Abstract

We performed high-resolution numerical simulations of a turbulent flow driven by an oscillating uniform pressure gradient. The purpose was to investigate the influence of a reduced water depth h on the structure and dynamics of the turbulent boundary layer and the transition towards a fully turbulent flow. The study is motivated by applications of oscillatory flows, such as tides, in which h is of the same order of magnitude as the thickness of the turbulent boundary layer \(\delta\). It was found that, if \(h\sim \delta\), the turbulent flow is characterized by (1) an increase of the magnitude of the surface velocity, (2) an increase in the magnitude of the wall shear stress and (3) a phase lead of the velocity profiles, all with respect to the reference case for which \(h\gg \delta\). These results are in agreement with analytical solutions for a laminar oscillatory flow. Nevertheless, if the value of the Reynolds number is too small and \(h\sim \delta\), the flow relaminarizes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Oscillatory flows are of interest in the offshore industry and in coastal engineering as approximations of some of the typical flows occurring in seas, such as the currents generated by waves or by tides. Oscillatory flows have been investigated intensively in the past both experimentally [1,2,3] and numerically [4,5,6,7,8]. The majority of these studies have been performed in experimental set-ups or computational domains where the water depth h was much larger than the thickness of the turbulent boundary layer \(\delta\). Although this is a good approximation for wave boundary layers, it is, however, questionable for tides in several regions.

It is possible to estimate the thickness of the boundary layer \(\delta\) that would exist in an infinitely deep water column, i.e. if \(h\gg \delta\). According to [1, 5], \(\delta\) is defined as the height at which the velocity is maximum for the phase \(\omega t=\pi /2\), where \(\omega\) is the angular frequency and t the time. This phase is defined relatively to the the free-stream velocity \(U_{\infty }=U_{0}\sin (\omega t)\), with \(U_{0}\) the amplitude of \(U_{\infty }\). This definition is valid for both experiments [1] and numerical simulations [5]. Jensen et al. [1] determined the values of \(\delta\) as a function of the Reynolds number using experimental data. They plotted the non-dimensional boundary layer thickness \(\delta \omega /U_{0}\) as a function of the Reynolds number based on the free-stream velocity, \(Re_{fs}\) (see their Fig. 24).

An example of a tidal flow in which \(\delta >h\) can be found along the Dutch coast, around the mouth of the river Rhine. In this region, the tidal flow takes the form of a Kelvin wave [9], and the boundary layer extends over the entire water depth [10]. Under unstratified conditions, the tidal currents are therefore rectilinear along the coast [11, 12], making them a prototype of an environmental oscillatory flow. In this case, \(Re_{fs}\) can be estimated using measurements of the surface velocity (see Table 1) and according to the expression \(Re_{fs}=U_{0}^{2}/(\omega \nu )\), where \(\nu\) is the kinematic viscosity. The values of Table 1 combined with an extrapolation of the scaling graph by Jensen et al. [1] give a non-dimensional boundary layer thickness \(\delta \omega /U_{0} \sim 5\times 10^{-3}\). As a result, \(0.51 \lesssim h/\delta \lesssim 0.80\), i.e. the theoretical boundary layer is larger than the water depth.

However, this scaling law is based on experiments and simulations in which the water depth was much larger than the thickness of the turbulent boundary layer, and this is not the case in the example of the Rhine estuary above. Previously, the influence of a reduced water depth on an oscillatory flow has only been briefly investigated by Li et al. [7]. He showed in a preliminary study that a reduced water depth greatly influences the momentum balance between the pressure gradient, the local acceleration of the flow, and the wall shear stress.

To obtain more insight into the effect of shallowness on oscillatory flows, we propose to study a simplified model in which the effect of the water depth has been isolated. In particular, we focus on flows within the intermittent turbulent regime reaching the start of the fully turbulent regime. This choice has lead to a simplified approach in which variations in the surface elevation and the bottom roughness have been neglected. These choices are further motivated in the discussion section. We performed a series of idealized simulations in which the tidal forcing is modelled by a horizontal uniform oscillating pressure gradient:

with P the pressure, \(\rho\) the density, x the streamwise direction and \(U_{0}\) the previously mentioned amplitude of the free-stream velocity. This approach has been used in [4, 5, 7], and the simplicity of such a numerical set-up allows easy comparisons with experiments in similar configurations [1, 2]. We have simulated the oscillatory flow for three different values of the Reynolds number

based on the thickness of the Stokes boundary layer \(\delta _{s}=\sqrt{2\nu /\omega }\). Note that this definition differs from that of \(\delta\) which was previously defined as the depth of the velocity maximum at \(\omega t=\pi /2\). In fact, this depth in the laminar case is given by \(\delta =\tfrac{3}{4} \pi \delta _{s}\) [2]. The chosen values for \(Re_{\delta }\) (\(\text {Re}_{\delta }=990\), 1790 and 3460) correspond to tests 6, 8 and 10 in the study of Jensen et al. [1]. For each value of \(\text {Re}_{\delta }\), we varied the ratio \(h/\delta _{s}\) from 5 to 70.

In the remaining part of this manuscript, we first briefly present a laminar analytical solution. Afterwards, we describe the numerical model and the set-up. Finally, we expose our numerical results on the turbulent flow in shallow water environments through a study of mean velocity profiles, the mean wall shear stress, and the depth-integrated turbulent kinetic energy (TKE).

2 Laminar solution

In the laminar case, the flow is governed by the simplified Navier–Stokes equations,

in which the streamwise velocity u depends on the vertical coordinate y (positive upwards) and on time.

