Abstract

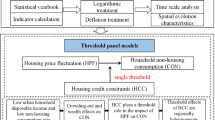

It is important to investigate the correlation between housing price and household consumption to gain an understanding of the behavior of the economy and effectively handle the consequences of economic development. In the last two decades, the accumulation of housing wealth by Chinese households has not been effectively transmitted to their final consumption. We discovered that the sustained increase in household wealth and housing-ownership rate in China has been accompanied by a decrease in consumption rate. We also identified a negative correlation between housing price and household consumption for both the homeowners who own one housing unit and those who own two units of housing. We investigated this phenomenon in China both theoretically and empirically by capturing the dual nature of housing as a consumption good and an investment vehicle. We found that the demand for second housing units is motivated by increasing housing consumption demand rather than pure investment needs. To explain the mechanisms that drive household-consumption behavior, we also explored the effects on household consumption of China’s educational system, marriage market and ageing society, as well as future housing-market uncertainty. The implications of government intervention in the housing market are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The remaining proportion of GDP (51.6% in 1978 and 64.02% in 2012) comprised investment by industries rather than households. It is difficult to account for the contribution of personal housing investment to GDP.

The mean value of urban residents’ financial assets is RMB112,000, and their mean housing assets are 8.3 times greater, according to the 2011 Chinese Household Financial Investigation Report, which was funded by the Southwestern University of Finance and Economics.

In this case, housing investment and housing consumption are separable. Rising housing prices are not expected to alter stock. Instead, households can directly adjust their level of housing investment.

Sebastien (2010) proved that the indivisibility of housing consumption from housing investment leads to a suboptimal composition of household consumption.

Many other studies of the asset-pricing model have highlighted the role of the share of housing consumption, which is referred as “composition risk” by Piazzesi et al. (2007).

Beijing, Chengdu, Dalian, Guangzhou, Hangzhou, Hefei, Lanzhou, Ningbo, Shenzhen, Shenyang, Wuhan and Xian.

Hukou refers to a household-registration record that officially identifies an individual as a resident of a given area. it is one of China’s most important institutions, as it defines individuals’ socio-economic status and access to welfare benefits.

We also estimate the regression for renters only, and find a significant correlation between price and consumption. However, the process of renting involves tenure choice, which is not modeled in our theory and is not our focus of the study.

In Betermier’s (2010) study, homeowners with characteristics extremely similar to those of unconstrained owners are considered to be constrained homeowners. We also test for this case, and obtain fairly consistent results.

We believe that families inclusive of children at primary and middle school are especially eager to live close to schools; high-school children often take buses to school or live in school dormitories. According to Chinese policy, males of 25 years old are in the later period of marriageable age.

We estimate the regression with an “unmarried female child” variable and find no significant results.

On April 17, 2010, the State Council issued the “New 10 Articles,” which were designed to drive speculative demand out of the market. The new measures set down-payments for first mortgages at 30% of purchase price, increased down-payments and interest rates for purchases of second and third homes, and housing purchases by those who are not local city residents are restricted.

No data are available for people who purchased more than one unit. More data are required to draw conclusions regarding homeowners’ purpose in purchasing multiple housing units.

According to mass-media reports, many broker companies are arranging “masculine and feminine elements contracts” and “individual transactions” to evade the regulations. See http://house.focus.cn/news/2013-04-12/3127019.html and http://365jia.cn/news/2011-05-12/8353A4921118AFFA.html.

References

Aron, J., & Muellbauer, J. (2000). Personal and corporate saving in South Africa. World Bank Economic Review, 14(3), 509–544. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/14.3.509.

Attanasio, O.P., Weber, G. (1994). Is consumption growth consistent with intertemporal optimization? Evidence from the consumer expenditure survey (No. w4795). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Belsky, E. (2004). Housing wealth effects: Housing’s Impact on wealth accumulation, wealth distribution and consumer spending. Joint Center for Housing Studies, National Association of REALTORS, Harvard University.

Betermier, S. (2010). Essays on the consumption and investment decisions of households in the presence of housing and human capital. UC Berkerley.

Bover, O. (2005). Wealth effects on consumption: Micro-econometric estimates from the spanish survey of household finances. Working Paper, No. 0522.

Browning, M., & Lusardi, A. (1996). Household saving: Micro theories and micro facts. Journal of Economic Literature, 34(4), 1797–1855.

Brueckner, J. K. (1997a). Infrastructure financing and urban development: The economics of impact fees. Journal of Public Economics, 66(3), 383–407. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2727(97)00036-4.

Brueckner, J. K. (1997b). Consumption and investment motives and the portfolio choices of homeowners. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 15(2), 159–180.

Bucciol, A., & Miniaci, R. (2011). Household portfolios and implicit risk preference. Review of Economics and Statistics, 93(4), 1235–1250.

