Abstract

This chapter has a threefold aim: (1) to contextualize older persons’ inclusivity at municipal level as outlined in Goal 11 of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and international, African regional and South African law and policy frameworks; (2) to obtain an assessment of service delivery by local government, and (3) to reflect on gaps in service delivery and offer suggestions. Stratified sampling was used and information obtained through semi-structured interviews, emailed responses and focus groups from representatives (n = 17) on three local government levels, NGO representatives (n = 5), and officials from the South African Local Government Association (SALGA) and the Department of Social Development (n = 26). A sample of older persons (n = 302) from a rural area and two large towns in North West and Gauteng provinces completed questionnaires and participated in semi-structured interviews (n = 14) and focus groups (n = 22). Findings indicated compromised service delivery related to local government officials’ systemic, managerial, and capacity challenges. Municipal services were either non-existent or age-inappropriate. Local government’s unresponsiveness leaves older people at risk—particularly those who lack social networks. We present suggestions to address the disconnect between the intent of laws and policies for inclusivity and municipal service delivery, and the service delivery experiences of older persons.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Basic and municipal service delivery

- Developing country

- Information and communication technologies (ICT)

- Law and policy frameworks

- Older persons

- South Africa

To address the precariousness of most South Africans across the life-course, and more specifically of a growing older population, provision of effective and efficient delivery of timely and reliable basic public services is crucial, as too are more specialised interventions for targeted populations. Public service delivery, therefore, is identified as one of the most important ways of reducing poverty and improve socio-economic conditions.

Within the broader ambit of this book—to design and render appropriate services and interventions—it is paramount to understand sociopolitical context (see Chap. 1), the law and policy architecture, and the programmatic dynamics embedded in that context. While much has been published about municipal service delivery deficits in general, little research has been undertaken to interrogate the non-compliance for service delivery based on the law and policy for older persons in South Africa. The inclusion of older persons in service delivery is becoming increasingly topical given the focus in international policy on the notion of inclusivity of older populations across life domains.

Accordingly, this chapter describes and analyses, from international and local perspectives, with specific reference to older persons, the de jure ideals expressed in the law and policy structure that directs South Africa’s municipal service delivery. The de facto experiences of service delivery to older persons are then described and analysed from the points of view of municipal officials across municipalities, and of older persons from a range of settings on the rural–urban continuum. We conclude the chapter with suggestions for including among others the use of technology as a way to enhance inclusive municipal service delivery in accordance with the notion of ‘leaving nobody behind’ (see United Nations 2030 Agenda).

1 Municipal Service Delivery for all Ages

Globally, local government (also referred to as city authorities) is regarded as the organ of state best placed to provide basic services to communities, and to do so in ways that are safe, resilient, sustainable and inclusive. Reddy (2016) describes service delivery by local government as “the provision of municipal goods, benefits, activities, and satisfactions that are deemed public, to enhance the quality of life in local jurisdictions” (p. 2). Quality of life at the municipal level is also a focus of Goal 11 of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), whose first target is access for all to adequate, safe and affordable housing, and basic services by 2030.

The post-1994 democratic developmental South African state opted for a strong local government system, as embodied in Chapter 7 of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 (Constitution, 1996) and subsequent government laws and policies. All the country’s people are legally entitled to local government services, hence this Chapter is embedded in the social contract theoretical framework (Kaplan, 2017; Muggah et al., 2012). This points to the mandate of this level of government to render, maintain, and facilitate services to address basic communal needs as well as to facilitate the social transformation needs of all.

In South Africa, delivery and sustained upkeep of basic municipal services have proved unreliable at times, in some cases failing totally, thereby endangering local communities and compromising their human rights (Stats SA, 2016). Dysfunction in many municipalities assumes different forms: notably, the lack of ethical conduct and political and management will to make sound appointments; failure to act responsively and responsibly on contentious issues; failure to pass municipal budgets; inability to obtain unqualified audits; and, of particular relevance, failure at the local citizen interface to communicate properly with communities and address their needs (Atkinson, 2007; Booysen, 2012; Koma & Modumo, 2016; Kroukamp & Cloete, 2018; World Bank, 2011).

Given South Africa’s Apartheid past, accessibility to basic services relates closely to social inclusion and social capital. It follows that failure by municipalities to deliver services can have a detrimental impact on social and economic development (Stats SA, 2016), and on communities’ perceptions and experience of responsive and responsible local government. Municipal service delivery failures provoked violent and widespread responses, particularly since 2010 (Banjo & Jili, 2013; Johnston & Bernstein, 2007; Stoffels & Du Plessis, 2019). Some residents withheld their municipal rates and taxes (in so-called rates boycotts) as a sign of revolt against poor municipal service delivery (May, 2010).

Against this background, information and communication technologies (ICT) offer promise as a key to citizen-centred municipal service provision. The potential of ICT for development, and the effects of its widespread and increasing diffusion, have been the focus of a range of investigations in emerging economies (Avgerou, 2010; Heeks, 2010; Pozzebon & Diniz, 2012). Studies on this theme are commonly based on the premise that ICT can help to change socio-economic conditions for the better in developing countries (Mann, 2003; Walsham et al., 2007), thereby improving governance in terms of the social contract between society and state (Kanungo & Kanungo, 2004; Kaplan, 2017).

The next section elaborates on South African law and policy architecture relevant to citizen-centred municipal service provision, especially for older persons.

2 A Law and Policy Framework that Protects, Enables, and Directs

At the international, African regional, and national levels legal mechanisms exist that protect vulnerable groups, enable local government action towards inclusivity, and direct the way in which public services (including municipal services) should be rendered, broadly drawing on social contract theory.

2.1 International Policy Calling for Inclusivity at the Local Level

The rights of marginalized groups, including older persons, are fairly well articulated in international and African regional law, policy and multilateral statements. Examples include the 1982 Vienna International Plan of Action on Ageing (UN, 1982), the 1991 United Nations Principles for Older Persons (United Nations General Assembly, 1991), the 2002 Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing (MIPAA) (United Nations, 2002), and the 2003 African Union Policy Framework and Plan of Action on Ageing (AU/HAI, 2003), alongside human rights instruments such as the Universal Declaration on Human Rights (UDHR) (United Nations General Assembly, 1948), the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) (United Nations General Assembly, 1966a), and the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) (United Nations General Assembly, 1966b). The rights and interests of older persons find further protection in African regional instruments such as the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHRP, 1981), the Protocol on the Rights of Women in Africa (AU/HAI, 2003), and the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Older Persons in Africa (AU, 2016). While offering only implicit protection to older persons, the international framework is clear about recognising and safeguarding the rights of everyone in relation to life, human dignity, non-discrimination and bodily integrity. The thinking at international and regional law level seems to be that older persons ought not to be subject to prejudice on the basis of their age, and ought not to be relegated to a marginalized or disadvantaged position in society. This view translates into advocacy for age-based inclusivity in societies worldwide.

