Abstract

Parenting is a rewarding experience but is not without its challenges. Parents of Autistic children face additional challenges, and as a result can experience lower levels of wellbeing and more mental health problems (i.e., depression, anxiety, stress). Previous studies have identified concurrent correlates of wellbeing and mental health. However, few have investigated predictors of subsequent wellbeing and mental health, or of change over time, among parents of pre-school aged autistic children. We examined child-, parent-, and family/sociodemographic factors associated with change in parents’ mental health and wellbeing across three timepoints (spanning approximately one year) among 53 parents of Autistic pre-schoolers (M = 35.48, SD = 6.36 months. At each timepoint, parents reported lower wellbeing and greater mental health difficulties compared to normative data. There was no significant group-level change over time in parent outcomes. However, individual variability in short-term (~ 5 months) wellbeing and mental health change was predicted by a combination of child- and parent-related factors, while variability in medium-term (~ 10 months) change was predicted by parent factors alone. Parents’ description of their child and their relationship predicted change in both wellbeing and mental health. Furthermore, participating in a parent-mediated intervention (available to a subgroup) was a significant predictor of change in wellbeing. Our findings highlight potentially modifiable factors (e.g., learning healthier coping strategies) that may positively impact both short- and medium-term change in parental outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

While raising an Autistic child can be rewarding (Potter, 2016), many parents experience more mental health difficulties (i.e., chronic stress, anxiety, and depression) and lower wellbeing (i.e., life satisfaction, autonomy, purpose, connectedness to people, balance of positive and negative emotions) than parents of non-Autistic children (Green et al., 2021; Salomone et al., 2018; Schnabel et al., 2020). This may be particularly evident during early childhood, where parents have reported increasing levels of parenting-related stress following their child’s diagnosis (Green, 2024). In an adaptation of Belsky’s (1984) model of parenting, it has been posited that a combination of parent characteristics, child characteristics, and family social environment impact parenting in early childhood (Taraban & Shaw, 2018). Among families of young Autistic children, additional parenting responsibilities and challenges further add to complexity of parenting in early childhood. In particular, stigma (den Houting et al., 2021; Smith et al., 2023) and inadequate access to quality resources (Smith et al., 2023) may further contribute to parenting stress, in line with minority stress theory (Meyer, 2003), which takes into account the added stressors experienced by individuals from minority groups and communities, including the Autism community (Gunty, 2021). This may be especially true in Australia; despite an increasing need for supports following diagnosis, there has not been a proportionate increase in services, leaving many families struggling to cope, particularly marginalised families (Australian Government, 2023; Commonwealth of Australia, 2023; Smith et al., 2023). These added stressors and unique circumstances may be at least partially contributing to mental health challenges and lower wellbeing in parents of young Autistic children.

Individual differences in mental health and wellbeing in parents of Autistic children have been linked to a broad range of factors. Some such factors relate to characteristics of parents, including use of coping strategies (Benson, 2014), social supports (Benson, 2020), and mindfulness (Cheung et al., 2019; Green et al., 2021), as well as their personality (Green et al., 2021) and autistic traits (Ingersoll & Hambrick, 2011; Pruitt et al., 2018). Other factors associated with parent wellbeing and mental health challenges relate to child characteristics, including autistic presentation (Green et al., 2021; Ingersoll & Hambrick, 2011; Mathew et al., 2019) and emotional and behaviour problems (Cheung et al., 2019; Pruitt et al., 2018; Salomone et al., 2018; Smith et al., 2021), as well as the parent–child relationship quality (Hastings et al., 2006). In addition, socioeconomic status and cultural background have also been shown to correlate with parental mental health and wellbeing (Mathew et al., 2019).

What remains unclear is how the aforementioned factors may be differentially associated with parental mental health versus wellbeing, and their relative predictive value. Mental health challenges and wellbeing have been presumed to represent opposite ends of the same construct (Kinderman et al., 2015). However, it is increasingly clear that mental health and wellbeing are related yet distinct constructs, with unique determinants (Cai et al., 2020; Green et al., 2021; Kinderman et al., 2015; Patalay & Fitzsimons, 2016; Salomone et al., 2018). For example, amongst parents of school-aged Autistic children, mental health challenges have been shown to be concurrently associated with measures of child factors (i.e., reduced daily living skills, cognitive impairment, and greater emotional and behavioural problems), parent factors (i.e., higher education level), and family sociodemographic factors (i.e., lower household income), whereas wellbeing was associated with child characteristics alone (i.e., fewer emotional and behavioural problems) (Salomone et al., 2018). However, among parents of Autistic pre-schoolers, a different pattern of characteristics associated with concurrent parental mental health and wellbeing has been identified (Green et al., 2021). Specifically, mental health difficulties were predicted by a combination of child- (i.e., parent-reported autism traits) and parent characteristics (i.e., trait negative emotionality), with wellbeing predicted by parent factors alone (i.e., trait extraversion/sociability, mindfulness, and mental health) (Green et al., 2021). Although the specific predictors of mental health challenges and wellbeing were different across these two studies (Green et al., 2021; Salomone et al., 2018), mental health challenges were consistently shown to be influenced by a broader range of factors compared to wellbeing.

