Abstract

Background

Shared decision-making (SDM) is poorly implemented in routine care, despite being promoted by health policies. No reviews have solely focused on an in-depth synthesis of the literature around organizational- and system-level characteristics (i.e., characteristics of healthcare organizations and of healthcare systems) that may affect SDM implementation. A synthesis would allow exploration of interventions to address these characteristics. The study aim was to compile a comprehensive overview of organizational- and system-level characteristics that are likely to influence the implementation of SDM, and to describe strategies to address those characteristics described in the literature.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review using the Arksey and O’Malley framework. The search strategy included an electronic search and a secondary search including gray literature. We included publications reporting on projects that promoted implementation of SDM or other decision support interventions in routine healthcare. We screened titles and abstracts, and assessed full texts for eligibility. We used qualitative thematic analysis to identify organizational- and system-level characteristics.

Results

After screening 7745 records and assessing 354 full texts for eligibility, 48 publications on 32 distinct implementation projects were included. Most projects (N = 22) were conducted in the USA. Several organizational-level characteristics were described as influencing the implementation of SDM, including organizational leadership, culture, resources, and priorities, as well as teams and workflows. Described system-level characteristics included policies, clinical guidelines, incentives, culture, education, and licensing. We identified potential strategies to influence the described characteristics, e.g., examples how to facilitate distribution of decision aids in a healthcare institution.

Conclusions

Although infrequently studied, organizational- and system-level characteristics appear to play a role in the failure to implement SDM in routine care. A wide range of characteristics described as supporting and inhibiting implementation were identified. Future studies should assess the impact of these characteristics on SDM implementation more thoroughly, quantify likely interactions, and assess how characteristics might operate across types of systems and areas of healthcare. Organizations that wish to support the adoption of SDM should carefully consider the role of organizational- and system-level characteristics. Implementation and organizational theory could provide useful guidance for how to address facilitators and barriers to change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Although recognized as ethically important and frequently included in healthcare policies [1], the practice of engaging patients in their healthcare decisions is infrequently implemented in routine care [2,3,4,5,6]. Research on shared decision-making (SDM) has identified this failure of implementation, but has focused primarily on the associated patient- and provider-level characteristics [7,8,9,10]. Studies of other practice-changing interventions have similarly identified implementation challenges, but in other areas, the search for solutions has extended to characteristics of healthcare delivery beyond the patient and clinician to the organizational characteristics and the system-level policies. How these findings from the implementation literature, and research on organizational- and system-level characteristics specifically, might affect efforts to implement SDM is not well known.

SDM is a widely recognized approach to cultivate patient-centered care [11, 12]. It is an approach where clinicians and patients share the best available evidence when faced with the task of making decisions, and where patients are supported to consider options and to achieve informed preferences [13]. SDM is a communicative process that can be supported by the use of decision aids, also called decision support interventions. In the last several years, there has been growing interest in advancing SDM in routine healthcare. In many countries, health policies include implementation of SDM. In a series of articles recently published on the development of activities to promote SDM in 22 different countries, it was shown that 19 countries have health policies that foster or even demand SDM implementation [1]. Despite this health policy commitment to SDM and its inclusion in a range of clinical practice guidelines, study results from other countries point towards poor implementation in routine clinical practice [2,3,4,5,6].

These results have led to work that attempts to explain the difficulty of implementing SDM in routine care. Research on barriers to and facilitators of SDM mostly identifies contributing factors at the individual level of care, i.e., characteristics of individual patients, clinicians, or the direct patient-clinician interaction [8,9,10]. Two systematic reviews on perceived barriers and facilitators of SDM implementation not only reported individual factors (i.e., knowledge, attitudes, and behavior), but also included a few environmental factors (e.g., time, resources) [10, 14]. A similarly narrow focus on attitudes, skills, and behavior of individual clinicians and patients manifest in most interventions developed for SDM [15]. Recent work has acknowledged the importance of taking organizational-level characteristics into account. These are the characteristics of specific healthcare organizations (i.e., entities that deliver healthcare, e.g., hospitals, practices) that affect the implementation of SDM. For example, Müller and colleagues [16] highlighted the importance of organizational culture, leadership support, and changes in workflow structures to better implement SDM in cancer care. Additionally, little is known about the role of system-level characteristics in the implementation of SDM. These are the characteristics of the healthcare system that guide the work of healthcare organizations (i.e., the political, economic, and social context in which healthcare organizations are embedded, e.g., policies and legislation) [17].

Research on the implementation of health innovations has shown that it is crucial to take into account characteristics of healthcare institutions and of the healthcare system at large in order to change practice [18,19,20]. Those characteristics may otherwise function as powerful barriers to implementing SDM at the individual encounter level. Nevertheless, implementation strategies are often targeted to change knowledge, attitudes, and behavior of individual providers [21], hindered perhaps, by the lack of measures available to assess system-level characteristics [18]. Similarly, in research on SDM, no studies have focused solely on an in-depth synthesis of the literature around organizational- and system-level characteristics that may influence the implementation of SDM in routine care. A greater understanding of the organizational- and system-level characteristics that could impede or support implementation of SDM in routine care may be helpful in finding ways to address these characteristics in implementation strategies. Thus, the aim of this scoping review is to compile a comprehensive overview of experiences with organizational- and system-level characteristics in implementing SDM in routine care. The following research questions guided this scoping review:

-

1.

What experiences with organizational- and system-level characteristics are reported in SDM implementation projects?

-

2.