The present century has also seen a proliferation of international policies calling for social inclusion, especially at the local level and in relation to public service delivery. Goal 11 of the SDGs focuses on cities or localities and it envisions that, by 2030, there should be “access for all to basic services … inclusive urbanisation and … access to safe, affordable, accessible and sustainable transport systems for all … with special attention to the needs of those in vulnerable situations, women, children, persons with disabilities and older persons”. The New Urban Agenda (United Nations General Assembly, 2016) similarly calls for inclusivity at the local level, and state parties have expressly committed to “fostering healthy societies by promoting access to adequate, inclusive and quality public services”. One of the targets set in Africa’s Vision 2063 (AU, 2015) is further to provide social protection to at least 30% of vulnerable populations, older persons explicitly included. It also makes mention of transformative E-applications and the information revolution to form the basis of service delivery across the African continent. Vision 2063 is clear on achieving capable institutions and transformed leadership at all levels, with a 2023 target of having “70% of the public acknowledge the public service to be professional, efficient, responsive, accountable, impartial and corruption free” (AU, 2015). In similar vein, the African Charter on the Values and Principles of Public Administration (AU, 2011) sets out, as one of its objectives applicable to sub-national governments (municipalities), “to ensure quality and innovative service delivery that meets the requirements of all users” (Art. 2(1)). The emphasis on innovation links to Article 8 of the Charter, which compels authorities to modernize public services through modern technologies. Notably, one of the Charter’s principles posits that public services should adapt to the needs of users (Art. 3(5)) and, further, that an entire section should be devoted to accessing information about service delivery. Explicit provision is made for authorities to establish “effective communication systems and processes to inform the public about service delivery, to enhance access to information by users, as well as to receive their feedback and inputs” (Art. 6(3)). In Africa and elsewhere, increased attention is paid to criteria for rendering basic services by local and other authorities. Service delivery-related duties and the objective of inclusivity are further backed by an encompassing human rights framework.

The body of international law and policy is instructive for South Africa. While much of it is not legally enforceable owing to its ‘soft law’ character, it indicates a zeitgeist that favours the protection of the interests of marginalized groups such as older persons and the related standards that local authorities are expected to reach in delivering services. The country’s 1996 Constitution stipulates that, when interpreting any South African legislation, such as the Local Government: Municipal Systems Act (32 of 2000) (Republic of South Africa, 1998a) and the Local Government: Municipal Structures Act (117 of 1998) (Republic of South Africa, 1998b), “every court must prefer any reasonable interpretation of the legislation that is consistent with international law over any alternative interpretation that is inconsistent with international law”. While the Constitution is silent on the status of international policy such as the SDGs or the New Urban Agenda, the government (including municipalities) may arguably be expected to calibrate its planning, decisions and policies with internationally agreed objectives and ideologies. African regional instruments, such as the African Charter on the Values and Principles of Public Administration (AU, 2011), which South Africa has ratified, carry the force of international law and come with binding obligations and instructions. Some of these reach into the scope of governance of sub-national authorities, including municipalities.

2.2 A South African Law and Policy Framework that Protects the Vulnerable, Enables Action, and Directs those Responsible for Rendering Public Services

South Africa’s 1996 Constitution was drawn up to ensure that, post-Apartheid, all its people, whoever they are, would have their basic rights and interests protected. The Bill of Rights covers rights and provisions that direct how all three government spheres (national, provincial, and local) should deliver public services (see Chapter 2 of the Constitution) (Constitution, 1996). An inclusive reading of the Constitution reveals that (a) the government as a whole is responsible for upholding and protecting the rights of all people in South Africa, and (b) all three spheres have a public administration function, but local government alone is tasked with delivering basic services to local communities. Notably, the Constitution divides authority and responsibility among the three spheres of government within a system of cooperative government. Whereas no single sphere has exclusive responsibility for guarding the interests of older persons, local government’s explicit mandate is to execute municipal service delivery diligently to the advancement of all sectors of society, including older persons in line with the Older Persons Act (13 of 2006) (Republic of South Africa, 2006) and the Policy for Older Persons (Republic of South Africa, 2005).

The country’s constitutional dispensation provides for three categories of municipalities: metropolitan, district, and local. They are referred to collectively as ‘developmental local government’, a post-1996 concept making local government the service delivery arm of national government. Local government has far more autonomy and responsibility than before and is regarded as co-responsible for the socio-economic development and overall well-being of people in South Africa. Chapter 7 of the Constitution outlines the objects, duties, and powers of municipalities. It makes explicit provision for sustainable delivery of services to local communities and for such communities’ involvement in local government matters (s 152 of the Constitution) (Constitution, 1996). Typical basic services that municipalities should render include water services provision, waste removal and solid waste disposal, municipal health services, sanitation services and domestic wastewater and sewage disposal systems (Schedules 4B and 5B of the Constitution). Although the Constitution does not specify categories of intended recipients, municipal services must be rendered within the broader context that older persons, like others, have a constitutionally entrenched right to life, human dignity, privacy, access to sufficient water, access to adequate housing, an environment not detrimental to health or well-being, access to health-care services, access to information held by the state, and the right to just administrative action (i.e. to just and legitimate decisions by authorities) (see Chapter 2 of the Constitution). In other words: the rights of people inform how public services should be rendered. The Constitution further dictates that every municipality must provide democratic, accountable, and responsive government for people in the community, and that it must structure and manage its administration, budgeting, and planning processes to give priority to everyone’s basic needs. For a municipality to respond properly and to determine its people’s basic needs, special engagement with older persons and their specific requirements is necessary.

National legislation also guides the ways in which municipalities should render services to older persons. A basic municipal service is defined in the Systems Act as “a municipal service that is necessary to ensure an acceptable and reasonable quality of life and, if not provided, would endanger public health or safety or the environment”. The Act further stipulates that municipalities should encourage and create conditions for older persons to participate in municipal affairs, including service delivery related decisions and the development and adoption of the Integrated Development Plan (IDP), its compulsory municipal strategic plan. The conditions are not specified but it can be assumed that they would cater for access, safety, and dignity. In addition to participation by older persons through its elected political structures, the municipality must develop and implement other appropriate mechanisms, processes and procedures for community participation, so as to bring about social contract formation. In terms of the Act, municipalities must be guided by what is appropriate for a specific community, with due consideration for new technologies, contemporary channels for mass and individual communication, and novel ways of conveying specific messages. Furthermore, every municipality should further establish appropriate mechanisms, processes and procedures for the receipt, processing and consideration of service delivery complaints, notification of public comment procedures, public meetings, and report-back to the community. The Act dictates that a municipality must take into account the language preferences and usage in the municipality, and the special needs of people who cannot read or write. It is the duty of municipal councils to consult with the local community about the level, quality, range, and impact of municipal services and the available options for service delivery.

