Abstract

We characterize the class of weakly efficient n-person bargaining solutions that solely depend on the ratios of the players’ ideal payoffs. In the case of at least three players the ratio between the solution payoffs of any two players is a power of the ratio between their ideal payoffs. As special cases this class contains the Egalitarian and the Kalai–Smorodinsky bargaining solutions, which can be pinned down by imposing additional axioms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In a bargaining problem n players have to agree on a feasible utility allocation: if they can’t reach an agreement, they will receive strictly Pareto dominated payoffs. Since its introduction by Nash (1950) many bargaining solutions have been provided—those of Nash (1950), Kalai and Smorodinsky (1975), and the Egalitarian solution of Kalai (1977) arguably being the most influential.

While many characterizations of bargaining solutions use the axiom of Pareto efficiency, that is they require the full exploitation of the available resources, Roth (1977b) argued that in the context of bargaining such an assumption might be critical and provided a characterization of Nash’s solution without it. Following Roth, several articles have further developed efficiency-free foundations: Lensberg and Thomson (1988) presented an efficiency-free axiomatization of Nash’s solution in an environment with a variable number of agents; Anbarci and Sun (2011) derived such an axiomatization for a fixed population. An efficiency-free characterization of the Kalai–Smorodinsky solution has appeared in Rachmilevitch (2014), and an efficiency-free characterization of a generalization of Kalai’s (1977) Proportional solutions in an environment with a variable number of agents has been given by Driesen (2016).

We extend this line of literature by developing an efficiency-free axiomatization of a class of bargaining solutions that contains both the Egalitarian solution and the Kalai–Smorodinsky solution as special cases. Our approach is to replace the condition that a bargaining solution should be invariant under linear transformations by two weaker axioms, homogeneity and pairwise ratio independence. The first condition ensures that the solution of a scaled problem is the scaled solution of the original problem, given that the scaling is identical across players. The second one implies that scaling the potential payoffs of several players by the same factor does not change the solution payoff ratios of these players. The later requirement is motivated by the importance of the players’ relative payoffs when assessing the “fairness” of a bargaining solution: If any two players’ potential payoffs are scaled by the same factor, then neither should gain an advantage over the other as a result, irrespective of what happens to the other players.

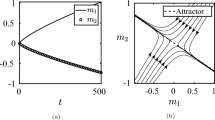

While payoffs are equal under the Egalitarian solution, the Kalai–Smorodinsky solution equalizes the ratios between the players’ payoffs and their ideal payoffs (a player’s ideal payoff is the maximal possible payoff he can achieve if everyone else receives their minimal acceptable payoffs). We find that for problems with at least three players a solution \(\mu \) satisfies our axioms if and only if there is a non-negative number p such that \(\frac{\mu _j(S)}{\mu _i(S)}=\left( \frac{a_j(S)}{a_i(S)}\right) ^p\) for all players i and j and all bargaining problems S, where a(S) is the ideal point of the problem S. It is worth mentioning that one of the criticisms of the Nash bargaining solution is precisely that it is not “fair”, in the sense that it ignores the players’ ideal payoffs (see for instance Luce and Raiffa 1957).

We denote the respective solutions by \(\mu ^p\) and it is immediate that the Egalitarian and Kalai–Smorodinsky solutions correspond to \(\mu ^0\) and \(\mu ^1\), respectively. Both solutions can be pinned down within our family of solutions by axioms that are well known when it comes to characterizing the Nash solution. We show, in particular, that combining two properties out of (1) midpoint domination, (2) being a member of \(\mu ^p\), and (3) independence of irrelevant alternatives (or disagreement convexity) uniquely pins down the Egalitarian, Nash or Kalai–Smorodinsky solution.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2 we introduce notation, definitions, and well known axioms from the literature. The main result appears in Sect. 3 and is proven in Sect. 4. Section 5 proposes further refinements so as to pin down the Egalitarian and Kalai–Smorodinsky solutions, and Sect. 6 discusses the 2-player case. Section 7 briefly concludes.

2 Preliminaries

Throughout the paper let \(\mathcal N=\{1,\ldots ,n\}\) be a finite set of players. A bargaining problem (or problem) is a pair \(\left( S,d\right) \) of a convex and comprehensiveFootnote 1 set \(S\subseteq \mathbb R^{\mathcal {N}}\) of feasible utility allocations such that \(S\cap \left( \mathbb R_{\ge 0}^{\mathcal N}-x\right) \) is compact for all \(x\in \mathbb R^{\mathcal N}\), and a disagreement point \(d\in S\). We assume throughout that there is \(s\in S\) with \(s>d\). We denote by \(e_i\) the vector with all coordinates \(j\ne i\) equal to zero and i-th coordinate equal to one. If \(s\in S\) is such that \(x\notin S\) for all \(x>s\), we say that s is weakly Pareto optimal in S. If \(s\in S\) is such that \(x\notin S\) for all \(x\ge s\) with \(x\ne s\), we say that s is strongly Pareto optimal in S. A problem \(\left( S,d\right) \) satisfies the minimal transfer property if each weakly Pareto optimal point in S is also strongly Pareto optimal. The interpretation of a problem \(\left( S,d\right) \) is that the n players need to agree on a single allocation in S. If they agree on \(s\in S\) then the bargaining situation is resolved, and each player i obtains the utility payoff \(s_i\); otherwise, everybody receives their respective disagreement value \(d_i\). The best that player i can hope for in \(\left( S,d\right) \), his ideal payoff, is \(a_i(S,d)=\max \left\{ s_i:\,s\in S, s_j\ge d_j \text { for all }j\ne i\right\} \). Note that \(a_i(S,d)>d_i\) by construction; however, typically \(a(S,d)=(a_1(S,d),\ldots ,a_n(S,d))\notin S\), i.e. this point is not feasible. A bargaining solution (or solution) is a map \(\mu \), that assigns to every problem \(\left( S,d\right) \) a unique feasible point \(\mu (S,d)\in S\). We are interested in characterizing the set of bargaining solutions with certain properties. The first one allows us to restrict our attention to the case \(d=0\).

