Abstract

Objective

The apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) is increasingly used as a quantitative biomarker in oncological imaging. ADC calculation is based on raw diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) data, and multiple post-processing methods (PPMs) have been proposed for this purpose. We investigated whether PPM has an impact on final ADC values.

Methods

Sixty-five lesions scanned with a standardized whole-body DWI-protocol at 3 T served as input data (EPI-DWI, b-values: 50, 400 and 800 s/mm2). Using exactly the same ROI coordinates, four different PPM (ADC_1–ADC_4) were executed to calculate corresponding ADC values, given as [10-3 mm2/s] of each lesion. Statistical analysis was performed to intra-individually compare ADC values stratified by PPM (Wilcoxon signed-rank tests: α = 1 %; descriptive statistics; relative difference/∆; coefficient of variation/CV).

Results

Stratified by PPM, mean ADCs ranged from 1.136–1.206 *10-3 mm2/s (∆ = 7.0 %). Variances between PPM were pronounced in the upper range of ADC values (maximum: 2.540–2.763 10-3 mm2/s, ∆ = 8 %). Pairwise comparisons identified significant differences between all PPM (P ≤ 0.003; mean CV = 7.2 %) and reached 0.137 *10-3 mm2/s within the 25th–75th percentile.

Conclusion

Altering the PPM had a significant impact on the ADC value. This should be considered if ADC values from different post-processing methods are compared in patient studies.

Key Points

• Post-processing methods significantly influenced ADC values.

• The mean coefficient of ADC variation due to PPM was 7.2 %.

• To achieve reproducible ADC values, standardization of post-processing is recommended.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) has become an indispensable tool for the examination of the central nervous system, and is increasingly used in body radiology. In proton MR imaging, extracellular water diffusion primarily contributes to measurable diffusivity. Further, capillary perfusion and molecular motion due to other causes, such as pressure or thermal gradients, also influence measured diffusivity values. As a consequence, quantitative results of DWI measurements are referred to as an apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) [1].

Typically, lower ADC values are observed in malignant tumours compared to healthy tissue [2, 3]. This is usually explained by microstructural differences, such as an increased cellularity in malignant tumours. Typical examples of false-positive cases are glandular structures in adenocarcinomas or colliquative necrosis [4, 5].

In clinical practice, the ADC is assessed using parametric maps. However, the generation of such maps is not straightforward. It requires post-processing of raw DWI data, and multiple post-processing methods (PPMs) have been published for this purpose. Notably, many ADC researchers have used software tools provided by the vendor. Such tools are frequently proprietary and thus details of the algorithms are not generally available to users [3, 6].

This calls into question the reproducibility of ADC values. Therefore, we aimed to investigate whether PPMs have an impact on the ADC value.

Methods

Patients

We chose 25 patients (mean age 58 years, range 37–81 years) randomly from our prospectively populated institutional PET-MRI database. The latter contains patients with various oncological diseases of advanced stages. Thus, histological verification, imaging follow-up and interdisciplinary tumour board consensus were defined as the standard of reference (SOR). Details on patient diagnosis are summarized in Table 1.

Such inclusion criteria were used in order to create a patient collective that would cover the whole spectrum of ADC values, ranging from about 0.2 (lymph nodes, bone marrow) to 2.4 * 10-3 mm2/s (kidney cortex [2, 7]).Footnote 1

Imaging

All patients were examined on a 3-Tesla Biograph mMR unit using phased array body coils (Siemens Healthcare Division, Erlangen, Germany). Patients thus received a whole-body (WB) examination at the Department of Radiology, University Hospital Erlangen, including morphological T1- and T2-weighted sequences and the DWI sequence.

The latter used WB, free-breathing, multiple-signal-acquisition EPI sequences (echo planar imaging) with three different b-values (50, 400 and 800 s/mm2). This DWI protocol followed recommendations for “Whole-Body Diffusion-weighted MR Imaging in Cancer” published by Padhani and colleagues in [3]. Technical details of this protocol are summarized in Table 2.

