Abstract

Summary

An earlier systematic review on interventions to improve adherence and persistence was updated. Fifteen studies investigating the effectiveness of patient education, drug regimen, monitoring and supervision, and interdisciplinary collaboration as a single or multi-component intervention were appraised. Multicomponent interventions with active patient involvement were more effective.

Introduction

This study was conducted to update a systematic literature review on interventions to improve adherence to anti-osteoporosis medications.

Methods

A systematic literature review was carried out in Medline (using PubMed), Embase (using Ovid), Cochrane Library, Current Controlled Trials, ClinicalTrials.gov, NHS Centre for Review and Dissemination, CINHAL, and PsycINFO to search for original studies that assessed interventions to improve adherence (comprising initiation, implementation, and discontinuation) and persistence to anti-osteoporosis medications among patients with osteoporosis, published between July 2012 and December 2018. Quality of included studies was assessed.

Results

Of 585 studies initially identified, 15 studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria of which 12 were randomized controlled trials. Interventions were classified as (1) patient education (n = 9), (2) drug regimen (n = 3), (3) monitoring and supervision (n = 2), and (4) interdisciplinary collaboration (n = 1). In most subtypes of interventions, mixed results on adherence (and persistence) were found. Multicomponent interventions based on patient education and counseling were the most effective interventions when aiming to increase adherence and/or persistence to osteoporosis medications.

Conclusion

This updated review suggests that patient education, monitoring and supervision, change in drug regimen, and interdisciplinary collaboration have mixed results on medication adherence and persistence, with more positive effects for multicomponent interventions with active patient involvement. Compared with the previous review, a shift towards more patient involvement, counseling and shared decision-making, was seen, suggesting that individualized solutions, based on collaboration between the patient and the healthcare provider, are needed to improve adherence and persistence to osteoporosis medications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Osteoporosis remains a major health problem worldwide influencing patient’s health-related quality of life, mortality, and representing a substantial economic burden on society. The burden of osteoporosis is further expected to increase as a result of the aging population [1, 2]. Osteoporosis medications have shown to be effective in fracture risk reduction [3]; however, it is well known that adherence to osteoporosis medications is poor and suboptimal, varying from 34 to 75% in the first year of treatment [4, 5]. Persistence levels at 1 year were estimated between 18 and 75% [6]. This suboptimal adherence and persistence leads to increased fracture rate (up to 30%) and worse health outcomes (more subsequent fractures, lower quality of life, and higher mortality), substantially deteriorating the cost-effectiveness resulting from these medications [7, 8].

Improving adherence to osteoporosis medications is therefore needed but this remains a challenging task. Many factors of non-adherence and non-persistence to osteoporosis medications have been identified such as older age, polypharmacy, side effects, and lack of patient education. Reasons for non-adherence are thus numerous and multidimensional, varying for each patient [9]. Several interventions and programs have therefore been developed to improve osteoporosis medications adherence. A previous systematic literature review (SLR) published in 2012 noted several promising interventions to improve osteoporosis medication adherence and persistence, such as drug regimen and patient support, automatic electronic prescription, and pharmacist intervention [10]. This SLR, limited to articles published up to June 2012, further revealed a limited number of studies, the lack of rigorous evaluation of clinical effectiveness, and therefore the need for further studies [10].

Since this SLR, theories and practical experience on adherence and adherence interventions have evolved [11]. Moreover, the methodological quality of non-pharmacological interventions has overall improved. This, together with continuing low adherence to anti-osteoporosis medications [12], the frequent access to the previous SLR, and the publications of several new adherence interventions preceding this study, justifies an update [10].

For this updated review, it was aimed to appraise studies concerning interventions to improve adherence and persistence to medications for osteoporosis patients in primary of secondary care, published between July 2012 and December 2018.

Methods

This systematic review was executed in accordance with the PRISMA statement and with the use of a review protocol [13, 14]. The protocol for this systematic review was registered in PROSPERO (unique ID number: 97472, available on https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/).

Search strategy

With the help of an expert library specialist, a comprehensive systematic literature search was designed and performed in Medline (using PubMed), Embase (using Ovid), Cochrane Library, Current Controlled Trials, ClinicalTrials.gov, NHS Centre for Review and Dissemination, CINHAL, and PsycINFO. Reference list of identified articles were then manually searched, and forward reference searching was conducted in Web of Science. Detailed search strategies can be found in Appendix 1.

Selection criteria

Articles were included if they met the following eligibility criteria: (1) original study which assessed the effects of interventions aimed on improving adherence or persistence of osteoporosis medications, (2) publication date between July 1, 2012, and December 31, 2018 (the search was restricted to this period to provide an update of the previously published SLR [10]), and (3) available in English language. Conference proceedings were not included.

The selection of articles was performed in a standardized manner in a three-step process. First, duplicate records were deleted. Second, articles were analyzed by screening the title and abstract (DC). In case of doubt, the article was included for full-text review. Third, full texts were independently reviewed on the eligibility criteria by two authors (DC and SdK). If necessary, consensus was reached by both authors through discussion with a third author (MH).