Notably, the Act further determines that the administration (officials) of a municipality must establish clear relationships with all community members and provide accurate information about the level and standard of municipal services they are entitled to receive, and must also inform the local community how the municipality is managed. The Systems Act furthermore makes provision for local government instruments including IDPs, which are compulsory municipal strategic plans. These plans (together with spatial and other sectoral plans) are well placed to mainstream the rights and interests of older persons in municipal planning decisions and overall local governance and to direct a municipality’s service delivery priorities for a minimum period of four years.

The Promotion of Administrative Justice Act (3 of 2000) and the Promotion of Access to Information Act (2 of 2000) (Republic of South Africa, 2000) provided national legislation aimed at procedural fairness in dealings with municipalities and the accessibility of information they hold (Republic of South Africa, 2000). Such information would typically include service delivery standards. By virtue of their general application, these two Acts embody in more detail older persons’ constitutional procedural rights (see sections 32 and 33 of the 1996 Constitution). These rights may typically apply when a municipality makes a decision affecting an older person, or when information in the municipality’s possession is needed for an older person to protect his or her rights. Decisions and access to information of this kind are an everyday part of municipal service delivery.

The Intergovernmental Relations Framework Act (13 of 2005) (Republic of South Africa, 2005) elaborates on measures for cooperative government and intergovernmental relations in the business of government. One of the Act’s explicit objectives in its section 4 is to advance “effective provision of services”. It draws on the principles for cooperative government and intergovernmental relations contained in Chapter 3 of the 1996 Constitution and is instructive where there is fragmentation within and across organs of states (such as municipalities). It often happens that lack of information-sharing among departments or the misalignment of budgets and planning across spheres of government (local and provincial) causes substandard service delivery. This situation can be equally frustrating for those tasked to render and those entitled to receive services. Not only can the principles and structures provided for cooperative government help to improve inclusive service delivery in a single municipality, but they can also be useful for inter-municipal peer-learning and for sharing lessons learned concerning delivery of services to older persons, specifically.

A project devoted to improving service delivery to older persons requires detailed understanding of (a) the legally entrenched duties of municipalities with respect to service delivery, and (b) people’s rights. These duties and rights underpin what everyone, including each older person, is entitled to as a resident of their municipality. They remind councils and municipal administrations of their responsibilities in terms of the law. The body of law relating to municipal service delivery finds support in national policy instruments such as the White Paper on Local Government (1998) (Republic of South Africa, 1998c), the National Development Plan Vision 2030 (South African Government, 2012), and the Integrated Urban Development Framework and Implementation Plan (IUDF) (Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs, 2016). The IUDF in particular makes it clear that the design of human settlements and other infrastructure must take into account safety and access to adequate housing for, amongst others, older persons. An inclusive reading of the policies mentioned further suggests that the South African government supports age-friendly cities and towns and urban places that are stable, safe, just and tolerant, embracing diversity, equality of opportunity, and the participation of all people, including the vulnerable. Such urban places would however require access to adequate municipal services and municipal information infrastructure, albeit without people falling trap to a digital divide.

The White Paper on Local Government, adopted shortly after the 1996 Constitution, includes nine overarching and instructive principles for municipal service delivery (Republic of South Africa, 1998c). These, presented in Table 2.1, are meant to guide municipalities in their decision-making. For present purposes it is also important to note that by virtue of their constitutional autonomy, municipalities themselves are law and policy makers. They have the constitutional authority to develop local policies and plans (e.g. spatial development frameworks) and to pass and enforce municipal by-laws. Any of these instruments will form part of the overall law and policy framework with which service delivery in a municipality must align. These instruments and their conceptualisation can also be developed creatively to advance the position of older persons in a municipal area. One example would be the involvement of older persons in the legally prescribed public participation processes that accompany the adoption of a municipality’s IDP or its spatial land-use and management by-law.

This backdrop of international and national law and policy frameworks informs our baseline assessment of the perspectives of government officials involved in, and older recipients of, services delivered.

3 Baseline Assessment of What Transpires in Relation to Service Delivery

Our assessment of service delivery realities focuses on the perspectives of local government officials, followed by those of older service recipients, in three pilot communities ranging from rural to urban.

3.1 Perspectives of Local Government Officials

In 2013, the Community Development Directorate of SALGA commissioned the North-West University (NWU) to research the provision of services to older persons (60 years and older) by local government. SALGA is an association of municipalities whose mandate derives from South Africa’s Constitution. One of SALGA’s main aims is to assist municipalities with policy guidelines for community development. This involves mainstreaming transverse issues pertaining to older persons and children, youth, disability, gender, HIV and AIDS, municipal health services, primary health care, disaster management, safety, and security (South African Local Government Association, 2015).

3.1.1 Method

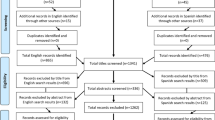

Procedure Our baseline study was conducted to explore the status quo of municipal service delivery to older persons, using a qualitative descriptive design proposed by Sandelowski (2000). The research started once ethical approval was granted by the Research Ethics Committee of the NWU. SALGA’s community development directorate emailed all 278 municipalities in the country requesting their participation. This communication was followed by an email to the person identified by each municipal manager’s office who would act as gatekeeper, clarifying the purpose of the research and method of participation through telephonic interviews or by email. It was emphasized that participation was voluntary, that withdrawal could take place at any stage without consequence, and that participants would not be paid. Confidentiality and anonymity would be assured by using numbers when we referred to participants’ verbatim quotations.

Most municipalities had difficulty in promptly indicating a specific, sufficiently knowledgeable person who could provide us with information about services for older persons. It took seven days on average for a municipality to identify such an older persons’ coordinator. In the course of our investigation, telephone calls were transferred from one person to another an average of 3.39 times, with a call lasting from three to 11 minutes. Our decision to obtain different perspectives on the basic services delivered by local government to older persons follows the principle that doing so would provide in-depth understanding of the topic under investigation (see Ellingson, 2009; Tracy, 2010).

