Abstract

Introduction

Symptomatic anastomotic stricture is a rare but major complication after left-sided colorectal surgery. Hydraulic balloon dilatation is the first-line treatment in cases where the complication occurs, but 20% of patients present with refractory strictures after multiple sessions. Endoscopic stricturoplasty with the use of a linear stapler is a novel therapeutic alternative for those difficult cases.

Materials and Methods

We identified all patients in our department who underwent endoscopic stricturoplasty with a linear stapler between 2004 and 2022. The technical, periinterventional, and follow-up data of the patients were retrospectively analyzed.

Results

We identified nine patients who fulfilled our inclusion criteria. The procedure was technically possible in eight cases, whereas in one case, the anatomy of the anastomosis did not allow for a correct placement of the stapler. All patients with a technically successful procedure were relieved from their symptoms and could have their ostomy reversed. There was no periprocedural morbidity and mortality. Two patients presented with a recurrent stricture eight and 26 months after the initial stricturoplasty, and the procedure was successfully repeated in both cases.

Conclusions

Endoscopic stricturoplasty is a feasible, safe, and minimally invasive alternative for the treatment of refractory anastomotic strictures in the distal colon and rectum for patients with a suitable anatomy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The developments in surgical techniques and available devices over the last decades have decreased the overall morbidity and mortality of colorectal surgery and expanded its indications. Nevertheless, anastomotic strictures are still a major complication after colorectal resections. Up to 30% of patients experience benign anastomotic strictures, most of which occur within the first year after surgery, with the vast majority being localized in the lower sigmoid colon and rectum [1,2,3,4]. The absolute diameter of the anastomosis does not seem to have a linear association with the presence of symptoms, such as constipation, tenesmus, ribbon stools, or even bowel obstruction, and thus, most authors reserve the indication for treatment only for symptomatic strictures, which are estimated between 50 and 75% of all strictures [2, 5, 6]. In cases of anastomoses located distally to an ostomy, where symptoms would only occur after reversal of the ostomy, a minimum diameter for a functional anastomosis has to be defined preoperatively, and an easy passage with the standard 9mm endoscope is the most common criterion.

In the past, the surgical revision of the anastomosis was the only treatment option available, even if it was technically demanding and associated with high morbidity [4, 7]. Nowadays, endoscopic methods allow for a minimally invasive yet effective treatment, and surgery is reserved only for the rare failure cases. Among the various endoscopic methods suggested, balloon dilatation is the most commonly used first-line treatment: it is quick, safe, and easy to perform even in an outpatient setting; it offers an adequate treatment for most patients; and it is currently the gold standard for the treatment of benign strictures in the colorectum [1, 8]. However, multiple sessions are usually necessary to relieve symptoms, and up to 20% of the strictures can be refractory to this treatment option [9]. Different methods including incision with electrocautery and transanal surgery have been proposed for the treatment of such recurring strictures; however, the evidence of the published data is very low, and no general suggestion can be made regarding these rare and difficult cases [8].

We have previously described a technique for endoscopic stricturoplasty with the endoluminal use of a linear stapler for the treatment of refractory anastomotic strictures in the distal colon and rectum [10]. The aim of our current study is to present the first series of patients treated with this technique, focusing on its technical aspects and long-term results.

Patients and Methods

We identified all patients treated with an endoscopic stricturoplasty with a linear stapler for anastomotic strictures in the distal colon and rectum in the Central Interdisciplinary Endoscopy Department of the University Hospital of Mannheim between 2004 and 2022. The anonymized patient data were extracted from our endoscopic database and retrospectively analyzed. An approval of the local ethics committee was acquired.

