Abstract

Introduction

The current study aimed to investigate the rates of anxiety, clinical depression, and suicidality and their changes in health professionals during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Materials and methods

The data came from the larger COMET-G study. The study sample includes 12,792 health professionals from 40 countries (62.40% women aged 39.76 ± 11.70; 36.81% men aged 35.91 ± 11.00 and 0.78% non-binary gender aged 35.15 ± 13.03). Distress and clinical depression were identified with the use of a previously developed cut-off and algorithm, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated. Chi-square tests, multiple forward stepwise linear regression analyses, and Factorial Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) tested relations among variables.

Results

Clinical depression was detected in 13.16% with male doctors and ‘non-binary genders’ having the lowest rates (7.89 and 5.88% respectively) and ‘non-binary gender’ nurses and administrative staff had the highest (37.50%); distress was present in 15.19%. A significant percentage reported a deterioration in mental state, family dynamics, and everyday lifestyle. Persons with a history of mental disorders had higher rates of current depression (24.64% vs. 9.62%; p < 0.0001). Suicidal tendencies were at least doubled in terms of RASS scores. Approximately one-third of participants were accepting (at least to a moderate degree) a non-bizarre conspiracy. The highest Relative Risk (RR) to develop clinical depression was associated with a history of Bipolar disorder (RR = 4.23).

Conclusions

The current study reported findings in health care professionals similar in magnitude and quality to those reported earlier in the general population although rates of clinical depression, suicidal tendencies, and adherence to conspiracy theories were much lower. However, the general model of factors interplay seems to be the same and this could be of practical utility since many of these factors are modifiable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There are many reports in the literature suggesting that health professionals are at particular risk to experience a deterioration of their mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic [23]. Clinical depression, sleep disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was also reported both in the general population as well as in health care professionals (HCP) [55, 97]. Thus, while the COVID-19 pandemic started as an epidemic of an infectious agent, it soon gained a wider content and included all effects on all aspects of human life by this condition, even the overwhelming burst of information of questionable reliability and validity (‘infodemic’) [10]. The abuse of the terms ‘trauma’ and ‘PTSD’ is such an example. The vast majority of studies reported a ‘tsunami’-scale impact on mental health. It is highly possible that this could be an exaggeration [96]. In addition, changes to social behavior, as well as working conditions, daily habits, and routines have imposed secondary stress. Higher levels of anxiety, stress, and depressive feelings have been reported, but it seems that this depends on the temporal situation and the specific events; the response is by no means homogenous [37, 85, 96, 115], [75, 104]. Apart from the effect of the virus itself, in addition, changes in social behavior, as well as in working conditions, daily habits, and routine are expected to impose further stress, especially with the expectation of an upcoming economic crisis and possible unemployment. In this frame, mental health has gained a central position as an area that is expected to be affected by the pandemic because of its threatening nature as well as because of the profound impact on the everyday life of people. Especially concerning the later, it has been suggested that lockdowns triggered feelings of loneliness, irritableness, restlessness, and nervousness in the general population [90]. Especially the expectation of an upcoming economic crisis and possible unemployment were stressful factors. Conspiracy theories and maladaptive behaviors were also prevalent, compromising the public defense against the outbreak. The issue of increased suicidality as a consequence of extreme stress and depression has been raised again [25, 84].

At the end of the day, although are several empirical data papers, their methodology varies, it is very difficult to make comparisons among countries and it is also difficult to arrive at universally valid conclusions [55, 97]. Additionally, the literature is full of opinion papers, viewpoints, perspectives, guidelines, and narrations of activities to cope with the pandemic. These borrow from previous experiences with different pandemics and utilize common sense, but, as a result, they often obscure rather than clarify the landscape. The role of mass and social media has been discussed but remains poorly understood in empirical terms.

An early meta-analysis reported high rates of anxiety (25%) and depression (28%) in the general population [86] while a second one reported that 29.6% of people experienced stress, 31.9% anxiety and 33.7% depression [92]. Not only do we need more reliable and valid data, but we also need to identify risk and protective factors to be able to recommend measures that will eventually improve public health by preventing the adverse impact on mental health and simultaneously improve health-related behaviors [4, 47, 73, 75].

The aim of the current study was to investigate the rates of anxiety, clinical depression, and suicidality and their changes in health professionals aged 18–69 internationally, during the COVID-19 pandemic. The secondary aims were to investigate their relations with several personal, interpersonal/social, and lifestyle variables. The aim also included the investigation of the spreading of conspiracy theories concerning the COVID-19 outbreak and their relationship with mental health in this specific population group.

Materials and methods

Methods

The protocol used is available in the webappendix; each question was given an ID code; these ID codes were used throughout the results for increased accuracy.

According to a previously developed method, [39, 40, 42] the cut-off score of 23/24 for the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D) scale and a derived algorithm were used to identify cases of clinical depression. This algorithm utilized the weighted scores of selected CES-D items to arrive at the diagnosis of clinical depression, and has already been validated. Cases identified by only either method were considered cases of distress (false positive cases in terms of depression), while cases identified by both the cut-off and the algorithm were considered as clinical depression. The State-Trate Anxiety Inventory-State form (STAI-S) [100] and the Risk for Assessment of Suicidality Scale (RASS) [42] were used to assess anxiety and suicidality respectively.

The data were collected online and anonymously from April 2020 through March 2021, covering periods of full implementation of lockdowns as well as of relaxations of measures in countries around the world. Announcements and advertisements were done on the social media and through news sites, but no other organized effort had been undertaken. The first page included a declaration of consent which everybody accepted by continuing with the participation.

Approval was initially given by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece, and locally concerning each participating country.

Materials

The data came from the larger COMET-G study [41].

The study population was self-selected. It was not possible to apply post-stratification on the sample as it was done in a previous study [40], because this would mean that we would utilize a similar methodology across many different countries and the population data needed were not available for all.

Statistical analysis

-

Chi-square tests were used for the comparison of frequencies when categorical variables were present and for the post hoc analysis of the results a Bonferroni-corrected method of pair-wise comparisons was utilized [69].

-

Factorial Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used to test for the main effect as well as the interaction among grouping variables concerning continuous variables. The Scheffe test was used as the post-hoc test.

-

Multiple forward stepwise linear regression analysis (MFSLRA) was performed to investigate which variables could function as predictors and contribute to the development of others (e.g. clinical depression).

To correct for multiple comparisons, the level of p<0.001 was accepted as the level of significance for ANOVA and MFSLRA results (but not for post-hoc tests)

Results

Demographics

From the 55,589 responses from 40 countries (Table 1) of the COMET study, 23.01% reported they were working in the health field. Thus, the study sample of the current paper includes 12,792 health professionals (N = 7983–62.40% women aged 39.76 ± 11.70; N = 4709–36.81% men aged 35.91 ± 11.00 and N = 100–0.78% non-binary gender aged 35.15 ± 13.03). The contribution of each country and the gender and age composition are shown in Table 1. The sex-by-specific occupation composition is shown in Table 2. The sociodemographic characteristics are shown in webtables 1,2,3,4,5,6,7 of the appendix. Details concerning various sociodemographic variables (marital status, education, work, etc. are shown in the webappendix, in webtables 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9).

