Abstract

Background

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak has been associated with stress and challenges for healthcare professionals, especially for those working in the front-line of treating COVID-19 patients. This study aimed to: 1) assess changes in well-being and perceived stress symptoms of Dutch emergency department (ED) staff in the course of the first COVID-19 wave, and 2) assess and explore stressors experienced by ED staff since the COVID-19 outbreak.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study. An online questionnaire was administered during June–July 2020 to physicians, nurses and non-clinical staff of four EDs in the Netherlands. Well-being and stress symptoms (i.e., cognitive, emotional and physical) were scored for the periods pre, during and after the first COVID-19 wave using the World Health Organization Well-Being Index (WHO-5) and a 10-point Likert scale. Stressors were assessed and explored by rating experiences with specific situations (i.e., frequency and intensity of distress) and in free-text narratives. Quantitative data were analyzed with descriptive statistics and generalized estimating equations (GEE). Narratives were analyzed thematically.

Results

In total, 192 questionnaires were returned (39% response). Compared to pre-COVID-19, the mean WHO-5 index score (range: 0–100) decreased significantly with 14.1 points (p < 0.001) during the peak of the first wave and 3.7 points (< 0.001) after the first wave. Mean self-perceived stress symptom levels almost doubled during the peak of the first wave (≤0.005). Half of the respondents reported experiencing more moral distress in the ED since the COVID-19 outbreak. High levels of distress were primarily found in situations where the staff was unable to provide or facilitate necessary emotional support to a patient or family. Analysis of 51 free-texts revealed witnessing suffering, high work pressure, fear of contamination, inability to provide comfort and support, rapidly changing protocols regarding COVID-19 care and personal protection, and shortage of protection equipment as important stressors.

Conclusions

The first COVID-19 wave took its toll on ED staff. Actions to limit drop-out and illness among staff resulting from psychological distress are vital to secure acute care for (non-)COVID-19 patients during future infection waves.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

On 30 January 2020, The World Health Organization declared the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) as a public health emergency of international concern [1]. By November 2020, more than fifty million confirmed COVID-19 cases [2] and 1.25 million deaths due to the coronavirus have been reported [3].

The COVID-19 outbreak has been associated with mental problems and challenges for many people, including healthcare professionals treating COVID-19 patients in the frontline [4,5,6]. Professionals were reported to have a high risk of experiencing mental health complaints, such as anxiety, stress, depression, sleep disturbance, loss of self-confidence, [7,8,9] as well as physical health complaints [9, 10]. Increased mental and physical health problems among healthcare staff in the midst of the pandemic can endanger the accessibility and quality of acute care. Psychological distress was reported to occur during previous virus outbreaks, and it contributed to the shortage of healthcare staff due to mental illness, sick leave or resignation [11,12,13,14]. Moreover, poor mental and physical health among staff might not only be detrimental to individuals but also may hinder professional performance and, in turn, the quality of care [15,16,17].

The impact of COVID-19 on healthcare professionals’ health status have been investigated in many previous studies [7,8,9,10]. However, they have not been adequately explored among staff working in the emergency department (ED); the most common entry point for acute hospital care. Better understanding of the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of ED staff and insight into perceived stressors could help to identify appropriate psychosocial interventions ultimately aimed at securing continuous access and high-level quality of ED care for COVID-19 and ‘regular’ emergencies throughout the course of the pandemic. Therefore, this study has two aims: first, to assess changes in well-being and perceived stress symptoms of ED staff in the course of the first COVID-19 wave in the Netherlands; and second, to assess and explore the stressors experienced by ED staff since the COVID-19 outbreak.

Methods

Study design and setting

We performed a cross-sectional survey study in the period from June 18 to July 242,020. Quantitative and qualitative data were collected through an online questionnaire from clinical and non-clinical staff of four EDs (one academic and three regional teaching hospitals) in the eastern region of the Netherlands. On February 27, 2020, the first patient with COVID-19 was hospitalized in a Dutch hospital. This date marks the start of the COVID-19 outbreak in the Netherlands [18]. Since this date the number of hospitalized COVID-19 patients rapidly increased and reached first peak levels at the end of March/early April 2020. The first wave in the Netherlands ended early June 2020.

