Abstract

This paper presents a review of agroforestry in Africa from a gender perspective. It examines women’s participation relative to men and the challenges and successes they experience. Particular agroforestry practices examined include fodder production and utilization, soil fertility management, woodlots and indigenous fruit and vegetable production and processing. The review shows that agroforestry has the potential to offer substantial benefits to women; however, their participation is low in enterprises that are considered men’s domain, such as timber and high in enterprises that have little or no commercial value, such as collection of indigenous fruits and vegetables. Furthermore, the degree of women’s involvement relative to men in technologies such as soil fertility management, fodder production and woodlots is fairly high in terms of proportion of female-headed households participating but is low as measured by the area they allocate to these activities and the number of trees they plant. Data on whether women are able to manage agroforestry practices as well as men are mixed, although it is clear that women do most of the work. In cases where they do not perform well, the reasons are mostly due to scarcity of resources. In marketing, women are confined to the lower end of the value chain (retailing), which limits their control over and returns from the productive process. In order to promote gender equity in agroforestry and to ensure that women benefit fully, the paper recommends various policy, technological and institutional interventions. These include (1) facilitating women to form and strengthen associations, (2) assisting women to improve productivity and marketing of products considered to be in womens’ domain and (3) improving women’s access to information by training more women extension staff, holding separate meetings for women farmers, and ensuring that women are fully represented in all activities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Since the 1995 women’s conference in Beijing, donors, policy makers and development practitioners have pointed out the critical role of gender in development programmes (Doss 2001; IFAD 2003; World Bank 2007; IFPRI 2007; Peterman et al. 2010; Quisumbing and Pandolfelli 2010; Meinzen-Dick et al. 2010). There is a general consensus that gender inequalities in areas such as ownership and access to resources, land tenure systems, education, extension and health have contributed to lower agricultural productivity and higher poverty levels. Given that gender matters in all spheres of production, there has been a lot documented on gender issues in agricultural production. However, very little is understood about gender and adoption of agroforestry technologies, that is, ones in which perennial trees and shrubs are deliberately grown on the same land management system as annual crops and/or livestock. This paper intends to fill this gap by presenting a review of the participation of women relative to men in various agroforestry practices across the African continent. The aim is to come up with strategies that challenge imbalances thus ensuring gender equity. Participation is viewed from a broader perspective and is guided by four research questions; (i) What is the proportion of women participating in agroforestry? (ii) Are women able to manage agroforestry technologies? (iii) Do women benefit from agroforestry and how? (iv) Do women have access to agroforestry information? Each of the questions is analysed relative to men and by practice. Agroforestry practices examined include fodder production and utilization, soil fertility improvement technologies, fruit and vegetable production and processing and woodlot technology. The paper draws on lessons learned to make recommendations on how to promote efficient participation of women in agroforestry.

The focus on women and the adoption of agroforestry practices is important for various reasons. Agroforestry is a common system of production throughout Africa (Zomer et al. 2009). At the center of this type of farming system are women farmers who are frequently responsible for managing trees and as with other agricultural enterprises they do most of the work especially during the initial stages of establishment i.e. planting, weeding and watering. For example, in Kenya and Uganda, the proportion of households in which women managed fodder shrubs was over 80% (Franzel et al. 2002a; Nyeko et al. 2004). In the parklands of west Africa and in southern Africa, women are the main collectors of indigenous fruits (Campbell 1987; Schreckenberg 2004; Kalaba et al. 2009). However, despite their heavy responsibility, women’s decision making power in households is limited to byproducts of men’s trees, subsistence crops that have low returns on labour and those that involve less advanced technologies (Rocheleau and Edmunds 1997; Chikoko 2002).

Secondly, agroforestry is a low-cost system that requires minimal inputs and offers a diversity of products and services such as fodder, food, timber, fruits and soil fertility improvement. It offers immense opportunities to women who in most cases cannot afford to adopt high cost technologies due to their severe cash and credit constraints. Table 1 shows the resource requirements for four different ways women farmers can supply their families with basic household products: collect them from off the farm, buy them, grow annual crops, or practice agroforestry. Collecting off the farm requires only labour but women’s time is scarce and supplies are often located at too great a distance from the farm. Purchasing fuelwood, fodder and fruits is an option but women are acutely cash-constrained. Annual crops are options for providing fodder and a few fruits but require land and labour which are often scarce. Agroforestry has obvious advantages relative to the other three options. It requires relatively little land and labour as trees can be planted around the homestead and on field boundaries e.g., weeding is only necessary during early growth and if trees are mixed with annual crops, then no extra weeding is required. Furthermore, many trees require no cash inputs or only minimal amounts for the purchase of seed or seedlings. Third, women are increasingly assuming leadership roles and decision-making in the absence of men in many households. Female-headed households (FHHs) account for 30% of all rural smallholder households in Malawi (Gladwin et al. 2001) and over 50% in western Kenya and in Zimbabwe (Skapa 1988; Wangila et al. 1999). This is due to a number of reasons with the main one being rural–urban migration of men in search of off-farm income. This therefore places the responsibility for obtaining food, fuelwood, fodder and other tree products for the family to women.

Despite their important role in agricultural production, women remain disadvantaged in the agricultural sector due to cultural, sociological and economic factors. Such factors include limited access to resources and household decision-making. Such resources that are directly linked to agroforestry include land and tree resources, finance, extension information, labour and appropriate technology. Furthermore, many African societies have taboos that prohibit women from undertaking certain activities, which may limit their participation in developmental interventions such as agroforestry. These factors have implications on adoption of agroforestry interventions and therefore it is important to highlight them.

Areas in which women are disadvantaged

Land and tree tenure

Women in Africa have limited rights to land except in isolated cases. This is because land tenure systems in many parts of Africa grant rights to own and dispose of land to adult males (Place 1994). While there is tremendous variation across the African continent, the bottom line is that in patrilineal societies, women’s rights are often through ties to their husbands and these rights according to Gray and Kevane (undated) may cease to exist upon divorce, widowhood or failure to have a son. Even in matrilineal societies such as in western Ghana, women do not possess inheritance rights. Land is transferred from a deceased man to his brother or nephew (sister’s son) in accordance with the decision of the matrineal clan (Quisumbing et al. 2001).

Tree tenure is the right of owning and using trees. Different parts of trees and any benefits from their harvesting, sale or use may entail different rights of ownership and use among men and women. However, men usually have the overall authority as pertains to tree products that are considered to have high returns. For instance, women among the Luo and Luhya communities of Nyanza and Western Provinces of Kenya respectively have rights of collection and use of fruits, but are restricted from harvesting fuelwood of high value timber trees such as Markhamia lutea and Albizia spp. (Bradley 1991; Rocheleau and Edmunds 1997). A species such as Sesbania sesban, which is good for fuelwood and soil fertility improvement is considered a woman’s tree and therefore they have the authority to plant, manage, use and dispose of it as they please. Among the Akamba community of Eastern Kenya, Rocheleau and Edmunds (1997) report that tree planting and felling have been primarily a male’s domain, while women have enjoyed use and access rights to fodder, fuelwood, fiber, fruits and mulch. Tree products such as charcoal, logs, timber, large branches and poles are considered a male domain.

Domesticated fruit trees of commercial and economic importance such as mangoes, papayas and oranges are known to be planted and harvested by both men and women in many parts of Africa (Okigbo 1980). There are however certain fruit trees that are considered to be traditionally feminine crops because they are considered subsistence and grown around the homestead. Bush mango (Irvingia gabonensis), bread fruit (Artocarpus altilis), oil bean tree (Pentaclethra macrophylla), bananas (Musa sapientum) and plantain (Musa paradisiaca) are planted and processed by women in west Africa (Nwonwu 1996). In parklands of west Africa, women are responsible for the collection and processing of Vitellaria paradoxa (shea nut) and therefore men normally retain these trees for their wives (Schreckenberg 2004).