Translation invariance. \(\mu (S+t,d+t)=t+\mu (S,d)\) for all problems (S, d) and all vectors \(t\in \mathbb R^{\mathcal N}\).

From here we assume that this axiom is always satisfied so that we can assume without loss of generality that \(d=0\) since \(\mu \left( S,d\right) =\mu \left( S-d,0\right) +d\). We will simply write S for the problem \(\left( S,0\right) \) whenever the disagreement point is irrelevant for the argument. The following five axioms are further properties a bargaining solution may satisfy.

Anonymity. \(\mu _{\pi (i)}(S)=\mu _i(\pi S)\) for all \(i\in \mathcal N\), all problems S and all permutations \(\pi \).Footnote 2

Individual monotonicity. \(\mu _i(S)\le \mu _i(T)\) for all \(i\in \mathcal N\) and all problems S, T with \(S\subseteq T\), \(a_i(S)\le a_i(T)\), and \(a_j(S)=a_j(T)\) for all \(j\ne i\).

Strong individual rationality. \(\mu (S)>0\) for all problems S.

Homogeneity. \(\mu (\lambda S)=\lambda \mu (S)\) for all problems S and all \(\lambda \in \mathbb R_{>0}\).

Independence of equivalent utility representations. \(\mu \left( k\circ S\right) =k\circ \mu \left( S\right) \) for all problems S and all \(k\in \mathbb R^{\mathcal N}_{>0}\).Footnote 3

As all these properties are well known in the bargaining literature (see for instance Peters 1992), we omit their discussion here. Note that homogeneity is implied by independence of equivalent utility representations.

3 The main result

3.1 A new class of bargaining solutions

A crucial question in bargaining is how the individual payoffs compare to each other. For instance, the Egalitarian solution of Kalai (1977), E, equalizes the payoffs; that is, \(\frac{E_j(S)}{E_i(S)}=1\) for all bargaining problems S and all \(i,j\in \mathcal N\). The solution of Kalai and Smorodinsky (1975), KS, equalizes the fractions of their ideal payoffs that players achieve; that is, \(\frac{KS_j(S)}{KS_i(S)}=\frac{a_j(S)}{a_i(S)}\) for all bargaining problems S and all \(i,j\in \mathcal N\). More generally, E and KS belong to the following class of bargaining solutions: given \(0\le p <\infty \), let \(\mu ^p\) be the solution that assigns to each S the (unique) weakly Pareto optimal point \(s\in S\) that satisfies \(\frac{s_j}{s_i}=\left( \frac{a_j(S)}{a_i(S)}\right) ^p\) for all \(i,j\in \mathcal N\). That is, for any problem S we have

where \(\lambda \) is the maximum possible. Clearly \(E=\mu ^0\) and \(KS=\mu ^1\). In general, the parameter p measures the advantage of having a large ideal payoff: for \(p=0\) there is no advantage as \(\mu ^p=E\), and as p increases this advantage increases as well.

3.2 More axioms

The following axiom has been formulated by Nash (1950).

Independence of irrelevant alternatives. \(\mu (S)=\mu (T)\) for all bargaining problems S, T with \(S\subseteq T\) and \(\mu (T)\in S\).

Although this axiom expresses a sensible idea, namely that the deletion of options that were not chosen in the first place should not affect the bargaining outcome, it implies extreme insensitivity to the shape of the problem (see for instance Roth 1977a, for a discussion and alternative independence axioms). The following is an n-person version of a weaker axiom which Dubra (2001) considered in the 2-player case.Footnote 4

Homogeneous ideal independence of irrelevant alternatives. \(\mu (S)=\mu (T)\) for all bargaining problems S, T with \(S\subseteq T\), \(\mu (T)\in S\), and \(a(S)=ra(T)\) for some \(r\le 1\).

The rationale behind this axiom is that independence of irrelevant alternatives should only be applied to pairs of “similar” problems; more precisely, problems for which the ratios of the ideal payoffs are equal.

The following axiom is new. It requires that changing the utility scales of i and j by the same factor preserves their solution-payoffs-ratio.

Pairwise ratio independence. \(\frac{\mu _i(k\circ S)}{\mu _j(k\circ S)}=\frac{\mu _i(S)}{\mu _j(S)}\) for all problems S with \(\mu (S)>0\) and all \(k\in \mathbb R^{\mathcal N}_{>0}\) with \(k_i=k_j\).

Clearly, this axiom is implied by independence of equivalent utility representations, and for \(n=2\) it is also implied by homogeneity.

3.3 The characterization

Our main result is the following Theorem.

Theorem 3.1

Let \(n\ge 3\). A solution \(\mu \) satisfies anonymity, individual monotonicity, strong individual rationality, homogeneity, homogeneous ideal independence of irrelevant alternatives, and pairwise ratio independence if and only if there exists \(p\in \mathbb {R}_{\ge 0}\) such that \(\mu =\mu ^p\).

