Abstract

Background

Idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus (INPH) has no reliable biomarker to assist in the selection of patients who could benefit from ventriculo-peritoneal (VP) shunt insertion. The neurodegenerative markers T-tau and Aβ1-42 have been found to successfully differentiate between Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and INPH and therefore are candidate biomarkers for prognosis and shunt response in INPH. The aim of this study was to test the predictive value of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) T-tau and Aβ1-42 for shunt responsiveness. In particular, we pay attention to the subset of INPH patients with raised T-tau, who are often expected to be poor surgical candidates.

Methods

Single-centre retrospective analysis of probable INPH patients with CSF samples collected from 2006 to 2016. Index test: CSF levels of T-tau and Aβ1-42. Reference standard: postoperative outcome. ROC analysis assessed the predictive value.

Results

A total of 144 CSF samples from INPH patients were analysed. Lumbar T-tau was a good predictor of post-operative mobility (AUROC 0.80). The majority of patients with a co-existing neurodegenerative disease responded well, including those with high T-tau levels.

Conclusion

INPH patients tended to exhibit low levels of CSF T-tau, and this can be a good predictor outcome. However levels are highly variable between individuals. Raised T-tau and being shunt-responsive are not mutually exclusive, and such patients ought not necessarily be excluded from having a VP shunt. A combined panel of markers may be a more specific method for aiding selection of patients for VP shunt insertion. This is the most comprehensive presentation of CSF samples from INPH patients to date, thus providing further reference values to the current literature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus (INPH) is a condition that predominantly affects the elderly population, has a prevalence of 0.02%–5.9% and affects an estimated 2 million people within Europe [6, 10]. INPH presents with a triad of cognitive deficits, impaired mobility and incontinence. The mainstay of treatment is cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) diversion via a ventriculo-peritoneal (VP) shunt [1, 3]. Selection of patients for VP shunt insertion remains a challenge since the triad of symptoms in INPH is common in the elderly population. The surgery for a VP shunt is not without risk and a proportion of those with INPH do not benefit [16, 18]. Whilst prognostic tests are becoming more accurate, INPH still has no reliable biomarker to assist in the selection of patients for a VP shunt or for the monitoring of shunt function [7, 9, 15, 16, 18].

Tau and Aβ1-42 are well defined as CSF biomarkers that aid in the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and are potential prognostic markers in INPH [4, 8, 11,12,13,14]. Tau is a protein that promotes microtubule assembly and stability and is found in neuronal axons [4]. Aβ1-42 is a product of amyloid precursor protein (APP) that rapidly aggregates to form the main component of diffuse plaques [4]. The high CSF total-tau (T-tau) concentration is thought to reflect neuroaxonal degeneration/injury and low CSF Aβ1-42 correlates with senile plaque pathology [4, 8].

T-tau and Aβ1-42 levels have been found to successfully differentiate between AD and INPH [11, 12]. Patients with INPH consistently appear to have low CSF levels of T-tau and Aβ1-42 [8, 11,12,13,14]. A small subset of patients with INPH have raised T-tau levels on their initial lumbar samples, explained possibly by co-existing neurodegenerative disorder or a more progressive form of INPH [12]. It has been suggested that this subset of patients would be poor surgical candidates; however there is a paucity of literature describing outcomes in this group [12].

Over the last 10 years at this single centre, patients with probable INPH have had CSF samples analysed for total protein, T-tau and Aβ1-42 levels to investigate for co-existing neurodegenerative disease. Here we present the results of this large CSF sample cohort from INPH patients, including those with initial raised T-tau on their lumbar samples. We present the predictive values for lumbar and ventricular CSF T-tau and Aβ1-42 values for shunt responsiveness.

Materials and method

Study design

Single-centre retrospective analysis of probable INPH patients with CSF samples collected during August 2006 to January 2016. This study was reported in accordance with the STARD guidelines [5]. Clinical outcome (referenced standard), CSF samples analysis for T-tau and Aβ1-42 (index test) and radiological assessments were performed and recorded prospectively. The analysis of the data was performed retrospectively.