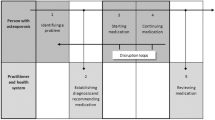

Definitions of adherence and persistence

Adherence and persistence to medications have been defined differently in several ways [15]. For organizing data for this review, the following ABC taxonomy, according to Vrijens et al., was followed [16]. Medication adherence consists of the three following quantifiable phases: (A) initiation (when the patient takes the first dose of a prescribed medication), (B) implementation (the extent to which a patient’s actual dosing corresponds to the prescribed dosing regimen, from initiation until the last dose), and (C) discontinuation (when the patient stops taking the prescribed medication, for whatever reason(s)). Persistence is defined as the length of time between initiation and the last dose, which immediately precedes discontinuation [16].

Extracted information

Data from the included studies were independently extracted by two authors (DC and SdK) in a predesigned data abstraction sheet. A third author (LS) checked independently all extracted data. General information including author, year of publication, country, and setting (primary care, secondary care, or other) were first collected, then the intervention specialist (GP, medical specialist, pharmacist, or other), type of study, population, sample size, outcome measurements (adherence or persistence), type of intervention, and follow-up time.

Type of interventions

Interventions extracted from data were classified into four categories based on previous studies [10, 12]: (1) patient education (provision of information), (2) drug regimen, (3) monitoring and supervision, and (4) interdisciplinary collaboration. These interventions were frequently combined with patient counseling (advice and debate on provided information focused on the individual patient). These modalities could be administered as a single- or multicomponent intervention. In this review, a multicomponent intervention halters two different types of components, e.g., provision of educational material and patient counseling, whereas a single component solely uses one intervention.

Study quality

Risk of bias of the included studies was assessed by two researchers (DC and SdK) with the Revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2) or the Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies - of Interventions (ROBINS-I) assessment tool [17, 18]. To assess study quality, different quality appraisal tools were used specifically designed for each type of study. For observational studies, the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) tool [19] was used. For clinical trials, the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) tool [20] was used. Two researchers (DC and VW) independently evaluated the selected studies. A third researcher (LS) randomly checked four appraisals as additional check. All differences were resolved by consensus through discussion.

Synthesis of results

Due to the expected heterogeneity in the methods of adherence measurement and of study outcomes, the analysis was focused on a qualitative assessment, and no meta-analysis was conducted.

Results

Literature search

After deletion of duplicate records, our search resulted in 585 articles, of which 55 passed the abstract and title screening (Fig. 1). After full-text assessment, 40 articles were excluded because of the following reasons: no full text available (n = 8), not specific for osteoporosis patients (n = 1), review article (n = 2), lack of a medication adherence intervention (n = 22), conference proceedings (n = 4), published before July 1, 2012 (n = 2), and methodologic article (n = 1), resulting in 15 articles. The PRISMA flow chart is presented in Fig. 1.

Study characteristics

The main study characteristics can be found in Table 1. Twelve studies were randomized controlled trials (RCT) [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31] of which one was a cross-over RCT design [32]. Other studies were non-randomized, uncontrolled studies [33,34,35]. A total of 162,804 patients were included, 155,803 in the intervention group and 7001 control patient [30, 35]. There was a large difference in sample sizes varying from 79 to 147,071 [28, 35]. Ninety-five percent of patients came from two studies [24, 35]. The majority of patients were female, and eight studies included solely females [22, 25,26,27,28, 30, 32]. Seven studies were European [22, 26, 27, 30,31,32,33], five studies North-American [24, 25, 29, 34, 35], two from Australia [21, 28], and one from Japan [23]. Follow-up time varied from 6 to 24 months [21, 28]. Interventions were executed in secondary care (n = 13) [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32, 34, 35], primary care (n = 1) [33], or in both primary and secondary care (n = 1) [21]. Seven of the 15 interventions were conducted by either physicians and/or nurses/nurse practitioners (n = 7) [21, 24, 26,27,28, 31, 34]. Other interventions were conducted by trained coordinators (n = 1) [35], medical secretaries (n = 1) [22], pharmacists (n = 1) [33], or a combination of physicians and allied healthcare workers (n = 1) [36]. Four studies did not report by whom the intervention was conducted [23, 25, 30, 32].

The studied interventions, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and summarized outcomes can be found in Tables 2 and 3.

