Abstract

Ageing population is one of the most fundamental socio-economic transformations of the twenty-first century, with significant policy implications. China, the world’s most populous nation, is no exception. The necessity for cost-effective, culture-appropriate and sustainable eldercare services is one of the Government’s priorities, in both present and future. This research uses a focus-group interviews methodology to explore sustainable models of eldercare services through an in-depth comparative analysis of care demands and service provision in two Chinese cities. The study reflects a prevailing trend of the integrated-care service mix in line with the United Nations’ five most relevant Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs 1, 3, 5, 10, 11) for older adults. In addition to the 7Ps of the service marketing mix, this article highlights the particular importance of ‘Partnership’ in sustainable care delivery in China. The past-present-future scenario and the thematic analysis of older adults’ pattern-matching add two unique dimensions to population ageing and eldercare studies: ‘People’ and ‘Partnership’.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The age structure of the world population is driven by increasing levels of life expectancy and decreasing levels of fertility. Globally, the number of older adults aged 65 years or over (65 +) is projected to double from 727 million in 2020 to over 1.5 billion in 2050, and the related ratio is expected to increase from 9.3% to 16.0% (United Nations [UN], 2020). Furthermore, the population aged 60 and above (60 +) is estimated to reach nearly 2 billion by 2050 (UN, 2020). With such rapid growth of population ageing worldwide, all governments are struggling to cope with the consequences.

Unsurprisingly, the ageing population rate in China even surpasses that of many developed countries (Zheng et al., 2020). The 7th National Census (National Bureau of Statistics [NBS], 2021) reports that nationwide the number of older adults, aged 60 + and 65 + , has reached 264 million and 190.63 million, accounting for 18.7% and 13.5% of the total population, respectively. Historically, NBS (2020) records a substantial rise in the number of 65 + older adults in China, from 88 million in 2000 to 176 million in 2019. According to the Institute of Gerontology, Renmin University of China (2016), the size of the 60 + older population will double in thirty years, from 250 million in 2020 to 450–500 million by 2050. Incontestably, China has faced several challenges as a rapidly ageing society and will have to tackle the sustainability issue of eldercare services in the long run.

Understanding the interrelatedness between the older adults’ care demands and their lifecycle, together with their cultural imprint, is of great relevance to sustainable care services. The sustainable development goals (SDGs) pledged by the United Nations (UN, 2015) call for an end both to poverty in all its forms everywhere (SDG1) and to discrimination against women, to achieve gender equality and empowerment of all females (SDG5), ensuring that by 2030 all people at all ages enjoy peace and prosperity in healthy lives and well-being (SDG3), reducing inequalities by bridging the widening disparities (SDG10), and creating inclusive, resilient human settlements and safe, sustainable city communities (SDG11) due to the dramatic growth of urban population and migration.

The UN has declared 2021–30 the ‘Healthy Ageing Decade’: the sustainability of eldercare services is a crucial but complex topic, especially due to the necessity to guarantee both safety and quality. Across many countries, and China is no exception, ‘healthy ageing’ has become a major collaborative area for research and practice. Therefore, the final aim of this study is to explore both theoretical and practical trends of sustainable eldercare solutions, with particular attention to the five SDGs, to evaluate how to improve the conditions of older adults in China’s present and future. This study focuses on one crucial question while tackling a complex set of issues faced by most of the Chinese older population: How could care services be integrated and offer a more inclusive approach to meet the needs of equality, prosperity, and sustainability of the ageing society through adequate institutional arrangements?

To address this question, the authors investigated two representative Chinese cities: Ningbo (an eastern coastal vice-provincial city in Zhejiang province) and Yichang (at the heart of China along the Yangtze River of Hubei province). The two cities share a humid subtropical monsoon climate with four distinctive seasons but have different dialects, dietary habits, and development paces. Both cities registered increasingly ageing populations in the past decade, but Yichang was characterized by ethnic minority inhabitants while Ningbo was noticeable for its migrant residents. From 2010 to 2020, Yichang’s population remained stable at 4 million, while Ningbo’s resident population reached 9.4 million, growing over 20% because of the increasing inbound migration (see Table 1). This explains why the 60 + ageing population in Ningbo (1.7 million) was much larger than that in Yichang (1.0 million), but in reverse, the 60 + ageing ratio in Yichang (25%) appeared higher than that of Ningbo (18%). In addition, there was a significant gap in average per capita disposable income and living expenses across these two cities.

In association with the five SDGs in the two comparative city scenarios, this study attempts to conceptualise a framework for sustainable eldercare. Building upon the existing literature, the study first compares the expectations and perceptions of care services through relevant focus group interviews, then correlates both theoretical and practical trends of sustainable eldercare options, and finally concludes by evaluating the applicability of the 7P—‘product, price, place, promotion, people, process, physical evidence’ (Booms and Bitner, 1981, as cited in Rafiq & Ahmed, 1995) and adding the eighth P for ‘partnership’ (Zheng et al., 2020), thus offering a major contribution to the sustainability model of eldercare services in China.

Conceptualization of Sustainable Eldercare Services

The concept of eldercare service is embedded in the household-institution-society system. ‘Care’ and ‘service’ are distinguished by the older adults’ needs, and ‘care’ is usually determined by the recipients’ ability to fulfil the tasks or activities themselves (Szebehely, 1996). The conceptualisation of sustainable eldercare services is based on service integration, social inclusiveness, and institutional arrangements.

An Integration-based Approach

Eldercare services take place formally or informally, influenced by direct variables (e.g., accommodation, health, residence, education, and special needs) and combined variables (e.g., chronic diseases, life satisfaction, living standard, marital status, disability, depression, and cognition) (Rajan et al., 2020). The scholarly literature reveals that there are significant differences between formal and informal care, laying a firm foundation for the integration of eldercare services.

The older adults who require ‘care’ or are forced to accept ‘care’ are mostly affected by serious health conditions and/or require specific living arrangements (UN, 2020). Those living alone, suffering from severe chronic or diagnosed diseases, mental illness, and functional disabilities, and being confined to bed and at home, are more likely to receive formal care (Rajan et al., 2020), especially healthcare such as medical, nursing, and mental care as listed in Table 2 (Özsungur, 2020). Therefore, eldercare services combine health- and life-care, and the provision of health-life care depends on one’s health conditions.

The increasing burden of ageing population is also claimed to drive innovation and application of technology (e.g., Pekkarinen et al., 2020) in the care sector. For instance, data management tools and sensor app infrastructure could assist care managers in measuring residents’ and nurses’ behaviours and increase their awareness of the potential quality match between residents’ needs and care provisions (Klakegg et al., 2020). Smart care can be provided with health, nursing, safety, and auxiliary support for independent, assisted, or dependent older residents. E-health practice with humanoid robots (Gonzalez-Jimenez, 2018) and social robots (Kalisz et al., 2021) proves to be applicable in eldercare (e.g., dementia care, emotional care, stroke rehabilitation).

