Abstract

Compassion fatigue (CF), or the extreme stress and burnout from helping others, is widely considered to be harmful to professional well-being. Due to a lack of awareness and education around CF in healthcare professionals, mental health clinicians may feel particularly unsure about how to treat these common symptoms. There is considerable symptom overlap between CF and several other presentations, including posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, insomnias, and substance abuse disorders. Evidenced-based assessments designed to measure symptoms of CF are discussed, as well as screening measures for overlapping presentations. Treating fellow clinicians and pre-professionals comes with unique ethical considerations, most notably privacy concerns that may impact professional development. The culture of training programs does not adequately prepare pre-professionals for psychological well-being. As psychologists, it is our ethical responsibility to advocate for changes in graduate education and at our training sites. By utilizing evidenced-based strategies, such as acceptance and commitment therapy, we can assist professionals and pre-professionals in building resilience as they navigate a career in the helping professions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Clinical Vignette

Jada, who identifies as a Black 28-year-old female, was self-referred to treatment after attending a webinar on compassion fatigue she found while browsing a local trauma conference. Jada is a sixth-year graduate-student clinician enrolled in a PhD program in clinical psychology. In her current full-time internship placement, she is providing services to veterans who are diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Jada mentions that these veterans were typically deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan, often on numerous tours. She provides prolonged exposure therapy to these veterans, which often involves gathering detailed descriptions of traumatic and gruesome events.

Jada reports feeling overwhelmed by the number of clients she is currently seeing at the clinic, especially because she has not finished writing her dissertation. Jada experiences nightmares about war, which frequently disrupt her sleep. She has overslept several times in the last few weeks and was late to a meeting with her supervisor, which has not happened before. Jada describes feeling exhausted, even on days when she oversleeps. Jada states she has been arguing with her boyfriend about the amount of time she is devoting to the relationship. She is currently in a long-distance relationship after moving for internship.

Jada has not yet found professional or personal spaces with other people of color in the community. Jada reports feeling isolated and unfamiliar with her new location. She said that she often avoids speaking with the other interns, as they seem to have it all together. Jada became distraught last week after a meeting with her supervisor, as she is over a week behind in her notes. She describes this behavior as quite unusual, as she is typically on time and organized. Jada is worried her supervisor will not provide a good recommendation for post-doc placements in the future. Lately, she feels overwhelmed by the numerous demands and thinks about giving up. However, she feels there is no choice but to press forward with completing her doctorate, due to her investment of time and resources.

Jada is concerned she will “mess up” with one of her clients or forget to do something important such as scheduling her dissertation. She is worried her supervisor or fellow interns will believe she is not qualified if she reveals her feelings to others. Recently, Jada burst into tears while discussing her client’s treatment in peer supervision. She said that she felt extremely embarrassed and that the other intern seemed surprised by her emotional display. Jada reports trying to leave the intern office as quickly as possible to avoid getting into conversations with the other interns. She reports feeling less enthusiastic about veterans’ issues lately and is questioning her career focus.

To add to these challenges, Jada’s dissertation centers around the measurement of PTSD in veteran populations. She says that she often finds herself distracted while trying to work on her dissertation and reports little progress despite hours of work. Jada says that during the compassion fatigue webinar, she felt as though they were describing her experience. She is currently seeking resources to address her feelings of stress, isolation, and despair.

Compassion Fatigue: Burnout, Secondary Traumatic Stress, and Compassion Satisfaction

Compassion fatigue (CF), or the extreme stress and burnout from helping others, is widely considered to be harmful to a professional’s well-being. Different conceptualizations of CF can be found in the literature and several different terms such as secondary traumatic stress, vicarious stress, compassion stress, and burnout have been used interchangeably with the term CF, which has led to considerable confusion (Figley, 2002; Gentry, 2002; Joinson, 1992).

Carla Joinson, a registered nurse, is credited with being the first to use the term CF in a 1992 article. She described CF as a unique form of burnout where caregivers experience a “loss of the ability to nurture” (Joinson, 1992; p. 119). She described characteristics of CF she observed in nurses, such as detachment, feelings of irritability, anger, depression, a lack of joy in general, dreading going to work, fatigue, and physical complaints (e.g., frequent headaches or stomachaches). Further, she asserted that all these characteristics led to ineffective job performance (Joinson, 1992).