Context and Participants We included the 278 municipalities (at the time of the study) in the nine provinces of South Africa to apply the necessary proportionate stratified sampling (see Table 2.2) that would ensure representativeness rather than generalization (Durrheim & Painter, 2006). For each province, the municipality of the capital city was included, and at least one metro, one district municipality, and one local municipality. To provide a representative sample of rural, urban, and semi-urban regions, 46 municipalities (17%) out of a total of 278 formed the final sample at the three levels of municipal government (local, district, and metro). Of the 38% of municipalities that participated in the research, 41% (n = 7) were situated in large cities, 18% (n = 3) in large towns, and 41% (n = 7) in small rural areas (Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs, 2016).

Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) with a vested interest in older persons’ affairs were also contacted for their perspectives on local government service delivery, and officials from SALGA and the Department of Social Development participated in focus groups.

Data Collection Information was obtained from 17 municipal officials and five participants affiliated with NGOs through telephonic semi-structured interviews or via email. Focus groups yielded different perspectives (Flick, 2014) and 26 officials from SALGA and the Department of Social Development participated in two focus groups. Verbatim transcriptions were made of the recorded telephonic semi-structured interviews and focus groups and complimented with the emailed responses.

Qualitative questions were compiled by researchers knowledgeable about issues affecting older persons and by experts in local governance, as presented in Box 2.1.

Box 2.1

Qualitative Research Questions to Obtain Information from Local Government Participants

-

1.

Are there any special services and programmes offered for older persons (the elderly/senior citizens) in your jurisdiction? If yes, tell me about them and what are they about. How are they executed? What are the scope and duration or sustainability of these? How many people are involved? Would you describe them as successful? (Each one listed) and if so why/why not? How is the impact evaluated? Why are you offering these programmes? What legislative framework drives you? Who provides funding, and how much is provided? (Each one listed.)

-

2.

Are there any other indirect benefits that older persons receive that are not part of the formal services or programmes you offer them?

-

3.

Do you have stakeholder partnerships with the private sector/NGOs/faith-based groups to deliver services/programmes?

-

4.

What are the needs for services and programmes for older persons in the communities you serve?

-

5.

How do/did you determine the needs for services and programmes for older persons?

-

6.

What feedback do you get from older persons about the services/programmes provided for them?

-

7.

What are the challenges that you experience with regard to the provision and implementation of services/programmes for older persons?

-

8.

What do you consider to be the role of local government (municipalities) with regard to the provision of services and programmes to older persons?

-

9.

How do you perceive the role of NGOs/faith-based organizations in the provision of services and programmes to older persons?

-

10.

What recommendations can you make to improve the current services and programmes that are delivered to older persons?

-

11.

What additional services and programmes for older persons would you propose?

Data Analysis All textual data were analysed thematically, using ATLAS.ti 8. The researchers familiarized themselves with the data by listening to the recorded interviews several times and reading the transcriptions. Data were coded and themes identified. Thematic maps were refined, named, and described. Researchers from different disciplines independently coded the data and discussed the themes until they reached consensus (see Clarke & Braun, 2013). Following Morse (2015) we conducted peer exploration of the themes among researchers, specialising in legislation and issues affecting older persons.

3.1.2 Findings

Three themes were identified from the information obtained: first, service delivery was compromised by an unclear mandate and silo-like functioning across different spheres of government as well as within local government; second, service delivery to older persons was not prioritized in the IDPs or in service delivery programmes; and third, while recognizing the valuable contribution of NGOs, lack of collaboration and support within the NGO sector and with local government hampered optimal utilization.

Unclear Mandate and Silo-Like Functioning Compromise Strategy and Service Delivery Local government officials saw the Bill of Rights (Constitution, 1996) the Older Persons Act of 2006 (Republic of South Africa, 2006), and the Older Persons’ Policy (Republic of South Africa, 2005) as too unspecific to determine their role and responsibilities towards older persons. The officials expressed uncertainty about their roles and responsibilities in delivering services to these residents, and they interpreted such tasks as belonging to the mandate of provincial government and its different departments. For example, the Department of Social Development (DSD) and the Department of Health overlap in the provision of certain services (e.g. home-based care programmes), with the result that the needs of many older beneficiaries were not addressed. A general lack of coordination with and support from district municipalities for local municipalities contributed to the confusion about who was responsible for what in a particular jurisdiction. Local municipalities pointed to inadequate internal, cross-sectoral coordination in terms of responsibility for specific services and programmes for older persons. Municipalities often did not know who their local older persons’ coordinator was, as Metro Municipality 12 explained:

Even within the structures of the municipality, the different groups of vulnerable people are treated or handled in silos—apart from each other. Therefore, what [our municipality] is trying to do is ‘transversal mainstreaming’ or ‘simultaneous mainstreaming’. I understand that certain groups have certain needs, but [am not sure how] to specify that they all have the following needs: housing, safety, participation in local government, access to jobs? And how do we make sure that this group of vulnerable people is not [made] more vulnerable by what we are doing or trying to do—or not doing.

The lack of a defined strategy for older persons is compensated for by offerings of ad hoc activities and once-off random events, such as a Christmas party hosted by the mayor, or other entertainments and outings, according to Local Municipality 5:

Those people in special groups [i.e. older persons], it is like they are an ad hoc. It is like sometimes they [the municipality] will remember to include us [local government special unit tasked with programmes for older persons], sometimes they won’t.

Older Persons Are Not a Priority in Terms of Programmes and Service Delivery Most of the municipalities referred to their IDPs as their framework for action. Older persons were mentioned (variously as older persons, elderly, pensioners, the aged) in most of the IDPs, but only a few municipalities included services or programmes for older residents specifically in their financial plans or development strategies.

Local authorities conceded that services and programmes for older persons were not a priority for the municipalities. These residents were often not indicated as a special group in the budgeting process, which according to Local Municipality 1, “focuses on other priorities such as HIV and AIDS, Early Childhood Development Programmes (ECDs), youth programmes and/or small farmers.” They explained that budgets are limited, particularly in rural areas, for delivering specific services and programmes to older persons; staff shortages and insufficient human resources mean too few officers are available to implement and sustain delivery of certain programmes; and the attitudes of municipal officers towards older persons and to units for special services representing older persons are often unresponsive. Metro Municipality 12 summarized the sentiments of other local government officials: “While issues like youth, gender, and disability are mandatory, the older person is not.” A somewhat contemptuous attitude was revealed when local government officials referred to older persons as a “very boring portion of society” (Local Municipality 6).

The Role of NGOs in the Provision of Service/Programmes Is Valued but Underutilized Most municipalities appeared to approve of the role that NGOs played within their municipal jurisdiction but generally failed to capitalize on this resource. Non-profit organisations, which fulfil many of the state’s obligations, expressed concern that service delivery was hampered by inefficiency and indifference from provincial governments, which are obliged to pay these organizations a welfare subsidy to render services. Lack of coordination and collaboration among different NGOs in specific communities led to duplication and further limited the effectiveness of service delivery.