This equation can be rewritten as

where \(\tau\) represents the shear stress defined as \(\tau =\rho \nu (\partial u/\partial y)\). In order to analyse the influence of the reduced water depth on the velocity profile, the analytical solutions to Eq. (3) can be studied via: (1) a phase difference \(\varPhi\), and (2) a change in the amplitude A. Both \(\varPhi\) and A are defined with respect to the free-stream velocity \(U_{\infty }\), i.e. the time-signal of the velocity infinitely far away from the bottom wall. For more details about the analytical solutions, the reader is referred to the Appendix. Since the flow is investigated in terms of velocity profiles, water depth and wall shear stress, three different phase shifts and three different amplitudes are considered: \(\varPhi _{\infty }\), \(\varPhi _{h, \text {f}}\) and \(\varPhi _{\tau }\), and \(A_{\infty }\), \(A_{h, \text {f}}\) and \(A_{\tau }\). The shift \(\varPhi _{\infty }\) and the amplitude \(A_{\infty }\) are not related to a reduced water depth. They simply denote the phase shift and amplitude of the infinite velocity profile as a function of the position y in the water column; the shift \(\varPhi _{h, \text {f}}\) and amplitude \(A_{h, \text {f}}\) denote the phase shift and the amplitude of the surface velocity signal in a reduced water depth configuration as a function of the total water depth h; shift \(\varPhi _{\tau }\) and amplitude \(A_{\tau }\) denote the phase shift and the amplitude of the wall-shear stress signal in a reduced water depth configuration as a function of the total water depth h.

Phase shift (a) and the amplitude (b) of the surface velocities and the wall shear stress with respect to \(U_{\infty }\). Note that \(\varPhi _{\infty }\) and \(A_{\infty }\) are function of \(y/\delta\) while \(\varPhi _{h,\text {f}}\), \(\varPhi _{\tau }\), \(A_{h,\text {f}}\) and \(A_{\tau }\) are function of \(h/\delta\)

As expected, the phases and amplitudes change with changing depth. Figure 1 shows these different phase shifts (i.e. positive phase differences \(\varPhi\)) defined with respect to \(U_{\infty }\) as a function of \(y/\delta\) (for \(\varPhi _{\infty }\)) or \(h/\delta\) (for \(\varPhi _{h, \text {f}}\) and \(\varPhi _{\tau }\)). This figure also shows of \(A_{\infty }\), \(A_{h, \text {f}}\) and \(A_{\tau }\) From Fig. 1, it can be seen that the influence of the water depth on the velocity phase and amplitude becomes significant from \(h \lesssim 2\delta\). For a general description, three different cases can be identified.

Case 1: \(h\gtrsim 2 \delta\). The wall shear stress leads the free-stream velocity by an angle \(\varPhi _{\tau }=\pi /4\). The momentum balance is mainly between the local acceleration and the pressure gradient. When h decreases, the phase shifts and amplitudes remain constant but the contribution of the wall shear stress to the momentum balance becomes increasingly more important.

Case 2:\(\delta \lesssim h \lesssim 2\delta\). When \(h \sim 2\delta\), the velocity profile changes to accommodate to the no-stress boundary condition at the free-surface which results in slight adjustments of \(\varPhi _{h, \text {f}}\), \(\varPhi _{\tau }\) and \(A_{h, \text {f}}\). When h approaches \(\delta\), the amplitude of the free surface velocity \(A_{h,\text {f}}\) reaches a maximum and the phases \(\varPhi _{h, \text {f}}\), \(\varPhi _{\tau }\) increase significantly. This is due to the size reduction of the upper water layer lying in between the heights \(y=\delta\) and \(y=h\). As this upper layer is resisting, via viscous forces, the motion of the lower water layer, lying between \(y\lesssim \delta\), its size reduction implies a reduction of its damping effect on the lower such that \(A_{h, \text {f}}\) can reach a maximum.

Case 3:\(h \lesssim \delta\). First, the increasing amplitude of the velocity generates higher gradients close to the wall resulting in an increase in the shear stress amplitude \(A_{\tau }\). Second, when h becomes too small, the oscillating boundary cannot fully develop anymore: \(A_{h, \text {f}}\) and \(A_{\tau }\) both decrease towards zero. At the same time, \(\varPhi _{h, \text {f}}\) and \(\varPhi _{\tau }\) keep increasing until they converge to \(\pi /2\).

The analytical laminar solutions give an overview of the influence of the water depth on the oscillating boundary layer in the laminar regime. It is also a model for turbulent flows if the eddy viscosity is considered constant. Nevertheless, a constant eddy viscosity is not realistic (see the plane averaged eddy viscosity calculations of Salon et al. [5, 15, 16]). In order to investigate the turbulent oscillatory flow accurately, we performed numerical simulations which we describe in the following sections.

3 Numerical set-up

In high resolution numerical simulations, the value of the Reynolds number that can be achieved is limited by computational requirements. In fact, the value for most tidal flows cannot be reached with the current day resources. This is also the case for the Rhine estuary: the characteristics of the Rhine estuary presented in the introduction (i.e. \(\omega =1.41\times 10^{-4}\hbox {s}^{-1}\); \(\nu =1.14 \times 10^{-6}\hbox {m}^{2}\) s\(^{-1}\) and \(0.7\hbox {m s}^{-1}\le U_{0} \le 1.1\hbox { m s}^{-1}\)) suggest \(Re_{\delta }\sim 10^{5}\). The highest Reynolds number that we can compute with the present day resources at a satisfactory resolution is \(Re_{\delta }=3460\), and this is also the highest value of \(Re_{\delta }\) for which experimental data is available. A similar ’down-scaling’ approach has already been used by Salon et al. [15] to study turbulence in an oscillatory flow subjected to rotation. Simulations with \(Re_{\delta }=1790\) (using large eddy simulations, abbreviated ’LES’) and \(Re_{\delta }=990\) (using direct numerical simulations, abbreviated ’DNS’), have also been performed to investigate the influence of this parameter on the flow, between the laminar and fully turbulent flow. For these values of the Reynolds number, either fully developed turbulence (for \(Re_{\delta }=1790\)) or intermittent turbulence (for \(Re_{\delta }=990\)) is present [5, 6], although not throughout the full tidal cycle. For each value of the Reynolds number, simulations have been carried out for five different values of \(h/\delta _{s}\) i.e., 5, 10, 25, 40 and 70. In total, 15 combinations of values for \(h/\delta _{s}\) and \(Re_{\delta }\) have been carried out.