What strategies to address these characteristics are discussed in the literature?

Methods

Design

We performed a scoping review rather than a systematic review due to the broad nature of our research questions, the young field of SDM research, and our anticipation of high variation in study designs and methodologies [22]. We used the definition of scoping review given by Colquhoun and colleagues: “a form of knowledge synthesis that addresses an exploratory research question aimed at mapping key concepts, types of evidence, and gaps in research related to a defined area or field by systematically searching, selecting, and synthesizing existing knowledge” [23].

Protocol

We developed our protocol based on the Arksey and O’Malley framework [22], as well as on subsequently published guidance on how to conduct scoping reviews [24,25,26]. The final version of the protocol can be found in Additional file 1.

Eligibility criteria

We included publications that reported on the results of projects, quality improvement programs, or studies that aimed to implement SDM, decision aids (i.e., tools for use inside or outside the clinical encounter [27]) or other decision support interventions (i.e., mediated by more interactive or social technologies [27]) in routine healthcare through a certain implementation strategy or effort. To be included, these full texts also needed to report on organizational-level and/or system-level characteristics described to influence the implementation, and/or describe strategies that might address organizational-level and/or system-level characteristics. Opinion pieces, reviews, and study protocols were excluded, but reviews were used in the secondary search process, as described below. The full list of inclusion and exclusion criteria, specifying concepts and contexts of this scoping review, is displayed in Table 1.

Search strategy

We performed an electronic literature search in Medline, CINAHL, and Web of Science Core Collection. We included articles published between January 1997, the year in which Charles and colleagues described the concept of SDM in their seminal article [28], and October 10, 2016. The search was limited to articles published in English or German, as these were the only languages spoken by a minimum of two members of the review team. Details of the search strategies in the different databases can be found in Additional file 2.

Our primary electronic search was complemented by a comprehensive secondary search strategy. All records excluded through criterion E2 (systematic, scoping, and structured literature reviews) [10, 14, 15, 29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42] were checked to see whether they reported on studies that could potentially be relevant for this scoping review. Subsequently, the reference lists of six of these reviews [10, 15, 29, 36, 39] were assessed for eligibility. Furthermore, two books were searched for chapters meeting the inclusion criteria [43, 44], and a gray literature search was conducted on a range of websites listed in Additional file 3.

Study selection process

We imported all identified records into reference management software (Endnote) and removed duplicates. First, IS and a second reviewer (PH, AL, or RPM) performed an independent title and abstract screening to check for potential inclusion of records. A record was included into the next step of full text assessment if at least one reviewer deemed it appropriate. Second, full text assessment was conducted. To ensure quality and consistency of full text assessments, the first 20% of randomly selected full texts were assessed by two team members (IS and PH or IS and AL). In 83% of the cases, the team members agreed on inclusion or exclusion. Discrepant assessments were subsequently discussed by the team members. This process led to minor revisions in the exact wording of the inclusion and exclusion criteria and an instruction of how to use the criteria. Then, another round of double assessment using another set of 10% of randomly selected full texts was conducted, leading to agreement in 93% of the cases. The subsequent assessment of the remaining 70% of full texts was conducted by one reviewer (IS) using a conservative approach. Whenever the single assessor (IS) was in slight doubt about whether to include or exclude a full text, a second reviewer was assigned to assess that full text, and final decision regarding inclusion was made by discussion. This procedure was done for a total of 14 full texts.

Data extraction

We extracted general information on each study and specific information related to the research questions. We extracted any information on experiences related to organizational- and system-level characteristics and potential strategies to address them. As we wanted to give a broad overview, we extracted all information on experiences reported in the publications, including experiences derived from results (empirical) and from the interpretation of results (opinion-based). The number of full texts identified and selected is described using the PRISMA flowchart. The initial data extraction sheet was developed by one team member (IS), based on experience from other reviews [12, 15, 45, 46]. It was pilot tested by IS and AL, using two included full texts [47, 48]. We compared the extracted data and found only very minor differences in the level of detail of the respective extractions. As a result, the extraction sheet was slightly revised (e.g., by adding definitions of what to extract). Further data extraction was conducted by one person (either AL or IS). Whenever one data extractor was in doubt regarding what to extract for a certain category, the second person checked the full text and both met to discuss agreement on what to extract.

Methodological quality appraisal

We did not appraise the methodological quality or risk of bias of the included studies, which is consistent with guidance on the conduct of scoping reviews [22].

Synthesis

We conducted a descriptive analysis of characteristics of the included studies (e.g., types of study design, years of publication) as well as a qualitative thematic analysis of the organizational- and system-level characteristics identified in the studies. We decided to report what other studies reported as influential characteristics, rather than classify them as barriers or facilitators. This analysis drew on principles of qualitative content analysis described by Hsieh and Shannon [49] and consisted of the following steps: first, two researchers (AL and IS) read the entire set of extracted data to gain an overview. Second, one researcher (AL) coded the material (initial inductive coding). Third, comments by a second researcher (IS) led to adaptation of the coding system. Fourth, the revised codes were organized into a coding system using clusters and subcategories, agreed in discussion with two other team members (GE and SK). Fifth, the material was re-coded by one researcher (AL) using the established coding system. Sixth, the re-coded material was cross-checked by a second researcher (IS) and minimal changes were made in discussion (IS and AL). Potential strategies mentioned in the publications to address organizational- and system- level characteristics were synthesized and mapped onto identified characteristics in a team discussion (IS, AL, GE). No qualitative data analysis software was used. Analyses were conducted on the level of distinct implementation projects, i.e., publications reporting on the same implementation project were grouped under one single project ID.