History of health

Moderate or bad somatic health was reported by 16.70% and the presence of a chronic medical somatic condition was reported by 21.29%. Detailed results are shown in webtable 8. Being either relatives or caretakers of vulnerable persons was reported by 46.88% (webtable 9).

In terms of mental health history and self-harm, 8.59% had a prior history of an anxiety disorder, 10.93% of depression, 0.71% of Bipolar disorder, 0.42% of psychosis, and 2.90% of other mental disorder. Any mental disorder history was present in 23.58%. At least once, 17.20% had hurt themselves in the past and 8.20% had attempted at least once in the past. The detailed rates by sex and country are shown in webtable 10.

Family

In terms of family status, 57.86% were married, 60.02% had at least one child and only 11.42% were living alone. The responses suggested an increased need for communication with family members in 41.79%, an increased need for emotional support in 30.26%, fewer conflicts in 37.36% and increased conflicts within families for 17.77%, an improvement of the quality of relationships in 25.62%, while in most cases (90.18%) there was maintenance of basic daily routine at least somehow (webtable 11). During lockdowns 80.81% continued to work, while 47.65% expected their economic situation to worsen because of the COVID-19 outbreak (webtable 12).

Present mental health

Concerning mental health, data 47.15% reported an increase in anxiety, and 39.95% reported a worsening in depressive affect. Suicidal thoughts were increased in 10.48%. Overall, current clinical depression was present in 13.16% of the study sample (unweighted average) with male doctors and ‘non-binary genders’ having the lowest rates (7.89 and 5.88%, respectively) and ‘non-binary gender’ nurses and administrative staff having the highest (37.50%). In detail, the results are shown in Table 2. However, after taking into consideration the expected rates of current clinical depression in the population, men with positive history had the highest Relative Risk (RR = 6.47) while the lowest was observed in women without a history of mental disorder (RR = 1.81). Additionally, distress was present in 15.19%, with the highest rates being for ‘non-binary genders’ (> 30%) and the lowest for female administrative staff (12.28%). The complete rates by sex and occupation are shown in webtable 17.

Suicidal tendencies doubled according to RASS subscales scores (webtable 17) and in comparison to what is expected [42].

Persons with a history of mental disorders had higher rates of current clinical depression (24.64% vs. 9.62%, chi-square test = 454.90; df = 1; p < 0.0001) (webtable 14). In persons without mental health history, the RR ranged from 2.14 to 2.90. In persons with a mental health history, the RR was highest in those with a psychotic history (Bipolar disorder RR = 9.04; Psychosis RR = 8.08) and ranged between 3.82 and 6.40 for non-psychotic history, with the lowest RR in persons with a history of ‘other mental disorder’, in comparison to the expected prevalence of depression (3% for men and 6% for women). Of women with clinical depression, half were new cases (without any past history of mental disorder) while this was true for two thirds of men. Taking into consideration that the pandemic increased the risk by definition, the risk to develop clinical depression during the pandemic when having a previous history was highest for bipolar disorder (RR = 4.23), while the previous history of self-harm or suicidal attempts did not increase the risk (Table 3).

The mean scale scores were 43.52 ± 11.99 for the STAI-S, 19.36 ± 8.17 for the CES-D, and 70.23 ± 134.74 for the Intention subscale of the RASS. The complete results by sex and country are shown in webtable 17.

From the total sample, 5.17% reported that they often thought much or very much about committing suicide if they had the chance. Men and women had similar rates (5.76% vs. 4.69%) but those self-identified as ‘non-binary gender’ had much higher rates (17.00%). In subjects with a history of psychotic disorder or self-harm/attempt the rate was 15.45% while in those with a history of non-psychotic disorder, it was 9.76%. In persons free of any mental disorder or self-harm/attempt history the rate was as low as 2.09%. This means that the RR for the manifestation of at least moderate suicidal thoughts was equal to 7.4 for psychotic history and 3.7 for non-psychotic history. In those identified as ‘non-binary gender’, the RR was approximately equal to 3.5.

Beliefs in conspiracy theories

Approximately one third of responders accepted at least a moderate degree some non-bizarre conspiracy theory. The acceptance of inflated death rates was 44.24% while that of the 5G antenna theory was 20.81%. Doctors had the lowest rates, but impressively, 37.6% of doctors and 50.86% of nurses reported they were believing in the deliberate inflation of death rates by governments and 14.75% and 27.22% respectively were accepting the 5G theory. In detail, the responses by sex and country are shown in webtable 21.

Modeling of mental health changes during the pandemic

The presence of any mental health history acted as a risk factor for the development of current clinical depression with all chi-square tests being significant at p < 0.001. Interestingly a history of self-harm or suicidality emerged as a risk factor even for persons without reporting mental health history. In persons with only a history of self-harm or suicidality, 17.89% developed clinical depression. The combination of both self-harm and suicidal attempts history with specific mental health history revealed that subjects without any such history at all had the lowest rate or current clinical depression (9.62%), while the presence of previous self-harm/attempts increased the risk in subjects with past anxiety (29.49%) and other mental disorders (30.52%), but not clinical depression (30.46%), Bipolar disorder (30.78%) and psychoses (30.93%). The highest relative risk (RR) was calculated for history of Bipolar disorder but history of self-harm/attempt played no role (RR = 4.23). All RR values are shown in Table 2 and webtable 22. After taking into consideration that the annual incidence of depression is 0.3% [66], the calculated risk because of the pandemic for the health professionals population to develop clinical depression is RR = 30 Fig. 1.

The presence of a chronic somatic condition acted as a significant but weak risk factor for the development of clinical depression (Chi-square = 14.61, df = 1, p < 0.001; In terms of rates, 15.35% of those with a chronic somatic condition manifested clinical depression vs. 12.56% of those without (RR = 1.22).

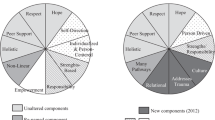

The results of the MFSLRA suggested that a significant number of variables acted either as risk or as protective factors (Table 4, Fig. 2, webtable 23). These factors explained 16.1% of the change in anxiety, 11.6% of change in depressive affect, 19.1% of the development of distress or clinical depression, and 5.1% of change in suicidal thoughts. The individual contribution of each predictor separately was very small (many b coefficients were very close to zero).

The model which was previously developed in the general population and was proven valid also in the population of health professionals. It includes multiple vulnerabilities representing the mechanism through which the COVID-19 outbreak in combination a great number of factors could lead to clinical depression through stress, and eventually to suicidality. A number of variables act as risk factors (red) or as protective factors (green), while some of them change direction of action depending on the phase (green/red). Three core clusters emerge (delineated with the doted lines)

If we consider a more or less linear continuum from fear to anxiety to depressive emotions to clinical depression and eventually to suicidality, the model which can be derived suggests there is a core of variables (Fig. 2, webfigure 1) that exert a stable either adverse or protective effect throughout the course of the development of the mental state.