While there is growing evidence that mental health and wellbeing have unique determinants among parents of Autistic children (Cai et al., 2020; Green et al., 2021; Salomone et al., 2018), the cross-sectional design of existing work limits the inferences that can be drawn, and longitudinal studies have to date largely focused on parents of Autistic school-aged and adolescent children. Less work is dedicated to parents of younger, more recently-diagnosed children who may be particularly vulnerable to mental health and wellbeing impacts (Hickey et al., 2021). Parent-mediated interventions that focus on child outcomes have been suggested as indirect avenue to support parental mental health and wellbeing during early childhood (Estes et al., 2019). However, the evidence for parental benefits from these interventions is less substantial than for children (see Green, 2024; Leadbitter et al., 2018; Oono et al., 2013). For example, Green (2024) recently found that Autistic pre-schoolers made substantial developmental gains regardless of the type of support they received, and that additional parent-mediated intervention did not improve child or parent outcomes. However, it was suggested that using alternative methods of analysis, such as the reliable change index (RCI; Jacobson & Truax, 1992), may be a psychometrically reliable way of measuring individual-level change, compared to other methods used to assess group mean-level change over time.

The Current Study

Operating within the framework of Taraban and Shaw’s (2018) model of parenting, we examined which, among a range of child, parent, and family/socioeconomic factors, predicted change over time in self-reported mental health and wellbeing in a sample of parents of Autistic pre-schoolers, accessing community group/centre-based and/or parent-mediated supports. Based on past work, we hypothesised that baseline parent measures (i.e., mindfulness, coping strategies, and social supports), child features (i.e., autistic presentation, emotional and behavioural problems), parent–child relationship quality, and family/socioeconomic factors (i.e., income, cultural background) would predict change (i.e., RCI z-scores) in both parental mental health and wellbeing. We were particularly interested to see whether there would be common or unique predictors of change in parental mental health challenges and wellbeing, making no particular predictions given the limited amount of comparative research within this age range. As parent-mediated supports have been suggested to benefit parent mental health and wellbeing (Leadbitter et al., 2018; Oono et al., 2013), we further hypothesised that participation in this particular approach (vs. centre/group-based supports) might also evidence benefits.

Method

Participants and Procedure

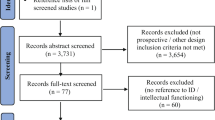

Parent–child dyads (N = 53) participated in a broader evaluation of Autistic children’s outcomes following early intervention; engagement with community-based service providers (n = 17) or a university co-located early intervention service (n = 36). Study eligibility criteria have been previously reported (see Green, 2024; Smith et al., 2021, 2022). Briefly, children were aged 17–43 months with a confirmed Autism diagnosis, and no parent had significant and unmanaged depression or anxiety such that the demands of study participation might exacerbate their condition.

The data presented here were obtained at three timepoints (Fig. 1): study intake (Time 1; T1), and approximately 5- (T2) and 10 months (T3) later. A subset of families (n = 18), selected at random, were offered parent-mediated support—specifically parent delivered early start denver model (P-ESDM; Rogers et al., 2012)—between their T2 and T3 assessments, as an adjunct to their other group/centre-based service enrolment ESDM program (Rogers & Dawson, 2010; Vivanti et al., 2017, 2019) between T1 and T3. Ethics approval was obtained from La Trobe University (HREC # 16–136). Parents provided informed consent for their own and their child’s research participation.

Measures

Parent and Family Context Characteristics

The Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995) was completed at each timepoint to measure mental health challenges. The DASS-21 is a 21-item questionnaire, with items rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale (0 = Did not apply to me at all; 3 = Applied to me very much, or most of the time). Items are negatively worded (e.g., I find it hard to wind down); higher scores indicate more challenges across three subscales measuring depression, anxiety, and stress. Total scores were used in analyses (range 0–120). The DASS-21 has a more robust factor structure than the DASS, and high reliability and convergent validity with other comparable measures (Henry & Crawford, 2005).

The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing scale (WEMWBS; Tennant et al., 2007a, 2007b) was completed at each timepoint to measure wellbeing. The WEMWBS is a 14-item questionnaire measuring subjective and psychological components of wellbeing. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = None of the time; 5 = All of the time). Items are positively worded (e.g., “I’ve been feeling optimistic about the future); higher scores indicate greater wellbeing. Total scores were used in analyses (range 14–70). The WEMWBS has good validity and high reliability (Tennant et al., 2007a, 2007b) and is sensitive to change across populations and in diverse public health interventions and programs (Stewart-Brown et al., 2011).

The Clarke modification of the Holroyd Questionnaire on Resources and Stress (CQRS; Konstantareas et al., 1992) was used to measure parenting-related stress and resources at T1. The CQRS was designed for use with families with children with neurodevelopmental conditions. The CQRS comprises 78 items rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale (1 = Strong agreement with statement; 4 = Strong disagreement with statement). Statements are worded either positively (e.g., “Our relatives have been helpful”) or negatively (e.g., “I have too much responsibility”); higher scores reflect more parenting stress and fewer resources. Mean scores were used in analyses (range 1–4). The CQRS has good internal consistency, split-half reliability, and coefficient of stability, as well as acceptable construct and concurrent validities (Konstantareas et al., 1992).

The Brief COPE Scale (Carver, 1997) was used to measure coping strategies at T1. It comprises 28 items rated on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = I haven’t been doing this at all; 4 = I’ve been doing this a lot). Scores for two overarching coping styles (Carver et al., 1989) were computed—avoidant (e.g., self-distraction, denial, venting) and approach coping (e.g., emotional support, positive reframing, acceptance)—with higher scores reflecting more behaviours indicative of each coping style. The Brief COPE has been shown to have adequate factor structure (Carver, 1997) and has been used in parents of Autistic children (Benson, 2010, 2014).