Results

Included studies

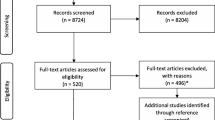

After screening 7745 titles and abstracts for eligibility, and checking 354 full texts against the inclusion and exclusion criteria, we included 48 full texts (see Fig. 1). Reasons for exclusion of full texts are displayed in Table 1. The included full texts report on a total of 32 distinct implementation projects. While most projects were only reported in a single publication, several projects were described in two or more publications. Twenty-two projects were conducted in the USA, and 26 projects focused on the implementation of decision aids or other forms of decision support. Projects focused on various settings and a broad range of decisional contexts. Table 2 gives an overview on the included projects and publications.

Flow chart of study selection. *Reasons for exclusion: I1: 2 in total (1 full text from primary search, 1 full text from secondary search). I2: none. I3: 33 in total (29 full texts from primary search, 4 full texts from secondary search). I4: 157 in total (113 full texts from primary search, 44 full texts from secondary search). I5: 10 in total (8 full texts from primary search, 2 full texts from secondary search). E1: 61 in total (58 full texts from primary search, 3 full texts from secondary search). E2: 22 in total (17 full texts from primary search, 5 full texts from secondary search). E3: 21 in total (20 full texts from primary search, 1 full texts from secondary search)

Characteristics influencing SDM implementation

Figure 2 gives an overview of the identified characteristics.

Organizational-level characteristics

Table 3 displays the organizational-level characteristics reported in the included full texts as influencing the implementation of SDM, decision aids, or other decision support interventions. The table includes descriptions of all identified characteristics. Six main categories of organizational characteristics were described in the included studies: organizational leadership, culture, teamwork, resources, priorities, and workflows. Five of the six main categories also included several subcategories of organizational-level characteristics; for example, the category “organizational resources” included the subcategories time (that healthcare providers have per patient), financial resources (that are available for certain activities within a healthcare organization), workforce (i.e., employees available for and assigned to certain activities within a healthcare organization), and space (i.e., room available for certain activities within a healthcare organization). Both the availability of resources within an organization and organizational workflows (e.g., patient information dissemination strategies, scheduling routines, use of the electronic health record) were described to have influenced SDM implementation efforts in over three quarters of the projects, and facets of the organizational culture and teamwork within an organization were reported in only a third of the projects (see column “Project IDs” in Table 3).

System-level characteristics

While many organizational characteristics were identified in the included full texts, only four main categories of characteristics of the healthcare system were described: incentives (i.e., the role of payment models and accreditation/certification criteria), policies and guidelines (i.e. the role of healthcare legislation and clinical practice guidelines), culture of healthcare delivery, and healthcare provider education and licensing. Table 4 gives an overview of the characteristics of the healthcare system that were reported as influencing implementation. The table includes descriptions of all identified characteristics. While only four projects reported that the culture of healthcare delivery influenced SDM implementation, about one third of the projects reported that incentives, policies and guidelines, and healthcare professional education and licensing influenced SDM implementation (see column “Project IDs” in Table 4).

Strategies to address organizational- and system-level characteristics

A range of possible strategies to address organizational- and system-level characteristics and thereby potentially foster SDM implementation were discussed in the publications and mapped onto the identified characteristics. They are displayed in Table 5. Similar to the results on experienced characteristics, most proposed strategies focused on the organizational level. Most studies identified workflow as an organizational-level characteristic influencing SDM implementation and also generated potential strategies to tackle that characteristic. Few strategies were suggested to change organizational culture [50,51,52], which was also described in fewer studies. A large range of potential strategies were also described to promote leadership activities that might facilitate SDM implementation (see full list in Table 5). At the system-level, fewer strategies were described. Suggestions included changes in payment models [53,54,55], legislation [51, 56, 57], and health professional education [51, 58,59,60].

Discussion

Summary of the review findings

We described a broad range of organizational- and system-level characteristics that were experienced as influencing the implementation of SDM in routine care, as well as strategies to potentially address those characteristics. Included studies reported more often on characteristics influencing the organizational level than the health system level. The reported organizational characteristics are strongly influenced by health system characteristics; for example, the amount of time that a HCP has for a patient’s visit is linked to payment models, the organizational culture is influenced by the general culture of healthcare delivery, and the leadership decisions within an organization are affected by policies, payment models, and accreditation criteria. As the identified characteristics can be barriers, facilitators or both barriers and facilitators to SDM implementation, we described them in a value-neutral way.

Strengths and limitations

We extracted reports from implementation studies described in any part of the included publications. Our analyses therefore cannot differentiate between experiences based on results and those reflecting interpretation of results. However, for a young research field, we believe this broad scoping review is an important first step to gaining an overview of the topic.

A second limitation is that the primary search was limited to three electronic databases, so we might have missed relevant publications. However, we prioritized sensitivity in our electronic search, which is reflected by the high number of screened abstracts, to identify most relevant work. Furthermore, we conducted an extensive secondary search, including gray literature to find more work not indexed in the electronic databases searched. Another limitation is that we did not conduct a full double assessment and double data extraction. However, we did our best to minimize error by consulting with a second reviewer whenever there was the slightest doubt. A main strength of this review is that it is the first of its kind to focus solely on the impact of organizational and system characteristics on the implementation of SDM. In previous work, the focus had mainly been on the individual clinician-patient level, and organizational- and system-level characteristics had not been examined in depth [10, 14]. Furthermore, it was conducted in an inter-professional and international team.