Factorial ANOVA with the scores of STAI-S, CES-D and RASS as continuous variables and sex and being a doctor or a nurse as grouping variables was always significant for sex (p < 0.0001). For doctors only the interaction with sex is significant (Wilks = 0.996, F = 4.86, df = 10, error df = 25,562, p < 0.0001), with ‘non-binary genders’ having higher psychopathology. For nurses it was significant both independently (Wilks = 0.999, F = 7.768, df = 10, error df = 25,562, p = 0.009) as well as in interaction with sex (Wilks = 0.998, F = 2.618, df = 10, error df = 25,562, p = 0.004). Overall nurses had lower psychopathological scores than the rest. The Scheffe post-hoc tests (at p < 0.05) revealed that most groups defined by sex and occupation differed from each other in a complex and difficult-to-explain matrix.

Conspiracy theories manifest a complex behavior with some of them exerting a protective effect at certain phases (Fig. 2), but their overall impact was lower in comparison to the general population. The mean scores of responses to questions pertaining to different conspiracy beliefs by history of any mental disorder and current clinical depression are shown in Table 5 and webtable 24. Factorial ANOVA suggested that history of any mental disorder and current clinical depression as well as their interaction were significant factors concerning the belief in conspiracy theories (Table 5). The results of post-hoc tests are shown in webtable 25. They suggest that persons with a history of mental disorder have lower overall tendency in believing in both the threatening and the reassuring conspiracy theories. Not believing in any conspiracy theory had a different composition with history of having any mental disorder being the determining factor leading to lower adaption of conspiracy theories and with depression acting at a second level and further decreasing this tendency. These findings were consistent across disorders and conspiracy theories.

Discussion

This large international study in a convenient sample of 12,792 health professionals from 40 countries detected clinical depression in 13.31% (unweighted average) with men and ‘non-binary genders’ doctors having the lowest rates (7.89% and 5.88% respectively) and ‘non-binary gender’ nurses and administrative staff having the highest (37.50%). Distress was present in 15.19%, with the highest rates being for the ‘non-binary gender’ (> 30%) and the lowest for female administrative staff (12.28%). A significant percentage reported a deterioration in mental state, family dynamics and everyday lifestyle. Persons with a history of mental disorders had higher rates of current clinical depression (24.64%) while persons without any such history had the lowest rate or current clinical depression (9.62%). The highest rate was for the history of Bipolar disorder (40.66%; RR = 4.23). In those with a chronic somatic condition, the rate of clinical depression was 15.35% vs. 12.56% in those without (RR = 1.22). Believing in conspiracy theories was significant with at least one-third of cases accepting at least to a moderate degree a non-bizarre conspiracy.

The model developed suggested that a significant number of variables acted either as risk or as protective factors, explaining 19.1% of the development of distress or clinical depression, but their individual contribution was very small. Conspiracy theories manifested a complex behavior with some of them exerting a protective effect at certain phases. Current clinical depression acted as a risk factor and past history acted as a protective for the development of such beliefs.

The overall levels of clinical depression were lower than the rates reported in the literature, probably because of the stringent criteria of the algorithm in the current study. The large heterogeneity among countries probably reflects different phases of the pandemic in each country during the data collection. Rates of depression and mental health deterioration, in general, are probably higher in those that actually suffered from COVID-19 [29]. Other studies reported that half or more of health care professionals might suffer from depression. [7, 24, 32, 48, 76, 81, 82, 103, 117],Mira et al. 2020; [111, 112, 118]. Our results are identical to two reports [26, 52]. Meta-analyses suggested that depression rates range from 27% to 36% [45, 102, 109, 116] which is two to three times higher in comparison to our findings. In comparison, it has been reported that more than two-thirds of the general population experienced at least severe distress [18, 31, 50, 62, 80, 83, 110], and high levels of suicidality [19]. Furthermore, our findings are in accord with a recently published meta-analysis that reported much lower depression rates in the general population [21].

An important observation is that while the rate of clinical depression was much higher in persons with a history of a mental disorder the proportion of depressed persons without such a history is much higher than expected, taking into consideration that the annual incidence of depression is 0.3% [66]. This might mean that the pandemic posed a RR = 30 on the population of health professionals to develop clinical depression.

The multivariable analysis of the data allowed the current paper to confirm a staged model previously proposed concerning the effect of the pandemic on mental health (Fig. 2). This model had been developed concerning the general population and it seems that in principle it is valid for health professionals, although with some differences, especially concerning the attenuating effect of conspiracy theories and religiousness/spirituality.

According to it, with the onset of the pandemic, its psychological impact and the development of severe anxiety and distress were determined by several sociodemographic and interpersonal variables including age, fears specific to the pandemic, the quality of relationships within the family, keeping a basic daily routine, change in the economic situation, history of any mental disorder and being afraid that him/herself or a family member will get COVID-19 and die. Similar findings concerning the effects of these factors have been reported in the literature [7, 17, 32, 35, 36, 46, 56, 57, 65, 67, 70, 80, 95, 98, 107, 111,112,113], Garre-Olmo et al. 2021; [89], but until now their detailed contribution had not been identified and no comprehensive model had been developed. On the other hand, several factors not assessed by the current study, including the level of training, whether the person worked in the frontline against COVID or in an ICU, etc. [8, 54, 67, 111, 112], Mira et al. 2020; [7, 20, 24, 48, 51, 52, 71, 82, 95, 101, 103, 107] were reported as contributing in the development of clinical depression. The current paper suggests that from all health occupations, nurses might be at a higher risk to develop severe stress and clinical depression, and this is in accord with the literature [33, 48, 51, 58, 118]. Previous reports on the role of temperament are in accord with this [74]

At the pandemic onset, we might not have imagined the important role and the impact of conspiracy theories, which are largely social media driven. They are currently widely accepted as being important since the literature strongly supports their relationship with anxiety and depression [22, 28]. According to the results of the current study, approximately one-third of responders accepted at least to a moderate degree a non-bizarre conspiracy theory, and this was true both for ‘threatening’ as well as for ‘reassuring’ theories. The acceptance of inflated death rates was 44.24% while that of the 5G antenna theory was 20.81%. Doctors had the lowest rates, but impressively, 37.6% of doctors and 50.86% of nurses reported they were believing in the deliberate inflation of death rates by governments, and 14.75% and 27.22% respectively were accepting the 5G theory. Interestingly, believing in conspiracy theories pertaining to COVID-19 was lower in comparison to the general population and played an attenuated role in the development of anxiety and depression, however, these beliefs seem to be an important factor even among doctors. The high rates of believing in conspiracy theories are in accord with findings from various countries [1, 64, 91, 108] and are a worrying manifestation. Conspiracy beliefs – especially those regarding science, medicine, and health-related topics – are widespread [78], are widely distributed in social media [1, 11] and they challenge the capacity of the average person to distill and assess the content [30, 34]. They exert a well-documented adverse effect on health behaviors, especially vaccination [2, 3, 14,15,16, 43, 49, 59, 63, 72, 88, 91, 93, 99, 105]. There seems to be some relationship between believing in bizarre conspiracy theories and psychotic tendencies or a history of psychotic disorders [60].