Household decision-making

Gender related decision-making which is often linked to intrahousehold resource allocation is an important determinant of the adoption of agroforestry technologies by both men and women. There is considerable evidence that women’s decision making power in households is limited to byproducts of men’s trees, subsistence crops that have low returns on labour and those that involve less advanced technologies (Abbas 1997; Rocheleau and Edmunds 1997; Chikoko 2002). Furthermore, women normally have obligations to provide labour for male controlled fields (Abbas 1997). According to Chavangi (1994), the general understanding in western Kenya among the Luhya community for instance is that the husband, as the head of household, has the overall control of the household resources and in that capacity, everything in the household is viewed as belonging to him. The wife is therefore expected to seek the opinion of her husband and ultimately his consent before going ahead with any plans that may bring about any changes in the allocation of household’s resources. In a study in western Kenya where the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) was testing hedgerow intercropping in the early 1990s, observations made about decision making among the Luo and Luhya were not rigidly divided by gender domains although men had significant decision making power especially in cases where there was conflict in the use of resources i.e. how much of the pruning to use as mulch and fodder respectively (David 1998). Similarly, in southeastern Nigeria, the same trend was observed among the Igbo community (Francis and Atta-Krah 1989). Among the Akamba community of Eastern Kenya, male heads of households are the main decision makers on matters of tree planting as recorded in 45.6% of the cases studied by Muok et al. (1998). Cases where both husband and wife made decisions about tree planting were 21.1% while 14.4% of decision making was made by women who either had husbands working away from home or were widows. As regards to who makes decisions on harvesting of tree products, Chikoko (2002) noted that women’s decision power in Malawi was dependant on the part of the tree. Women’s influence on harvesting decisions decreases and men’s increases as decisions move from twigs to the trunk.

Access to financial resources

Access to financial resources such as credit, is linked to women’s access to property, land, education and information (ILO 1998). Restricted ownership of land impedes women from obtaining guarantees, which would enable them to secure access to credit from formal financial institutions (ILO 1998; Quisumbing and Pandolfelli 2010). To overcome this limitations, women in many parts of Africa have devised other innovative means of getting credit such as joining informal saving clubs popularly known as ‘merry go round’ or ‘chama’ in Kenya (Kiptot 2007) or ‘tontines’ in Senegal (Guerin 2006). Unfortunately these clubs may not provide them with enough capital to start big income generating projects. Kabeer (2005) and Quisumbing and Pandolfelli (2010) caution that access to financial credit alone may not be enough if women invest in micro-enterprises that have low returns.

Labour

Labour is the only resource that women in many parts of Africa have at their disposal. However, they are disadvantaged in that they face greater difficulty obtaining male labour needed for particular tasks such as land preparation and tree pruning (Swinkels et al. 2002). In Benin for instance, women rice farmers have difficulties cultivating their fields on time and transporting their paddy to storage rooms after harvest due to discrimination in access to a motor-cultivator driver. This leads to late planting and harvesting consequently leading to significant yield losses (Kinkingninhoun-Mêdagbè et al. 2010). In many parts of Africa, men have claim over women’s labour, but women do not have similar claim over men’s labour. For example, females in male headed households in Benin are obligated to work in men controlled fields which take precedence over their own (Abbas 1997). Another similar problem faced by women is their difficulty in obtaining sufficient labour during peak labour activities (Swinkels et al. 2002). Peak season labour periods vary by farming system but the times of land preparation and weeding are commonly the most acute. Not only are women unable to obtain needed male labour; they are also unable to hire labour because of cash shortage. Further exacerbating their crop performance and well-being, peak season periods often coincide with periods of acute food shortages, when women are weakest and may have to work as labourers on others’ farms in order to feed their families. Their inability to mobilize labour for managing their farms in an optimal fashion often puts them on a downward cycle of poor yields, inadequate resources for managing their farms, and further reductions in yields.

Education and extension visits

The uptake of new technologies is often influenced by farmers’ contact with extension services. Several studies have shown that women have lower access to agricultural extension than men. In Malawi for instance, 19% of women had access to extension compared to 81% of men (Gilbert et al. 2002). In Uganda, women had 1.13 contacts with extension compared to men’s 2.03 (Katungi et al. 2008). Figures released by UNEP/GRID-Arendal (2008) show that although 70% of agricultural work in Benin and Zimbabwe is carried out by women, there are less than 10% female extension staff. In addition, most of the extension services are focused on cash crops (men’s crops) rather than food and subsistence crops, which are considered to be women’s domain. These statistics are confirmed by a study carried out in 1998 by CIMMYT and reported by Morris and Doss (1999) on how gender affects the adoption of innovations in Ghana, they found that on average, women reported fewer contacts with extension agents, and a large proportion of women reported no extension contacts at all.

Lack of appropriate technology

Most women in sub Saharan Africa undertake their activities manually due to lack of suitable household, farm and processing technology. For instance, women in Burkina Faso use 3–4 days to prepare P. biglobasa fermented seeds while extraction of shea nut butter is a physically strenuous and time consuming exercise (Teklehaimanot 2004). Technologies to improve crop production are also limited for women farmers. The use of animal traction in known to substantially reduce the demand for women’s labour yet most of them lack access to this valuable technology. In Zambia, the use of a plough to weed, a task performed by women, can be performed six times faster (Allen 1984).

Customs/taboos

Cultural beliefs have strong influence on agroforestry adoption. They include ritual prohibitions against planting or using certain trees, regulations on where trees may be planted, limitations on who may plant trees and legislation set by national government. It is difficult to make any generalization about cultural norms and customary rulings because they vary for different people in different areas. They are however, powerful determinants of peoples’ actions, and often hold more local influence than rules and legislation set by national government. In western Kenya, tree planting activities are dominated by men and the concept of tree owners has been effectively sustained through well manipulated cultural practices (taboos) resulting in fewer women than men participating in tree activities (Chavangi 1994). Taboos advanced in western Kenya are that if a woman plants a tree, she would become barren or her husband would die.

Among the Ibo of south-eastern Nigeria, Nwonwu (1996) reports that women are not allowed to climb certain types of trees such as the oil palm, coconut palm or raffia palm. It is regarded as an abomination if they did so. These taboos and prohibitions were too much of a risk for many women in the past but with modernization and Christianity taking root in addition to a high rate of male migration, women are increasingly going against taboos and planting trees. Ipara (1993) reports that of the 25% of women who braved and planted trees in western Kenya, none reported receiving any repercussions.

Agroforestry technologies

This section presents background information about agroforestry technologies assessed in this paper. The technologies are grouped according to the products and services they generate. The first two groups, improving milk production and soil fertility, mostly involve agroforestry technologies introduced over the last 20 years and are focused on east and southern Africa. Indigenous fruit and vegetable production and processing involve mostly traditional practices and include examples from throughout sub-Saharan Africa. The last set, woodlots for producing fuel and construction wood, involves examples from east and southern Africa. The technologies were selected because information was available on gender issues. Little or no information was available for other agroforestry technologies and products e.g., for medicines, for gums and resins, or for exotic fruits. Findings are categorized by technology because most studies dealt with a particular technology. But in reality, the concept of technology is sometimes not clear, as when a particular agroforestry arrangement has multiple products. For example, a particular tree’s leafy biomass may provide fodder and soil fertility and its woody biomass may provide fuelwood.