Indication

The main indication for endoscopic treatment was the presence of obstruction symptoms including obstipation, tenesmus, and bowel obstruction in combination with endoscopic verification of an anastomotic stricture in the lower sigmoid colon or rectum. For patients with an ostomy, the indication was seen for anastomoses that could not be passed with the standard 9 mm endoscope. The first-line treatment was hydraulic balloon dilatation up to a maximum diameter of 20 mm. In cases of very low strictures, where a stable position of the endoscope was not possible, Heger dilatators were used instead. A refractory anastomotic stricture was defined as a failure to treat the patient’s symptoms after multiple endoscopic attempts. If primary surgery was performed because of cancer, a biopsy was routinely performed to exclude tumor recurrence. From these refractory cases, patients with a suitable anatomy were selected for endoscopic stricturoplasty with the use of a linear stapler. The ideal anatomy for this procedure is that of an end-to-side or side-to-side descendorectostomy, commonly seen after sigmoidectomy or low anterior rectal resection. In order for the stapler branches to be positioned correctly, the anastomotic stricture had to be short (< 1 cm in length) and diaphragm-like. Additionally, an at least 3-cm-long blind loop of the rectum had to be present on the distal side of the anastomosis, orientated parallel to the proximal colon, allowing correct placement of the stapler.

A special group selected for this procedure consisted of patients with a coloanal anastomosis and a J-pouch in which a bridge of scarry tissue was formed between the opposite stapler lines of the pouch, directly above the anastomosis, thus occluding the pouch outlet. All patients were thoroughly informed about the therapeutic alternatives and signed an informed consent before the procedure.

Endoscopic Technique

All procedures were performed under propofol sedation in the endoscopy suite. All procedures were performed according to the initial description of the technique by an experienced endoscopist with additional experience in transanal surgery (G.K. or K.K.) [10].

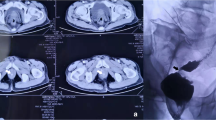

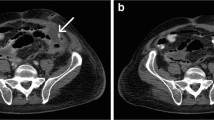

The patient was positioned in the left lateral position. A 5 mm pediatric endoscope was introduced, and the stricture was carefully explored. If the stricture was too narrow to allow the passage of the slim branch of the linear stapler, a hydraulic balloon dilatation up to 10 mm was performed. Subsequently, a single use linear cutter stapler with a 70-mm-long handle and a magazine angulation capability of up to 45° was introduced transanally. The stapler magazines used had six rows of staples—three on each side of the blade—and were suitable for use on the colon (intermediate tissue thickness). The length of the magazine—30 mm, 40 mm, or 55 mm—was selected according to the individual characteristics of each patient. Under direct endoscopic view, the stapler head was angulated appropriately, the slim branch was passed through the stricture into the proximal colon, and the wide branch was positioned in the blind loop of the rectum, distal to the anastomosis. The stapler was advanced as far as possible so that the maximum amount of tissue could be captured between its branches and was subsequently closed and fired, dividing the diaphragm (Fig. 1). If necessary, the procedure was repeated with a further magazine until the diaphragm was completely divided and the anastomosis was wide open.

Endoscopic stricturoplasty with linear stapler for a persistent anastomotic stricture. a and b Anastomotic stricture after laparoscopic sigmoidectomy with side-to-side anastomosis (initial diameter 2 mm). c Stricture after initial balloon dilatation and insertion of the ARAMIS operation rectoscope. The blind end of the rectum offers enough space for the branches of the linear stapler (arrow). d Introduction of the linear stapler. e and f Insertion of one branch of the stapler through the anastomosis and of the other branch in the blind loop of the rectum. g and h Result at the end of the procedure. i Final result in the 6 months follow-up (diameter 14 mm)

In the cases of the scarry tissue bridge inside the J-pouch, the branches of the stapler were positioned on either side of the bridge, and the procedure was repeated until the whole bridge was divided and the pouch was completely open again.

Postprocedural Care and Follow-Up

All procedures were performed in an inpatient setting. The patients could be discharged after the second day if they did not show any signs of bleeding or discomfort. The first endoscopic follow-up was scheduled 4–6 weeks after the initial procedure (Fig. 2). Further follow-up was based on the symptoms of each patient and the oncological standards in the case of cancer patients.

Results

We identified 11 procedures on nine patients—five male and four female—fulfilling the inclusion criteria of our analysis within the study period. The surgical history, including indication and type of surgery, of the patients is summarized in Table 1.