As was found in the general population, current clinical depression and past history of mental disorders are both critical factors related to believing in conspiracy theories. Our results could mean that the critical factor which increases belief is the presence of current clinical depression, while the past history acts at a second level. As correlation does not imply causation, conspiracy theories could be either the cause of clinical depression, a copying mechanism against clinical depression, or a marker of maladaptive psychological patterns of cognitive appraisal. After taking into consideration the complete model, and especially the relationship to past mental health history, the authors propose that the beliefs in conspiracy theories are a copying mechanism against stress. The finding of the relationship between current clinical depression and believing in conspiracies is in accord with the literature [28, 44, 106], One explanation could be found in the theory concerning ‘Depressive Realism’ [5, 6], Alloy et al. 1981; [12, 68, 77] which suggests that depressive persons are more able than others to realistically interpret the world, however, this higher ability leads to pessimism.

At the most extreme end, when the emergence of suicidal thinking is possible, the family environment and family responsibilities and care act either as risk or protective factors, depending on their quality, while religiosity/spirituality and all beliefs in conspiracy theories act as protective factors, except for one which includes religious content. These results are in accord with the reports in the literature [9, 56, 57, 61, 65, 79, 113].

A difficult-to-answer question is how many of the cases detected by questionnaires and sophisticated algorithms correspond to real major clinical depression. The underlying neurobiology is opaque and maybe much diagnosed clinical depression might simply be an extreme form of a normal adjustment reaction [53]. However, there is no better way to psychometrically achieve higher validity and the algorithm we utilized is the best available method. The impressive increase in new cases of clinical depression (9.62% of persons without any history of mental disorders developed depression) which was found in our sample is in accord with the literature [87]. However, a large part of clinical depressions emerged from a previous mental health history. Of the 13.15% with current clinical depression, 7.35% were new cases while 5.80% had previous history. This suggests that almost beyond doubt true clinical depression increased by 30% (in the extreme scenario that none of cases without previous history was a case of true clinical depression. This extremely positive scenario also suggests that maybe relapses expected to occur in the next several years occurred earlier.

Concerning those without a previous history of mental disorder, it is expected that much of the adverse effects on mental health will rapidly attenuate with the end of the pandemic [27] but enduring effects will impact some vulnerable populations. So far studies investigating the long-term outcome and the long-term impact of the pandemic on mental health display equivocal findings [13, 114]. Especially sociability and the sense of belonging could be important factors determining mental health and health-related behaviors [15], and these factors seem to correspond to specific vulnerabilities seen especially in western cultures.

Conclusion

The current paper reports high rates of clinical depression, distress, and suicidal thoughts among the population of health workers during the pandemic, with a high prevalence of beliefs in conspiracy theories. For the development of clinical depression, general health status, previous mental health history, self-harm and suicidal attempts, family responsibility, economic change, and age acted as risk factors while keeping a daily routine, religiousness/spirituality, and belief in conspiracy theories were acting mostly as protective factors. These findings, although they should be closely monitored longitudinally, support previous suggestions by other authors concerning the need for a proactive intervention to protect the mental health of the general population but more specifically of vulnerable groups [38, 94]

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of the current paper include the large number of persons who filled out the questionnaire and the large bulk of information obtained, as well as the detailed way of post-stratification of the study sample.

The major limitation was that the data were obtained anonymously online through the self-selection of the responders. Additionally, the assessment included only the cross-sectional application of self-report scales, although the advanced algorithm used for the diagnosis of clinical depression corrected the problem to a certain degree. However, what is included under the umbrella of ‘clinical depression’ in the stressful times of the pandemic remains a matter of debate. Also, the lack of baseline data concerning the mental health of a similar study sample before the pandemic is also a problem.

Finally, a limitation would be that data from different countries were pooled together and with a rather large difference in numbers among countries. So the interpretation of findings should bear in mind the possible bias induced by different cultural backgrounds. However, one should have also in mind that backgrounds are not so different as one might think since the online survey of a specific professional population poses requirements that lead to similarities rather than differences among the populations from different countries. Each of these countries was also undergoing a different phase of the pandemic at each time point and phases were also different across individuals. This means that the results should be interpreted.

Data availability statement

Raw data are available upon request to the principal investigator.

References

Ahmed W, Vidal-Alaball J, Downing J, Lopez Segui F (2020) COVID-19 and the 5G conspiracy theory: social network analysis of Twitter Data. J Med Internet Res 22(5):e19458. https://doi.org/10.2196/19458

Allington D, Duffy B, Wessely S, Dhavan N, Rubin J (2021) Health-protective behaviour, social media usage and conspiracy belief during the COVID-19 public health emergency. Psychol Med 51(10):1763–1769. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329172000224X

Allington D, McAndrew S, Moxham-Hall V, Duffy B (2021) Coronavirus conspiracy suspicions, general vaccine attitudes, trust and coronavirus information source as predictors of vaccine hesitancy among UK residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Med. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721001434

Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Viscusi D (1981) Induced mood and the illusion of control. J Personal Soc Psychol 41(6):1129

Alloy LB, Abramson LY (1979) Judgment of contingency in depressed and nondepressed students: sadder but wiser? J Exp Psychol Gen 108(4):441–485. https://doi.org/10.1037//0096-3445.108.4.441

Alloy LB, Abramson LY (1988) Depressive realism: Four theoretical perspectives. Cognitive processes in depression. The Guilford Press, New York, NY, US, pp 223–265

Amin F, Sharif S, Saeed R, Durrani N, Jilani D (2020) COVID-19 pandemic- knowledge, perception, anxiety and depression among frontline doctors of Pakistan. BMC Psychiatry 20(1):459. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02864-x

Antonijevic J, Binic I, Zikic O, Manojlovic S, Tosic-Golubovic S, Popovic N (2020) Mental health of medical personnel during the COVID-19 pandemic. Brain Behav 10(12):e01881. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.1881

Arslan G, Yildirim M (2021) Meaning-based coping and spirituality during the COVID-19 pandemic: mediating effects on subjective well-being. Front Psychol 12:646572. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.646572

Asmundson GJG, Taylor S (2021) Garbage in, garbage out: the tenuous state of research on PTSD in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and infodemic. J Anxiety Disord 78:102368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2021.102368

Banerjee D, Meena KS (2021) COVID-19 as an “Infodemic” in public health: critical role of the social media. Front Public Health 9:610623. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.610623

Beck AT, Brown G, Steer RA, Eidelson JI, Riskind JH (1987) Differentiating anxiety and depression: a test of the cognitive content-specificity hypothesis. J Abnorm Psychol 96(3):179–183. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-843x.96.3.179

Bendau A, Plag J, Kunas S, Wyka S, Strohle A, Petzold MB (2021) Longitudinal changes in anxiety and psychological distress, and associated risk and protective factors during the first three months of the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany. Brain Behav 11(2):e01964. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.1964

Bertin P, Nera K, Delouvee S (2020) Conspiracy beliefs, rejection of vaccination, and support for hydroxychloroquine: a conceptual replication-extension in the COVID-19 pandemic context. Front Psychol 11:565128. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.565128

Biddlestone M, Green R, Douglas KM (2020) Cultural orientation, power, belief in conspiracy theories, and intentions to reduce the spread of COVID-19. Br J Soc Psychol 59(3):663–673. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12397

Bogart LM, Wagner G, Galvan FH, Banks D (2010) Conspiracy beliefs about HIV are related to antiretroviral treatment nonadherence among African American men with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 53(5):648–655. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181c57dbc