Inclusion

Eligible patients required a diagnosis of probable INPH from a single centre. Only those with samples taken prior to VP shunt insertion (initial diagnostic LP or LD) or during insertion if a VP shunt were included into the predictive analysis. Formal consent for cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) sample analysis and use of results for research (including publication) was obtained.

Exclusion

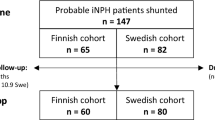

Exclusion criteria included loss to follow-up or death before follow-up. Those without prior lumbar drainage or lumbar puncture, or a poor response, were not fulfilling the international criteria for a diagnosis of probable INPH and therefore also not included in the ventricular predictive analysis (Fig. 1) [18]. These two groups were acknowledged in the demographic data and in the additional analysis.

Flow chart of patient participants. A total of 87 samples, 71 primary ventricular and 30 primary lumbar (from 65 patients), were included in the final predictive value analysis. Secondary samples (43) and samples from those with poor or no ELD/LP were included in the longitudinal analysis of markers in CSF drainage and in analysis of rostro-caudal gradients

Diagnostic criteria

Three forms of evidence, based upon the international criteria for the diagnosis of probable INPH, were used to aid selection of patients for VP shunt insertion [18]: (1) patients over 40 years of age with a clinical insidious history of the typical triad of cognitive decline, mobility impairment and urinary incontinence, (2) characteristic brain imaging (MR images or CT) showing an un-obstructive ventriculomegaly and (3) positive clinical response in either mobility or cognition or a reduction in episodes of urinary incontinence after extended lumbar drainage (ELD) or lumbar puncture (LP). Patients were deemed to have a diagnosis of co-existing neurodegenerative disease if they had objective evidence (clinical, radiological and biochemical) and formal diagnosis made independently by a consultant neurologist.

Index test: CSF analysis

CSF was sampled for T-tau and Aβ1-42 during any of the following interventions: LP, ELD or infusion study, VP shunt, VP shunt revision or reservoir tap test. Samples taken during the ELD protocol were taken at the time of drain or catheter insertion and not after a period of extended drainage. CSF samples were collected under sterile conditions into 10-ml Sartstedt polypropylene tubes. CSF sample collection and storage methods were all in accordance with the consensus guidelines for CSF biobanking [21]. Samples were sent for biochemical and enzyme-linked immunosorbent (ELISA) analysis to measure concentrations of T-tau (INNOTEST hTAU ELISA, Fujirebio, Ghent), Aβ-42 [INNOTEST β-amyloid (1–42), Fujirebio, Ghent] and total protein. A technician, blinded to the clinical results, prospectively recorded levels of T-tau and Aβ-42. Longitudinal stability in the measurements was ascertained using an elaborate programme of internal quality control (QC) samples. The laboratory also takes part in the Alzheimer’s Association external QC programme for CSF biomarkers [6]. Intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation were 12 and 15% for Aβ1-42, respectively, and 3 and 12%, respectively, for T-tau.

Reference standard: clinical outcome

The clinical outcome groups ‘shunt responsive’ or ‘shunt unresponsive’ provided the reference standard. Outcome measures were recorded prospectively and analysed retrospectively. Three main outcome objective measures were analysed: (1) Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale R (WAIS-R) neuropsychology report (any improvement observed in verbal IQ, performance IQ or full scale IQ), (2) timed 10-m walking test (a minimum of 5% improvement in either time in seconds or number of steps, or both) and (3) bladder control (with improvement being the reduction of episodes of incontinence per day of 1 or less). Assessments were done by personnel blinded to the index test result. For outcome analysis, an ‘improvement’ reflected better outcome in at least one of the three objective measures, in addition to reported subjective improvement. A deterioration in any one of these clinical elements resulted in an overall outcome of ‘no improvement’. All outcome data were processed on an anonymous database.

