Abstract

A pilot cluster randomized controlled trial involving two HIV clinics in the Dominican Republic assessed preliminary efficacy of an urban garden and peer nutritional counseling intervention. A total of 115 participants (52 intervention, 63 control) with moderate or severe food insecurity and sub-optimal antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence and/or detectable viral load were assessed at baseline, 6- and 12-months. Longitudinal multivariate regression analysis controlling for socio-demographics and accounting for serial cluster correlation found that the intervention: reduced the prevalence of detectable viral load by 20 percentage points at 12 months; reduced any missed clinic appointments by 34 and 16 percentage points at 6 and 12 months; increased the probability of “perfect” ART adherence by 24 and 20 percentage points at 6 and 12 months; and decreased food insecurity at 6 and 12 months. Results are promising and warrant a larger controlled trial to establish intervention efficacy for improving HIV clinical outcomes.

Trial registry Clinical Trials Identifier: NCT03568682.

Resumen

Un estudio piloto de un ensayo controlado aleatorio por conglomerados que involucró a dos clínicas del VIH en la República Dominicana evaluó de forma preliminar la eficacia de una intervención de huertos urbanos y consejería nutricional entre pares. Un total de 115 participantes (52 de intervención, 63 de control) con inseguridad alimentaria moderada o grave y con adherencia subóptima a la terapia antirretroviral (TARV) y/o carga viral detectable fueron evaluados al inicio del estudio, y a los 6 y 12 meses. El análisis de regresión longitudinal multivariada controlando por variables sociodemográficas y tomando en cuenta la correlación serial de clúster encontró que la intervención: redujo la prevalencia de carga viral detectable en 20 puntos porcentuales a los 12 meses; redujo las citas clínicas perdidas en 34 y 16 puntos porcentuales a los 6 y 12 meses; aumentó la probabilidad de adherencia “perfecta” al TARV en 24 y 20 puntos porcentuales a los 6 y 12 meses; y disminuyó la inseguridad alimentaria a los 6 y 12 meses. Los resultados son prometedores y justifican un ensayo controlado más grande para establecer la eficacia de la intervención en mejorar los resultados clínicos del VIH.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Food insecurity, defined as “the limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate, safe foods or the inability to acquire personally acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways” [1, 2], remains a persistent barrier to achieving optimal HIV treatment outcomes. Across various settings, food insecurity is highly prevalent among people with HIV (PWH) [3,4,5,6,7] and is consistently related to antiretroviral therapy (ART) non-adherence [8], worse virologic and immunologic outcomes [9, 10], and higher morbidity [4] and mortality [11, 12].

Among interventions to address food insecurity among PWH, direct food support has been studied the most, and it has demonstrated positive effects on food security [13,14,15], as well as retention in care and adherence to treatment [4, 5]. However, providing supplemental food support is often not sustainable and fails to address the underlying causes of food insecurity. Further, such support has generally targeted PWH who are underweight [16], despite the growing burden of overweight and obesity among PWH [17]. A study in Honduras found that food assistance was effective in decreasing food insecurity among PWH but had the negative effect of weight gain among those who were overweight or obese at baseline [18].

Addressing chronic food insecurity and poor nutrition among PWH of diverse nutritional statuses requires food-generating activities integrated with nutrition education. Urban agriculture has strengthened capacity for sustainable livelihoods and food security among PWH in Kenya [19], while urban farming among PWH in the U.S. helped reduce psychological distress, social isolation, and risk behaviors and improve chronic disease-related behaviors [20]. A pilot cluster randomized controlled trial (RCT) in Kenya found that an agricultural intervention for PWH significantly increased CD4 cell counts and viral load suppression [21]. To our knowledge, none of these previous agriculture interventions with PWH have integrated comprehensive nutrition education, which may be important to support healthier food preparation and eating practices in conjunction with the increased food resources provided by the gardens. Nutritional education has been studied in conjunction with supplemental food support [22] but has typically been administered by professional nutritionists, who are often not available in most low-resource settings, limiting its scalability.