Post-processing methods (PPMs)

Four different PPMs were executed in every lesion, based on the same raw DWI data (i.e. the b50, b400 and b800 images). This approach allowed the creation of paired sets of ADC values to compare four PPMs on an intra-individual basis. The following PPMs were used:

-

ADC_1: ADC map generated automatically inline by the scanner using b-values of 50, 400 and 800 s/mm2 (Biograph mMR, Siemens Healthcare Division, Erlangen, Germany)

-

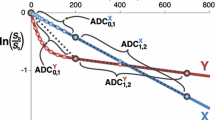

ADC_2: Manual logarithmic calculation [8]. ADC_2 was calculated using the signal intensity (SI) of raw DWI data at the given ROI position (see below): ADC_2 can thus be expressed as a function of SI at b50 and b800 as follows:

$$ ADC\_2=\frac{ln\frac{S{I}_{b800}}{S{I}_{b50}}}{b_{50}-{b}_{800}} $$(1) -

ADC_3: Manual ordinary least squares regression analysis [9]. ADC_3 is a function of SI at b50, b400 and b800 as follows:

$$ ADC\_3 = \frac{\left({b}_{50} - \overline{b}\right)*\left( \ln S{I}_{\mathrm{b}50} - \overline{ \ln SI}\right)+\left({b}_{400} - \overline{b}\right)*\left( \ln S{I}_{\mathrm{b}400} - \overline{ \ln SI}\right)+\left({b}_{800} - \overline{b}\right)*\left( \ln S{I}_{\mathrm{b}800} - \overline{ \ln SI}\right)}{{\left({b}_{50} - \overline{b}\right)}^2 + {\left({b}_{400} - \overline{b}\right)}^2+{\left({b}_{800} - \overline{b}\right)}^2} $$(2)Where \( \overline{b} \) equals the arithmetic mean of all three b-values (416.67 s/mm2) and \( \overline{\boldsymbol{SI}} \) equals the mean SI of all three b-values at the given ROI position.

-

ADC_4: Dedicated task card on post-processing workstation (MMWP: MultiModality Workplace, software version B19, Siemens Healthcare Division). According to prior exploratory analysis [10], noise reduction was set to a level of 10 (arbitrary units of pixel intensities), which generated a visual aspect similar to that of ADC_1.

The calculations of ADC_2 and ADC_3 were performed in Excel (v 15.16, Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA) on Mac OS 10 (Apple Inc., Cupertino, Ca). Further details on the ADC calculation are listed in the Supplementary Material section.

Assessment of lesions

DICOM files of raw DWI data and the two parametric ADC maps (ADC_1, ADC_4) were imported on a MMWP. Previous investigations have verified observer-related bias for the assessment of ADC values (CV from 6.8 to 7.9 [6]). As our study focused on the impact of PPMs on the ADC value, a single-read and single-reader approach was chosen to decrease such potential reader-dependent bias. First, lesions had to be identified based on the following criteria:

-

Definition: A lesion was defined as a malignant focus (primary, organ metastasis or lymphoma, c.f. Table 1). Lesions were identified on raw DWI data based on the SOR.

-

Lesion size: In order not to be biased by partial volume effects, a minimum lesion diameter of 1.5 cm was defined and the lesion had to be clearly visible in three consecutive slices on DWI images and ADC maps.

-

Multiple lesions per patient: If multiple lesions were present within one patient, only one lesion was included in every anatomic region (e.g. cervical, mediastinal, retroperitoneal lymph nodes (LN)). The maximum numbers of lesions assessed per patient was set to seven. This was done so as not to overload the study collective by data from patients at advanced disease stages.

Second, lesions were assessed by regions of interest (ROIs). The latter were defined according to the following criteria:

-

Positioning: One circular ROI was carefully positioned in order to encircle a representative area of the lesion with restricted diffusion.