In the simulations, the filtered, three-dimensional continuity and Navier–Stokes equations are solved in non-dimensional form:

where \({\bar{\cdot }}\) denotes a filtered quantity and * denotes a non-dimensional quantity. The \(z^{*}\)-direction is the spanwise direction and \(w^{*}\) its associated velocity, \(v^{*}\) is the vertical velocity and \(\delta _{i1}\) the Kronecker delta. The first term on the right hand side represents the filtered pressure gradient, the second term represents the viscous forces, the third term the large scale oscillating driving force and the fourth term the modelled subgrid-scale stresses. The non-dimensional coordinates \(x_{i}^{*}=(x^{*},y^{*},z^{*})\) have been made non-dimensional with h, the velocity variables \(u_{i}^{*}=(u^{*},v^{*},w^{*})\) with \(U_{0}\), the time \(t^{*}\) with \(h/U_{0}\), the pressure \({\bar{p}}^{*}\) with \(\rho U_{0}^{2}\) and the subgrid scale stresses \(\tau _{ij}^{*}\) with \(U_{0}^{2}\). The numerical algorithm has been previously used successfully in similar studies [5, 15, 16] and is based on the fractional step method for non-staggered grids of Zang et al. [17]. A successive over relaxation (SOR) with multi-grid is used to solve the Poisson equation and the algorithm is overall second order accurate in both time and space. For more details see [5]. The code was already parallelized in the spanwise direction using the Message Passing Interface (MPI) technique. Recently, the pressure solver (i.e. the bottleneck in terms of computational requirements) has also been parallelized in a second direction. This has made the algorithm roughly one order of magnitude faster according to our own tests.

The subgrid scales are parametrized using the dynamic Smagorinsky approach of Armenio and Piomelli [18]. The simulations at \(Re_{\delta }=1790\) and \(Re_{\delta }=3460\) are performed with LES, while the simulations at \(Re_{\delta }=990\) are performed in DNS (i.e. with finer resolution and \(\tau _{ij}^{*}=0\)). This is motivated by the fact that, although the dynamic Smagorinsky model has been proved to give excellent results for highly unsteady flows [19], it is not able to reproduce well the relaminarization occurring at the lower Reynolds number of \(Re_{\delta }=990\) [5].

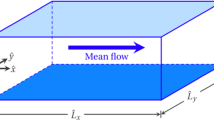

Sketch of the computational domain, with the oscillating pressure gradient in the x direction. The estimation of the metric size of the domain in the streamwise and the spanwise direction is based on the value of \(\delta _{s}\) for \(\omega =1.41 \times 10^{-4}\hbox { s}^{-1}\) and \(\nu =1.14\times 10^{-6}\hbox { m s}^{-1}\)

In most of the simulations, the computational domain was chosen with horizontal sizes of \(65\delta _{s}\) in the streamwise direction and \(32\delta _{s}\) in the spanwise direction (see Fig. 2). Only for \(Re_{\delta }=1790\) or \(Re_{\delta }=990\) and \(h/\delta _{s}=5\) (i.e. simulations characterized by high intermittency), the domain was doubled in the horizontal directions, keeping the grid-spacing constant. The boundary conditions are periodic in the horizontal directions, a no-slip condition is applied at the bottom and a rigid-lid no-stress condition at the top. This means that dynamic vertical variations in the water level were neglected. For the simulations with \(Re_{\delta }=1790\) or \(Re_{\delta }=990\) and \(h/\delta _{s}=5\) wall imperfections in the spirit of Blondeaux and Vittori [20] are applied to favour retransition to turbulence after previous relaminarization. The horizontal resolution in wall units, defined by \(x_{i}^{+}=x_{i}\nu /u_{\tau }\) (with \(u_{\tau }=\sqrt{\tau _{w}/\rho }\) the friction velocity and \(\tau _{w}\) the wall shear stress), was chosen such that \(\varDelta x^{+}\) (streamwise) was less than 45\(y^{+}\) for the LES simulations and 12\(y^{+}\) for the DNS simulations. The spanwise grid spacing \(\varDelta z^{+}\) was chosen to be at most \(22y^{+}\) for the LES simulations and \(14y^{+}\) for the DNS simulations. In the vertical, wall-normal direction, the cells were clustered close to the wall. The ratio between the vertical lengths of two successive cells (i.e. stretching) was kept lower than 3%. This limit was set such, since a higher stretching would reduce the accuracy of the numerical algorithm. As a result, the cell size in the vertical direction increases from \(\varDelta y^{+}=2y^{+}\) to \(\varDelta y^{+}=22y^{+}\) (to \(\varDelta y^{+}=14y^{+}\) for the DNS simulations). Once the maximum grid spacing was reached, the grid spacing was kept constant in the remaining part of the domain. These criteria have been based on the estimated size of turbulence structures [21, 22] and results from previous studies [5, 6]. For simulations characterized by a low \(h/\delta _{s}\) ratio, time-step convergence has been checked by decreasing the Courant number. It was found that the Courant number value of 0.6 gave converged results for all the simulations except for \(Re_{\delta }=1790\), \(h/\delta _{s}=5\) (i.e. simulations characterized by high intermittency) for which convergence was achieved for a Courant number equal to 0.3. Additionally, it has to be mentioned that the results for the simulations with \(Re_{\delta }=990\) and \(h/\delta _{s}=5\) where still highly grid dependent, probably because the flow relaminarize through the whole cycle.