With this gap in mind, we developed an integrated urban gardens and peer nutritional counseling intervention to address food insecurity among PWH in the Dominican Republic (DR) who also had evidence of sub-optimal ART adherence and/or detectable viral load. Previous work in the DR found high levels of food insecurity (58% severe and 11% moderate) among PWH and significant associations between severe food insecurity and increased body mass index and body fat [23]. Our intervention, called ProMeSA (Proyecto para Mejorar la Seguridad Alimentaria/Project to Improve Food Security), aimed to reduce food insecurity among PWH of diverse nutritional statuses (underweight, normal, overweight, and obese) and thereby improve HIV clinic retention, ART adherence, and viral suppression. Our intervention was guided by a conceptual framework adapted from Weiser et al. [24], which outlines the pathways through which food insecurity affects viral suppression and other HIV outcomes including: (1) nutritional paths (e.g., dietary intake, ART side effects); (2) psychosocial paths (e.g., anxiety and depression, alcohol use, social support, and internalized HIV stigma); and (3) behavioral paths (e.g., ART adherence, clinic attendance).

The purpose of this paper is to report the preliminary efficacy of our urban gardens and peer nutritional counseling intervention on the primary outcomes, those being HIV care retention, ART adherence, and detectable viral load, as well as the primary target of our intervention, household food insecurity.

Methods

Partners

The pilot study was led by researchers at the RAND Corporation and the Universidad Autónoma de Santo Domingo (UASD), in partnership with the Dominican Ministry of Public Health, Ministry of Agriculture (Division of Urban Gardens), the Dominican National HIV/AIDS Council (CONAVIHSIDA), the World Food Programme, and researchers at the University of California, San Francisco.

Study Design

This pilot study is a cluster randomized controlled trial that explored preliminary efficacy of the ProMeSA intervention on food security and HIV clinical outcomes (HIV care retention, ART adherence, and detectable viral load). Two clinics were enrolled, one assigned to the treatment condition by randomly drawing one number from a pair of distinct numbers; the other clinic served as the usual care comparison (Clinical Trials Identifier: NCT03568682). Data were collected from enrolled participants at baseline and months 6 and 12 through interviewer administered surveys, chart abstraction and blood draws.

Setting and Recruitment

Together with CONAVIHSIDA partners, the study team identified 2 study clinics outside the capital that were of similar size (500–800 patients on ART), governance (government operated, to ensure similar standard of care), staff composition (1 primary care clinician, 2–3 nurses, at least 1 peer counselor) and in similar regions (northwest/central) yet far enough apart to avoid cross-contamination. The clinics were also in provinces with the country’s highest HIV prevalence. Women comprised roughly half the patients at each site.

Between May 2018 and January 2019, participants were recruited when they came to one of the two clinics for their routine appointments. Eligibility criteria included: (1) aged 18 + years; (2) registered at the HIV clinic and having been prescribed ART for at least 6 months; (3) evidence of ART adherence problems or lack of engagement in care (having missed at least one clinic appointment or ART refill in the past 6 months) and/or a detectable HIV viral load at most recent assay; (4) moderate or severe household food insecurity (see Food Security measure below); (5) resident of the catchment area of the clinic and an urban or peri-urban area; and (6) physically able to plant and maintain an urban garden (subjectively self-assessed by participants). The study was approved by institutional review boards of RAND, the UASD, and the Dominican Ministry of Public Health. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Intervention

The development of our novel, multi-component intervention—which used community-partnered research strategies involving local nutritionists, PWH, and other HIV stakeholders—is described fully elsewhere [25]. We summarize the various components below, which consisted of: (1) peer nutritional counseling; (2) urban gardening; and (3) a garden-based nutrition and cooking workshop.

Peer Nutritional Counseling

A culturally appropriate nutritional counseling curriculum with supportive visual aids and a reference technical manual was developed by the team nutritionists to assist in delivering the intervention in a standardized fashion. The curriculum was informed by previous work done with PWH in Honduras, first with professional nutritionists [22] and then transferred to peer counselors [15], as well as formative research conducted during the first phase of this study [26]. The curriculum covered the following topics: (1) consuming a balanced diet that includes all food groups; (2) increasing vitamin and mineral intake through a varied diet; (3) practicing food safety and hygiene; (4) eating a healthy diet without spending a lot of money; (5) managing potential side effects related to some ART medications, such as diarrhea, acute respiratory infections, nausea, mouth sores, and loss of appetite; and (6) understanding the role of nutrition in improving medication adherence and HIV outcomes.

HIV clinics in the DR have at least one adult peer counselor who supports clinic operations and provides outreach to patients who have suboptimal adherence. The peer counselor in the intervention clinic was trained by study personnel using a dynamic, participatory approach, i.e., active discussion and visual aids, followed by demonstrations and role-playing. Following classroom training, the peer nutrition counselor underwent in-service training in the clinical setting and agronomists helped the peer counselor start a home garden so that they could integrate first-hand experience with gardening into their nutritional counseling.