Comparison to previous work

First, these findings need to be compared to previous work on SDM. Our results reinforce prior calls for better coordination of care, engagement of non-physician personnel, and the use of the electronic health record (EHR) to implement SDM in previous work [61]. The suggestions to use clinical practice guidelines, postgraduate training, and accreditation as means to better implement SDM [5] are also reflected in the data collected in this scoping review. Many of the characteristics identified in this review have been discussed in trials of SDM interventions or decision aids, in studies of clinicians’ perceptions, or in opinion pieces, but this is the first piece of work looking at characteristics experienced in actual implementation studies.

Second, the results need to be compared to more general work in healthcare implementation science, beyond the case of SDM as a particular innovation to implement. Implementation frameworks and conceptual models like the one postulated by Greenhalgh and colleagues [20] or the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) [19] have described elements in the inner and outer settings to influence implementation. Our results found a range of very similar characteristics on the organizational level to the ones described in the inner setting, e.g., communication and culture within an organization, leadership engagement, resources, and priorities. However, some of the characteristics we found (e.g., workflows) were not described in the CFIR [19]. One could hypothesize that these aspects are more focused around decision aid implementation and therefore not included in a more general implementation framework. Similarly, several of our system-level characteristics map well onto the CFIR’s outer setting (i.e., aspects around policies, guidelines, and incentives), but the culture of the healthcare system and education and licensing of healthcare professionals cannot be found in the framework [19]. Furthermore, a systematic review on determinants of implementation of preventive interventions on patient handling identified a total of 45 environmental barriers and facilitators [62] that overlap with experienced organizational characteristics identified in our scoping review, particularly the availability of resources, leadership support, and the organization of workflows. Overall, our results in the field of SDM display many similarities with the characteristics described in implementation science frameworks and in other fields of health innovation. However, as we also identify characteristics less described in implementation science literature, we believe it is important to not to be restricted by such frameworks, but enrich them with derived empirical evidence.

Third, some of the strategies recommended by the included projects to intervene on characteristics influencing SDM implementation (Table 5) are vague and require further specification and tailoring to a specific context [63]. For example, some of the strategies that fall into the leadership category could benefit from distinguishing which level of leadership should take action for which strategy. While the people in a governing board of an organization might be the ones to revise mission statements, executive leadership, and departmental management might be the ones who create a culture that supports SDM [64]. Furthermore, all other categories identified as organizational-level characteristics, despite not specifying who should be in charge of making specific changes, imply that organizational leadership is the actor here. Although it is not specified, for example, who should implement multidisciplinary teams or create an SDM coordinator position, there is an implicit assumption that these are leadership tasks. Beyond looking at implementation literature, it might therefore be worthwhile for stakeholders working on SDM implementation to look into organizational theories in healthcare [65], e.g., on the effective organization of healthcare teams or on strategies to restructure healthcare organizations.

Implications and suggestions for further work

As healthcare systems are complex and composed of components that act nonlinearly [66], a certain identified characteristic can be a facilitator to one stakeholder and a barrier to another. Therefore, more work is needed to move beyond the descriptive stage of this review, especially as differences in the numbers of studies reporting on certain characteristics do not necessarily mean that those characteristics are the most important. Similarly to Koppelaar et al. [62], we believe there is a need to quantify the influence of the identified characteristics, especially as this scoping review’s broad nature is not distinguishing between experiences based on results of implementation studies and interpretation of those results. By evaluating the influencing characteristics in implementation studies, we could analyze interactions between characteristics and find out which of them predict implementation outcomes [18].

As the included studies were predominantly from the USA, future work needs to assess the importance of the identified characteristics in different healthcare systems with variation in financing, coverage, spending, utilization, capacity, and performance [67], as well as different fields of healthcare (e.g., cancer care, mental healthcare). This would help to gain a more specific insight that could foster prioritization of the most important characteristics in a particular setting and strategies to address them.

Conclusion

Although infrequently studied, organizational- and system-level characteristics appear to play a role in the failure to implement SDM in routine care. A wide range of characteristics described as supporting and inhibiting implementation were identified. Future studies should quantify these characteristics’ differential impact on SDM implementation, their likely interactions, and how different characteristics might operate across types of healthcare systems and areas of healthcare. Healthcare organizations that wish to support the adoption of SDM should carefully consider the role of organizational- and system-level characteristics. Implementation and organizational theory could provide useful guidance for how to address facilitators and barriers to change.

Abbreviations

- CFIR:

-

Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research

- EHR:

-

Electronic health record

- RCTs:

-

Randomized controlled trials

- SDM:

-

Shared decision-making

References

Härter M, Moumjid N, Cornuz J, Elwyn G, van der Weijden T. Shared decision making in 2017: international accomplishments in policy, research and implementation. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes. 2017;123:1–5.

Coulter A. Implementing shared decision making in the UK: a report for the Health Foundation. London: Health Foundation; 2009.

Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Self-reported use of shared decision-making among breast cancer specialists and perceived barriers and facilitators to implementing this approach. Health Expect. 2004;7:338–48.

Foundation for Informed Medical Decision Making. Informing and involving patients in medical decisions: the primary care physicians’ perspective. Findings from a national survey of physicians. Boston: Foundation for Informed Medical Decision Making; 2009.