The axioms listed in Theorem 3.1 are independent. Given a vector \(q\in \mathbb {R}_{>0}^n\) with \(q_i\ne q_j\) for some (i, j), the corresponding Proportional solutionFootnote 5 satisfies all the axioms but anonymity. The Nash solutionFootnote 6 satisfies all the axioms but individual monotonicity. The constant solution that assigns 0 to every problem satisfies all axioms but strong individual rationality. The solution

satisfies all axioms but homogeneity. The solution that assigns to each S the point \(\frac{1}{2}KS(S)\) satisfies all the axioms but homogeneous ideal independence of irrelevant alternatives. The solution that assigns to each S the point \(\lambda (2^{\frac{a_1(S)}{\sum _ja_j(S)}},\ldots ,2^{\frac{a_n(S)}{\sum _ja_j(S)}})\), where \(\lambda \) is the maximum possible, satisfies all the axioms but pairwise ratio independence.

It can easily be seen that \(\mu ^p\) also satisfy the following axiom.

Continuity. \(\lim _{k\rightarrow \infty }\mu \left( S_k\right) = \mu (S)\) for every problem S and a sequence \(\{S_k\}_{k\in \mathbb N}\) of problems with \(\lim _{k\rightarrow \infty }S_k=S\) in the Hausdorff topology.

We will discuss the role of this property in more detail in Sect. 6, but the observation that it is satisfied by \(\mu ^p\) will be useful when proving Theorem 3.1 in Sect. 4.

Remark 3.2

Both pairwise ratio independence and homogeneity are implied by independence of equivalent utility representations. But the converse is not true. In particular, if we replace pairwise ratio independence and homogeneity in Theorem 3.1 by independence of equivalent utility representations, we obtain the Kalai–Smorodinsky solution (see for instance Rachmilevitch 2014, for details).

4 Proof of Theorem 3.1

For a set \(A\subset \mathbb R^{\mathcal N}\) let \(\text {cch}\left( A\right) \) be the convex comprehensive hull of A, that is the smallest convex comprehensive set that contains A. Let \(\Delta =\left\{ x\in \mathbb R^{\mathcal N}_{\ge 0}:\, \sum _{i\in \mathcal N}x_i\le 1\right\} \) be the n-dimensional unit simplex, and for a problem S let \(\Delta (S)=\text {cch}\left( a(S)\circ \Delta \right) \), i.e. \(\Delta (S)\) is the minimal problem (with respect to set inclusion) in which the players have the same ideal payoffs as in S.

Lemma 4.1

Let \(\mu \) be a solution that satisfies individual monotonicity, strong individual rationality, homogeneity, and homogeneous ideal independence of irrelevant alternatives. Then the following holds for every problem S: \(\mu (S)\ge \lambda \mu (\Delta (S))\), where \(\lambda =\max \{\lambda '\in \mathbb R_{>0}: \lambda ' \mu (\Delta (S))\in S\}\).

Proof

Let \(x=\mu (\Delta (S))\). By strong individual rationality, \(x>0\). Let \(\lambda \) be the maximal number such that \(\lambda x\in S\), let \(T=\lambda \Delta (S)\), and let \(V= S\cap T\). By homogeneity, \(\mu (T)=\lambda \mu \left( \Delta (S)\right) \). By individual monotonicity, \(\mu (V)\le \mu (S)\). And by homogeneous ideal independence of irrelevant alternatives, \(\mu (V)=\mu (T)\). Hence \(\mu (S)\ge \mu (V)=\mu (T)=\lambda \mu \left( \Delta (S)\right) \). \(\square \)

For the remainder of this section let \(n\ge 3\) and let \(\mu \) be a bargaining solution that satisfies all the axioms of Theorem 3.1. We shall prove that \(\mu =\mu ^p\) for some \(p\ge 0\).

Lemma 4.2

There exists \(p\in \mathbb {R}_{\ge 0}\) such that \(\mu (S)=\mu ^p(S)\) for all problems S that satisfy the minimal transfer property.

Proof

For every \(i,j\in \mathcal N\), \(i\ne j\), define a function \(\psi _{i,j}:\mathbb {R}_{>0}^{\mathcal N}\rightarrow \mathbb {R}_{>0}\) by

By strong individual rationality \(\mu _i\left( a\circ \Delta \right) >0\), so \(\psi _{i,j}\) is well-defined.

Let S be a problem with the minimal transfer property. By Lemma 4.1 we have \(\mu (S)\ge \lambda \mu (\Delta (S))\), and since S has the minimal transfer property \(\lambda \mu (\Delta (S))\) is strongly Pareto optimal in S. Therefore \(\mu (S)=\lambda \mu (\Delta (S))\). Hence,

By pairwise ratio independence the above ratio only depends on \(a_i(S)\) and \(a_j(S)\), by homogeneity it only depends on the ratio \(\frac{a_j(S)}{a_i(S)}\), and by anonymity, it does not depend on i, j. Hence, there is a function \(\Psi \) such that

for all \(i,j\in \mathcal N\), and \(\Psi \) is non-decreasing by individual monotonicity.

