Abstract

In the first year of the twentieth century, in Gottingen, Husserl delivered two talks dealing with a problem that proved central in his philosophical development, that of imaginary elements in mathematics. In order to solve this problem Husserl introduced a logical notion, called “definiteness”, and variants of it, that are somehow related, he claimed, to Hilbert’s notions of completeness. Many different interpretations of what precisely Husserl meant by this notion, and its relations with Hilbert’s ones, have been proposed, but no consensus has been reached. In this paper I approach this question afresh and thoroughly, taking into consideration not only the relevant texts and context, as others have also done before, but, more importantly, Husserl’s philosophy, his intuition-based epistemology in particular. Based on a system of clearly defined concepts that I here present, I reinforce an interpretation—definiteness as a form of syntactic completeness—that has, I believe, some advantages vis-à-vis alternative interpretations. It is in conformity with the available texts; it makes clear that Husserl’s notion of definiteness is indeed close to Hilbert’s notions of completeness; it solves the important problem of imaginaries for which it was created; and last, but not least, it fits naturally into Husserl’s system of concepts and ideas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

There is no consensus on what Husserl meant by definiteness or what exactly was the relation of his and Hilbert’s notions of completeness related to his axioms of completeness, a relation that Husserl believed should be obvious to all.

Initially, Husserl had the idea of basing more general concepts of number on the notion of cardinal number, favoring, that is, a genetic, bottom-up approach. This was the project for the second volume of Philosophy of Arithmetic (Husserl 2003), which never saw the light of day for, supposedly, Husserl realized that this could not be done. He, then, turned to the axiomatic, top-down approach [see, for instance, Husserl (1970a, p. 378) , where general arithmetic is characterized as a formal science]. Husserl axiomatic approach to set theory of 1891 (Husserl 1970a, pp. 385–407) and geometry of 1893 (Husserl 1983, pp. 285–293), where he shows how the fundamental concepts and truths of axiomatic geometry, such as congruence, are grounded on intuition) show how much involved with the axiomatic method the early Husserl was [see Centrone (2010) for a careful historical account of the philosophical development of the early Husserl and Ortiz Hill, in Hill and Silva (2013, pp. 93–114), for the role Husserl allowed to the axiomatic method in his approach to arithmetic]. For the purposes of this paper, however, this discussion is irrelevant; Husserl’s notion of definiteness, which is a property of axiomatic systems, is without doubt part of his treatment of the axiomatic method, particularly in its complex relations with intuition.

“Dieser [i.e. Hilbert’s] Begriff der Vollständigkeit soll als unechte [my emphasis] Vollständigkeit bezeichnet werden.” (Husserl 1970a, p. 442). I translate “unecht” as “inauthentic”, but it can also be translated as “false”, “artificial”, “counterfeit”, in short, inadequate.

Awodey and Reck (2002) and Corcoran (1980), for example, who follow with care the appearance and maturing of certain logical notions, categoricity and completeness in particular, in early efforts of axiomatization from Dedekind onwards, completely ignore Husserl and his work on axiomatics. This is to some extent understandable, since Husserl did not produce a mathematically relevant pioneering axiomatization that made its way into the mainstream of mathematical logic. But philosophically it is an error to ignore him, for Husserl was probably the philosopher better equipped to provide the correct interpretation of the axiomatic method advanced by Hilbert and himself, much better than the “game” interpretation that gained prominence [see, for instance, Hill and Silva (2013), in particular chapters 3 and 5, and Silva (2012, pp. 115–136)].

“Above all it was its [i.e. arithmetic’s, my note] purely symbolic procedural techniques, in which the genuine, original insightful sense seemed to be interrupted and made absurd under the label of the translation through the ‘imaginary’, that directed my thoughts to the significance and to the purely linguistic aspects of the thinking – and knowing – processes and from that point on forced me to general ‘investigations’ which concerned universal clarification of the sense, the proper delimitation, and the unique accomplishment of formal logic” (Husserl’s draft introduction to Logical Investigations apud Moran 2005, 90). There is, then, a direct link between the problem of “imaginaries” and the Logical Investigations and further attempts of clarification and delimitation of formal logic; for example, Formal and Transcendental Logic.

For details and references see Awodey and Reck (2002).

Mahnke (1923) uses terms that were translated by “logically isomorphic” and “formally equivalent” to refer to the relation between contentual theories and their formalizations, derived for metamathematical purposes (he mentions consistency proofs).