Statistical analysis

Sample means and variation: Samples were grouped into primary CSF collection (i.e. taken prior to the shunt) and secondary (i.e. taken to test the functioning of a shunt or as part of a revision surgery). Mean levels of T-tau and Aβ-42 were reported with standard deviation. Mean levels were compared between the various sample collection groups (lumbar vs. primary ventricular vs. secondary ventricular) using analysis of variance (ANOVA with a Geisser-Greenhouse’s epsilon correction). Linear regression analysis was performed to determine the effect of age on T-tau and Aβ-42 levels.

Exploratory analysis: ROC analysis was used to assess predictive values for overall shunt responsiveness, mobility, cognition and urinary continence. Area under the ROC (AUROC) levels were implied to suggest the predictive valve of a test as the following: 0.80–0.90 = good, 0.70–0.79 = fair, 0.60–0.69 = poor and 0.50–0.59 = no differentiation. Optimal cut-off values derived from ROC analysis are presented with 95% confidence intervals.

Pre-specified analysis: Contingency tables presenting the negative and positive predictive values (NPV and PPV), sensitivity and specificity of T-tau and AB1-42 were then determined using the following published cut-off values for INPH: T-tau protein levels < 425.7 ng/l ± 244.3, Aβ-42 > 500 ng/l and a ratio of T-tau to Aβ-42 of <1 [17]. This was repeated using the ROC calculated optimal cut-off values. All values were expressed as percentages with ‘exact’ Clopper-Pearson confidence intervals with Fisher’s exact test results. All statistical tests were performed in GraphPad Prism v6.0.

Results

Study profile

August 2006 to January 2016, a total of 144 CSF samples were analysed from 79 probable INPH patients: 31 females:48 males (31 F:48 M) of mean age 75.3 (R 55–94). Mean follow-up was 959 ± 657 days (mean ± SD). Figure 1 outlines the study profile.

Demographics

The frequency of clinical characteristics in both the shunt responsive and non-responsive groups is demonstrated in Table 1. There was no significant difference in the frequency of co-morbidities (Table 1).

T-tau levels and Aβ-42 ratio levels correlated with increasing age on linear regression analysis. When the results from the three patients under the age of 60 were excluded from the analysis, this correlation was no longer significant (p = 0.09, R2 = 0.04). The three patients under the age of 60 were included in the full analysis.

The mean duration of the symptoms of INPH prior to CSF analysis was 290.5 ± 491.1 days. The mean time to VP shunt insertion after LP or LD was 226.9 ± 218.7 days. The mean time from VP shunt insertion to reservoir tap test was 739.1 ± 325.5 days.

Neurodegenerative disease

Fourteen patients had a post-operative neurodegenerative diagnosis (5 Parkinson’s disease, 5 AD, 3 Lewy-body dementia and 1 frontal-temporal lobe dementia). The presence of a neurodegenerative diagnosis did not significantly affect outcome (Table 1). Eleven of 14 patients with a neurodegenerative diagnosis were still shunt responsive.

Mean levels per site

Mean levels of Aβ1-42 and T-tau per sampling method are presented for INPH and INPH patients with a co-existing neurodegenerative disease (Table 2). The range of T-tau levels in primary lumbar CSF varied from 68 to 872 ng/l and from 56 to 2085 ng/l in primary ventricular samples. Aβ1-42 levels ranged from 111 to 911 ng/l in lumbar samples and 100–1231 in primary ventricular samples. Mean CSF levels of T-tau in samples taken during LP or LD were significantly lower than in the samples seen during VP shunt insertion (p = 0.001).

ROC analysis of T-tau and Aβ-42 and shunt response

AUROC for lumbar CSF levels of T-tau was 0.6, for T-tau/Aβ-42 0.62, respectively, with Aβ-42 being 0.5. The AUROC for ventricular CSF levels of T-tau, Aβ-42 and T-tau/Aβ-42 were 0.70, 0.51 and 0.64, respectively.

