Abstract

Background

Shared decision-making (SDM) in the management of metastatic breast cancer care is associated with positive patient outcomes. In daily clinical practice, however, SDM is not fully integrated yet. Initiatives to improve the implementation of SDM would be helpful. The aim of this review was to assess the availability and effectiveness of tools supporting SDM in metastatic breast cancer care.

Methods

Literature databases were systematically searched for articles published since 2006 focusing on the development or evaluation of tools to improve information-provision and to support decision-making in metastatic breast cancer care. Internet searches and experts identified additional tools. Data from included tools were extracted and the evaluation of tools was appraised using the GRADE grading system.

Results

The literature search yielded five instruments. In addition, two tools were identified via internet searches and consultation of experts. Four tools were specifically developed for supporting SDM in metastatic breast cancer, the other three tools focused on metastatic cancer in general. Tools were mainly applicable across the care process, and usable for decisions on supportive care with or without chemotherapy. All tools were designed for patients to be used before a consultation with the physician. Effects on patient outcomes were generally weakly positive although most tools were not studied in well-designed studies.

Conclusions

Despite its recognized importance, only two tools were positively evaluated on effectiveness and are available to support patients with metastatic breast cancer in SDM. These tools show promising results in pilot studies and focus on different aspects of care. However, their effectiveness should be confirmed in well-designed studies before implementation in clinical practice. Innovation and development of SDM tools targeting clinicians as well as patients during a clinical encounter is recommended.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer type among women worldwide and the fifth cause of cancer related deaths [1]. In metastatic breast cancer care many complex decisions need to be made, of which most are preference-sensitive [2, 3]. Important treatment decisions include for example whether or not to start chemotherapy or targeted therapy [4].

Shared decision making (SDM) is an approach in which health care providers and patients share the best evidence when facing decisions, and patients are encouraged to be actively involved in decision making [5, 6]. SDM has been identified as an important element for good advanced cancer care [7]. Most cancer patients prefer to participate in decision making [8, 9]. Among patients with advanced cancer, women with breast cancer in particular wish to be actively involved in decision making [10]. SDM is associated with positive patient outcomes, including knowledge regarding available options, perceived quality of care [11, 12], and quality of life [13].

The use of tools might support active participation of patients in decision-making. Examples of such instruments are 1) decision aids (DAs) which are designed to be used by patients before doctor visits to prepare for decision making [14,15,16], and 2) tools to be used by both health care providers and patients during clinical encounters [17, 18]. DAs are developed to support patients in decision making by providing an overview of the available (treatment) options and their associated outcomes [15, 19]. There are many types of DAs, such as video or audiotapes, patient letters, computer programs, leaflets, and interactive media [12].

The tools designed to be used during consultation with a health care provider have been developed to facilitate a conversation between health care providers and patients about the relevant (treatment) options. In general, these tools are brief and present a summary of available options. Examples are decision boards, bar charts, option grids and consult decision aids [17, 18, 20,21,22].

The aims of this study were 1) to make an inventory of instruments and tools, including DAs and tools used during clinical encounters, that are currently available for supporting SDM in metastatic breast cancer care and 2) to evaluate the effectiveness of these tools based on published studies.

Methods

Three strategies were used to identify tools for supporting SDM in metastatic breast cancer. First, a systematic search of relevant databases was undertaken, secondly an internet search was conducted and lastly experts who appeared in the searches were contacted.

Systematic search

Search strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted in Cinahl, Medline, PsychInfo and Pubmed to identify relevant articles published between 1 January 2006 and 18 January 2017. This time frame was chosen as we were looking for tools that are still clinical relevant and up-to-date. If there were instruments developed before 2006 that are still relevant, we would have find them in either later publications, via our internet search, or via the experts that we have approached. The search strategy was developed in collaboration with an experienced librarian and checked by an expert in the field. It combined terms covering the areas of breast cancer (breast cancer; breast carcinoma; breast neoplasms), advanced cancer (advanced cancer, metastatic cancer, palliative care), decision making (decision making, decision support, decision aid, shared decision) (Appendix 1). Hand-searching of reference lists of included articles was conducted to identify additional studies.

Study selection

The search was performed by one reviewer (IS), and after removal of duplicates, irrelevant articles were eliminated on the basis of title and abstract. Ten percent was independently evaluated by two reviewers (IS and JK). There was no disagreement between the reviewers on inclusion. Therefore, the remaining abstracts were evaluated by one reviewer (IS). Screening of full text of relevant articles was independently performed by two reviewers (IS and JK). Disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third reviewer (FS).