3.2 Perspectives of Older Citizens

Older persons’ experiences regarding service delivery were obtained from three communities: Lokaleng (rural area), Ikageng (large town), and Sharpeville (large town) (Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs, 2016).

3.2.1 Method

Contexts and ParticipantsFootnote 1 The three communities, Lokaleng (n = 103), Ikageng (n = 94) and Sharpeville (n = 86) and its surrounding areas (n = 15)—which had links, respectively, to the three North-West University campuses (Mahikeng, Potchefstroom, and Vanderbijlpark)—were purposively selected, and criterion sampling as described by Patton (2002) was applied to select the participants. Lokaleng (Mahikeng) and Ikageng (JB Marks local municipality in Dr. Kenneth Kaunda district) are situated in the North West Province, and Sharpeville in (Emfuleni local municipality) in the Gauteng Province (see Chap. 3 for detail). A convergent or a concurrent design (see Fetters et al., 2013) was used. A sample of older persons completed questionnaires (n = 302Footnote 2) and participated in semi-structured interviews (n = 14) and focus groups (n = 22) about their needs and experiences relating to municipal service delivery.

Measure The Living Standard Measure (SU-LSM™) is a South African research measure consisting of 25 questions; it categorises the population in 10 levels, from 1 (lowest) to 10 (highest), to obtain a measure based on standard of living rather than the income of individuals (Eighty20, n.d.; Haupt, 2017; SAARF, 2017). The LSM measure groups people in the total population into relatively homogeneous groups according to criteria such as degree of urbanization, ownership of cars and appliances (Dodd, 2016; SAARF, 2014). The weighted values are translated by statistical calculations into 10 categories, ranging from low (1) to high (10). For the purpose of this chapter, these categories were reduced to five: low (1–2), below average (3–4), average (5–6), above average (7–8), and high (9–10).

Procedure A questionnaire (iGNiTe) was developed to obtain information from older participants about their cell phone use. It was piloted, checked, and used for data collection in 2013. In 2017, it was revised to obtain information not only about older persons’ cell phone use but also about their need for services in their local communities. Statistical analysis, review of recent literature, and transdisciplinary input informed the new version of the questionnaire (we-DELIVER), which was translated into various languages and used to gather data (see Chap. 4). The internal consistency (i.e. reliability) of the subsequent data obtained was evaluated and confirmation factor analysis was conducted in an attempt to confirm the proposed factor structure (see Chap. 5 for a detailed discussed). We included a list of services that older persons are inclined to use: emergency (ambulance and police); medical (hospital and clinic); welfare (social grants); housing; public transport; child care facilities; electrical services; and stormwater drainage. The reason for including child care facilities was the large number of older individuals (mainly older women) who take care of young children (Hoffman, 2019). We were aware that not all these services fell within the mandate of local government, but it was important for us to determine the extent to which older persons had access to the range of much-needed services. Qualitative questions were formulated to support the quantitative findings and used for the semi-structured interviews and focus groups.

To collect data from the older persons, we employed a strategy of facilitated engagement with technology, whereby trained student fieldworkers, familiar with the language and sociocultural context of the older participants, collected data on smart devices into Survey Analytics (see Chap. 3; see Chap. 6 for the findings).

On the data-collection days, the gatekeeper introduced the researchers to the older participants and explained the reason for the meeting (see Chap. 4). Older participants and student fieldworkers then paired off. Student fieldworkers introduced themselves to their participants and repeated the informed consent explanation to ensure inclusivity and knowledgeable consent. Older participants who were able to do so signed the informed consent form; others gave their consent orally (see Chap. 4).

Quantitative Data Analysis Data were analysed using statistical software packages SPSS 27 (IBM Corporation, 2021) and Mplus 8.6 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2021). Frequencies and valid percentages were first calculated and reported for LSM scores. LSM categories were then cross-tabulated with different areas, followed by non-parametric comparisons to identify possible significant differences per area. Lastly, LSM categories were cross-tabulated with the different services that older people are inclined to use. Missing data (a participant did not answer the question, data were captured inaccurately, or information was lost owing to system errors) were coded and excluded from the reported values.

Qualitative Data Analysis Data were transcribed verbatim, translated, back-translated by independent coders, anonymized and uploaded on ATLAS.ti 8. A thematic analysis framework was applied to find meaningful units of data, which were organized in themes (see Clarke & Braun, 2013). The relationships between the relevant themes and subthemes were explored and are presented in this chapter.

3.2.2 Findings

A breakdown of the different LSM groups is presented in Table 2.3, followed by the LSM scores of the three respective areas (Table 2.4).

The Kruskall-Wallis test found that LSM scores were significantly associated with the area in which older persons live [H(4) = 116.76, p < 0.001]. Step-down follow-up analysis showed that a large majority (77%) of older participants in Lokaleng reported lower levels of LSM (1–4) compared to participants in Ikageng and Sharpeville (5–8). Pairwise comparisons with adjusted p-values confirmed significant differences between LSM scores in Lokaleng, on the one hand, and Sharpeville (p < 0.001, r = −0.60) and Ikageng (p < 0.001, r = −0.71) on the other. No significant differences were found between LSM scores in Sharpeville and Ikageng (p = 1.00, r = 0.11). The effect size of the differences (interpreted according to Cohen, 1992) was shown to be large (r > 0.50), with the negative value indicating lower LSM scores in Ikageng.

The impact of a lower LSM score can be illustrated by the example of whether residents had tap water or flushing toilets inside their home. In Lokaleng (n = 103), only five older persons confirmed that they had running water (4.9%), compared with 62 in both Ikageng (n = 94; 66.0%) and Sharpeville (n = 86; 72.1%). In the total sample of households (n = 302), 66 participants (21.9%) drew hot water from a geyser.

Findings about the services that older participants accessed through cell phones (their own or by having one available when needed), are presented in Table 2.5, but most did not use their phones for this purpose.

Inadequate Services Older participants reported different levels of much-needed services available to them. In the rural setting, they complained about the lack of emergency services such as ambulances, as well as access to basic services such as water, safe housing, and public transport. An older Lokaleng resident was specific, saying: “We don’t have ambulances” and “I need running water, a geyser, a house and accessible public transport. Those are the things that would make life satisfactory.” Older recipients of services in the town of Ikageng expressed their need for services relating to good roads, safe public transport, a local community centre, local economic development (e.g. job creation), improved social security (e.g. food parcels), subsidized electricity, housing (e.g. rent), and public transport. For the most part, older residents complained about expensive services: “Rent and electricity—the rates are very high”, they explained; “Electricity rates are too high for us. They don’t last. We are forced to use other alternatives due to the fact that we can’t afford the units (subsidies needed)” and “My problems are also related to water and sanitation and a proper toilet.”