Professor and trauma expert, Charles Figley, was the first to use the term “secondary traumatic stress” (STS) to describe CF. Figley referred to CF as the “cost of caring,” which represents the negative emotional, cognitive, and behavioral consequences that result from working with traumatized clients (Figley, 2002). Figley (1995, 2002) further described CF as “a state of tension and preoccupation with traumatized patients by re-experiencing the traumatic events, avoidance/numbing of reminders and persistent arousal associated with the patient” (Figley, 1995; p.1435). It differs from posttraumatic stress in that the exposure is indirect such as knowing and hearing about it from another (Figley, 1995).

In recent years, CF is described as a multi-component construct that consists of both burnout and secondary traumatic stress (Stamm, 2010), which consolidates many of the terms used in the field. Burnout occurs as a result of an individual experiencing the chronic negative effects of stress and is a state of physical, mental, and emotional exhaustion (Maslach et al., 2001). Burnout is often associated with stressful work and stressful experiences in a work setting (Stamm, 2010). Burnout happens from stress that builds up gradually overtime (i.e., individuals may feel it coming on; Figley, 2002; Gentry, 2002; Stamm, 2010). Signs and symptoms of burnout include diminished enjoyment in work, arguing with coworkers, loss of morale, physical and emotional exhaustion, and depression and anxiety (Gentry, 2002). Another component of CF, secondary traumatic stress (STS), is associated with the secondary exposure to trauma, traumatic events, or the extreme stress experienced by others (usually through the role as a helper or caregiver). It tends to be less gradual or predictable than burnout and tends to come on suddenly without much warning (Figley, 2002; Gentry, 2002; Stamm, 2010). STS is associated with PTSD and its symptoms except the difference is the event is not directly experienced but indirectly experienced through helping another (e.g., hearing about the trauma, seeing posts on social media, stories/images on the news etc.; Figley, 2002; Gentry, 2002; Stamm, 2010). Examples of signs and symptoms of STS include intrusive thoughts/nightmares about the stressful experience or trauma, tension/anxiety, re-experiencing the event, avoiding reminders, going numb or feeling a since of depersonalization, and hypervigilance (Gentry, 2002).

Some risk factors for CF include negative coping skills, high levels of stress, low levels of social support, previous history of experiencing one’s own trauma, and bottling up or avoiding emotions (Gentry, 2002). A primary protective factor for CF is self-care (Ludick & Figley, 2017). While self-care is often discussed in the professional literature, there is no unifying definition for the construct of self-care. Furthermore, many different domains and components of self-care are discussed among researchers (Rupert & Dorociak, 2019), which include a wide variety of activities such as eating healthy, taking a bath, engaging in recreational activities, spiritual practices, and more (Saakvitne et al., 1996). In practical terms, self-care involves behaviors and activities that may prevent physical illness and that promote physical and emotional health and personal well-being through building resilience (Rupert & Dorociak, 2019). According to Ludick and Figley (2017), self-care is a critical component of CF resilience because it can ameliorate the harmful effects of trauma work by lowering levels of STS.

Furthermore, according to Schwanz and Paiva-Salisbury (in press) the beneficial effects of self-care may not be realized by the individual due to their ingrained beliefs about self-care. These self-care beliefs may play a role in prioritizing and even engaging in self-care activities. For example, helpers may recognize the importance of engaging in self-care but may feel guilty when they take time for themselves instead of helping others and therefore neglect their own self-care needs. The limited value placed on self-care and resilience building by our society increases the chances of CF warranting clinical attention.

Clinical, Ethical, and Diversity Considerations

In preparing for a future career, pre-professionals are not frequently ready to self-reflect on the signs and symptoms of CF (Pakenham & Stafford-Brown, 2012). Some graduate training programs in clinical or counseling psychology may not provide formal education about CF. In fact, many do not even promote resilience-building practices such as self-care. However, there are some training sites that provide services to traumatized individuals, which may include training on CF. As clinicians, we should not assume a client has this knowledge even within the field of psychology. Therefore, while Jada self-referred for these negative feelings related to CF, her clinician should still assess her knowledge regarding CF. The lack of awareness of CF often leads to development of more serious psychological symptomatology (Figley, 1995). Consequently, individuals may not present to treatment until symptoms have progressed to cause significant disruption in current functioning such as excessive stress, depressive like symptoms, anxiety, or with substance abuse concerns. The culture of the graduate program and the internship site can contribute both positively and negatively to the acceptable forms of coping and of expressing need for assistance (Barnett & Cooper, 2009). The practice of self-care may not be modeled by those in the graduate program’s leadership roles. Similarly, some aspects of North American society have promoted a culture of business and excessive work to find meaning and have characterized self-care as a sign of weakness or failure.