We extend \(\Psi \) on \(\mathbb R_{\ge 0}\) by defining \(\Psi (0)=0\). We argue that \(\Psi (xy)=\Psi (x)\cdot \Psi (y)\) for all \(x,y>0\). To see this, let T be a problem with the minimal transfer property that satisfies \(\frac{a_3(T)}{a_2(T)}=x\) and \(\frac{a_2(T)}{a_1(T)}=y\). Then

From the theory of functional equations (see for instance Theorem 1.9.13 in Eichhorn 1978) we know that either \(\Psi (t)=t^p\) for some \(p>0\), or

Since \(a(S)>0\) for all bargaining problems, we have \(\frac{\mu _j(S)}{\mu _i(S)}=\left( \frac{a_j(S)}{a_i(S)}\right) ^p\) for some \(p\ge 0\) in both cases. Since \(\mu (S)=\lambda \mu (\Delta (S))\), and since the latter is strongly Pareto optimal in S, it must hold that \(\mu (S)=\mu ^p(S)\). \(\square \)

In the remainder of this section let \(p\in \mathbb R_{\ge 0}\) be such that \(\mu (S)=\mu ^p(S)\) for all problems that satisfy the minimal transfer property. The following Corollary is an easy observation after the foregoing two lemmas and is stated mainly for later reference.

Corollary 4.3

It holds that \(\mu (S)\ge \mu ^p(S)\) for every problem S. In particular, if \(\mu ^p(S)\) is strongly Pareto optimal in S then \(\mu (S)=\mu ^p(S)\).

Proof

From Lemma 4.1 and Lemma 4.2 it follows that

where the last equality holds as \(\lambda \) is such that \(\lambda \mu ^p\left( \Delta \left( S\right) \right) \) is weakly Pareto optimal in S. \(\square \)

Lemma 4.4

If \(\mu ^p(S)<a(S)\) then \(\mu (S)=\mu ^p(S)\).

Proof

Let S be such that \(\mu ^p(S)<a(S)\). Suppose that there is \(i\in \mathcal N\) such that \(\mu _i(S)>\mu _i^p(S)\), and let \(\delta >0\) be such that \(\mu _i(S)=\left( 1+\delta \right) \mu _i^p(S)\) (if there is no such i we are done, since in this case \(\mu (S)=\mu ^p(S)\) by Corollary 4.3). Let \(\varepsilon \in (0,\delta )\) be such that \(\left( 1+\varepsilon \right) \mu ^p(S)<a(S)\) and let \(U=\text {cch}\left( S\cup \{\left( 1+\varepsilon \right) \mu ^p(S)\}\right) \), which can easily be seen to be a problem. Then \(\left( 1+\varepsilon \right) \mu ^p(S)\) is a strictly positive extreme point in U and therefore strongly Pareto optimal. Therefore, by Corollary 4.3, \(\mu (U)=\mu ^p(U)=(1+\varepsilon )\mu ^p(S)\). Further, \(S\subseteq U\) and \(a(S)=a(U)\), so the individual monotonicity of \(\mu \) implies

which is impossible. \(\square \)

Corollary 4.5

If \(p=1\) then \(\mu =\mu ^1\).

Proof

If S is such that \(a(S)\in S\) then \(a(S)=\mu ^1(S)\le \mu (S)\le a(S)\). If S is such that \(a(S)\notin S\) then \(\mu ^1(S)<a(S)\) and the claim follows from Lemma 4.4. \(\square \)

For the remainder of this section we can assume without loss of generality that \(p\ne 1\). For \(k>0\) and \(i\in \mathcal {N}\), let \(k^i=ke_i+\sum _{j\ne i}e_j\in \mathbb R^{\mathcal N}\). The following technical Lemma will be very useful in the later proofs.

Lemma 4.6

For each problem S and each \(i \in \mathcal {N}\) there exists \(k > 0\) such that \(\mu _j^p\left( k^i\circ S\right) <\mu _j^p(S)\) for all \(j \in \mathcal {N} \setminus \{i\}\).

Proof

For each \(k>0\),

Since \(p \ne 1\), k can be chosen such that \(k^{1-p} < \mu _j^p(S)a_j\left( S\right) ^{-p}a_i\left( S\right) ^{p-1}\) for all \(j \in \mathcal {N} \setminus \{i\}\). (If \(p>1\) choose k very large, if \(p<1\) choose k very close to 0.) Hence, there exists \(k>0\) such that \(\mu _j^p\left( k^i\circ S\right) <\mu _j^p(S)\) for all \(j \in \mathcal {N} \setminus \{i\}\). \(\square \)

For a problem S let \(M(S)=\left\{ i\in \mathcal N:\, \mu _i(S)<a_i(S)\right\} \).

Lemma 4.7

If S is such that \(\left| M(S)\right| \ge 2\) then \(\mu (S)=\mu ^p(S)\).