The Autism-Specific Five-Minute Speech Sample (AFMSS; Benson et al., 2011) provided a measure of the quality of the parent–child relationship at T1, through the coding of indicators of expressed emotion (EE) from a five-minute speech recording of each parent’s description of their child and their relationship. Parental EE is comprised of six subcomponents, including four categorical codes: initial statement, warmth, relationship, and emotional over-involvement (EOI), rated as either positive/neutral/negative or high/moderate/low. The final two subcomponents are critical comments and positive comments, both scored as a frequency counts. EE subcomponent ratings were used in analyses. (for more details see Smith et al., 2021). The AFMSS has been shown to have good validity and reliability (Benson et al., 2011) and has been used in parents of pre-school aged children (Smith et al., 2021).

The Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS; Brown & Ryan, 2003) was used to measure mindfulness at T1. The MAAS consists of 15 items (e.g., “I could be experiencing some emotion and not be conscious of it until some time later.”) rated on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = Almost always; 6 = Almost never). The mean score was used for analyses, with higher scores indicating greater levels of mindfulness. The MAAS has good reliability and validity (Brown & Ryan, 2003), including in parents of Autistic children (Rayan & Ahmad, 2018).

The Autism Spectrum Quotient – 10 (AQ-10; Allison et al., 2012) provided a measure of parental autism traits at T1. The AQ-10 comprises 10 items (e.g., “I find it easy to ‘read between the lines’ when someone is talking to me.”) rated on a 4-point Likert scale (Definitely agree to definitely disagree). The total score was used in analyses, with higher scores reflecting more autism traits. The AQ-10 has high reliability and validity (Allison et al., 2012).

Sociodemographic information was collected for each family, including education level, household income, the primary language spoken at home, culturally and/or linguistically diverse (CALD) status, and number of children in the family (both Autistic/non-Autistic). Categorical sociodemographic variables (i.e., education, household income, siblings) were dichotomised for analyses. Some data collection occurred following onset of the COVID-19 worldwide pandemic, during which the local region experienced multiple, protracted periods of lockdown (i.e., stay-at-home order) which have been have been linked to poorer wellbeing and increased depression (Hedley et al., 2021). The effect of data collection before and during the pandemic was therefore also considered, by comparison of parent outcomes pre- and post-lockdown. Parent and family characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Child Characteristics

The MSEL (Mullen, 1995) was used to assess children’s developmental/cognitive skills, and is a standardised assessment of verbal (Receptive and expressive language) and non-verbal (Fine motor and visual reception) abilities. A developmental quotient (DQ) was computed for analysis (i.e., age equivalent average/chronological age × 100), with scores at or near 100 reflecting skills near chronological age expectations. The MSEL has good internal reliability and strong test–retest and inter-scorer reliability (Mullen, 1995), as well as construct, convergent, and divergent validity (Swineford et al., 2015).

The ADOS-2 (Lord et al., 2012) was used to confirm diagnosis and assess level of autism traits, and was administered by research-reliable assessors. The modules used within the current study included the Toddler Module (for children aged 12–30 months), Module 1 (for children aged 31 months and older with no/limited speech), and Module 2 (for children using phrase speech). Calibrated Severity Scores (CSS; Esler et al., 2015; range 1–10) were calculated for analysis, with higher scores reflecting greater severity. The CSS has shown strong test re-test reliability across all modules (ICC = 0.71–0.89, p < 0.05) (Janvier et al., 2022).

The Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ; Rutter et al., 2003) was used as a parent-report measure of child autism traits. The SCQ is a 40-item questionnaire yielding scores ranging from 0 to 39, with higher total scores again reflecting higher levels of autism traits. The SCQ has high sensitivity and specificity (Chandler et al., 2007; Rutter et al., 2003).

The Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales 2nd Edition (VABS-II; Sparrow et al., 2005) was administered via parent interview to measure adaptive skills. The VABS-II measures adaptive behaviour across four domains: communication, daily living skills, socialisation, and motor skills. The Adaptive Behavior Composite (ABC) standard score (population M = 100; SD = 15) was computed for analysis, with higher scores reflecting greater adaptive behaviour abilities. The VABS-II has strong internal consistency, test–retest reliability, inter-interviewer reliability, and validity (Sparrow et al., 2005).

The preschool version of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000) was used as a parent-report measure of behavioural (externalising) and emotional (internalising) difficulties. The CBCL comprises 113 questions rated on a 3-point Likert scale (0 = Absent; 2 = Occurs often). Higher scores for each indicating greater difficulties. The CBCL has adequate sensitivity (0.66) and strong specificity (0.83) (Warnick et al., 2008).

Parent-Mediated Intervention

ESDM is a developmental-behavioural intervention that targets children’s social, cognitive, and language skills across various delivery formats (e.g., individual, group- and parent-coaching methods; Estes et al., 2014; Rogers & Dawson, 2010; Vivanti et al., 2017). For families offered P-ESDM, this comprised up to 13 1-h weekly clinic-based sessions: an initial child assessment and goal-setting session with parent and coach, and 12 sessions during which staff provided hands-on direct coaching of parents’ ESDM strategy use.

Statistical Procedure

Change in Mental Health Challenges and Wellbeing

The presentation of and change in parents’ DASS-21 and WEMWBS total scores were characterised in three ways. First, group mean-level change across T1-T3 was examined using one-way repeated measures ANOVA. Second, DASS-21 and WEMWBS total scores for this sample were compared to normative levels using t-tests (including Australian-based norms for DASS-21, and UK-based norms for WEMWBS [as recommended by Taggart et al. (2016)]). Third, RCI z-scores (Jacobson & Truax, 1992) were computed as indicators of psychometrically reliable individual-level change, for each of DASS-21 and WEMWBS scores from T1-T2 and T1-T3.