Zhang et al. (2020) argue for a rising smart care demand in China because of changing family structure, migration flows, increasing numbers of chronic diseases, and the weakening of filial care. Smart care services can offer valuable contributions to enhancing both care insights and the overall quality of eldercare services. Complementing traditional eldercare, smart care assists healthy ageing, through the integration of health and life care, as well as the offer of emergency and emotional aid (Zhou, 2019). However, the challenges associated with technology implementation from a multi-actor perspective, mainly users’ readiness for adoption, should be fully understood (Svensson et al., 2021). This implies that understanding people’s experiences (especially caregivers and receivers) and their perception of digital-assisted technology are the necessary prerequisites for the successful introduction of smart care.

Social care for older adults has increasingly used mixed models. From a psychological perspective, the principle of the importance of older adults being nursed in their living places is predominant in European countries (UN, 2020). Buurtzorg, translatable as ‘neighbourhood care’, was first created in the Netherlands, offering a good example (Johansen & Bosch, 2017) of integrating formal care into informal contexts. The National 9073 Eldercare Guidelines (China Development Research Foundation [CDRF], 2020) refer to the older Chinese population’s 90% home care, 7% community care, and 3% residential care.

Indeed, the eldercare services’ provision is country-, culture-, and context-specific. The different types of care provisions and platforms reflect and reshape the desires and wishes of older adults and their families. Although families are expected to play the most active role in informal care, choosing whom to include in the social consideration for eldercare and how to integrate additional features and added-value functions into viable care models with sufficient care professionals are equally crucial to the future sustainability of eldercare services.

An Inclusion-driven Approach

In a familialist regime, how families cope with care needs and how policies support them become vital for the sustainable development of eldercare services (Hrast et al., 2020). Since daily activities of living (DAL), instrumental daily activities of living (IDAL), and cognitive impairment (Connolly et al., 2017) are much more severe in older adults aged 80 + , these are more in need of assisted or dependent living and deserve higher priority in social inclusion for eldercare services, especially if they have limited family/financial support.

Meanwhile, women represent the majority of older adults requiring more IDAL assistance, cognitive help, and long-term care (UN, 2020). While women are the major caregivers, they also have higher chances of being single or divorced, and poorly educated (UN, 2020). Therefore, the inclusiveness of females, as both potential care professionals and receivers, requires special attention in the development of eldercare services.

In ageing Europe, multicultural migrants have been strongly correlated to the change in older adults’ demands and care labour (Gavanas, 2013). For instance, older migrants have significantly increased in Sweden and Switzerland: with the privatisation of eldercare in these developed countries and the marketisation of newly emerged ageing society, female eldercare migrants are evidence of today’s new gender roles (Gavanas, 2013; Schwiter et al., 2018). Considering the local-versus-migrant older people phenomena, the mobility pattern shows that women from poorer places move to care for older adults in richer areas. A similar trend of older adults’ migration and caregivers’ movement has also been identified in China (Ying et al., 2019).

Whilst a transformation of gender and migration regime changes pre-assumptions about care responsibilities, staffing of care professionals is viewed as a critical challenge for the sustainability of eldercare services in the future. In particular, female workers are extremely sensitive to what are seen as more warm-hearted feelings such as dignity, respect, trust, recognition, appreciation, and social status (Gavanas, 2013; Ronnqvist et al., 2015; Martín Palomo et al., 2020). Migrant women’s motivation to act as care workers is connected to the idea of giving them hope for their retired lives and cross-cultural working skills that can help to overcome barriers to social inclusion.

A resilient human settlement needs well-trained staff, well-equipped facilities, and well-supported finance (Isa et al., 2020). Basic shelter, healthy food, comfortable living, enhancement activities, quality service, and public involvement are required (Wagiman et al., 2016) for all entitled older adults. To attain all this, an inclusion-driven approach to eldercare services requires a cost–benefit analysis that informs the institutional arrangements of eldercare services.

An Institution-oriented Approach

Grudinschi et al. (2013) suggest that, in an evolving socio-economic society, the public–private relationship plays a central role in acquiring sustainable care services. Whilst the privatisation of eldercare in Sweden is a good example of quality enhancement and cost reduction (Bergman et al., 2016), publicly funded care services are often provided via retirement homes or home care. On the contrary, the mixture of care solutions by semi-private care providers between public and private funders is usually recommended (Lapidus, 2019).

Originated from the UK, Zheng et al. (2020) refer to the public–private partnership (PPP) as the cooperative relationship between government and private sector (either for-profit enterprises or not-for-profit organisations) due to the trend of public activities and the need for private financing, risk-sharing, and better results for public goods or services. Due to imbalances in the existing supply–demand of formal institutional care, the PPP model is praised by Zheng and others (2020) as a good opportunity for eldercare services development in China.

Integrating the unique resources and capabilities of various partners, PPP could facilitate service innovation and care efficiency of the supply chain (Grudinschi et al., 2013). For instance, care providers can gain medical support by creating a strategic partnership with medical institutions or outsourcing cleaning and security services. In principle, the public sector could organise care services for older adults and perform management initiatives whilst the private partner should highlight the importance of social responsibility (Zheng et al., 2020). However, the implementation of PPP in many healthcare establishments has been requested to further improve effectiveness and efficiency (Ray, 2019). Although the payment can be flexible (either by the users or through government subsidies), the use of PPP in China’s eldercare sector still calls for attention to the supply–demand ratio and the investment’s requirements.

Montfort et al. (2018) suggest that the public–private mix in China could learn useful lessons from the institutional evolution of the social welfare provision systems in the Netherlands. According to their opinion, it is necessary to activate and evaluate both government and private sectors. While resource allocation and quality improvement can be optimised and enabled, the integration of care services will eventually respond to the dynamic demands of older adults and the existing/emerging supply by public and private care providers. The public–private mix for eldercare in China would arguably be unique, having Chinese characteristics.

‘Partnership’ has been advocated for the potential improvement of health and eldercare provisions (Ray, 2019; Zheng et al., 2020). Based on the 7P service mix, healthcare shows a well-established mix [product (services), price, place (location), promotion, people, process, and physical evidence] (Chana et al., 2021). However, considering the necessity for integrated, inclusive, and institutional approaches to eldercare studies, we argue that a combination of 3I and 8P could be used as a conceptual framework to explore the eldercare service mix (Fig. 1).

Methodology

To explore sustainable eldercare solutions, it is essential to analyse the existing care supply–demand scenario and the critical challenges that older adults and their families face. Since China is a large country with considerable internal differences, a comparative study across two different cities has been conducted. To delineate a past-present and future scenario (Gjellebak et al., 2020), it was essential to understand individual past experiences, present perceptions, and future expectations regarding eldercare through focus-group interviews.

Comparative Scenarios

This study adopted a comparative approach taking into consideration that the needs of older adults and their families vary from generation to generation and from place to place. The two cities, Yichang and Ningbo, were chosen because they are complementary to each other in terms of city profiles, citizen patterns, and ageing parameters. The research consisted of an ongoing longitudinal study in both cities between 2016 and 2021.