-

Size: In order to minimize partial volume effects, the target ROI size was set to 1 cm2.

-

Transfer of ROI coordinates between PPMs: In previous works on the reproducibility of the ADC, ROI coordinates between different workstations were transferred manually [6, 11]. This approach is prone to a user-dependent bias. Our approach used user-independent software for this purpose (MMWP). It enables the automatic transfer of slice number, size and centre of the circular ROI between each PPM and the raw DWI data. Accordingly, user-dependent bias can be excluded and differences between ADC values of the PPM are related only to the underlying algorithms of the PPM.

This reading workflow is demonstrated on three clinical examples in Figs. 1, 2, and 3. Finally, the mean value of SI (raw DWI data) and the ADC (ADC_1 to ADC_4) of each lesion ROI was documented in a central Excel database.

Examples of reading approaches: A 55-year-old male with advanced-stage oesophageal cancer (arrow). The image shows the reading set-up, with raw diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) data on the top row (b50, b400, b800 [s/ mm2]), and, below, parametric apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps of ADC_1 and ADC_4. The latter were automatically generated inline by the scanner or by the viewing workstation (MMWP, details see above). On raw DWI data, the typical signal decay of free water can be depicted in the adjacent stomach, whereas the lesion itself shows signal alteration indicative of diffusion restriction (arrowhead). The corresponding ROI 1 was placed within the tumour in the b800 image and ROI coordinates were automatically transferred to all other remaining series. This approach excluded user-dependent bias when comparing the ROI statistics between the given series

A 59-year-old male with advanced-stage lung cancer and multiple cervical lymph node metastases. Set-up and automatic region of interest (ROI) transfer were the same as that in Fig. 1. A signal-to-noise (SNR) of 21.9 at b800 [s/mm2] was achieved in this small lesion that showed diffusion restriction as follows: apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values ranged from 0.453 (ADC_1) to 0.458 (ADC_4). Using the formulas (1) and (2) (see text), slightly higher values were calculated (ADC_2 = 0.459 and ADC_4 = 0.464)

A 47-year-old female diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Protocol was identical to that in Fig. 1. In this case, the corresponding region of interest (ROI) 1 (arrow) was placed within the tumour (noise ROI: arrowhead). Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values ranged from 1.800 (ADC_1) to 1.972 (ADC_2; ∆ = 9 %). Note the low remaining signal at b800 (signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of 3.5) in this heterogeneous lesion

Statistical methods

Data analysis followed a lesion-based approach and the independence of lesions in the same patient was assumed.

We evaluated the distribution of ADC values within each PPM (ADC_1 to ADC_4) and performed pairwise comparisons of the PPM (i.e. ADC_1 vs. ADC_2, ADC_1 vs. ADC_3, etc.).

Descriptive data analysis included arithmetic mean, relative difference (∆), median, SD (standard deviation), range (minimum to maximum), percentiles (5, 25, 75, 95) and the coefficient of variation (CV [%] = 100*SD/mean; [6, 11]).

ADC values were not normally distributed, as shown by the D’Agostino-Pearson test (P < 0.05), with differing means and medians, as well as visual analysis (box plots). Thus, pairwise comparison of the four PPMs was obtained using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (α = 1 %). P-values are given uncorrected, but results were interpreted considering potential alpha error.

Visual analysis was performed using box plots and Bland-Altman plots (BAPs). BAPs were used to check for systematic and proportional error between the four PPMs on the level of pairwise comparison. ∆PPM (PPM_1 minus PPM_2) was placed on the ordinate and PPM_1 on the abscissa. A regression line was placed into the point cloud of each BAP. If it the regression line could be fitted to the point cloud (criterion: slope, intercept: P < 0.05), the presence of a proportional error was assumed [12].

Statistical analyses were performed using MedCalc for Windows, version 12.5 (MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium).