Vide Shoenfield pp. 87–88.

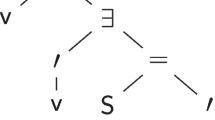

In order to show that 4) implies 2) I assume from the start that a theorem of deduction is valid for the calculus; i.e. if \(\mathrm{T}, \upvarphi \vdash \uppsi \), then \(\mathrm{T} \vdash \upvarphi \rightarrow \uppsi \), for any sentences \(\upvarphi \) and \(\uppsi \).

For Husserl, purely formal (i.e. non-interpreted) axiomatic systems are theory-forms, that is, forms of theories, whose objective correlates are formal manifolds determined as to form but indeterminate as to (material) content. Hence, for him, formal theories belong to formal ontology, the province of formal logic concerned with the formal properties of objects, conceived exclusively as such and merely as possibilities.

From Hilbert’s On the Concept of Number, in Ewald (1996, pp. 1092–93).

This is certainly true if logical consistency implies the existence of interpretations (for example, in first-order logic). For if a system is categorical but not d-complete, one can obtain two consistent extensions of it, a particular sentence belonging to one and its negation to the other. If they both have interpretations, one has a contradiction; the same sentence being true in one interpretation but false in another, both interpretations, however, being isomorphic to each other.

See Husserl (1970a, p. 382), where after claiming that arithmetic is, by general consensus, an a priori science, he says that “darin liegt, dass sie nicht mit singulären Tatsachen beginnt, um sich durch Induktion zu wahrscheinlichen Allgemeinheiten zu erheben, sondern alsbald mit gewissen, und zwar apodiktisch gewissen und unmittelbar evidenten Allgemeinheiten, die sie durch blosse Vergegenwärtigung gewisser ,Grundbegriffe’ und die auf dem Wege mittelbarer Evidenz und Gewissheit alle weiteren Sätze der Wissenschaft liefern”. In short, a priori theories do not begin with induction but conceptual intuition, from where they proceed by the way of logic alone. See also Husserl (1984, Sect. 13) and Husserl (1994, p. 37).

See e.g. Husserl (1984, Sect. 8), where Husserl says that “after mathematicians [...] have formalized their work , they proceed pure mechanically [...]” (ibid, 26); see also ibid, 32. As for the secondary literature, see, for example, Ortiz Hill’s ”Husserl on Axiomatization and Arithmetic”, in Hill and Silva (2013, pp. 93–114) .

Likewise Husserl, Hilbert gave conceptual intuition a fundamental role in mathematical axiomatics. In metamathematics, however, one is allowed to take axiomatic systems as intuition-free “games” with symbols.

See his Was sind und was sollen die Zahlen, of 1888.

See Husserl (1970a, pp. 441–442).

By “domain” I here mean the intended interpretation or, more specifically, its universe, the collection of objects falling under the concept the theory is designed to scrutinize. Husserl often uses this term (Gebiet) in a slightly different sense, as the collection of objects the theory explicitly or implicitly requires to exist. We must keep this ambiguity in mind. The concept of relative definiteness applies to either conception of domain.

Since we know from the start to which domain the theory refers, to capture it descriptively (categorically) can only be a means to an end, namely, to describe it exhaustively (completely).

Dedekind, of course, did not come up with a d-complete theory, but he did not know that and we can conjecture that he believed he had attained this ideal.

Gödel, a thinker influenced by Husserl, also believed so. For him, the independence of certain assertions concerning set theory (given its d-incompleteness) could be overcome by a better intuition of its ruling concept, that of set (the incompleteness of the theory, however, as he himself had shown, can never be completely overcome). Gödel took very seriously Husserl’s notion of conceptual intuition and its role in axiomatics.

A priori non-interpreted axiomatic systems, those that do not have intended interpretations, are an altogether different matter. For Husserl, as already mentioned, they belong to formal ontology, that part of logic that cares about the form with which object in general can present themselves to us.

I am supposing a logical context in which a theory can be consistently extended by the adjunction of sentences that are logically independent of the theory.

I find this observation relevant to understand the heuristic role of mathematical manipulations in purely mathematical extensions of empirical theories, the famously called “unreasonableness” of mathematics in empirical science.