According to both municipal civil affairs bureaus (2021), their eldercare service targets were ‘9064’ and ‘9055’: this meant 90% of older populations in Yichang and Ningbo in-home care, with Yichang aiming at covering 6% with community-based care and 4% with residential care while Ningbo 5% community-based care and 5% residential care. The supply capacity of eldercare beds in Ningbo (70,000) was twice higher than Yichang’s (35,000); the average number-of-beds per hundred-older-adults in Yichang and Ningbo resulted in 3.3:4.4, respectively. Both governments emphasized a relatively balanced public–private ratio for residential care facilities, a well-developed home- and community-based care infrastructure with tech support, and aimed for better integration of medical-care and eldercare.

While Yichang is one of the third-tier cities, Ningbo ranks among the newly rising first-tier cities.Footnote 1 The two cities have similar pension schemes, but the difference in economic development leads to very different income levels, service expectations, and willingness to accept/pay for care services from one place to the other. These cities provide good contrast in exploring Chinese characteristics of eldercare services.

Focus-Group Interview

This research adopted focus-group interviews because this technique has proved to be effective with older adults (Heller et al., 1990) and popular within the healthcare sector (Rabiee, 2004), in addition to its wider use in marketing research (Hyman & Sierra, 2016) and inter-disciplinary studies (e.g., Gjellebak et al., 2020). It is believed to be an appropriate method for our study to gather relevant information about our target audiences’ ideas and feelings (e.g., Rabiee, 2004) of eldercare as well as their perceptions and perspectives (e.g., Heller et al., 1990) on care services.

This approach helps to explore end-users care needs and concerns not yet addressed by existing providers. It is an important instrument to gain the opinions and expectations of prospective users on the 7Ps such as facility design (physical evidence), care package (product), and pricing scheme (price). Although focus-group interviews are expensive (Hyman & Sierra, 2016) in comparison with questionnaire surveys, the dynamics of sharing personal attitudes and feedback in a group (8–12 persons on average) and their flexibility offers valuable insights that questionnaire surveys and individual interviews are unable to achieve (Heller et al., 1990).

By official definition,Footnote 2 the main participants are 60 + older adults. However, with the rise of open-minded middle-class citizens and the current regulations on retirement age in China, the features and needs of the nearly-retired (aged 50–60)Footnote 3 and their willingness to accept/pay are also critical for sustainable care development. Individuals aged 50 + but below 60, representing older adults in thirty years, are therefore included in focus-group interviews.

During the decision-making process, older adults and their spouses and children form a chain of decision-makers, participants, and influencers. For financial affordability and sustainability, older adults and their families create a strong economic alliance referring to what they expect to receive from eldercare services. Whether one has spouse companionship and care support from their children affects their eldercare choice. Hence, focus-group interviewees also extended to family members.

While older adults and their families’ life philosophy and needs should be taken into consideration, other relevant stakeholders’ opinions are also important for the future sustainable supply of eldercare services. For this reason, this research encompassed civil affairs bureau officials, sub-district office and community commission workers, and healthcare and eldercare professionals in focus-group interviews. These individuals also offered invaluable support, in both cities, approaching older adults and their family representatives, organising focus-group meetings, providing appropriate venues, building relationships with participants and even helping with local dialects.

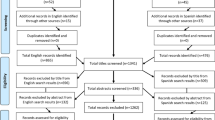

Data Collection & Analysis

To ensure sufficient variation among the participants, age, gender, disability, income, residence, and family status were considered when recruiting older and family interviewees (Heller et al., 1990). The focus groups’ numbers were subject to preset criteria (Table 3), older population distribution, and local communities’ referrals. With street communities’ assistance, participants were recruited from different neighbourhoods to guarantee a fair distribution.

Economic sustainability and social inclusiveness are key pillars in Yichang due to a significant proportion of ethnic minorities and a proposed national PPP integrated-care demonstration programme. This means low-income and ethnic minorities are two major parameters for the implementation of focus-group study in this city. By contrast, the seaport city Ningbo has a more developed economy with an influx of migrants: therefore, higher income and older migrants have become major indicators in the study. Focus-groups interviewees in both cities covered residential/home/community-based care receivers.

Table 4 presents the profile of 382 participants distributed across age, gender, dependency, income, minority and/or migration in the two cities (171 in Yichang; 211 in Ningbo). Overall, 20% more females than males were involved, including family representatives to reflect different generations’ voices towards eldercare services. The 8 ethnic minority representatives in Yichang (mainly Tujia, Hui, and Bai), and the 10 older migrants in Ningbo (mostly due to resettlement) were intentionally included.

Focus-group interviews were held with preset guide questions (from general to specific) in different districts of Yichang and Ningbo. All participants had the opportunity to talk about their past experiences, present perceptions, and future expectations of eldercare services. For instance, we asked the following questions: What was learned from previous engagement in eldercare services? What are the current strengths/weaknesses and possible challenges/suggested changes to eldercare services? How can eldercare services be enhanced in the future? What about the sustainable future of eldercare services?

Due to the overlapping participants of two focus groups in each city, 42 focus-group interviews were completed in total. For each focus-group session, two researchers were involved: a moderator (asking questions) and an observer (taking notes), as recommended by Heller and other scholars (1990). All questions were asked in Mandarin but repeated in local dialects by an additional helper if participants were not fluent Mandarin speakers. Notes were taken in Chinese/English, while data was input into excel sheets and double-checked by both researchers to ensure its reliability. Anonymity of all the respondents was guaranteed, through full confidentiality of their identity and no disclosure of any personal details. The datasheet only contains the information relevant to this research.

Focus-group interviews generated rich qualitative data in the literal form. With such translation-interpretation processes, content analysis (Heller et al., 1990) and thematic approach (Rabiee, 2004) occurred simultaneously during the ‘interplay between researchers and data’ (Strauss & Corbin, 1998, as cited in Rabiee, 2004, p.657). Based upon continuous reflections and sequential analyses, themes and patterns were identified through comparing/contrasting data and cutting/pasting similar quotes together (Rabiee, 2004). Nevertheless, the analytical focus was to assess theme-based pattern-matching and needs-prediction of sustainable eldercare services in both cities.

The main themes, surrounding the choice of care options were drawn from the development of codes, categories, and concepts throughout the analytic process. Following these parameters, various patterns of older adults were identified. Regarding the public, private, or semi-public care models, there were benchmarking eldercare practices in both cities.

Findings—Eldercare Service Perceptions and Expectations

The findings of this study offer significant insights into the participants’ experiences and perceptions of integrated-care, which comprises residential-, home-, and community-care, as well as further understanding of care demands, as presented in Table 6. The study has identified seven patterns of older adults in China, taking into consideration their lifespan changes, with particular attention to their personal circumstances and professional experience, as summarised in Table 7. Particular attention has been given to the existing supply of eldercare services by different institutional arrangements, to evaluate possible future sustainable scenarios.

Integration-Based Findings

Overall, the participants in both cities were open to eldercare options. While only a quarter of focus-group interviewees in Yichang was willing to accept the idea of living in a care home, about three-fourths of focus-group attendees in Ningbo expressed their willingness to consider residential care. Despite such a gap, a common view held by the two city participants (especially older interviewees) was that a residential-care solution would be finally chosen unless one was ‘physically or psychologically vulnerable’ and had ‘no family members’. In other words, older adults would prefer to stay at home with community support if they could live independently. Whilst family care was valued, Table 5 reveals some major concerns behind such preferences that appear more prominent in Yichang, as confirmed by both individual and institutional focus-group interviewees.

