Abstract

Purpose

Shared decision making (SDM) among the oncology population is highly important due to complex screening and treatment decisions. SDM among patients with cancer, caregivers, and clinicians has gained more attention and importance, yet few articles have systematically examined SDM, specifically in the adult oncology population. This review aims to explore SDM within the oncology literature and help identify major gaps and concerns, with the goal to provide guidance in the development of clear SDM definitions and interventions.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review using the Arksey and O’Malley approach along with the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews Checklist. A systematic search was conducted in four databases that included publications since 2016.

Results

Of the 364 initial articles, eleven publications met the inclusion criteria. We included articles that were original research, cancer related, and focused on shared decision making. Most studies were limited in defining SDM and operationalizing a model of SDM. There were several concerns revealed related to SDM: (1) racial inequality, (2) quality and preference of the patient, caregiver, and clinician communication is important, and (3) the use of a decision-making aid or tool provides value to the patient experience.

Conclusion

Inconsistencies regarding the meaning and operationalization of SDM and inequality of the SDM process among patients from different racial/ethnic backgrounds impact the health and quality of care patients receive. Future studies should clearly and consistently define the meaning of SDM and develop decision aids that incorporate bidirectional, interactive communication between patients, caregivers, and clinicians that account for the diversity of racial, ethnic, and sociocultural backgrounds and preferences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Treatment decisions in cancer care can be highly complex, particularly when options involve trade-offs between aggressive management and quality of life (QOL), often leading to high-stakes decisions within a context of uncertain treatment benefit [1]. As such, clinicians, patients, and patient advocates have long supported the idea of a shared approach to cancer decision making in which patients and clinicians discuss and arrive at a mutually acceptable and ideally optimal decision. Shared decision making (SDM) was originally defined as involving a minimum of two participants (patient and clinician) who work to build mutual trust through sharing of information and ultimately reach a consensus for a preferred treatment decision [2]. The concept is highly relevant to the cancer care continuum, along which there may be multiple occasions in which patients must select a course of treatment or plan of care [3].

Although the concept of SDM is recognized as being important and preferred in oncology within the USA, SDM has not become the standard practice [4, 5]. In some Eastern societies, there may be little patient decision-making involvement with a more prevalent paternalistic view of the patient-physician relationship [6]; whereas patients in the USA often are in high need of treatment information, and they have more satisfaction with the treatment they receive when they are involved in the decision-making process [7]. It has been noted that there may be differences between what the clinician may see as important versus what is the priority from the patient’s perspective [8]. In addition to potential barriers at the patient and clinician level, barriers at the US healthcare system structure level (i.e., clinician’s time with a patient’s visit linked with the payment model, clinician’s autonomy to implement decision aids) exist [9, 10].

Since SDM was initially introduced in the cancer literature, the application of SDM terminology has broadened, but there is not yet consensus around one definition of SDM or how to measure the concept [11]. In recent years, investigators have expanded the term to encompass decisions beyond treatment, applying the term more generically to guide patients and clinicians in a mutual decision on any course of action [12, 13]. Today, SDM is applied to research studying decision making ranging from cancer screening [14, 15]. to post-treatment symptom monitoring during cancer survivorship [16] and end-of-life decisions. [17].

Specific processes have been identified as essential to SDM, but investigators have not adopted a standard SDM model with defined action steps or elements [11]. Processes supporting open communication are a key element of SDM that have the potential to improve QOL due to their impact on patients’ knowledge and confidence in the partnership with the clinician [13], but no standardized measurement for communication quality is used [18]. Lack of measurement standardization has likely contributed to the inability to rigorously link high-quality SDM to patient outcomes; prior reviews of the literature have found a weak relationship between SDM and QOL due in part to studies using inconsistent methodologies. [19].

Within the context of an ill-defined process, interventions may be difficult to develop and measure. Much research has been devoted to developing decision aids (DAs), structured interventions that help patients and/or caregivers with clinicians engage in SDM to make informed decisions. DAs include videos, interactive mobile apps, or paper forms used to help clarify patient and family values, goals, hopes, and fears within the disease trajectory. DAs encourage active participation by patients in their own health decisions, which can potentially increase patient treatment adherence and satisfaction [20]. Although DAs have proven their utility, [21, 22]. they are just one potential part of the SDM process, and additional clinical interventions are needed to improve the SDM process for patients and link these interventions to improved outcomes (e.g., QOL, treatment satisfaction).

