Abstract

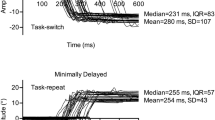

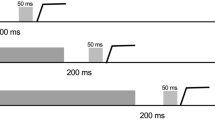

Alternating between different tasks represents an executive function essential to activities of daily living. In the oculomotor literature, reaction times (RT) for a ‘standard’ and stimulus-driven (SD) prosaccade (i.e., saccade to target at target onset) are increased when preceded by a ‘non-standard’ antisaccade (i.e., saccade mirror-symmetrical to target at target onset), whereas the converse switch does not elicit an RT cost. The prosaccade switch-cost has been attributed to lingering neural activity—or task-set inertia—related to the antisaccade executive demands of response suppression and vector inversion. It is, however, unclear whether response suppression and/or vector inversion contribute to the prosaccade switch-cost. Experiment 1 of the present work had participants alternate (i.e., AABB paradigm) between minimally delayed (MD) pro- and antisaccades. MD saccades require a response after target extinction and necessitate response suppression for both pro- and antisaccades—a paradigm providing a framework to determine whether vector inversion contributes to a task-set inertia. In Experiment 2, participants alternated between SD pro- and MD antisaccades—a paradigm designed to determine if a switch-cost is selectively imparted when a SD and standard response is preceded by a non-standard response. Experiment 1 showed that RTs for MD pro- and antisaccades were refractory to the preceding trial-type; that is, vector inversion did not engender a switch-cost. Experiment 2 indicated that RTs for SD prosaccades were increased when preceded by an MD antisaccade. Accordingly, response suppression engenders a task-set inertia but only for a subsequent stimulus-driven and standard response (i.e., SD prosaccade). Such a result is in line with the view that response suppression is a hallmark feature of executive function.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Allport DA, Styles EA, Hsieh S (1994) Shifting intentional set: exploring the dynamic control of tasks. In: Umiltà C, Moscovitch M (eds) Attention and performance 15: conscious and nonconscious information processing. The MIT Press, Cambridge, pp 421–452

Aponte EA, Stephan KE, Heinzle J (2019) Switch costs in inhibitory control and voluntary behaviour: a computational study of the antisaccade task. Eur J Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejn.14435

Barton JJ, Raoof M, Jameel O, Manoach DS (2006) Task-switching with antisaccades versus no-go trials: a comparison of inter-trial effects. Exp Brain Res 172:114–119

Becker W (1989) The neurobiology of saccadic eye movements. Metrics Rev Oculomot Res 3:13–67

Brainard DH (1997) The psychophysics toolbox. Spat Vis 10:433–436

Chan JL, DeSouza JF (2013) The effects of attentional load on saccadic task switching. Exp Brain Res 227:301–309

Cherkasova MV, Manoach DS, Intriligator JM, Barton JJ (2002) Antisaccades and task-switching: interactions in controlled processing. Exp Brain Res 144:528–537

Cornelissen F, Peters E, Palmer J (2002) The Eyelink Toolbox: Eye tracking with MATLAB and the Psychophysics Toolbox. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput 34:613–617

Dafoe JM, Armstrong IT, Munoz DP (2007) The influence of stimulus direction and eccentricity on pro- and anti-saccades in humans. Exp Brain Res 179:563–570

Derrfuss J, Brass M, Neumann J, von Cramon DY (2005) Involvement of the inferior frontal junction in cognitive control: meta-analyses of switching and Stroop studies. Hum Brain Mapp 25:22–34

DeSimone JC, Weiler J, Aber GS, Heath M (2014) The unidirectional prosaccade switch-cost: correct and error antisaccades differentially influence the planning times for subsequent prosaccades. Vis Res 96C:17–24

Everling S, Johnston K (2013) Control of the superior colliculus by the lateral prefrontal cortex. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 368:20130068

Fitts PM (1954) The information capacity of the human motor system in controlling the amplitude of movement. J Exp Psychol Gen 47:381–391

Gillen C, Heath M (2014) Target frequency influences antisaccade endpoint bias: evidence for perceptual averaging. Vis Res 105:151–158

Hallett PE (1978) Primary and secondary saccades to goals defined by instructions. Vis Res 8:1279–1296

Harris CM (1995) Does saccadic undershoot minimize saccadic flight-time? A Monte–Carlo study. Vis Res 35:691–701

Heath M, Bell J, Holroyd CB, Krigolson O (2012) Electroencephalographic evidence of vector inversion in antipointing. Exp Brain Res 221:19–26

Heath M, Hassall CD, MacLean S, Krigolson OE (2015) Event-related brain potentials during the visuomotor mental rotation task: the contingent negative variation scales to angle of rotation. Neuroscience 311:153–165