Inclusion criteria

Research articles and (systematic) reviews on studies conducted in advanced breast cancer patients, written in any language and published in a peer-reviewed journal were included for review. Studies needed to focus on the development and/or evaluation of an initiative or tool that focused on i) information provision about decisions, ii) decision making process, or iii) eliciting treatment preferences in metastatic breast cancer care. Outcomes included in the studies had to be any i) patient-reported outcome, or ii) health outcome.

Data extraction

Characteristics of tools (name, country, description, target population, type of tool, decision on which tool focusses), study characteristics (first author, year of publication, study size, patients characteristics, study design, outcome measures) and patient-reported and health outcomes were independently extracted by two reviewers (IS and JK).

Study quality

Quality of the studies evaluating the tools was independently assessed by two reviewers (IS and JK) using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology [23]. This methodology classifies evidence into four levels of quality (high to very low). First the studies were classified based on their design, with high quality for randomized control trials and low quality for observational studies. These initial grades can be downgraded or upgraded after assessment of their weaknesses and strengths. The five downgrading criteria are risk of bias, indirectness of evidence, inconsistency of results imprecision of results, and publication bias. The three upgrading criteria are large magnitude of effect, dose-response, and opposing residual confounding or bias. Based on the up- and downgrading criteria, the final evidence grade was determined [23].

Internet search and consultation of experts

An internet search was performed and experts were approached to complement the systematic literature search using the same inclusion criteria. Google searches covering the areas metastatic breast cancer (advanced breast cancer, metastatic breast cancer, palliative breast cancer care) and decision making (decision making, decision support, decision aid, shared decision) were carried out and websites presenting an overview of decision aids were studied (http://www.med-decs.org/, https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/). National and international experts who appeared in the systematic literature and internet searches were approached via email and asked whether they were aware of tools, instruments or initiatives supporting SDM in metastatic breast cancer care. From the tools identified by internet searches and experts the same characteristics were extracted as from those identified by the systematic literature search.

Results

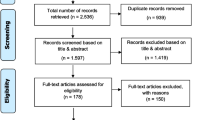

The initial literature search resulted in 687 potentially relevant articles. After removal of duplicates and elimination of non-eligible papers based on title and abstract, 13 full-text articles were considered, of which seven were included for review (Fig. 1). The seven articles described five different tools. In addition, the internet search revealed two relevant tools. All 17 experts approached responded and identified one additional relevant tool (Table 1).

In total, seven tools were identified (Table 1). Three were developed in the USA, three in the Netherlands and one in Canada and Australia. Four tools were specifically designed for metastatic breast cancer, the others for metastatic cancer patients in general. Three tools focused on the decision on whether or not to start chemotherapy [24,25,26,27]. The other four focused on all possible decisions during the entire metastatic breast cancer care trajectory. All tools were developed for patients to be used before consultation with their health care provider. Only one tool [28] provided a summary report to the health care provider which could be discussed during a consultation.

The content of five out of seven tools was evaluated in published studies (Table 2). Of four of these, the effectiveness was studied as well. CONNECT, the communication aid from Meropol et al. was tested in a randomized clinical trial [28]. Outcome measures included consultation content, treatment outcome expectations, decisional conflict, patient satisfaction with the content and format of the communication, and satisfaction with the survey and/or communication skills training. CONNECT made it easier for patients to make treatment decisions (P = 0.003) and patients were more satisfied with their decision (P < 0.001), with physician communication (P = 0.026), with discussion regarding support services (P = 0.029) and quality of life concerns (P = 0.042), but not with discussion of diagnosis/prognosis, treatment options, or support/community services. The DA of Oostendorp et al., [25, 26, 29] was evaluated in a randomized clinical trial. Primary outcome measures included several measurements on patient’s well-being on which the DA had no statistically significant effect. The DA was associated with stronger treatments preferences of patients (P = 0.030) and with increased subjective knowledge (P = 0.022), but not with any of the other secondary outcomes measures. The two other tools [27, 30] were tested in pilot studies without control groups. The DA of Smith et al. [27] assessed whether patients choose to use the DA, investigated the knowledge of patients about the disease and treatment and examined whether the information of the DA was helpful and if the patient wanted to share the information with the physician. All except one patient used the DA and knowledge about the cure of advanced cancer improved after using the DA (P = 0.15). Most patients found the information helpful and almost all patients wanted to share information with their physician after use of these DAs, which might result in SDM. The study on the DA developed by Sepucha et al. [30] evaluated acceptability of the DA and its impact on decisions. The DA was rated acceptable, did not increase distress (P = 0.34) and the treatment goal was most often to lengthen life. Most patients (88%) wanted to be involved in shared decision making, however, only 41% found that decision making was shared and 38% achieved their desired level of participation in decision making. The content of the tool and attitudes towards the tool developed by Chiew et al. was evaluated by both patients and medical oncologists [24]. The patients concluded that the DA was acceptable and helpful and the majority recommend the use of this DA to others. Also the oncologists were positive about the DA and found the DA appropriate for all or most patients.