Given the critical need to understand and improve SDM between patients, caregivers, and clinicians, we conducted a scoping review to explore the existing evidence of the use of SDM in cancer care in the USA. There are few reports that have systematically examined SDM in the adult oncology population [23]. This scoping review was conducted with the goal to explore shared decision making within the US-based oncology literature to help identify major gaps, and to examine areas of concern regarding SDM. This review examines several aspects of SDM, including the implementation of SDM, the concept of SDM, and the level of SDM engagement. This paper has the potential to provide guidance in the development of clear SDM definitions and interventions that address key aspects of patients and/or their caregivers when making decisions about cancer care.

Methods

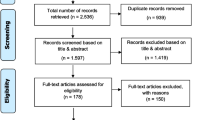

Scoping reviews are conducted to map the evidence broadly on a particular exploratory topic and to identify the concepts and/or knowledge gaps [24], thus making it more suited for our research question versus a systematic review that is more precisely focused and critically appraises studies. The methodological approach that guided our work was a modified Arksey and O’Malley framework for conducting scoping reviews [25]. The approach involved 5 steps: (1) a research question that was identified, (2) relevant studies were identified (systematic reviews were excluded due to duplications), (3) eligible studies were selected, (4) a chart was developed and used to extract each studies’ data, and (5) data were collated, summarized, and reported. Our approach was informed by utilizing the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines [24] (Fig. 1). The search strategy was developed in collaboration with a professional health sciences librarian.

Search strategy

Once the project team agreed on the keywords and controlled vocabulary, the librarian performed searches along with certain criteria in PubMed, CINAHL (academic journals), Web of Science (articles, reviews, early access), and PsycINFO (academic journals). A 5-year period from 2016 to 2021 was selected due to the rapid advancement in treatment management in cancer care. Cancer care and treatment delivery has changed rapidly over the years, due to the pace of scientific research and world events, such as the Covid-19 pandemic. Occasions such as time spent with patients were affected, and delays in cancer diagnosis/treatment [26, 27] may have affected the patient-clinician relationship and the SDM process. Due to evolving state of cancer care, we used a 5-year timeframe. Articles only in the English language were selected. Two main keywords were searched: “Shared Decision Making” and “Cancer.” Searches in the CINAHL, Web of Sciences, and PsycINFO databases were performed using keywords and phrases mined from the PubMed search. The initial search retrieved 364 articles from the four databases (PubMed (117), CINAHL (59), Web of Science (165), and PsycINFO (23). Appendix A indicates the search strategy. All results were exported into the citation manager, Zotero, where 163 duplicates were removed. The 201 unique citations were then exported into Covidence© to facilitate the study selection and screening process.

Study selection of evidence

Article titles and abstracts were initially screened by members of the project team using the following inclusion criteria: original research, cancer, and shared decision making. Exclusion criteria were carefully considered and included studies focused on pediatric patients and studies conducted outside of the USA. Pediatric studies were excluded as it was felt this body of literature focuses on a particularly complex subset of SDM dynamics involving parents and children; non-US-based studies were excluded as accounting for differing global cultural and social norms related to SDM was beyond the scope of this review. Review articles were also excluded to avoid duplication of articles that met the criteria. Following the initial article title/abstract screen, 146 articles were deemed irrelevant and excluded; 55 articles were selected for full-text review. For both the initial title and abstract screening, and the full-text review, all articles were independently reviewed by at least two members of the project team (PD; RJ; VL), and any discrepancies were resolved by a group discussion to reach a final consensus.

Synthesis of results

The authors summarized the studies’ aims, type of study design, cancer type, sample size, primary outcome measure used, and the shared decision-making findings from the studies. At least two members of the project team (PD; RJ; VL) independently analyzed the results from the review to develop and validate the emerged themes. Those themes were then confirmed by all three of the authors (PD; RJ; VL).

Results

Characteristics of included studies

Fifty-five articles underwent full review, in which forty-four of those articles were excluded based on the following reasons: 16 were not based in the USA, 13 were not original research, 6 were not focused on SDM, 2 were systematic reviews, and 7 were not cancer focused. Figure 1 (PRISMA-ScR flow diagram) provides an overview detailing reasons for article exclusion. Eleven articles met the full criteria for this scoping review, and the following data were extracted: author, year, and journal, a brief overview, study design, outcomes, and SDM findings. A summary chart of the assessment and studies is seen in Table 1.