Compounding these risks for graduate students, interns, and early career psychologists is managing numerous demands on a tight timetable (Pakenham & Stafford-Brown, 2012). Research, teaching, and clinical responsibilities must be balanced with personal life tasks. Ironically, these numerous pressures can increase the likelihood of feeling overwhelmed by CF symptoms and lead to potentially problematic behaviors, such as procrastination. Clinicians should carefully consider barriers to self-care for each individual presenting with CF. When implementing coping skills with a client with CF, identifying current resources is critical. Some factors to consider are time availability, socioeconomic status, insurance limitations, social supports, transportation, intersectional identities, and spiritual connectedness. Considering the culture embedded within some training programs or workplaces, identifying individuals to whom clients can dependably reach out is crucial for addressing CF.

Clinicians should consider the potential for negative professional impacts when assisting a client in identifying supports to address CF. For instance, a graduate student who identifies a psychologist at a training site as a potential support should consider the possibility for negative impacts on career trajectories. Safe social supports may come in the form of peer groups or peer supervision. While peers are at the same level of training, they may not always be a safe contact for a client to share issues related to CF. Competitiveness, jealousy, and personality differences within any given peer group may eliminate the usefulness of such peer support, so it is important for clinicians to carefully address the use of peer groups when identifying sources of support for those reporting CF.

In the opening vignette, Jada reports feeling isolated in her new location, which may be impacted by issues of race and culture. The clinician should explore Jada’s experience as a Black woman in her professional and personal life during internship. Understanding her current and previous experiences within an intersectional context may reveal additional barriers, coping skills, supports, or resources. For example, Jada has not yet explored Methodist churches in the area, yet she discussed this as an important part of her success in graduate school. She indicates she found meaning and value in her life outside of work when she volunteered through her previous church to provide food to those in need.

Whenever possible, psychologists should seek additional resources and training when working with clients who have intersectional identities outside of the psychologist’s expertise. If, however, this is not possible, psychologists should cultivate humble curiosity around the client’s intersectional experiences and explore the possibility of seeing a psychologist or therapist with this expertise. The exploration of seeing another therapist should be guided by the client as the client’s intersectional identities may or may not be prioritized in treatment. Further, the availability of therapists with such expertise may be limited in any given area.

Psychologists providing services to individuals within their field or in another human service profession are often faced with a unique ethical challenge. If a client’s symptom presentation is impacting their ability to provide care to others, one must consider the ethical responsibilities of everyone involved. First, an honest discussion with the client is warranted and their input on how to proceed must be carefully considered consistent with the American Psychological Association’s (APA; 2017) Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct, specifically 2.06 Personal Problems and Conflicts.

Tjeltveit and Gottlieb’s (2010) DOVE model of ethical decision-making is useful in this situation. It encourages psychologists to build resilience as a method of primary prevention for CF by identifying vulnerabilities and utilizing concrete skills prior to ethical challenges. In order to build resilience and identify vulnerabilities, psychologists should reflect upon their “Desire, Opportunities, Values, and Education” (DOVE). This framework provides practical dimensions to consider prior to ethical conundrums; however, it can be used during ethical dilemmas as well. If the clinician with CF and their mental health provider determine that a break from providing treatment is warranted, careful, planned steps should be taken for the clinician with CF to terminate services or transfer their clients while following the rules and guidelines of ethical practice within their clinical setting. Supervisors and other designated officials should also be included throughout the process. Additional options include cutting down on the number of clients or changing the type of clients (if possible) for the clinician with CF to work with.

A more difficult situation arises if the clinician with CF and their mental health provider disagree over their ability to provide care. Section 1.05 of the Ethical Principles of Psychologists (APA, 2017) inform the psychologist to take additional measures if we believe an ethical violation has not been resolved. This principle is further complicated by privacy rights. Since the clinician with CF in question has the right to confidentiality, only the most egregious behavior may warrant violating confidentiality without consent. Resolving ethical issues is not always a straight line, and the Ethical Principles suggest looking to the literature and consulting with experts in the field for additional guidance (e.g., Tjeltveit & Gottlieb, 2010).