The quality of five evaluation studies could be assessed. According to the GRADE approach, the quality of the studies ranged between moderate and very low (Table 2). All studies had noteworthy shortcomings, mainly because of the study design. Two had a randomized design and the others were observational studies [24, 27, 30]. The quality of the three observational studies was downgraded to ‘very low’ due to small samples sizes, unclear descriptions of inclusion criteria and lack of information on loss to follow-up. The quality of the studies with a randomised design was downgraded as well [28, 29]. Both studies had a high drop-out rate. And one defined no primary outcome and presented selective results as two of the intervention arms were combined to obtain significant results.

Discussion

This review identified seven tools to support SDM in metastatic breast cancer care. All were designed to be used independently by patients before consulting a physician. None was developed to be used by both a health care provider and patient during a clinical encounter, although one tool provided a summary report for the physician which could be discussed during a consultation. In general, the identified tools had positive effects on patient satisfaction with their treatment decision and on patients’ desire to share information with their physician. However, it is unclear whether they encourage SDM during a clinical encounter as this was not studied. The effectiveness of the included tools was barely studied. Evidence from the included studies was in general low due to multiple sources of bias, which may have skewed the results.

The revealed tools to support patients in SDM have some limitations. The effectiveness of only four of them was evaluated [27,28,29,30]. Of these, the one with the highest level of evidence was not effective [29]. The other tool with a somewhat higher level of evidence of effectiveness is not available anymore [28] as the tool was not kept up-to-date. The two remaining tools might be useful in clinical practice as their results are promising in pilot studies. These tools could be used next to each other as the DA of Smith et al. [27] focuses on chemotherapy, whereas the DA of Sepucha et al. [30] shows the experiences of four women living with metastatic breast cancer. A limitation of these tools is that they were only tested in a pilot study without a control group. Further testing of these tools in better designed studies is required before they are implemented. The consultation guide presenting information on therapies and supportive treatment in metastatic breast cancer, was not evaluated, but might also be useful for patients with metastatic breast cancer.

Despite the calls for integrating SDM in clinical practice, implementation of SDM into daily care is lacking [31,32,33,34]. The lack of available SDM supporting tools and time concerns might be barriers for implementation [6]. Our review shows the availability of a few tools to be used by patients before visiting the physician and the lack of tools to be used during a clinical encounter in metastatic breast cancer care. In general, tools to be used by patients before visiting the health care provider lead to better understanding of choices, however, yet are not enough to guarantee SDM [14, 35]. In order to facilitate SDM during a clinical encounter, SDM tools for both health care providers and patients have been designed [35,36,37]. For curative breast cancer and other tumour types, such tools are available [17, 18]. These tools make options more visible, enhances patients confidence and involvement, and clinicians find it easier to implement SDM in practice [18]. For decision making in metastatic breast cancer care, there is a pressing need for similar tools as many complex decisions have to be made and alignment of care with patient preferences is necessary.

When developing, testing and implementing tools for SDM during a clinical encounter, several recommendations can be made. First, tools should be based on the best available scientific evidence and being kept up-to-date [25, 38,39,40]. Second, patients should be included in their development to ensure the tools are user-friendly and understandable [41]. Third, the impact on patient outcomes should be evaluated. Fourth, the conditions for appropriate use of tools in clinical practice should be realized, e.g. clinical teams should recognise the importance of SDM and should be trained in SDM [6, 42], and sufficient time should be available to use a tools for SDM during a clinical encounter [6, 43,44,45].

Conclusions

Only two tools for SDM in metastatic breast cancer care were positively evaluated on effectiveness and are currently available. These are developed to be used by patients before consulting the physician. None have been tested in well-designed studies. These tools show promising results in pilot studies and focus on different aspects of care. However, their effectiveness should be confirmed in well-designed studies before implementation in clinical practice. Innovation and development of SDM tools targeting clinicians as well as patients during a clinical encounter is recommended.