Stiggelbout AM, van der Weijden T, de Wit MPT, Frosch D, Légaré F, Montori VM, et al. Shared decision making: really putting patients at the centre of healthcare. BMJ. 2012;344:e256.

Vogel BA, Helmes AW, Hasenburg A. Concordance between patients’ desired and actual decision-making roles in breast cancer care. Psychooncology. 2008;17:182–9.

The Health Foundation. Implementing shared decision making. Clinical teams’ experiences of implementing shared decision making as part of the MAGIC programme. Learning report. London: The Health Foundation; 2013.

Shepherd HL, Tattersall MH, Butow PN. The context influences doctors’ support of shared decision-making in cancer care. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:6–13.

Shepherd HL, Tattersall MH, Butow PN. Physician-identified factors affecting patient participation in reaching treatment decisions. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1724–31.

Légaré F, Ratté S, Gravel K, Graham ID. Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision-making in clinical practice: update of a systematic review of health professionals’ perceptions. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73:526–35.

Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making - the pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:780–1.

Scholl I, Zill JM, Härter M, Dirmaier J. An integrative model of patient-centeredness - a systematic review and concept analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e107828.

Elwyn G, Laitner S, Coulter A, Walker E, Watson P, Thomson R. Implementing shared decision making in the NHS. BMJ. 2010;341:971–5.

Gravel K, Légaré F, Graham ID. Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision-making in clinical practice: a systematic review of health professionals’ perceptions. Implement Sci. 2006;1:16.

Elwyn G, Scholl I, Tietbohl C, Mann M, Edwards AG, Clay C, et al. “Many miles to go …”: a systematic review of the implementation of patient decision support interventions into routine clinical practice. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2013;13(Suppl 2):S14.

Müller E, Hahlweg P, Scholl I. What do different stakeholders need to better implement shared decision making in cancer care? A qualitative needs assessment. Acta Oncol (Madr). 2016;55:1484–91.

Elwyn G, Frosch DL, Kobrin S. Implementing shared decision-making: consider all the consequences. Implement Sci. 2015;11:114.

Chaudoir S, Dugan A, Barr CHI. Measuring factors affecting implementation of health innovations: a systematic review of structural, organizational, provider, patient, and innovation level measures. Implement Sci. 2013;8:22.

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:40–55.

Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004;82:581–629.

Grol RPTM, Bosch MC, Hulscher MEJL, Eccles MP, Wensing M. Planning and studying improvement in patient care: the use of theoretical perspectives. Milbank Q. 2007;85:93–138.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32.

Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O’Brien KK, Straus S, Tricco AC, Perrier L. Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:1291–4.

Daudt HML, van Mossel C, Scott SJ. Enhancing the scoping study methodology: a large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:48.

Khalil H, Peters M, Godfrey CM, Mcinerney P, Soares CB, Parker D. An evidence-based approach to scoping reviews. Worldviews Evid-Based Nurs. 2016;13:118–23.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:69.

Elwyn G, Frosch D, Volandes AE, Edwards A, Montori VM. Investing in deliberation: a definition and classification of decision support interventions for people facing difficult health decisions. Med Decis Mak. 2010;30:701–11.

Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Soc Sci Med. 1997;44:681–92.

Herrmann A, Mansfield E, Hall AE, Sanson-Fisher R, Zdenkowski N. Wilfully out of sight? A literature review on the effectiveness of cancer-related decision aids and implementation strategies. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2016;16:36.

Joseph-Williams N, Elwyn G, Edwards A. Knowledge is not power for patients: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of patient-reported barriers and facilitators to shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;94:291–309.

Kane HL, Halpern MT, Squiers LB, Treiman KA, McCormack LA. Implementing and evaluating shared decision making in oncology practice. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:377–88.

Légaré F, Ratté S, Stacey D, Kryworuchko J, Gravel K, Graham ID, et al. Interventions for improving the adoption of shared decision making by healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;5:Cd006732.

Légaré F, Turcotte S, Stacey D, Ratté S, Kryworuchko J, Graham ID. Patients’ perceptions of sharing in decisions. Patient-Patient-Centered Outcomes Res. 2012;5:1–19.

Lenz M, Buhse S, Kasper J, Kupfer R, Richter T, Mühlhauser I. Entscheidungshilfen für Patienten. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109:401–8.

Murray MA, Brunier G, Chung JO, Craig LA, Mills C, Thomas A, et al. A systematic review of factors influencing decision-making in adults living with chronic kidney disease. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;76:149–58.

Obeidat R, Finnell DS, Lally RM. Decision aids for surgical treatment of early stage breast cancer: a narrative review of the literature. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85:e311–21.

Obeidat RF, Homish GG, Lally RM. Shared decision making among individuals with cancer in non-western cultures: a literature review. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2013;40:454–63.

Renzi C, Goss C, Mosconi P. Efforts to link declarations to actions: Italian experiences of shared decision making in clinical settings. Ann DI Ig. 2008;20:589–93.

Shultz CG, Jimbo M. Decision aid use in primary care: an overview and theory-based framework. Fam Med. 2015;47:679–92.

Thompson-Leduc P, Clayman ML, Turcotte S, Légaré F. Shared decision-making behaviours in health professionals: a systematic review of studies based on the theory of planned behaviour. Health Expect. 2015;18:754–74.

Waljee JF, Rogers MAM, Alderman AK. Decision aids and breast cancer: do they influence choice for surgery and knowledge of treatment options? J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1067–73.

Waterworth S, Gott M. Decision making among older people with advanced heart failure as they transition to dependency and death. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2010;4:238–42.