Results

Mean ADC values of the PPMs ranged from 1.136 (ADC_1) to 1.206 (ADC_3; Table 3). This led to a relative ADC difference ∆ of up to 7.0 %.

With a ∆ = 8 %, dispersion of data was pronounced in the upper range of ADC values (Fig. 4). Thus, maximal values reached from 2.540 (ADC_1) to 2.763 (ADC_3). As shown in Fig. 4, comparable results were observed for the 95th percentiles (2.002: ADC_1 to 2.152: ADC_2). On the lower end of ADC, data were less scattered. Minimum values ranged from 0.312 (ADC_1) to 0.317 (ADC_4), with ∆ ≤ 1.6 %.

Box plots summarizing the distribution of apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values provided by the four different post-processing methods (PPMs). Median ranks between the PPMs showed significant differences (P ≤ 0.003). Note the different size of boxes and whiskers at the upper range of ADC values. In ADC_2, there were two outliers beyond the 97.5 quartile. One bone metastasis of lung cancer (ADC = 2.301) and one prostatic metastasis of a neuroendocrine tumour (ADC = 2.744) are shown. The latter caused all the outliers in the remaining PPMs

The pairwise comparison of ADC values revealed mean differences of ADC values ranging between −0.070 (ADC_1 vs. ADC_3) and 0.043 (ADC_3 vs. ADC_4; Table 4). On a case-by-case basis, such differences reached up to −0.866 (maximum difference for ADC_2 vs. ADC_4) or −0.137 in case of the 25th–75th percentile (ADC_1 vs. ADC_3).

Significant differences between all PPMs were noted (ADC_2 vs. ADC_3: P = 0,003, all other pairs: P < 0.001; c.f. Table 5). This led to a CV between 1.1 % (ADC_2 vs. ADC_3) and 10.4 % (ADC_1 vs. ADC_3). This gave a mean CV of 7.2 % (8.4 % if ADC_2 was not considered).

Visual analysis of BAP (Fig. 5) excluded the presence of systematic error. However, up to four outliers (ADC_1 vs. ADC_2, ADC_1 vs. ADC_3) were noted beyond the levels of agreement. Only one outlier was noted in two PPM pairs (ADC_1 vs. ADC_4 and ADC_2 vs. ADC_3).

Pairwise comparison of post-processing methods (PPMs) using Bland-Altman plots (BAPs). ∆PPM (PPM_1 minus PPM_2) is shown on the ordinate. PPM_1 is shown on the abscissa. Indicated are the limits of agreement, the mean relative difference, and the regression curve. Note the significant difference in mean ADC value in each pair as well as the presence of up to four outliers beyond the limits of agreement (+/- 1.96*SD: A and B). A proportional error was identified for E and F, with a slope of 0.12 and 0.13, respectively

A proportional error was identified in two PPM pairs (ADC_2 vs. ADC_4 and ADC_3 vs. ADC_4). Accordingly, differences between such pairs were significantly correlated (P < 0.05) with the magnitude of measurements. Namely, differences increased with rising ADC levels (slope = 0.12: ADC_2 vs. ADC_4; slope = 0.13: ADC_3 vs. ADC_4).

Discussion

DWI is an essential part of state-of-the-art oncological MR protocols. One reason for the unique success of DWI is certainly the seemingly easy way to interpret ADC maps. Concurring techniques – such as MR spectroscopy – require far more sophisticated post-processing, whereas ADC maps are usually generated fully automatically inline by the scanner.

In the literature, there are few clinical reports on the variability of the ADC. Essentially, there are three aspects that should be addressed in order to investigate the variability of the ADC:

First, ADC is influenced by the imaging protocol itself. Thus, many factors must be considered. Changing the echo time (TE), numbers of averages, spatial resolution or size of the field of view (FOV), etc., will have an impact on the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). The latter plays a key role in the generation of raw DWI data and has an important impact on ADC values [2, 13]. However, factors such as the scanner itself, sequence type, coils and vendors are also likely to have an impact on ADC values. Due to the number of influencing factors, it is difficult to express the effect of the imaging protocol itself on final ADC values in a simple number.