Abbreviations

- DA:

-

Decision aid

- GRADE:

-

Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

- SDM:

-

Shared decision-making

References

GLOBOCAN 2012: Estimated Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide in 2012. 2012. http://globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/fact_sheets_cancer.aspx (2012). Accessed 1 Feb 2017.

Lux MP, Bayer CM, Loehberg CR, Fasching PA, Schrauder MG, Bani MR, et al. Shared decision-making in metastatic breast cancer: discrepancy between the expected prolongation of life and treatment efficacy between patients and physicians, and influencing factors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;139:429–40.

Leighl NB, Butow PN, Tattersall MH. Treatment decision aids in advanced cancer: when the goal is not cure and the answer is not clear. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1759–62.

Partridge AH, Rumble RB, Carey LA, Come SE, Davidson NE, Di Leo A, et al. Chemotherapy and targeted therapy for women with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–negative (or unknown) advanced breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3307–29.

Elwyn G, Laitner S, Coulter A, Walker E, Watson P, Thomson R. Implementing shared decision making in the NHS. BMJ. 2010;341:c5146.

Légaré F, Ratté S, Gravel K, Graham ID. Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision-making in clinical practice: update of a systematic review of health professionals’ perceptions. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73:526–35.

Institute of Medicine. Delivering high-quality cancer care: charting a new course for a system in crisis. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2013.

Degner LF, Sloan JA. Decision making during serious illness: what role do patients really want to play? J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:941–50.

Keating NL, Guadagnoli E, Landrum MB, Borbas C, Weeks JC. Treatment decision making in early-stage breast cancer: should surgeons match patients’ desired level of involvement? J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1473–9.

Gaston CM, Mitchell G. Information giving and decision-making in patients with advanced cancer: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:2252–64.

Kehl KL, Landrum MB, Arora NK, Ganz PA, Van Ryn M, Mack JW, et al. Association of actual and preferred decision roles with patient-reported quality of care: shared decision making in cancer care. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:50–8.

Stacey D, Légaré F, Lewis K, Barry MJ, Bennett CL, Eden KB, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;Issue 4. Art. No.: CD001431. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub5

Kashaf MS, McGill E. Does shared decision making in cancer treatment improve quality of life? A systematic literature review. Med Decis Mak. 2015;35:1037–48.

Hargraves I, Montori VM. Decision aids, empowerment, and shared decision making. BMJ. 2014;349:g5811.

Stacey D, Bennett CL, Barry MJ, Col NF, Eden KB, Holmes-Rovner M, Thomson R. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;10(10).

Ozanne EM, Partridge A, Moy B, Ellis KJ, Sepucha KR. Doctor-patient communication about advance directives in metastatic breast cancer. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:547–53.

Elwyn G, Lloyd A, Joseph-Williams N, Cording E, Thomson R, Durand M-A, et al. Option grids: shared decision making made easier. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;90:207–12.

Stacey D, Légaré F, Lyddiatt A, Giguere AM, Yoganathan M, Saarimaki A, Tugwell P. Translating evidence to facilitate shared decision making: development and usability of a consult decision aid prototype. The Patient. 2016; 9(6):571–82.

Elwyn G, O'Connor A, Stacey D, Volk R, Edwards A, Coulter A, et al. Developing a quality criteria framework for patient decision aids: online international Delphi consensus process. BMJ. 2006;333:417.

Elwyn G, Edwards A, Hood K, Robling M, Atwell C, Russell I, et al. Achieving involvement: process outcomes from a cluster randomized trial of shared decision making skill development and use of risk communication aids in general practice. Fam Pract. 2004;21:337–46.

Whelan T, Gafni A, Charles C, Levine M. Lessons learned from the decision board: a unique and evolving decision aid. Health Expect. 2000;3:69–76.

Tang J, Shakespeare T, Lu J, Chan Y, Lee K, Wong L, et al. Patients’ preference for radiotherapy fractionation schedule in the palliation of symptomatic unresectable lung cancer. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2008;52:497–502.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:924–6.

Chiew KS, Shepherd H, Vardy J, Tattersall MH, Butow PN, Leighl NB. Development and evaluation of a decision aid for patients considering first-line chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer. Health Expect. 2008;11:35–45.

Oostendorp LJ, Ottevanger PB, van de Wouw AJ, Schoenaker IJ, de Graaf H, van der Graaf WT, et al. Expected survival with and without second-line palliative chemotherapy: who wants to know? Health Expect. 2015;18:2903–14.

Oostendorp LJM, Ottevanger PB, van de Wouw AJ, Honkoop AH, Los M, van der Graaf WTA, et al. Patients’ preferences for information about the benefits and risks of second-line palliative chemotherapy and their oncologist's awareness of these preferences. J Cancer Educ. 2016;31:443–8.