Use of fodder shrubs to boost milk production

Most livestock in Africa are found in mixed smallholder farms characterized by their small size, limited production resources and low income levels. The shortage of fodder coupled with the low quality of feed is the greatest constraint to improving livestock productivity and reproductive performance, especially during the dry season (Winrock International 1992). Despite demonstrated advantage of the use of herbaceous legumes as high quality fodder, their use has not been widely adopted by small-scale farmers. The low adoption has been partly attributed to the scarcity and high cost of the legume seed (Paterson et al. 1998). In contrast, there has been considerable adoption of fodder shrubs in the highlands of East Africa to provide the much-needed protein to dairy cows (Franzel and Wambugu 2007; Wambugu et al. 2011). ICRAF and a range of national research and development partners in Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, and Tanzania developed fodder shrub practices in the 1990s. The shrubs are easy to grow, are capable of withstanding repeated pruning and compete very little with food crops. The plants mature in 9–12 months and are then ready to be cut periodically and fed to cows and goats. The shrubs are grown in hedges along boundaries and pathways or in lines to form terraces, thus reducing erosion and providing firewood. Calliandra calothyrsus is the most commonly grown species.

Soil fertility improvement

One of the most serious constraints to the sustainability of agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa is declining soil fertility. In the past, African farmers managed soil fertility on their farms by fallowing their land. As population increased, fallowing of land declined, with many farmers adopting intensified land use practices that required fertilizers to replenish nutrients. Many African states subsidised fertilizer prices to stimulate fertilizer application, but these subsidies were later removed. The removal of such subsidies, due to structural adjustment policies (SAPs), has substantially increased costs for many farmers who now cannot afford fertilizers (FAO 2001). This has exacerbated the problem of declining soil fertility, leading to reduced crop productivity (Sanchez et al. 1997).

To address these challenges, scientists have in the past two decades experimented on low cost agroforestry options for soil fertility replenishment. Three of the most promising options are the use of improved tree fallows, biomass transfer and mixed intercropping (Niang et al. 1996; Sanchez et al. 1997; Ajayi et al. 2001; Thangata and Alavalapati 2003; Kiptot 2008). Improved tree fallows are the deliberate planting of fast growing leguminous trees or shrubs in rotation with crops. Biomass transfer is a technology where biomass from shrubs/trees grown on or off the farm, is cut and incorporated in the soil as green manure when planting crops. Mixed intercropping involves planting nitrogen-fixing trees that can tolerate continuous and heavy pruning, in a regular pattern with crops such as maize. By providing nutrients to crops, these technologies can potentially help farmers improve their soils and incomes, thereby improving food security.

Indigenous fruit and vegetable production and processing

Food insecurity, poverty and malnutrition are some of the major challenges that face sub-Saharan Africa. In Nigeria for example, 70% of the population lives below the poverty line (Bird and Dickson 2005), while in Cameroon the figure is 40%, rising to 55% in the forest region (Schreckenberg et al. 2006). In addition to poverty, Africa is facing a serious problem of not being able to feed its people (FAO 2006). As a matter of fact, it is estimated that 60–80% of rural households in Malawi, Zambia and Mozambique run out of food for as long as 3–4 months per year (Akinnifesi et al. 2004). Those most at risk are women and children. Through the ages, most of these people have relied on wild plants for food during periods of famine. In addition, they provide other products such as medicine, spices, and livestock feed. In a survey conducted in Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe, 26–50% of households confirmed to have reduced vulnerability by collecting indigenous fruits from wild plants (Akinnifesi et al. 2006).

Several studies have acknowledged the fact that indigenous fruits are rich in nutrients in addition to having the potential to generate income to many rural households. In Zimbabwe, for example, wild fruit trees represent about 20% of the total woodland resource use by rural households (Campbell et al. 1997) with women and children being the main beneficiaries. They collect, consume in both fresh and processed form, sell and use the proceeds to buy food and other household goods (Ramathani 2002). In west and central Africa region, indigenous fruits are important components of local diets; Dacryodes edulis, for example is a staple food for 3–4 months of the year with palm oil being the main cooking fat. As one moves to the Sahel, it is replaced by shea butter (Schreckenberg et al. 2006). The shea tree not only provides edible fruits and nuts to make butter but also fodder for livestock. In eastern Africa, households in dry areas consume indigenous fruits such as shea, tamarind (Tamarindus indica), Vitex doniana, baobab (Adanisonia digitata) (Muok et al. 2001; Matig and Chikamai 2009). Despite the importance of indigenous fruit trees in the livelihoods of rural people in Africa, they are seldom planted by farmers, because they are perceived as nature’s gifts. Massive deforestation is reducing the availability of these valuable resources. In view of this, ICRAF and its national partners have in the past decade been undertaking research aimed at domesticating priority fruit tree species in west, eastern and southern Africa to enhance the potential of these trees for increasing the income and food security of rural people. Tremendous progress has been made with domestication efforts in southern Africa focusing on species such Sclerocarya birrea, Uapaca kirkiana, Strychnos cocculoides, Vangueria infausta, Parinari curatellifolia, Ziziphus mauritania, baobab, Syzigium cordum and Vitex spp. (Akinnifesi et al. 2006). In west and central Africa, focus has been on species such as shea, P. biglobosa, D. edulis, I. gabonensis and Garcinia kola (Ayuk et al. 1999a, b, c; Leakey et al. 2004; Degrande et al. 2006). In eastern Africa, priority has been given to shea, tamarind, V. doniana and baobab (Muok et al. 2001; Okullo et al. 2003; Matig and Chikamai 2009).

Woodlot technology

Many countries in Africa are presently facing severe shortages of fuelwood, poles for construction and many other forest products due to increasing human and livestock populations that have led to massive deforestation and land degradation. In Kenya, for instance, the area under plantation forests is expected to decrease from 164,000 to 80,000 ha by the year 2020 (KEFRI 1999). It is further estimated that if the current utilization and demographic factors remain unchanged, then the demand of wood and non-wood forest products is going to outstrip the supply by very big margins. This deficit is likely to manifest itself mainly in fuelwood, a burden that will be borne by women. To overcome this problem, many development agencies in sub-Saharan Africa have been promoting planting of woodlots, an agroforestry technology which aims at improving fuelwood supply and poles to rural communities, income generation and alleviating environmental degradation.

A woodlot refers to planting of trees in sole stands on farm to provide wood for fuel and construction poles (Otsyina et al. 1999). For the past two decades, woodlots have been promoted in rural areas of Africa as a means of improving woodfuel supply and poles in rural communities. A number of countries such as South Africa (Ham 2000), Tanzania (Shanks 1990) and Ethiopia (Jagger and Pender 2005) initially promoted communal woodlots, but due to labour constraints and lack of autonomy many farmers prefer individual woodlots planted on their own parcels of land. In recent years, many non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have been encouraging farmers to plant woodlots through agroforestry so that they can be self sufficient in wood product requirements. Modifications of the woodlot technology include trees along farm boundaries or intercropping with other tree crops.

In Kenya, planting of woodlots is widespread in high potential areas of western, central and eastern Kenya. Species commonly planted in western Kenya are Eucalyptus spp. and M. lutea. At the coastal region of Kenya, the species mainly planted in woodlots is Casuarina equstifolia. In western Uganda species commonly planted are Senna spectabilis, M. lutea, Eucalyptus spp. and Melia azederach (Buyinza and Wambede 2008). In Malawi, common species are S. spectabilis and Eucalyptus (Chikoko 2002). In Tanzania, woodlots are common in Tabora and Shinyanga regions; common species are the Australian acacias such as A. crassicarpa, A. jurifera, A. leptocarpa and A. auriculiformis (Nyadzi et al. 2003).