Definition and measures

Measures of adherence

Adherence to prescribed medication was mentioned as an outcome in fourteen studies [21,22,23,24,25, 27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. Adherence was reported as initiation (n = 1), implementation (n = 9), and discontinuation (n = 4). In two studies, the type of adherence was not described [23, 24]. Initiation was described as initiation of osteoporosis treatment by primary care physician 12 months after a fragility fracture [29]. Implementation was described as medication possession rate (MPR) ≥ 80% [21, 22, 28, 33, 35], a medication possession rate (MPR) ≥ 50% [32, 35], per the instructions of the physician at regular intervals and dosages [30], the percentage of the prescribed dose taken [27], scoring ≥ 75% on the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS) [31], self-report of current osteoporosis medication use at 6 months [25], or active treatment 12 months after initiation [34]. Discontinuation was described as continuing to receive treatment over the long term [30], as permanently stopping anti-osteoporosis medication [33], continuation of treatment after 26 weeks [32], or continuing of medication after 1 year [22]. Persistence was mentioned as an outcome in three studies [26, 27, 31]. It was described as taking medication 10 out of 12 months without medication gaps longer than 2 weeks [27]. Two studies did not describe persistence [26, 31]. In six studies [21, 23, 25, 26, 31, 32], the effect of a single-component intervention was studied, while nine studies [22, 24, 27,28,29,30, 33,34,35] studied a multicomponent intervention.

Questionnaires and/or diaries (n = 8) [22, 23, 25, 27,28,29,30,31], and pharmacist databases (n = 3) [21, 26, 33] were the most common sources methods for data collection. Other methods included patient records (n = 1) [35], empty drug boxes (n = 1) [27], laboratory tests (n = 1) [26], collection of medication during a consultation (n = 1) [32], and retrieved from the PAADRN trial (n = 1) [24, 37]. In one study, the authors did not report the method of data collection [34].

Patient education

Nine studies assessed the effects of patient education of which were seven RCTs, one cohort study, and one observational study [24, 25, 27,28,29,30,31, 34, 35]. In these nine studies, adherence was used as an outcome [24, 25, 27,28,29,30,31, 34, 35], and in two studies, persistence was also reported [27, 31]. Interventions can further be classified into educational sessions (consisted of meetings with 4–6 patients and a psychologist) (n = 2) [27, 30], provision of educational material (n = 8) [24, 25, 27, 29,30,31, 34, 35], and the use of a decision aid (n = 1) [28]. Educational material varied between providing information booklets or flyers [24, 25, 27, 29,30,31, 34], providing DVDs with visual information regarding the intervention, (treatment of) osteoporosis, and how to discuss this with the physician [25], or a decision aid which included the personal risk on a fracture [28]. In seven studies, education was combined with counseling. The way and the intensity of patient counseling varied from offering patients advice and recommendation concerning the educational material [35] to up to four telephonic follow-up calls combined with 4 group sessions in 12 months [30].

A significant effect on medication adherence was observed in two of the nine studies, both multicomponent interventions [29, 34]. One study combining patient education, counseling, blood tests, BMD test prescription, and follow-up phone calls resulted in an increase in adherence between 40 and 53% in the intervention groups, compared with 19% in usual care and odds ratios of 2.55–5.07 [29]. When an educational program was combined with a referral to an endocrinologist for a consultation, implementation rates improved significantly compared with usual care (for females, intervention 95% vs. control 90%; for males, intervention 97% vs. control 82%; both p = 0.04) [34]. Seven studies were unable to significantly affect adherence to osteoporosis medications or provide a significance level with their results [24, 25, 27, 28, 30, 31, 35]. Albeit, of these studies, the single-component interventions included solely providing educational material [25, 31]. The multicomponent interventions included providing patients the DXA score combined with educational material [24], identification of patients at risk for osteoporosis combined with educational material [35] providing a decision aid or FRAX results combined with patient counseling [28], and the more extensive provision of educational material, an alarm clock, phone calls, and patient counseling/group meetings [27, 30]. In none of the included studies, a significantly positive effect on persistence was described.

Drug regimen

Three studies evaluated the effect of alterations in drug regimen compared with usual care. Of these studies, two were RCTs and one was an observational study [23, 32, 33]. Adherence (not further defined) was the primary outcome in one study [23], while the two other studies focused on both implementation and discontinuation [32, 33]. The studies concerned single-component interventions as either offering patients a choice of flexible dosing regimen [32] or switching to an alternative drug with longer dosing intervals [23], or multicomponent interventions of a combination of signaling of non-adherence, and offering alternative medication combined with counseling [33]. None of the studies resulted in a significant improvement of adherence/implementation. There was a significant positive effect on discontinuation in two studies. In one study, a choice of flexible dosing regimen compared with usual care resulted in 86% vs. 79% no discontinuation (p = 0.03) [32], and the combination of signaling of non-adherence with offering alternative medication combined with counseling compared with usual care led to no discontinuation 84% vs. 72% (p < 0.01) [33].

Monitoring and supervision

Monitoring and supervision was investigated in two RCT studies [22, 26]. Implementation and discontinuation to osteoporosis medications were the outcome in one study [22] and persistence in the other [26]. In both studies, patients frequently received telephone calls as a reminder to take their medication as prescribed, compared with usual care. In one study, this was a multicomponent intervention, where the phone calls were combined with patient counseling [22]. There was a positive effect on both implementation and discontinuation in one study with increased implementation rates of 65% vs. 33% (p < 0.01) and non-discontinuation rates of 73% vs. 51% (p < 0.01) in the intervention group [22]. Persistence was not significantly affected [26].