This study is reported in accordance with the STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guideline. The local ethics committee CMO region Arnhem - Nijmegen approved the study (registration number: 2020–7145). The survey started with an informed consent of the study. Participation was only possible after reading the informed consent and selecting the “agree” option, otherwise the questionnaire could not be filled out.

Data collection

Participant recruitment and survey administration

All physicians (i.e., medical specialists and residents), nurses, nursing assistants and administrative staff (i.e., secretaries, administrative assistants, care coordinators) who worked in the ED since February 27, 2020, received a questionnaire. Eligible staff members were identified per study site by the head of the department or a senior staff member, and locally invited by e-mail to complete an online questionnaire. This email contained a standardized template consisting of general information about the study, how their personal data is stored and protected, and a link to the questionnaire. One reminder was sent 14 days after the initial invitation. In the invitation and reminder email staff members were kindly asked to fill in the questionnaire only once to avoid multiple responses from the same participant. Each participant completed the survey anonymously. Data were collected using Limesurvey – a frequently used and secured online questionnaire program – and subsequently transferred by GH to a secured database in the protected server of the Radboudumc.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire consisted of seven main sections: 1) general information on socio-demographics and occupation, 2) well-being, 3) stress symptoms, 4) moral stress; 5) experiences with stressors, 6) working climate and 7) managerial support. The data gathered on the last two sections were separately analysed in another study. General information included: gender, age, marital status, household size, caregiver tasks, professional function and hospital/study site, work experience and work-related information (i.e., contract hours, working overtime, treating COVID-19 patients). Well-being was evaluated using a Dutch version of the five-item version of the World Health Organization Well-Being Index (WHO-5) which has proven to be a valid screening tool for well-being [19]. The WHO-5 is a self-administered measure of well-being over a short time period, initially 2 weeks [20]. We asked participants to rate their well-being for three time periods: during the last 2 weeks before the COVID-19 outbreak (February 27), during the peak of the first COVID-19 wave (February 27 to April 1) and after the first COVID-19 wave (the last 2 weeks since receiving the questionnaire). In the Netherlands, the first COVID-19 wave came to an end in the beginning of June [18]. The WHO-5 consists of five positively worded items that are rated on a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (at no time) to 5 (all of the time).

Stress symptoms were evaluated for the abovementioned three time periods on a Likert scale ranging from 0 (none) to 10 (very much). We asked participants to rate symptoms related to cognitive stress (i.e., concentration problems, constant worrying, poor judgement, forgetfulness), emotional stress (i.e., anxiety, agitation, moodiness, irritability, anger, feeling overwhelmed) and physical stress (i.e., aches, pains, nausea, dizziness, rapid heart rate, hyperventilation, sleeplessness) [21]. In addition, participants were asked if they experienced more, less or the same level of moral distress since the outbreak of the COVID-19 outbreak. Moral distress has been defined as a consequence when someone knows what is ethically right but for different reasons cannot act accordingly [22, 23].

Levels of distress were assessed by rating 13 items describing specific clinical situations found to generate distress among health care staff (i.e., stressors). Participants were asked to rate, on a 5-point Likert scale, how often they experienced this situation (frequency; never-very often) and how much the situation would disturb them (intensity; not at all-very much) since the COVID-19 outbreak. Five situations were derived from the Measure of Moral Distress for Healthcare Professionals (MMD-HP) [24]. Eight situations were formulated based on findings from previous studies evaluating stress reactions by healthcare professionals during previous virus outbreaks, [12, 13] and the experiences with COVID-19 in the ED shared by colleagues. In addition, participants were invited to describe, in free-text fields, a maximum of three stressors (i.e., a specific situation or repeated factor causing distress) they had experienced in the ED since the COVID-19 outbreak.