Five patients developed moderate but persistent symptoms including abdominal pain, obstipation, and tenesmus, whereas one patient presented with recurring symptoms of acute bowel obstruction. Three patients had a loop ileostomy, and the indication for the procedure was based on the endoscopic findings. All patients underwent several sessions of endoscopic balloon dilatation or bouginage with Heger dilatators prior to the endoscopic stricturoplasty, which could neither alleviate the symptoms nor improve the endoscopic findings. The median interval from the initial anastomosis to the endoscopic stricturoplasty was 10 months (range 4–26 months).

The median distance of the anastomosis of the anal verge was 9 cm (range 2–15 cm), and the median diameter was 5.5 mm (range 1–10 mm). The procedure was technically successful in eight out of nine patients, resulting in a technical success rate of 89%. Six patients received the typical endoscopic stricturoplasty with linear stapler as described above, and in two patients, a bridge of scarry tissue that formed in the J-pouch was divided. In one case, and despite previous endoscopic assessment, the anatomy of the anastomosis did not allow for an adequate positioning of the linear stapler, and the procedure was discontinued.

The median number of stapler magazines used per procedure was two (range 1–3), and their lengths varied from 30 to 55 mm. A technical difficulty that occurred during the first procedures was the air leakage through the anal canal between the endoscope and the stapler. From the seventh procedure onward, a 3.5 cm operation rectoscope (ARAMIS, Sapi Med S.p.A., Alessandria, Italy) was additionally used. The rectoscope sealed the anal canal, thus offering a stable pneumorectum, and the endoscope and stapler were introduced through its working channels. Apart from that, there were no further technical problems during insertion, orientation, placement, and firing of the stapler. The median duration of the procedure was 60 min (range 41–68 min), and the median hospital stay was 2 days (range 1–4 days). No complications occurred, periinterventional morbidity and mortality were nil. The clinical outcomes of the patients are summarized in Table 2.

All symptomatic patients reported a significant relief of their symptoms after the procedure, and in the three patients with an ostomy, a reversal was performed shortly after the stricturoplasty without any postoperative signs of obstruction, thus resulting in a clinical success rate of 100% after a technically successful procedure (Fig. 2).

The median follow-up was 25 months (range 12–206 months). Follow-up endoscopy revealed a recurrent stricture in two patients, eight and 26 months after the initial procedure, respectively; the stricture was treated with a second session of endoscopic stricturoplasty. Further follow-up did not reveal any recurrence, and no further procedures were necessary.

Discussion

Anastomotic stricture remains a challenging complication of colorectal surgery, significantly impairing quality of life and often prolonging the necessity of an ostomy [5]. Simple endoscopic procedures, such as balloon dilatation and bouginage, can adequately treat most of these strictures and spare the patients major surgical revisions, yet in some cases, the patients’ symptoms cannot be resolved even after multiple procedures [9, 11]. In this case series, we present an alternative endoscopic procedure for the treatment of refractory anastomotic strictures, making use of a linear stapler under direct view with a flexible endoscope. Our findings support the feasibility of this technique in an appropriately selected group of patients with favorable anatomy. All patients in our study could be relieved from their symptoms after one or rarely two sessions of endoscopic stricturoplasty without any morbidity or mortality, and the long-term results revealed no further recurrences.

The exact pathophysiology of anastomotic strictures is yet to be defined. Several studies have identified a series of risk factors for the development of symptomatic strictures after colorectal surgery, including anastomotic leak, perioperative radiation, obesity, older age, ischemia, stapled anastomosis, and diverticular disease or diverticulitis as indications for the initial resection [1, 5, 12, 13]. However, none of the risk factors can identify which patients will respond well to standard endoscopic treatment, a fact that is also evident in our study. Among our patients, only one had received preoperative radiation, and one further had experienced an anastomotic leak requiring endoscopic negative pressure therapy. Five of our nine patients had undergone multiple surgical procedures (Table 1), suggesting that the extensive scarring in and around the rectal wall might also affect the development of a refractory stricture. Diverticular disease or diverticulitis was indeed the most common indication for the primary resection in our case series, but this might also be attributed to selection bias because of the geometry of the anastomosis. The anastomosis after sigmoidectomy is typically located higher and the lumen of the distal colon is wider than after rectal resection with a low anastomosis, thus facilitating better placement of the stapler and making those patients better candidates for the procedure.