Evidence-Based Assessment and Practice Recommendations

Assessment of pre-professionals and professionals who present with symptoms of CF should be guided by evidence-based assessment. Specific tools assessing for CF are available—most notably the Professional Quality of Life (ProQOL; Stamm, 2009) survey, a 30-item self-report that provides three subscales. These subscales—Burnout, Secondary Traumatic Stress, and Compassion Satisfaction—represent the main components of CF. The use of the ProQOL is free and the scoring is readily available on the website, as are interpretation guidelines and norms. Clinicians could easily use this as a measure of change over time.

Self-care may be informally or formally assessed by clinicians. However, it is important to get an indication of current self-care practices. There are a limited number of self-care measures, and none are without drawbacks. The Self-Care Assessment Worksheet (SCAW; Saakvitne et al., 1996) is one such tool, which assesses six different areas of self-care; however, its length may be unwieldy for practice. Despite this, the SCAW domains (physical, psychological, emotional, spiritual, professional workplace, and balance) and individual questions could be used as a guided interview to thoroughly probe for current self-care activities. Additional measures of self-care include the Self-Care Behavior Inventory (SCBI; Santana & Fouad, 2017) and the Self-Care Assessment for Psychologists (SCAP; Dorociak et al., 2017). To our knowledge, previous self-care instruments primarily address self-care activities. Therefore, Schwanz and Paiva-Salisbury (in press) developed the Self-Care Beliefs Scale (SCBS). A short 12-item measure that assesses for problematic ingrained beliefs about self-care, such as “I feel guilty when I take time for myself.” Whichever method the clinician chooses, the assessment of self-care practices and potentially problematic ingrained beliefs about self-care should help to guide evidence-based treatment. Table 1 provides a list of potentially relevant assessment measures for clients presenting with symptoms of CF.

Additional assessments may need to be considered on a case-by-case basis. CF has been strongly and positively associated with numerous other mental health concerns including depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, and substance abuse concerns (Drury et al., 2014; Figley, 2002; Gentry, 2002). Therefore, clinicians should use evidenced-based screening instruments for these concerns. While there are a wide variety of screening tools, the SCL-R 90 (Derogatis & Savitz, 1999) may be utilized as a broadband screening instrument. Alternatively, clinicians may choose to use evidenced-based screening tools currently employed in their practice.

Recommended Interventions for Compassion Fatigue

As a first line of defense for CF, prevention is the primary recommendation (Tjeltveit & Gottlieb, 2010). In line with this, psychologists who work with individuals exposed to trauma should continuously self-monitor for CF symptoms. Ideally the organizations they work with will provide regular education and training regarding the importance of building a self-care routine. Many clinics that provide services to traumatized populations already incorporate these elements into their sites. However, the organization should continuously monitor the need for additional supports for whom they are training.

Directors and supervisors of trainees should consider workload, additional duties outside the clinic, and outside stressors on the trainees. Pre-professionals are not in a position of power and may be reluctant to advocate for needed cultural changes within institutions. Administrators should also consider implementation of rotations, access to additional benefits, and advocacy efforts as part of their roles (Tjeltveit & Gottlieb, 2010).

For Jada, it would be useful to explore current efforts at her training site and potential sources of professional self-care accountability partners in her internship site or graduate program. Since Jada is working in a trauma-focused treatment setting, her internship site should have education specific to CF, including ways to monitor and manage symptoms of CF. Supervisors at the site should normalize and model these skills as essential for providers of trauma-related therapy. Supervisors should consider the balance of clients the interns are treating to manage the exposure to STS. Some interns may cope with STS well, but this can change unexpectedly. Therefore, it is imperative for Jada to consistently have open and frank discussions regarding CF in her internship. The site can encourage a culture of support among interns by offering regularly scheduled group outings or activities. Notably, the interns should be included in the planning of these activities to have a broad representation of activities and interests.