Study design and setting

Eleven studies of patients with cancer in the USA published between 2016 and 2020 were included. Nine of the 11 studies were quantitative, including one longitudinal interventional randomized control trial [33]; one pre- and post-test evaluation of a pilot communication preferences tool [36]; and four cross-sectional survey studies, which included multiple secondary data analyses [28, 30, 34, 35]. The two remaining studies were qualitative, which included semi-structured interviews [37] with opioid prescribers and patients regarding informed consent and SDM among patients with cancer on long-term opioid therapy and analysis of recorded transcripts of inpatient goals-of-care meetings to explore for SDM themes [38]. The majority of the 11 studies took place at urban academic medical or cancer centers [28, 30,31,32,33,34, 36, 38]. Six were multi-site studies [28, 30, 33,34,35, 37]. One study included nationwide hospice home visits in both rural and urban settings [35]. Two studies included VA medical centers [34, 37]. One urban-based study allowed a small number of participants to finish their participation online via social media [36]. Three studies were focused on community-based cancer center patients,[28, 29, 34] but no study specified if these centers were rural.

Participants and decision types

Elliot et al. [31] focused only on the healthcare team and did not include patient participants. Six studies focused on patients only,[28,29,30, 33, 34, 36] and four studied both patients and the healthcare team [32, 35, 37, 38]. Of those that included patients, six highlighted patients making decisions during active treatment [28, 30, 32,33,34, 38], two studies centered on post-treatment cancer survivors [29, 36], and one study focused on a mix of patients who were either receiving active treatment or who had entered survivorship [37]. Two of the included studies focused on patients facing decisions at the end of life [31, 38]. Regardless of patient treatment status, the majority (n = 9) of the included studies looked at SDM only very generally and did not describe what types of decisions were being undertaken by patients and healthcare teams [28, 30, 31, 33,34,35,36]. Sharma et al. [38] specified that patients were facing decisions regarding treatment continuation, beginning hospice, and code status. Wheeler et al. [29] and Giannitripani et al. [37] examined decisions around hormone replacement therapy and long-term opioid use, respectively. Winner et al. [32] compared expectation for a surgical cure between patients and surgeons, and SDM was considered a contributing factor in each group’s perceptions of the possible outcomes (e.g., extend life, relieve symptoms).

Descriptions of shared decision making

Only four of the 11 studies included any definition of SDM [32, 35, 37, 38]. Of those that did, only one utilized an existing SDM model and tied it to the included definition [35]. One study created a new study-specific model for SDM based on their findings [38]. The remaining two studies defined SDM but did not attempt to tie that definition to a model or to operationalize any potential variables of SDM [32, 38]. The seven studies which did not define SDM examined it as a contributing factor in health-related quality of life [28], perceived quality of relationships with the health care team [28, 31, 37], quality and ease of communication between clinician and patient [31, 32, 36], inequitable treatment offerings [29, 30], patient coping strategies [34], and preferences surrounding decisional control. [30, 32,33,34]

Elements of shared decision making

Only one study operationalized a well-known model of SDM by Makhoul and Clayman [35]. One other study [38] distinguished four distinct DM stages (information exchange, deliberation, making a patient-centered recommendation, wrap-up) and created their own model of SDM; they utilized this model to identify “missed opportunities” by clinicians to support SDM in goals-of-care conversations [38]. Three studies included DAs; Trinh et al. [30] and Berry et al. [33] each utilized the Personal Patient Profile-Prostate (P3P) decision-making aid to help patients identify personal preferences and choose a path for treatment of prostate cancer. Frey et al. [36] piloted a tool designed for waiting room use in which patients could identify goals and talking points for their upcoming visit for ovarian cancer follow-up care.

SDM findings

Race and inequities

Several studies concluded that clinicians often missed opportunities to involve patients in the SDM process,[28,29,30,31,32, 34, 38] particularly studies which focused on inequitable care experienced by Black compared to White patients. For example, Elliot et al. [31] created a simulation of encounters between critically ill patient-surrogate teams and physicians and observed for differences in verbal and nonverbal communication between Black patient/surrogate and White patient/surrogate pairs. They found that although there was no difference in verbal communication between doctors and Black or White participants, there was a significant difference in the quality of the nonverbal communication between doctors and Black patient participants. Doctors offered Black patients and surrogates less rapport-building opportunities and fewer positive nonverbal cues (such as turning toward the patient, amount of time spent with the patient, and standing near the patient). Elliot et al. [31] found that Black patients and surrogates received less caring, open, and receptive behaviors than White patients, which can negatively influence the SDM process. Additionally, they found that physicians only asked whether anyone else needed to be involved in decision making in 13% of cases and only offered reassurance regarding the decision that was made 5.6% of the time, regardless of race.