Predictors of Change in Mental Health and Wellbeing

Candidate parent-, child-, and family-related predictors of DASS-21 and WEMWBS RCI z-scores were identified through initial correlations, t-tests, and ANOVAs (see Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). After applying the Benjamini-Hochberg (False Discovery Rate [FDR]) correction, initial significant findings were no longer present. This correction may be too stringent, and given that the effect sizes indicate small to medium effects (Ferguson, 2016), analyses proceeded without correction for multiple comparisons. Where multiple candidate predictors were initially identified, those most strongly associated with the given outcome (i.e., showed small to medium effect sizes) were retained for subsequent regression analyses, with a maximum of four potential predictors (i.e., one per 10 participant cases; (Hollestein et al., 2021)).

Results

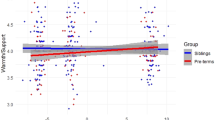

As shown in Fig. 2 there was no significant group mean-level change over time in WEMWBS [F(2.00, 76.00) = 1.112, p = 0.334, ω2 = 0.000], or DASS-21 total scores [F(2.00, 78.00) = 0.960, p = 0.387, ω2 = 0.000]. Parents in this sample consistently reported lower wellbeing and higher mental health difficulty levels than normative data (Table 2).Approximately one-third of parents reported above ‘normal’ levels of depression, anxiety, and stress, with around 10% reporting severe or extremely severe levels (Fig. 3).

Descriptive data for parental wellbeing and mental health outcomes (T1-2 and T1-3 RCI z-scores) are presented in Table 3. While substantial individual variation was evident, the vast majority of parents were categorised as showing no reliable change over time on either measure (i.e., −1.96 < z < 1.96). Descriptive data for other T1 parent and child measures—candidate predictors of parental outcomes—are presented in Table 4.

Predictors of Change in Wellbeing and Mental Health

Results from the regression models are presented in Table 5. All assumptions for regression analyses were met. In the prediction of WEMWBS T1-T2 RCI z-scores, the overall model was significant, with DASS-21 total score, CQRS family sharing, and VABS ABC SS entered as predictors together accounting for 22% of the variance. Among these, however, only VABS ABS SS was a significant unique predictor, accounting for 9% of the variance. In the model predicting T1-T3 WEMWBS RCI z-scores, the three candidate predictors (given n = 39) with strongest magnitude of effects were selected for inclusion. Together, DASS-21 total score, P-ESDM participation, and AFMSS initial statement accounted for 38% of the variance, with only P-ESDM participation making a significant unique contribution, accounting for 16% of variance (but noting a non-significant trend for contribution of DASS-21 score; p = 0.058).

For the model predicting T1-T2 DASS-21 RCI z-scores, 23% of variance was accounted for by ADOS CSS, Brief COPE avoidant coping, and AFMSS initial statement. However, no predictor made a significant unique contribution. For T1-T3 DASS-21 RCI scores, AFMSS initial statement was the only factor with a significant bivariate association, and entered into a regression model, accounted for 16% of the variance.

Discussion

Many parents describe raising an Autistic child as a rewarding experience (Potter, 2016). However, arising challenges may substantially impact mental health and wellbeing (Schnabel et al., 2020). We found no mean-level group change in the mental health difficulties or wellbeing of parents of young Autistic pre-schoolers over a one-year period of accessing community-based early intervention services. However, substantial variability was evident with RCI z-scores for a small subgroup of parents indicative of ‘reliable’ change over our follow-up period.

Predictors of Short-Term and Medium-Term Change in Wellbeing and Mental Health

Our hypothesis, that baseline parent-, child-, and family factors would predict change in parental mental health and wellbeing outcomes, was partially supported. After applying an FDR correction, the associations between baseline predictive factors and parent outcomes were no longer statistically significant; therefore, results from the regression analyses should be interpreted conservatively as trends given the increased chance of Type 1 error.

Results from regression analyses suggested that a combination of parent, child, and family/socioeconomic factors may predict change in parental wellbeing and mental health, consistent with Taraban and Shaw’s (2018) model of parenting. Parental coping strategies, specifically avoidant coping, were associated with short-term (T1-T2), but not medium-term (T1-T3), change in mental health challenges. These findings are consistent with past research demonstrating the importance of coping strategies to parental mental health and wellbeing (Benson, 2014; Cai et al., 2020; Dabrowska & Pisula, 2010; Zablotsky et al., 2013). Cai et al. (2020) found that avoidant coping strategies predicted anxiety and depression in mothers of young school-aged Autistic children, while problem-focused (approach) coping strategies predicted wellbeing. Cai et al.’s findings also highlight how mental health and wellbeing are related yet distinct constructs, with unique predictors. We also found that baseline measures of parent mental health challenges were associated with both short-term and medium-term change in wellbeing. This finding is consistent with past research demonstrating that concurrent measures of mental health predicted wellbeing, but not vice versa, among parents of Autistic pre-schoolers (Green et al., 2021).