Women’s participation in agroforestry

In the introduction, it has been argued that agroforestry has the potential to offer great benefits to women. However, their participation is hampered by limited access to resources and other constraints discussed in “Areas in which women are disadvantaged” section. A key finding of this paper is that despite the limitations mentioned in “Areas in which women are disadvantaged” section, women are increasingly exercising their user rights to land and tree resources, and are participating in agroforestry related activities across Africa. Four questions were formulated to evaluate women’s participation in agroforestry in relation to men:

-

1.

What is the proportion of women participating in agroforestry?

-

2.

Are women able to manage agroforestry technologies, that is carry out the needed operations?

-

3.

Do women benefit from agroforestry and how?

-

4.

Do women have access to agroforestry information?

These questions are examined by the technologies discussed in the previous section.

What is the proportion of women participating in agroforestry?

In a study on the achievements and impact of a fodder project in the central highlands of Kenya, Wambugu et al. (2001) found that out of 2,600 group members involved in establishing fodder shrub nurseries, 60% were women. FHHs accounted for 15% of all planting households which is only slightly lower than the proportion of female headed households (18%) in central Kenya (Kimenye 1998). The high participation of women was facilitated by project extension staff, who targeted women’s groups or groups with mostly women members.

On soil fertility management, a review of 10 studies (Table 2) undertaken in Kenya, Zambia, Uganda and Malawi on factors likely to affect the adoption of improved fallows, biomass transfer and mixed intercropping technologies showed that in all except two studies, gender was not a significant variable affecting the use of soil fertility technologies. These findings are consistent with most reviews in the literature on gender differences in agricultural production. For example, Quisumbing (1996) review on male–female differences in agricultural productivity found that most studies on differences in technical efficiency between male and female farm managers showed insignificant differences. That is female farmers are equally efficient as male farmers if individual characteristics and input levels are controlled. In another review of several studies on gender differences in non-land agricultural inputs, Peterman et al. (2010) found that most of them did not find gender a significant variable influencing the adoption of inputs such as inorganic fertilizer and improved seed.

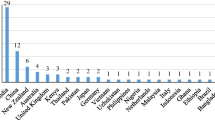

In western Kenya though, Place et al. (2004) reported that women used improved fallows and biomass transfer technologies more than men, who more often used fertilizer (Fig. 1). In Zambia, Phiri et al. (2004) showed that there were no significant differences between proportions of men and women household heads practising the use of improved fallows nor were there any significant differences between single women and female heads of households who were married even though single women are often disadvantaged when compared to female heads whose husbands work away from home. Surprisingly, Peterson (1999) found a higher proportion of single females planting improved fallows than married females; the latter probably needed permission from their husbands who may have prevented them from testing improved fallows.

Use of soil fertility management options by gender of household head, western Kenya. Source: Place et al. (2004)

Phiri et al. (2004) found that in four Zambian villages, 32% of males and 23% of females planted improved fallows. There was considerable variation within villages with one having more females than males planting improved fallows. According to Phiri et al. (2004) this variation could be attributed to the presence of active women’s groups. These findings suggest that the use of improved fallows for replenishing soil fertility is gender neutral; women farmers are as actively involved as their male counterparts. However, women in Zambia had smaller plots than men, 332 m2 as compared to 679 m2 for men. Since the same percentage of males and females stated that they had obtained enough planting material, it appears that females wanted smaller plots than males (Franzel et al. 2002b). This may be attributed to the heavy workload that women bear, land constraints or risk aversion (Franzel et al. 2002b; Keil et al. 2005).

In contrast to fodder production and soil fertility management, women’s participation in indigenous fruit and vegetable enterprises is much greater because indigenous fruits in sub-Saharan Africa are considered a domain for women and children (Campbell 1987). A probable explanation for this perception is that markets for these products are not well developed, and therefore they are considered subsistence by men. But there are also concerns in the literature that as these products become more of a cash crop, the benefits may shift from women to men (Poulton and Poole 2001).

Since fruits are considered a women’s domain, men in Mali maintain shea trees in the cropland because they are a key source of income for their wives. In the shea growing region of Benin, Schreckenberg (2004) found out that 90% of women were involved in collecting nuts/fruits of the shea tree. Other tree products that are frequently collected by women and children in west and central Africa are: P. biglobosa, D. edulis, I. gabonensis and Ricinodendron heudelotii. In southern Africa, common species collected by women are: S. birrea, U. kirkiana, V. infausta, Azanza garkeana, Z. mauritania and S. cocculoides. In eastern Africa, common species are shea, tamarind, V. doniana and baobab. Other studies that have reported similar findings of women and children being the main collectors are Kalaba et al. (2009) in Zambia, Campbell (1987) in Zimbabwe and Ruiz-Perez et al. (1997) in selected areas of eastern and southern Africa.

In Benin, household heads normally reserve nuts of the shea tree for their female relatives. When the fruits are in season, women start collecting shea fruits from common parklands where competition from other women is stiffer. This is normally done on their way to and from the agricultural fields. In a day, women collect head loads of up to 47 kg. When the shea fruits from the common parklands have been exhausted, women turn to their husbands’ field to collect the shea fruits. In Cameroon, a study of gender and commercialization of Gnetum africanum by Kanmegne et al. (2007) found that women and children are the main collectors of the leaves, which are used as a vegetable. They accounted for 80% of the collectors while men accounted for less than 5% of collectors. Men considered G. africanum activities, and especially collection, to be time consuming and unrewarding compared to cocoa, a traditional source of income for men. And the fact that G. africanum income comes in at a time when cocoa is harvested renders it unattractive to men.

Apart from collecting fruits, women are also involved in processing in order to add value to fruit tree products. For instance, in Benin, shea kernels are processed into local butter. This process is very laborious and not a very profitable business and as a result, very few women are involved. In some parts of Benin such as Bassila area, women who make butter, also make traditional soap from left over and rancid butter. This soap is sold locally and it is said to have skin healing properties (Schreckenberg 2004). In southern Africa, products that women process from indigenous fruits/nuts are alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages, confectionaries, additives for other foods, dried whole fruits, oil and butter (Kadzere et al. 2001).

In addition to soil fertility management, fodder production, indigenous fruits and vegetable production and processing, women are also involved in establishment and management of woodlots. In a study by Chikoko (2002), on the analysis of household-owned woodlots between female-headed and male-headed households in Malawi, she noted that most women (96%) in FHHs individually owned the woodlots. Most (61%) women in male-headed households stated that the woodlot is co-owned with the husband, 30% said the husband owns the woodlot and 8% said they owned the woodlot independently. When the same question was posed to men in male-headed households, 73% of them said they owned the woodlot individually while only 27% of the men said they co-owned with their wives. As pertains to the number of trees, female headed households had an average of 840 trees compared to 1,666 for male headed households, reflecting the fact that female headed households’ farms were half as large (2.7 acres compared to 5.5 acres for male-headed households). This confirms data in the literature that women who have adopted agroforestry technologies often have smaller areas and fewer trees (Keil et al. 2005; Schreckenberg et al. 2002; Wanyoike 2001).

Are women able to manage agroforestry technologies?