In the study by Wheeler et al. [29], Black women more often presented with advanced staged cancer and financial instability, experienced more side effects related to use (or lack of use) of endocrine therapy (ET), and reported worse communication with clinicians than White women. Patients who felt the decision to start ET had been primarily patient- or clinician-led were less likely to adhere to the ET treatment plan than those patients who described the decision as being shared. Black women more often believed that ET would not affect future cancer outcomes, and patients who held those beliefs were less likely to adhere to ET treatment plans. For patients who completed the decision aid in the Trinh et al. study,[30] age (Black men decisions were less influenced by age than White and Hispanic men), famous people (Hispanic and Black men were more influenced by famous people’s decisions than White men), religion (Black and Hispanic men influenced by religion more than White men), and future bladder problems (White men more influenced than Black men). Confidence in a doctor was less likely to be favored as a reason to choose a specific treatment in Black men than in White men in this study. Black patients in the Samuel et al.[28] study were more likely to have severe pain than White patients, and to report not following their doctor’s advice. Patients who spent less time than they wanted to with their doctor during the decision-making process reported lower HRQOL than those who felt their physician spent the right amount of time with them.

Patient and clinician perceived communication

The perception of respect from physicians was a significant factor for patients in several studies. Patients in the Samuel et al.[28] study who reported feeling a lower level of respect from their doctor had lower than average physical and mental health-related quality of life (HRQOL) scores and were more likely to report higher levels of pain than their counterparts who perceived more physician respect, even after adjusting for other clinical and sociodemographic factors. The authors found no other statistically significant factor involved with moderate-to-severe pain than a patient-perceived degree of physician respect.

Sharma et al. [38] examined audio recordings of goals-of-care meetings for patients hospitalized with cancer. They found that although physicians presented patients with options as they saw them, they generally missed opportunities to engage patients nearing the end of their lives in discussions surrounding goals of care. For patients considering more treatment, deliberative conversations and patient-centered therapy recommendations were often included in the discussion, but patients’ own evaluations of treatment harms and benefits were often not addressed. In several instances, patient requests for recommendations were not honored; similarly, patients and family members were left to make the decision to enter hospice on their own. However, when addressing inpatient code status, physicians did make patient-centered recommendations, but did not often clarify whether their recommendations meshed with patient preference. Similarly, Oliver et al.[35] found that, especially in times of stress, patients naturally look to physicians or others in the medical team for clear and specific direction; as one of their participants stated, “I need you to tell me what to do.” (p. 928).

Elements of SDM

In Oliver et al.’s [35] secondary data analysis, audio-recorded hospice nurse visits to cancer patients were analyzed for elements of Makoul and Clayman’s [39] Nine Essential Elements for SDM [define the problem, present options, discuss pros/cons, patient values/preferences, patient ability, provider knowledge/recommendations, check understanding, make or explicitly defer decision, and arrange follow-up]. They found that the most identified element was “defining the problem.” The least commonly utilized element was “assessment of patient and family understanding.” Around 25% of the nursing visits utilized 6–7 elements, 28% of nursing visits utilized 4–5 elements, while 8% of the visits used all but one of the elements and only 3% used all nine.

Patient and clinician quality of communication

Communication quality can also impact patient capacity for hope and satisfaction, as Winner et al. [32] reported in their comparison of patient and surgeon expectations for a surgical cure. Patients who reported excellent communication with their surgeon had statistically higher hopes that surgery would cure their cancer, even if surgeons did not feel they had communicated that. The authors postulated that optimism may be associated with increased patient coping and that optimistic messaging from physicians may be associated by patients with increased levels of respect and better care from their doctor.

Patient communication preferences

Communication preferences and needs extend far beyond the SDM process. Colley et al.[34] examined a variety of factors such as anxiety, depression, coping style, personality traits, resilience, and preferred decisional control style and found that participants’ preferences for involvement in SDM are associated with both coping style and personality and that decision-making preferences may be a subtype of coping style. Coping and role preference were strongly related to a decision-making role, even after controlling for patient demographics. Patients who preferred a more passive approach to decision making were also more likely to be “avoidant” or “fatalistic” copers; “forcing” a more active role in decision making for these patients, if that is even possible, may contribute to increased stress or other negative outcomes.