Proof

Let \(S'=\text {cch}\left( \Delta (S)\cup \{\mu (S)\}\right) \) and let \(h\in M(S)\). By construction \(a_h(S')e_h\) is strongly Pareto optimal in \(S'\) and for any \(k>0\) it holds that \(a_h\left( k^h\circ S'\right) \) is strongly Pareto optimal in \(k^h\circ S'\). Therefore \(\mu _h^p\left( k^h\circ S'\right) <a_h\left( k^h\circ S'\right) \) for all \(k>0\) by strong individual rationality. By Lemma 4.6, there is \(k>0\) such that \(\mu _j^p\left( k^h\circ S'\right) <\mu _j^p(S') \le a_j(S') = a_j\left( k^h\circ S'\right) \) for each \(j \in \mathcal {N} \setminus \{h\}\). Hence \(\mu ^p\left( k^h\circ S'\right) <a\left( k^h\circ S'\right) \) and, by Lemma 4.4, \(\mu \left( k^h\circ S'\right) =\mu ^p\left( k^h\circ S'\right) \). The pairwise ratio independence of \(\mu \) and \(\mu ^p\) thus implies

for any \(i,j\in \mathcal N{\setminus }\{h\}\). Since this holds true for all \(h\in M(S)\) and since \(\left| M(S)\right| \ge 2\) one has \(\frac{\mu _i\left( S'\right) }{\mu _j\left( S'\right) }=\frac{\mu _i^p\left( S'\right) }{\mu _j^p\left( S'\right) }\) for all \(i,j\in \mathcal N\). As \(\mu ^p\left( S'\right) \) is weakly Pareto optimal in \(S'\) it must hold that \(\mu \left( S'\right) =\mu ^p\left( S'\right) \). Since \(S'\subseteq S\), \(a\left( S'\right) =a\left( S\right) \), and \(\mu \left( S\right) \in S'\) one concludes that \(\mu \left( S'\right) =\mu (S)\) by the homogeneous ideal independence of irrelevant alternatives of \(\mu \). Further, since \(\mu ^p\left( S\right) \le \mu (S)=\mu \left( S'\right) \) it holds that \(\mu ^p\left( S\right) \in S'\), and by the homogeneous ideal independence of irrelevant alternatives of \(\mu ^p\) it must hold that \(\mu ^p\left( S'\right) =\mu ^p(S)\). Hence, \(\mu \left( S\right) =\mu \left( S'\right) =\mu ^p\left( S'\right) =\mu ^p\left( S\right) \). \(\square \)

For a problem S let \(L(S)=\left\{ i\in \mathcal N:\, \mu _i\left( S\right) >\mu _i^p\left( S\right) \right\} \).

Lemma 4.8

For all problems S it holds that \(\left| L(S)\right| \le 1\).

Proof

Assume that \(\left| L(S)\right| \ge 2\), and let \(i,j \in L(S)\) with \(i \ne j\). For \(\varepsilon > 0\), let \(S' = \text {cch}\left( S \cup \left\{ (1+\varepsilon )a_i(S)e_i\right\} \right) \), and \(S'' = \text {cch}\left( S' \cup \left\{ (1+\varepsilon )a_j(S)e_j\right\} \right) \). Since \(\mu ^p\) satisfies continuity, there is \(\varepsilon >0\) such that \(\mu _i^p(S') < \mu _i(S)\) and \(\mu _j^p(S'') < \mu _j(S)\). By construction for each \(x \in S'' \cap \mathbb {R}_{>0}^{\mathcal {N}}\), it holds that \(x_i < a_i(S'')\) and \(x_j < a_j(S'')\). Hence \(i,j\in M(S'')\) so that

by the individual monotonicity of \(\mu \), Lemma 4.7, and the choice of \(\varepsilon \). Thus, since \(x_i<a_i\left( S'\right) \) for all \(x\in S'\), \(\{i,j\} \subseteq M(S')\) and, therefore, \(\mu (S') = \mu ^p(S')\) by Lemma 4.7. By the individual monotonicity of \(\mu \),

which is impossible. \(\square \)

Proof of Theorem 3.1

By Corollary 4.5 we can assume without loss of generality that \(p\ne 1\). Let S be an arbitrary problem. If \(L(S)=\emptyset \), there is nothing to show. So, suppose that \(L(S)\ne \emptyset \). Then \(\left| L(S)\right| =1\) and, in particular, \(\left| \mathcal N\setminus L(S)\right| \ge 2\). Let \(l\in L(S)\) and let \(i,j\in \mathcal N\setminus L(S)\) with \(i\ne j\). By the pairwise ratio independence of \(\mu \) and \(\mu ^p\) it holds that

for all \(k>0\); and since \(\mu _j\left( k^i\circ S\right) \ge \mu _j^p\left( k^i\circ S\right) \), we have \(\mu _l\left( k^i\circ S\right) >\mu _l^p\left( k^i\circ S\right) \). Hence, \(l\in L\left( k^i\circ S\right) \) and by Lemma 4.8 it holds that \(\mu _j\left( k^i\circ S\right) =\mu _j^p\left( k^i\circ S\right) \) for all \(k>0\). By Lemma 4.6, there is \(k>0\) such that \(\mu _j\left( k^i\circ S\right) =\mu _j^p\left( k^i\circ S\right) <\mu _j^p(S)\le \mu _j(S)\). The pairwise ratio independence of \(\mu \) thus implies \(\mu _h\left( k^i\circ S\right) <\mu _h\left( S\right) \le a_h(S)=a_h\left( k^i\circ S\right) \) for all \(h\ne i\). Hence, \(\left| M\left( k^i\circ S\right) \right| \ge n-1\ge 2\) so that \(\mu \left( k^i\circ S\right) =\mu ^p\left( k_i\circ S\right) \) by Lemma 4.7. In particular, \(\mu _l\left( k^i\circ S\right) >\mu ^p_l\left( k^i\circ S\right) =\mu _l\left( k^i\circ S\right) \) which is impossible. \(\square \)

5 The Egalitarian and the Kalai–Smorodinsky solutions

Though a wide variety of solutions have been studied in the bargaining literature, it is safe to say that the major ones are the Nash, Kalai–Smorodinsky, and Egalitarian solutions. Although the Nash solution does not belong to the family \(\left\{ \mu ^p\right\} \), there are non-trivial connections among the three that are revealed by this family. In what follows the next axiom, which is due to Sobel (1981), plays a central role.