Interdisciplinary collaboration

Finally, the influence of setting of care was assessed in one RCT study, with longer term implementation of osteoporosis medications as outcome [21]. During this single-component study [21], patients, in whom anti-osteoporosis medication was initiated at the Fracture Liaison Service (FLS), were either allocated after 3 months to further follow up in the FLS (usual care) or transferred to the principal care provider (PCP). After 24 months, there was no difference between the groups in terms of implementation of anti-osteoporosis medications.

Quality assessment

The risk of bias was assessed with the RoB 2 or ROBINS-I tool [17, 18]. The overall risk of bias of the included studies varied from low to high/serious, increased risk of bias concerned missing outcome data and selection of participants. The results are presented in Appendix 2.

The quality of the three observational studies and twelve RCTs was assessed with the STROBE tool [19] and with the CONSORT tool [38], respectively. Overall, the quality of the studies was variable and moderate. The results are presented in Appendix 3. In general, the setting, eligibility criteria, and the rationale were described well in the observational studies [33,34,35]. However, sensitivity analysis, handling of missing data, and the sample size calculation were absent in all three studies. The sources of data for each variable fully were only described in one study [35]. The RCTs were sufficient when considering abstracts, eligibility criteria of the participants, and the statistical analysis. One study reported changes which occurred after the trial commenced [28]. None of the studies reported any harms and methods of randomization, and allocations were poorly described. Sources of funding were not reported in one study [31]. In none of the studies, the interventions or data were blinded for the patient, physician, or analyst.

There was no evident difference regarding the risk of bias or study quality, when considering the different types of interventions or between single or multicomponent interventions.

Discussion

For this updated review, 15 studies and 19 comparisons in which interventions to improve adherence and persistence to osteoporosis medications were assessed. Interventions included patient education, monitoring and supervision, change in drug regimen combined with patient support, and interdisciplinary collaboration.

Different approaches for patient education (combined with counseling) were the most studied interventions, but the effect on adherence was limited. Only two out of nine studies reported significant improvements on implementation and discontinuation [29, 34], and none of the interventions reported a positive effect on persistence. Change in drug regimen, combined with patient support [23, 32, 33], did not result in a positive effect on implementation. Furthermore, a significantly positive effect on discontinuation to osteoporosis medications was sorted when patients were offered a choice of flexible dosing regime and a combination of signaling of non-adherence with offering alternative medication combined with counseling. There was a notable difference in patient participation and involvement; if the patient was counseled or offered participation in the choice regarding the decision concerning drug regimen, there was an improvement in no discontinuation [32, 33], in contrast to no improvement in adherence when the patient was not involved [23]. This implicates that patient involvement is an important factor to improve medication persistence while employing flexible dosing regimen. Also, since there was no effect on implementation, but an effect on discontinuation, it seems change in drug regimen is only useful for patients already using osteoporosis medications. Monitoring and supervision were shown to have a positive effect on both implementation and discontinuation, but only in one study. In this study, patients were offered counseling, and not solely monitored or supervised [22]. Finally, there was no difference in terms of persistence to osteoporosis medications when patients were either allocated to the regular FLS for 24 months (usual care) or transferred to the principal care provider (PCP) after 3 months for a follow-up of 21 months [21]. Although this did not lead to an improvement in medication persistence, it also did not lead to a decrease. This implicates that the role of the rheumatologist can partially be replaced by other physicians making the treatment more flexible.

Compared with the previous SLR, there was a notable difference in interventions; in the included articles for this review, there was more emphasis on patient involvement, counseling, and shared decision-making, hence multicomponent interventions, instead of solely patient information/education or supervision each (single component intervention), and there was a larger variation of healthcare professionals involved in conduction of these interventions. Earlier studies described that patient education had the potential to increase adherence, but new research published since the previous SLR could not confirm this, despite some reasonable effect size, and the effect of solely patient education seems limited [39,40,41]. Improvement is only expected when it is combined with counseling. Similarities are found when comparing strategies in other chronic diseases, as diabetes; education is seen as the cornerstone which is integrated in each intervention strategy combined with involvement of the healthcare provider and patient, a so-called combined educational-behavioral strategy [42]. Compared with the previous SLR, an improvement in the quality of studies is observed. Of the fifteen included studies, the majority were randomized controlled trials, mostly of reasonable quality. However, there was heterogeneity in methodology and (reporting of) results, similar to the previous SLR. Risk of bias was variable, from low to high/serious. As in the previous SLR, almost all studies used adherence as outcome, and persistence was less frequently used. The definitions which were used for adherence and persistence still varied greatly; for instance, we found twelve different descriptions of adherence. These findings show that the taxonomy for describing and defining adherence to medications by Vrijens et al. is not fully implemented yet [16], as was also concluded in the previous SLR.