Data analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 23.0. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize respondent’s sociodemographic and occupational characteristics, well-being, stress symptom levels, changes in moral distress, and the frequency and intensity of stressors. Frequency, percentage, mean, standard deviation (SD), median and interquartile range (IQR) scores were used according to the data type.

The raw scores on the WHO-5 items were transformed to an index score between 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating worse well-being. An index score of ≤50 indicates poor well-being and suggests further investigation into possible symptoms of depression [20]. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the WHO-5 in this study were respectively 0.90 (before the COVID-19 outbreak), 0.89 (during the peak of the first COVID-19 wave) and 0.91 (after the first COVID-19 wave). After checking WHO-5 index scores and stress symptom levels for normality, we performed generalized estimating equations (GEE) to model the development of well-being and stress symptom levels over time. We used a linear model with the outcome as a dependent variable and time as an independent factor. The GEE model took into account the correlations between repeated measurements within the same subject. An exchangeable correlation matrix was used, which means that the observations within a subject are assumed to be equally correlated. Five cases had missing values on at least one of the stress symptom variables and were excluded from the analysis. In addition, we used the Pearson’s Chi-squared test for the comparison of reported changes in moral distress per type of profession. A p value <.05 was considered to be statistically significant, based on two-sided testing. Differences (pre, during and post) in well-being and stress symptom levels were investigated across gender groups (male versus female) and types of professional function (i.e., physicians and nurses versus the rest of the respondents) using the unpaired t-test.

A mean composite distress score was calculated for each of the 13 described situations to compare levels of distress by situation and participant type. A composite distress score was calculated by multiplying frequency and intensity (0–16) with higher scores suggesting higher levels of distress. The level of distress experienced is a function of how often a situation occurs and how distressing it is when experienced [24]. The classification of low, moderate and high scores (frequency, intensity and composite score) were based on the percentiles of the means of the 13 items as shown in Additional file 1. Cases with missing values were excluded from the analysis. Additional stressors described by respondents in the free-text fields were thematically analysed in Microsoft Excel using inductive and deductive reasoning. First, two researchers (LS and GH) independently read all text fragments and inductively identified overarching themes. The final set of themes was established after discussion between both researchers. Subsequently, each description of a stressor was deductively placed under one of the identified themes, which resulted in an overview of described stressors organized per theme. For each theme, one or two text fragments were selected to illustrate experienced types of stressors.

Results

Respondent characteristics

A total of 495 eligible persons were approached to participate. One hundred ninety-two completed questionnaires were returned, resulting in a response rate of 39%. Respondents were comparable to the total population eligible to participate when looking at the gender ratio, professional function and age. A comparison is shown in Additional file 2.

Data on the characteristics of the respondents are shown in Table 1. Of the 192 respondents, 140 (72.9%) were female. Respondents had a mean age of 39.6 (SD 11.8) years. More than half (54.2%) of the respondents were nurses. The majority (83.3%) was structurally employed in the ED and treated COVID-19 patients (87.0%). A large group of respondents (40.1%) reported that their number of work shifts had increased since the COVID-19 outbreak. Of the 164 responses, 82 (50%) respondents reported to experience more moral distress in the ED since the COVID-19 outbreak. Most of these respondents were nurses (56%; < 0.001).

Changes in well-being

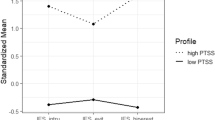

Differences were found in the mean WHO-5 index scores before, during and after the first COVID-19 wave for all respondents combined (Table 2). Compared to baseline (i.e., during the last 2 weeks before the COVID-19 outbreak), the mean WHO-5 index score decreased significantly with 14.1 points (p < 0.001) during the peak of the first wave and 3.7 points (p < 0.001) after the first wave. On average, respondents’ well-being improved after the first COVID-19 wave, but remained lower than before the COVID-19 outbreak. The development of respondents’ well-being in the course of the COVID-19 outbreak is shown in Fig. 1. Additional file 3 shows the developments of well-being per professional function and gender group. No statistically significant differences in mean WHO-5 index scores (before, during and after the first COVID-19 wave) were found across gender groups. The mean WHO-5 index score was significantly higher for physicians compared to the rest of the respondents during the peak of the first wave (p < 0.01).