Corona-Villalobos et al. [11] performed serial measurements both of healthy tissue and a phantom using two different DWI sequences. The variability of corresponding ADC values were analyzed and quantified by a mean CV of 11 %. Donati et al. [14] compared ADC values of healthy volunteers within various regions of the abdomen. They used six different scanners sold by three different vendors at 1.5 and 3 Tesla field-strength. Those authors reported significant inter-vendor differences, with a minor effect of field strength. CV ranged from 7.0 % to 15.9 % if the liver ROIs were not considered. Of note, the CV of liver lesions was much higher (up to 27.1 %).

Second, identification of the ADC values depends on the radiologist her-/himself. This means that ADC assessment – although a quantitative measure by nature – is influenced by observer-related bias. This fact is due to inter- and intra-observer variability regarding manual ROI placement by the reader. A paper recently published by Clausner et al. [6] focused on this particular aspect of ADC analysis. The authors quantified this observer-related bias with a mean CV of 7.2 % (range 6.8–7.9 %). This value is in the range of ADC variability caused by the PPMs, according to our results (CV: 7.2).

Third, the PPMs of DWI data might have an impact on ADC values. Different from the first two, this fact has been largely ignored by the radiological community. Basic and computational scientists have developed a variety of different algorithms to calculate the ADC based on raw DWI data. All such approaches work slightly differently, and, thus, are likely to generate different numerical values. Of note, many software solutions being used in clinical, as well as scientific practice, are basically black boxes, as PPMs for DWI data are not generally available to the user. Based on an oncological dataset, we intra-individually compared ADC values of four different PPMs typically used for this purpose.

In our series, average ADC values did show a range of 7.0 %, providing values between 1.136 and 1.206. As these two extremes were calculated by the proprietary scanner software (ADC_1: the exact algorithm is not disclosed) and the ordinary least squares fit (ADC_3), results are indicative of further post-processing in the former. This could include fitting and smoothing algorithms, as well as the filtering of raw data. We did not aim to identify the best algorithm for the calculation of the ADC, yet, from a scientific perspective, the use of a black box tool should be discussed critically (ADC_1), particularly if the results differ significantly from an open-source tool such as that used for method ADC_3. However, average values showed not only significant differences between the two extremes, but also between all other methods (all pairwise comparisons: P ≤ 0.003).

One should question whether statistical significance really translates into clinical relevance. One approach to the interpretation of ADC maps in clinical practice is visual inspection. If such a qualitative analysis of ADC maps is the task, the choice of different post-processing algorithms certainly has a minor impact on final radiological assessment. However, if quantitative measurement is performed, the reader should be aware of this potential bias. This is becoming increasingly important, because a growing number of scientific papers suggest definitive ADC thresholds for differential diagnosis.

In a recent article, Baltzer et al. [15] proposed an ADC threshold of 1.4 to differentiate benign from malignant breast lesions. Data was supported by good specificity (80.5 %) and sensitivity (100 %), which was improved by integrating contrast-enhanced MRI (specificity 96.1 %, sensitivity 100 %). The authors used ADC maps that were automatically generated by the scanner software. Noise reduction level was set to an arbitrary level of 30 [15].

Similarly, the ADC was reported as a promising tool for differentiating focal liver lesions as benign or malignant. For example, ADC values under 1.470–1.600 were described as a potential sign of malignancy again with good, yet varying sensitivity (74–100 %) and specificity (77–100 %) [16–22]. Kim et al. [18] reported the use of a linear logarithmic regression. The other authors measured the ADC using ROIs on ADC maps.

Recently, DWI has become a popular tool for MR phenotyping of prostate lesions. Indeed, ADC could be used to predict Gleason grades, to stratify into further treatment groups (watchful waiting vs. therapeutic intervention), and to assess treatment response [23–25]. Again, methodological documentation within such papers on DWI post-processing is sparse, and the authors reported the use of only ADC maps that were generated by the scanner software [23–25].