Although men and women are both involved in management of trees planted on farms, the literature confirms the fact that women do most of the work, especially at the initial stages of tree establishment. In studies conducted by Epaphra (2001) in Tanzania and Gerhardt and Nemarundwe (2006) in Zimbabwe, it was noted that over 60% of women in Tanzania are responsible for managing tree species planted on farms while over 80% in Zimbabwe are responsible for watering young seedlings. This trend is confirmed by Franzel et al. (2002a) in a study undertaken in Embu, Kenya to determine early stages of adoption of calliandra fodder in the central highlands of Kenya. It was found that although 91% of households using calliandra fodder were male headed, in 89% of these households females were responsible for managing calliandra. A similar scenario was observed in Uganda by Nyeko et al. (2004) whereby in over 80% of households with calliandra, women were involved in management. It is interesting to note that husbands who managed their farms in Uganda did so jointly with their wives. In another study by Wanyoike (2001) on management and adoption of calliandra by gender, it was noted that farms managed jointly by men and women had many more trees than those managed solely by men or women, perhaps because the jointly managed farms had access to pooled labour provided by both spouses (Table 3).

Comparing tree survival rates between men and women is one indicator of the degree to which the genders are differentially able to manage tree technologies. The results of such analyses are mixed. In Kenya, male-headed households had somewhat higher survival rates for fodder shrubs than women (45% as compared to 31%) but the differences were highly variable and not significant (S. Franzel pers. comm.). Possible reasons for low survival rates could have been because less labour was available for maintaining the seedlings or a lack of knowledge about how to maintain them. In eastern Zambia, survey data on S. sesban supports the hypothesis that women are able to manage improved fallows as well as men. In farmer-designed, farmer-managed trials planted in 1995/96, half of the participants were women and they had somewhat higher survival rates for Sesbania than men. For example, 47% of women but only 29% of men had survival rates for Sesbania of over 75%, 6 months after planting. For Tephrosia vogelii, men had somewhat higher survival rates. Men and women reported similar problems with similar frequency and did not differ in the number of times they weeded their trees (Franzel et al. 2002b).

How do women benefit from agroforestry?

Women’s rights to tree products are usually limited to products that are considered to have little or no commercial value. These products are mainly indigenous fruits and vegetables, fodder and mulch. KWAP (1996) reported that while only men had the right to harvest all trees, over 50% of women had the right to use S. sesban. This is because Sesbania only provides green manure and fuelwood, products that are not considered to be important to men. Although calliandra as a fodder has been shown to be profitable to farmers, no studies in the literature have been found that show the direct benefits in economic terms that accrue to women. An economic study undertaken in several sites in Kenya and Uganda showed that beginning in the second year after planting 500 calliandra shrubs, a farmer’s net income increases by about US$ 101–122 a year by substituting dairy meal with calliandra. On the other hand, if a farmer uses calliandra fodder shrubs as a supplement for dairy meal, the farmer’s income increases by about US$ 62–115 a year. This is about 5–10% of the total income from the farm. The study did not, however, look at how much women receive from the sale of milk or what percentage of women have access to the income from the sale of milk. The cash farmers save by using calliandra as a high protein feed supplement to their livestock instead of having to purchase dairy meal accounts for 46% of the cost of the cattle enterprise in the central Kenya farming system (Muriithi and Franzel 2001). The funds generated are used to pay school fees and general household improvements. In addition to boosting milk production, other benefits from fodder shrubs include improved animal health, fuelwood which is a direct benefit to women, improved nutrition of the family, seedling sales, high quality manure, bee forage and stakes for vegetable production in addition to environmental benefits such soil erosion control (Franzel and Wambugu 2007). It is reasonable to assume women share in some of these benefits, particularly the non-financial ones e.g., access to home grown fodder and availability of firewood from the prunings frees up women’s labour for other productive enterprises. A detailed study is needed to quantify the actual benefits in monetary terms that women get by using calliandra on farms.

Low cost agroforestry technologies for replenishing soil fertility are attractive to women farmers because they involve low inputs but high returns. Apart from the obvious benefit of improving soil fertility, reflected in the high maize yields, they also provide fuelwood and reduce the incidence of weeds such as Striga hermonthica. Although a review of literature does not give the direct benefits that accrue to women farmers in financial terms, it appears likely, from the results of focus group interviews with Zambian women, that women do benefit (Peterson 1999). An economic analysis undertaken by Franzel et al. (2002b) shows that agroforestry based soil fertility management options are more profitable than current farmer’s practices despite forfeiting two seasons of cropping. Provision of fuelwood from improved fallows is a benefit to women farmers as it reduces their burden of having to travel long distances in search of it. Various studies in Kenya, Uganda and Zambia have shown that improved fallows do indeed generate considerable amounts of fuelwood with the amount varying depending on the species. For instance, 5–42 t/ha was generated within duration of 1–3 years in western Kenya (Swinkels et al. 1997); 24–27 t/ha after 2 years in southwestern Uganda (Siriri and Rausen 2003); 10 t/ha after 2 years in eastern Zambia (Sanchez 1995) and 13.7–21.7 t/ha after 2.7 years in coastal Kenya (Jama and Getahun 1991).

In another study undertaken by Jama et al. (2008) to determine fuelwood production potential from short rotation improved fallows in western Kenya, the results were remarkable. If a farmer planted 0.01–0.08 ha (typical size of land planted to improved fallows in the region), fuelwood harvested would last a typical household between 11.8 and 124.8 days depending on the species and fallow duration. This would increase to 268.7 and 1173.7 days if farmers increased the area planted to 0.25 ha. Mugo (1999) estimates that women who collect fuelwood for cooking far away from the farm spend on average 130 h per year, as compared to only 36 h spent by those who harvest firewood from their own farms. The implication for this is that the time saved by having an on farm wood supply can be diverted to other productive chores such as weeding, planting food crops, processing, food preparation and income generating activities. Women farmers who are practicing improved fallows are therefore benefiting tremendously from the fuelwood collected which is considered a secondary product. Fuelwood in western Kenya, one of the most densely populated areas in Africa, is so scarce that a majority of households use crop residues and cow dung for cooking, resources which would normally have been ploughed back to the farm to increase crop productivity (Mugo 1999).

In contrast to other agroforestry products, women receive substantial financial benefits from indigenous fruits and vegetables (Table 4). A study by Crélerot (1995) recorded earnings from kernel sales as US$ 15–35 per annum in southwestern Burkina Faso which represented 20-60% of women’s income in rural areas. In a study of the contribution of the shea tree to local livelihoods in Benin, Schreckenberg (2004) found out that the shea tree, provided only 2.8% of household income. The income may seem small but it is significant to women in Benin because they are able to control it, is a source of lump sum income, obtained with no investment other than labour. According to a study by Boffa et al. (1996), 66% of women interviewed controlled income from shea production, while 27% shared the control with their family members with a paltry 7% being controlled by the head of household. According to Schreckenberg (2004), income from kernel sales in Benin varied from US$ 7–36 per annum, which for many women was sufficient to cover a substantial part of their annual expenditure.

Other fruit tree species that contribute significantly to the total household income in west Africa include P. biglobosa, D. edulis, R. heudelotti and I. gabonensis. P. biglobosa fruit known as néré in French is highly commercialized in Burkina Faso with women solely responsible for the sale of fermented seeds. The revenue earned according to Teklehaimanot (2004) is about US$ 39 per household accounting for 28.8% of the total income per annum while in Cote d’ Ivoire, neré accounted for 4% of the total household revenue compared with 2% from the shea tree. In Cameroon, farm level production of D. edulis fruits (safou) ranges from US$ 80 to 160 per collector with about 41% sold with the rest being for household consumption (Ayuk et al. 1999a). Both men and women earn cash from D. edulis sales. Fondoun and Tiki-Manga (2000) report an even higher average annual production per household at US$ 555.23. The level of production for R. heudelotti, an important woman’s crop, is estimated at US$ 97 per annum while I. gabonensis fruits and kernels, sold by both men and women, are estimated at US$ 56 and US$ 101 per annum respectively (Ayuk et al. 1999b, c). A combination of these makes a substantial contribution to women’s income. Income from G. africanum is quite substantial with annual average revenue of US$ 2,629 per household in Cameroon (Fondoun and Tiki-Manga 2000). The fact that G. africanum is collected throughout the year gives women a constant supply of cash.