Municipal civil affairs officials added that older adults’ lifestyle in Yichang was still strongly influenced by traditional Chinese culture: since ‘family’ and ‘home’ are still of the utmost value in Chinese society, 80% of them would have preferred to spend their entire old age at home because care homes might limit their freedom; they were reluctant to change their living environment and life habits, and many of them could not afford residential care. Although residential care through ‘care homes’ has been gradually accepted, informal care and homecare have all been successfully integrated whilst community care has also become popular nowadays.

The views expressed about eldercare services through focus-group interviews varied across generations, reflecting the differences determined by life-cycle factors such as age, health, income, education, occupation, and family status (Table 6). In Yichang, 60–70 participants showed their willingness to ‘accept residential care’ when being ‘fragile’ or even ‘still in good health’ but ‘unlikely to have their only-child looking after’ them, because of the ‘one-child policy’.Footnote 4 Those aged 70–80 with 2 + children either sought family support or never thought of formal care. The 80 + older adults often had larger families with more children in the conditions to offer care assistance. However, this outcome could be limited by their children’s newly established family (including grand-children and great-grand-children). In this case, the 80 + older adults had to ‘live alone’ and might desire ‘residential care’ if s/he had sufficient income.

Community-care receivers in Yichang seemed ‘happy with free access to care equipment, such as massage armchairs, health check-ups, activity rooms, and subsidized hairdressing’, but they ‘barely used day-care, library, and computer rooms’ mainly because of ‘the contradictory needs of older adults with different levels of income and education’. The participants noticed that: ‘Those who are still healthy and active do not need day-care whilst those who are seriously ill would seek home-based or residential care instead’. In Ningbo, community-care centres were perceived as ‘offering a much wider range of activities and services’, and ‘day-care was welcomed’ by 10 more participants.

Home-based care receivers were often confused about community-based and residential care services. Most Yichang interviewees demanded ‘more features and functions of healthcare (including Chinese medicine and rehabilitation), activities, meals, therapies’ (e.g., physical, speech, gardening, music). A ‘home-community blending care model’ was proposed by several Ningbo participants. This highlighted a real need for a well-configured community-care infrastructure, with a small proportion of residential-care beds, and extensive medical and life support for home-based care.

The low-income participants were polarized into either relying on ‘family care’ or willing to accept ‘residential and community care’ but with poor affordability. In Yichang, while the middle-income participants showed better eldercare awareness and were willing to pay for ‘fine services’, the low-income participants did not expect ‘meal support’ through the community-care scheme because it was ‘more economical to cook at home’. Those with better educational profiles usually preferred ‘better facilities’ and ‘quality care’.

According to focus-groups’ results in both cities, higher-income participants expected ‘better care facilities with more freedom and privacy’ whilst lower-income participants, normally less educated, seemed to be satisfied with ‘basic care’. The threshold-distinctive expectations were reflected in the high-versus-low income paired within a single city and contrasted across the two cities. Both city participants indicated that ‘with a higher income’ they would be ‘willing to pay extra for additional medical-care and recreational activities’.

Most focus-group participants advocated the concept of ‘integrated-care’. However, a few Yichang attendees raised the issue that a lot of apartments in old communities built in the 1970s-1990s had no elder-friendly facilities, such as elevators or ramps. This situation seemed to be worse in Yichang as Ningbo had carried out elder-friendly residential renovations earlier. Half of Yichang respondents asked for ‘better housing (e.g., a studio or one-bedroom apartment with open or close kitchen area, bathroom, and balcony) with nursing care and life service’, and a combination of residential, home- and community-based care was viewed as a desirable solution.

The participants’ willingness to pay eldercare expenses in both cities highly depends on pension income and service expectations. Most interviewees expressed their willingness to pay ‘50–80% of pension income’ for ‘basic care coverage with appropriate services’. Family members in focus-group interviews expressed ‘respect for their parents’ eldercare choice and willingness to provide financial support if parents do not have sufficient income’ when they could (especially for residential care). Meanwhile, many older participants stated that they had to ‘support their children or sustain daily life without becoming a burden for them’.

Since ‘socially acceptable’ and ‘economically affordable’ are two key terms in previous studies, social inclusiveness is an indisputable perspective in this study.

Inclusion-Based Findings

People across different life cycles have different experiences. Through focus-group interviews, age, health, family, education, income, gender, minority, and migrant were identified as key parameters in eldercare services’ considerations. From the preset criteria to the developed codes and categories, a thematic analysis generated seven patterns of older adults and the relevant care expectations in these two cities (see Table 7) for both present and future.

The Super-Aged Pattern

The 80 + older participants have a higher risk of suffering from physical and/or mental health declines. Most of them usually have many children and have lost their spouse, and thus demand ‘informal care’ when their children reach retirement age, or ‘formal care’ when their children have to cope with their own lives. As soon as the 80 + become left-behind or empty-nest older adults, the ‘retired cadres’Footnote 5 receive ‘preferential treatments’ from the government concerning eldercare and medical-care; those who retired from public service units with good pension income would choose the ‘middle-range residential care’, and a large proportion of older adults retired from enterprises with lower pension income would opt for the ‘low-end care solutions’.

The Educated-Urban-Youth Pattern

With living and working experiences in mountainous and rural areas,Footnote 6 the ‘educated-urban-youth’, mostly between 65 and 80, will soon turn into the super-aged (80 +) pattern. Under the national birth-control policy and the laid-off scheme from many state-owned enterprises, this generation usually has one child only with the typical 4–2-1Footnote 7 family structure. Therefore, they expressed a desire for ‘residential care’ if they ‘become more vulnerable’ and willingness to ‘accept independent living in a facility’. Because of their unusual past engagement, they expected ‘state support for eldercare’ and sought ‘collective, economic care solutions’. More precisely, they wanted ‘a twin or triple room, sufficient activity space, recreational programmes, friendly staff, and medical support’. Consequently, this group should be incorporated for social inclusion by the public and PPP projects.

The Nearly-Retired Pattern

The nearly-retired people at age 50–65 will be the mainstream older adults in the next decade. Compared with the ‘educated-urban-youth’, they also have one child with the typical 4–2-1 family, but they have usually been better educated and earned more as direct beneficiaries from the ‘open-door and reforms policy’ started in 1979. The government civil servants, university teachers, executives, experienced technicians, managers, and entrepreneurs during focus-group interviews shared numerous sparkling ideas about their upcoming retired life and were keen to explore possible care options for their parents and themselves. By contrast, the presentation of nearly-retired managers or technicians from enterprises offered very mixed thoughts. With potentially less pension income but reasonable higher service expectations, they proposed to build ‘a collective platform for mutual care and support’.

The open-minded middle-class cohort had very different eldercare expectations compared with their 80 + older parents. They attached greater attention to ‘facility design, functional configuration, room size, private space, care scope, staff attitude, customer care (e.g., trust, respect, sympathy), and service quality’. What they expected regarding care services for their parents now and for themselves in the future could be attributed to cultural, institutional, and economic shifts.