Up to this point, we have discussed our results in the context of mean values provided by the four DWI PPMs. This approach averages out a number of details that are important for clinical practice. For example, mean values of ‘method A’ might be exactly the same as of ‘method B’. However, ‘method A’ might still produce different results on a pairwise comparison in certain cases. In fact, this is exactly what we observed in our data. Such details are of clinical importance and should be discussed.

As summarized in Table 3 and Fig. 4, variances between PPMs were pronounced in the upper range of ADC values (maximum: 2.540–2.763, ∆ = 8 %). The highest values were generated by ADC_2 (up to 2.744) and ADC_3 (up to 2.763). In comparison, the maximum ADC values generated by the proprietary algorithms were lower (ADC_1: 2.540, ADC_4: 2.599). However, dispersion of data was much smaller at the lower range of ADC values. Minimum values ranged from 0.312 (ADC_1) to 0.317 (ADC_4), giving a ∆ ≤ 1.6 %. Such a finding could be due to low SNR on the b800 images [2].

Differences were noted not only at the extremes, but also in terms of data distribution. This is reflected by a mean CV of 7.2 %. As shown in Table 4, differences also reached up to 0.137 in the 25th–75th percentile (ADC_1 vs. ADC_3). According to the point clouds of the BAP (Fig. 5, Table 5), proportional error could be identified between the ADC_4 and both open-source algorithms (ADC_2 and ADC_3; Fig. 5 E, F). Accordingly, the difference between such PPMs increased with the rising magnitude of ADC values.

Our results are of clinical importance. As the widespread clinical application of quantitative DWI is continuously increasing, academic MR radiologists are not the only group that should be aware of the impact of PPMs on ADC values. This effect might be relevant even within one single institution. For instance, if dedicated post-processing methods are used in addition to the standard ADC maps provided by the MR system, ADC metrics might be different. Therefore, we recommend the standardization of PPMs. This is of the utmost importance in longitudinal studies, for example, during follow-up of chemotherapy, in order to evaluate treatment response [3].

Limitations

In addition to the PPMs, in the present analysis, all other ‘confounding factors’ on ADC estimates were set constant. This approach was required to determine the exact effect of PPMs on ADC metrics. Accordingly, the results of our WB DWI study cannot be translated into other clinical scenarios literally. Such other ‘confounding factors’ are likely to further increase the variability of ADC-metrics in addition to the effect of PPMs. This is why they should be discussed briefly.

First, ADC metrics depend on the imaging protocol itself. It is well known that the protocol is not constant, but has to be optimized for the specific scenario. For instance, if a dedicated examination of the upper abdomen is required, parameters will necessarily differ from our protocol. For instance, more b-values will be chosen in this case [14], whereas a dedicated breast MRI [15] or even a WB DWI protocol will require different settings [3].

Yet, even in the given WB imaging scenario, different protocols coexist. Accordingly, some research teams favour the use of high b-values for this purpose, and skip low values below 200 for WB MRI [13]. In this scenario, the ADC value is, again, likely to be different from our data.

Future investigations should assess to what degree differences between PPMs are present, if DWI protocols are altered. Special attention should be paid to the comparison of ADC values derived only from the high-b-value signal intensities.

Second, there is no single way to document the results of ROI measurement. As the latter sums up the ADC values of every pixel within the given ROI, many metrics can be used for this purpose. These include minimum-ADC, maximum-ADC or histogram analysis. However, in clinical practice, the mean ADC value within the ROI is typically used [15]. This is why we chose this approach.

If the method of ROI analysis is changed, differences between the PPMs might also be altered. This is likely if a pixel-by-pixel comparison is performed between ADC metrics derived from various PPMs. As this approach is particularly capable of highlighting outlier values, it should be investigated in future studies.

