Abstract

Semantic paradoxes like the liar are notorious challenges to truth theories. A paradox can be phrased with minimal resources and minimal assumptions. It is not surprising, then, that the liar is also a challenge to minimalism about truth. Horwich (1998/1990) deals swiftly with the paradox, after discriminating between other strategies for avoiding it without compromising minimalism. He dismisses the denial of classical logic, the denial that the concept of truth can coherently be applied to propositions, and the denial that the liar sentence expresses a proposition, but he endorses the denial that the liar is an acceptable instance of the equivalence schema (E). This paper has two main parts. It first shows that Horwich’s preferred denial is also problematic. As Simmons (1999), Beall and Armour-Garb (2003), and Asay (2015) argued, the solution is ad hoc, faces a possible loss of expressibility, and is ultimately unstable. Finally, the paper explores a different combination of possibilities for minimalism: treating the truth-predicate as context-dependent, rejecting the notion that the liar expresses a proposition, and reinterpreting negation in some contexts as metalinguistic denial. The paper argues that these are preferable options, but signposts possible dangers ahead.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Horwich (1998/1990, pp. 2–3).

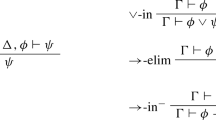

For a good discussion on whether classical negation is compatible with a use-theoretic account of meaning, see Kürbis (2015).

(Horwich 1998/1990, p. 72)

See Horwich (1999, p. 72).

Soames (1999), for instance, took this as a motivation to argue that truth is a partially defined predicate. Another, perhaps less tempting, reaction, is to take the reasoning as showing what it seems to show: that indeed \(\langle \)(1) is not true\(\rangle \) is both true and not true as dialetheists assume. Several of the various options available are thoroughly explored in Field (2008). Many alternatives are not available to Horwich. On numerous occasions, he rejects the option of giving up classical logic or Bivalence because of non-referring terms (Horwich 1998/1990, p. 78), of vagueness (Horwich 1998/1990, p. 79), or of semantic paradoxes like the liar.

Not all conceptual impossibilities are “semantically induced”. “Semantically induced” means that they arise, as in the present cases, from semantic notions or concepts, or are caused specifically by semantic indeterminacy or underdetermination.

I’m grateful to an anonymous reviewer for pointing out the need to elaborate on the reply.

Thanks to another anonymous reviewer for insisting on the clarification of this point.

(Horwich 1998/1990, 72).

I’ll use “make a statement” and “express a proposition” interchangeably for present purposes.

Notice however that the reason why (23) is a FA is that the context of its use does not provide the required salient object of the ostensive demonstration. The failure to make a statement is explained by the semantics for ‘this’.

I argued against using paradoxes as a reason to stipulate, or introduce, the semantic ambiguity of negation in [Author2008; Author2010].

For a discussion of affixal negation, see for instance Horn (2001, Sect. 5.1).

Ripley (2011) points to other problems that arise for the idea that negation and denial are separate independent phenomena.

In fact, in the first footnote of his paper, Kripke says “I have chosen to take sentences as the primary truth vehicles not because I think that the objection that truth is primarily a property of propositions (or “statements”) is irrelevant to serious work on truth or to the semantic paradoxes...Occasionally we may speak as if every utterance of a sentence in the language makes a statement, although below we suggest that a sentence may fail to make a statement if it is paradoxical or ungrounded”(Kripke 1975, fn 1).

It is worth noting that Sorensen (2001) denies Lewis’s insight that truths must supervene on what exists, and defends the claim that there are truths with no truthmakers, i.e., that there are truthmaker gaps. I briefly discuss this below at the end.

Lewis further develops the principle in Lewis (2001).

References

Asay, J. (2015). Epistemicism and the liar. Synthese, 192(3), 679–699.

Ayer, A. J. (1935). The criterion of truth. Analysis, 3(1/2), 28–31.

Barker, S. J. (2000). Is value content a component of conventional implicature? Analysis, 60(267), 268–279.

Beall, J. C. (2001). A neglected deflationist approach to the liar. Analysis, 61(270), 126–129.

Beall, J. C., & Armour-Garb, B. (2003). Should deflationists be dialetheists? Noûs, 37(2), 303–324.

Beall, J. C., & Armour-Garb, B. (2005). Deflationism and paradox. In J. C. Beall & B. Armour-Garb (Eds.), Deflationism and paradox. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Carnap, R. (1937). The logical syntax of language. London: K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Ltd.

Carston, R. (1996). Metalinguistic negation and echoic use. Journal of Pragmatics, 25, 309–330.

Carston, R. (1998). Negation, ‘presupposition’ and the semantics/ pragmatics distinction. Journal of Linguistics, 34, 309–350.