Endoscopic balloon dilatation is currently the most common first-line treatment method for anastomotic strictures since it is easy to perform even in an outpatient setting and has an acceptable safety profile with a perforation rate from 3 to 5% and negligible bleeding rates [1, 8, 9, 14,15,16,17]. The main point of criticism remains the necessity for multiple dilatations, with only 25–50% of the strictures being resolved after the first session and some patients requiring up to nine consequent procedures, thus increasing the overall risk of adverse events and impairing the patients’ quality of life [16, 18,19,20]. The same principles and outcomes also apply for bouginage with Savary-Gillard or Heger dilatators [21,22,23]. Even after multiple sessions, 18–20% of the strictures will not be resolved, and further treatment will be necessary [9, 24]. We believe that this selected group of patients can profit from more complex and invasive therapeutic options; therefore, in our study, we reserved the indication for the endoscopic stricturoplasty with a linear stapler only for patients who did respond to multiple sessions of balloon dilatation or bouginage.

We believe that the main factor for failure of balloon dilatation and bouginage is the uncontrolled tearing of the anastomosis in multiple sites, causing an equally uncontrolled healing with rebuilding of scarry tissue along the entire anastomosis. Supporting this theory is the fact that different methods, such as electrocautery incision, inflicting a controlled and localized trauma to the scarry tissue of the stricture seem to have similar initial success rates of up to 80% but with significantly lower recurrence rates and higher long-term patency [25,26,27,28]. This principle applies also to the stricturoplasty with the use of a linear stapler since the tissue trauma is localized in the area of the incision, without any radial forces excreted to the rest of the anastomosis. The lack of use of electrocautery further reduces the collateral tissue damage, thus potentially reducing the formation of scarry tissue. A further advantage of our technique in comparison to electrocautery incision is the additional sealing of the tissue around the incision through the staple line. This allows for a further advancement of the stapler and an extension of the incision to the normal rectal wall, if necessary, thus making the procedure more effective, with a minimal risk of perforation compared to electrocautery incision [29].

The use of staplers in the treatment of anastomotic strictures is not new, and circular staplers have been used as early as 1986 in an attempt to cut out the scarry tissue and “redo” the anastomosis. However, the main problem remains the placement of the anvil in the proximal side of the anastomosis, which either requires a transabdominal approach with colotomy or an extreme dilatation of the stenosis prior to the procedure in order to transanally introduce the 28 mm or 32 mm anvil [30,31,32]. Linear staplers are easier to introduce through a narrow anastomosis, and if the stricture is short and the geometry favorable, they can safely divide the entire fibrotic tissue diaphragm. To date, there are very few case reports of the use of linear staplers for similar procedures, most of them in a form of transanal surgery with rigid instruments and general anesthesia, and they have shown encouraging results [33,34,35]. The main advantage of our technique is the possibility to perform it under flexible endoscopic guidance in the endoscopy suite and under sedation, without the need for general anesthesia or a long-time slot in the operating room.

Patient selection is crucial for the success of this method. If the indication for the primary resection was cancer, multiple biopsies should be performed before the procedure to not oversee tumor recurrence. The anatomy and geometry of the anastomosis must then be carefully evaluated to assess the possibility of an adequate placement of the stapler. The best candidates for this procedure according to our experience are patients after sigmoidectomy with an end-to-side or side-to-side descendorectostomy. In that case, the blind end of the rectum offers enough space for the placement of the wide branch of the linear stapler, while the other branch is inserted through the anastomosis. Despite thorough previous evaluation, correct positioning of the stapler proved to be impossible in one of our cases, and this possibility should be openly discussed with the patients before the procedure. Given the proper patient selection, endoscopic stricturoplasty with linear stapler can offer very good periprocedural and long-term results for these challenging strictures.