There was an effect of a change in drug regimen, as reported in earlier studies, in which flexible dosing regimens were effective in increasing adherence, regardless of the level of patient involvement [10]. However, multicomponent interventions, where a change of drug regimen is combined with counseling, also led to an increase of no discontinuation levels. In the field of neurology, especially migraine/chronic headache, it is emphasized that drug regimens concerning preventive medication should be tailored to lifestyle, to increase adherence, thus also focusing on multicomponent intervention [43].

Interdisciplinary collaboration was described successful when improving adherence in other studies within the field of osteoporosis or in other diseases [44, 45], contrary to our findings. However, to lift the burden on medical specialists, interdisciplinary collaboration could be of added value, since there was no decrease of persistence either [46,47,48].

The currently available data on adherence and persistence to osteoporosis medications have several limitations. First, the available data was mostly self-reported, introducing social desirability and recall bias, or may not be true values due to the use of prescription data and time until last prescription refill [6]. In addition, this resulted also in an increased risk of bias of missing outcome data.

Second, in none of the studies, the intervention or data were blinded for the patient, physician, or analyst. While this is not always possible, especially for patients, it could result in confirmation bias and selection bias. Third, the follow-up time was limited to a maximum of 24 months; hence, osteoporosis is a chronic disease; this could be of influence on the long-term results of adherence and persistence.

There were strengths and potential issues in relation to the methodology and execution of this review. The search was designed with the help of an expert library specialist. Article selection, data extraction, and quality appraisal were conducted by at least two researchers. Furthermore, the review was executed in accordance with the PRISMA statement. Although we found 15 new adherence intervention studies, the conclusions on adherence interventions remain blurred, and still no clear recommendations regarding interventions to improve medication adherence and persistence can be derived from our review. Moreover, we recognized the same limitations with regard to quality and thus interpretation, comparison, or meta-analyses. In other words, we confirmed variability in definition and measurement of adherence outcome, challenges to classify adherence interventions, and limitations in design related to blinding of patients and/or physicians, sensitivity analysis, handling of missing data, and often sample calculations. Notwithstanding, we feel our review does provide added value by pointing to the direction on which future research should focus, namely, multicomponent interventions with active patient involvement.

With regard to the classification of interventions into four categories, non-homogenous groups are possibly not comparable with other studies/reviews. The ABC taxonomy by Vrijens et al. [16] was used for organizing and comparing data for this review, resulting in the use of the terms adherence, subdivided in initiation, implementation and discontinuation, and persistence, which sometimes differed compared with the terms used in the original articles. Also, the influence of the health system (e.g., co-payments, reimbursement, and difference in primary and secondary care), which differs per country, was not considered [9]. In a recent ESCEO paper, different recommendations to improve medication adherence and persistence were drafted by an international working group [12]. These include patient education and counseling, improving patient interaction and shared-decision making, and dose simplification such as the use of gastro-resistant risedronate tablets that could be taken after breakfast. In addition, the ESCEO working group recognized the need for more evidence and high-quality research and provides recommendations for further research in the field.

In conclusion, this updated review suggests that improving adherence and persistence to osteoporosis medications remains a complex and challenging issue, and no clear recommendations can unfortunately be derived from it. Patient education, monitoring and supervision, change in drug regimen combined with patient support, and interdisciplinary collaboration were shown to have some effect on either adherence or persistence but only in some of the studies. However, interestingly, multicomponent interventions with active patient involvement were the most effective interventions when aiming to increase adherence and/or persistence to osteoporosis medications. It would thus be important to design appropriate multicomponent interventions and to critically evaluate them with means of well-designed randomized controlled trials, ideally with longer follow-up.

References

Hernlund E, Svedbom A, Ivergård M et al (2013) Osteoporosis in the European Union: medical management, epidemiology and economic burden: a report prepared in collaboration with the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) and the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industry Associations (EFPIA). Arch Osteoporos 8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-013-0136-1

Lötters FJB, van den Bergh JP, de Vries F et al (2016) Current and future incidence and costs of osteoporosis-related fractures in the Netherlands: combining claims data with BMD measurements. Calcif Tissue Int 98:235–243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-015-0089-z

Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Johansson H et al (2013) European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 24:23–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-012-2074-y

Klop C, Welsing PMJ, Elders PJM, Overbeek JA, Souverein PC, Burden AM, van Onzenoort H, Leufkens HG, Bijlsma JW, de Vries F (2015) Long-term persistence with anti-osteoporosis drugs after fracture. Osteoporos Int 26:1831–1840. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-015-3084-3

Netelenbos JC, Geusens PP, Ypma G, Buijs SJ (2011) Adherence and profile of non-persistence in patients treated for osteoporosis-a large-scale, long-term retrospective study in the Netherlands. Osteoporos Int 22:1537–1546. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-010-1372-5

Fatoye F, Smith P, Gebrye T, Yeowell G (2019) Real-world persistence and adherence with oral bisphosphonates for osteoporosis: a systematic review. BMJ Open 9:e027049. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027049

Hiligsmann M, Rabenda V, Gathon HJ et al (2010) Potential clinical and economic impact of nonadherence with osteoporosis medications. Calcif Tissue Int 86:202–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-009-9329-4