Child factors were only associated with short-term, not medium-term, change in parent wellbeing and mental health outcomes. Parent ratings of children’s adaptive behaviour were associated with short-term change in parental wellbeing, while researcher ratings of child autism traits were associated with short-term change in parental mental health. Findings from past research examining the link between child characteristics and parent outcomes have been mixed. While adaptive behaviours have been associated with concurrent measures of parenting self-efficacy (Taylor et al., 2021) and sense of competence (Mathew et al., 2019), there has been little (Leadbitter et al., 2018) to no evidence (Green et al., 2021; Taylor et al., 2021) that adaptive behaviours have been directly linked to parent wellbeing. Two recent studies measured wellbeing using the WEMWBS in parents of Autistic children found no association between child adaptive behaviours and concurrent levels of parent wellbeing (Green et al., 2021; Taylor et al., 2021). It is therefore possible that while adaptive behaviour may not be associated with concurrent levels of wellbeing, it may be associated with change in wellbeing. Alternatively, methodological differences may account for conflicting findings between studies, as associations between adaptive behaviour and parent wellbeing have been found when using the recently-developed Autism Family Experience Questionnaire (AFEQ; Leadbitter et al., 2018). Some evidence suggests that adaptive behaviour may have been associated with concurrent parent mental health challenges in middle childhood (Salomone et al., 2018) but not during the pre-school years (Green et al., 2021). A study examining change in parenting stress in caregivers of Autistic pre-schoolers found that adaptive behaviour was predictive of change in parenting stress above and beyond cognitive skills, level of autism traits, and problem behaviour (Green & Carter, 2014). The current study examined changed in mental health challenges broadly, rather than its separate components (i.e., depression, anxiety, and stress); it is therefore possible that while we found no association between adaptive behaviour and mental health challenges, there may have been an association with parenting-related stress. Similarly, past findings regarding associations between child autism traits and parent outcomes have been mixed. Interestingly, researcher ratings of child autism traits have not been associated with concurrent measures of parent wellbeing or mental health (Green et al., 2021; Salomone et al., 2018); however, we have previously found that parent ratings of child autism traits were associated with concurrent levels of parent mental health, but not wellbeing, in a similar cohort (with some participants overlapping in the current sample) of parents of Autistic pre-schoolers (Green et al., 2021). The findings from the current study were therefore somewhat unexpected, in that researcher ratings, and not parent-ratings, of autism traits predicted short-term change in mental health. These findings draw attention to the differences that can occur due to the timing of measurements; however, caution should be taken in interpretation given the sample size.

The parent–child relationship, as measured by the AFMSS, was the only shared predictor of change in both wellbeing and mental health challenges. The AFMSS initial statement score reflects whether the first comment a parent makes about their child in response to a standard probe about their relationship is positive vs. neutral or negative (Benson et al., 2011). Here, this was predictive of variation in both short- and medium-term mental health change, and medium-term wellbeing change. That is, parents with subsequently positive shifts in mental health and wellbeing outcomes were more likely to have offered an initial positive or neutral (vs. negative) initial statement about their child, 5- to 10-months earlier. Research examining the predictive value of AFMSS ratings of parent–child relationship quality and parental mental health or wellbeing outcomes is limited, with sub-codes such as the Initial Statement rarely considered (Benson et al., 2011). The AFMSS was developed from the FMSS, which has evidence of robust association with mental health problems among parents of children with other conditions (Hastings et al., 2006). These findings signal the potential value of future research investigating current parent–child relationship quality as a potential indicator of future parent outcomes.

Among family/socioeconomic factors, only family support, as measured by the CQRS, was associated with short-term change in parental wellbeing. In families with Autistic children, family support networks have been shown to impact mental health (Bromley et al., 2004) and wellbeing (Ekas et al., 2010), and spousal support in particular has been shown to predict marital quality (Benson, 2020). Benson (2012) found that among mothers of Autistic children, the size and function (i.e., emotional support) of support networks predicted increased levels of perceived support, which predicted lower levels of depression and higher levels of wellbeing. Furthermore, received spousal support has been shown to indirectly effect marital quality, via perceived spousal support, only when child problem (externalising) behavious were at low or moderate levels, and not high (Benson, 2020). Benson’s (2020) findings suggest that spousal support may be most effective under less stressful parenting conditions. Together, these findings suggest the importance of support, particularly emotional support from family and significant others, for parents of Autistic children.

Finally, the potential impact of parent-mediated intervention on parental wellbeing and mental health was examined. Access to adjunctive parent-mediated intervention (between T2-T3) was associated with change in wellbeing outcomes immediately post-intervention (spanning T1-T3 follow-up). While several studies have reported benefits of parent-mediated intervention for parental wellbeing (Leadbitter et al., 2018; Palmer et al., 2020) and specific benefits of P-ESDM for stress (Estes et al., 2014) other studies have found no such effects (Green, 2024; Zhou et al., 2018). Mixed findings in the literature may be due to differences in study design, measurement, or analytic approach, or variation in participant/sample characteristics. Differential impacts for parent mental health and/or wellbeing may also be anticipated as a function of variation in the theoretical foundation, target outcomes, and/or delivery method of different parent-mediated interventions (Trembath et al., 2023).

Taken together, our findings highlight the potential influence that parent, child, and family factors may have on wellbeing and mental health in parents of Autistic children, in line with Taraban and Shaw’s (2018) adaptation of Belsky’s (1984) model of parenting. Furthermore, while our findings may be potentially contingent on specific test–retest intervals, they also highlight the importance of timely parent supports (e.g., coping strategies, social support networks), soon after diagnosis.

The primary limitation of this preliminary study is small sample size. Nevertheless, large effect sizes for observed associations (e.g., d = 0.79 for differential wellbeing outcomes from access to parent-mediated intervention group vs. rest of sample) suggests our reported results are robust. Furthermore, after correcting for multiple comparisons, initial associations between baseline predictor variables and parent outcomes were no longer significant, and hence results from the regression analyses should be considered with appropriate caution. Future larger studies are warranted to corroborate these, as well as potential genuine smaller effects that we might have been underpowered to identify, as well as test for potential moderating (e.g., parent–child relationship) and/or mediating (e.g., P-ESDM) effects. Exclusion criteria for the larger evaluation precluded the involvement of parents with significant unmanaged depression or anxiety, which may limit the generalisability of our findings. However, the factors included in our regression models all had moderate to strong bivariate associations with outcomes, so this exclusion on important ethical grounds unlikely substantially impacted our findings. The small number of fathers in the study impacts on the generalisability, and future studies may wish to consider targeted recruitment strategies to engage fathers.