Changes in self-reported stress symptoms

Differences were also found in the mean scores on self-perceived stress symptoms (Table 3). Compared to baseline, the mean score on cognitive stress symptoms increased significantly with 1.7 points (p < 0.001) during the peak of the first wave, and 0.4 points (=0.005) after the first wave. Emotional stress symptoms increased significantly with 2.1 points (p < 0.001) and 0.4 points (=0.003), respectively. Physical stress symptoms increased significantly with 1.5 points (p < 0.001) and 0.4 points (< 0.001), respectively. On average, experienced stress symptoms almost doubled during the peak of the first wave. Stress symptom levels decreased after the first COVID-19 wave, but they remained higher than before the COVID-19 outbreak. Figure 2 illustrates the development of respondents’ stress symptoms in the course of the COVID-19 outbreak. Additional file 4 shows the developments of stress symptoms per professional function and gender group. No statistically significant differences in self-perceived stress symptoms were found across gender groups, except for a higher mean score for males on emotional stress symptoms before the outbreak (p = 0.01). Compared to the rest of the respondents, physicians scored significantly lower on self-perceived emotional and physical stress symptoms during the peak of the first wave (p = 0.04 and p < 0.01 respectively).

Levels of distress on specific clinical situations since the COVID-19 outbreak

High levels of distress (i.e., composite score) were found on three of the thirteen situations, namely situations where respondents were: not able to facilitate a decent goodbye between patient and family members (item 4), not able to provide the necessary emotional support to a patient and family members (item 5), and required to care for patients that could endanger the health of their own family (item 2). Figure 3 shows the mean composite distress score for each item, by profession and overall. High scores on frequency and distress intensity were also found for the same three situations (see Additional files 5, 6 and 7). Moderate scores were found for eight situations, with highest scores in this group for: feeling unsafe due to the lack of sufficient personal protective equipment (item 3) and not being able to provide consistent and clear information to a patient or family members (item 6). None of the situations scored high on frequency and moderate-low on intensity, or vice versa. Highest distress scores were mostly found for nurses (eight situations) followed by nursing assistants (five situations).

Stressors described by respondents since the COVID-19 outbreak

Respondents described 51 stressors which were organized into six themes (Table 4). Most narratives related to witnessing patients’ and family members’ suffering (31%). The rapid health deterioration and the anxiety of patients with COVID-19, and the reactions of family members had a significant emotional impact on respondents. Nineteen percent related to increased work pressure resulting from COVID-19 care. Additional precaution measures and the preparation time needed to care for an increasing number of COVID-19 patients required the staff to work extra hard under difficult circumstances. Seventeen percent of the described situations referred to the respondents’ fear of being contaminated with the coronavirus in the ED and, in turn, fear of contaminating others. The other narratives were related to: the inability to comfort or support patients and relatives mainly because of protection measures (10%), rapidly changing protocols regarding COVID-19 care and personal protection (10%); and the shortage of high-quality personal protection equipment in the ED (10%).