The analysis of lumbar and ventricular samples was repeated for the individual components of outcome: mobility, cognition and urinary continence. T-tau and Aβ-42 levels in both lumbar (Fig. 2a–c) and ventricular samples (Fig. 2d–f) were poor predictors of outcome, with the exception of lumbar T-tau for predicting improvement in mobility. Lumbar CSF T-tau had an AUROC of 0.84 (p = 0.04), making it a potentially good predictor of mobility outcome (Fig. 2). Although graphically ventricular T-tau and urinary continence outcome appears promising, with an AUROC of 0.78, the result is not significant (p = 0.19).

ROC curve demonstrating ability CSF levels of T-tau, Aβ1-42 levels and the ratio T-tau/Aβ1-42 to predict improvement in the triad of symptoms a–c lumbar primary CSF a mobility (n = 21), b cognition (n = 13) and c continence (n = 5). d–f Ventricular primary CSF d mobility (n = 36), e cognition (n = 17) and f continence (n = 9)

Predictive values for T-tau and Aβ-42 and shunt response

Optimal predictive cut-off values derived from ROC analysis for T-tau in lumbar samples were < 196.5 ng/l and < 525 ng/l in ventricular samples. The predictive values of degenerative markers in lumbar CSF and ventricular CSF are presented in Tables 3 and 4, respectively.

Complications

One patient developed an infection as a result of a clinically indicated reservoir tap test. This patient was treated with intravenous antibiotics. There were no mortalities associated with CSF sampling.

Discussion

Mean T-tau and Aβ1-42 levels in the CSF of patients with probable INPH

We have performed a singe-centre analysis of T-tau and Aβ1-42 levels in the CSF of patients with probable INPH. This is one of the most comprehensive presentations of CSF samples from INPH patients to date, thus providing further reference values to the current literature [2]. The mean lumbar CSF levels of T-tau in INPH were found to be lower than levels expected in normal controls, a finding observed in several studies [8, 11, 13]. We also confirmed previous findings of a rostro-caudal gradient with significantly lower levels of T-tau in lumbar CSF than in ventricular CSF [19]. Regardless of the sampling method, the range for both markers was wide, particularly T-tau, and therefore the authors recommend caution when interpreting their levels in the context of prognosis for individual patients.

The predictive value of Aβ1-42 and T-tau for shunt response in INPH

Ventricular Aβ1-42 and T-tau have previously been demonstrated to be potentially clinically useful biomarkers for prognosis in INPH [20]. The AUROC values for ventricular T-tau (general post-shunt outcome) and lumbar T-tau (mobility outcome) were 0.70 and 0.80. This result concurs with the findings by Kang et al. in which low levels of tau correlated with gait dysfunction [13]. Kang et al. also found that lower levels of Aβ1-42 correlated with poor cognitive outcome in INPH; however our results did not mirror this, possibly due to low numbers within this sub-group [13].

The observation that lumbar samples have a better predictive value than ventricular samples is interesting. One possible explanation may relate to the hypothesis that tau has reduced clearance in INPH, hence lower levels in CSF [8]. Therefore lumbar CSF T-tau levels may be even lower, owing to the greater distance from metabolically active tissue, thus exaggerating the predictive value.

Patients with raised T-tau CSF can still benefit from shunt insertion

Current literature emphasises differentiating INPH and AD; however there are patients with NPH and neurodegenerative disease co-existing [8, 12, 14]. Patients with clinical signs of INPH may not be referred for neurosurgical assessment, if co-existing neurodegenerative disease is present, as it is assumed to render surgical intervention ineffective [12]. Our results show that assumption is not necessarily correct. We found that the majority of those who had neurodegenerative disease coexisting with INPH were still shunt responsive, despite this group having, on average, raised T-tau on lumbar CSF samples. We conclude raised levels of T-tau and being shunt-responsive are not mutually exclusive, and patients with raised T-tau ought not to be excluded from having a VP shunt on this criterion alone.