Once training was complete, the peer nutrition counselor provided nutritional counseling during participants’ regular visits to the clinic (3–4 sessions over 7–9 months). The nutritional counseling lasted about 30 min and was tailored to each individual, highly participatory, and designed to encourage participants to share concerns about food and eating and learn where to obtain certain foods and how to prepare them. The peer counselor shared their own experience about how eating a better diet has improved their quality of life and adherence and how to use products from the garden to do so. At the end of each session, participants identified steps they would take to apply the concepts learned in their daily lives, comments that peer counselors documented and reviewed at subsequent visits.

Urban Gardening

The Ministry of Agriculture, Division of Urban Gardens, routinely provides all seed, organic fertilizer, and equipment necessary to build and maintain gardens and has trained agronomists in each province. Agronomists worked with study personnel to schedule monthly group trainings and individual home visits to support participants in developing and maintaining home gardens. In addition, based on requests from participants, the project developed several community gardens for participants to grow food (especially for those who were not able to grow food at home); one was located adjacent to the HIV clinic where the study and intervention took place and two others were in communities where participants lived. The group trainings focused on the health benefits of vegetables, especially those grown without pesticides, and the basic requirements for establishing and maintaining a garden. In the home or communal garden visits, agronomists first evaluated the participants’ intended location for the garden, made recommendations, and provided tools. During subsequent visits, agronomists brought seeds and seedlings and provided additional technical assistance, including pest control and building fences to keep animals out. Agronomists visited participants to check on their progress; these visits were more frequent if the participant encountered any additional difficulties, had questions, or needed more tools or fertilizer.

Garden-Based Nutrition and Cooking Workshop

These workshops taught participants how to use garden produce and some basic rules for healthy and hygienic cooking. The workshop was highly participatory and incorporated information from the nutritional counseling sessions and how to prepare the garden produce to get maximum nutritional benefits. Participants worked together under the supervision of the nutritionist facilitating the workshop, helping to wash food, chop vegetables, and cook. The event culminated in a lunch with the food prepared in the workshop and participants received a booklet created by in-country collaborators that provided cooking tips and recipes.

Measures

Dependent Variables

Detectable viral load was determined through testing by the Dominican National Laboratory of Public Health using the Roche Cobas HIV-1 assay (Roche Molecular Diagnostics, Branchburg NJ, USA). Participants were coded “detectable” if viral load was ≥ 20 copies of HIV per mL of blood (reference group: undetectable viral load).

ART adherence and HIV care retention were measured using standard self-reported measures: (1) Participants rated their ART adherence ranging from 0 to 100% over the past month using a visual analog scale [27]; and (2) Participants were asked how many HIV appointments they had missed in the previous 6 months [28]. Given the tendency for self-report to overestimate adherence [27], a binary indicator of 100% adherence was used for each measure to define optimal adherence.

Food insecurity was measured using the validated Latin American and Caribbean Food Security Scale [29, 30], which assesses household food security over the past 90 days using 8 questions that cover relevant domains (worry, quality, and quantity), plus 7 additional questions for households with children < 18 years of age, and classifies households into 4 categories: “food secure” or “no food insecurity” (coded 0), “mild food insecurity” (coded 1), “moderate food insecurity” (coded 2) and “severe food insecurity” (coded 3).

Control Variables

Demographics. Participants were asked about their age (continuous), sex or gender (male/man, female/woman, transgender man, transgender woman, other), and self-identified nationality (Dominican, Haitian, or other), which was dichotomized as Haitian background versus none, given previous work showing that those with Haitian backgrounds in the DR disproportionately experience healthcare access barriers [31] and non-adherence to ART because of lacking food [32].

Poverty was defined as having a household income < 5000 pesos or approximately $100/month, or equivalent to the lower middle-income poverty line of $3.20 per day [33].

Number of children < 18 years of age in the household was asked, given the association between the number of children and household food insecurity [34].

Health insurance. Although HIV care is provided free of charge by the Dominican government, some expenses (e.g., medications for opportunistic infections, labs for chronic disease management, non-HIV care visits) are not, so we asked participants if they had health insurance (yes/no).