Discussion

The COVID-19 outbreak had a serious impact on the well-being and mental health of ED staff. In the peak of the first wave the staff well-being dropped to a level that is close to the threshold (≤50) indicating the need for screening for depression [20]. Cognitive, emotional and physical stress symptoms almost doubled. These findings are in line with outcomes of recent meta-analyses indicating the psychological impact of COVID-19 on healthcare providers [4,5,6]. Several recent studies have demonstrated the psychological impact that COVID-19 particularly has on professionals working in emergency departments, [25,26,27] and in other frontlines such as the Intensive Care Unit [7,8,9,10, 28, 29]. Although well-being and the stress symptom levels increased after the first wave, they did not meet the reported levels before the COVID-19 outbreak. This difference may be explained by the staff mentally recovering from the first wave at the time the survey was administered. It is worrisome to notice that the ED staff did not have much time to recover given the constant flow of COVID-19 admissions and the rapid arrival of new contamination waves. Furthermore, we found lower levels of well-being and higher levels of perceived stress symptoms among nurses and supporting staff compared to physicians, which may be partly explained by nurses having closer and prolonged contact with patients compared to physicians [4].

The COVID-19 outbreak also had an impact on the psychological distress of the ED staff. A large part of the ED staff (50%) experienced more moral distress since the outbreak. Our findings showed high levels of distress, both in frequency and intensity, which were primarily caused by situations where the staff was hindered in providing the clinical and emotional care they are used to provide under ‘normal’ conditions. The use of self-evident safety precautions regarding the virus and the limited options to effectively treat COVID-19 is presumably disturbing to many professionals as they are in sharp contrast with perceived standards of good care. The fear of being exposed to COVID-19 at work and taking the infection home to their family was reported as another important stressor, also known from previous studies [10, 30, 31]. Especially nurses in this study were found to experience distress the most, which may be once again be explained by their role as the primary care giver and contact person for patients and family members in the ED. This corresponds with the findings of a recent meta-analysis on the psychological impact of COVID-19 on healthcare workers, [4] and findings from similar studies on the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak almost a decade ago, [12, 32, 33].

Respondents’ narratives revealed multiple factors causing psychological distress. Many of these factors are potentially amendable to managerial intervention. For example, by managers encouraging staff to ask for help when they need it and by offering various types of support (e.g. mental coaching, peer support and an online training module) [34,35,36]. Healthcare professionals are often self-reliant and many do not ask for help. However, this behavioural mechanism may not serve them well in a time of burgeoning workload in difficult and emotional circumstances. Moreover, a dedicated, screen-free place could help staff to destress and recuperate [37, 38]. Adjustments to the ED’s physical environment to facilitate social distancing and separating COVID-19 care from regular acute care could contribute to a safer and less stressful work environment. The use of mobile devices and applications could assist ED staff in finding ways to facilitate personal contact and to provide emotional support to COVID-19 patients and their family members. Finally, the provision of sufficient and appropriate personal protective equipment, and work rotation schedules which enable sufficient rest in the face of this ongoing pandemic seem paramount [35, 36].

To our knowledge, this study is one of the first to investigate the impact of COVID-19 on the well-being and phycological distress of various types of professionals working in multiple EDs. Several limitations of the study should however be noted. First, the response rate to our questionnaire was modest at 39%. Unfortunately, web-based survey research among healthcare professionals shows substantial variation in reported response rates and rates below 20% are not uncommon [39,40,41]. Our response rate might increase the possibility of non-response bias and under-representation of specific groups. Moreover, there is a possibility of self-selection bias where ED professionals that relate to the topics of well-being and psychological distress respond at higher rates. For reasons of confidentiality, we were unable to distinct responders from non-responders and compare both groups on statistical differences. The respondents were nevertheless comparable to the total population eligible to participate when looking at the gender ratio, professional function and age. Moreover, if respondents do not significantly differ from non-respondents with respect to the relevant characteristics, a low response rate is not necessarily associated with inferior data [39]. Second, well-being and stress symptoms were retrospectively reported by respondents over three time periods, with the first period several months ago. This may have led to recall bias and less reliable scores. Third, changes in stress symptoms were based on self-reported estimations using single-item measures that were only tested on face validity. We deliberately opted for these single items to minimize respondent burden in the midst of a pandemic. However, apart from the risk of response bias, which is commonly associated with self-reported data, [42] the use of these single items might have been insufficient in adequately capturing our constructs of interest. Fourth, our sample size consisted of staff from four EDs in one country. Although, the COVID-19 pandemic seriously affects health systems and professionals around the globe, our findings may not be representative at the international level as the demand for acute COVID-19 care and available resources may differ per country and in time.