Tools to support shared decision making

Four of the studies utilized tools or decision-making aids to assist patients in choosing treatment options to clarify their own communication needs before visits [30, 33, 36, 37]. Both the Trinh et al. and the intervention arm of the Berry et al. studies utilized the P3P decision. In their RCT, Berry et al. [33] found that use of the P3P decision aid significantly reduced decisional conflict (defined as personal uncertainty about prostate cancer treatment) in the intervention group. Decisional conflict was significantly associated with higher age, center at which the patient was seen, race other than White, low income, increased baseline anxiety, and baseline feelings of having received inadequate information and lacking support. Frey et al. [36] developed a pilot tool in which survivors of ovarian cancer filled out a short form before their visit to help them clarify their goals and questions before seeing their physician. Although it was a small study (n = 36), over half of the participants stated that the tool would help them feel more comfortable participating in SDM practices the next time they needed to make a cancer treatment decision.

In a study at Veteran’s Administration (VA) hospitals, Giannitripani et al.[37] interviewed clinicians and patients for their perspectives on expanding the VA “Signed Informed Consent” (SIC) forms program required for use in long-term opioid therapy (LTOT), which cancer patients were exempted. The authors describe SIC as similar to SDM, and as “a tool to educate patients about the risks, benefits, and alternatives to LTOT and engage them in a discussion about a proposed LTOT management plan… [it] enables a clinician and a patient to participate in jointly in making a health decision…having considered the patient’s values, preferences, and circumstances.” (p 50). Both patients and physicians in this study were interested in finding ways to involve patients in discussions around treatment and goals but were wary of anything (such as requiring signatures on a SIC form) that might erode rapport between physician and patient or might interfere with the patient’s ability to receive adequate relief from cancer pain.

Discussion

This scoping review of SDM oncology literature in the USA revealed that there remain discrepancies in the definition and conceptualization of SDM and what it means to the patient with cancer, their caregivers, and clinicians. The importance of understanding the meaning of SDM is vital. However, there is a lack of clarity on both how to define and how to effectively evaluate SDM which can impact how investigators and clinicians approach, measure, and study SDM in patients with cancer [12]. As mentioned previously, a definition of SDM was rarely reported (only four studies) and only one study had incorporated a model of SDM within this review, which could cause issues when attempting to distinguish between other related terms, such as partnerships, patient-centered care, and patient involvement [40]. In addition, in the US-based studies reviewed, each used a different measure to evaluate a component of SDM that may or may not have been defined, which can cause some confusion to readers when evaluating SDM. These inconsistencies create significant challenges toward model operationalization and generalizability of findings. Makhoul and Clayman pointed out in 2006 that there was no standard definition of SDM, and that investigators are not grounding research in clear and established concepts[35], which appears to be congruent in current work. There is a need to develop a clearer definition of SDM that clinicians and investigators can use to help guide research and practice.

In addition, despite the fact that SDM is a shared process resulting in major impacts (i.e., quality of life, knowledge, treatment satisfaction) [41] on patients’ lives, the majority of current SDM literature within the USA focuses nearly exclusively on clinicians or includes patient perspectives on SDM only minimally [11]. The SDM literature rarely includes other stakeholders, such as family caregivers or other people close to the patient [11]. Inclusion of patients’ caregivers in the SDM process allows the patient to have decisional support during difficult clinical decisions. During clinical visits, patients may demonstrate distress, anxiety, and fear about treatment and may not understand everything from the clinician’s discussion, thus impacting decision-making [42, 43]. A patient’s caregiver can help take notes and offer support to help explain and discuss options with the patient after the clinical visit. This may provide additional support and an opportunity to discuss options with the patient in a less stressful environment. Not only does the lack of clarity in SDM affect healthcare clinicians and investigators, but ultimately the patient when there may be potential missed opportunities to enhance patients’ health [44].