The Male–Female Pattern

The age of 60 is a dividing line for population distribution by gender. Across age strata, focus-group interviews in both cities showed that above 60 the gender ratio was no longer balanced: the percentage of women significantly increased since women usually live longer than men but, on average, women earn less than men with poorer education. In general, female participants revealed their ‘lonely feelings’ and thus had special needs of ‘emotional companionship and psychological care’, while male attendees simply wanted ‘meal service and healthcare’.

Evidence of gender-related impact (arising from longevity, income, and education) was mainly found in older women. With lower-income, females were more willing to consider eldercare options and more active in seeking community-based activities and social support. Hence, the need to hire ‘counsellors and therapists’ to assist older women at care homes and to schedule regular visits and activities for those at home to make sure they have the right access (equality) to home- and community-based care. Most 80 + older women have no spouses, and as a result, residential care is often a choice for social inclusiveness.

The Complex-Frailty Pattern

The most common chronic diseases for older participants are the same as those listed by the national guide.Footnote 8 Their main challenges are ‘physical vulnerability, feeling lonely, or lacking social networks, children companionship, and community-based activities’ – reported by various focus groups in both cities. ‘Dementia and Parkinson’s disease’ are usually found and discussed in the 80 + older groups, who are in particular need of ‘medical-care’. However, ‘hypertension and arthritis are particularly prominent due to eating habits and sea climate’, and ‘hypotension’ should be considered for ‘nursing-care’ – as emphasized by both professional healthcare and older representatives in Ningbo.

According to stakeholders’ consultations with representatives from both Municipal Disabled Associations, the 60 + older adults with ‘congenital or acquired disabilities, such as mental, visual, physical, hearing, speech, and intellectual disabilities’ should be considered for social inclusiveness. For facility design, ‘Braille and sign language as well as speech therapist, together with Braille tiles, sound and colour’, should be introduced in the architecture, landscape, and room planning – as suggested by stakeholder participants.

The Older-Minority Pattern

The total number of minority older adults in Yichang city is nearly 1500, of which around two-thirds are Tujia and about one-seventh are Hui (YSB, 2020). While official participants said that ‘local government respects the minorities’ religious beliefs and traditional customs (…) Hui, Uygur, and Salar believe in Islam so that these ethnic people desire Halal treatment, Muslim Canteen, and prayers’ rooms’; Tujia, the largest minority of the city’s population, nowadays ‘lives in ways similar to the Han Chinese’ – as observed by the minority interviewees. However, it is important to pay attention to their cultural and ritual activities in designing residential facilities and creating home- and community-based services. Since each minority has its own language, festivals, and customs, similar concerns are raised by the Bai too. This pattern is unique to Yichang and does not apply to Ningbo.

The Older-Migrant Pattern

In Ningbo, a group of 60–85 older participants, poorly educated with little pension income, has resettled from the rural to the urban area. Like the 80 + older adults, they usually have 2 + children, simply ‘wait and see’ for eldercare, and expect their ‘children to act as informal caregivers when in need’. Meanwhile, the inter-provincial (or inter-city) older migrants who had normally retired from other places and then relocated to Ningbo to support their children appeared in some focus groups. They enjoyed life with their children, looking after their grandchildren when they could but will need ‘formal and informal care’ support once their health deteriorates. They were aware of their problematic eldercare future due to their household registration, medical insurance, and lifestyle. Hence, they expected ‘policy integration, local adaptation, and social networking’ at both institutional and individual levels.

The different patterns of older adults revealed by this research reflect the present and future needs of varied care models, with specific characteristics. All these patterns identified from focus-group interviews in the two cities suggest a necessity to refer to institution-based findings of eldercare services.

Institution-Based Findings

In both Yichang and Ningbo, research participants who have been enrolled or engaged in care homes perceive the ‘Municipal Social Welfare Home’ as the ‘residential-care benchmark’. Amongst local citizens and industry workers, this type of state-funded and public-owned care home has a ‘good reputation’ and is seen as ‘the ideal residential-care model with a full range of care services at the right cost of bed rate and service charge’. In the private sector, the Yichang ‘Three Gorges Older Care Home’ residents were satisfied with its ‘hygiene conditions’ and ‘staff attitude’, whilst ‘Guang’an’ was praised as an equivalent facility by the Ningbo focus-group interviewees.

As one of the most popular private residential-care facilities, except for utility bills, the resident’s monthly fee is near twice the social welfare house charges, covering accommodation, meals, and nursing care fees. That’s why ‘people have high hope for PPP’, as stated by the professional care interviewees. There are a few Chinese-style PPP eldercare projects as per stakeholders in Ningbo, but older participants were not familiar with this concept.

According to both care providers and receivers in focus-group discussions, home and community care services in Yichang are ‘under the government subsidy scheme and further complemented by the commercial sector’. The situation is similar in Ningbo, but with slightly more private service providers. The paid home and community care receivers in Yichang are usually 80 + older living alone and in need of daily assistance. The typical home- and community-based care packages in Yichang are ‘very basic’ such as ‘meal preparation and cleanup’, whist the corresponding care scope in Ningbo is much wider at a much higher fee. Most participants said they ‘had got used to the system’ since they ‘learnt to cope with the living environment’. They were happy with the stipulated range of care services in each city and expected ‘an extended scope of healthcare with safety and quality endorsement by local authorities’. The interviewees in Yichang were looking forward to ‘integrated-care services’ from the selected PPP sites, and those in Ningbo spoke very highly of the ‘Vanke-type of embedded-care centres’.

More prominently, participants with less income and a lower professional profile declared their ‘poor affordability’ and expected ‘free admissions or governmental support from the public and PPP care providers’. On the contrary, those with higher income and higher professional profiles have higher expectations that can be fulfilled by the middle-range to high-end care operators in the private sector. This was evident from the Yichang low-incomer versus the Ningbo high-incomer focus group discussions as well as other relevant focus-group participants in both cities.

The two governments have had various plans to develop more eldercare facilities but for private investors, Ningbo is more attractive than Yichang, according to stakeholder participants. In addition to economic concerns, local governments need to plan integrated-care at a strategic level with supportive policies. As emerged from focus-group discussions in Yichang, there is a potential for ‘integrated-care providers to offer catering and caring services to both facility and neighbourhood residents’. It is feasible to bring the best social and institutional support to all older adults as further confirmed by participants in Ningbo.

However, a series of inclusion programmes for women, minorities (ethnic and migrant), disabled, and empty-nested older adults with minimum guarantees or low-income are anticipated from the public and PPP programmes. The question remains if there is a sustainable paradigm of eldercare services in China.

Discussion—Sustainable Future of Eldercare Services

To ensure continuous satisfaction among stakeholders and future eldercare sustainability in a city, the integration of eldercare ought to comprise a broad spectrum of formal and informal, health and lifecare services through family, institutional, and technological settings. This overall result responds to various scholars’ call for the integration of eldercare services in home, community, and care facilities with smart technology (e.g., Zhou, 2019). However, one’s final choice of eldercare does partially depend on one’s living arrangements, as stated by the UN (2020), which explains why homecare is acknowledged as the primary care model in both cities.