Initial turbulence was generated by interpolating the velocity field from a converged turbulence simulation (either a plane channel flow or an oscillatory flow at lower resolution) for which the mean velocity was removed. The spin-up of the simulations takes several periods. Therefore, we discard the first five periods and started to average from period six to skip the transient regime. The velocity profiles and other statistical quantities have been obtained by averaging over horizontal planes as well as by performing phase averaging. By taking advantage of the anti-symmetry of the flow between \(\omega t\) and \(\omega t+\pi\), statistics were accumulated over about 40 time windows (i.e. 20 periods).

4 Results

4.1 Validation against experimental data

Comparison between the results of the numerical simulations and the data from the experimental results of Jensen et al. [1]. On the left hand side (a) the numerically computed, plane and phase averaged wall shear stress is displayed for the three values of the Reynolds numbers in the largest depth configuration (i.e. \(h/\delta _{s}=70\)). On the right hand side (b), the plane and phase-averaged velocity profiles for \(Re_{\delta }=3460\) and \(h/\delta _{s}=70\) are shown for \(\omega t=\left\{ \pi /4, \pi /2, 3\pi /4, \pi \right\}\). Wall shear stress data for \(Re_{\delta }=990\) was not available

The data of Jensen et al. [1] has been used to validate several numerical simulation studies with similar set-ups to ours, including Costamagna et al. [6] (for \(Re_{\delta }=990\)), Salon et al. [5] (for \(Re_{\delta }=990\) and \(Re_{\delta }=1790\)) and Radakrishnan and Piomelli [4] (for \(Re_{\delta }=3460\)). Jensen et al. [1] performed their experiments in a U-shaped water tunnel with a 10 m long working section, a 0.39 m width and a 0.28 m depth. The velocities were measured with two laser-Doppler anemometers, and the wall shear stress with a hot film probe using a sample interval of 14 and 48 ms within an oscillating cycle of 9.72 s (i.e. 200–600 samples per cycle). For more details about the experimental set-up, the reader is referred to Jensen et al. [1].

Among the several numerical studies, the one of Salon et al. [5] used a previous version of our code. Salon and co-authors extensively compared their numerical results at \(Re_{\delta }=1790\) and \(h/\delta _{s}=40\) to the experimental results in terms of wall shear stress, velocity profiles, turbulence intensities and Reynolds shear stresses, and they claimed a very good agreement except for some discrepancies between some of the numerical and experimental turbulent intensities. Since our simulations at \(Re_{\delta }=3460\) are the first simulations at this high Reynolds number value for which the wall layer is resolved (in Radakrishnan and Piomelli [4] a wall model was used), we display the wall shear stress and four velocity profiles in Fig. 3 together with the available data of Jensen et al. [1]. Note that \(\left\langle \cdot \right\rangle\) denotes a plane and phase-averaged quantity. The wall shear stress agreement is excellent for \(Re_{\delta }=1790\) and very good for for \(Re_{\delta }=3460\) except that the maximum in the numerical signal is slightly higher than the maximum in the experimental signal. This feature was also observed by Radhakrishnan & Piomelli [4] and the difference is consistent with the rounding performed by Jensen et al. [1] (private communication) to compute the value of the Reynolds number.

The agreement of the velocity profiles is also excellent in the wall region but differs non-negligibly higher in the water column. However, we can argue about the accuracy of the experimental data higher in the water-column. Indeed, far from the wall, the surface velocity evolves as \(\sin (\omega t)\) and the velocity profiles at \(\omega t=\pi /4\) and \(\omega t=3\pi /4\) should coincide. This concurrence is observed in the numerical profiles but not in the experimental data. Furthermore, the divergence between numerical and experimental results are also visible in the modelled wall simulations of Radhakrishnan and Piomelli. A possible explanation of these discrepancies is that the experimental set-up does not lead to a perfectly symmetric flow as suggested by the authors themselves in [23] and later pointed out by Salon et al. [5].

4.2 Velocity profiles and turbulent boundary layer thickness

The velocity profiles for the three values of \(Re_{\delta }\) (i.e. 990, 1790 and 3460) and \(h/\delta _{s}=70\) are displayed in Fig. 4, and the turbulent boundary layer thickness \(\delta\) can be estimated from the graph by determining, for each value of \(Re_{\delta }\), the height at which the velocity profile for the phase \(\omega t=\pi /2\) is maximum.

Table 2 shows that the turbulent boundary layer grows in size with \(Re_{\delta }\). As a result every simulation is characterized by a specific value of \(h/\delta\) and the simulations cover a wide range of values for \(h/\delta\), including simulations that are not influenced and simulations strongly influenced by the finite water depth. Three simulations have a value for \(h/\delta\) similar to those of the Rhine estuary.

4.3 Surface velocity and turbulent wall shear stress

Plane and phase averaged velocity profiles at \(\omega t=\pi /2\) (left column, i.e. a, c, e) and wall shear stress series (right column, i.e. b, d, f) for \(Re_{\delta }=990\) (top, i.e a, b), \(Re_{\delta }=1790\) (middle, i.e. c and d) and \(Re_{\delta }=3460\) (bottom, i.e. e and f). The laminar analytical solutions are also displayed and the subscript 5 refers to \(h/\delta _{s}=5\)

The impact of a reduced water depth on the flow properties is observable in Fig. 5. In this figure, the wall shear stress is shown as a function of time, and the velocity at \(\omega t=\pi /2\) is shown as a function of the depth, for all the combinations of values of \(Re_{\delta }\) and \(h/\delta _{s}\). For simulations with \(Re_{\delta }=990\) and \(Re_{\delta }=1790\), and \(h/\delta _{s}\ge 25\), the velocity profiles are hardly affected by the water depth, but for simulations with \(Re_{\delta }=3460\), the profile is already affected when \(h/\delta _{s}=25\). According to Table 2, \(h/\delta =1.98\) for the simulation with \((Re_{\delta }=1790;h/\delta _{s}=25)\) and \(h/\delta =1.42\) for the simulation with \((Re_{\delta }=3460; h/\delta _{s}=25)\). This means that the effect of the water depth becomes clearly visible for \(1.5 \lesssim h/\delta \lesssim 2.0\).