Third, repeatability of DWI measurements is a limitation in itself. Thus, during serial measurements of a given pathology, ADC values will not be constant and will necessarily scatter. Even if all other ‘confounding factors’ – including the PPM itself – are set as constant, the repeatability ADC values will not be perfect. This effect has been reported by [11].

Certainly, such considerations limit the literal translation of our results into clinical practice. However, we did not aim to establish ‘the optimal PPM’. In fact, the aim of our study was to demonstrate that “PPM has an impact on ADC values”. Even if absolute differences between PPMs change due to altered study protocols, this key point will certainly hold true.

Conclusion

Post-processing of raw DWI data and calculation of the ADC is a delicate act and depends on the choice of the post-processing algorithms. We observed significantly different mean ADC values between all of the four algorithms tested, and demonstrated substantial intra-individual differences on a case-by-case basis, leading to a mean CV of 7.2 %. As the widespread clinical application of quantitative DWI is constantly increasing, MR radiologists should be aware of this phenomenon.

Notes

In the following parts of the manuscript, the unit of the ADC given as [10-3 mm2/s] will be omitted to improve legibility.

References

Schaefer PW, Grant PE, Gonzalez RG (2000) Diffusion-weighted MR imaging of the brain. Radiology 217:331–345

Dietrich O, Biffar A, Baur-Melnyk A, Reiser MF (2010) Technical aspects of MR diffusion imaging of the body. Eur J Radiol 76:314–322

Padhani AR, Koh D-M, Collins DJ (2011) Whole-body diffusion-weighted MR imaging in cancer: current status and research directions. Radiology 261:700–718

Malayeri AA, El Khouli RH, Zaheer A et al (2011) Principles and applications of diffusion-weighted imaging in cancer detection, staging, and treatment follow-up. Radiogr Rev Publ Radiol Soc N Am Inc 31:1773–1791

Qayyum A (2009) Diffusion-weighted imaging in the abdomen and pelvis: concepts and applications. Radiographics 29:1797–1810

Clauser P, Marcon M, Maieron M et al (2015) Is there a systematic bias of apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) measurements of the breast if measured on different workstations? An inter- and intra-reader agreement study. Eur Radiol. doi:10.1007/s00330-015-4051-2

Sumi M, Sakihama N, Sumi T et al (2003) Discrimination of metastatic cervical lymph nodes with diffusion-weighted MR imaging in patients with head and neck cancer. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 24:1627–1634

Le Bihan D, Breton E, Lallemand D, Grenier P, Cabanis E, Laval-Jeantet M (1986) MR imaging of intravoxel incoherent motions: application to diffusion and perfusion in neurologic disorders, Radiology 161:401–407

Schulze PM, Porath D (2012) Statistik: mit Datenanalyse und ökonometrischen Grundlagen, 7th ed. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, München

Zeilinger M, Lell M, Baltzer P, et al (2015) Einfluss der Rauschunterdrückung auf die Reproduzierbarkeit des Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (ADC). Fortschr Röntgenstr 187:WISS101_1. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1550779

Corona-Villalobos CP, Pan L, Halappa VG et al (2013) Agreement and reproducibility of apparent diffusion coefficient measurements of dual-b-value and multi-b-value diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging at 1.5 Tesla in phantom and in soft tissues of the abdomen. J Comput Assist Tomogr 37:46–51

Sardanelli F, Di Leo G (2009) Biostatistics for radiologists: planning, performing, and writing a radiologic study, 1st edn. Springer, Milan

Koh D-M, Blackledge M, Padhani AR et al (2012) Whole-body diffusion-weighted MRI: tips, tricks, and pitfalls. AJR Am J Roentgenol 199:252–262

Donati OF, Chong D, Nanz D et al (2014) Diffusion-weighted MR imaging of upper abdominal organs: field strength and intervendor variability of apparent diffusion coefficients. Radiology 270:454–463