Clinicians may use a variety of evidenced-based practices to assist psychologists who present with symptoms of CF. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT; e.g., Forbes, 2020) and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT; Hayes et al., 2009) have a strong evidence base in treating symptoms related to stress, posttraumatic stress, depression, anxiety, and occupational stress (e.g., Forbes, 2020). The main aims in treating CF can be broadly considered in the following dimensions: awareness of CF, identification of current self-care, problematic thinking and behavioral patterns, skill building, barriers and problem solving, and planning ahead. From the ACT perspective, clinicians are assisting psychologists presenting with CF in building the psychological flexibility that provides resilience to professional stressors and secondary traumas. In the case of Jada, the clinician who currently utilizes ACT considers a short, focused treatment providing Jada with concrete skills, practices, and a flexible self-care plan. One may also consider using ACT at Work (Bond & Hayes, 2002), which is a manual of common ACT techniques for occupational stress.

While the individual components of burnout and STS are discussed distinctly in the literature, CF is typically a mixture of these symptoms. Education about CF, including the common signs and symptoms (detailed above), often provides the psychologist presenting with CF with a sense of relief or the feeling of not being alone (Forbes, 2020). Jada has recently learned of CF at a workshop; therefore, the clinician encourages Jada to reflect on what she learned. Jada is encouraged to identify her current self-care practices and any associated beliefs about self-care. She reports her current time demands as preventing her from practicing self-care. In addition, she feels guilt regarding the lack of time spent with her boyfriend.

CF often involves STS, which can create a sense of detachment outside of the professional environment. Mindfulness practices are well suited to assist individuals in connecting with their personal lives again and creating psychological distance from problematic thoughts. The clinician introduces a short mindfulness-based practice, Leaves on a Stream (Harris, 2019), which Jada can practice at home. Acceptance component of ACT provides the individual with an opportunity to integrate difficult emotions into their experience (Harris, 2019; Hayes et al., 2009) and can be used in real time during stressful and traumatic events (e.g., Quartana & Burns, 2007). The clinician guides Jada in imaginary practice of evidence-based ACT acceptance strategies while listening to veterans’ trauma narratives. Jada further considers managing STS symptoms by discussing her current caseload with her supervisor, which is practiced in vivo.

Evidence-based acceptance practices can likewise happen after a difficult event, or to cope with a difficult feeling. Burnout often leads to irritability and emotional exhaustion while at work, which may be accompanied by uncharacteristic feelings of not caring or anger at those we are treating. The clinician assists Jada to identify her feeling of shame, which is frequently accompanied by the thought, “Do I really know what I am doing?” The clinician uses an ACT-based guided acceptance meditation in session with a focus on the feelings of being inadequate as a clinician. It is critical to remind the client (and yourself) of the nonjudgmental stance of the ACT perspective (Hayes et al., 2009). Jada identifies a routine of breathwork and a brief focused meditation, which she will use to center prior to meeting with clients.

These dimensions of ACT are flexible and may be modified in order, although education is typically a good place to start. The aim is to develop a pragmatic yet flexible resilience building plan. Clients should identify a person who can hold them accountable to implementing these strategies and honestly reflect with them when they are taking on too much. Using ACT principles, Jada lays out values, commits actions connected to four of her dearly held values, and identifies a peer from her graduate program as an accountability buddy. In keeping with ACT, clinicians should consider providing clients with recorded meditations or provide them with concrete resources for these exercises. Notably, ACT’s focus on values can assist clients in building resilience to CF. Jada reconnects with her values of compassion for those in the military and contribution to her community. Through this self-reflection, she recommits to her professional goals and identifies a church in her current community to foster new connections and opportunities to volunteer.

Conclusions and Lessons Learned Relating the Vignette

The overarching goal of spreading awareness about compassion fatigue is to emphasize the critical importance of recognizing the characteristics and symptoms associated with CF before it becomes detrimental to a psychologist’s personal and professional well-being. Because some of the signs of CF can mimic and overlap with other issues, individuals may not consider CF to be a possible cause of one’s distress. Lack of knowledge about CF and additional risk factors may lead those who work with pre-professionals and helping professionals to overlook CF as a cause for debilitating symptoms.

We believe that one of the reasons why CF may not receive the attention it needs, particularly in the clinical field, is that it is not a diagnostic category but instead a descriptive term used among researchers, educators, and professionals from diverse fields of expertise. However, perhaps due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers, first responders, and others in helping professions the phenomenon of CF may be gaining more widespread attention. Schwanz and Paiva-Salisbury (in press) argue the importance of expanding the awareness and research about CF to trainees, such as graduate students, interns, residents, and even to undergraduates, who have yet to enter the workforce but often work in challenging roles with clients. We contend starting as early as possible in one’s career is a key to prevention and building resilience to compassion fatigue.