Conclusions

This study adds to recent literature showing that he COVID-19 pandemic takes its toll on ED staff. The question is how long the frontline remains intact with the ongoing pandemic. We hope that this study contributes to a public awareness of the impact of infection peaks on ED staff. Timely and adequate actions by ED and hospital management to limit drop-out and illness among staff resulting from psychological distress are vital to secure acute care for (non)COVID-19 patients during future infection waves.

Availability of data and materials

Deidentified datasets are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus Disease 2019

- ED:

-

Emergency Department

- WHO-5:

-

World Health Organization Well-Being Index

- GEE:

-

Generalized Estimating Equations

- STROBE:

-

STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology

- MMD-HP:

-

Measure of Moral Distress for Healthcare Professionals

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

- IQR:

-

Interquartile Range

- SE:

-

Standard Error

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- PPE:

-

Personal Protection Equipment

References

World Health Organization (WHO) Emergency Committee. Statement on the second meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Geneva: WHO; 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/30-01-2020-statement-on-the-second-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov). Accessed 10 Nov 2020

Statista. Cumulative cases of COVID-19 worldwide from January 8 to November 9, 2020, by day. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1103040/cumulative-coronavirus-covid19-cases-number-worldwide-by-day/. Accessed 10 Nov 2020.

Statista. Number of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) deaths worldwide as of November 9, 2020, by country. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1093256/novel-coronavirus-2019ncov-deaths-worldwide-by-country/. Accessed 10 Oct 2020.

Batra K, Singh TP, Sharma M, Batra R, Schvaneveldt N. Investigating the psychological impact of COVID-19 among healthcare workers: a meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(23):9096. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17239096.

Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, Giannakoulis VG, Papoutsi E, Katsaounou P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:901–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026.

Luo M, Guo L, Yu M, Jiang W, Wang H. The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public - a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291:113190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113190.

Vizheh M, Qorbani M, Arzaghi SM, Muhidin S, Javanmard Z, Esmaeili M. The mental health of healthcare workers in the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2020;26:1–12.

Spoorthy MS, Pratapa SK, Mahant S. Mental health problems faced by healthcare workers due to the COVID-19 pandemic-a review. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;51:102119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102119.

Shaukat N, Ali DM, Razzak J. Physical and mental health impacts of COVID-19 on healthcare workers: a scoping review. Int J Emerg Med. 2020;13(1):40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12245-020-00299-5.

Nie A, Su X, Zhang S, Guan W, Li J. Psychological impact of COVID-19 outbreak on frontline nurses: a cross-sectional survey study. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(21-22):4217–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15454 Epub ahead of print.

Xiao J, Fang M, Chen Q, He B. SARS, MERS and COVID-19 among healthcare workers: a narrative review. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13(6):843–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2020.05.019.

Maunder R, Hunter J, Vincent L, Bennett J, Peladeau N, Leszcz M, et al. The immediate psychological and occupational impact of the 2003 SARS outbreak in a teaching hospital. CMAJ. 2003;168(10):1245–51.

Bai Y, Lin CC, Lin CY, Chen JY, Chue CM, Chou P. Survey of stress reactions among health care workers involved with the SARS outbreak. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(9):1055–7. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.55.9.1055.

Lee AM, Wong JG, McAlonan GM, et al. Stress and psychological distress among SARS survivors 1 year after the outbreak. Can J Psychiatr. 2007;52(4):233–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370705200405.

Li L, Ai H, Gao L, Zhou H, Liu X, Zhang Z, et al. Moderating effects of coping on work stress and job performance for nurses in tertiary hospitals: a cross-sectional survey in China. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):401. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2348-3.

Hall LH, Johnson J, Watt I, Tsipa A, O'Connor DB. Healthcare staff wellbeing, burnout, and patient safety: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0159015. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0159015.