Limitations

To control for the heterogeneity of our data, we analyse some of the samples in subgroups. As a result, the sub-group analysis of lumbar CSF samples (reviewing gait, cognition and continence) had reduced statistical power. The authors of this article are currently studying whether the individual CSF biomarker levels predict actual improvements (i.e. will 10% lower T-tau reflect a 20% improvement in walking speed). To get more meaningful results, greater numbers are required and therefore this is an ongoing element of this research.

Future research

Further research into discovery of biomarkers, or even a panel of markers, in INPH remains warranted. Since this study commenced there have been advances in biomarker discovery and there are now numerous potential biomarkers to be studied in INPH [2]. One example of an effective combination of markers includes Aβ1-42, neurofilament light protein (NF-L) and phosphorylated-tau (p-Tau), a promising panel to distinguish iNPH [2]. Furthermore, there are very few studies measuring levels of marker levels over time with CSF drainage. This group is currently studying how shunt insertion changes the CSF biomarker profile in an individual. Such research may further elucidate the pathophysiology of INPH as well as assist in identifying shunt malfunctions.

Conclusion

Raised levels of T-tau and being shunt-responsive are not mutually exclusive. This is highly relevant, since many units would have presumed such patients (i.e. those with Alzheimer’s disease and INPH) to be poor surgical candidates. In general, INPH exhibits low levels of CSF T-tau, and levels can be good predictors of outcome. However, we discourage diagnosis and outcome prediction based on T-tau levels alone, as its CSF levels are highly variable between individuals. It is likely that a combined panel of markers, including T-tau, will be a more specific method for aiding selection of patients for VP shunt insertion.

References

Adams RD, Fisher CM, Hakim S, Ojemann RG, Sweet WH (1965) Symptomatic occult hydrocephalus with "normal" cerebrospinal-fluid pressure. A treatable syndrome. N Engl J Med 273:117–126

Agren-Wilsson A, Lekman A, Sjoberg W, Rosengren L, Blennow K, Bergenheim AT, Malm J (2007) CSF biomarkers in the evaluation of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Acta Neurol Scand 116:333–339

Black PM (1980) Idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus. Results of shunting in 62 patients. J Neurosurg 52:371–377

Blennow K (2004) Cerebrospinal fluid protein biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. NeuroRx 1:213–225

Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, Gatsonis CA, Glasziou PP, Irwig L, Lijmer JG, Moher D, Rennie D, de Vet HC, Kressel HY, Rifai N, Golub RM, Altman DG, Hooft L, Korevaar DA, Cohen JF, STARD Group (2015) STARD 2015: an updated list of essential items for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies. Clin Chem 61:1446–1452

Brean A, Eide PK (2008) Prevalence of probable idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus in a Norwegian population. Acta Neurol Scand 118:48–53

Craven CL, Toma AK, Mostafa T, Patel N, Watkins LD (2016) The predictive value of DESH for shunt responsiveness in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. J Clin Neurosci 34:294–298

Graff-Radford NR (2014) Alzheimer CSF biomarkers may be misleading in normal-pressure hydrocephalus. Neurology 83:1573–1575

Hashimoto M, Ishikawa M, Mori E, Kuwana N, Study of INPH on neurological improvement (SINPHONI) (2010) Diagnosis of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus is supported by MRI-based scheme: a prospective cohort study. Cerebrospinal Fluid Res 7:18

Jaraj D, Rabiei K, Marlow T, Jensen C, Skoog I, Wikkelso C (2014) Prevalence of idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus. Neurology 82:1449–1454

Jeppsson A, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Wikkelso C (2013) Idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus: pathophysiology and diagnosis by CSF biomarkers. Neurology 80:1385–1392