In addition to income from the sale of fruits, nuts, butter, a substantial proportion of indigenous fruit products is also consumed by households. For example, 59% of D. edulis is consumed by the household (Ayuk et al. 1999c). Shea butter is a major ingredient in most kitchens in semi-arid west Africa while I. gabonensis kernels are used as an essential sauce ingredient in southern Cameroon. The fermented seeds of néré are ground into a pungent nutritious spice normally added to soups and stews throughout west Africa. The pulp is used to make drinks; the green pods are eaten as a vegetable during the dry season and are also used for medicinal purposes (Teklehaimanot 2004).

In Tabora Region of Tanzania, indigenous fruits are consumed in large quantities with 44% of farmers getting it from natural forests while 36% buy from the market (Oduol et al. 2006). Women participating in a collaborative project managed by the Tumbi Agricultural Research and Training Institute (ARI-Tumbi), ICRAF, the Tanzanian Women Leaders in Agriculture and Environment (TAWLAE) and the Small Industries Development Organization are generating income through processing and selling of jam, wine and juice. They are earning between US$ 12 and US$ 30 per week through sales of juice. Selling of wine gives them an average of US$ 13 per week (Oduol et al. 2006).

In addition to benefiting from the sale of indigenous fruits and vegetables, having an on-farm supply of wood products is beneficial to women in many ways. In Tabora region of Tanzania, farmers appreciated the fact that they get wood for construction and fuelwood for domestic use and tobacco curing, while others noted that the leguminous trees improve soil fertility (Oduol et al. 2006). Farmers with woodlots save 15–180 min of the whole day they used to get the same quantity of wood. Another study undertaken by Chikoko (2002) in Malawi on the perceived benefits of woodlots by gender showed both women and men received multiple products from woodlots with no significant difference between male-headed and FHHs. However, the difference in total income per household in a year from sale of woodlot products between households along gender lines showed that male headed households earned over three times as much income from the sale of woodlot products as did female headed households. This difference according to Chikoko (2002) may be attributed in part to the number of trees in a woodlot. Female-headed households on average had half as many trees but only 30% as much income as men and therefore may not have had enough trees to meet household fuelwood needs. Another explanation could be that men in male-headed households are attracted to woodlots because of the commercial aspect and would therefore sell the products regardless of the household fuelwood situation. This aspect requires further investigation.

Agroforestry product markets: are women involved?

Another way of assessing benefits is looking at agroforestry product markets. Many studies have reported that women are often involved in marketing agroforestry products, particularly those that are considered a domain for women and children such as indigenous fruits, spices and vegetables. However, their involvement is mostly confined to the small retail trade. In a study of production and marketing of safou in Cameroon, Awono et al. (2002) noted that women dominate the collection of the fruit and are responsible for taking it to the market, where they dominate the retail trade (95% of retailers are women). Men, on the other hand, account for 71% of wholesale traders. This gender difference is confirmed by Schreckenberg (2004) who found that women in Benin also dominated the retail trade of the shea kernels and shea butter. In Cameroon, Kanmegne et al. (2007) found out that in the trading of G. africanum, 93% of retailers were women. The few men involved dominated the wholesale trade as it requires significant capital which men can obtain after selling cocoa. In addition, wholesale trade involves less market time but often a lot of travel which many women cannot undertake due to household responsibilities. But even where women are involved in production and collection of agroforestry products, their involvement in marketing may be limited by the mode of transport used. For example, in Tanga Tanzania, where farmers collect calliandra leaves for processing into leaf meal, 11 of 17 collectors were women whereas 10 of 11 traders were men. Bicycles were usually required for trading but were not considered culturally acceptable for women (Franzel et al. 2007).

A further analysis of marketing of safou, revealed that women traders received lower marketing margins per sack than men: US$ 6 for women against US$ 7 for men (Awono et al. 2002). This may be because men sell more sacks per transaction than women. Most women traders do not have enough capital to increase their stocks of safou. Furthermore, examining the relationship between marketing margins and level of education showed that the highly educated traders are more successful. Given that women’s literacy level is lower than men, they are relatively disadvantaged. Traders who are highly educated have access to better market information (marketing channels and prices) and are therefore in a better position to make informed decisions on where to purchase and dispose of stocks without making any losses. Since women involved in marketing of agroforestry products are confined to retailing, they fail to benefit equitably from the growing national and international markets.

Do women have access to agroforestry information?

Empirical evidence since the 1990s has documented gender disparities in access to agricultural information (Saito and Wildermann 1990; Quisumbing 1996; Katungi et al. 2008; Meinzen-Dick et al. 2010; Peterman et al. 2010). Access to agroforestry information is no exception; fewer women than men are reached. In a study to determine the effectiveness of various dissemination methods in reaching men and women farmers to advise them about managing calliandra fodder shrubs on farms in central Kenya, Wanyoike (2001) noted that fewer women than men had received at least one extension visit. When farms were categorized by the gender of the manager, Wanyoike (2001) found that about 10% of joint managed farms and male managed farms had received at least one visit compared to only 5% of female managed farms. This is a further confirmation that delivery of extension information is biased against women. This bias against women has been attributed to several factors. First, socio-cultural barriers inhibit extension agents, 80–95% of whom are men, from communicating with female farmers (UNEP/GRID-Arendal 2008). Second, there is a general perception that since men are the decision makers, then any extension message should be passed to them (Saito and Wildermann 1990; Meinzen-Dick et al. 2010). This latter assumption has been shown by Abbas (1997) and Gladwin et al. (2001) to be flawed. This is because households are complex institutions with different roles and responsibilities and members may have separate spheres of decision-making with reference to production, income and expenditures. Third is the perception in some places, surprising though it may seem, that women are not farmers (Meinzen-Dick et al. 2010).

For the few women who are able to access extension information, Saito and Wildermann (1990) report that some of them lack basic education and therefore their ability to access and use technical information is compromised. Basic education places farmers in a better position to perceive potential benefits of adopting new innovations. Women’s literacy levels as a proportion of men’s levels are increasing, reaching 63% in west and central Africa over the period 2000–2004 and 85% in east and southern Africa (UNESCO 2007). However, women’s literacy levels are still low: Benin (48%), Cameroon (36%), Tanzania (33%) and Zimbabwe (15%) (UNESCO 2002). This has implications on the adoption of agroforestry innovations. But the lack of education does not necessarily prevent farmers from adopting new practices. In Embu district of Kenya, Wanyoike (2001) noted that women who were using calliandra fodder shrubs had lower education than men; an average of 7 years of schooling for men and 2 years for women. Wanyoike (2001) found considerable differences in male and female attendance in extension events. For example, a higher proportion of farmers in male-headed households (20%) than in female headed households (8%) had attended field days. This is further confirmed by KWAP (1996) in a survey on gender participation in mass awareness activities in Uasin Gishu district, Kenya, where men participated in about twice as many mass awareness activities as women. According to Wanyoike (2001) men who had not attended cited lack of awareness of the time and venue of the field days as the main reason while women cited lack of time as they are normally involved in household chores all day long.