Analysis

Due to the small sample size in this pilot trial, we considered both the conventional statistical significance cutoff of 0.05 and the relaxed cutoff of 0.10 for two-sided p-values in all analyses. First, we conducted descriptive analysis to examine the differences between the two study clinics at baseline (Table 1) in detectable viral load, HIV care retention, ART adherence, food insecurity and control variables. We performed t-tests for continuous variables and Pearson’s Chi-squared tests for categorical or binary variables to examine the baseline differences due to clinic level randomization. The analyses were not blinded due to the small scale of this study and the cluster randomized controlled design. The study conditions of the two clinics were known to all study personnel and survey questions for the process evaluation exploring feasibility and acceptability of the intervention were included in the 12-month follow-up only for the intervention clinic participants (thus it is easily noted even in the data to which group that a study participant belongs). We reduced researcher bias through training and having multiple analysts examine the data independently.

The study was not designed to study mortality or survival during the study period. As such, death during the study period would make a participant ineligible and subsequently excluded from the primary statistical analysis. Based on the standard missing at random (MAR) assumption, we utilized all observed data from all eligible participants in statistical analyses. We also conducted sensitivity analysis in which those who died were included and outcomes recorded as “failure” (e.g., detectable viral load) for any measurements scheduled after their deaths.

Next, we performed difference-in-differences (DID) analyses (pre-specified in our proposal to the National Institutes of Health) to estimate the treatment effect at 6-month and 12-month follow up waves separately to differentiate short- and medium-term effects (Table 2). We anticipated that the DID analysis would be necessary given that we had only two clinics and therefore there was potential for significant baseline differences between the two, as observed in the descriptive analyses shown in Table 1. The DID analysis was operationalized through multivariate longitudinal linear regression models. Random effects were applied to account for serial cluster correlations among repeated measures within a participant.

We elected to use the mixed-effect linear model as opposed to mixed-effect logistic model for two reasons. First, the linear model has more intuitive interpretation, where the effect size is presented in the scale of absolute reduction or increase in risk rather than log odds ratio. Second, technically the linear model is more robust than the logistic model from both theoretical and computational perspectives [35], thus more suitable for this pilot study with a small sample size. We fitted two DID models for each outcome: a parsimonious model without controlling for any baseline covariates and an adjusted model controlling for baseline covariates, including participants’ socio-demographic characteristics (age, gender, education, Haitian background, health insurance status, poverty status, and number of children in the household).

Results

Figure 1 provides an overview of study screening, recruitment, enrollment, and follow-up. Of 345 adults screened, 138 were eligible [had moderate or severe food insecurity and sub-optimal antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence and/or detectable viral load] and 115 (52 intervention, 63 control) completed all baseline assessments and thus comprised the original analytic sample. After baseline and before 6-month follow-up, 4 participants passed away in the intervention clinic; of the remaining 111 participants, 108 (97%) completed 6-month follow-up. Two additional intervention participants passed away after 6-month follow-up and before 12-month follow-up; of the remaining 109 participants, 103 (94%) completed 12-month follow-up. For our analyses, we used all observed data, including those with only one or two waves of measurement and excluded data from 6 participants from the treatment arm who passed away; thus, our final analytic sample included 109 participants (46 intervention and 63 control).

Table 1 provides a comparison of the intervention and control clinics on key study variables at baseline. The overall sample was 44 years old on average, 47% were men, 16% self-identified as having Haitian background, 18% lived in poverty, 19% experienced moderate food insecurity while 81% experienced severe food insecurity, 61% had a detectable viral load, and the average years of formal education for all participants was between 5 and 6 (primary education). Statistically significant differences at the 0.05 level between the clinics were observed on participants reporting having health insurance (63% intervention clinic participants vs. 86% of control clinic participants), perfect adherence to ART in past month (35% of intervention participants vs. 60% of control participants) and having missed one or more HIV care appointments in past 6 months (54% of intervention participants vs. 14% of control participants).

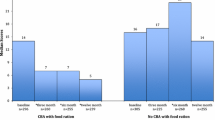

Table 2 provides the DID multivariable longitudinal linear regression results for the four outcomes of interest. Most of the covariates in adjusted models were insignificant, likely due to the limited statistical power. Using the adjusted models’ estimates, the intervention reduced the prevalence of detectable viral load by 19.5 percentage points at 12 months (z = − 1.89, p = 0.058); reduced any missed appointments in past 6 months by 33.5 percentage points at 6 months (z = − 3.63, p = 0.0003) and 16.0 percentage points at 12 months (z = − 1.72, p = 0.086); and increased the probability of taking 100% of ART medications in the past month by 24.4 percentage points at 6 months (z = 2.32, p = 0.020) and 19.7 percentage points at 12 months (z = 1.87, p = 0.062), compared to the control group. The intervention also decreased 4-point food insecurity scale (3 = severe food insecurity, 0 = no food insecurity) by 0.26 points at 6 months (z = − 1.84, p = 0.066) and 0.47 points at 12 months (z = − 3.32, p = 0.0009), respectively. The parsimonious models gave very similar point estimates compared with the adjusted models and slightly smaller p-values. Sensitivity analyses setting a participant’s outcomes for future measurements as “failure” (e.g., detectable viral load) after death had similar findings to the results in Table 2, but slightly smaller effect sizes and lower significance levels, since all six death events were in the treatment arm.

