. E., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2017). Sensory perception in autism. Nature Reviews: Neuroscience, 18(11), 671–684. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn.2017.112

Rompa (2023). What is a Snoezelen® sensory room. Retrieved 1 September, 2023, from https://www.rompa.com/interactive-sensory-room

Sachs, D., & Nasser, K. (2009). Facilitating family occupations: Family member perceptions of a specialized environment for children with mental retardation. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 63(4), 453–462. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.63.4.453

Shapiro, M., Parush, S., Green, M., & Roth, D. (1997). The efficacy of the “Snoezelen” in the management of children with mental retardation who exhibit maladaptive behaviours. The British Journal of Development Disabilities, 43(85), 140–155. https://doi.org/10.1179/bjdd.1997.014

Sigal, A., & Sigal, M. (2022). The multisensory/Snoezelen environment to optimize the dental care patient experience. Dental Clinics, 66(2), 209–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cden.2021.12.001

Singh, N. N., Lancioni, G. E., Winton, A. S. W., Molina, E. J., Sage, M., Brown, S., & Groeneweg, J. (2004). Effects of Snoezelen room, activities of daily living skills training, and vocational skills training on aggression and self-injury by adults with mental retardation and mental illness. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 25(3), 285–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2003.08.003

TFH. (2023). Our latest rooms. Retrieved October 16, 2023, from https://multisensoryenvironments.com/en-US

Thompson, C. J. (2011). Multi-sensory intervention observational research. International Journal of Special Education, 26(1), 202–214.

Toro, B. (2019). Memory and standing balance after multisensory stimulation in a Snoezelen room in people with moderate learning disabilities. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 47(4), 270–278. https://doi.org/10.1111/bld.12289

Tunson, J. N., & Candler, C. (2010). Behavioral states of children with severe disabilities in the multisensory environment. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 30(2), 101–110. https://doi.org/10.3109/01942630903546651

Vlaskamp, C., De Geeter, K. I., Huijsmans, L. M., & Smit, I. H. (2003). Passive activities: The effectiveness of multisensory environments on the level of activity of individuals with profound multiple disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 16(2), 135–143. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1468-3148.2003.00156.x

What Works Clearinghouse. (2022). What Works Clearinghouse procedures and standards handbook. Version 5.0.. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance. Available from https://iees.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/Handbooks

Withers, P. S., & Ensum, I. (1995). Successful treatment of severe self injury incorporating the use of DRO, a Snoezelen room and orientation cues: A case report. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 23(4), 164–167. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3156.1995.tb00189

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors contributed to study conception and design. Searches were conducted by Jennifer Stephenson. Identification of articles for inclusion, data coding and extraction were carried out by both authors. The first draft was written by Jennifer Stephenson and Mark Carter critically revised the draft. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Both authors contributed to study conception and design. Searches were conducted by Jennifer Stephenson. Identification of articles for inclusion, data coding and extraction were carried out by both authors. The first draft was written by Jennifer Stephenson and Mark Carter critically revised the draft. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent to Publish

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Stephenson, J., Carter, M. The Use of Multisensory Environments with Individuals with Developmental Disabilities: A Systematic Review. J Dev Phys Disabil (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-024-09982-4

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-024-09982-4