Similar to the velocity profiles, the wall shear stress is also affected by the water depth. For all the values of the Reynolds number simulated, the signals of the wall shear stress as a function of time are nearly equal as long as \(h/\delta \ge 25\) but the signals react differently for each \(Re_{\delta }\)-value if a smaller depth is considered, see Fig. 5. For \(Re_{\delta }=1790\) and for \(Re_{\delta }=3460\), the amplitude of the wall shear stress is the largest for \(h/\delta _{s}=10\), followed by \(h/\delta _{s}=5\) and finally by \(h/\delta _{s}\ge 25\). This behaviour suggests that for \(0.50 \lesssim h/\delta \lesssim 2.00\), the amplitude of the wall shear stress is maximum. In contrast, for \(Re_{\delta }=990\) the magnitude of the wall shear stress decreases slightly for \(h/\delta _{s}=10\) compared to the cases with \(h/\delta _{s}\ge 25\) and almost collapses on that of the laminar solution for \(h/\delta _{s}=5\). This drop is probably related to a complete relaminarization of the flow except for the deceleration phase where disturbances are still generated. Despite this complete relaminarization is not observed for the other simulations, some elements suggest that a strong decrease of turbulent activity occurs for these other simulations too, although during only part of the oscillation cycle. In fact, it is well known that the transition to turbulence is marked by a sudden increase in the slope of the wall shear stress time-series [1, 5, 6]. This phenomenon of sudden increase is observed in all the simulations but the wall shear stress follows the laminar solution for some part of the cycle only (1) for \(Re_{\delta }=990\) and \(h/\delta _{s}\ge 10\), (2) for \(Re_{\delta }=1790\) and \(h/\delta _{s}\le 10\) and (3) for \(Re_{\delta }=3460\) and \(h/\delta _{s}=5\). This behaviour suggests that these latter simulations experience partial relaminarization, the simulation with \(h/\delta _{s}=5\) and \(Re_{\delta }=990\) experiences complete relaminarization while the other simulations just experience a reduction in turbulent activity.

Additionally, a more careful look at the velocity profiles for \(Re_{\delta }=990\), \(Re_{\delta }=1790\) and \(h/\delta _{s}=5\), indicated already relaminarization since the velocity profiles converge towards the analytical laminar solution. This tendency might be caused by the water depth becoming too small to contain the largest turbulence scales. Earlier studies of oscillating pipe flows have also shown that reducing the diameter of the pipe delays the transition to turbulence [24, 25]. During this regime, the boundary layer thickness probably switches between its laminar and turbulent thickness. This process is further investigated by means of the TKE in the next section.

4.4 Turbulent kinetic energy

In order to estimate the amount of turbulence in the computational domain, we define the resolved plane averaged TKE, \(\left\langle E\right\rangle _{p}\), by

where \(\left\langle \cdot \right\rangle _{p}\) refers to plane averaging only. The choice of not using a combined plane and phase averaged velocity for the computation of the plane and phase averaged TKE, E, is motivated by the turbulence intermittency observed in some simulations. For example, for \(h/\delta _{s}=5\) and \(Re_{\delta }=1790\), there is a certain randomness in the phase at which transition to turbulence occurs, and the flow at a specific phase can be either laminar during a certain cycle or turbulent during a different cycle. The mean velocity of the flow in laminar conditions is different from the mean velocity of the flow in turbulent conditions. As a result, computing \({\left\langle E\right\rangle _{p}}\) for each phase using the local mean velocity gives more reliable results than using the phase-averaged mean velocity. The mean resolved TKE E is defined as the phase average of the \({\left\langle E \right\rangle _{p}}\) over the number of cycles \(n_{c}\):

where the cycle numbers 1 and \(n_{c}\) do not account for the discarded cycles in the transient regimes. To have a fair comparison between the different simulations, E is integrated between 0 and \(5\delta _{s}\):

This quantity is displayed as a function of time in Fig. 6. For \(Re_{\delta }=3460\), the minimum value of \(E_{5\delta _{s}}\) decreases with \(h/\delta _{s}\). Furthermore, the lowest values of \(E_{5\delta _{s}}\) for \(h/\delta _{s}=5\), \(Re_{\delta }=3460\) occur slightly before \(\omega t=\pi\), just before the increase in slope of the wall shear stress, a strong indication of relaminarization in the acceleration phase. This feature confirms that the sudden increase in slope of the wall shear stress signal is due to transition to turbulence after previous relaminarization. For the lower \(Re_{\delta }\) values, the results are similar. The temporal minimum of \(E_{5\delta _{s}}\) still decreases with \(h/\delta _{s}\), and the extent of the cycle for which \(E_{5\delta _{s}}\) stays low increases, particularly for \(h/\delta _{s}=5\). Additionally, for all the values of \(Re_{\delta }\), \(E_{5\delta _{s}}\) decreases during large parts of the cycle for \(h/\delta _{s}=10\) when compared to the simulations with higher \(h/\delta _{s}\) ratios. The turbulent kinetic energy shows a maximum, which is actually the highest for \(h/\delta _{s}=10\). This could mean that there are higher levels of turbulence during the decelerating phases of the cycle even if the rest of the cycle relaminarizes. This finding was already suggested by the wall shear stress in Fig. 5: the evolution of the wall shear stress has a higher maximum but also suggests a longer period of turbulence activity reduction for \(h/\delta _{s}=10\) and \(Re_{\delta }=1790\) or \(Re_{\delta }=3460\) than for the large depth simulations.

An additional feature is the apparent decrease of \(E_{5\delta _{s}}\) with increasing \(Re_{\delta }\) values. This could have several origins: (1) at high Reynolds numbers, turbulent kinetic energy is faster transported away from the wall and does not remain in the region \(0\le y \le 5\delta _{5}\); (2) the use of DNS for \(Re_{\delta }=990\) while LES is used for \(Re_{\delta }=1790\) and \(Re_{\delta }=3460\) resulting in a larger fraction of the resolved fluctuations (this only explains the increase in \(E_{5\delta _{s}}\) between \(Re_{\delta }=990\) and \(Re_{\delta }=1790\)). The exact cause of this increase in \(E_{5\delta _{s}}\) remains however unclear and is of minor importance for our investigation.