Smith TJ, Dow LA, Virago EA, Khatcheressian J, Matsuyama R, Lyckholm LJ. A pilot trial of decision aids to give truthful prognostic and treatment information to chemotherapy patients with advanced cancer. J Support Oncol. 2011;9:79.

Meropol NJ, Egleston BL, Buzaglo JS, Balshem A, Benson AB, Cegala DJ, et al. A web-based communication aid for patients with cancer. Cancer. 2013;119:1437–45.

Oostendorp LJM, Ottevanger PB, Donders ART, Wouw AJ, Schoenaker IJH, Smilde TJ, et al. Decision aids for second-line palliative chemotherapy: a randomised phase II multicentre trial. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2017;17:130.

Sepucha KR, Ozanne EM, Partridge AH, Moy B. Is there a role for decision aids in advanced breast cancer? Med Decis Mak. 2009;29:475–82.

Department of Health. Equity and excellence: liberating the NHS. London: National Health Service; 2010.

United States Federal Statute. The patient protection and affordable care act. Washington: US Government; 2010.

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care: National Statement on health literacy: taking action to improve safety and quality; 2014.

Chow S, Teare G, Basky G. Shared decision making: helping the system and patients make quality health care decisions. Saskatchewan: Health Quality Council; 2009.

Stiggelbout AM, Van der Weijden T, De Wit M, Frosch D, Légaré F, Montori VM, et al. Shared decision making: really putting patients at the Centre of healthcare. BMJ. 2012;344:e256.

Breslin M, Mullan RJ, Montori VM. The design of a decision aid about diabetes medications for use during the consultation with patients with type 2 diabetes. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73:465–72.

Elwyn G, Frosch D, Volandes AE, Edwards A, Montori VM. Investing in deliberation: a definition and classification of decision support interventions for people facing difficult health decisions. Med Decis Mak. 2010;30:701–11.

Joseph-Williams N, Newcombe R, Politi M, Durand M-A, Sivell S, Stacey D, et al. Toward minimum standards for certifying patient decision aids: a modified Delphi consensus process. Med Decis Mak. 2014;34:699–710.

Durand M-A, Witt J, Joseph-Williams N, Newcombe RG, Politi MC, Sivell S, et al. Minimum standards for the certification of patient decision support interventions: feasibility and application. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98:462–8.

Montori VM, LeBlanc A, Buchholz A, Stilwell DL, Tsapas A. Basing information on comprehensive, critically appraised, and up-to-date syntheses of the scientific evidence: a quality dimension of the international patient decision aid standards. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2013;13:S5.

Montori VM, Breslin M, Maleska M, Weymiller AJ. Creating a conversation: insights from the development of a decision aid. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e233.

Lloyd A, Joseph-Williams N, Edwards A, Rix A, Elwyn G. Patchy ‘coherence’: using normalization process theory to evaluate a multi-faceted shared decision making implementation program (MAGIC). Implement Sci. 2013;8:102.

Joseph-Williams N, Elwyn G, Edwards A. Knowledge is not power for patients: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of patient-reported barriers and facilitators to shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;94:291–309.

O’Brien MA, Ellis PM, Whelan TJ, Charles C, Gafni A, Lovrics P, et al. Physician-related facilitators and barriers to patient involvement in treatment decision making in early stage breast cancer: perspectives of physicians and patients. Health Expect. 2013;16:373–84.

Belcher VN, Fried TR, Agostini JV, Tinetti ME. Views of older adults on patient participation in medication-related decision making. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:298–303.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. dr. Glyn Elwyn for checking our search strategy.

Funding

LvV is funded by a Dutch Cancer Society Young Investigator Grant (Grant number: 10392). The other authors are not funded.

Availability of data and materials

Tools selected for this review were referenced in bibliography. All data extracted from the selected tools and studies were presented in the tables. There is no raw data to be made available.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study concept and design, the data analysis and interpretation, reviewed the final manuscript, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. IS and JK collected and extracted the data, and checked the quality of the data. The manuscript was prepared by IS and edited by JB, FS, LvV and JK.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable as no patients were involved. This manuscript is a review of available literature and tools.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix 1. Search strategy

Appendix 1. Search strategy

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Spronk, I., Burgers, J.S., Schellevis, F.G. et al. The availability and effectiveness of tools supporting shared decision making in metastatic breast cancer care: a review. BMC Palliat Care 17, 74 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-018-0330-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-018-0330-4