Salyers MP, Bonfils KA, Luther L, Firmin RL, White DA, Adams EL, et al. The relationship between professional burnout and quality and safety in healthcare: a meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(4):475–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3886-9.

Alderweireld CEA, Buiting AGM, Murk JAN, Verweij JJ, Berrevoets MAH, van Kasteren MEE. COVID-19: patient zero in the Netherlands. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2020;164:D4962.

Hajos TR, Pouwer F, Skovlund SE, Den Oudsten BL, Geelhoed-Duijvestijn PH, Tack CJ, et al. Psychometric and screening properties of the WHO-5 well-being index in adult outpatients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 2013;30(2):e63–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.12040.

Topp CW, Østergaard SD, Søndergaard S, Bech P. The WHO-5 well-being index: a systematic review of the literature. Psychother Psychosom. 2015;84(3):167–76. https://doi.org/10.1159/000376585.

Pouwer F, Kupper N, Adriaanse MC. Does emotional stress cause type 2 diabetes mellitus? A review from the European depression in diabetes (EDID) research consortium. Discov Med. 2010;9(45):112–8.

Prentice T, Janvier A, Gillam L, Davis PG. Moral distress within neonatal and paediatric intensive care units: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2016;101(8):701–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2015-309410.

Sandeberg M, Bartholdson C, Pergert P. Important situations that capture moral distress in paediatric oncology. BMC Med Ethics. 2020;21(1):6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-020-0447-x.

Epstein EG, Whitehead PB, Prompahakul C, Thacker LR, Hamric AB. Enhancing understanding of moral distress: the measure of moral distress for health care professionals. AJOB Empir Bioeth. 2019;10(2):113–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/23294515.2019.1586008.

Song X, Fu W, Liu X, Luo Z, Wang R, Zhou N, et al. Mental health status of medical staff in emergency departments during the coronavirus disease 2019 epidemic in China. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:60–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.06.002.

An Y, Yang Y, Wang A, Li Y, Zhang Q, Cheung T, et al. Prevalence of depression and its impact on quality of life among frontline nurses in emergency departments during the COVID-19 outbreak. J Affect Disord. 2020;276:312–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.047.

Rodriguez RM, Montoy JCC, Hoth KF, Talan DA, Harland KK, Eyck PT, et al. Symptoms of anxiety, burnout, and PTSD and the mitigation effect of serologic testing in emergency department personnel during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Emerg Med. 2021:S0196-0644(21)00108-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2021.01.028.

Azoulay E, De Waele J, Ferrer R, et al. Symptoms of burnout in intensive care unit specialists facing the COVID-19 outbreak. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10(1):110. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-020-00722-3.

Shen X, Zou X, Zhong X, Yan J, Li L. Psychological stress of ICU nurses in the time of COVID-19. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):200. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-02926-2.

Tengilimoğlu D, Zekioğlu A, Tosun N, Işık O, Tengilimoğlu O. Impacts of COVID-19 pandemic period on depression, anxiety and stress levels of the healthcare employees in Turkey. Leg Med (Tokyo). 2021;48:101811. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.legalmed.2020.101811.

Shanafelt T, Ripp J, Trockel M. Understanding and addressing sources of anxiety among health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2133–4. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.5893.

Nickell LA, Crighton EJ, Tracy CS, al-Enazy H, Bolaji Y, Hanjrah S, et al. Psychosocial effects of SARS on hospital staff: survey of a large tertiary care institution. CMAJ. 2004;170(5):793–8. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.1031077.

Wong TW, Yau JK, Chan CL, Kwong RS, Ho SM, Lau CC, et al. The psychological impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak on healthcare workers in emergency departments and how they cope. Eur J Emerg Med. 2005;12(1):13–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/00063110-200502000-00005.

Chen Q, Liang M, Li Y, Guo J, Fei D, Wang L, et al. Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(4):e15–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30078-X.