Bruffaerts R, Voorspoels W, Jansen L, Kessler RC, Mortier P, Vilagut G, De Vocht J, Alonso J (2021) Suicidality among healthcare professionals during the first COVID-19 wave. J Affect Disord 283:66–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.01.013

Busch IM, Moretti F, Mazzi M, Wu AW, Rimondini M (2021) What we have learned from two decades of epidemics and pandemics: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the psychological burden of frontline healthcare workers. Psychother Psychosom 90(3):178–190. https://doi.org/10.1159/000513733

Caballero-Dominguez CC, Jimenez-Villamizar MP, Campo-Arias A (2020) Suicide risk during the lockdown due to coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in Colombia. Death Stud https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2020.1784312

Celmece N, Menekay M (2020) The effect of stress, anxiety and burnout levels of healthcare professionals caring for COVID-19 patients on their quality of life. Front Psychol 11:597624. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.597624

Cenat JM, Blais-Rochette C, Kokou-Kpolou CK, Noorishad PG, Mukunzi JN, McIntee SE, Dalexis RD, Goulet MA, Labelle PR (2021) Prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psychological distress among populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res 295:113599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113599

Chen X, Zhang SX, Jahanshahi AA, Alvarez-Risco A, Dai H, Li J, Ibarra VG (2020) Belief in a COVID-19 conspiracy theory as a predictor of mental health and well-being of health care workers in Ecuador: cross-sectional survey study. JMIR Public Health Surveill 6(3):e20737. https://doi.org/10.2196/20737

Claponea RM, Pop LM, Iorga M, Iurcov R (2022) Symptoms of burnout syndrome among physicians during the outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic-a systematic literature review. Healthcare (Basel). https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10060979

Conti C, Fontanesi L, Lanzara R, Rosa I, Doyle RL, Porcelli P (2021) Burnout status of italian healthcare workers during the first COVID-19 pandemic peak period. Healthcare (Basel). https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9050510

Courtet P, Olie E (2021) Suicide in the COVID-19 pandemic: what we learnt and great expectations. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 50:118–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2021.06.005

da Silva FCT, Neto MLR (2021) Psychological effects caused by the COVID-19 pandemic in health professionals: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 104:110062. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110062

Daly M, Robinson E (2021) Anxiety reported by US adults in 2019 and during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic: population-based evidence from two nationally representative samples. J Affect Disord 286:296–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.02.054

De Coninck D, Frissen T, Matthijs K, d’Haenens L, Lits G, Champagne-Poirier O, Carignan ME, David MD, Pignard-Cheynel N, Salerno S, Genereux M (2021) Beliefs in conspiracy theories and misinformation about COVID-19: comparative perspectives on the role of anxiety, depression and exposure to and trust in information sources. Front Psychol 12:646394. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.646394

Deng J, Zhou F, Hou W, Silver Z, Wong CY, Chang O, Huang E, Zuo QK (2021) The prevalence of depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbances in COVID-19 patients: a meta-analysis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1486(1):90–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.14506

Desta TT, Mulugeta T (2020) Living with COVID-19-triggered pseudoscience and conspiracies. Int J Public Health 65(6):713–714. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-020-01412-4

Dominguez-Salas S, Gomez-Salgado J, Andres-Villas M, Diaz-Milanes D, Romero-Martin M, Ruiz-Frutos C (2020) Psycho-emotional approach to the psychological distress related to the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain: a cross-sectional observational study. Healthcare (Basel). https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8030190

Dong ZQ, Ma J, Hao YN, Shen XL, Liu F, Gao Y, Zhang L (2020) The social psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical staff in China: a cross-sectional study. Eur Psychiatry 63(1):e65. https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.59

Donkers MA, Gilissen V, Candel M, van Dijk NM, Kling H, Heijnen-Panis R, Pragt E, van der Horst I, Pronk SA, van Mook W (2021) Moral distress and ethical climate in intensive care medicine during COVID-19: a nationwide study. BMC Med Ethics 22(1):73. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-021-00641-3

Duplaga M (2020) The determinants of conspiracy beliefs related to the COVID-19 pandemic in a nationally representative sample of internet users. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17217818

Elbogen EB, Lanier M, Blakey SM, Wagner HR, Tsai J (2021) Suicidal ideation and thoughts of self-harm during the COVID-19 pandemic: the role of COVID-19-related stress, social isolation, and financial strain. Depress Anxiety. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.23162

Elhai JD, Yang H, McKay D, Asmundson GJG, Montag C (2021) Modeling anxiety and fear of COVID-19 using machine learning in a sample of Chinese adults: associations with psychopathology, sociodemographic, and exposure variables. Anxiety Stress Coping 34(2):130–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2021.1878158

Fancourt D, Steptoe A, Bu F (2021) Trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms during enforced isolation due to COVID-19 in England: a longitudinal observational study. Lancet Psychiatry 8(2):141–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30482-X

Fiorillo A, Gorwood P (2020) The consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and implications for clinical practice. Eur Psychiatry 63(1):e32. https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.35

Fountoulakis K, Iacovides A, Kleanthous S, Samolis S, Kaprinis SG, Sitzoglou K, St Kaprinis G, Bech P (2001) Reliability, validity and psychometric properties of the Greek translation of the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D) Scale. BMC Psychiatry 1:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244x-1-3

Fountoulakis KN, Apostolidou MK, Atsiova MB, Filippidou AK, Florou AK, Gousiou DS, Katsara AR, Mantzari SN, Padouva-Markoulaki M, Papatriantafyllou EI, Sacharidi PI, Tonia AI, Tsagalidou EG, Zymara VP, Prezerakos PE, Koupidis SA, Fountoulakis NK, Chrousos GP (2021) Self-reported changes in anxiety, depression and suicidality during the COVID-19 lockdown in Greece. J Affect Disord 279:624–629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.10.061