4.5 Amplitude and phases of the velocities and wall shear stresses

Figures 5 and 6 have shown that both the value of \(Re_{\delta }\) and the value of \(h/\delta _{s}\) impact the velocity, the wall-shear stress and TKE. Since the flow is periodic in time, the velocity and the wall shear-stress can be investigated by means of the phase and the amplitude of the periodic signal, in a similar way as for the laminar solution.

Phase shift (a) and the amplitude (b) of the surface velocity with respect to the free-stream velocity, for \(Re_{\delta }=990, Re_{\delta }=1790\) or \(Re_{\delta }=3460\). Note that \(\varPhi _{\infty }\) and \(A_{\infty }\) are functions of \(y/\delta\) while \(\varPhi _{h,\text {f}}\) and \(A_{h,\text {f}}\) are functions of \(h/\delta\). For turbulent flows enough data points are available to present \(\varPhi _{\infty }\) and \(A_{\infty }\) as lines but one point per simulation is available for \(\varPhi _{h,\text {f}}\) and \(A_{h, \text {f}}\) and they are presented as symbols. The subscript ’an’ refers to the laminar analytical solution while the subscript ’num’ refers to the numerical solution

The results for \(\varPhi _{\infty }\), \(\varPhi _{h,\text {f}}\), \(A_{\infty }\) and \(A_{h, \text {f}}\) are shown in Fig. 7 for the turbulent results as well as for the analytical solution. The dependence of \(A_{h,\text {f}}\) on \(h/\delta\) and of \(A_{\infty }\) on \(y/\delta\) are similar for the data from turbulent numerical simulations and the laminar analytical solutions. The amplitudes \(A_{\infty }\) and \(A_{h,{\text {f}}}\) are maximum around \(h=\delta\) and then decrease towards zero. The deviation of \(A_{\infty }\) curves near the bottom is due to the differences in vertical shear between a laminar bottom boundary and a turbulent bottom boundary. The agreement between the laminar and turbulent results for \(\varPhi _{h, \text {f}}\) and \(\varPhi _{\infty }\) is more qualitative: for the simulations as well as for the laminar theory, \(\varPhi _{h, \text {f}}\) increases with decreasing \(y/\delta\) and \(\varPhi _{\infty }\) increases with decreasing \(h/\delta\). However, the rate of increase is faster and the limit values are different when the flow is laminar than when the flow is turbulent: \(\varPhi _{\infty }\) increases towards \(\pi /4\) in the laminar case while it increases towards approximately \(\pi /16\) in the turbulent case. Additionally, the data points from the simulations characterized by relaminarization of the flow are slightly out of trend. A last remarkable feature is that both the turbulent profiles of \(A_{\infty }\) and of \(\varPhi _{\infty }\) collapse on each other, for the three Reynolds numbers. This proves that \(\delta\) is an excellent scaling parameter.

The variation of the magnitude \(A_{\tau }\) and phase-shift \(\varPhi _{\tau }\) of the wall shear stress is also studied, but the analysis of this quantity is more delicate. Indeed Fig. 5 has shown that the temporal signal of the wall-shear stress is not sinusoidal for the turbulence simulations which makes the identification of the phase shift rather difficult. As a result, the phase lead of the wall shear stress with respect to the free-stream velocity is defined as the phase difference between the maximum wall shear stress and the maximum free stream velocity, in agreement with Jensen et al. [1]. Nevertheless, also this definition is difficult to handle. Previous studies have shown that turbulence was characterized by a reduction of the phase lead of the wall shear stress with respect to the free-stream velocity [1, 2], while the laminar theory suggests an increase of this phase lead with decreasing \(h/\delta _{s}\) and thus with \(h/\delta\), see Fig. 1). We are, therefore, in the presence of two competing mechanisms: on one side, transition to turbulence decreases the phase lead of the wall shear stress while the interference between the boundary layer and the surface increases this phase lead. Nevertheless, the amplitude and phase angles for the wall shear stress have been displayed in Fig. 8. In order to eliminate the influence of the Reynolds number, \(A_{\tau }\) and \(\varPhi _\tau\) have been scaled, so that for high values of \(h/\delta\), \(A_{\tau }\) and \(\varPhi _{\tau }\) are close to their laminar value, respectively \(\pi /4\) and \(\sqrt{2}/2\). The amplitude of the wall shear stress \(A_{\tau }\) for the turbulence simulations shows a similar behaviour as in the laminar theory, as long as the flow stays turbulent. The data points lying slightly out of trend correspond to the lowest Reynolds number (\(Re_{\delta }=990\)). For this value of \(Re_{\delta }\), there is no maximum in the wall shear stress and \(A_{\tau }\) decreases with \(h/\delta\) due to relaminarization.

The behaviour of the turbulent phase shift \(\varPhi _{\tau }\) is very different from the laminar case: it decreases instead of increasing for decreasing \(h/\delta\). It remains unclear if this discrepancy is due to the relaminarization occurring for low values of \(h/\delta\), to the non-sinusoidal shape of the wall shear stress signal or to a combination of these two phenomena. The reason of this behaviour could partly be clarified with simulations at a much higher Reynolds number, but they are not achievable with the current resources yet.