Given the evidence of the detrimental effects of CF, we concur with Barnett and Cooper (2009) regarding the ethical imperative to provide this support to our trainees and students. The ethical imperative is the responsibility of the administrators, directors, and supervisors to model appropriate self-care and advocate for those with less power in the field. Clinical training programs and internship sites would be wise to include resources and formal training around psychological well-being and resilience related to CF. The mental health of our workforce needs advocacy, and those responsible for making decisions at training sites have a powerful voice in how these decisions are made. An example is ensuring trainees have access to mental health care through the insurance offered at the training site. This issue, while not the focus of this paper, has important diversity and equity ramifications. Resource challenges may be especially important for diverse trainees and students. As we focus on increasing diversity, equity, and inclusion in our training and academic centers, one step we can take is to increase access to resources and opportunities by all trainees and pre-professionals. Further, we should constantly evaluate areas of concern and stress, such as the financial stressors of being a trainee, with an eye to providing equal access and inclusion for those who may have additional barriers.

Psychologists who find themselves treating fellow professionals should utilize their existing toolkit of evidenced-based treatments and assessments to treat CF. Oftentimes, existing assessments may be employed to monitor for symptoms of depression, stress, anxiety, and problematic substance use associated with CF. The existing literature on evidenced based treatment for the management of workplace stress and trauma is a great primer for treating individuals who present with CF. The psychologist should consider the ethical dilemmas with those presenting with CF more carefully prior to and during treatment and take additional precautions with graduate students and trainees who may not fully consider professional ramifications. Additionally, psychologists should be aware of resources available in the community including trainings and webinars on CF. These resources can assist both in treating CF and creating a flexible self-care plan, which includes life-long learning.

While teaching psychological resilience to graduate students, interns, and other pre-professionals is crucial to the future health of our workforce, we should also monitor ourselves for signs and symptoms of CF. Workplace stress has been increasing for decades in the United States (Richardson, 2017). The COVID-19 pandemic has given us an opportunity to focus on our values. There are currently numerous studies of ways to assist ourselves in leading more healthy lives, such as regular mindfulness practices, the importance of sleep, limiting the overwhelming number of choices in our daily lives, and regular exercise (e.g., Khoury et al., 2015). We can also take concrete actions by identifying opportunities to increase our own psychological well-being through education, connecting with peers, and seeking supervision. Peer supervision can be a useful place to share feelings of stress, fatigue, and burnout. Further, psychologists should identify a qualified accountability buddy among their peer group with whom they can honestly reflect on their current workload, especially during times of increased stress. Both accountability partners will benefit from hearing about common stressors in their practice and will also develop ideas for cultivating resilience to CF. Promoting psychological well-being in ourselves and others is a valued action we can all commit to today and every day.

Key Clinical Considerations

-

Prevention is a first line of defense to CF. Psychologists who work with individuals exposed to trauma should continuously monitor themselves for CF symptoms and encourage others to do the same.

-

Lack of awareness of CF. As CF is not an official psychiatric diagnosis, a lack of awareness can lead to development of more serious psychological symptomatology.

-

Pre-professionals and early career professionals have unique risks. Graduate students, interns, and early career professionals are often managing numerous demands on a tight timetable with few resources.

-

Psychologists have an ethical imperative to advocate for culture change. As psychologists, we have the power to advocate for those in training, and to create a culture where education, self-care, and well-being promotion are celebrated.

-

Clinicians should carefully consider diversity and individual differences related to self-care. When implementing coping skills with a client, consider the client’s diversity factors including intersectional identities and spiritual connectedness, socioeconomic status, social supports, and current resources related to time, insurance, and access to transportation.

References

American Psychological Association. (2017). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct (2002, amended effective June 1, 2010, and January 1, 2017). http://www.apa.org/ethics/code/index.html

Barnett, J. E. & Cooper, N. (2009). Creating a Culture of Self-Care. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 16(1), 16–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01138.x

Bond, F. W. & Hayes, S. C. (2002). ACT at work. Handbook of Brief Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 117-140.