The service needs of older citizens in the town of Sharpeville were expressed in relation to economic development (jobs must be created, or a suitable community centre provided, which would enable them to meet in bad weather): “I mean what would it be like if we could receive a place and they build a centre for us? You can hear this iron roof is making such a noise.” (It was raining on the day of data collection).

Services were not always delivered age-appropriately. For example, older persons were expected to walk long distances on uneven terrain to reach public transport or to access medical services: “Our clinic is quite a distance”; and “If they could just bring it closer to us”. Water was available, but only from a communal tap: “[We] need water in our yards. The community taps are too far.”

Unresponsive Behaviour by Local Government Officials Older citizens experienced local government officials as unresponsive when they reported absent or inadequate service delivery. An older person in Lokaleng explained: “We go to the municipality and complain, but they don’t help with anything.” In Ikageng, older persons reported that “there is a ward committee that is closer to the people [who] take the complaints of the people. And at every monthly meeting that the councillor holds, the complaints are there for the councillor to attend to.” But seemingly these complaints are met without resolution: “I complain to the councillor, every time we have a meeting with him.” In some instances, older persons never saw their councillors. In Sharpeville, the older recipients of services confirmed their inability to reach the authorities and experienced “no help from municipality when phoning them”. The older persons in both rural and urban areas complained that trying to extract a response from local government was expensive and often futile, and offered examples: “Most of the time, they do not answer when we call, or they are too busy to help. Sometimes they say they will come, but they never do”; and “Besides, when we look for a councillor it is impossible to find one. Even if you try calling him it is difficult to find him”; and “I once put on my shoes and I went to his house. I explained to him that the older people need you there. In this new year, you need to pull up your socks and be present next to them. And then he said he is busy and will see when he gets time.”

Individual and Social Support Supplements Poor Local Government Service Delivery

When older persons failed to obtain information or have their pressing needs for basic and municipal service delivery addressed, they resorted to visiting the local government offices. An older woman said that the only way to get their service needs addressed was to “go there [municipal offices] personally”. However, for some people this was not a viable option because they suffered ill-health or lacked social support: “I ask for help because I don’t have, I live on my own. That’s why I ask for help from my neighbours.” Consequently, older persons had to draw on support from their social networks. In rural Lokaleng, the older persons drew on an extended communal support system, under a tribal authority: “When I need information, I ask the chief or the ward councillor.” They also asked their children, grandchildren, peers, and extended family, as well as people nearby, their friends, and other older persons.

4 Critical Reflections towards ICT Interventions

South African law is aligned with African regional and international guiding frameworks to promote age-inclusive communities. On the face of it, South Africa has a robust law and policy framework, applicable to municipal service delivery to all citizens, including older persons. Local government, as the state organ closest to the citizens, is best suited (and, as such, is expected) to provide contextually relevant services that involve people meaningfully in public decision-making. It is, furthermore, required to apply resources appropriately to support residents in vulnerable situations in their jurisdiction by fulfilling the presumed agreement between state and society (Kaplan, 2017). Case law also highlights the importance of local service delivery, in that courts have not hesitated to point to the service delivery duties of municipalities as, for example, in the Constitutional Court case of Joseph v City of Johannesburg and Others (2010 (3) BCLR 212 (CC)). In this judgment, the country’s highest court found that:

The provision of basic municipal services is a cardinal function, if not the most important function, of every municipal government. The central mandate of local government is to develop a service delivery capacity in order to meet the basic needs of all inhabitants of South Africa … (see par. 34).

The social contract is generally normatively—de jure—acknowledged in state–society relations in South Africa. When applied as an analytical and policy (non-normative) tool to concrete processes and settings where older persons are concerned, contracts are often de facto broken or even revoked and should be (re)negotiated. The resultant disequilibria between state and society and intra-societal relations have a detrimental effect on individuals’ sense of personal coherence (Fournier et al., 2018) and on the broader sense of social cohesion (UNDP and NOREF, 2016).

Our research reveals that older persons with a low LSM score who live in rural communities have an urgent need for basic services. They generally reported limited access to water and electricity, poorly developed infrastructure, and age-inappropriate services. In more resourced communities such as Ikageng and Sharpeville with higher LSM scores, there were higher-level service needs. In these settings, older persons expressed needs related to the promotion of life satisfaction, which would contribute to their dignity, such as: economic development opportunities, good roads, age-appropriate communal meeting venues, and a responsive local government. Our data-collection experiences as we attempted to locate relevant local government officials for information about services and programmes to older persons showed that it was costly to try (often in vain) to elicit appropriate responses from local government officials generally, let alone to find an official with information specific to the issue at hand. Depending on their individual circumstances, the older citizens in our study resorted to two strategies to address their service needs. First, they drew on support from social networks close by and, second, they paid their local government offices a personal visit. Not all of them, however, had a sufficient support network, financial means or agency to apply such strategies and the literature shows that, for some, the outcomes can be dire (Hoffman & Roos, 2021). NGOs play an important role in supplementing local governments’ inappropriate or failed response to older persons. Unfortunately, optimizing the benefits from NGOs is compromised by lack of communication and coordination between them and in relation to local government.

Based on the service delivery issues and the general tension in the state–society equilibria, we identified obvious systemic gaps. To partly address the dilemmas associated with effective service delivery, we offer broad suggestions also relating to the role that technology as mediating modus could potentially play to (re)negotiate the relationship between (older) citizens and the state to address their needs as part of the state–society social contract.

Systemic Gaps in Service Delivery

The real and perceived frustrations that older persons experience in relation to local government service delivery lie at the level of law and policy implementation. Considering that the government comprises three spheres that are interrelated and co-responsible for implementing people’s rights (see 7(2) of the 1996 Constitution), it may be expected of national and provincial authorities (as well as the courts) to step in and create a safety net when municipal systems fail. This disconnect between the government sphere and service recipients has implications for everyone, but more profoundly for older persons as a marginalized group. A further consideration is the notion of contextual relevancy: people in different contexts have different service delivery needs and require different and appropriate modes of delivery, fit for their context. Even though government (any sphere) provides some services, recipients find that they must—more often than not—employ their own complementary solutions to access the services they need. The difficulties for those challenged with limited resources, support structures or mobility are obvious.

Interventions towards Service Delivery

To address the systemic lag in service delivery, we list three possible interventions. We focus on the use of technology, reflecting the aim of this volume.

-

1.