5 Discussion

Numerical simulations have shown that a reduction of the water depth strongly affects turbulent oscillatory flows by generating changes in the amplitude and in the phase of both the velocity signals and the wall shear stress signals. The evolution of the phases and the amplitudes with the water depth shows a similar trend to the analytical solution in which a constant (kinematic) viscosity has been used. In many environmental applications, turbulence is not resolved but modelled for cost efficiency purposes. In this regard, an analytical model of the turbulent flow using a constant eddy viscosity approach could give a quick first estimation of the velocity profiles and the wall-shear stress. However, for more accurate results, environmental flows often rely on somewhat more sophisticated turbulence models, such as the \(k-\varepsilon\) model. The \(k-\varepsilon\) model could be a time saving alternative to high resolution simulations, under the condition that it is able to reproduce the features observed in the present numerical simulations and in particular the relaminarization. In this regard, the results presented in this paper could be an interesting bench mark for \(k-\varepsilon\) based solvers (such as in the paper by Pu [26]), so that more realistic oscillatory flows, incorporating free-surface, bottom roughness, rotation or just a higher value for the Reynolds number, can be simulated reliably at lower computational costs.

The role played by the ratio \(h/\delta\) in the theoretical solution of the oscillating boundary layer flow is also relevant for applications in environmental flows. Our results confirm the finding of Li et al. [7], that for small ratios of \(h/\delta\) (such as tidal flows along the Dutch coast), the momentum balance is between the local acceleration, the driving pressure gradient and the wall shear stress \(\tau _{w}\), whereas for large values of \(h/\delta\) (tidal currents in deep oceans, wave boundary layers or seiches in lakes), the balance is mainly between the local acceleration and the driving pressure gradient. The claim by Lorke et al. [27], that the momentum balance for seiches in an Alpine lake (lake Alpnach) is not comparable with the momentum balance of tidal oscillatory flows, is explained by the large \(h/\delta\) ratio of the lake when compared to tidal flows. Note that the oscillatory flow in this Lake is generated by a diurnal wind forcing. As a result, free surface effects do not play an important role and due to the absence of Coriolis force (because of the small size of the lake), Lake Alpnach can be considered as a prototype example of our deep-water simulations.

Additionally, the present results could play a role in estimating the free-stream velocity or the friction parameter \(f_{w}\) of oscillating tidal flows such as for example in the North-Sea, the main channel of Skagit Bay (studied for example in [28]) or the tidal channel in Three Mile Slough (studied for example in [29]). The results even suggest that the tidal free-stream velocity along the Dutch coast, presented in the introduction, could be overestimated by 10–20% since it does not coincide, as implicitly assumed, with the surface velocity. However, it is necessary to evaluate how accurate the oscillating boundary layer model is for actual tidal flows. As mentioned in the introduction, four simplifying assumptions have been used: (1) the absence of the Coriolis force, (2) the presence of a flat bottom, (3) a rigid-lid assumption and a (4) a relatively low Reynolds number. The first assumption, the absence of the Coriolis force can be justified because the purely oscillating motion of the flow is a direct result from the Earth’s rotation, via the Kelvin wave. The incorporation of the Coriolis force would generate a Stokes–Ekman boundary layer [15, 16] and generate tidal ellipses that are only observed near the Rhine mouth under stratified conditions, or far away from the coast [11]. For the current study, it seems less relevant. The second assumption, ignoring of bottom roughness, is clearly a disadvantage of the model. However, roughness is known to facilitate transition to turbulence [1], so that it can be expected that oscillatory flows with rough bottoms are less affected by relaminarization, maintaining the similar trends for laminar and turbulent oscillating flow at lower value of the Reynolds number. The third assumption, the rigid lid assumption is probably the most challenging one. Near the Rhine mouth, the tidal amplitude varies roughly between 1m during neap tide to 2 m during spring tide on a water depth of approximately 20 m [30], so that the free surface might play an important role. These first three assumptions could be investigated in the future with a DNS or LES approach providing tailor-made models. However, the fourth assumption, i.e. increasing the Reynolds number value significantly, is not realistic in the near future. Therefore, although we do believe that the reduction of the water depth has a non-negligible impact on oscillating tidal flows, we recommend to quantify this impact with Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes simulations. The present results are then very useful as a reference case and including understanding of the basic phenomena a calibration for the Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes simulations.

6 Conclusion

The influence of a reduced water depth on turbulent oscillatory flows has been investigated using a high resolution numerical approach (direct numerical simulations and wall-resolving large eddy simulations) and compared to a laminar analytical solution. In this study the water depth h was compared to the thickness of the boundary layer \(\delta\). It was found that turbulent, oscillatory flows are characterized by an increase of the phase lead of the surface velocity and the wall shear stress on the free-stream velocity, if the water depth is decreased. The evolution of the phase and the amplitude of the turbulent velocity time-signals shows similar trends to the analytical laminar solution. However, if the water depth is decreased too much, the flow relaminarizes. We would expect that for very high Reynolds numbers this relaminarization will only take place for very low values of \(h/\delta _{s}\) (i.e. \(h/\delta _{s}<5\)), but we cannot currently confirm or validate this statement due to the high computational costs such simulations require.

The results of our study may have implications for applications of oscillatory flows such as tidal flows. For example, the tidal currents along the Dutch coast are in the shallow water regime. However, the influence of other physical actors such as free-surface or bottom-roughness have been neglected in the present study and they might be responsible for additional effects on these tidal flows. Therefore, we believe that the present findings constitute an excellent benchmark for typical environmental fluid mechanics configurations and their associated numerical solvers with which the impact of a reduced water depth on environmental flows can be further investigated. From a more fundamental point of view, we intend to extend this study to investigate the ability that oscillatory flows have to mix river-induced stratification. The water depth is believed to play a major role here. In too deep water, the turbulent bottom boundary layer does not extend over the entire water depth and will be unable to mix the surface layer. In too shallow water layers, the mixing potential will be altered by relaminarization.