Discussion

In this pilot cluster RCT, we implemented a novel urban gardens and peer nutritional counseling intervention, which we developed through extensive formative research by a multi-sectoral partnership including PWH [7, 15, 23, 25, 26, 36] and drew on an established framework to delineate the relationship between food insecurity and HIV outcomes [24]. Several aspects of this study distinguish it from previous research. First, to our knowledge, no previous studies have assessed the impact on viral load of nutritional counseling in tandem with food-generating activities with PWH living with food insecurity. Given the importance of undetectable viral load for individual morbidity and mortality as well as prevention of HIV transmission, assessing impacts on viral load can contribute to advancements in both individual and population health. Second, our intervention addresses food security—an important social determinant of HIV-related outcomes—in a way that is replicable across diverse urban contexts and PWH of diverse nutritional statuses. As noted earlier, food supplementation for PWH has been the most studied but is often not sustainable (i.e., it often requires on-going provision and/or funding from an outside entity, many of which have time limits on the support they will provide); further, food supplementation has been shown to cause weight gain among overweight or obese PWH, increasing risk for cardiovascular disease [18]. Urban gardens, once established and maintained, can provide an ample and continuous supply of vegetables for the household, which are important sources of vitamins and minerals often lacking in the diets of food insecure PWH [7], as well as nourishing food to support ART medication adherence. Third, our intervention is delivered by peer lay workers; to date, there have been no published studies on the effectiveness of peer nutrition counselors on adherence or HIV outcomes among PWH; nutritional counseling, if offered at all, has been administered by professional nutritionists. Peer counselors represent a more affordable way of implementing these services in resource-constrained settings.

Most importantly, we found preliminary evidence of efficacy in reducing food insecurity and improving HIV clinical outcomes when intervention clinic participants were compared to usual care control clinic participants. Our findings extend the previous literature on interventions targeting food insecurity among PWH by demonstrating that an urban gardens and peer nutritional counseling intervention improved not only food security, but also ART adherence, HIV care retention, and virologic outcomes. This is promising given the persistently high levels of food insecurity, particularly severe food insecurity, among PWH and the negative effects on immunologic and virologic outcomes as well as ART adherence.

Previous work has found that among PWH in Latin America, approximately 60–70% have moderate or severe food insecurity [7], similar to levels seen among PWH in East Africa [21]. Thus, policies and programs that address food insecurity have the potential to optimize HIV treatment outcomes for large portions of PWH populations in resource poor-settings. It has been noted that the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated food insecurity, particularly for PWH [37]. Further, food insecurity and HIV have been identified as a “syndemic threat” and calls have been made to address the underlying reasons for food insecurity [38]. In the DR, this means addressing issues of poverty, social and economic inequality, job discrimination, weak agricultural structures, and recurring environmental shocks from climate change. Although our intervention does not address these larger structural issues, it does provide a way to improve access to and utilization of fresh fruits and vegetables, which are often lacking in diets of those experiencing food insecurity and contribute to low dietary diversity, including among PWH [39].

Given the tradeoffs that PWH often make in choosing between obtaining food for their families and obtaining healthcare [4, 40], strategies to address food insecurity among PWH need to be incorporated into ART treatment programs, particularly in low-resource settings and among low-income individuals in higher income settings. It is possible that our urban gardens and peer nutritional counseling intervention could have positive effects on management of other diet-sensitive health issues where food insecurity plays a role, such as diabetes, obesity and cardiovascular disease (CVD) [41] and mental health [42]. Such potential is promising given the growing burden of diabetes and CVD among PWH in the DR and globally, and the goal of comprehensive HIV care to encompass all aspects of well-being for PWH. There is also a growing recognition of the potential health and cost-savings benefits to integrate food and nutrition interventions into healthcare settings, often called “food is medicine” [43]. These interventions, which include medically tailored meals, medically tailored groceries, food “pharmacies,” and healthy food prescriptions, among other programs, are typically linked directly to the healthcare system and funded by healthcare, government, or philanthropy [44]; because of their cost, such strategies may be less sustainable in low-resource settings. Our urban gardens and peer nutritional counseling intervention presents a potentially lower-cost way to decrease food insecurity and improve health-related outcomes among vulnerable populations across diverse settings.