On a policy and organizational level, local municipalities can (re)establish a dedicated unit focusing on age-inclusive communities in line with the World Health Organization’s Age-Friendly Programme (WHO, 2007). Such a unit can assess older persons’ context-specific needs and identify appropriate modes of delivery to design and implement tailor-made, sustainable programmes, affordable services, and interventions to equip older persons with the knowledge and skills needed to promote ageing well. Infrastructure can be refurbished to accommodate the functional needs of older persons, such as dedicated service counters and allocated parking spaces, and accessible and safe public transport can be made available.

-

2.

On an advocacy level, the participation of older individuals could be enabled through associations and organizations, or mechanisms for their institutional representation. Establishing a platform ‘to speak with one voice’ can help both to define the specific needs of this group and to limit duplication of services and develop the optimal use of limited resources. Discussion forums at community, ward or municipal level that are accessible to older persons or their representatives are effective ways for them to raise issues affecting their lives and thereby to improve accountable service delivery. Municipal service partnerships involving community-based organizations and community development workers can also make services more accessible to older individuals.

-

3.

To address gaps in (effective) service delivery in ways that meet the needs of marginalized groups (and beyond), and to explore the as yet untapped potential offered by ICT, it is imperative to draw on the agency of affected groups. We suggest that ICT offers the potential to do just that for older persons who seek effective municipal service delivery: it provides access to information as well as swift communication and feedback opportunities to keep local government accountable.

5 Conclusion

This chapter highlights the disconnect between the vision and stipulations of international, African regional and South African law and policy for municipal service delivery and the daily service delivery experience of local government officials and by older recipients (as a marginalized group in society). Our findings underscore the depth of the implementation deficit in South Africa; its impact is tangible and gives cause for concern—it frustrates efforts to improve the well-being and socio-economic development of older persons, and it thwarts the ideal of inclusivity in municipalities.

Systemic problems in local government cannot realistically be fixed overnight. Those responsible for steering municipal service delivery could, however, find it helpful to draw on a promising and progressive law and policy base as well as on the growth and uptake of technology by older people. We therefore advance the argument to consider alternative means to improve access to information about and participation in municipal service delivery by older persons as active agents. One solution would be to use ICT to promote effective communication and processes that make it possible for older persons to access information about services and provide new opportunities for them to give input and feedback.

Notes

- 1.

Four participants did not indicate where they live.

- 2.

The reported frequency numbers may differ from the total number of participants due to missing data on certain items, thus not necessarily adding up to the total sample size of 302.

References

African Commission on Human and People’s Rights (ACHRP). (1981). African charter on human and People’s rights. https://www.achpr.org/legalinstruments/detail?id=49

African Union/HelpAge International (AU/HAI). (2003). African union policy framework and plan of action on ageing. Nairobi. https://www.helpage.org/silo/files/au-policy-framework-and-plan-of-action-on-ageing-.pdf

African Union/HelpAge International. (2003). Protocol to the African charter on human and peoples’ rights on the rights of women in Africa. https://au.int/en/treaties/protocol-african-charter-human-and-peoples-rights-rights-women-africa

African Union (AU). (2011). African charter on values and principles of public service and administration. Assembly of the African Union. https://au.int/en/treaties/african-charter-values-and-principles-public-service-and-administration

African Union (AU). (2015). Agenda 2063: The Africa we want.. https://au.int/en/agenda2063/overview

African Union (AU). (2016). Protocol to the African charter on human and peoples’ rights on the rights of older persons in Africa. Addis Ababa. https://au.int/sites/default/files/pages/32900-file-protocol_on_the_rights_of_older_persons_e.pdf

Atkinson, D. (2007). Taking to the streets: Has developmental local government failed in South Africa? In S. Buhlungu, D. Daniel, R. Sotuhall, & J. Lutchman (Eds.), State of the nation: South Africa 2007 (pp. 53–77). Human Sciences Research Council.

Avgerou, C. (2010). Discourses on ICT and development. Information Technologies and International Development, 6(3), 1–18.

Banjo, A., & Jili, N. N. (2013). Youth and service delivery violence in Mpumalanga, South Africa. Journal of Public Administration, 48(2), 251–266. https://journals.co.za/content/jpad/48/2/EJC140017

Booysen, S. (2012). Sideshow or heart of the matter? In Local politics and South Africa’s 2011 local government elections. Local elections in South Africa: Parties, people and politics (pp. 1–10). SUN Press.

Johnston, S., & Bernstein, A. (2007). Voices of anger. Protest and conflict in two municipalities. The Centre for Development and Enterprise. https://www.cde.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Voices-of-Anger-full-report-1.pdf

Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2013). Teaching thematic analysis: Over-coming challenges and developing strategies for effective learning. The Psychologist, 26(2), 120–123.

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159.

Constitution. (1996). Accessed Feb 12, 2014, from http://www.gov.za/documents/constitution/1996/a108-96.pdf

Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs. (2016). Integrated urban development framework.. https://iudf.co.za/knowledge-hub/documents/

Dodd, N. M. (2016). Household hunger, standard of living and satisfaction with life in Alice, South Africa. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 26(3), 284–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2016.1185918

Durrheim, K., & Painter, D. (2006). Collecting quantitative data: Sampling and measuring. In M. Terre Blanche, K. Durrheim, & D. Painter (Eds.), Research in practice: Applied methods for the social sciences (pp. 131–159). UCT Press.

Eighty20. (n.d.). LSM calculator. https://www.eighty20.co.za/lsm-calculator/

Ellingson, L. L. (2009). Engaging crystallization in qualitative research: An introduction. Sage.

Fetters, M. D., Curry, L. A., & Creswell, J. W. (2013). Achieving integration in mixed method designs–principles and practices. Health Services Research, 48(6 Pt 2), 2134–2156. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12117

Flick, U. (2014). An introduction to qualitative research (5th ed.). Sage.

Fournier, M. A., Dong, M., Quitasol, M. N., Weststrate, N. M., & Di Domenico, S. I. (2018). The signs and significance of personality coherence in personal stories and strivings. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 44(8), 1228–1241. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167218764659

Haupt, P. (2017). The SAARF universal living standard measure (SU-LSM™): 12 years of continuous development. South African Advertising Research Foundation.. http://www.saarf.co.za/lsm/lsm-article.asp

Heeks, R. (2010). Policy arena: Do information and communication technologies (ICTs) contribute to development? Journal of International of Development, 5(640), 625–640.

Hoffman, J. (2019). Second-parenthood realities, third-age ideals: (grand)parenthood in the context of poverty and HIV/AIDS. In V. Timonen (Ed.), Grandparenting practices around the world: Reshaping family (pp. 89–110). Bristol University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv7h0tzm.10

Hoffman, J., & Roos, V. (2021). Postcolonial perspectives on rural ageing in (south) Africa: Gendered vulnerabilities and intergenerational ambiguities of older African women. In M. Skinner, R. Winterton, & K. Walsh (Eds.), Rural gerontology: Towards critical perspectives on rural ageing (pp. 223–236). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003019435

IBM Corporation. (2021). IBM SPSS statistics for windows, version 26.0. IBM Corporation.