Ross S, Samuels E, Gairy K et al (2011) A meta-analysis of osteoporotic fracture risk with medication nonadherence. Value Heal 14:571–581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2010.11.010

Yeam CT, Chia S, Tan HCC, Kwan YH, Fong W, Seng JJB (2018) A systematic review of factors affecting medication adherence among patients with osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 29:2623–2637. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-018-4759-3

Hiligsmann M, Salas M, Hughes DA et al (2013) Interventions to improve osteoporosis medication adherence and persistence: a systematic review and literature appraisal by the ISPOR Medication Adherence & Persistence Special Interest Group. Osteoporos Int 24:2907–2918. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-013-2364-z

Kini V, Ho PM (2018) Interventions to improve medication adherence: a review. JAMA 320:2461–2473. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.19271

Hiligsmann M, Cornelissen D, Vrijens B et al (2019) Determinants, consequences and potential solutions to poor adherence to anti-osteoporosis treatment: results of an expert group meeting organized by the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal. Osteoporos Int:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-019-05104-5

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J et al (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol 62:1–34. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2700

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Lehane E, McCarthy G (2009) Medication non-adherence—exploring the conceptual mire. Int J Nurs Pract 15:25–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-172X.2008.01722.x

Vrijens B, De Geest S, Hughes DA et al (2012) A new taxonomy for describing and defining adherence to medications. Br J Clin Pharmacol 73:691–705. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04167.x

Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ et al (2019) RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ Published Online First. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4898

Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC et al (2016) ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ Published Online First. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i4919

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M et al (2014) The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg 12:1495–1499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.07.013

Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D (2010) CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 340:698–702. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c332

Ganda K, Schaffer A, Pearson S, Seibel MJ (2014) Compliance and persistence to oral bisphosphonate therapy following initiation within a secondary fracture prevention program: a randomised controlled trial of specialist vs. non-specialist management. Osteoporos Int 25:1345–1355. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-013-2610-4

Ducoulombier V, Luraschi H, Forzy G et al (2015) Contribution of phone follow-up to improved adherence to oral osteoporosis treatment. Am J Pharm Benefits 7:e81–e89 https://ajmc.s3.amazonaws.com/_media/_pdf/AJPB_0506_2015_Ducoulombier(final).pdf

Tamechika S-Y, Sasaki K, Hayami Y et al (2018) Patient satisfaction and efficacy of switching from weekly bisphosphonates to monthly minodronate for treatment and prevention of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis in Japanese patients with systemic rheumatic diseases: a randomized, clinical trial. Arch Osteoporos 13:67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-018-0451-7

Cram P, Wolinsky FD, Lou Y, Edmonds SW, Hall SF, Roblin DW, Wright NC, Jones MP, Saag KG, PAADRN Investigators (2016) Patient-activation and guideline-concordant pharmacological treatment after bone density testing: the PAADRN randomized controlled trial. Osteoporos Int 27:3513–3524. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-016-3681-9

Danila MI, Outman RC, Rahn EJ, Mudano AS, Redden DT, Li P, Allison JJ, Anderson FA, Wyman A, Greenspan SL, LaCroix A, Nieves JW, Silverman SL, Siris ES, Watts NB, Miller MJ, Curtis JR, Warriner AH, Wright NC, Saag KG (2018) Evaluation of a multimodal, direct-to-patient educational intervention targeting barriers to osteoporosis care: a randomized clinical trial. J Bone Miner Res 33:763–772. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.3425

van den Berg P, van Haard PMM, van der Veer E et al (2018) A dedicated fracture liaison service telephone program and use of bone turnover markers for evaluating 1-year persistence with oral bisphosphonates. Osteoporos Int 29:813–824. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-017-4340-5

Bianchi ML, Duca P, Vai S, Guglielmi G, Viti R, Battista C, Scillitani A, Muscarella S, Luisetto G, Camozzi V, Nuti R, Caffarelli C, Gonnelli S, Albanese C, de Tullio V, Isaia G, D'Amelio P, Broggi F, Croci M (2015) Improving adherence to and persistence with oral therapy of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 26:1629–1638. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-015-3038-9

LeBlanc A, Wang AT, Wyatt K, Branda ME, Shah ND, van Houten H, Pencille L, Wermers R, Montori VM (2015) Encounter decision aid vs. clinical decision support or usual care to support patient-centered treatment decisions in osteoporosis: the osteoporosis choice randomized trial II. PLoS One 10:e0128063. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0128063

Roux S, Beaulieu M, Beaulieu MC, Cabana F, Boire G (2013) Priming primary care physicians to treat osteoporosis after a fragility fracture: an integrated multidisciplinary approach. J Rheumatol 40:703–711. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.120908

Tüzün Ş, Akyüz G, Eskiyurt N, Memiş A, Kuran B, İçağasıoğlu A, Sarpel T, Özdemir F, Özgirgin N, Günaydın R, Cakçı A, Yurtkuran M (2013) Impact of the training on the compliance and persistence of weekly bisphosphonate treatment in postmenopausal osteoporosis: a randomized controlled study. Int J Med Sci 10:1880–1887. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijms.5359