Carlson, E.B., Smith, S.R., Palmieri, P.A., Dalenberg, C.J., Ruzek, J.I., Kimerling, R., Burling, T.A., & Spain, D.A. (2011). Development and validation of a brief self-report measure of trauma exposure: The Trauma History Screen (PDF). Psychological Assessment, 23, 463-477. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022294. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/articles/article-pdf/id36790.pdf

Derogatis, L. R., & Savitz, K. L. (1999). The SCL-90-R, Brief Symptom Inventory, and Matching Clinical Rating Scales. In M. E. Maruish (Ed.), The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment (pp. 679–724).

Dorociak, K. E., Rupert, P. A., Bryant, F. B., & Zahniser, E. (2017). Development of a Self-Care Assessment for Psychologists. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64(3), 325-334.

Drury, V., Craigie, M., Francis, K., Aoun, S. & Hegney, D.G. (2014). Compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, anxiety, depression and stress in registered nurses in Australia: Phase 2 results. Journal of Nursing Management, 22, 519–531.

Figley, C. R. (1995). Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized. Brunner/Mazel.

Figley, C. R. (2002). Compassion fatigue: Psychotherapists’ chronic lack of self-care. Journal of Clinical Psychology/In Session, 58, 1433-1441. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.10090

Forbes. (2020). Effective treatments for PTSD : practice guidelines from the international society for traumatic stress studies. The Guilford Press.

Gentry, J. E. (2002). Compassion fatigue: A crucible of transformation. Journal of Trauma Practice, 1(3/4), 37-61.

Harris, R. (2019). ACT made simple: An easy-to-read primer on acceptance and commitment therapy. New Harbinger Publications.

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (2009). Acceptance and commitment therapy. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Joinson, C. (1992). Coping with compassion fatigue. Nursing, 22(4), 116-122.

Khoury, B., Sharma, M., Rush, S. E., & Fournier, C. (2015). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for healthy individuals: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 78(6), 519-528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.03.009

Ludick, M. & Figley, C. R. (2017). Toward a mechanism for secondary trauma induction and reduction: Reimaging a theory of secondary traumatic stress. Traumatology, 23(1), 112-123.

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job Burnout Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 397. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397

Pakenham, K. I. & Stafford-brown, J. (2012). Stress in Clinical Psychology Trainees: Current Research Status and Future Directions. Australian Psychologist, 47(3), 147–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-9544.2012.00070.x

Quartana, P. J., & Burns, J. W. (2007). Painful consequences of anger suppression. Emotion, 7(2), 400–414. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.7.2.400

Richardson, K. M. (2017). Managing Employee Stress and Wellness in the New Millennium. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 423–428. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000066

Rupert, P. A. & Dorociak, K. E. (2019). Self-care, stress, and well-being among practicing psychologists. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 50(5), 343–350. https://doi.org/10.1037/pro0000251

Saakvitne, K. W., Pearlman, L. A., & Staff of the Traumatic Stress Institute (1996). Transforming the pain: A workbook on vicarious traumatization. Norton

Santana, M. C. & Fouad, N. A. (2017). Development and validation of a self-care behavior inventory. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 11(3), 140-145.

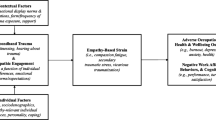

Schwanz, K. A. & Paiva-Salisbury, M. L. (In press). Before they crash and burn (out): A compassion fatigue resilience model in pre-professionals. Journal of Wellness.

Stamm, B.H. (2010). The Concise ProQOL Manual, 2nd Ed. Pocatello, ID: ProQOL.org.

Stamm, B. H. (2009). Professional Quality of Life: Compassion Satisfaction and Fatigue (Version 5). Pocatello, ID: ProQOL

Tjeltveit, A. C., & Gottlieb, M. C. (2010). Avoiding the road to ethical disaster: Overcoming vulnerabilities and developing resilience Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice Training, 47(1), 98. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018843

Willard-Grace, R., Knox, M., Huang, B., Hammer, H., Kivlahan, C., & Grumbach, K. (2019). Burnout and health care workforce turnover. The Annals of Family Medicine, 17(1), 36-41.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Paiva-Salisbury, M.L., Schwanz, K.A. Building Compassion Fatigue Resilience: Awareness, Prevention, and Intervention for Pre-Professionals and Current Practitioners. J Health Serv Psychol 48, 39–46 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42843-022-00054-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42843-022-00054-9