Future investigation is also required to better understand the link between change in parental outcomes as a function of the parent–child relationship, indexed here by parent initial statement when describing their child. Perhaps most promising, our findings point toward potentially modifiable factors—engagement of coping strategies, access to informal social- and formal parent-mediated support services—that may be harnessed for the future benefit of parents of young Autistic children.

Conclusion

Parents of Autistic pre-schoolers experienced lower levels of wellbeing and higher levels of mental health challenges compared to population norms in the period following their child’s diagnosis. However, a combination of parent, child, and family factors may predict change in wellbeing and mental health challenges. These findings are in line with Taraban and Shaw’s (2018) adaptation of Belsky’s (1984) model of parenting, suggesting that a complex interplay of factors impact on parental wellbeing and mental health. For clinicians working with families of Autistic children, our findings highlight the importance of initial parental mental health challenges, the quality of the parent–child relationship, and timely parental supports (e.g., developing coping strategies, support from family) for parents’ wellbeing and mental health following their child’s diagnosis.

Competing Interests

Authors (CG, JS, CB, LC, KH) have previously received salary from grant funding to conduct research associated with the clinical provider of early intervention that participants were enrolled in, and thus held prior affiliations with this clinical provider.

References

Achenbach T., Rescorla L. (2000). Child Behavior Checklist.

Allison, C., Auyeung, B., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2012). Toward brief “red flags” for autism screening: the short autism spectrum quotient and the short quantitative checklist in 1,000 cases and 3,000 controls. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 51(2), 202–212.

Australian Government. (2023). What we have heard: moving towards development of a National Autism Strategy. Australia

Belsky, J. (1984). The determinants of parenting: A Process Model. Child Development, 55(1), 83–96. https://doi.org/10.2307/1129836

Benson, P. R. (2010). Coping, distress, and well-being in mothers of children with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4(2), 217–228.

Benson, P. R. (2012). Network characteristics, perceived social support, and psychological adjustment in mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42, 2597–2610.

Benson, P. R. (2014). Coping and psychological adjustment among mothers of children with ASD: An accelerated longitudinal study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(8), 1793–1807.

Benson, P. R. (2020). Examining the links between received network support and marital quality among mothers of children with ASD: A longitudinal mediation analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(3), 960–975.

Benson, P. R., Daley, D., Karlof, K. L., & Robison, D. (2011). Assessing expressed emotion in mothers of children with autism: The Autism-Specific Five Minute Speech Sample. Autism, 15(1), 65–82.

Bromley, J., Hare, D. J., Davison, K., & Emerson, E. (2004). Mothers supporting children with autistic spectrum disorders: Social support, mental health status and satisfaction with services. Autism, 8(4), 409–423.

Brown, K., & Ryan, R. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822.

Cai, R. Y., Uljarević, M., & Leekam, S. R. (2020). Predicting mental health and psychological wellbeing in mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder: Roles of intolerance of uncertainty and coping. Autism Research, 13(10), 1797–1801.

Carver, C. S. (1997). You want to measure coping but your protocol’too long: Consider the brief cope. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 4(1), 92–100.

Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Weintraub, J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(2), 267.

Chandler, S., Charman, T., Baird, G., Simonoff, E., Loucas, T., Meldrum, D., Scott, M., & Pickles, A. (2007). Validation of the social communication questionnaire in a population cohort of children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 46(10), 1324–1332.

Cheung, R. Y., Leung, S. S., & Mak, W. W. (2019). Role of mindful parenting, affiliate stigma, and parents’ well-being in the behavioral adjustment of children with autism spectrum disorder: Testing parenting stress as a mediator. Mindfulness, 10(11), 2352–2362.

Commonwealth of Australia. (2023). Working together to deliver the NDIS - Independent Review into the National Disability Insurance Scheme: Final Report. Australia

Dabrowska, A., & Pisula, E. (2010). Parenting stress and coping styles in mothers and fathers of pre-school children with autism and down syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 54(3), 266–280.

den Houting, J., Botha, M., Cage, E., Jones, D. R., & Kim, S. Y. (2021). Shifting stigma about autistic young people. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 5(12), 839–841. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(21)00309-6

Ekas, N. V., Lickenbrock, D. M., & Whitman, T. L. (2010). Optimism, social support, and well-being in mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40, 1274–1284.

Esler, A., Bal, V., Guthrie, W., Wetherby, A., Weismer, S., & Lord, C. (2015). The autism diagnostic observation schedule, toddler module: Standardized severity scores. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(9), 2407–2720.

Estes, A., Swain, D. M., & MacDuffie, K. E. (2019). The effects of early autism intervention on parents and family adaptive functioning. Pediatric Medicine (hong Kong, China), 2, 21.

Estes, A., Vismara, L., Mercado, C., Fitzpatrick, A., Elder, L., Greenson, J., Lord, C., Munson, J., Winter, J., & Young, G. (2014). The impact of parent-delivered intervention on parents of very young children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(2), 353–365.

Ferguson, C. J. (2016). An effect size primer: A guide for clinicians and researchers. American Psychological Association.

Green, C. C., Bent, C. A., Smith, J., Chetcuti, L., Uljarević, M., Pye, K., Toscano, G., & Hudry, K. (2024). An evaluation of child and parent outcomes following community based early intervention with randomised parent-mediated intervention for autistic pre-schoolers. Child and Youth Care Forum. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-024-09792-x

Green, C. C., Smith, J., Bent, C. A., Chetcuti, L., Sulek, R., Uljarević, M., & Hudry, K. (2021). Differential predictors of well-being versus mental health among parents of pre-schoolers with autism. Autism, 25(4), 1125–1136.