Midpoint domination. \(\mu (S)\ge \frac{1}{n}a(S)\) for all bargaining problems S.

Midpoint domination is the requirement that the solution Pareto-dominate randomized dictatorship, which is the process where a uniform lottery selects a “dictator”, who receives his ideal payoff whereas any other player receives zero. The Kalai–Smorodinsky solution is the only member of our family that satisfies this axiom.

Proposition 5.1

A solution \(\mu ^p\) satisfies midpoint domination if and only if it is the Kalai–Smorodinsky solution, i.e. if and only if \(p=1\).

Proof

Let \(S=\text {cch}\left( \left( 2,1,\ldots ,1\right) \circ \Delta \right) \). It is easy to see that \(KS(S)=\frac{1}{n}a(S)\) and that for \(p\ne 1\) we have \(\mu ^p(S)\ne KS(S)\). In particular \(\mu _i^p(S)<KS_i(S)\) for at least one \(i\in \mathcal N\). Hence, for \(p\ne 1\) the requirement of midpoint domination is violated. \(\square \)

5.1 Independence of irrelevant alternatives

The Egalitarian solution is the only member of our family that satisfies independence of irrelevant alternatives.

Proposition 5.2

A solution \(\mu ^p\) satisfies independence of irrelevant alternatives if and only if it is the Egalitarian solution, i.e. if and only if \(p=0\).

Proof

It is well known that E satisfies independence of irrelevant alternatives and that KS does not. So, let \(\mu ^p\) be a solution that satisfies independence of irrelevant alternatives and bear in mind that \(p\ne 1\). Let \(S=\text {cch}\left( \left\{ \left( 2,1,\ldots ,1\right) \right\} \right) \) and note that \(\mu ^p(S)=(\lambda 2^p,\lambda ,\ldots ,\lambda )\) for some \(\lambda >0\). Let \(S'=\text {cch}\left( \left\{ \mu ^p(S)\right\} \right) \) and note that \(\mu ^p(S')=(\theta (\lambda 2^p)^p,\theta \lambda ^p,\ldots ,\theta \lambda ^p)\) for some \(\theta >0\). By independence of irrelevant alternatives, \(\mu ^p(S')=\mu ^p(S)\). Therefore \(\theta \lambda ^p=\lambda \) and \(\theta (\lambda 2^p)^p=\lambda 2^p\), hence \(\lambda 2^{p^2}=\lambda 2^p\), which implies \(p\in \{0,1\}\). Since \(p=1\) is impossible, \(p=0\). \(\square \)

Moulin (1983) showed that the combination of independence of irrelevant alternatives and midpoint domination characterizes the Nash solution.Footnote 7 Hence, there is no solution that is a member of \(\left\{ \mu ^p\right\} \) and satisfies midpoint domination and independence of irrelevant alternatives, but whenever two of these three properties are combined one obtains the Egalitarian, Kalai–Smorodinsky, or Nash solution.

5.2 Disagreement convexity

We will now introduce an axiom that explicitly uses the disagreement point d of a problem. This axiom was first introduced by Peters and Van Damme (1991).

Disagreement convexity. \(\mu (S,\lambda d+(1-\lambda )\mu (S,d))=\mu (S,d)\) for all bargaining problems (S, d) and all \(\lambda \in (0,1]\).

Thomson (1994) summarizes the gist of this axiom by saying that “that the move of the disagreement point in the direction of the desired compromise does not call for a revision of this compromise”. The reader is referred to Thomson (1994) for a further discussion of this axiom. Within the family \(\{\mu ^p\}\), the Egalitarian solution is the only one that satisfies disagreement convexity.

Proposition 5.3

A solution \(\mu ^p\) satisfies disagreement convexity if and only if it is the Egalitarian solution, i.e. if and only if \(p=0\).

Proof

It is well known that E satisfies disagreement convexity and KS does not (see for instance de Clippel 2007). So, let \(\mu ^p\) be a solution that satisfies disagreement convexity and bear in mind that this implies \(p\ne 1\). As before let \(S=\text {cch}\left( \left\{ \left( 2,1,\ldots ,1\right) \right\} \right) \) and recall that \(\mu ^p(S,0)=(\lambda 2^p,\lambda ,\ldots ,\lambda )\) for some \(\lambda >0\). Note that \(a\left( S-t,0\right) =a\left( S,0\right) -t\) for any \(t\in \mathbb R_{\ge 0}^{\mathcal N}\), so that

for some \(\theta >0\) by disagreement convexity and translation invariance. Hence, \(\lambda =\theta \left( 1-\frac{\lambda }{2}\right) ^p\) and \(\lambda 2^p = \theta \left( 2-\lambda 2^{p-1}\right) ^p\). This yields

and since \(\lambda >0\) and \(p\ne 1\) this equation is satisfied if and only \(p=0\). \(\square \)

In de Clippel (2007) it is shown that the Nash solution is the only solution that satisfies disagreement convexity and midpoint domination on the class of problems with the minimal transfer property; and it might fail to satisfy disagreement convexity on problems without the minimal transfer property. So, on the class of problems with the minimal transfer property there is no solution that satisfies both axioms and lies in \(\left\{ \mu ^p\right\} \), but a solution that satisfies two out of these three properties is either the Egalitarian, Kalai–Smorodinsky, or Nash solution.