Craig, E. (1985). Arithmetic and fact. In I. Hacking (Ed.), Exercises in analysis. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Field, H. (1986). The deflationary conception of truth. In G. MacDonald & C. Wright (Eds.), Fact, science and morality (pp. 55–117). Oxford: Blackwell.

Field, H. (1994). Deflationist views of meaning and content. Mind, 103(411), 249–285.

Field, H. (2001). Saving the truth schema from paradox. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 31(1), 1–27.

Field, H. H. (2008). Saving truth from paradox. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Geurts, B. (1998). The mechanisms of denial. Language, 74(2), 274–307.

Goldstein, L. (2000). A unified solution to some paradoxes. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 100(1), 53–74.

Goldstein, L. (2001). Truth-bearers and the liar—a reply to Alan Weir. Analysis, 61(2), 115–126.

Herzberger, H. G. (1970). Paradoxes of grounding in semantics. Journal of Philosophy, 67(6), 145–167.

Horn, L. (2001). A natural history of negation (Reissue ed.). CSLI.

Horwich, P. (1998). Meaning. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Horwich, P. (1998/1990). Truth (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Horwich, P. (1999). The minimalist conception of truth. In S. Blackburn & K. Simmons (Eds.), Truth. Oxford University Press.

Horwich, p. (2005). A minimalist critique of Tarski on truth. In J. C. Beall & B. Armour-Garb (Eds.), Deflationism and paradox (pp. 75–84). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Horwich, P. (2008). Being and truth. Midwest Studies in Philosophy, 32(1), 258–273.

Horwich, P. (2010). Truth-meaning-reality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kaplan, D. (1989). Demonstratives. In J. Almog, J. Perry, H. K. Wettstein, & D. Kaplan (Eds.), Themes from Kaplan. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kennedy, C., & McNally, L. (2005). Scale structure and the semantic typology of gradable predicates. Language, 81(2), 1–37.

Kürbis, N. (2015). What is wrong with classical negation? Grazer Philosophische Studien, 92, 51–86.

Kripke, S. A. (1975). Outline of a theory of truth. Journal of Philosophy, 72(19), 690–716.

Lewis, D. (1980). Index, context, and content. In Philosophy and grammar (pp. 79–100). Dordrecht: Reidel.

Lewis, D. (1999). Armstrong on combinatorial possibility. In Papers in metaphysics and epistemology (Vol. 2, pp. 196–214). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lewis, D. (2001). Truthmaking and difference-making. Noûs, 35(4), 602–615.

Lewis, D. (1998). Papers in philosophical logic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Parsons, T. (1984). Assertion, denial, and the liar paradox. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 13(2), 137–152.

Peacocke, C. (1999). Being known. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Quine, W. V. (1970/1986). Philosophy of logic. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Ramsey, F. P. (1927). Facts and propositions. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 7(1), 153–170.

Ripley, D. (2011). Negation, denial, and rejection. Philosophy Compass, 6(9), 622–629.

Simmons, K. (1999). Deflationary truth and the liar. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 28(5), 455–488.

Soames, S. (1999). Understanding truth. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sorensen, R. (1988). Blindspots. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sorensen, R. (2001). Vagueness and contradiction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stalnaker, R. (1978). Assertion. Syntax and semantics (Vol. 9, pp. 315–332). New York: Academic Press.

Stalnaker, R. (2002). Common ground. Linguistics and Philosophy, 25(5–6), 701–721.

Stalnaker, R. (2014). Context. New York: Oxford University Press.

Strawson, P. F. (1950). Truth. Aristotelian Society Supplementary, 24, 111–172.

Tappenden, J. (1999). Negation, denial, and language change in philosophical logic. In D. Gabbay & H. Wansing (Eds.), What is negation? (pp. 261–298). Berlin: Springer.

Tarski, A. (1936). The concept of truth in formalized languages. In A. Tarski (Ed.), Logic, semantics, metamathematics (pp. 152–278). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Valor Abad, J., & Martínez Fernández, J. (2009). A failed “cassatio”: Goldstein on the liar. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 109, 327–332.

Williamson, T. (1994). Vagueness. London: Routledge.

Wittgenstein, L. (1994/1922). Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (Trans. Pears & McGuinness). London: Routledge.

Acknowledgements

I’m very grateful to Joe Ulatowski and to Cory Wright; I’m also grateful to José Martínez, Jordi Valor, Manuel García-Carpintero, and to Peter Sullivan, for the discussion of some of the problems covered in this paper. This work was supported by an FP7 Marie Curie Action, Grant Agreement Number: PIEF-GA-2012-622114; Grup de Recerca Consolidat en Filosofia del Dret, 2014 SGR 626, AGAUR de la Generalitat de Catalunya; project About Ourselves FFI2013-47948-P, Spanish Ministry for Economy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Marques, T. This is not an instance of (E). Synthese 195, 1035–1063 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-016-1293-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-016-1293-8