Heath M, Gillen C, Samani A (2016) Alternating between pro- and antisaccades: switch-costs manifest via decoupling the spatial relations between stimulus and response. Exp Brain Res 234:853–865

Heath M, Colino FL, Chan J, Krigolson OE (2018) Visuomotor mental rotation of a saccade: the contingent negative variation scales to the angle of rotation. Vis Res 143:82–88

Kleiner M, Brainard D, Pelli D, Ingling A, Murray R, Broussard C (2007) What's new in Psychtoolbox-3. Perception 36:1–16

Knox PC, Heming De-Allie E, Wolohan FDA (2018) Probing oculomotor inhibition with the minimally delayed oculomotor response task. Exp Brain Res 236:2867–2876

Lakens D (2017) Equivalence tests: a practical primer for t-tests, correlations, and meta-analyses. Soc Psychol Personal Sci 8:355–362

Li L, Wang M, Zhao QJ, Fogelson N (2012) Neural mechanisms underlying the cost of task switching: an ERP study. PLoS One 7:e42233

Manoach DS, Thakkar KN, Cain MS, Polli FE, Edelman JA, Fischl B, Barton JJ (2007) Neural activity is modulated by trial history: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study of the effects of a previous antisaccade. J Neurosci 27:1791–1798

Moon SY, Barton JJ, Mikulski S, Polli FE, Cain MS, Vangel M, Hämäläinen MS, Manoach DS (2007) Where left becomes right: a magnetoencephalographic study of sensorimotor transformation for antisaccades. Neuroimage 36:1313–1323

Munoz DP, Everling S (2004) Look away: the anti-saccade task and the voluntary control of eye movement. Nat Rev Neurosci 5:218–228

Perugini M, Gallucci M, Costantini G (2014) Safeguard power as a protection against imprecise power estimates. Perspect Psychol Sci 9:319–332

Pierrot-Deseilligny C, Rivaud S, Gaymard B, Müri R, Vermersch AI (1995) Cortical control of saccades. Ann Neurol 37:557–567

Pouget P, Logan GD, Palmeri TJ, Boucher L, Paré M, Schall JD (2011) Neural basis of adaptive response time adjustment during saccade countermanding. J Neurosci 31:12604–12612

Rogers RD, Monsell S (1995) Costs of a predictable switch between simple cognitive tasks. J Exp Psychol Gen 124:207–231

Tari B, Fadel MA, Heath M (2019) Response suppression produces a switch-cost for spatially compatible saccades. Exp Brain Res 237:1195–1203

Verbruggen F, Logan GD (2008) Response inhibition in the stop-signal paradigm. Trends Cogn Sci 12:418–424

Weiler J, Heath M (2012a) The prior-antisaccade effect influences the planning and online control of prosaccades. Exp Brain Res 216:545–552

Weiler J, Heath M (2012b) Task-switching in oculomotor control: unidirectional switch-cost when alternating between pro- and antisaccades. Neurosci Lett 530:150–154

Weiler J, Heath M (2014a) Oculomotor task switching: alternating from a nonstandard to a standard response yields the unidirectional prosaccade switch-cost. J Neurophysiol 112:2176–2184

Weiler J, Heath M (2014b) Repetitive antisaccade execution does not increase the unidirectional prosaccade switch-cost. Acta Psychol (Amst) 146:67–72

Weiler J, Hassall CD, Krigolson OE, Heath M (2015) The unidirectional prosaccade switch-cost: electroencephalographic evidence of task-set inertia in oculomotor control. Behav Brain Res 278:323–329

Wenban-Smith MG, Findlay JM (1991) Express saccades: is there a separate population in humans? Exp Brain Res 87:218–222

Wolohan FDA, Knox PC (2014) Oculomotor inhibitory control in express saccade makers. Exp Brain Res 232:3949–3963

Wurtz RH, Albano JE (1980) Visual-motor function of the primate superior colliculus. Annu Rev Neurosci 3:189–226

Wylie GR, Sumowski JF, Murray M (2011) Are there control processes, and (if so) can they be studied? Psychol Res 75:535–543

Yeung N, Nystrom LE, Aronson JA, Cohen JD (2006) Between-task competition and cognitive control in task switching. J Neurosci 26:1429–1438

Zhang M, Barash S (2000) Neuronal switching of sensorimotor transformations for antisaccades. Nature 408:971–975

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Discovery Grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada, and Faculty Scholar and Major Academic Development Fund Awards from the University of Western Ontario. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Melvyn A. Goodale.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tari, B., Heath, M. Pro- and antisaccade task-switching: response suppression—and not vector inversion—contributes to a task-set inertia. Exp Brain Res 237, 3475–3484 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-019-05686-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-019-05686-w