Based upon both direct and combined variables (Rajan et al., 2020), this study indicates that the fundamental priority for eldercare concerns in the two selected cities is health; the second is family status, and the third is income. Family status (with or without a spouse or children) matters when making decisions in seeking residential, community- or home-based care, whilst eldercare expectations and decisions are very much dependent on one’s disposable income. As to the residential-care choice, age, closely linked with health and family status, such as the ‘80 + empty-nest older adults’ with health concerns, plays a vital role. Broadly speaking, certain participants’ reluctance to accept residential care was generally due to their good-health conditions. However, in Yichang, such reluctance was also due to their poor perception of the existing care facilities’ quality. This explains why Yichang requires an increase and improvement of care supply, while Ningbo demands more ‘premium care’ due to its sufficient eldercare supply and medical-care integration. In both cities, care homes’ provision of medical- and nursing-care is expected by all participants, most of whom had a desire for health-life care services (Özsungur, 2020) in integrated contexts. The future-led ‘nearly-retired’ cohort expressed more desire for the integration of the different care settings with smart tech support, which is likely to drive the change of eldercare services in the long run. The sustainability of eldercare services by ‘further integration’ of different types of care services has been raised both in Yichang and Ningbo. Nevertheless, through this study, many older participants did not seem to be aware of what smart care exactly means and implies. Certainly, the social-technical factors, such as the user-friendly design with mature technologies for care robots (Pekkarinen et al., 2020), should not be ignored to advance the effectiveness of smart care. However, the question of whether the users, especially the super-aged adults and poorly educated people, are ready for the so-called smart care should be fully understood by policymakers and addressed by service innovators (see Svensson et al., 2021).

Age and gender notwithstanding, income, education, and occupation are tightly associated. The educational and occupational background of care receivers and family members does not merely have an impact on their total income and affordability in general, but it also affects their final eldercare solutions because of their learning and working experience. The expectations of the low-versus-high profile retirees on eldercare services vary from threshold to distinctive level. It was observed that the Ningbo focus-group representatives’ average income is much higher than those in Yichang: Yichang’s middle-incomers are those with an annual income of RMB50,000 and above whilst in Ningbo this category earns a lot more. In Yichang, low-incomers and those living on minimum subsistence allowances are simply concerned with ‘poor affordability’. These findings further suggest the need for integration of a range of low-medium–high eldercare offers, and the necessity to consider price in care services and ‘poverty’ in Yichang, in particular.

In allocating financial resources, supporting parents for eldercare was not the priority for most family representatives. On the contrary, the older adults’ willingness to access care services should not bear any additional cost for their offspring. This reveals the traditional parent-children’s perception of ‘filial piety’ and ‘mutual aid’, which influences their spectrum of willingness-to-pay for eldercare services and might be different from family regimes in other cultures (see Hrast et al., 2020).

The future needs for eldercare services are highlighted by the ‘nearly-retired’ and the ‘educated-urban-youth’ (close to the ‘baby-boom generations’ born from the late 1940s to mid-1960s) who are quite sensitive to the cost–benefit issue. They are keen to include housekeeping and healthcare, viewing ‘cleaning and cooking’ as ‘compulsory’ in residential care but ‘supplementary’ in community- and homecare, ‘medical- and nursing-care as ‘core’ in residential care but ‘support’ for community- and homecare, ‘social-networking and recreational-activities’ as ‘added-value’ within residential care but ‘very necessary’ for community care. More specifically, Chinese medicine, therapy, and rehabilitation are expected for all types of care models, whilst ‘telemedicine and telecare’ are proposed for community- and homecare. In addition, the high-profile expect better facility design and configuration, privacy and decorations, quality, and customer care, while the low-profile want catering and caring arrangements.

All this supports the need for ‘disparities’ in product, price, place, promotion, people, process, and physical evidence between high and low-income older adults across the two cities, with Ningbo being more ‘polarized’ in the future needs of eldercare services. Among the varied care demands, healthcare (see Özsungur, 2020) is indeed the most important element of eldercare services. Meanwhile, Chinese people may long for some additional care functions and service features with Chinese characteristics such as Chinese medicine and collective-oriented activities.

The gender, minority, frailty parameters and patterns further suggest that female, minority, and migrant older adults are eager for equal treatments, culturally sensitive, disabled-friendly social care and professional expertise. This confirms that for women, minorities, and migrants, ‘equal access’ to the right care services (product, place, physical evidence, and people) is equally important. Furthermore, attention to the ethnic minority (in Yichang) and older migrants (in Ningbo) is essential in building inclusive, resilient human settlements for safe, sustainable city communities. The equality and multi-cultural issues have been essentially echoed in researchers’ views about European eldercare studies (e.g., Gavanas, 2013). In particular, the desires and needs of migrant/minority older adults and migrant caregivers should be addressed with attention to cultural and institutional considerations.

According to the integration, inclusion, and institution-based analysis, it is feasible to draw an 8P model for the eldercare service mix present and future (Table 8). The matrix summarises how the different parameters and patterns of older adults could shape the health and life needs of older adults, through the 8P support. Whilst the 7P healthcare mix (Chana et al., 2021) helps define eldercare services in general, the concept of ‘partnership’ can arguably inform care provisions, service innovation, and total quality as a complementary mechanism suitable to respond to a mixture of social-cultural, economic, demographic, behavioural, physiological, and psychological factors in the Chinese ageing society.

As Busse et al. (2003) argue, the type of services is determined by a complex interaction of various supply and demand factors (e.g., morbidity rates, population structures, income levels, social-cultural, and behavioural factors). On the one hand, the choices of eldercare services are decided by people influenced by one’s personal/professional profile, health/life scenario, and cultural/institutional beliefs. On the other hand, physical evidence, service bundle, and fee scheme would play an important role, being partially framed by the institutional process of market arrangements and multidisciplinary partnerships across the public and private domains.

For instance, the dichotomy between the ‘open-minded nearly-retired’ and the ‘educated-urban-youth’ presents very different eldercare expectations because of their different life circles—even though they share similarities in the 4–2-1 family structure with one child only. Through a selection of welfare (planning) and commercial (marketing) eldercare services, the former could gain access to better quality services whilst the latter might have more economic options that certainly leverage the social value of inclusiveness. Those who have neither property nor proper income, if they are enclosed for social inclusiveness, the ‘older adults living on minimum subsistence allowances’Footnote 9 could be entitled to free or partial payment of care options subject to health assessment. The gap between an eligible person's actual income and care costs may be covered by local government in the public or state-funded or PPP projects. Significantly, ‘partnership’ is a response to market forces (Zheng et al., 2020) and social inclusion concerning the integration of eldercare services.

To adapt to the constant change of supply–demand scenarios, Yichang has been active to promote its PPP integrated-care project to its citizens as it is important to reinforce the elder-centric logic. Furthermore, human capital, referring to professionals, patients, and payers, has been considered one of the most significant determinants of adaptive capacity for the healthcare revolution (Ćwiklicki et al., 2020). Since ‘people (caregivers) serve people’ (care-receivers) is the structural backbone of care services, ‘people’ assumes a fundamental relevance in this industry. For instance, if the caregivers are familiar with the receiver’s traditions and language, the older adults’ (people) care experiences will be greatly enhanced.