The main limitation of our study is patient selection and the small number of cases. However, the nature of the disease and the technical aspects of the method do not justify its general application for all strictures, especially given the therapeutic alternatives. The evaluation of this technique in a prospective setting and in comparison to other methods would offer more solid data to its efficacy and could possibly objectify the characteristics of the patients that can most profit from it, but the rarity of suitable cases makes such a study at the moment technically impossible.

Conclusions

The findings of our study show that endoscopic stricturoplasty with the use of a linear stapler is an effective, safe, and minimally invasive technique for the treatment of recurring and refractory anastomotic strictures in the distal colon and rectum. Careful patient selection is crucial in order to identify patients with suitable anatomy who will profit from this procedure.

References

Luchtefeld MA, Milsom JW, Senagore A, Surrell JA, Mazier WP. Colorectal anastomotic stenosis. Results of a survey of the ASCRS membership. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32:733–736.

Ambrosetti P, Francis K, De Peyer R, Frossard JL. Colorectal anastomotic stenosis after elective laparoscopic sigmoidectomy for diverticular disease: a prospective evaluation of 68 patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:1345–1349.

Bertocchi E, Barugola G, Benini M, Bocus P, Rossini R, Ceccaroni M et al. Colorectal anastomotic stenosis: lessons learned after 1643 colorectal resections for deep infiltrating endometriosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26:100–104.

Bravi I, Ravizza D, Fiori G, Tamayo D, Trovato C, De Roberto G et al. Endoscopic electrocautery dilation of benign anastomotic colonic strictures: a single-center experience. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:229–232.

Polese L, Vecchiato M, Frigo AC, Sarzo G, Cadrobbi R, Rizzato R et al. Risk factors for colorectal anastomotic stenoses and their impact on quality of life: what are the lessons to learn? Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:e124. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1463-1318.2011.02819.X.

Aston NO, Owen WJ, Irving JD. Endoscopic balloon dilatation of colonic anastomotic strictures. Br J Surg. 1989;76:780–782.

Schlegel RD, Dehni N, Parc R, Caplin S, Tiret E. Results of reoperations in colorectal anastomotic strictures. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:1464–1468.

Clifford RE, Fowler H, Manu N, Vimalachandran D. Management of benign anastomotic strictures following rectal resection: a systematic review. Colorectal Dis. 2021;23:3090–3100.

Suchan KL, Muldner A, Manegold BC. Endoscopic treatment of postoperative colorectal anastomotic strictures. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1110–1113.

Reinshagen K, Müldner A, Reinshagen S, Kähler G. Endoscopically controlled strictureplasty for stenotic colorectal anastomosis. Endoscopy. 2005;37:873–875.

Smith LE. Anastomosis with EEA stapler after anterior colonic resection. Dis Colon Rectum. 1981;24:236–242.

Bressan A, Marini L, Michelotto M, Frigo AC, Da Dalt G, Merigliano S et al. Risk factors including the presence of inflammation at the resection margins for colorectal anastomotic stenosis following surgery for diverticular disease. Colorectal Dis. 2018;20:923–930.

Shimada S, Yagi Y, Yamamoto K, Matsuda M, Baba H. Novel treatment of intractable rectal strictures associated with anastomotic leakage using a stenosis-cutting device. Int Surg. 2007;92:82–88.

Bequis A, Gonzalez M, Fernandez Aramburu J, Huespe P, Duran S, Hyon SH et al. Fluoroscopy and endoscopy-guided transanastomotic rendezvous: a novel technique for recanalization of a completely obstructed colorectal anastomosis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2021;36:627–631.

Park CH, Yoon JY, Park SJ, Cheon JH, Kim TIL, Lee SK et al. Clinical efficacy of endoscopic treatment for benign colorectal stricture: balloon dilatation versus stenting. Gut Liver. 2015;9:73–79.