Elwyn G, Grande SW, Hoffer Gittell J, Collins Vidal D, Godfrey MM, editors. Are we there yet? Case studies of implementing decision support for patients. Hanover: The Dartmouth Center for Health Care Delivery Science and The Dartmouth Institute for Healthcare Policy and Clinical Practice; 2013.

Elwyn G, Edwards A, Thompson R. Shared decision-making in health care. Achieving evidence-based patient choice. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2016.

Barr PJ, Scholl I, Bravo P, Faber MJ, Elwyn G, McAllister M. Assessment of patient empowerment - a systematic review of measures. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0126553.

Scholl I, Van Loon MK, Sepucha K, Elwyn G, Légaré F, Härter M, et al. Measurement of shared decision making - a review of instruments. Zeitschrift fur Evidenz, Fortbildung und Qualitat im Gesundheitswesen. 2011;105:313–24.

Abrines-Jaume N, Midgley N, Hopkins K, Hoffman J, Martin K, Law D, et al. A qualitative analysis of implementing shared decision making in child and adolescent mental health services in the United Kingdom: stages and facilitators. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2016;21:19–31.

Belkora JK, Volz S, Teng AE, Moore DH, Loth MK, Sepucha KR. Impact of decision aids in a sustained implementation at a breast care center. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86:195–204.

Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–88.

Frosch DL, Singer KJ, Timmermans S. Conducting implementation research in community-based primary care: a qualitative study on integrating patient decision support interventions for cancer screening into routine practice. Health Expect. 2011;14(SUPPL. 1):73–84.

King J, Moulton B. Group health’s participation in a shared decision-making demonstration yielded lessons, such as role of culture change. Health Aff. 2013;32:294–302.

Hsu C, Liss DT, Westbrook EO, Arterburn D. Incorporating patient decision aids into standard clinical practice in an integrated delivery system. Med Decis Mak. 2013;33:85–97.

Tapp H, Kuhn L, Alkhazraji T, Steuerwald M, Ludden T, Wilson S, et al. Adapting community based participatory research (CBPR) methods to the implementation of an asthma shared decision making intervention in ambulatory practices. J Asthma. 2014;51:380–90.

Swieskowski D. Shared decision making in primary care. In: Research & Implementation Report. Boston: Informed Medical Decisions Foundation; 2011. p. 30–4.

Conrad D. Shared decision making demonstration project. In: Research & Implementation Report. Boston: Informed Medical Decisions Foundation; 2011. p. 60–3.

Stacey D, Vandemheen KL, Hennessey R, Gooyers T, Gaudet E, Mallick R, et al. Implementation of a cystic fibrosis lung transplant referral patient decision aid in routine clinical practice: an observational study. Implement Sci. 2015;10:17.

Lewis CL, McDonald S, Brenner A, Waters M, Colford C, Young-Wright K, et al. Implementing tailored decision support using a patient health survey. In: Elwyn G, Grande SW, Hoffer Gittell J, Godfrey MM, Collins Vidal D, editors. Are we there yet? Case studies of implementing decision support for patients. 1st ed. Hanover: The Dartmouth Center for Health Care Delivery Science and The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice; 2013. p. 77–85.

King E, Taylor J, Williams R, Vanson T. The MAGIC programme: evaluation an independent evaluation of the MAGIC (making good decisions in collaboration) improvement programme. London: The Health Foundation; 2013.

Garden J. Implementing an informed decision-making programme for urology patients. J Commun Healthc. 2008;1:297–310.

Newsome A, Sieber W, Smith M, Lillie D. If you build it, will they come? A qualitative evaluation of the use of video-based decision aids in primary care. Fam Med. 2012;44:26–31.

Légaré F, Witteman HO. Shared decision making: examining key elements and barriers to adoption into routine clinical practice. Health Aff. 2013;32:276–84.

Koppelaar E, Knibbe JJ, Miedema HS, Burdorf A. Determinants of implementation of primary preventive interventions on patient handling in healthcare: a systematic review. Occup Environ Med. 2009;66:353–60.

Bosch M, Van Der Weijden T, Wensing M, Grol R. Tailoring quality improvement interventions to identified barriers: a multiple case analysis. J Eval Clin Pract. 2007;13:161–8.

Nelson WA, Donnellan JJ, Elwyn G. Implementing shared decision making: an organizational imperative. In: Elwyn G, Edwards A, Thompson R, editors. Shared decision making in health care: achieving evidence-based patient choice. 3rd ed. Hanover: The Dartmouth Center for Health Care Delivery Science and The Dartmouth Institute for Healthcare Policy and Clinical Practice; 2016. p. 24–9.

Birken SA, Bunger AC, Powell BJ, Turner K, Clary AS, Klaman SL, et al. Organizational theory for dissemination and implementation research. Implement Sci. 2017;12:62.

Lipsitz LA. Understanding health care as a complex system. JAMA. 2012;308:243–4.

Mossialos E, Wenzel M, Osorn R, Sarnak D. 2015 international profiles of health care systems. New York: The Commonwealth Fund; 2015.

Andrews AO, Kearing SA, Vidal DC. Case study: changing culture and delivery to achieve shared decision making at Dartmouth Hitchcock medical center, New Hampshire. In: Elwyn G, Edwards A, Thompson R, editors. Third edit. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2016. p. 204–9.

Berg S, Collins Vidal D, Clay K. Epidemiology of shared decision making. In: Research & Implementation Report. Boston: Informed Medical Decisions Foundation; 2011. p. 8–10.