Green, S. A., & Carter, A. S. (2014). Predictors and course of daily living skills development in toddlers with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44, 256–263.

Gunty, A. L. (2021). Rethinking resilience in families of children with autism spectrum disorders. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice, 10(2), 87–102. https://doi.org/10.1037/cfp0000155

Hastings, R. P., Daley, D., Burns, C., & Beck, A. (2006). Maternal distress and expressed emotion: Cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships with behavior problems of children with intellectual disabilities. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 111(1), 48–61.

Hedley, D., Hayward, S. M., Denney, K., Uljarević, M., Bury, S., Sahin, E., Brown, C. M., Clapperton, A., Dissanayake, C., & Robinson, J. (2021). The association between COVID-19, personal wellbeing, depression, and suicide risk factors in Australian autistic adults. Autism Research, 14(12), 2663–2676.

Henry, J., & Crawford, J. (2005). The short-form version of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44, 227–239. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466505X29657

Hickey, E. J., Stransky, M., Kuhn, J., Rosenberg, J. E., Cabral, H. J., Weitzman, C., Broder-Fingert, S., & Feinberg, E. (2021). Parent stress and coping trajectories in Hispanic and non-Hispanic families of children at risk of autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 25(6), 1694–1708.

Hollestein, L., Lo, S., Leonardi-Bee, J., Rosset, S., Shomron, N., Couturier, D. L., & Gran, S. (2021). MULTIPLE ways to correct for MULTIPLE comparisons in MULTIPLE types of studies. British Journal of Dermatology, 185, 1081–1083.

Ingersoll, B., & Hambrick, D. Z. (2011). The relationship between the broader autism phenotype, child severity, and stress and depression in parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5(1), 337–344.

Jacobson, N. S., & Truax, P. (1992). Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. American Psychological Association.

Janvier, D., Choi, Y. B., Klein, C., Lord, C., & Kim, S. H. (2022). Brief report: Examining test-retest reliability of the autism diagnostic observation schedule (ADOS-2) calibrated severity scores (CSS). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-021-04952-7

Kinderman, P., Tai, S., Pontin, E., Schwannauer, M., Jarman, I., & Lisboa, P. (2015). Causal and mediating factors for anxiety, depression and well-being. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 206(6), 456–460.

Konstantareas, M. M., Homatidis, S., & Plowright, C. (1992). Assessing resources and stress in parents of severely dysfunctional children through the clarke modification of Holroyd’s questionnaire on resources and stress. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 22(2), 217–234.

Leadbitter, K., Aldred, C., McConachie, H., Le Couteur, A., Kapadia, D., Charman, T., Macdonald, W., Salomone, E., Emsley, R., & Green, J. (2018). The autism family experience questionnaire (AFEQ): An ecologically-valid, parent-nominated measure of family experience, quality of life and prioritised outcomes for early intervention. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(4), 1052–1062.

Lord C., Rutter M., DiLavore P., Risi S., Gotham K., Bishop, S. (2012). Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, 2nd Edition (ADOS-2). Western Psychological Services.

Lovibond, S., Lovibond, P. (1995). Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (2 ed.). Psychological Foundation.

Mathew, N. E., Burton, K. L., Schierbeek, A., Črnčec, R., Walter, A., & Eapen, V. (2019). Parenting preschoolers with autism: Socioeconomic influences on wellbeing and sense of competence. World Journal of Psychiatry, 9(2), 30.

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

Mullen, E. M. (1995). Mullen Scales of Early Learning. AGS Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service.

Oono, I. P., Honey, E. J., & McConachie, H. (2013). Parent-mediated early intervention for young children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Evidence-Based Child Health: A Cochrane Review Journal, 8(6), 2380–2479.

Palmer, M., San José Cáceres, A., Tarver, J., Howlin, P., Slonims, V., Pellicano, E., & Charman, T. (2020). Feasibility study of the national autistic society earlybird parent support programme. Autism, 24(1), 147–159.

Patalay, P., & Fitzsimons, E. (2016). Correlates of mental illness and wellbeing in children: Are they the same? Results from the UK Millennium Cohort Study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 55(9), 771–783.

Potter, C. A. (2016). ‘I accept my son for who he is–he has incredible character and personality’: Fathers’ positive experiences of parenting children with autism. Disability & Society, 31(7), 948–965.

Pruitt, M. M., Rhoden, M., & Ekas, N. V. (2018). Relationship between the broad autism phenotype, social relationships and mental health for mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 22(2), 171–180.

Rayan, A., & Ahmad, M. (2018). The psychometric properties of the mindful attention awareness scale among Arab parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 32(3), 444–448.

Rogers, S. J., & Dawson, G. (2010). Early Start Denver Model for Young Children with Autism: Promoting language, learning, and engagement. Guilford Press.

Rogers, S. J., Estes, A., Lord, C., Vismara, L., Winter, J., Fitzpatrick, A., Guo, M., & Dawson, G. (2012). Effects of a brief early start denver model (ESDM)–based parent intervention on toddlers at risk for autism spectrum disorders: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 51(10), 1052–1065.

Rutter M., Bailey A., Lord C., Berument S., Pickles, A. (2003). Social Communication Questionnaire. Western Psychological Services.

Salomone, E., Leadbitter, K., Aldred, C., Barrett, B., Byford, S., Charman, T., Howlin, P., Green, J., Le Couteur, A., & McConachie, H. (2018). The association between child and family characteristics and the mental health and wellbeing of caregivers of children with autism in mid-childhood. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(4), 1189–1198.