Joseph v City of Johannesburg and Others 2010 (3) BCLR 212 (CC).

Kanungo S. and Kanungo P. (2004). Understanding the linkage of ICT to other developmental constructs in underserved and poor rural regions. In PACIS 2004 Proceedings. Paper 18, 222–235.

Kaplan, S. (2017). Inclusive social contracts in fragile states in transition: Strengthening the building blocks of success. Institute for Integrated Transitions.

Koma, S. B., & Modumo, O. S. (2016). Whither public administration in South Africa? The quest for repositioning in the 21st century. Africa's Public Service Delivery & Performance Review, 4(3), 482–487.

Kroukamp, H., & Cloete, F. (2018). Improving professionalism in south African local government. Acta Academica, 50(1), 61–80. https://doi.org/10.18820/24150479/aa50i1.4

Mann, C. L. (2003). Information technologies and international development: Conceptual clarity in the search for commonality and diversity. Information Technologies and International Development, 2(1), 67–79.

Morse, J. (2015). Critical analysis of strategies for determining rigor in qualitative inquiry. Qualitative Health Research, 25(9), 1212–1222. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315588501

May, A. (2010). The withholding of rates in five local municipalities. Recognising Community voice and dissatisfaction, 5, 96–110. https://ggln.org.za/media/k2/attachments/SoLG.2011-Community-Law-Centre.pdf

Muggah, R., Sisk, T., Piza-Lopez, E., Salmon, J., & Keuleers, P. (2012). Governance for peace: Securing the social contract. United Nations Development Programme.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2021). Mplus: Statistical analysis with latent variables: User’s guide (8th ed.). Muthén & Muthén.

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Sage.

Pozzebon, M., & Diniz, E. (2012). Theorizing ICT and society in the Brazilian context: A multilevel, pluralistic and remixable framework. BAR. Brazilian Administration Review, 9(3), 287–307. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1807-76922012000300004

Reddy, P. S. (2016). The politics of service delivery in South Africa: The local government sphere in context. The journal for transdisciplinary research in southern. Africa, 12(1), 1–8. a337. https://doi.org/10.4102/td.v12i1.337

Republic of South Africa. (1998a). Local government: Municipal systems act. 32 of 2000.

Republic of South Africa. (1998b). Local government: Municipal structures act 117. of 1998.

Republic of South Africa. (1998c). White Paper on Local Government (1998).

Republic of South Africa. (2000). Promotion of Access to Information Act 2 of 2000.

Republic of South Africa. (2005). Intergovernmental relations framework act. 13 of 2005.

Republic of South Africa. (2006). Older persons act. 13 of 2006.

Sandelowski, M. (2000). Whatever happened to qualitative description? Focus on Research Methods, 23, 334–340. http://www.wou.edu/~mcgladm/Quantitative%20Methods/optional%20stuff/qualitative%20description.pdf

South African Audience Research Foundation (SAARF). (2014). Demographics of the 10 SAARF LSMs. http://saarf.co.za/lsm-demographics/LSM%20Demographics%20Jul%2012-Jun%2013.pdf

South African Audience Research Foundation (SAARF). (2017). Living Standards Measurement. http://www.saarf.co.za/lsm/lsms.asp

South African Government. (2012). National Development Plan 2030. https://www.gov.za/issues/national-development-plan-2030

South African Local Government Association (SALGA). (2015). 15 years review of local government: Celebrating achievements whilst acknowledging the challenges. https://www.salga.org.za/Documents/Knowledge%20Hub/Local%20Government%20Briefs/15-YEARS-OF-DEVELOPMENTAL-AND-DEMOCRATIC-LOCAL-GOVERNMENT.pdf

Stats SA (Statistics South Africa). (2016). The state of basic service delivery in South Africa: In-depth analysis of the community survey 2016 data/statistics South Africa (p. 120). Statistics South Africa. Report No. 03-01-22 2016.

Stoffels, M., & Du Plessis, A. A. (2019). Piloting a legal perspective on community protests and the pursuit of safe(r) cities in South Africa. Southern African Public Law, 34(2), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.25159/2522-6800/6188

Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight "big-tent" criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(10), 83–851.

United Nations (UN). (1982). Report of the world assembly on ageing. . https://www.un.org/development/desa/ageing/resources/vienna-international-plan-of-action.html#:~:text=It%20was%20endorsed%20by%20the,of%20its%20city%20of%20origin

United Nations (UN). (2002). Madrid international plan of action on ageing. United Nations. http://undesadspd.org/Portals/0/ageing/documents/Fulltext-E.pdf

UNDP (United Nations Development Programme) and NOREF (Norwegian Peacebuilding Resource Center). (2016). Engaged societies, responsive states:The social contract in situations of conflict and fragility. New York: United Nations Development Programme.

United Nations General Assembly. (1948). Universal declaration of human rights. https://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/

United Nations General Assembly. (1966a). International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. https://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CCPR.aspx

United Nations General Assembly. (1966b). International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. https://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CESCR.aspx

United Nations General Assembly. (1991). Principles for Older persons. https://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/OlderPersons.aspx#:~:text=Older%20persons%20should%20be%20able%20to%20live%20in%20dignity%20and,independently%20of%20their%20economic%20contribution

United Nations General Assembly. (2016). The new urban agenda. https://habitat3.org/the-new-urban-agenda/

Walsham, G., Robey, D., & Sahay, S. (2007). Foreword: Special issue on information systems in developing countries. MIS Quarterly, 31(2), 317–326. https://www.uio.no/studier/emner/matnat/ifi/INF9200/v10/readings/papers/WalshamRobeySahay.pdf

World Bank. (2011). Accountability in public service in South Africa. World Bank.

World Health Organization (WHO) (2007). Global age-friendly cities: A Guide https://www.who.int/ageing/publications/Global_age_friendly_cities_Guide_English.pdf

Acknowledgements

Ms. A Stols for obtaining data from local government officials; Mss M Mallane and W Manganye of the South African Local Government Association, who supported and funded the baseline research on service delivery to older persons at municipal level in South Africa; and Professor M Ferreira for critical insights.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Roos, V., du Plessis, A., Hoffman, J. (2022). Municipal Service Delivery to Older Persons: Contextualizing Opportunities for ICT Interventions. In: Roos, V., Hoffman, J. (eds) Age-Inclusive ICT Innovation for Service Delivery in South Africa. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-94606-7_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-94606-7_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-94605-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-94606-7

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)