Friedberg MW, Van Busum K, Wexler R, Bowen M, Schneider EC. A demonstration of shared decision making in primary care highlights barriers to adoption and potential remedies. Health Aff. 2013;32:268–75.

Arterburn D, Westbrook EO, Hsu C. Case study: the shared decision making story at group health. In: Elwyn G, Edwards A, Thompson R, editors. Shared decision making in health care: achieving evidence-based patient choice. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2016. p. 190–6.

Hsu C, Liss DT, Westbrook EO, Arterburn D. Shared decision making at group health: distribution patient decision support and engaging providers. In: Elwyn G, Grande SW, Hoffer Gittell J, Godfrey MM, Collins Vidal D, editors. Are we there yet? Case studies of implementing decision support for patients. 1st ed. Hanover: The Dartmouth Center for Health Care Delivery Science and The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice; 2013. p. 45–56.

Korsen N. Implementing use of decision aids in primary care practice. In: Research & Implementation Report. Boston: Informed Medical Decisions Foundation; 2011. p. 20–4.

Belkora JK, Loth MK, Chen DF, Chen JY, Volz S, Esserman LJ. Monitoring the implementation of consultation planning, recording, and summarizing in a breast care center. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73:536–43.

Belkora JK, Teng A, Volz S, Loth MK, Esserman LJ. Expanding the reach of decision and communication aids in a breast care center: a quality improvement study. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;83:234–9.

Belkora J, Volz S, Loth M, Teng A, Zarin-Pass M, Moore D, et al. Coaching patients in the use of decision and communication aids: RE-AIM evaluation of a patient support program. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:209.

Belkora J, Edlow B, Aviv C, Sepucha K, Esserman L. Training community resource center and clinic personnel to prompt patients in listing questions for doctors: follow-up interviews about barriers and facilitators to the implementation of consultation planning. Implement Sci. 2008;3:6.

Brackett C, Kearing S, Cochran N, Tosteson ANA, Blair BW. Strategies for distributing cancer screening decision aids in primary care. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;78:166–8.

Clay K, Grande SW, DuBois C, Tomek I, Mastanduno MP. Integration challenges: loss of existing patient decision support system when a new electronic health record arrives. In: Elwyn G, Grande SW, Hoffer Gittell J, Godfrey MM, Collins Vidal D, editors. Are we there yet? Case studies of implementing decision support for patients. 1st ed. Hanover: The Dartmouth Center for Health Care Delivery Science and The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice; 2013. p. 87–97.

Elwyn G, Thomson R. Implementing shared decision making in the United Kingdom: lessons from the making good decisions in collaboration (MAGIC) program. In: Elwyn G, Grande SW, Hoffer Gittell J, Godfrey MM, Vidal DC, editors. Are we there yet? Case studies of implementing decision support for patients. 1st ed. Hanover: The Dartmouth Center for Health Care Delivery Science and The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice; 2013. p. 23–34.

Lloyd A, Joseph-Williams N, Edwards A, Rix A, Elwyn G. Patchy “coherence”: using normalization process theory to evaluate a multi-faceted shared decision making implementation program (MAGIC). Implement Sci. 2013;8:102.

Lloyd A, Joseph-Williams N. Case study: different outcomes from different approaches - experience from the Cardiff MAGIC programme. In: Elwyn G, Edwards A, Thompson R, editors. Shared decision making in health care: achieving evidence-based patient choice. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2016. p. 197–203.

Elwyn G, Rix A, Holt T, Jones D. Why do clinicians not refer patients to online decision support tools? Interviews with front line clinics in the NHS. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e001530.

Feibelmann S, Yang TS, Uzogara EE, Sepucha K. What does it take to have sustained use of decision aids? A programme evaluation for the breast cancer initiative. Health Expect. 2011;14(SUPPL. 1):85–95.

Fortnum D, Smolonogov T, Walker R, Kairaitis L, Pugh D. My kidneys, my choice, decision aid: supporting shared decision making. J Ren Care. 2015;41:81–7.

Uy V, May SG, Tietbohl C, Frosch DL. Barriers and facilitators to routine distribution of patient decision support interventions: a preliminary study in community-based primary care settings. Health Expect. 2014;17:353–64.

Lin GA, Halley M, Rendle KAS, Tietbohl C, May SG, Trujillo L, et al. An effort to spread decision aids in five California primary care practices yielded low distribution, highlighting hurdles. Health Aff. 2013;32:311–20.

May SG, Tietbohl C, Frosch DL. Implementing decision support and shared decision making: steps toward culture change. In: Elwyn G, Grande SW, Hoffer Gittell J, Godfrey MM, Collins Vidal D, editors. Are we there yet? Case studies of implementing decision support for patients. 1st ed. Hanover: The Dartmouth Center for Health Care Delivery Science and The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice; 2013. p. 35–44.

Tietbohl CK, Rendle KAS, Halley MC, May SG, Lin GA, Frosch DL. Implementation of patient decision support interventions in primary care. Med Decis Mak. 2015;35:987–98.

Wirrmann E, Askham J. Implementing patient decision aids in urology — final report. Oxford; 2006.

Holmes-Rovner M, Valade D, Orlowski C, Draus C, Nabozny-Valerio B, Keiser S. Implementing shared decision making in routine practice: barriers and opportunities. Health Expect. 2000;3:182–91.