Recommendations on how to promote women’s participation

This review provides ample evidence that agroforestry has the potential to offer great benefits to women across Africa. While women’s needs vary across locations, they are attracted to agroforestry because of minimal inputs needed, particularly with regard to cash, and the substantial benefits, in terms of food, fuelwood and other products and services that they get, particularly in times of need. Despite the fact that agroforestry is advantageous to women, they face several limitations discussed in “Areas in which women are disadvantaged” section which hinder them from benefiting from agroforestry enterprises. This section proposes various technological, policy and institutional recommendations to promote efficient participation of women in agroforestry with greater benefits accruing to them. We focus on recommendations which affect agroforestry in particular and which are based on research reported in this paper. Beyond the constraints specific to women and agroforestry there are structural problems in agroforestry in the agricultural sector, e.g. low returns and lack of investment that affect both men and women. This section does not address these problems or make recommendations which are more applicable to agriculture in general. For example the need for better market infrastructure is not discussed.

Recommendations will of course need to be location specific and based on the households’ needs and circumstances, which can only be determined after undertaking a gender analysis. Household members will need to be involved in the planning, implementation, and evaluation of the various interventions. Participatory methods for doing this are well documented (Ashby 1990; Gonsalves et al. 2005).

Technological interventions

Domestication of important agroforestry species

Many tree products that benefit women are collected from wild populations in forests, woodlands/rangelands, parklands or on farms. For centuries this has been possible without impacting negatively on the environment. However, increasing population and trade has increased the demand for these products and, through deforestation, reduced their supply. This increasing demand has led to degradation of agroforestry products such as P. biglobosa V. parodoxa and G. africanum in particular. Evidence of degradation has been shown in terms of reduced densities and population structure (Gijsberg et al. 1994; Kelly et al. 2004). In Uganda the parklands are characterized by old trees of V. parodoxa with no regeneration (Okullo et al. (2003). Apart from fruits and kernels, the demand for G. africanum leaves is also very high both locally and internationally. A recent survey on the marketing of G. africanum revealed that 3,600 tons is shipped annually to Nigeria from Cameroon and exported to European countries and the USA (Asaha et al. 2000). In order to meet the demand, women walk several kilometers to search for it. During harvesting, the trees that G. africanum vines grow on are often felled, creating widespread damage. In some cases harvesters uproot the whole vine. The high demand coupled with unsustainable harvesting methods is leading to scarcity of valuable agroforestry tree products.

Promoting participatory domestication initiatives that integrate local and scientific knowledge will facilitate the integration of these valuable species into appropriate farming systems thereby resulting in technologies that are economically, socially and ecologically acceptable. Participatory domestication initiatives led by ICRAF and national partners have seen farmers in west Africa domesticating tree species such as shea, D. edulis, I. gabonensis and P. biglobosa (Lovett and Haq 2000; Schreckenberg et al. 2002; Leakey et al. 2004; Degrande et al. 2006). The end products of these initiatives are appropriate cultivars and propagation methods that meet a range of market, and producer requirements. Market requirements include fruit with desired size, taste and colour. Extending the fruiting periods is also important so that producers, especially rural women, can have a year round flow of cash from agroforestry products. In addition to cultivars that meet market requirements, women need cultivars that are easier to harvest. Women are constrained when it comes to harvesting because most trees are very tall and they therefore have to rely on men to harvest, often at a fee. Those women without assistance end up relying on fallen fruit whose quality is compromised. Cultivars are needed that are of reasonable height so that anyone, even children, can harvest without having to climb a tree. An additional hindrance is the taboos in west Africa that prohibit women from climbing certain trees. Smaller trees have the additional benefits of taking up less land, a resource which is often very limiting for women farmers.

Development of post-harvest storage methods

Many agroforestry products have a very short shelf life, particularly fruits and vegetables, which are mostly collected and marketed by women. Ramathani (2002) and Kadzere et al. (2006) reported that post harvest handling and transport are the major causes of losses of perishable agroforestry products. Karaan et al. (2005) reported that in Zambia collectors and wholesalers attributed the loss of fruits to poor handling 82.9%; rotting 11.4%; heat 2.9% and inappropriate containers 2.9%. For instance, D. edulis lasts only 5 days which makes it very difficult for women to market it and they therefore often dispose of their products at throw away prices to avoid incurring huge losses. It is therefore important to come up with appropriate techniques of improving the post-harvest quality of on-tree and off-tree ripened fruits. In addition, wholesale traders normally store their produce in large heaps on the open ground with no cover to protect from rain, sunshine and wind. The bulk storage affects the quality of the fruit because those at the bottom of the heaps are squashed while those at the top are baked by the sun thereby leading to huge loses. Development of low-cost storage boxes would go along way in helping reduce losses incurred.

Development of appropriate agricultural and processing techniques

The problem of limited shelf life can be addressed through processing which ensures supplies for periods of shortage and can improve product quality. Where there is market demand for such products, marketing of processed products can also increase women’s incomes. Most women still use ancient processing techniques that were passed down to them through generations. For example, Teklehaimanot (2004) reported that 80% of shea butter in Mali and Burkina Faso is made traditionally. Traditional extraction techniques for shea butter are time consuming and physically strenuous; they also require huge amounts of fuelwood and water and have a low extraction efficiency, creating a significant drain on these scarce resources. The preparation of fermented seeds of P. biglobosa in Burkina Faso, compressing leaf meal in Tanzania and extraction of R. heudelotti nuts in Cameroon are other examples where women’s traditional processing methods are laborious. Simple low cost techniques for processing in these cases could help women reduce labour requirements and wastage while improving productivity and maintaining nutritive quality. Tools and practices to help women reduce the time taken and drudgery of tasks will free women’s time, which can otherwise be used in other productive activities such as attending extension sessions. Potential processing techniques need to be screened for their profitability and sustainability. Development of efficient agricultural and processing techniques also needs to be accompanied by capacity building. Women need to develop their business and marketing skills in addition to processing techniques. Key skills needed are; how to assess demand, develop business plans, negotiating skills and record keeping. A key issue is whether training should involve individuals or groups. This depends on the particular situation. Experience from Tabora, Tanzania shows that training groups is more cost efficient (ARI-Tumbi 2006). Furthermore, even when group enterprises fail, capable individuals carry on with the activities using the skills learnt.

Development of new products

Once women can effectively produce raw and processed materials for local markets, they can seek opportunities in developing new products. For women to compete favourably, and also have an edge, they need to move away from the traditional products into a diversity of high-value products such as oil, soap, juices, body lotions, wine, and leaf meal. Such new products need to be carefully assessed however, taking into account projections of risk, profitability, competition, and economies of scale. This diversification can often be done using the same raw materials. For instance, women engaged in calliandra fodder production in the high potential areas of eastern Africa, can also package calliandra leaf meal for sale in Agrovet shops and to other dairy and poultry farmers as a fodder supplement as is already being done in Tanga, Tanzania with Leuceana leucocephala. Producers, who are usually women, collect Leuceana from the wild and then dry and crush the leaves into leaf meal. Next, the meal is packed into bags and sold to owners of stall-fed dairy and poultry enterprises (Franzel et al. 2007). Women in southern and west Africa are already producing various products from indigenous fruits but the range needs to be increased so that they have an edge in marketing. In East Africa, product development from indigenous fruits is still at its infancy and therefore efforts need to be stepped up to empower women to venture in new products which will enable them diversify their incomes.

Policy interventions

An enabling policy environment is critical in making sure that agroforestry benefits women. In order to ensure that women benefit from agroforestry, gender sensitive policies need to be put in place. These are grouped into four key areas; extension services, access to market information, micro finance and land tenure reforms.

Access to extension services

The weakness of many extension systems, particularly public ones, has been widely acknowledged (Davis 2008). Christoplos (2010) notes that complaints against extension concerning gender may be merely ‘shooting the messenger’ because gender bias is grounded in social norms, e.g., discouraging women from becoming extension agents. Moreover, gender biases in extension may be due to wider policy biases, such as those promoting cash crops, which men dominate, and ignoring subsistence crops, which women may benefit most from. To ensure that extension services benefit women, deliberate gender sensitive interventions need to be put in place including;

-

Training more women extension officers, particularly to serve communities that have strong traditions that prohibit male extension officers from interacting with women farmers.