Fountoulakis KN, Karakatsoulis G, Abraham S, Adorjan K, Ahmed HU, Alarcón RD, Arai K, Auwal SS, Berk M, Bjedov S, Bobes J, Bobes-Bascaran T, Bourgin-Duchesnay J, Bredicean CA, Bukelskis L, Burkadze A, Abud IIC, Castilla-Puentes R, Cetkovich M, Colon-Rivera H, Corral R, Cortez-Vergara C, Crepin P, De Berardis D, Zamora Delgado S, De Lucena D, De Sousa A, Stefano RD, Dodd S, Elek LP, Elissa A, Erdelyi-Hamza B, Erzin G, Etchevers MJ, Falkai P, Farcas A, Fedotov I, Filatova V, Fountoulakis NK, Frankova I, Franza F, Frias P, Galako T, Garay CJ, Garcia-Álvarez L, García-Portilla MP, Gonda X, Gondek TM, González DM, Gould H, Grandinetti P, Grau A, Groudeva V, Hagin M, Harada T, Hasan TM, Hashim NA, Hilbig J, Hossain S, Iakimova R, Ibrahim M, Iftene F, Ignatenko Y, Irarrazaval M, Ismail Z, Ismayilova J, Jakobs A, Jakovljević M, Jakšić N, Javed A, Kafali HY, Karia S, Kazakova O, Khalifa D, Khaustova O, Koh S, Kopishinskaia S, Kosenko K, Koupidis SA, Kovacs I, Kulig B, Lalljee A, Liewig J, Majid A, Malashonkova E, Malik K, Malik NI, Mammadzada G, Mandalia B, Marazziti D, Marčinko D, Martinez S, Matiekus E, Mejia G, Memon RS, Martínez XEM, Mickevičiūtė D, Milev R, Mohammed M, Molina-López A, Morozov P, Muhammad NS, Mustač F, Naor MS, Nassieb A, Navickas A, Okasha T, Pandova M, Panfil A-L, Panteleeva L, Papava I, Patsali ME, Pavlichenko A, Pejuskovic B, Da Costa MP, Popkov M, Popovic D, Raduan NJN, Ramírez FV, Rancans E, Razali S, Rebok F, Rewekant A, Flores ENR, Rivera-Encinas MT, Saiz P, de Carmona MS, Martínez DS, Saw JA, Saygili G, Schneidereit P, Shah B, Shirasaka T, Silagadze K, Sitanggang S, Skugarevsky O, Spikina A, Mahalingappa SS, Stoyanova M, Szczegielniak A, Tamasan SC, Tavormina G, Tavormina MGM, Theodorakis PN, Tohen M, Tsapakis EM, Tukhvatullina D, Ullah I, Vaidya R, Vega-Dienstmaier JM, Vrublevska J, Vukovic O, Vysotska O, Widiasih N, Yashikhina A, Prezerakos PE, Smirnova D (2021) Results of the COVID-19 MEntal health inTernational for the General population (COMET-G) study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2021.10.004

Fountoulakis KN, Pantoula E, Siamouli M, Moutou K, Gonda X, Rihmer Z, Iacovides A, Akiskal H (2012) Development of the Risk Assessment Suicidality Scale (RASS): a population-based study. J Affect Disord 138(3):449–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2011.12.045

Freeman D, Loe BS, Chadwick A, Vaccari C, Waite F, Rosebrock L, Jenner L, Petit A, Lewandowsky S, Vanderslott S, Innocenti S, Larkin M, Giubilini A, Yu LM, McShane H, Pollard AJ, Lambe S (2020) COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK: the Oxford coronavirus explanations, attitudes, and narratives survey (Oceans) II. Psychol Med. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720005188

Freyler A, Simor P, Szemerszky R, Szabolcs Z, Koteles F (2019) Modern health worries in patients with affective disorders. A pilot study. Ideggyogy Sz 72(9–10):337–341. https://doi.org/10.18071/isz.72.0337

Galli F, Pozzi G, Ruggiero F, Mameli F, Cavicchioli M, Barbieri S, Canevini MP, Priori A, Pravettoni G, Sani G, Ferrucci R (2020) A systematic review and provisional metanalysis on psychopathologic burden on health care workers of coronavirus outbreaks. Front Psychiatry 11:568664. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.568664

Gambin M, Sekowski M, Wozniak-Prus M, Wnuk A, Oleksy T, Cudo A, Hansen K, Huflejt-Lukasik M, Kubicka K, Lys AE, Gorgol J, Holas P, Kmita G, Lojek E, Maison D (2021) Generalized anxiety and depressive symptoms in various age groups during the COVID-19 lockdown in Poland. Specific predictors and differences in symptoms severity. Compr Psychiatry 105:152222

Garre-Olmo J, Turro-Garriga O, Marti-Lluch R, Zacarias-Pons L, Alves-Cabratosa L, Serrano-Sarbosa D, Vilalta-Franch J, Ramos R, Girona Health Region Study G (2021) Changes in lifestyle resulting from confinement due to COVID-19 and depressive symptomatology: a cross-sectional a population-based study. Compr Psychiatry 104:152214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2020.152214

Giusti EM, Pedroli E, D’Aniello GE, Stramba Badiale C, Pietrabissa G, Manna C, Stramba Badiale M, Riva G, Castelnuovo G, Molinari E (2020) The psychological impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on health professionals: a cross-sectional study. Front Psychol 11:1684. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01684

Gu F, Wu Y, Hu X, Guo J, Yang X, Zhao X (2021) The role of conspiracy theories in the spread of COVID-19 across the United States. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073843

Gualano MR, Lo Moro G, Voglino G, Bert F, Siliquini R (2020) Effects of COVID-19 lockdown on mental health and sleep disturbances in Italy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134779

Hacimusalar Y, Kahve AC, Yasar AB, Aydin MS (2020) Anxiety and hopelessness levels in COVID-19 pandemic: a comparative study of healthcare professionals and other community sample in Turkey. J Psychiatr Res 129:181–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.07.024

Han S, Choi S, Cho SH, Lee J, Yun JY (2021) Associations between the working experiences at frontline of COVID-19 pandemic and mental health of Korean public health doctors. BMC Psychiatry 21(1):298. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03291-2

He L, Wei D, Yang F, Zhang J, Cheng W, Feng J, Yang W, Zhuang K, Chen Q, Ren Z, Li Y, Wang X, Mao Y, Chen Z, Liao M, Cui H, Li C, He Q, Lei X, Feng T, Chen H, Xie P, Rolls ET, Su L, Li L, Qiu J (2021) Functional connectome prediction of anxiety related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Psychiatry 178(6):530–540. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20070979

Hesselink G, Straten L, Gallee L, Brants A, Holkenborg J, Barten DG, Schoon Y (2021) Holding the frontline: a cross-sectional survey of emergency department staff well-being and psychological distress in the course of the COVID-19 outbreak. BMC Health Serv Res 21(1):525. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06555-5

Hill JE, Harris C, Danielle LC, Boland P, Doherty AJ, Benedetto V, Gita BE, Clegg AJ (2022) The prevalence of mental health conditions in healthcare workers during and after a pandemic: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Adv Nurs 78(6):1551–1573. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.15175

Huang Y, Zhao N (2020) Chinese mental health burden during the COVID-19 pandemic. Asian J Psychiatr 51:102052. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102052

Huang Y, Zhao N (2021) Mental health burden for the public affected by the COVID-19 outbreak in China: who will be the high-risk group? Psychol Health Med 26(1):23–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2020.1754438

Jo SH, Koo BH, Seo WS, Yun SH, Kim HG (2020) The psychological impact of the coronavirus disease pandemic on hospital workers in Daegu. South Korea. Compr Psychiatry 103:152213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2020.152213

Jolley D, Douglas KM (2014) The effects of anti-vaccine conspiracy theories on vaccination intentions. PLoS ONE 9(2):e89177. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0089177

Jolley D, Paterson JL (2020) Pylons ablaze: Examining the role of 5G COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs and support for violence. Br J Soc Psychol 59(3):628–640. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12394

Jovancevic A, Milicevic N (2020) Optimism-pessimism, conspiracy theories and general trust as factors contributing to COVID-19 related behavior - A cross-cultural study. Pers Individ Dif 167:110216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110216

Knolle F, Ronan L, Murray GK (2021) The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: a comparison between Germany and the UK. BMC Psychol 9(1):60. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-021-00565-y