Poonian J, Walsham N, Kilner T, Bradbury E, Brooks K, West E. Managing healthcare worker well-being in an Australian emergency department during the COVID-19 pandemic. Emerg Med Australas. 2020;32(4):700–2. https://doi.org/10.1111/1742-6723.13547.

Muller AE, Hafstad EV, Himmels JPW, Smedslund G, Flottorp S, Stensland SØ, et al. The mental health impact of the covid-19 pandemic on healthcare workers, and interventions to help them: a rapid systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2020;293:113441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113441.

Saqib A, Rampal T. Quality improvement report: setting up a staff well-being hub through continuous engagement. BMJ Open Qual. 2020;9(3):e001008. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjoq-2020-001008.

Zaidi SR, Sharma VK, Tsai SL, Flores S, Lema PC, Castillo J. Emergency department well-being initiatives during the COVID-19 pandemic: An after-action review. AEM Educ Train. 2020;4(4):411–4. https://doi.org/10.1002/aet2.10490.

Dykema J, Jones NR, Piché T, Stevenson J. Surveying clinicians by web: current issues in design and administration. Eval Health Prof. 2013;36(3):352–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163278713496630.

Wiebe ER, Kaczorowski J, MacKay J. Why are response rates in clinician surveys declining? Can Fam Physician. 2012;58(4):e225–8.

Oerlemans AJM, Wollersheim H, van Sluisveld N, van der Hoeven JG, Dekkers WJM, Zegers M. Rationing in the intensive care unit in case of full bed occupancy: a survey among intensive care unit physicians. BMC Anesthesiol. 2016;16:25.

Rosenman R, Tennekoon V, Hill LG. Measuring bias in self-reported data. Int J Behav Healthc Res. 2011;2(4):320–32. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBHR.2011.043414.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the efforts of our survey respondents who took valuable time away from their day jobs to participate in this work. We thank the management of the four EDs for participating in this study. We also want to acknowledge Reinier Akkermans for his assistance in the statistical analysis of data.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GH and YS designed the study and supervised the conduct of the study. LS, LG, DB, JH and AB were responsible for the recruitment of participants and data collection. GH and LS analyzed and interpreted the survey data. GH drafted the manuscript, which was critically revised for important intellectual content by all other authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The local ethics commission (CMO Arnhem- Nijmegen region) approved the study (registration number: 2020–7145). The survey started with an informed consent of the study. Participation was only possible after reading the informed consent and selecting the “agree” option, otherwise the questionnaire could not be filled out.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

The classification of distress composite, frequency and intensity scores into low, moderate and high.

Additional file 2: Table S2.

Respondents compared to all eligible persons approached for study participation on gender, age and professional function.

Additional file 3: Figure S1.

Longitudinal modelling on mean WHO-5 index scores per professional function. Figure S2. Longitudinal modelling on mean WHO-5 index scores per gender group.

Additional file 4: Figure S1.

Longitudinal modelling on mean cognitive stress symptom scores per professional function. Figure S2. Longitudinal modelling on mean cognitive stress symptom scores per gender group. Figure S3. Longitudinal modelling on mean emotional stress symptom scores per professional function. Figure S4. Longitudinal modelling on mean emotional stress symptom scores per gender group. Figure S5. Longitudinal modelling on mean physical stress symptom scores per professional function. Figure S6. Longitudinal modelling on mean physical stress symptom scores per gender group.

Additional file 5.

Table. Composite distress score, frequency and intensity of distress on thirteen specific clinical situations, overall and by profession.

Additional file 6.

Figure. Mean frequency score, overall and by profession.

Additional file 7.

Figure. Mean intensity score, overall and by profession.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hesselink, G., Straten, L., Gallée, L. et al. Holding the frontline: a cross-sectional survey of emergency department staff well-being and psychological distress in the course of the COVID-19 outbreak. BMC Health Serv Res 21, 525 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06555-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06555-5