Limitations

As a small, pilot study, with only two clinics, we could not definitely separate intervention effects from cluster-level effects, highlighting the need for a larger trial. There were some significant baseline differences between intervention and control clinic participants, including two outcomes if interest (ART adherence and HIV care retention). In addition, our ART adherence and HIV clinic retention measures were self-reported and subject to recall and social desirability biases compared to objective measures of behavioral medication adherence such as mems. Coincidentally, our study recorded six deaths during the study period and all in the intervention arm, which might introduce a survivor bias in the model estimates. However, the overall retention rate was high and roughly balanced between the two clinics. Finally, given that we included only individuals who at baseline met criteria for moderate or severe household food insecurity, our findings do not generalize to all ART patients.

Conclusion

An urban garden and peer nutritional counseling intervention improved not only the most proximal outcome of food security, but also had positive effects on HIV care retention, ART adherence, and undetectable viral load. As a pilot study, our findings should be considered exploratory, hypothesis-generating, and as justification for a larger trial assessing efficacy. In addition, research is needed to assess pathways through which the intervention improves HIV outcomes, how to successfully scale-up the intervention, and how our intervention may improve outcomes for other health issues where food insecurity has a negative impact.

Data Availability

Because we did not state in the consent form that the data could be made available to outside researchers, our IRB has informed us that we cannot make the data available outside the study team.

References

Anderson SA. Core indicators of nutritional state for difficult-to-sample populations. J Nutr. 1990;120(Suppl 11):1555–600.

Ivers LC, Cullen KA. Food insecurity: special considerations for women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94(6):1740S-S1744.

Franke MF, Murray MB, Munoz M, Hernandez-Diaz S, Sebastian JL, Atwood S, et al. Food insufficiency is a risk factor for suboptimal antiretroviral therapy adherence among HIV-infected adults in urban Peru. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(7):1483–9.

Weiser S, Tsai AC, Gupta R, Frongillo EA, Kawuma A, Senkugu J, et al. Food insecurity is associated with morbidity and patterns of healthcare utilization among HIV-infected individuals in rural Uganda. AIDS. 2012;26(1):67–75.

Marcellin F, Boyer S, Protopopescu C, Dia A, Ongolo-Zogo P, Koulla-Shiro S, et al. Determinants of unplanned antiretroviral treatment interruptions among people living with HIV in Yaounde, Cameroon (eval survey, ANRS 12–116). Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13(12):1470–8.

Weiser SD, Tuller DM, Frongillo EA, Senkungu J, Mukiibi N, Bangsberg DR. Food insecurity as a barrier to sustained antiretroviral therapy adherence in Uganda. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(4): e10340.

Derose KP, Palar K, Farias H, Adams J, Martinez H. Developing pilot interventions to address food insecurity and nutritional needs of people living with HIV in Latin America and the Caribbean: an interinstitutional approach using formative research. Food Nutr Bull. 2018;39(4):549–63.

Singer AW, Weiser SD, Mccoy SI. Does food insecurity undermine adherence to antiretroviral therapy? A systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(8):1510–26.

Alexy E, Feldman M, Thomas J, Irvine M. Food insecurity and viral suppression in a cross-sectional study of people living with HIV accessing Ryan White food and nutrition services in New York City. Lancet. 2013;382:S15.

McMahon JH, Wanke CA, Elliott JH, Skinner S, Tang AM. Repeated assessments of food security predict CD4 change in the setting of antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;58(1):60–3.

Weiser SD, Fernandes KA, Brandson EK, Lima VD, Anema A, Bangsberg DR, et al. The association between food insecurity and mortality among HIV-infected individuals on HAART. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52(3):342–9.

Anema A, Chan K, Chen Y, Weiser S, Montaner JS, Hogg RS. Relationship between food insecurity and mortality among HIV-positive injection drug users receiving antiretroviral therapy in British Columbia, Canada. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(5): e61277.

Aberman NL, Rawat R, Drimie S, Claros JM, Kadiyala S. Food security and nutrition interventions in response to the AIDS epidemic: assessing global action and evidence. AIDS Behav. 2014;18:S554–65.