Jingami N, Asada-Utsugi M, Uemura K, Noto R, Takahashi M, Ozaki A, Kihara T, Kageyama T, Takahashi R, Shimohama S, Kinoshita A (2015) Idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus has a different cerebrospinal fluid biomarker profile from Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 45:109–115

Kang K, Ko PW, Jin M, Suk K, Lee HW (2014) Idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus, cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers, and the cerebrospinal fluid tap test. J Clin Neurosci 21:1398–1403

Kapaki EN, Paraskevas GP, Tzerakis NG, Sfagos C, Seretis A, Kararizou E, Vassilopoulos D (2007) Cerebrospinal fluid tau, phospho-tau181 and beta-amyloid1-42 in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus: a discrimination from Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Neurol 14:168–173

Lieb JM, Stippich C, Ahlhelm FJ (2015) Normal pressure hydrocephalus. Radiologe 55:389–396

Malm J, Graff-Radford NR, Ishikawa M, Kristensen B, Leinonen V, Mori E, Owler BK, Tullberg M, Williams MA, Relkin NR (2013) Influence of comorbidities in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus - research and clinical care. A report of the ISHCSF task force on comorbidities in INPH. Fluids Barriers CNS 10:22

Mattsson N, Andreasson U, Persson S, Carrillo MC, Collins S, Chalbot S, Cutler N, Dufour-Rainfray D, Fagan AM, Heegaard NH, Robin Hsiung GY, Hyman B, Iqbal K, Kaeser SA, Lachno DR, Lleo A, Lewczuk P, Molinuevo JL, Parchi P, Regeniter A, Rissman RA, Rosenmann H, Sancesario G, Schroder J, Shaw LM, Teunissen CE, Trojanowski JQ, Vanderstichele H, Vandijck M, Verbeek MM, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Alzheimer’s Association QCPWG (2013) CSF biomarker variability in the Alzheimer’s Association quality control program. Alzheimers Dement 9:251–261

Relkin N, Marmarou A, Klinge P, Bergsneider M, Black PM (2005) Diagnosing idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus. Neurosurgery 57:S4–16 discussion ii-v

Tarnaris A, Toma AK, Chapman MD, Petzold A, Keir G, Kitchen ND, Watkins LD (2011) Rostrocaudal dynamics of CSF biomarkers. Neurochem Res 36:528–532

Tarnaris A, Toma AK, Chapman MD, Keir G, Kitchen ND, Watkins LD (2011) Use of cerebrospinal fluid amyloid-beta and total tau protein to predict favorable surgical outcomes in patients with idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. J Neurosurg 115:145–150

Teunissen CE, Tumani H, Bennett JL, Berven FS, Brundin L, Comabella M, Franciotta D, Federiksen JL, Fleming JO, Furlan R, Hintzen RQ, Hughes SG, Jimenez CR, Johnson MH, Killestein J, Krasulova E, Kuhle J, Magnone MC, Petzold A, Rajda C, Rejdak K, Schmidt HK, van Pesch V, Waubant E, Wolf C, Deisenhammer F, Giovannoni G, Hemmer B (2011) Consensus guidelines for CSF and blood biobanking for CNS biomarker studies. Mult Scler Int 2011:246412

Acknowledgements

We thank Mr. Andrew Tarnaris for his early research on this topic, which enabled this retrospective study.

Disclosure: Portions of this work were presented in abstract form at the Hydrocephalus 2016 International Society for Hydrocephalus and Cerebrospinal Fluid Disorders Conference, Cartagena, Colombia, October 2016. L.D. Watkins has received honoraria from and served on advisory boards for Medtronic, Codman and B. Braun.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

Mr. Watkins has received honoraria from and served on advisory boards for Medtronic, Codman and B. Braun.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

For this type of study formal consent is not required.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Craven, C.L., Baudracco, I., Zetterberg, H. et al. The predictive value of T-tau and AB1-42 levels in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Acta Neurochir 159, 2293–2300 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-017-3314-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-017-3314-x