Lazarevic LB, Puric D, Teovanovic P, Lukic P, Zupan Z, Knezevic G (2021) What drives us to be (ir)responsible for our health during the COVID-19 pandemic? The role of personality, thinking styles, and conspiracy mentality. Pers Individ Dif 176:110771. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.110771

Leibovitz T, Shamblaw AL, Rumas R, Best MW (2021) COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs: relations with anxiety, quality of life, and schemas. Pers Individ Dif 175:110704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.110704

Li J, Yang Z, Qiu H, Wang Y, Jian L, Ji J, Li K (2020) Anxiety and depression among general population in China at the peak of the COVID-19 epidemic. World Psychiatry 19(2):249–250. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20758

Liu Q, He H, Yang J, Feng X, Zhao F, Lyu J (2020) Changes in the global burden of depression from 1990 to 2017: findings from the Global Burden of Disease study. J Psychiatr Res 126:134–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.08.002

Liu Y, Long Y, Cheng Y, Guo Q, Yang L, Lin Y, Cao Y, Ye L, Jiang Y, Li K, Tian K, Sun C, Zhang F, Song X, Liao G, Huang J, Du L (2020) Psychological impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on nurses in China: a nationwide survey during the outbreak. Front Psychiatry 11:598712. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.598712

Lobitz WC, Post RD (1979) Parameters of self-reinforcement and depression. J Abnorm Psychol 88(1):33–41. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-843x.88.1.33

MacDonald PL, Gardner RC (2016) Type I error rate comparisons of post hoc procedures for I j Chi-Square tables. Educ Psychol Measur 60(5):735–754. https://doi.org/10.1177/00131640021970871

Mahgoub IM, Abdelrahman A, Abdallah TA, Mohamed Ahmed KAH, Omer MEA, Abdelrahman E, Salih ZMA (2021) Psychological effects of the COVID-19 pandemic: Perceived stress, anxiety, work-family imbalance, and coping strategies among healthcare professionals in Khartoum state hospitals, Sudan, 2021. Brain and behavior 11(8):e2318

Malik S, Ullah I, Irfan M, Ahorsu DK, Lin CY, Pakpour AH, Griffiths MD, Rehman IU, Minhas R (2021) Fear of COVID-19 and workplace phobia among Pakistani doctors: a survey study. BMC Public Health 21(1):833. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10873-y

Marinthe G, Brown G, Delouvee S, Jolley D (2020) Looking out for myself: Exploring the relationship between conspiracy mentality, perceived personal risk, and COVID-19 prevention measures. Br J Health Psychol 25(4):957–980. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12449

Mira JJ, Carrillo I, Guilabert M, Mula A, Martin-Delgado J, Perez-Jover MV, Vicente MA, Fernandez C, Group SA-C-SVS (2020) Acute stress of the healthcare workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic evolution: a cross-sectional study in Spain. BMJ Open 10(11):e042555. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042555

Moccia L, Janiri D, Pepe M, Dattoli L, Molinaro M, De Martin V, Chieffo D, Janiri L, Fiorillo A, Sani G, Di Nicola M (2020) Affective temperament, attachment style, and the psychological impact of the COVID-19 outbreak: an early report on the Italian general population. Brain Behav Immun 87:75–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.048

Mortier P, Vilagut G, Ferrer M, Serra C, Molina JD, Lopez-Fresnena N, Puig T, Pelayo-Teran JM, Pijoan JI, Emparanza JI, Espuga M, Plana N, Gonzalez-Pinto A, Orti-Lucas RM, de Salazar AM, Rius C, Aragones E, Del Cura-Gonzalez I, Aragon-Pena A, Campos M, Parellada M, Perez-Zapata A, Forjaz MJ, Sanz F, Haro JM, Vieta E, Perez-Sola V, Kessler RC, Bruffaerts R, Alonso J, Group MW (2021) Thirty-day suicidal thoughts and behaviors among hospital workers during the first wave of the Spain COVID-19 outbreak. Depress Anxiety 38(5):528–544. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.23129

Naser AY, Dahmash EZ, Al-Rousan R, Alwafi H, Alrawashdeh HM, Ghoul I, Abidine A, Bokhary MA, Al-Hadithi HT, Ali D, Abuthawabeh R, Abdelwahab GM, Alhartani YJ, Al Muhaisen H, Dagash A, Alyami HS (2020) Mental health status of the general population, healthcare professionals, and university students during 2019 coronavirus disease outbreak in Jordan: a cross-sectional study. Brain and behavior 10(8):e01730. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.1730

Nelson RE, Craighead WE (1977) Selective recall of positive and negative feedback, self-control behaviors, and depression. J Abnorm Psychol 86(4):379–388. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-843x.86.4.379

Oliver JE, Wood T (2014) Medical conspiracy theories and health behaviors in the United States. JAMA Intern Med 174(5):817–818. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.190

Ozdin S, Bayrak Ozdin S (2020) Levels and predictors of anxiety, depression and health anxiety during COVID-19 pandemic in Turkish society: The importance of gender. Int J Soc Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020927051

Ozdin S, Bayrak Ozdin S (2020) Levels and predictors of anxiety, depression and health anxiety during COVID-19 pandemic in Turkish society: The importance of gender. Int J Soc Psychiatry 66(5):504–511. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020927051

Pearman A, Hughes ML, Smith EL, Neupert SD (2020) Mental Health Challenges of United States Healthcare Professionals During COVID-19. Front Psychol 11:2065. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02065

Perera B, Wickramarachchi B, Samanmalie C, Hettiarachchi M (2021) Psychological experiences of healthcare professionals in Sri Lanka during COVID-19. BMC Psychol 9(1):49. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-021-00526-5

Petzold MB, Bendau A, Plag J, Pyrkosch L, Mascarell Maricic L, Betzler F, Rogoll J, Grosse J, Strohle A (2020) Risk, resilience, psychological distress, and anxiety at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany. Brain and behavior 10(9):e01745. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.1745

Pompili M (2021) Can we expect a rise in suicide rates after the Covid-19 pandemic outbreak? Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 52:1–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2021.05.011

Racine N, Hetherington E, McArthur BA, McDonald S, Edwards S, Tough S, Madigan S (2021) Maternal depressive and anxiety symptoms before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada: a longitudinal analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 8(5):405–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00074-2

Ren X, Huang W, Pan H, Huang T, Wang X, Ma Y (2020) Mental health during the Covid-19 outbreak in China: a meta-analysis. Psychiatr Q 91(4):1033–1045. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-020-09796-5

Robillard R, Daros AR, Phillips JL, Porteous M, Saad M, Pennestri MH, Kendzerska T, Edwards JD, Solomonova E, Bhatla R, Godbout R, Kaminsky Z, Boafo A, Quilty LC (2021) Emerging New Psychiatric Symptoms and the Worsening of Pre-existing Mental Disorders during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Canadian Multisite Study: Nouveaux symptomes psychiatriques emergents et deterioration des troubles mentaux preexistants durant la pandemie de la COVID-19: une etude canadienne multisite. Can J Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743720986786

Romer D, Jamieson KH (2020) Conspiracy theories as barriers to controlling the spread of COVID-19 in the U.S. Soc Sci Med 263:113356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113356