The emphasis on ‘People’, in the long-term delivery of eldercare, partially confirms Schiavone and Ferretti’s (2021) forecast on an integrated user-centric humanised healthcare future, while the emphasis on ‘Partnership’ is critical to the continuing development of care services. Therefore, we argue that ‘people’ and ‘partnership’ are the two crucial elements to guarantee sustainable delivery of eldercare services in the future. These 2Ps pave the way for poverty and inequality alleviation and could be the drivers for quality improvement and social prosperity in the local ageing community.

Conclusion

This study stems from the assumption that care support for older adults is a crucial determinant of the selected five SDGs, which are in turn associated with personal, social, and institutional factors. However, eldercare services should adapt to local demand, culture, and institutions. To improve the long-term sustainability of eldercare services, cross-institutional synergy from both public and private spheres is crucial. Even though both Yichang and Ningbo are expected to enhance the integration of eldercare services, Yichang should increase both quantity and quality of future supply whilst Ningbo should improve the total quality of care services.

After presenting the current and future needs of care services for the various patterns of older adults in the two selected Chinese cities, the authors conclude that the emerging trends of sustainable eldercare are a combination of public and private, and/or semi-public/private, institutions that can support integration of residential, community, and home care with the ready-to-use technology, to accommodate the needs of the various groups of older adults. To beat the benchmark, care homes should have appropriate rooms’ typology and design configurations with ‘GP, geriatric, therapy, rehabilitation, and recreational functions’, especially when launching a national demonstration PPP programme as a strategic solution.

The comparative analysis of eldercare expectations and perceptions in Yichang and Ningbo, allowed the authors to demonstrate a series of consistent but somewhat divergent ageing issues and the relevant care solutions that have arisen in Chinese urban society. Although the details of service integration, the targets of social inclusiveness, and the schemes of institutional partnership must address the particular structure and features of the local ageing population, this study brings to the fore a Chinese perspective of eldercare which is interrelated with the local circumstances.

The past-present-future/supply–demand/perception-expectation theorizing analysis offers a feasible methodological approach to understanding and redefining the context-specific eldercare sustainability. Built upon the universal but unique elements of 8Ps for care services, the article offers a conceptual model for the sustainable development of eldercare services. Theoretically, the development of the 8P model contributes to the scholarship dominated by McCarthy’s 4Ps’ product marketing since the 1960s and Boom and Bitner’s 7Ps’ service marketing since the 1980s (Rafiq & Ahmed, 1995).

More specifically, ‘partnership’ provides useful insights into the sustainability of eldercare for the future creation of an inclusive, prosperous, sustainable community in China. The design of ‘partnership’ must vary from city to city, based on the specific situation of each locale, taking into consideration both ‘people’ (care professionals, caregivers, and care recipients) and inclusiveness considerations. The emphasis on ‘people’ and ‘partnership’ offers a groundbreaking foundation for better integration and inclusion of services formulation. Eventually, the 8P might provide a necessary reference framework for future eldercare studies, from both local and global perspectives. Furthermore, the use of 8Ps could universally promote future eldercare services according to the UN’s sustainable goals.

Notes

According to the hierarchical classification of Chinese cities, Tier-1 cities are the largest, densely populated, and wealthiest urban metropolises with the highest economic, cultural, and political influence, while Tier-3 cities are small-scale provincial capital cities and/or prefecture-level cities.

Cp. World Health Organisation (WHO) and ‘The Law of the PRC’s on the Protection of Rights and Interests of Older People’, 1996, 1st edition; 2018, 3rd revision.

Their parents are usually 80 + . For further information regarding the official retirement age in China, cp. GUO FA [1978] 104 Document – ‘Interim Measures’ on ‘Retirement and Resignation of workers’ and ‘The Resettlement of Old, Weak, Sick, and Disabled Cadres’ issued by the State Council, PRC.

The ‘One-Child Policy’ in China was introduced in September 1980 and lifted in January 2016.

Those who made special contributions to the country’s emancipation – under the cadre quota.

The ‘Sent down’ policy began on 9th August 1955.

A couple who has four parents (2 parents and 2 parents-in-law) and one child.

Hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, arthritis, obstructive pneumonia, asthma, dementia, depression, and Parkinson’s.

With monthly income below RMB680 per person or twice that per household (YSB, 2020).

References

Bergman, M. A., Johansson, P., Lundberg, S., & Spagnolo, G. (2016). Privatization and quality: Evidence from elderly care in Sweden. Journal of Health Economics, 49, 109–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2016.06.010

Booms, B. H., & Bitner, M. J. (1981). Marketing strategies and organization structures for service firms. In J. H. Donnelly, & W. R. George (Eds.), Marketing of services (pp. 47–51).

Busse, R., Wurzburg, G., & Zappacosta, M. (2003). Shaping the Societal Bill: Past and future trends in education, pensions and healthcare expenditure. Futures, 35, 7–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-3287(02)00047-2

CDRF. (2020). China’s Development Plan: Ageing Population: China’s Development Trend and Policy Options. China Development Press.

Chana, P., Siripipatthanakul, S., Nurittamont, W., & Phayaphrom, B. (2021). Effect of the service marketing mix (7Ps) on patient satisfaction for clinic services in Thailand. International Journal of Business, Marketing and Communication, 1(2)(13), 1–15.

Connolly, D., Garvey, J., & McKee, G. (2017). Factors associated with ADL/IADL disability in community-dwelling older adults in the Irish longitudinal study on ageing (TILDA). Disability and Rehabilitation, 39(8), 809–816. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2016.1161848

Ćwiklicki, M., Klich, J., & Chen, J. (2020). The adaptiveness of the healthcare system to the fourth industrial revolution: A preliminary analysis. Futures, 122(2020), 102602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2020.102602

Gavanas, A. (2013). Elderly Care Puzzles in Stockholm: Strategies on formal and informal markets. Nordic Journal of Migration Research, 3(2), 63–71. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10202-012-0016-6

Gjellebak, C., Svensson, A., Bjorkquist, C., Fladeby, N., & Grunden, K. (2020). Management Challenges for Future Digitalization of Healthcare Services. Futures, 124(2020), 102636. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2020.102636

Gonzalez-Jimenez, H. (2018). Taking the Fiction out of Science Fiction: (Self-aware) Robots and What They Mean for Society, Retailers and Marketers. Futures, 98, 49–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2018.01.004

Grudinschi, D. et al. (2013). Management Challenges in Cross-Sector Collaboration: Elderly Care Case Study. Innovation Journal, 18(2). Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258455438. Accessed May 2, 2021.

Heller, K. E., Crockett, S. J., Merkel, J. M., & Peterson, J. M. (1990). Focus-group Interviews with Seniors. Journal of Nutrition for the Elderly, 9(4), 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1300/J052v09n04_07

Hrast, M. F., Hlebec, V., & Rakar, T. (2020). Sustainable Care in a Familialist Regime: Coping with Elderly Care in Slovenia. Sustainability, 12(20), 8498. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208498

Hyman, M. R., & Sierra, J. J. (2016). Focus-group interviews. Business Outlook, 14(7), 1–9.

Institute of Gerontology. (2016). Report on China Longitudinal Ageing Social Survey. Renmin University of China.