Communication is a key factor in the decision-making process; however, this is not always performed equally among all clinician and patient interactions [45]. Inadequate verbal and nonverbal communication between clinician and patient in relation to their race and ethnicity affects what options are offered and ultimately what decisions are made. Inequality in communication, intentional or not intentional, can compromise the type and quality of care that patients receive [46, 47]. Considering that historically marginalized groups within the USA are affected by structural racism, socioeconomics, and other factors that are associated with increased risks and prevalence of certain cancers and lack of adequate cancer care, there is a need for understanding and identifying complex barriers to communication between patient, caregiver, and clinicians [48]. Although this scoping review revealed four articles that utilized decision aids for treatment choice, the decision aids did not address factors that influence clinicians’ attitudes, biases, or communication enhancements during SDM. There is a need for the development and testing of interventions that target bidirectional communication in SDM to enhance patients’ healthcare experiences. [49]

In refining what SDM means in oncology, there is a need for research that is more patient and caregiver oriented. Callon et al.[50] note that SDM models emerged in a “top-down” theoretical fashion, describing what should happen and relatively ignoring what often does happen and suggest that, as a result, SDM in clinical practice rarely ever includes all suggested elements (i.e., discuss patients’ preferred level of involvement, explicitly state all options). Several investigators [51, 52] have proposed moving away from single-decision point implementation of SDM and toward a model that is based on a cultivated, ongoing relationship between a clinician and a patient. From this perspective, decisions would not be viewed as single points between strangers, but as part of a process that respects each participant’s perspective, not just related to one decision but as a series of ongoing decisions that impact a patient’s life across the illness trajectory.

These findings within the US oncology literature support the need for additional research to address the meaning of SDM, the clinician’s respect toward patients’ end-of-life discussions, preference elicitation, and patients’ preferred mode of involvement related to SDM. This scoping review offers concrete guidance for future research and designing effective SDM interventions.

Limitations

This review is limited by our selection of English language, US-based studies that focus on the adult population. Studies conducted in other countries and/or focused on pediatrics may offer varying clinical perspectives and reach different conclusions regarding SDM due to different cultural norms related to clinician-patient communication and approaches to cancer management in diverse healthcare systems. We also chose a five-year timeframe for this scoping review with the rationale that cancer therapies – and the dynamic decisions that undergird them – continue to evolve at a rapid pace. However, this timeframe criteria obviously excluded older articles from our analysis that may be important for historical perspectives related to SDM. We also chose to limit our scoping review to the cancer population. This was an intentional decision due to our assessment that a recent and comprehensive exploration of SDM and cancer care was needed to fill a gap in the literature. Lastly, although our search strategy was guided by an expert health sciences librarian, it is possible some studies were missed.

Conclusions

Despite the importance of SDM along the entire cancer care continuum, this scoping review identified two critical research gaps within the US-based SDM-related oncology literature: (1) lack of clear consensus regarding the definition and operationalization of SDM and (2) limited evidence of the involvement of key stakeholders, such as caregiver perspectives in the SDM process. These gaps can be addressed by future research which focuses on developing interactive and bidirectional SDM interventions that take into account (1) racial inequality, (2) preference elicitation, and (3) the clinician-patient relationship and preferred degree of involvement.

Data availability

Relevant documentation is available upon request.

References

Gattellari M, Butow PN, Tattersall MH (2001) Sharing decisions in cancer care. Soc Sci Med 1982 52(12):1865–1878. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00303-8

Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T (1997) Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Soc Sci Med 1982 44(5):681–692. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00221-3

Tariman JD, Berry DL, Cochrane B, Doorenbos A, Schepp KG (2012) Physician, patient, and contextual factors affecting treatment decisions in older adults with cancer and models of decision making: a literature review. Oncol Nurs Forum 39(1):E70-83. https://doi.org/10.1188/12.ONF.E70-E83

Politi MC, Studts JL, Hayslip JW (2012) Shared decision making in oncology practice: what do oncologists need to know? Oncologist 17(1):91–100. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0261

Wiener RS, Koppelman E, Bolton R et al (2018) Patient and Clinician perspectives on shared decision-making in early adopting lung cancer screening programs: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med 33(7):1035–1042. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4350-9

Ozdemir S, Malhotra C, Teo I et al (2021) Patient-reported roles in decision-making among Asian patients with advanced cancer: a multicountry study. MDM Policy Pract 6(2):23814683211061400. https://doi.org/10.1177/23814683211061398

Josfeld L, Keinki C, Pammer C, Zomorodbakhsch B, Hübner J (2021) Cancer patients’ perspective on shared decision-making and decision aids in oncology. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 147(6):1725–1732. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-021-03579-6

Ankolekar A, Vanneste BGL, Bloemen-van Gurp E et al (2019) Development and validation of a patient decision aid for prostate cancer therapy: from paternalistic towards participative shared decision making. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 19(1):130. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-019-0862-4