6 2-Player problems

6.1 Continuity

The condition \(n\ge 3\) in Theorem 3.1 is needed for two reasons: first, it restricts the set of functions \(\Psi \) that satisfy Eq. (1) to power functions; second, it implies continuity of the bargaining solution. Adding continuity to the list of axioms and recalling that in the 2-player case pairwise ratio independence is implied by homogeneity, one obtains the following corollary from the first part of the proof of Lemma 4.2.

Corollary 6.1

Let \(n=2\). A solution \(\mu \) satisfies anonymity, individual monotonicity, strong individual rationality, homogeneity, homogeneous ideal independence of irrelevant alternatives, and continuity if and only if there exists a non-decreasing, continuous function \(\Psi \) with \(\Psi (t)\cdot \Psi (\frac{1}{t})=1\) for all \(t>0\), such that for every S the point \(\mu (S)\) is the weakly Pareto optimal point in S with \(\frac{\mu _1(S)}{\mu _2(S)}=\Psi \left( \frac{a_1(S)}{a_2(S)}\right) \).

The axioms in the foregoing corollary are independent: the relevant examples in subsection 3.3 are all continuous, and the Lexicographic Egalitarian solution satisfies (in the 2-player case) all axioms except continuity.Footnote 8

Note that the function \(\Psi \) in Corollary 6.1 need not be a power function. For example, the solution that corresponds to \(\Psi ^*\), where \(\Psi ^*(t)=t+\log t\) for \(t\ge 1\) and \(\Psi ^*(t)=[\Psi ^*(\frac{1}{t})]^{-1}\) otherwise, satisfies all axioms in Corollary 6.1.

6.2 Strong Pareto efficiency

The analysis above did not require any efficiency assumptions; specifically, no Pareto axiom was imposed. In this subsection we investigate the consequence of adding the following axiom to our analysis.

Strong Pareto efficiency. \(\mu (S)\) is strongly Pareto optimal in S for all bargaining problems S.

For \(n\ge 3\) the solutions \(\{\mu ^p\}\) do not satisfy strong Pareto efficiency. This is inevitable: Roth (1979) proved that for \(n\ge 3\) there exists no solution that satisfies strong Pareto efficiency, anonymity, and individual monotonicity.Footnote 9 For \(n=2\), however, the axioms are compatible, as demonstrated by the Kalai–Smorodinsky solution. Moreover, under strong Pareto efficiency a strict subset of the axioms from Corollary 6.1 suffices to characterize this solution.

Proposition 6.2

Let \(n=2\). A solution satisfies strong Pareto efficiency, individual monotonicity, homogeneous ideal independence of irrelevant alternatives, and continuity if and only if it is the Kalai–Smorodinsky solution.

Proof

Clearly KS satisfies the axioms. Conversely, let \(\mu \) be a solution that satisfies them. Let S be a problem, let \(\lambda _i=\frac{\mu _i(S)}{a_i(S)}\). If \(\lambda _1=\lambda _2\) then \(\mu (S)=KS(S)\), because of strong Pareto efficiency. Assume that \(\lambda _1\ne \lambda _2\). Let without loss of generality \(\lambda _1>\lambda _2\) and note that \(\lambda _1>0\) as 0 is not strongly Pareto optimal in S. Let \(S'=\{x\in S:\,x\le \lambda _1 a(S)\}\). Then \(\mu (S')=\mu (S)\) by homogeneous ideal independence of irrelevant alternatives. Define now \(S_n=\text {cch}\left( S'\cup \{\frac{n-1}{n}\lambda _1 a(S)\}\right) \). Since \(\mu (S')\) is strongly Pareto optimal in \(S'\) and since \(x_1<\lambda _1a_1(S)\) for all \(x\in S_n\setminus S'\), we have that \(\mu (S')\) is strongly Pareto efficient in \(S_n\) for all n. Further, \(\mu (S_n)\ge \mu (S')\) for all n by individual monotonicity, so that \(\mu (S_n)=\mu (S')=\mu (S)\). In particular, \(\lim _{n\rightarrow \infty }\mu (S_n)=\mu (S)\), contradicting the strong Pareto efficiency of \(\mu \). \(\square \)

A non-trivial feature of Proposition 6.2 is that it makes no use of the anonymity axiom, or any other symmetry condition. A similar result is Proposition 1 of Dubra (2001) who additionally imposed independence of equivalent utility representation. Proposition 6.2, hence, shows that this axiom in the characterization of Dubra (2001) is redundant.Footnote 10 For the independence of the axioms note that E satisfies all axioms but strong Pareto efficiency, N satisfies all axioms but individual monotonicity, the Equal Loss solutionFootnote 11 of Chun (1988) satisfies all axioms but homogeneous ideal independence of irrelevant alternatives, and the Lexicographic Egalitarian solution satisfies all axioms but continuity.

7 Conclusion

We have characterized a one-parameter family of bargaining solutions that contains both the Egalitarian and the Kalai–Smorodinsky solutions. Within this family the latter two solutions can be pinned down by additionally requiring midpoint domination or independence of equivalent utility representations for Kalai–Smorodinsky, and independence of irrelevant alternatives or disagreement convexity for the Egalitarian solution, respectively. None of our characterizations makes use of an efficiency axiom, following the line of literature that has arisen from Roth (1977b). Under the restriction to 2-person bargaining and strongly efficient solutions, a strict subset of our axioms pins down the Kalai–Smorodinsky solution. This result is non-standard, in the sense that it is a symmetry-free characterization of a symmetric solution.