Schnabel, A., Youssef, G. J., Hallford, D. J., Hartley, E. J., McGillivray, J. A., Stewart, M., Forbes, D., & Austin, D. W. (2020). Psychopathology in parents of children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence. Autism, 24(1), 26–40.

Smith, J., Aulich, A., Bent, C. A., Constantine, C., Franks, K., Goonetilleke, N., Green, C. C., Lee, P., Ma, E., & Said, H. (2023). “What is early intervention? I had no idea”: Chinese parents’ experiences of early supports for their autistic children in Australia. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 108, 102227.

Smith, J., Sulek, R., Green, C. C., Bent, C. A., Chetcuti, L., Bridie, L., Benson, P. R., Barnes, J., & Hudry, K. (2021). Relative predictive utility of the original and autism-specific Five-Minute Speech Samples for child behaviour problems in autistic preschoolers: A preliminary study. Autism, 26, 1188.

Smith, J., Sulek, R., Van Der Wert, K., Cincotta-Lee, O., Green, C. C., Bent, C. A., Chetcuti, L., & Hudry, K. (2022). Parental imitations and expansions of child language predict later language outcomes of autistic preschoolers. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 53, 1–14.

Sparrow S., Cicchetti D., Balla D. (2005). The Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, 2nd Edition (VABS-II). NCS Pearson Inc.

Stewart-Brown, S. L., Platt, S., Tennant, A., Maheswaran, H., Parkinson, J., Weich, S., Tennant, R., Taggart, F., & Clarke, A. (2011). The warwick-edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): A valid and reliable tool for measuring mental well-being in diverse populations and projects. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 65(Suppl 2), A38–A39.

Swineford, L. B., Guthrie, W., & Thurm, A. (2015). Convergent and divergent validity of the mullen scales of early learning in young children with and without autism spectrum disorder. Psychological Assessment, 27(4), 1364.

Taggart F., Stewart-Brown S., Parkinson J. (2016). Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): User Guide—Version 2. NHS.

Taraban, L., & Shaw, D. S. (2018). Parenting in context: Revisiting belsky’s classic process of parenting model in early childhood. Developmental Review, 48, 55–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2018.03.006

Taylor, L. J., Luk, S. Y. L., Leadbitter, K., Moore, H. L., & Charman, T. (2021). Are child autism symptoms, developmental level and adaptive function associated with caregiver feelings of wellbeing and efficacy in the parenting role? Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 83, 101738. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2021.101738

Tennant, R., Hiller, L., Fishwich, R., Platt, S., Joseph, S., Weich, S., Parkinson, J., Secker, J., & Stewart-Brown, S. (2007a). The Warwick-edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): Development and UK validation. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 5(1), 63.

Tennant, R., Hiller, L., Fishwick, R., Platt, S., Joseph, S., Weich, S., Parkinson, J., Secker, J., & Stewart-Brown, S. (2007b). The Warwick-edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): Development and UK validation. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 5(1), 63.

Trembath, D., Varcin, K., Waddington, H., Sulek, R., Bent, C., Ashburner, J., Eapen, V., Goodall, E., Hudry, K., & Roberts, J. (2023). Non-pharmacological interventions for autistic children: An umbrella review. Autism, 27(2), 275–295.

Vivanti, G., Dissanayake, C., Duncan, E., Feary, J., Capes, K., Upson, S., Bent, C. A., Rogers, S. J., & Hudry, K. (2019). Outcomes of children receiving group-early start denver model in an inclusive versus autism-specific setting: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Autism, 23(5), 1165–1175.

Vivanti, G., Duncan, E., Dawson, G., & Rogers, S. J. (2017). Implementing the group-based Early Start Denver Model for preschoolers with autism. Springer.

Warnick, E. M., Bracken, M. B., & Kasl, S. (2008). Screening efficiency of the child behavior checklist and strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A systematic review. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 13(3), 140–147.

Zablotsky, B., Bradshaw, C. P., & Stuart, E. A. (2013). The association between mental health, stress, and coping supports in mothers of children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43, 1380–1393.

Zhou, B., Xu, Q., Li, H., Zhang, Y., Wang, Y., Rogers, S. J., & Xu, X. (2018). Effects of parent-implemented early start denver model intervention on chinese toddlers with autism spectrum disorder: A non-randomized controlled trial. Autism Research, 11(4), 654–666.

Acknowledgements

We thank the children and their parents for their participation in this study and staff at the Victorian Autism Specific Early Learning and Care Centre for supporting family engagement. We also acknowledge Alexandra Aulich for supporting family engagement and research activities, and the following colleagues who supported data collection activities: Zoe Lazaridis, Daniel Berends, Katherine Natoli, Lillian Bridie, Marissa Leisos, Madeleine Russell-Maynard. Funding was provided by the Australian Government Department of Social Services (DSS), the La Trobe University (LTU) Building Healthy Communities Research Focus Area (RFA) Grant Ready Scheme, La Trobe University School of Psychology and Public Health Income Growth Grant. MU was funded by a Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DECRA) from the Australian Research Council. The funders have had no role in the study design, manuscript drafting or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. Department of Social Services,Australian Government,La Trobe University,Australian Research Council

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.H. and M.U. contributed to the study conception and design. Data were collected by C.C.G., J.S., C.A.B., L.C., and K.H. P.R.B. trained C.C.G. and J.S. in coding the AFMSS. C.C.G. performed analyses and prepared the original draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to interpretation of results and reviewing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Green, C.C., Smith, J., Bent, C.A. et al. Predictors of Change in Wellbeing and Mental Health of Parents of Autistic Pre-Schoolers. J Autism Dev Disord (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-024-06471-7

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-024-06471-7