Scholl I, LaRussa A, Hahlweg P, Kobrin S, Elwyn G (2018) Organizational- and system-level characteristics that influence implementation of shared decision-making and strategies to address them — a scoping review. Implement Sci 13(1):40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-018-0731-z

Lu Y, Elwyn G, Moulton BW, Volk RJ, Frosch DL, Spatz ES (2022) Shared decision-making in the U.S.: evidence exists, but implementation science must now inform policy for real change to occur. SchwerpunktSpecial,, Issue Int Shar Decis Mak Conf 171:144–149

Bomhof-Roordink H, Gärtner FR, Stiggelbout AM, Pieterse AH (2019) Key components of shared decision making models: a systematic review. BMJ Open 9(12):e031763. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031763

Entwistle VA, Cribb A, Watt IS (2012) Shared decision-making: enhancing the clinical relevance. J R Soc Med 105(10):416–421. https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.2012.120039

Levit L, Balogh E, Nass S, Ganz PA (eds) (2013) Delivering high-quality cancer care: charting a new course for a system in crisis. National Academies Press, US

Brenner AT, Malo TL, Margolis M et al (2018) Evaluating shared decision making for lung cancer screening. JAMA Intern Med 178(10):1311–1316. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3054

Mazzone PJ, Tenenbaum A, Seeley M et al (2017) Impact of a lung cancer screening counseling and shared decision-making visit. Chest 151(3):572–578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2016.10.027

Heathcote LC, Goldberg DS, Eccleston C et al (2018) Advancing shared decision making for symptom monitoring in people living beyond cancer. Lancet Oncol 19(10):e556–e563. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30499-6

Kuosmanen L, Hupli M, Ahtiluoto S, Haavisto E (2021) Patient participation in shared decision-making in palliative care – an integrative review. J Clin Nurs 30(23–24):3415–3428. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15866

Gärtner FR, Bomhof-Roordink H, Smith IP, Scholl I, Stiggelbout AM, Pieterse AH (2018) The quality of instruments to assess the process of shared decision making: a systematic review. van Wouwe JP, ed. PLOS ONE 13(2):e0191747. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0191747

Kashaf MS, McGill E (2015) Does shared decision making in cancer treatment improve quality of life? A systematic literature review. Med Decis Mak Int J Soc Med Decis Mak 35(8):1037–1048. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989X15598529

Yu CH, Ke C, Jovicic A, Hall S, Straus SE (2019) Beyond pros and cons – developing a patient decision aid to cultivate dialog to build relationships: insights from a qualitative study and decision aid development. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 19(1):186. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-019-0898-5

O’Connor AM, Stacey D, Entwistle V et al (2003) Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2:1–132. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001431

Stacey D, Bennett CL, Barry MJ et al (2011) Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 10(10):1–131. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub3

Covvey JR, Kamal KM, Gorse EE et al (2019) Barriers and facilitators to shared decision-making in oncology: a systematic review of the literature. Support Care Cancer 27(5):1613–1637. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04675-7

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W et al (2018) PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 169(7):467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

Arksey H, O’Malley L (2005) Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 8(1):19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Patt D, Gordan L, Diaz M et al (2020) Impact of COVID-19 on cancer care: how the pandemic is delaying cancer diagnosis and treatment for American seniors. JCO Clin Cancer Inform 4:1059–1071. https://doi.org/10.1200/CCI.20.00134

John N, Wang GM, Cioffi G et al (2021) The negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on oncology care at an academic cancer referral center. Oncol Williston Park N. 35(8):462–470. https://doi.org/10.46883/ONC.2021.3508.0462

Samuel CA, Mbah O, Schaal J et al (2020) The role of patient-physician relationship on health-related quality of life and pain in cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 28(6):2615–2626. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-05070-y

Wheeler SB, Spencer J, Pinheiro LC et al (2019) Endocrine therapy nonadherence and discontinuation in Black and White women. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst 111(5):498–508. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djy136

Trinh QD, Hong F, Halpenny B, Epstein M, Berry DL (2020) Racial/ethnicity differences in endorsing influential factors for prostate cancer treatment choice: an analysis of data from the personal patient profile-prostate (P3P) I and II trials. Urol Oncol Semin Orig Investig 38(3):78.e7-78.e13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urolonc.2019.10.015

Elliott AM, Alexander SC, Mescher CA, Mohan D, Barnato AE (2016) Differences in physicians’ verbal and nonverbal communication with Black and White patients at the end of life. J Pain Symptom Manage 51(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.07.008