Gonnelli S, Caffarelli C, Rossi S, di Munno O, Malavolta N, Isaia G, Muratore M, D'Avola G, Gatto S, Minisola G, Nuti R (2016) How the knowledge of fracture risk might influence adherence to oral therapy of osteoporosis in Italy: the ADEOST study. Aging Clin Exp Res 28:459–468. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-016-0538-1

Oral A, Lorenc R (2015) Compliance, persistence, and preference outcomes of postmenopausal osteoporotic women receiving a flexible or fixed regimen of daily risedronate: a multicenter, prospective, parallel group study. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 49:67–74

Stuurman-Bieze AGG, Hiddink EG, Van Boven JFM (2014) Proactive pharmaceutical care interventions decrease patients’ nonadherence to osteoporosis medication. Osteoporos Int 25:1807–1812. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-014-2659-8

Seuffert P, Sagebien CA, McDonnell M (2016) Evaluation of osteoporosis risk and initiation of a nurse practitioner intervention program in an orthopedic practice. Arch Osteoporos 11:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-016-0262-7

Beaton DE, Mamdani M, Zheng H, Jaglal S, Cadarette SM, Bogoch ER, Sale JEM, Sujic R, Jain R, Ontario Osteoporosis Strategy Fracture Clinic Screening Program Evaluation Team (2017) Improvements in osteoporosis testing and care are found following the wide scale implementation of the Ontario Fracture Clinic Screening Program: an interrupted time series analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 96:e9012. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000009012

Roux C, Hofbauer LC, Ho PR, Wark JD, Zillikens MC, Fahrleitner-Pammer A, Hawkins F, Micaelo M, Minisola S, Papaioannou N, Stone M, Ferreira I, Siddhanti S, Wagman RB, Brown JP (2014) Denosumab compared with risedronate in postmenopausal women suboptimally adherent to alendronate therapy: efficacy and safety results from a randomized open-label study. Bone 58:48–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2013.10.006

Edmonds SW, Wolinsky FD, Christensen AJ et al (2013) The PAADRN study: a design for a randomized controlled practical clinical trial to improve bone health. Contemp Clin Trials 34:90–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2012.10.002

Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, et al. (2013) CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials of TO. Ann Intern Med 1996

Jensen AL, Lomborg K, Wind G et al (2014) Effectiveness and characteristics of multifaceted osteoporosis group education-a systematic review. Osteoporos Int 25:1209–1224. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-013-2573-5

Solomon DH, Iversen MD, Avorn J et al (2012) Osteoporosis telephonic intervention to improve medication regimen adherence: a large, pragmatic, randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 172:477–483. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1977

Morfeld J-C, Vennedey V, Müller D, Pieper D, Stock S (2017) Patient education in osteoporosis prevention: a systematic review focusing on methodological quality of randomised controlled trials. Osteoporos Int 28:1779–1803. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-017-3946-y

Presley B, Groot W, Pavlova M (2018) Pharmacy-led interventions to improve medication adherence among adults with diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Res Soc Adm Pharm:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2018.09.021

Seng EK, Rains JA, Nicholson RA, Lipton RB (2015) Improving medication adherence in migraine treatment. Curr Pain Headache Rep 19:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-015-0498-8

Bowers BL, Drew AM, Verry C (2018) Impact of pharmacist-physician collaboration on osteoporosis treatment rates. Ann Pharmacother 52:876–883. https://doi.org/10.1177/1060028018770622

Jameson JP, Baty PJ (2010) Pharmacist collaborative management of poorly controlled diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Manag Care

Chow S (2017) Nurse practitioner fracture liaison role: a concept analysis. Orthop Nurs 36:385–391. https://doi.org/10.1097/NOR.0000000000000399

Toh LS, Lai PSM, Othman S, Wong KT, Low BY, Anderson C (2017) An analysis of inter-professional collaboration in osteoporosis screening at a primary care level using the D’Amour model. Res Soc Adm Pharm 13:1142–1150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2016.10.004

Tan ECK, George J, Stewart K, Elliott RA (2014) Improving osteoporosis management in general practice: a pharmacist-led drug use evaluation program. Drugs Aging 31:703–709. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-014-0194-0

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms. Vera Meeda for her assistance in quality evaluation of the studies, and Mr. Gregor Franssen and Mr. Stefan Jongen, medical information specialists at Maastricht University library, for their assistance in optimizing the search strategy.