De Pee S, Grede N, Mehra D, Bloem MW. The enabling effect of food assistance in improving adherence and/or treatment completion for antiretroviral therapy and tuberculosis treatment: a literature review. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(Suppl 5):S531–41.

Derose KP, Felician M, Han B, Palar K, Ramirez B, Farias H, et al. A pre-post pilot study of peer nutritional counseling and food insecurity and nutritional outcomes among antiretroviral therapy patients in Honduras. BMC Nutr. 2015;1:8.

Kaye HL, Moreno-Leguizamon CJ. Nutrition education and counselling as strategic interventions to improve health outcomes in adult outpatients with HIV: a literature review. Afr J AIDS Res (AJAR). 2010;9(3):271–83.

Keithley JK, Duloy AM, Swanson B, Zeller JM. HIV infection and obesity: a review of the evidence. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2009;20(4):260–74.

Palar K, Derose KP, Linnemayr S, Smith A, Farias H, Wagner G, et al. Impact of food support on food security and body weight among HIV antiretroviral therapy recipients in Honduras: a pilot intervention trial. AIDS Care. 2015;27(4):409–15.

Karanja N, Yeudall F, Mbugua S, Njenga M, Prain G, Cole DC, et al. Strengthening capacity for sustainable livelihoods and food security through urban agriculture among HIV and AIDS affected households in Nakuru, Kenya. Int J Agric Sustain. 2010;8(1–2):40–53.

Shacham E, Donovan MF, Connolly S, Mayrose A, Scheuermann M, Overton ET. Urban farming: a non-traditional intervention for HIV-related distress. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(5):1238–42.

Weiser SD, Bukusi EA, Steinfeld RL, Frongillo EA, Weke E, Dworkin SL, et al. Shamba maisha: randomized controlled trial of an agricultural and finance intervention to improve HIV health outcomes. AIDS. 2015;29(14):1889–94.

Martinez H, Palar K, Linnemayr S, Smith A, Derose KP, Ramirez B, et al. Tailored nutrition education and food assistance improve adherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy: evidence from Honduras. AIDS Behav. 2014;18:S566–77.

Derose KP, Rios-Castillo I, Fulcar MA, Payan DD, Palar K, Escala L, et al. Severe food insecurity is associated with overweight and increased body fat among people living with HIV in the Dominican Republic. AIDS Care. 2018;30(2):182–90.

Weiser SD, Young SL, Cohen CR, Kushel MB, Tsai AC, Tien PC, et al. Conceptual framework for understanding the bidirectional links between food insecurity and HIV/AIDS. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94(6):1729s-s1739.

Derose KP, Fulcar MA, Acevedo R, Armenta G, Jiménez-Paulino G, Bernard CL, et al. An integrated urban gardens and peer nutritional counseling intervention to address food insecurity among people with HIV in the Dominican Republic. AIDS Educ Prev. 2021;33(3):187–201.

Wallace DD, Payán DD, Then-Paulino A, Armenta G, Fulcar MA, Acevedo R, et al. Perceptions and determinants of healthy eating for people with HIV in the Dominican Republic who experience food insecurity. Public Health Nutr. 2021;24(10):3018–27.

Simoni JM, Kurth AE, Pearson CR, Pantalone DW, Merrill JO, Frick PA. Self-report measures of antiretroviral therapy adherence: a review with recommendations for HIV research and clinical management. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(3):227–45.

Mugavero MJ, Davila JA, Nevin CR, Giordano TP. From access to engagement: Measuring retention in outpatient HIV clinical care. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010;24(10):607–13.

Melgar-Quiñonez H, Uribe MCA, Centeno ZYF, Bermúdez O, Fulladolsa PPD, Fulladolsa A, et al. Características psicométricas de la escala de seguridad alimentaria elcsa aplicada en Colombia, Guatemala y México. Segurança Alimentar e Nutricional. 2015;17(1):48–60.

Tsai AC, Bangsberg DR, Frongillo EA, Hunt PW, Muzoora C, Martin JN, et al. Food insecurity, depression and the modifying role of social support among people living with HIV/AIDS in rural Uganda. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(12):2012–9.

Keys HM, Kaiser BN, Foster JW, Burgos Minaya RY, Kohrt BA. Perceived discrimination, humiliation, and mental health: a mixed-methods study among Haitian migrants in the Dominican Republic. Ethn Health. 2015;20(3):219–40.

Derose KP, Han B, Armenta G, Palar K, Then-Paulino A, Jimenez-Paulino G, et al. Exploring antiretroviral therapy adherence, competing needs, and viral suppression among people living with HIV and food insecurity in the Dominican Republic. AIDS Care. 2021;8:1–9.