Winner M, Wilson A, Yahanda A, Kim Y, Pawlik TM (2016) A cross-sectional study of patient and provider perception of “cure” as a goal of cancer surgery: patient and provider perception of cure. J Surg Oncol 114(6):677–683. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.24401

Berry DL, Hong F, Blonquist TM et al (2018) Decision support with the personal patient profile-prostate: a multicenter randomized trial. J Urol 199(1):89–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2017.07.076

Colley A, Halpern J, Paul S et al (2017) Factors associated with oncology patients’ involvement in shared decision making during chemotherapy: factors associated with patient involvement in shared decision making. Psychooncology 26(11):1972–1979. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4284

Oliver DP, Washington K, Demiris G et al (2018) Shared decision making in home hospice nursing visits: a qualitative study. J Pain Symptom Manage 55(3):922–929. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.10.022

Frey MK, Ellis A, Shyne S, Kahn R, Chapman-Davis E, Blank SV (2020) Bridging the gap: a priorities assessment tool to support shared decision making, maximize appointment time, and increase patient satisfaction in women with ovarian cancer. JCO Oncol Pract 16(2):e148–e154. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.19.00455

Giannitrapani KF, Fereydooni S, Azarfar A et al (2020) Signature informed consent for long-term opioid therapy in patients with cancer: perspectives of patients and providers. J Pain Symptom Manage 59(1):49–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.08.020

Sharma RK, Cameron KA, Zech JM, Jones SF, Curtis JR, Engelberg RA (2019) Goals-of-care decisions by hospitalized patients with advanced cancer: missed clinician opportunities for facilitating shared decision-making. J Pain Symptom Manage 58(2):216–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.05.002

Makoul G, Clayman ML (2006) An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Educ Couns 60(3):301–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2005.06.010

Moumjid N, Gafni A, Brémond A, Carrère MO (2007) Shared decision making in the medical encounter: are we all talking about the same thing? Med Decis Making 27(5):539–546. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989X07306779

Stacey D, Bennett C, Barry M. et al. (2017) Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database System Rev. Issue 4. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub3

Gritti P (2015) The family meetings in oncology: some practical guidelines. Front Psychol 5:1552. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01552

PDQ® Supportive and Palliative Care Editorial Board. PDQ communication in cancer care. Published online June 3, 2021. Accessed May 20, 2022. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/coping/adjusting-to-cancer/communication-pdq

Gionfriddo MR, Leppin AL, Brito JP, Leblanc A, Shah ND, Montori VM (2013) Shared decision-making and comparative effectiveness research for patients with chronic conditions: an urgent synergy for better health. J Comp Eff Res 2(6):595–603. https://doi.org/10.2217/cer.13.69

Shen MJ, Peterson EB, Costas-Muñiz R et al (2018) The effects of race and racial concordance on patient-physician communication: a systematic review of the literature. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 5(1):117–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-017-0350-4

Blair I, Steiner J, Fairclough D et al (2013) Clinicians’ implicit ethnic/racial bias and perceptions of care among Black and Latino patients. Ann Fam Med 11(1):43–52

Vermeir P, Vandijck D, Degroote S et al (2015) Communication in healthcare: a narrative review of the literature and practical recommendations. Int J Clin Pract 69(11):1257–1267

Zavala VA, Bracci PM, Carethers JM et al (2021) Cancer health disparities in racial/ethnic minorities in the United States. Br J Cancer 124(2):315–332. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-020-01038-6

Jones R, Hirschey R, Campbell G et al (2021) Update to 2019–2022 ONS Research agenda: rapid review to address structural racism and health inequities. Oncol Nurs Forum 48(6):589–600. https://doi.org/10.1188/21.ONF.589-600

Callon W, Beach MC, Links AR, Wasserman C, Boss EF (2018) An expanded framework to define and measure shared decision-making in dialogue: a ‘top-down’ and ‘bottom-up’ approach. Patient Educ Couns 101(8):1368–1377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2018.03.014

Clancy C. How patient-centered healthcare can improve quality. Patient Saf Qual Healthc. Published online April 2008. https://www.psqh.com/marapr08/ahrq.html

Hibbard JH, Greene J (2013) What the evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health Aff Proj Hope 32(2):207–214. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1061

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study’s conception and design.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Bennett, R., DeGuzman, P.B., LeBaron, V. et al. Exploration of shared decision making in oncology within the United States: a scoping review. Support Care Cancer 31, 94 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07556-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07556-8