Holmes-Rovner M, Kelly-Blake K, Dwamena F, Dontje K, Henry RC, Olomu A, et al. Shared decision making guidance reminders in practice (SDM-GRIP). Patient Educ Couns. 2017;85:219–24.

Julian TB. Nurse navigator program integration. In: Research & Implementation Report. Boston: Informed Medical Decisions Foundation; 2011. p. 6–7.

Miller KM, Brenner A, Griffith JM, Pignone MP, Lewis CL. Promoting decision aid use in primary care using a staff member for delivery. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86:189–94.

McGrail K, Karmally R, Kiwalker S. AHRQ SHARE approach training and implementation success story: Rochester regional health system uses shared decision making to improve patient care. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2016.

Mollicone D, Pulliam J, Lacson E. The culture of education in a large dialysis organization: informing patient-centered decision making on treatment options for renal replacement therapy. Semin Dial. 2013;26:143–7.

Morrissey L, Elwyn G. Step-by-step using a community effort: implementing patient decision support in Stillwater, Minnesota. In: Elwyn G, Grande SW, Hoffer Gittell J, Godfrey MM, Collins Vidal D, editors. Are we there yet? Case studies of implementing decision support for patients. 1st ed. Hanover: The Dartmouth Center for Health Care Delivery Science and The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice; 2013. p. 57–65.

Morrissey L, Michels N. Assessing the effectiveness of decision support in primary care. In: Research & Implementation Report. Boston: Informed Medical Decisions Foundation; 2011. p. 44–6.

Pasternack I, Saalasti-Koskinen U, Mäkelä M. Decision aid for women considering breast cancer screening. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2011;27:357–62.

Sepucha KR, Simmons LH, Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S, Licurse AM, Chaguturu SK. Ten years, forty decision aids, and thousands of patient uses: shared decision making at Massachusetts General Hospital. Health Aff. 2016;35:630–6.

Simmons L, Leavitt L, Sepucha K. Case study: letting patients decide—a novel distribution strategy in primary care, Massechusetts General Hospital. In: Elwyn G, Edwards A, Thompson R, editors. Shared decision making in health care: achieving evidence-based patient choice. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2016. p. 210–4.

Silvia KA, Ozanne EM, Sepucha KR. Implementing breast cancer decision aids in community sites: barriers and resources. Health Expect. 2008;11:46–53.

Silvia KA, Sepucha KR. Decision aids in routine practice: lessons from the breast cancer initiative. Health Expect. 2006;9:255–64.

Stacey D, Pomey M-P, O’Connor AM, Graham ID. Adoption and sustainability of decision support for patients facing health decisions: an implementation case study in nursing. Implement Sci. 2006;1:17.

Stacey D, Chambers SK, Jacobsen MJ, Dunn J. Overcoming barriers to cancer-helpline professionals providing decision support for callers: an implementation study. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;35:961–9.

Stacey D, Taljaard M, Smylie J, Boland L, Breau RH, Carley M, et al. Implementation of a patient decision aid for men with localized prostate cancer: evaluation of patient outcomes and practice variation. Implement Sci. 2015;11:87.

Stapleton H. Qualitative study of evidence based leaflets in maternity care. BMJ. 2002;324:639.

Frosch D. Incorporating shared decision making into primary care in a preferred provider organizational model. In: Research & Implementation Report. Boston: Informed Medical Decisions Foundation; 2011. p. 38–43.

Sepucha K, Simmons L. Improving patient involvement in decision making in primary care. In: Research & Implementation Report. Boston: Informed Medical Decisions Foundation; 2011. p. 25–9.

Lewis CL. UNC Center for decision quality. In: Research & Implementation Report. Boston: Informed Medical Decisions Foundation; 2011. p. 53–9.

Acknowledgements

We thank Pamela Bagley for her support in developing the final electronic search strategy and for running the electronic database searches. Furthermore, we thank Robin Paradis Montibello for her work in the process of screening titles and abstracts.

Funding

Support for this research was provided by The Commonwealth Fund and the B. Braun Foundation. The views presented here are those of the authors and should not be attributed to The Commonwealth Fund or its directors, officers, or staff. The funding bodies were not involved in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IS, SK, and GE contributed to the conceptualization. IS, PH, SK, and GE contributed to the design. IS, AL, and PH carried out the data selection and extraction. IS, AL, SK, and GE contributed to the data analysis. IS and AL conducted the data synthesis. IS, SK, and GE were involved in the interpretation. SK and GE supervised the project. IS, GE and AL contributed to the visualization. IS and AL wrote the first manuscript draft. All authors were engage in reviewing and editing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

IS conducted one physician training in shared decision-making for which she received travel compensation from Mundipharma GmBH in 2015. AL and PH have no competing interests to declare. SK has no competing interests to declare and is an employee of the US government. GE reports personal fees from EMMI Solutions LLC, National Quality Forum, Washington State Health Department, PatientWisdom LLC, SciMentum LLC, Access Community Health Network, and Radcliffe Press outside the submitted work. GE has initiated and led the Option Grid TM patient decisions aids collaborative, which produces and publishes patient knowledge tools.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Protocol. (PDF 129 kb)

Additional file 2:

Electronic searches. (PDF 24 kb)

Additional file 3:

Gray literature search. (XLSX 15 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Scholl, I., LaRussa, A., Hahlweg, P. et al. Organizational- and system-level characteristics that influence implementation of shared decision-making and strategies to address them — a scoping review. Implementation Sci 13, 40 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-018-0731-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-018-0731-z