Rossi R, Jannini TB, Socci V, Pacitti F, Lorenzo GD (2021) Stressful life events and resilience during the COVID-19 lockdown measures in Italy: association with mental health outcomes and age. Front Psychiatry 12:635832. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.635832

Saladino V, Algeri D, Auriemma V (2020) The psychological and social impact of Covid-19: new perspectives of well-Being. Front Psycol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.577684

Salali GD, Uysal MS (2020) COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy is associated with beliefs on the origin of the novel coronavirus in the UK and Turkey. Psychol Med. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720004067

Salari N, Hosseinian-Far A, Jalali R, Vaisi-Raygani A, Rasoulpoor S, Mohammadi M, Rasoulpoor S, Khaledi-Paveh B (2020) Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Global Health 16(1):57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w

Sallam M, Dababseh D, Yaseen A, Al-Haidar A, Taim D, Eid H, Ababneh NA, Bakri FG, Mahafzah A (2020) COVID-19 misinformation: Mere harmless delusions or much more? A knowledge and attitude cross-sectional study among the general public residing in Jordan. PLoS ONE 15(12):e0243264. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0243264

Sani G, Janiri D, Di Nicola M, Janiri L, Ferretti S, Chieffo D (2020) Mental health during and after the COVID-19 emergency in Italy. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 74(6):372. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.13004

Schneider J, Talamonti D, Gibson B, Forshaw M (2021) Factors mediating the psychological well-being of healthcare workers responding to global pandemics: a systematic review. J Health Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1177/13591053211012759

Shevlin M, Butter S, McBride O, Murphy J, Gibson-Miller J, Hartman TK, Levita L, Mason L, Martinez AP, McKay R, Stocks TVA, Bennett K, Hyland P, Bentall RP (2021) Refuting the myth of a “tsunami” of mental ill-health in populations affected by COVID-19: evidence that response to the pandemic is heterogeneous, not homogeneous. Psychol Med. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721001665

Slusarska B, Nowicki GJ, Niedorys-Karczmarczyk B, Chrzan-Rodak A (2022) Prevalence of depression and anxiety in nurses during the first eleven months of the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031154

Solomou I, Constantinidou F (2020) Prevalence and predictors of anxiety and depression symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic and compliance with precautionary measures: age and sex matter. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17144924

Soveri A, Karlsson LC, Antfolk J, Lindfelt M, Lewandowsky S (2021) Unwillingness to engage in behaviors that protect against COVID-19: the role of conspiracy beliefs, trust, and endorsement of complementary and alternative medicine. BMC Public Health 21(1):684. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10643-w

Spielberger CD (2005) State-trait anxiety inventory for adults. Mind Garden, Redwood City California

Stuijfzand S, Deforges C, Sandoz V, Sajin CT, Jaques C, Elmers J, Horsch A (2020) Psychological impact of an epidemic/pandemic on the mental health of healthcare professionals: a rapid review. BMC Public Health 20(1):1230. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09322-z

Sun P, Wang M, Song T, Wu Y, Luo J, Chen L, Yan L (2021) The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on health care workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol 12:626547. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.626547

Suryavanshi N, Kadam A, Dhumal G, Nimkar S, Mave V, Gupta A, Cox SR, Gupte N (2020) Mental health and quality of life among healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic in India. Brain and behavior 10(11):e01837. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.1837

Taquet M, Geddes JR, Husain M, Luciano S, Harrison PJ (2021) 6-month neurological and psychiatric outcomes in 236 379 survivors of COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study using electronic health records. Lancet Psychiatry 8(5):416–427. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00084-5

Teovanovic P, Lukic P, Zupan Z, Lazic A, Ninkovic M, Zezelj I (2020) Irrational beliefs differentially predict adherence to guidelines and pseudoscientific practices during the COVID-19 pandemic. Appl Cogn Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3770

Tomljenovic H, Bubic A, Erceg N (2020) It just doesn’t feel right - the relevance of emotions and intuition for parental vaccine conspiracy beliefs and vaccination uptake. Psychol Health 35(5):538–554. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2019.1673894

Torrente M, Sousa PA, Sanchez-Ramos A, Pimentao J, Royuela A, Franco F, Collazo-Lorduy A, Menasalvas E, Provencio M (2021) To burn-out or not to burn-out: a cross-sectional study in healthcare professionals in Spain during COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Open 11(2):e044945. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044945

Uscinski J, Enders A, Klofstad C, Seelig M, Funchion J, Everett C, Wuchty S, Premaratne K, Murthi M (2020) Why do people believe COVID-19 conspiracy theories? The Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review 1 (Special Issue on COVID-19 and Misinformation)

Varghese A, George G, Kondaguli SV, Naser AY, Khakha DC, Chatterji R (2021) Decline in the mental health of nurses across the globe during COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health 11:05009. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.11.05009

Verma S, Mishra A (2020) Depression, anxiety, and stress and socio-demographic correlates among general Indian public during COVID-19. Int J Soc Psychiatry 66(8):756–762. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020934508

Vlah Tomicevic S, Lang VB (2021) Psychological outcomes amongst family medicine healthcare professionals during COVID-19 outbreak: A cross-sectional study in Croatia. Eur J Gen Pract 27(1):184–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/13814788.2021.1954154

Voorspoels W, Jansen L, Mortier P, Vilagut G, Vocht J, Kessler RC, Alonso J, Bruffaerts R (2021) Positive screens for mental disorders among healthcare professionals during the first covid19 wave in Belgium. J Psychiatr Res 140:329–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.05.024

Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, Ho RC (2020) Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051729

Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, McIntyre RS, Choo FN, Tran B, Ho R, Sharma VK, Ho C (2020) A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain Behav Immun 87:40–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.028

Wong SYS, Zhang D, Sit RWS, Yip BHK, Chung RY, Wong CKM, Chan DCC, Sun W, Kwok KO, Mercer SW (2020) Impact of COVID-19 on loneliness, mental health, and health service utilisation: a prospective cohort study of older adults with multimorbidity in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 70(700):e817–e824. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp20X713021

Yan H, Ding Y, Guo W (2021) Mental health of medical staff during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychosom Med 83(4):387–396. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000922

Yanez JA, Afshar Jahanshahi A, Alvarez-Risco A, Li J, Zhang SX (2020) Anxiety, distress, and turnover intention of healthcare workers in Peru by their distance to the epicenter during the COVID-19 crisis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 103(4):1614–1620. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.20-0800

Zerbini G, Ebigbo A, Reicherts P, Kunz M, Messman H (2020) Psychosocial burden of healthcare professionals in times of COVID-19 - a survey conducted at the University Hospital Augsburg. Ger Med Sci. https://doi.org/10.3205/000281

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed equally to the paper. KNF and DS conceived and designed the study. The other authors participated formulating the final protocol, designing and supervising the data collection and creating the final dataset. KNF and DS did the data analysis and wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors participated in interpreting the data and developing further stages and the final version of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None pertaining to the current paper.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

N. Fountoulakis, K., N. Karakatsoulis, G., Abraham, S. et al. Results of the COVID-19 mental health international for the health professionals (COMET-HP) study: depression, suicidal tendencies and conspiracism. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 58, 1387–1410 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-023-02438-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-023-02438-8