-

Ensuring that at least half of those who participate in any activity are women.

-

Ensuring that extension activities address different interest groups i.e. women are more interested in products such as fruits, fuelwood and vegetables while men are more inclined towards trees for timber and poles.

-

Targeting womens’ enterprises. Women may not be interested in many “cash crops,” because they know they will not control the income generated. Helping women improve incomes from enterprises considered to be in womens’ domains may be of more interest and benefit to them (Christoplos 2010).

-

Targeting women’s groups for assistance. This review has shown the effectiveness of targeting such groups as a means of disseminating information and technology to women.

-

Finding out from women which periods of the season and day they are most free to meet and holding meetings/field days/seminars at these times.

-

Holding separate meetings for men and women.

-

Organizing video show sessions for women who are not able to participate in tours.

Access to market information

The rise of market information systems based on information and communication technologies (ICTs) offers great potential for improving smallholder access and returns. But to our knowledge, none of these organizations have programs specifically targeting market information to women. Some type of public–private partnership is likely required in which a donor or government project subsidizes the targeting of market information services to women. Such a programme might involve subsidizing the provision of handsets to women or specialized training on how to use the service. Knowledge is power and with access to market information, women farmers can greatly reduce losses due to wastage for lack of buyers as they will be able to make informed decisions about when to produce, what to produce, for whom to produce, and when and where to sell their produce. They will also have strengthened bargaining power and save precious time and money as they will only leave their homes when they are sure they have a buyer for their produce.

Improving women’s access to finance from micro-credit institutions

Access to finance from credit institutions is discussed in “Areas in which women are disadvantaged” section as one of areas where women are disadvantaged. According to World Bank (2007), women in developing countries receive less than 10% of available credit. This is mainly due to lack of land title deeds, which are normally used as collateral in rural areas. For women to access financial credit, governments need to intervene to encourage the development of rural micro-credit institutions whose regulations are friendly to women. Intervention can be in the form of accepting other forms of collateral such as machinery, furniture and any other tangible assets that women own. The capacity of existing social organizations such as women groups need to be strengthened so that they may access credit individually but use the group as collateral. A good example of such an innovative approach in Kenya is known as Fanikisha and is being implemented by Equity Bank which partnered with United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO), International Labour Organization (ILO) and Ministry of Finance in 2008. The aim is to increase women’s access to credit. The programme targets women who lack assets that can be used as collateral (UNDP 2010). By accessing credit, women would be in a better position to adopt the use of improved practices and technologies and operate bigger businesses thus increasing their contribution to household income which may consequently improve their decision-making power in households. A study by Ishani (2009) showed that when women contributed to household income, the balance of power shifted, as they had more voice in (joint) decision-making.

Finally, instead of providing free equipment to women’s groups, as many NGOs and projects do, institutions would be better off helping the groups to link to financial institutions and, if necessary, subsidizing the credit that groups receive to purchase the equipment themselves. This approach helps ensure that groups link to financial institutions, that a proper business plan for using the equipment is prepared, and that NGOs and projects will be able to serve more groups since they are only paying a portion of the costs of the equipment (Faulkner et al. 2009). By accessing credit, women would be in a better position to adopt the use of improved practices/technology and operate bigger businesses thus increasing their contribution to household income which may consequently improve their decision making power in households.

Land tenure reforms

As discussed in “Areas in which women are disadvantaged” section, women in Africa customarily have limited rights to land. Moreover, what rights they have may cease to exist upon divorce, widowhood or failure to have a son. In order to protect women, African governments should enact land policy laws that:

-

1.

Require spouses to have joint ownership of land, in order to prevent men who are customarily owners of land from disposing it without their wife’s consent. In the absence of such laws, it should be mandatory for men selling land to have written consent from the spouse.

-

2.

Grant widows the right to their husband’s land.

-

3.

Allow daughters to inherit land from their parents.

These policies, if put in place and enforced, will ensure that women have equal rights to land.

Institutional interventions

Women producers in sub-Saharan Africa are trapped at the production end of the value chain. In order for women to come out of this trap, governments, NGOs and the private sector need to intervene by facilitating women to form and strengthen their groups and associations, linking them up with markets and industry. By engaging in collective action women would be able to gain a more powerful position in the value chain which is advantageous in several ways: stronger bargaining power, bulk sales/purchases of inputs, ensuring a sustainable supply of products, reduction in transaction costs, attract more and larger buyers, access outside resources, such as extension and development assistance, access to the lucrative fair-trade and other certified markets, and above all be able to contribute to the policy formulation process.

Strengthening women’s groups at the community level is critical, as is helping such groups to federate across larger areas. There are several examples in the literature where women have come together and through the facilitation of various institutions, are currently reaping the benefits of agroforestry. In southern Africa, PhytoTrade Africa has been helping southern Africa’s natural products industry to achieve rapid growth while ensuring its long-term sustainability and social equity through product development, market development and supply chain development. In 2006, 30,000 producers in seven southern Africa countries (93% women) sold raw materials to PhytoTrade Africa (PhytoTrade 2007). In Burkina Faso, 400,000 rural Burkinabe women have been working with the UN Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM) and the Centre Canadien d’ étude et de Coopération Internationale (CECI), a Canadian NGO, which has been facilitating them to process and market shea nuts. UNIFEM linked these groups to a French cosmetics company known as ĽOccitane that purchases shea butter directly from the Union des Groupments Kiswendsida (UGK), a network of more than 100 women groups. This ensures that a greater share of the revenue goes to producers who are women instead of middlemen. In addition the company provides training in quality control and pays for the shea butter in advance (Harsch 2001).

Conclusions

This review has shown that that agroforestry has the potential to offer great benefits to women. However, their participation is hampered by socioeconomic, cultural and policy issues that vary across locations. These issues, if addressed, will go along way in ensuring that more women participate in agroforestry with greater benefits accruing to them. Several promising approaches to improving women’s benefits from agroforestry are documented in this paper. For example, while the enterprises in women’s domain are often low-value, there are cases where collective action and marketing interventions have helped raise values and incomes, as with indigenous fruit processing and marketing in Tanzania. Further, while extension services are biased towards men, the targeting of women through women’s groups has helped, in some instances, to raise the proportion of women beneficiaries to about half, as in the case of fodder shrubs in Kenya.

This review was guided by four research questions which were tackled accordingly based on data available. Our coverage was limited to articles published in English, so there was bias towards Anglophone Africa. Moreover the technologies assessed tended to be found, or at least reported on more frequently in east and southern Africa. Another shortcoming was that most subjects could not be addressed adequately due to lack of data. There are few studies on gender and agroforestry and small samples sizes often restrict the possibility of generalizing from them. Research to fill these gaps will enable the scientific community, policy makers and development practitioners to understand more fully the extent to which women across Africa are involved in agroforestry and thereby facilitate the development and implementation of initiatives that take into account gender issues and generate greater benefits for women. Priority research areas for further investigation include;

-

(a)

Measuring actual income women receive from agroforestry, relative to non agroforestry enterprises and also relative to what men earn. It is also important to assess how agroforestry contributes to sustainable livelihoods.

-

(b)

Assessing the effectiveness and impact of alternative dissemination methods on women participation and benefits.

-

(c)

Determining how different categories of women, e.g., female heads of households, women in male-headed households and youth benefit from agroforestry.

-

(d)

Identifying success stories across Africa and assessing the factors that have contributed to their success.

-

(e)