World Bank. Povery and equity brief: Dominican Republic. Washington: World Bank; 2020.

Nagata JM, Magerenge RO, Young SL, Oguta JO, Weiser SD, Cohen CR. Social determinants, lived experiences, and consequences of household food insecurity among persons living with HIV/AIDS on the shore of Lake Victoria, Kenya. AIDS Care. 2012;24(6):728–36.

Agresti A. Categorical data analysis. 2nd ed. Hoboken: Wiley; 2002.

Derose KP, Payan DD, Fulcar MA, Terrero S, Acevedo R, Farias H, et al. Factors contributing to food insecurity among women living with HIV in the Dominican Republic: a qualitative study. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(7): e0181568.

Mclinden T, Stover S, Hogg RS. HIV and food insecurity: a syndemic amid the COVID-19 pandemic. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(10):2766–9.

The Lancet HIV. The syndemic threat of food insecurity and HIV. Lancet HIV. 2020;7(2): e75.

Rebick GW, Franke MF, Teng JE, Gregory Jerome J, Ivers LC. Food insecurity, dietary diversity, and body mass index of HIV-infected individuals on antiretroviral therapy in rural Haiti. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(5):1116–22.

Palar K, Wong MD, Cunningham WE. Competing subsistence needs are associated with retention in care and detectable viral load among people living with HIV. J HIV AIDS Soc Serv. 2018;17(3):163–79.

Thomas MK, Lammert LJ, Beverly EA. Food insecurity and its impact on body weight, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and mental health. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 2021;15(9):15.

Trudell JP, Burnet ML, Ziegler BR, Luginaah I. The impact of food insecurity on mental health in Africa: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2021;278: 113953.

Mozaffarian D, Mande J, Micha R. Food is medicine-the promise and challenges of integrating food and nutrition into health care. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(6):793–5.

Downer S, Berkowitz SA, Harlan TS, Olstad DL, Mozaffarian D. Food is medicine: actions to integrate food and nutrition into healthcare. BMJ. 2020;369: m2482.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Dominican and Haitian participants who participated in the study, as well as clinic staff, especially the directors of the study clinics, Dr. Mirquella G. Rijo Ureña and Lcda. Chaira Rodríguez, and Dr. Johanny Tejada. We are grateful for the important technical support from the Ministry of Agriculture, especially Ing. Luis Eduardo Peña del Rosario, Leonardo Torres, Pedro P. Ovalle, and Luis A. Goris. We acknowledge the important and generous in-kind support from Dr. Susana Santos Toribio of the Nutrition Department of the Dominican Ministry of Health. Finally, we recognize the on-going assistance to ensure the study’s success from Dr. Víctor Terrero, formerly Executive Director of CONAVIHSIDA, and Dr. Ángel Díaz, formerly Director of Research of the Facultad de Ciencias de la Salud (School of Health Sciences) at the Universidad Autónoma de Santo Domingo.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R34MH110325. Dr. Palar and Ms. Sheira’s contributions were supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, University of California, San Francisco-Gladstone Institute of Virology & Immunology Center for AIDS Research, P30AI027763 (NIAID); additional funding for Dr. Palar was provided by K01DK107335 (NIDDK). The article contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KPD, GJW, BH, and ATP conceived the study. KPD, ATP, MAF, GA, RA, YD, KP, and LAS designed study materials. KPD, ATP, GA, and GJP supervised data collection. CL and IV contributed to data acquisition. KPD, ATP, GJP, RA, and MAF supervised intervention implementation. KPD, BH and GA analyzed the data with significant input from GJW, KP, and ATP. KPD wrote the first draft of the manuscript; BH, GA, GW, KP, and LAS made significant contributions to revisions. All authors contributed to interpretation of findings and have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the RAND Human Subjects Protection Committee and the internal review boards of the Universidad Autónoma de Santo Domingo (UASD) and the Consejo Nacional de Bioética en Salud (CONABIOS) of the Dominican Ministry of Public Health. The procedures used in the study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to Participate

Participants provided written informed consent.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Derose, K.P., Then-Paulino, A., Han, B. et al. Preliminary Effects of an Urban Gardens and Peer Nutritional Counseling Intervention on HIV Treatment Adherence and Detectable Viral Load Among People with HIV and Food Insecurity: Evidence from a Pilot Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial in the Dominican Republic. AIDS Behav 27, 864–874 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-022-03821-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-022-03821-3