Funding

Dennis Cornelissen is funded by The Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development, project number 848016001. The authors are grateful to the Prince Mutaib Chair for Biomarkers of Chronic Disease, King Saud University, Riyadh, KSA, and to the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspect of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases (ESCEO) and the WHO Collaborating Centre for Public Health Aspects of Musculoskeletal Health and Aging, for their support. The meeting of the Working Group was funded by the ESCEO, a Belgian not-for-profit organization. The ESCEO receives unrestricted educational grants, to support its educational and scientific activities, from non-governmental organizations, not-for-profit organizations, non-commercial, and corporate partners. The choice of topics, participants, content, and agenda of the Working Groups, as well as the writing, editing, submission, and reviewing of the manuscript are the sole responsibility of the ESCEO, without any influence from third parties.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Jean-Yves Reginster has received research grants from IBSA-Genévrier, Mylan, CNIEL, and Radius Health through institution, has received advisory board or consulting fees from IBSA-Genévrier, Mylan, Radius Health, and Pierre Fabre, and has received lecture fees from IBSA-Genévrier, Mylan, CNIEL, and Dairy Research Council (DRC). Mickaël Hiligsmann has received research grants from Amgen, Bayer, Radius Health, and Theramex through institution. The other authors have no conflict of interest relevant to the content of this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Pubmed

"Osteoporosis"[Mesh] OR Osteoporosis [tiab] OR "Bone Diseases, Metabolic"[Mesh] OR

Metabolic Bone Disease*[tiab] OR "Bone Demineralization, Pathologic"[Mesh] OR Bone

Demineralization[tiab] OR "Decalcification, pathologic"[MeSH Terms] OR Patholog*

Decalcification*[tiab] OR "Bone Density"[Mesh] OR Bone Densit*[Tiab]

AND

"Guideline adherence"[MeSH Terms] OR Guideline adherence*[tiab] OR "Patient

Satisfaction"[Mesh] OR Patient Satisfaction[tiab] OR "Patient Preference"[Mesh] OR Patient

Preference*[tiab] OR "Attitude to Health"[Mesh] OR Health attitude*[tiab] OR "Health

Knowledge, Attitudes Practice"[Mesh] OR "Treatment Adherence and Compliance"[Mesh] OR

Treatment Adherence [tiab] OR Therapeutic adherence [tiab] OR “Treatment compliance”[tiab]

OR “Therapeutic compliance”[tiab] OR "Patient Acceptance of Health Care"[Mesh] OR "Patient

Acceptance of Health Care"[tiab] OR "Patient Dropouts"[Mesh] OR "Patient dropout*"[tiab] OR

"Patient Participation"[Mesh] OR "Patient Participation"[tiab] OR "Patient Compliance"[Mesh]

OR Patient Compliance [tiab] OR Patient engagement [tiab] OR Patient Acceptance [tiab] OR

Patient involvement [tiab] OR Medication adherence [tiab] OR Medication persistence [tiab] OR

Medication compliance [tiab]

Embase

*metabolic bone disease/ or *bone disease/ or *bone demineralization/ or *osteoporosis/ or

*bone demineralization/

01-07-2012 t/m 31-12-2018

AND

*disease management/ or patient attitude/ or *attitude/ or *health care quality/ or *human

relation/ or *patient attendance/ or *patient compliance/ or *patient dropout/ or *patient

participation/ or *patient preference/ or *patient satisfaction/ or *refusal to participate/ or

*treatment interruption/ or *treatment refusal/ or *protocol compliance/ or *attitude to

health/ or *attitude/ or *health behavior/ or *knowledge/ or *attitude to illness/ or *health

behavior/ or *behavior/ or *medication compliance/ or *patient education/ or *health

education/

2012-2018

PSYCHINFO

(MM "Treatment Compliance" OR (MM "Compliance" OR MM "Treatment Compliance" OR MM

"Client Attitudes" OR MM "Health Attitudes" OR MM "Health Behavior" OR MM "Health Care

Utilization" OR MM "Health Education" OR MM "Health Knowledge" OR MM "Health Literacy"

OR MM "Client Education" OR MM "Client Satisfaction" OR MM "Client Participation" OR MM

"Client Attitudes" OR MM "Treatment Refusal")

AND

(MM "Osteoporosis") OR (MM "Bone Disorders")

01-07-2012 t/m 31-12-2018

Cinahl

(MM "Guideline Adherence") OR (MM "Medication Compliance") OR (MM "Patient

Compliance") OR (MM "Compliance with Medication Regimen (Saba CCC)") OR (MM

"Compliance with Therapeutic Regimen (Saba CCC)") OR (MM "Compliance with Medical

Regimen (Saba CCC)") OR (MM "Patient Satisfaction") OR (MM "Attitude to Illness") OR (MM

"Attitude to Medical Treatment") OR (MM "Attitude to Health") OR (MM "Patient Attitudes")

OR (MM "Knowledge: Health Behaviors (Iowa NOC)") OR (MM "Knowledge") OR (MM "Health

Knowledge") OR (MM "Acceptance and Commitment Therapy") OR (MM "Patient Dropouts")

AND

(MM "Osteoporosis")

01-07-2012 t/m 31-12-2018

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cornelissen, D., de Kunder, S., Si, L. et al. Interventions to improve adherence to anti-osteoporosis medications: an updated systematic review. Osteoporos Int 31, 1645–1669 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-020-05378-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-020-05378-0