Notes

We write \(x>y\) if \(x_i>y_i\) for all \(i\in \mathcal N\), and \(x\ge y\) if \(x_i\ge y_i\) for all \(i\in \mathcal N\). S is comprehensive if \(y\in S\) whenever there is \(x\in S\) with \(x\ge y\).

For a permutation \(\pi :\mathcal N\rightarrow \mathcal N\) and a problem S, we write \(\pi S=\left\{ (s_{\pi (1)},\cdots ,s_{\pi (n)}):\, s\in S\right\} \).

For two vectors \(k,x\in \mathbb R^{\mathcal N}_{>0}\) we define \(k\circ x=\left( k_ix_i\right) _{i\in \mathcal N}\). Similarly, for a problem S we define \(k\circ S=\left\{ k\circ s:\,s\in S\right\} \), that is \(k\circ S\) is the set S stretched (or shrunken) by factor \(k_i\) in dimension i.

For any given vector \(p\in \mathbb R_{>0}^N\) the corresponding Proportional solution (Kalai 1977) maps a problem S to \(\lambda p\in S\) where \(\lambda \) is the maximum possible.

The Nash solution (Nash 1950), N, maps any problem S to the unique maximizer of \(\prod _{i\in N}x_i\) in S.

Anbarci (1998) strengthened this result, by showing that it is enough to impose independence of irrelevant alternatives on triangles (he calls this axiom midpoint outcome on a linear frontier).

This solution assigns to each S the maximal point of S that Pareto-dominates E(S).

In fact Roth (1979) showed that strong Pareto efficiency, symmetry, and individual monotonicity cannot simultaneously be satisfied (symmetry, which is a weakening of anonymity, only requires that in symmetric problems—namely, those that are invariant under permutations—the players’ payoffs be identical). García-Segarra and Ginés-Vilar (2015) strengthened that result by showing that for \(n\ge 3\) there is no solution satisfying both strong Pareto efficiency and individual monotonicity.

In fact, if continuity is replaced by independence of equivalent utility representationone obtains an asymmetric Kalai–Smorodinsky solution, see Theorem 1 in Dubra (2001).

This solution assigns to each S the strongly Pareto optimal \(x\in S\) that satisfies \(a_1(S)-x_1=a_2(S)-x_2\).

References

Anbarci N (1998) Simple characterizations of the Nash and Kalai–Smorodinski solution. Theory Decis 45:255–261

Anbarci N, Sun CJ (2011) Weakest collective rationality and the Nash bargaining solution. Soc Choice Welf 37:425–429

Chun Y (1988) The equal-loss principle for bargaining problems. Econ Lett 26:103–106

de Clippel G (2007) An axiomatization of the Nash bargaining solution. Soc Choice Welf 29:201–210

Driesen B (2016) Truncated leximin solutions. Math Soc Sci 83:79–87

Dubra J (2001) An asymmetric Kalai–Smorodinsky solution. Econ Lett 73:131–136

Eichhorn W (1978) Functional equations in economics. Addison-Wesley Pub. Co., Boston

García-Segarra J, Ginés-Vilar M (2015) The impossibility of Paretian monotonic solutions: a strengthening of Roths result. Oper Res Lett 43:476–478

Kalai E (1977) Proportional solutions to bargaining situations: interpersonal utility comparisons. Econometrica 45:1623–1630

Kalai E, Smorodinsky M (1975) Other solutions to Nash’s bargaining problem. Econometrica 43:513–518

Lensberg T, Thomson W (1988) Characterizing the Nash bargaining solution without Pareto-optimality. Soc Choice Welf 5:247–259

Luce RD, Raiffa H (1957) Games and decisions: introduction and critical survey. Wiley, New York

Moulin H (1983) Le choix social utilitariste. Ecole Polytechnique Discussion Paper

Nash J (1950) The bargaining problem. Econometrica 18:155–162

Peters H (1992) Axiomatic bargaining theory. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht

Peters HJ, Van Damme E (1991) Characterizing the Nash and Raiffa bargaining solutions by disagreement point axioms. Math Oper Res 16:447–461

Rachmilevitch S (2014) Efficiency-free characterizations of the Kalai–Smorodinsky bargaining solution. Oper Res Lett 42:246–249

Roth AE (1977a) Independence of irrelevant alternatives, and solutions to Nash’s bargaining problem. J Econ Theory 16:247–251

Roth AE (1977b) Individual rationality and Nash’s solution to the bargaining problem. Math Oper Res 2:64–65

Roth AE (1979) An impossibility result concerning \(n\)-person bargaining games. Int J Game Theory 8:129–132

Sobel J (1981) Distortion of utilities and the bargaining problem. Econometrica 49:597–619

Thomson W (1994) Cooperative models of bargaining. In: Aumann R, Hart S (eds) Handbook of game theory with economic applications 2. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 1237–1284

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Hans Peters for his valuable comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Karos, D., Muto, N. & Rachmilevitch, S. A generalization of the Egalitarian and the Kalai–Smorodinsky bargaining solutions. Int J Game Theory 47, 1169–1182 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00182-018-0611-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00182-018-0611-4