References

Jensen BL, Sumer BM, Fredsøe J (1989) Turbulent oscillatory boundary layers at high Reynolds numbers. J Fluid Mech 206:265

Carstensen S, Sumer BM, Fredsøe J (2010) Coherent structures in wave boundary layers. Oscillatory motion. Part 1. J Fluid Mech 646:169

Chen D, Chen C, Tang FE, Stansby P, Li M (2007) Boundary layer structure of oscillatory open-channel shallow flows over smooth and rough beds. Exp Fluids 42(5):719

Radhakrishnan S, Piomelli U (2008) Large-eddy simulation of oscillating boundary layers: model comparison and validation. J Geophys Res 113(C2)

Salon S, Armenio V, Crise A (2007) A numerical investigation of the Stokes boundary layer in the turbulent regime. J Fluid Mech 570:253

Costamagna P, Vittori G, Blondeaux P (2003) Coherent structures in oscillatory boundary layers. J Fluid Mech 474:1

Li M, Sanford L, Chao SY (2005) Effects of time dependence in unstratified tidal boundary layers: results from large eddy simulations. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 62(1):193

Spalart PR, Baldwin BS (1989) Direct simulation of a turbulent oscillating boundary layer. Turbul Shear Flows 6:417–440

Van Alphen J, De Ruijter W, Borst J (1988) Physical processes in estuaries. Springer, Berlin, pp 70–92

de Boer GJ (2009) On the interaction between tides and stratification in the Rhine region of freshwater influence. Ph.D. thesis, Delft Univeristy of Technology, The Netherlands

Visser AW, Souza AJ, Hessner K, Simpson JH (1994) The effect of stratification on tidal current profiles in a region of freshwater influence. Oceanol. Acta 17(4):369

Simpson JH, Bos WG, Schirmer F, Souza AJ, Rippeth TP, Jones SE, Hydes D (1993) Periodic stratification in the Rhine ROFI in the north sea. Oceanol. Acta 16(1):23

Zimmerman J (1986) The tidal whirlpool: a review of horizontal dispersion by tidal and residual currents. Neth J Sea Res 20(2–3):133

Van der Giessen A, De Ruijter W, Borst J (1990) Three-dimensional current structure in the Dutch coastal zone. Neth J Sea Res 25(1–2):45

Salon S, Armenio V, Crise A (2009) A numerical (LES) investigation of a shallow-water, mid-latitude, tidally-driven boundary layer. Environ Fluid Mech 9(5):525

Salon S, Armenio V (2011) A numerical investigation of the turbulent Stokes–Ekman bottom boundary layer. J Fluid Mech 684:316

Zang Y, Street RL, Koseff JR (1994) A non-staggered grid, fractional step method for time-dependent incompressible Navier–Stokes equations in curvilinear coordinates. J Comput Phys 114(1):18

Armenio V, Piomelli U (2000) A lagrangian mixed subgrid-scale model in generalized coordinates. Flow Turbul Combust 65(1):51

Scotti A, Piomelli U (2001) Numerical simulation of pulsating turbulent channel flow. Phys Fluids 13(5):1367

Blondeaux P, Vittori G (1994) Wall imperfections as a triggering mechanism for Stokes-layer transition. J Fluid Mech 264:107

Piomelli U, Balaras E (2002) Wall-layer models for large-eddy simulations. Ann Rev Fluid Mech 34(1):349

Pope SB (2001) Turbulent flows. IOP Publishing, Bristol

Sumer B, Laursen T, Fredsøe J (1993) Wave boundary layers in a convergent tunnel. Coast Eng 20(3–4):317

Hino M, Sawamoto M, Takasu S (1976) Experiments on transition to turbulence in an oscillatory pipe flow. J Fluid Mech 75:193

Tuzi R, Blondeaux P (2008) Intermittent turbulence in a pulsating pipe flow. J Fluid Mech 599:51

Pu JH (2015) Turbulence modelling of shallow water flows using Kolmogorov approach. Comput Fluids 115:66

Lorke A, Umlauf L, Jonas T, Wüest A (2002) Dynamics of turbulence in low-speed oscillating bottom-boundary layers of stratified basins. Environ Fluid Mech 2(4):291

Gross TF, Nowell AR (1983) Mean flow and turbulence scaling in a tidal boundary layer. Cont Shelf Res 2(2–3):109

Stacey MT, Monismith SG, Burau JR (1999) Measurements of Reynolds stress profiles in unstratified tidal flow. J Geophys Res Oceans 104(C5):10933

Rijkswaterstaat waterinfo. https://waterinfo.rws.nl/#!/kaart/waterhoogte-t-o-v-nap/. Accessed: 2018 Nov 28

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by STW now NWO/TTW (the Netherlands) through the project “Sustainable engineering of the Rhine region of freshwater influence” (#12682). We would like to thank Prof. B. Mutlu Sumer for providing the experimental data used to validate the simulations. Finally, we would like to thank project PRACE, and particularly Dr. John Donners, for improving the parallelization of the computer software, making the algorithm one order of magnitude faster.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

A: Analytical solutions

A: Analytical solutions

Depending on the top boundary condition used, two different analytical solutions are possible for Eq. (3). If an infinite depth is assumed,

where the subscript \(\infty\) refers to the infinite-depth case. In the case of a finite-depth, a no-stress boundary condition is applied at \(y=h\). In this case, the solution is given by

and the subscript \(\text {f}\) refers to the finite-depth solution. The real constants \(A_{11}\), \(A_{12}\), \(A_{21}\) and \(A_{22}\) are given by

The two velocities \(u_{\infty }\) and \(u_{\text {f}}\), and the wall-shear stress associated to the latter, \(\tau _{w, \text {f}}\), can be put under the form

where the amplitudes \(A_{\infty }\), \(A_{h,\text {f}}\) and \(A_{\tau }\) read

and the phases \(\varPhi _{\infty }\), \(\varPhi _{h,\text {f}}\) and \(\varPhi _{\tau }\) read

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kaptein, S.J., Duran-Matute, M., Roman, F. et al. Effect of the water depth on oscillatory flows over a flat plate: from the intermittent towards the fully turbulent regime. Environ Fluid Mech 19, 1167–1184 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10652-019-09671-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10652-019-09671-3