“Eine axiomatisch definierte Mannigfaltigkeit kann die Eigenschaft haben, da\(\upbeta \) jedes ihrer Objekte operativ bestimmbar ist, und zwar eindeutig. D. h. jedes Objekt, das für sie als existierend definiert ist (in die Sphäre der Existenz gehört, welche die Axiome umschreiben), ist durch die zugrunde liegenden oder eine endliche Zahl willkürlich anzunehmender bestimmter Existenzen unmitteelbar oder mittelbar zu bestimmen, und zwar eindeutig. Eine solche Mannigfaltigkeit ist eine mathematische und ist definit (d.h. ihr Axiomensystem ist definit). [...] Relativ definit ist ein Axiomensystem, wenn es zwar für sein Existentialgebiet keine Axiome mehr zulä\(\upbeta \)t, aber es zulä\(\upbeta \)t, da\(\upbeta \) für ein weiteres Gebiet dieselben und dann natürlich auch neue Axiome gelten. Neue Axiome, denn die blo\(\upbeta \) alten Axiome bestimmen ja nur das alte Gebiet. Relativ definit ist die Sphäre der ganzen, der gebrochenen Zahlen, der rationalen Zahlen, ebenso der diskreten Doppelreihenzahlen (komplexen Zahlen). Absolut definit nenne ich eine Mannigfaltigkeit, wenn es keine andere Mannigfaltigkeit gibt, welche dieselben Axiome hat wie sie (alle zusammen). Kontinuierliche Zahlenreihe, kontinuierliche Doppelzahlenreihe” (Schuhmann and Schuhmann 2001, pp. 101–102).

A mathematical domain is one in which all the elements that exist are obtained as the closure of a basis of given elements by some set of operations. The idea is close to our notion of a freely generated structure.

Gauthier (2004, p. 124) also denies that by definiteness Husserl meant categoricity. He believes, however, that what was meant was semantic completeness. From my point of view, he is not so off the mark, but since I think Husserl clearly operates with a syntactic notion of deduction, syntactic completeness is, I believe, the correct reading.

“Durch die und die Axiome ist das Gebiet bestimmt und altere gelten nicht”, Husserl (1970a, p. 442).

“Die Objekte des Gebietes formal durch neue Bestimmungen definiert sein können”, Husserl (1970a, p. 442).

“Wir fragen nun also, ob es Axiomensysteme gibt, die keine Schliessungsaxiom enthalten und doch, nämlich aufgrund ihrer besonderen Natur, es jedem Satz ansehen lassen, ob er in die Sphäre ihrer Deduktion nach Wahrheit und Falschheit gehört”.

“Beschränk definit oder relativ definit = definit im bisherigen Sinn—absolut definit: (1) Relativ definit ist ein Axiomensystem, wenn jeder nach ihm sinnvolle Satz in Beschränkung auf sein Gebiet entschieden ist. Absolut definit ist ein Axiomensystem, wenn jeder nach ihm sinnvolle Satz überhaupt entschieden ist. Also ist absolut definit = vollständig in Hilbertschen Sinn. (2) Wenn nicht nur für die Objekte des Gebietes kein Axiom hinzugefügt werden kann (das durch schon gegebene Axiome Sinn erhält), sondern wenn überhaupt kein Axiom hinzugefügt werden kann. (3) Darin liegt aber, dass die Mannigfaltigkeit (das Gebiet) nicht so zu erweitern ist, dass für das erweiterte dasselbe Axiomensystem gilt wie für das alte.” (Schuhmann and Schuhmann 2001, p. 103).

Compare with the interpretation I advanced above of Husserl’s claim that another manifold cannot exist with the same theory of an absolutely definite manifold.

“Multiplicity means properly the form-idea of an infinite object-province for which there exists the unity of a theoretical explanation or, in other words, the unity of a nomological science” (Husserl 1969, p. 95).

Husserl (1970a, p. 432).

Husserl (1970a, pp. 439–440).

“Ein Durchgang durch die Imaginäre ist gestattet: (1) wenn das Imaginäre sich in einem konsistenten umfassenden Deduktionssystem formal definieren lässt und wenn, (2) das ursprüngliche Deduktionsgebiet formalisiert die Eigenschaft hat, dass jeder in dieses Gebiet fallende Satz entweder aufgrund der Axiome dieses Gebietes wahr oder aufgrund derselben falsch, d.i. mit den Axiomen widersprechend ist“ (Husserl (1970a, p. 441)).

References

Awodey, S., & Reck, E. H. (2002). Completeness and categoricity. Part I: Nineteenth-century axiomatics to twentieth-century metalogic. History and Philosophy of Logic, 23, 1–30.