Isa, F.M., Noor, S., & Syazwan, M.A. (2020). Exploring the facet of elderly care centres in multi-ethnic Malaysia. PSU Research Review. https://doi.org/10.1108/PRR-05-2020-0013.

Johansen, F., & Bosch, S. V. D. (2017). The Scaling-up of Neighbourhood Care: From Experiment towards a transformative movement in healthcare. Futures, 89, 60–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2017.04.004

Kalisz, D. E., Khelladi, I., Castellano, S., & Sorio, R. (2021). The Adoption, Diffusion & Categorical Ambiguity Trifecta of Social Robots in e-Health – Insights from Healthcare Professionals. Futures, 129(2021), 102743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2021.102743

Klakegg. S. et al. (2020). CARE: Context-awareness for elderly care. Health and Technology, 11(4). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12553-020-00512-8.

Lapidus, J. (2019). Half-Private Elderly Care in The Quest for a Divided Welfare State Sweden in the Era of Privatization. Palgrave MacMillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-24784-3

Martín Palomo, M. T., Zambrano Álvarez, I., & Muñoz Terrón, J. M. (2020). Intersecting vulnerabilities. Elderly care provided in the domestic environment. Cuadernos de Relaciones Laborales, 38(2), 269–288. https://doi.org/10.5209/crla.70890

Montfort, C., Sun, L., & Zhao, Y. (2018). Stability by change - the changing public-private mix in social welfare provision in China and the Netherlands. Journal of Chinese Governance, 3(4), 419–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/23812346.2018.1522733

NBS. (2020). China Statistical Yearbook, 2020. Retrieved from http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj. Accessed May 1, 2021.

NBS. (2021). The 7th National Census Report. Retrieved from http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/sjjd/202105/t20210512_1817336.html. Accessed Aug 19, 2021.

NSB. (2020). Ningbo Statistical Yearbook 2020. Beijing: China Statistics Press. Retrieved from http://vod.ningbo.gov.cn:88/nbtjj/tjnj/2020nbnj/zk/indexch.htm. Accessed Aug 19, 2021.

NSB. (2021). The 7th Ningbo Municipality National Census Report. Retrieved from http://tjj.ningbo.gov.cn/art/2021/5/17/art_1229042825_58913572html. Accessed Aug 19, 2021.

Özsungur, F. (2020). Service Innovation in Elderly Care. In H. Babacan, M. Eraslan, & A. Temizer (Eds.), Academic Studies in Social Sciences (pp. 589–608). Ivpe Cetinje.

Pekkarinen, S., et al. (2020). Embedding Care Robots into Society and Practice: Socio-Technical Considerations. Futures, 122(2020), 102593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2020.102593

Rajan, S.I., Shajan, A., & Sunitha, S. (2020). Ageing and Elderly Care in Kerala. China Report, 56(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/0009445520930393.

Rabiee, F. (2004). Focus-group interview and data analysis. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 63(4), 655–660. https://doi.org/10.1079/PNS2004399

Rafiq, M., & Ahmed, P. (1995). Using the 7Ps as a generic marketing mix: An exploratory survey of UK and European marketing academics. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 13(9), 4–15. https://doi.org/10.1108/02634509510097793

Ray, S.K. (2019). Impact of Public-Private Partnership on Efficacy of Health Care Delivery Services. Journal of Global Public Health, 1(1): 35–37. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344991496. Accessed Jan 29, 2021.

Ronnqvist, D., Wallo, A., Nilsson, P., & Davidson, B. (2015). Employee Resourcing in Elderly Care. In S. Bohlinger, U. Haake, C. H. Jorgensen, H. Toiviainen, & A. Wallo (Eds.), Attracting, Recruiting and Retaining the Right Competence in Working and Learning in Times of Uncertainty Challenges to Adult, Professional and Vocational Education (pp. 131–141). Sense Publishers.

Schiavone, F., & Ferretti, M. (2021). The Futures of Healthcare. Futures, 134(2021), 102849. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2021.102849

Schwiter, K., Berndt, C., & Truong, J. (2018). Neoliberal austerity and the marketisation of elderly care. Social & Cultural Geography, 19(3), 379–399. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2015.1059473

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Sage Publications, Inc.

Svensson, A., Bergkvist, L., Bäccman, C. & Durst, S. (2021). Challenges in implementing digital assistive technology in municipality healthcare, In Ekman, P., Keller, C., Dahlin, P. & Tell, F. (Eds.). Management and Information Technology in the Post-Digitalization Era, Routledge.

Szebehely, M. (1996). ‘Om omsorgochomsorgsforskning’ (About care and nursing research), in Omsorgens Skiftningar. Begreppet, vardagen, politiken, forskningen (The shifts of care. The concept, everyday life, politics research), ed. R Eliasson, Studentlitteratur Lund, pp. 21– 35.

UN. (2015). Sustainable Development, 17 Goals to Transform Our World. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment. Accessed July 6, 2021.

UN, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. (2020). World Population Ageing 2020 Highlights: Living arrangements of older persons. (ST/ESA/SER.A/451). Retrieved from https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/news/world-population-ageing-2020-highlights. Accessed July 6, 2021.

Wagiman, A., Mohidin, H. H. B., & Ismail, A. S. (2016). Elderly Care Center. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 30(2016), 012008. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/30/1/012008

Ying, Z., Sang, Y., Zhu, J., Chen, Y., & Zhang, J. (2019). A Study into the Eldercare Service System with Targeted Measures based upon Population Characteristics. Policy Study Center, MCA2019MZZY03–11, PRC.

YSB. (2020). Yichang Statistical Yearbook 2020. Beijing: China Statistics Press. Retrieved from http://tjj.hubei.gov.cn/tjsj/sjkscx/tjnj/gsztj/ycs/202101/P020210112572324105686. Accessed Aug 19, 2021.

YSB. (2021). The 7th Yichang Municipality National Census Report. Retrieved from http://epaper.cn3x.com.cn/sxrb/content/202106/30/c185011.html. Accessed Aug 19, 2021.

Zhang, Q., Li, M., & Wu, Y. (2020). Smart home for elderly care: Development and challenges in China. BMC Geriatrics, 20, 318. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01737-y

Zheng, X. H., Lu, K., Yan, B. Q., & Li, M. Y. (2020). Current Situation of Public-Private Partnership Development for the Elderly in China. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 8, 165–179. https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2020.83015

Zhou, G. T. (2019). The Smart Elderly Care Service in China in the Age of Big Data. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1302, 042008. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1302/4/042008

Acknowledgements

This work is an ongoing project of ‘A Study into the Eldercare Service System with Targeted Measures based upon Population Characteristics’ supported by the Ministry of Civil Affairs, PRC [grant number MCA20190229].

The authors would like to thank Mr Chen Yaqing of Ningbo Municipal Zhejiang Healthcare & Eldercare Development & Research Institute and Mr Zhang Aiping of Yichang Municipal Finance Bureau for their support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Marinelli, M., Zhang, J. & Ying, Z. Present and Future Trends of Sustainable Eldercare Services in China. Population Ageing 16, 589–617 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12062-022-09372-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12062-022-09372-8