Baltzer A, Dietzel M, Kaiser CG, Baltzer PA (2015) Combined reading of contrast enhanced and diffusion weighted magnetic resonance imaging by using a simple sum score. Eur Radiol. doi:10.1007/s00330-015-3886-x

Taouli B, Koh D-M (2010) Diffusion-weighted MR imaging of the liver. Radiology 254:47–66

Namimoto T, Yamashita Y, Sumi S et al (1997) Focal liver masses: characterization with diffusion-weighted echo-planar MR imaging. Radiology 204:739–744

Kim T, Murakami T, Takahashi S et al (1999) Diffusion-weighted single-shot echoplanar MR imaging for liver disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol 173:393–398

Taouli B, Vilgrain V, Dumont E et al (2003) Evaluation of liver diffusion isotropy and characterization of focal hepatic lesions with two single-shot echo-planar MR imaging sequences: prospective study in 66 patients. Radiology 226:71–78

Bruegel M, Holzapfel K, Gaa J et al (2008) Characterization of focal liver lesions by ADC measurements using a respiratory triggered diffusion-weighted single-shot echo-planar MR imaging technique. Eur Radiol 18:477–485

Gourtsoyianni S, Papanikolaou N, Yarmenitis S et al (2008) Respiratory gated diffusion-weighted imaging of the liver: value of apparent diffusion coefficient measurements in the differentiation between most commonly encountered benign and malignant focal liver lesions. Eur Radiol 18:486–492

Parikh T, Drew SJ, Lee VS et al (2008) Focal liver lesion detection and characterization with diffusion-weighted MR imaging: comparison with standard breath-hold T2-weighted imaging. Radiology 246:812–822

Bittencourt LK, Barentsz JO, de Miranda LCD, Gasparetto EL (2012) Prostate MRI: diffusion-weighted imaging at 1.5T correlates better with prostatectomy Gleason Grades than TRUS-guided biopsies in peripheral zone tumours. Eur Radiol 22:468–475

Hambrock T, Somford DM, Huisman HJ et al (2011) Relationship between apparent diffusion coefficients at 3.0-T MR imaging and Gleason grade in peripheral zone prostate cancer. Radiology 259:453–461

Kim TH, Jeong JY, Lee SW et al (2015) Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging for prediction of insignificant prostate cancer in potential candidates for active surveillance. Eur Radiol 25:1786–1792

Acknowledgments

Open access funding provided by Medical University of Vienna. Equipment support was provided by Siemens Healthcare Division, Erlangen, Germany. MZ, MU and ML have received technical support by Siemens Healthcare company, Erlangen, Germany. We thank Mary McAllister for valuable help in preparing the manuscript. The scientific guarantor of this publication is Dr. Matthias Dietzel and Dr. Martin Zeilinger. The authors of this manuscript declare no relationships with any companies, whose products or services may be related to the subject matter of the article. This study has material support by Siemens Healthcare division, Erlangen, Germany.Two of the authors (Dr. Matthias Dietzel, Prof. Pascal Baltzer) have significant statistical expertise. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects (patients) in this study.

Some study subjects or cohorts have been previously reported in:

1. Quick HH, von Gall C, Zeilinger M, et al. (2013) Integrated whole-body PET/MR hybrid imaging: clinical experience. Invest Radiol 48:280–289. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3182845a08

2. Wiesmüller M, Quick HH, Navalpakkam B, et al. (2013) Comparison of lesion detection and quantitation of tracer uptake between PET from a simultaneously acquiring whole-body PET/MR hybrid scanner and PET from PET/CT. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 40:12–21. doi: 10.1007/s00259-012-2249-y

Methodology: retrospective, cross sectional study, performed at one institution.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Martin Georg Zeilinger and Michael Lell contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Zeilinger, M.G., Lell, M., Baltzer, P.A.T. et al. Impact of post-processing methods on apparent diffusion coefficient values. Eur Radiol 27, 946–955 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-016-4403-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-016-4403-6