Virgilio C, Cosentino S, Favara C, Russo V, Russo A. Endoscopic treatment of postoperative colonic strictures using an achalasia dilator: short-term and long-term results. Endoscopy. 1995;27:219–222.

Venkatesh KS, Ramanujam PS, McGee S. Hydrostatic balloon dilatation of benign colonic anastomotic strictures. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35:789–791.

Alonso Araujo SE, Costa AF. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic balloon dilation of benign anastomotic strictures after oncologic anterior rectal resection: report on 24 cases. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2008;18:565–568.

Nguyen-Tang T, Huber O, Gervaz P, Dumonceau JM. Long-term quality of life after endoscopic dilation of strictured colorectal or colocolonic anastomoses. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1660–1666.

De Lange EE, Shaffer HA. Rectal strictures: treatment with fluoroscopically guided balloon dilation. Radiology. 1991;178:475–479.

Duce AM, de Yébenes AB, Garcés G, González-Bueno CM. Instrument for dilatation of stenotic colorectal anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1990;33:160–161.

Werre A, Mulder C, Van Heteren C, Bilgen ES. Dilation of benign strictures following low anterior resection using Savary-Gilliard bougies. Endoscopy. 2000;32:385–388.

Xinopoulos D, Kypreos D, Bassioukas SP, Korkolis D, Mavridis K, Scorilas A et al. Comparative study of balloon and metal olive dilators for endoscopic management of benign anastomotic rectal strictures: clinical and cost-effectiveness outcomes. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:756–763.

Osera S, Ikematsu H, Odagaki T, Oono Y, Yano T, Kobayashi A et al. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic radial incision and cutting for benign severe anastomotic stricture after surgery for lower rectal cancer (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:770–773.

Tan Y, Wang X, Lv L, Zhang J, Guo T, Tang X et al. Comparison of endoscopic incision and endoscopic balloon dilation for the treatment of refractory colorectal anastomotic strictures. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2016;31:1401–1403.

Lin D, Liu W, Chen Z, He X, Zheng Z, Lan P et al. Endoscopic stricturotomy for patients with postoperative benign anastomotic stricture for colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2022;65:590–598.

Hunt TM, Kelly MJ. Endoscopic transanal resection (ETAR) of colorectal strictures in stapled anastomoses. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1994;76:121.

Jakubauskas M, Jotautas V, Poskus E, Mikalauskas S, Valeikaite-Tauginiene G, Strupas K et al. Management of colorectal anastomotic stricture with transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM). Tech Coloproctol. 2018;22:727–729.

Khan F, Shen B. Endoscopic treatment of concurrent colorectal anastomotic stricture and prolapse. Endoscopy. 2018;50:E235–E236.

McKee R, Pricolo VE. Stapled revision of complete colorectal anastomotic obstruction. Am J Surg. 2008;195:526–527.

Rees JRE, Carney L, Gill TS, Dixon AR. Management of recurrent anastomotic stricture and iatrogenic stenosis by circular stapler. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:944–947.

Hinton CP, Celestin LR. A new technique for excision of recurrent anastomotic strictures of the rectum. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1986;68:260.

Chew SSB, King DW. Use of endoscopic titanium stapler in rectal anastomotic stricture. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:283–285.

Anvari M. Endoscopic transanal rectal stricturoplasty—PubMed. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1998;8:193–196.

Pagni S, McLaughlin CM. Simple technique for the treatment of strictured colorectal anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:433–434.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. There is no grant support and no internal or external funding for this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KK performed part of the procedures and the documentation, gathered, and analyzed the data, performed the literature review, and wrote the manuscript. CR contributed in the review of the literature, the preparation, and the revision of the manuscript. GK performed part of the procedures and the documentation, contributed in the review of the literature, the preparation, and the revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kouladouros, K., Reissfelder, C. & Kähler, G. Endoscopic Stricturoplasty with Linear Stapler: An Efficient Alternative for the Refractory Rectal Anastomotic Stricture. Dig Dis Sci 68, 4432–4438 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-023-08156-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-023-08156-0