Centrone, S. (2010). Logic and philosophy of mathematics in the early Husserl, synthese library (Vol. 345). Dordrecht: Springer.

Corcoran, J. (1980). Categoricity. History and Philosophy of Logic, 1(1), 187–207.

da Silva, J. J. (2000). Husserl’s two notions of completeness, Husserl and Hilbert on completeness and imaginary elements in mathematics. Synthese, 125, 417–438.

da Silva, J. J. (2012). Away from the facts. Symbolic knowledge in Husserl’s philosophy of mathematics. In A. L. Casanave (Ed.), Symbolic knowledge form Leibniz to Husserl, studies in logic (Vol. 44). London: College Publications.

Ewald, W. (1996). From Kant to Hilbert: A source book in the foundations of mathematics (Vol. I and II). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Gauthier, Y. (2004). Husserl and the theory of multiplicities mannigfaltikeitslehre. In R. Feist (Ed.), Husserl and the sciences (pp. 121–127). Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press.

Hartimo, M. H. (2007). Towards completeness: Husserl on theories of manifolds 1890–1901. Synthese, 156, 281–310.

Hilbert, D. (1971). Foundations of geometry (L. Unger, Trans. from the tenth German edition). La Salle, Ill: Open Court.

Hill, C. O. (1995). Husserl and Hilbert on completeness. In Hintikka (Ed.), From Dedekind to Gödel, Synthese Library vol 251, Dordrecht: Kluwer. (Reprinted from Husserl and Frege. Meaning, objectivity, and mathematics pp. 179–198, by C. O. Hill & G. Rosado Haddock, Chicago, Illinois: Open Court.

Hill, C. O., & da Silva, J. J. (2013). The road not taken. On Husserl’s philosophy of logic and mathematics, texts in philosophy (Vol. 19). London: College Publications.

Husserl, E. (2003 [1887–1901]). Philosophy of Arithmetic, Psychological and Logical Investigations with Supplementary texts from 1887–1901, D. Willard (Ed.), Kluwer, Dordrecht.

Husserl, E. (1970a [1890–1901]). Philosophie der Arithmetik, mit ergänzenden Texten (1890–1901), Hua XII, L. Eley (Ed.), Martinus Nijhoff, Den Haag.

Husserl, E. (1994 [1905]). Husserl an Brentano, 27. III. 1905, Briefwechsel, Die Brentanoschule I. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Husserl, E. (1984 [1906/1907]). Einleitung in die Logik und Erkentniss-theorie, Vorlesungen 1906/07, Hua XXIV, U. Melle (Ed.), Martinus Nijhoof, Dordrecht, trans. by Claire Ortiz Hill, Introduction to logic and theory of knowledge. Dordrecht: Springer, 2003.

Husserl, E. (1970b [1954, 1936]). The crisis of European sciences and transcendental phenomenology (Vol. Ill). Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

Husserl, E. (1983 [1886–1901]). Studien zur Arithmetik und Geometrie (1886–1901), I. Strohmeyer (Ed.), Husserliana (Vol. XXI). The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

Husserl, E. (1994). Edmund Husserl collected works, Vol. V (R. Bernet, Ed., D. Willard, Trans.). Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Husserl, E. (1970c [1900-01]). Logical investigations (J. N. Findlay, Trans. from the German Second Edition of Logische Untersuchungen), New York: Routledge.

Husserl, E. (1969) [1929]. Formal and transcendental logic (D. Cairns, Trans.). The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

Mahnke, D. (1977 [1923]). From Hilbert to Husserl: First introduction to phenomenology, especially that of formal mathematics’, trans. D. L. Boyer. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science, 8(1), 71–84.

Majer, U. (1997). Husserl and Hilbert on completeness: A neglected chapter in early twentieth century foundations of mathematics. Synthese, 110, 37–56.

Moran, D. (2005). Husserl, founder of phenomenology. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Okada, M. (2013). ’Husserl and Hilbert on completeness and Husserl’s term rewrite-based theory of multiplicity’, invited talk. In 24th international conference on rewriting techniques and applications (RTA’13), Eindhoven, June 2013.

Schuhmann, E., & Schuhmann, K. (2001). Husserls Manuskripte zu seinen Göttinger Doppelvortrag von 1901. Husserl Studies, 17, 87–123.

Shoenfield, J. R. (1967). Mathematical logic. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

da Silva, J.J. Husserl and Hilbert on completeness, still. Synthese 193, 1925–1947 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-015-0821-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-015-0821-2