Campbell, J. Y., & Cocco, J. F. (2007). How do house prices affect consumption? Evidence from micro data. Journal of Monetary Economics, 54(3), 591–621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2005.10.016.

Case A, Deaton A. (2003). Consumption, health, gender, and poverty. World Bank Publications.

Cauley, S., Pavlov, A., & Schwartz, E. (2007). Homeownership as a constraint on portfolio allocation. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 34(3), 283–311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-007-9019-9.

Chamon, M., & Prasad, E. (2010). Why are saving rates of urban households in China rising? American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 2(1), 93–130.

Chen, J. (2006). Re-evaluating the association between housing wealth and aggregate consumption: New evidence from Sweden. Journal of Housing Economics, 15(4), 321–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhe.2006.10.004.

Cocco, J. F. (2005). Portfolio choice in the presence of housing. Review of Financial Studies, 18(2), 535–567. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhi006.

Duca, J. V., & Whitesell, W. C. (1995). Credit cards and money demand: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 27(2), 604–623.

Fan, Y., Yavas, A. (2017). How does mortgage debt affect household consumption? Micro Evidence from China. SSRN Working Paper, No. 2966987.

Fan, Y., Wu, J., & Yang, Z. (2017). Informal borrowing and home purchase: Evidence from urban China. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 67, 108–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2017.09.003.

Feng, H., & Lu, M. (2010). School quality and housing prices: Empirical evidence based on a natural experiment in shanghai, China. The Journal of World Economy, 12, 89–104 (In Chinese.)

Flavin, M., & Nakagawa, S. (2008). A model of housing in the presence of adjustment costs: A structural interpretation of habit persistence. The American Economic Review, 98(1), 474–495.

Flavin, M., & Yamashita, T. (2002). Owner-occupied housing and the composition of the household portfolio. The American Economic Review, 92(1), 345–362. https://doi.org/10.1257/000282802760015775.

Hansen, L. P., & Singleton, K. J. (1983). Stochastic consumption, risk aversion, and the temporal behavior of asset returns. Journal of Political Economy, 91(2), 249–265. https://doi.org/10.1086/261141.

Haurin, D. R., Hendershott, P. H., & Kim, D. (1991). Local house price indexes: 1982–1991. Real Estate Economics, 19(3), 451–472. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6229.00562.

Heckman, J.J. (1979). Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 153–161.

Henderson, J. V., & Ioannides, Y. M. (1983). A model of housing tenure choice. American Economic Review, 73(1), 98–113.

Huang, Y. Q., & Yi, C. D. (2010). Consumption and tenure choice of multiple homes in transitional urban China. International Journal of Housing Policy, 10(2), 105–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616718.2010.480852.

Ioannides, Y. M., & Rosenthal, S. S. (1994). Estimating the consumption and investment demands for housing and their effect on housing tenure status. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 76(1), 127–141. https://doi.org/10.2307/2109831.

Jud, D. G., & Seaks, T. G. (1994). Sample selection bias in estimating housing sales prices. Journal of Real Estate Research, 9(3), 289–298.

Ko, P.C., Hank, K. (2013). Grandparents caring for grandchildren in China and Korea: Findings from CHSRLES and KLoSA. Journal of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Science and Social Science.

Kraft, H., & Munk, C. (2011). Optimal housing, consumption, and investment decisions over the life cycle. Management Science, 57(6), 1025–1041. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1110.1336.

Liao, L., Huang, N., & Yao, R. (2010). Family finances in urban China: Evidence from a National Survey. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 31(3), 259–279. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-010-9218-z.

Ludwig, A., Slok, T. (2002). The impact of changes in stock prices and house prices on consumption in OECD Countries. IMF Working Paper.

Lustig, H. N., & Van Nieuwerburgh, S. G. (2005). Housing collateral, consumption insurance, and risk premier: An empirical perspective. The Journal of Finance, 60(3), 1167–1219. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2005.00759.x.

Markowitz, H. (1952). Portfolio selection. Journal of Finance, 7, 77–91.

Muellbauer, J., & Murphy, A. (2008). Housing markets and the economy: The assessment. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 24(1), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/grn011.

Munnell, A.H., Soto, M. (2008). The housing bubble and retirement security. Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Palmer, E., Deng, Q. (2008). What has economic transition meant for the well-being of the elderly in China? In inequality and public policy in China (pp. 182–203), edited by B. A. Gustafsson, S. Li.

Piazzesi, M., Schneider, M. (2008). Inflation illusion, credit, and asset prices. In Asset Prices and Monetary Policy (pp. 147–189). University of Chicago Press.

Poterba, J. M. (2000). Stock market wealth and consumption. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 14(2), 99–118. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.14.2.99.

Qiao, K. Y. (2012). Has house purchase limit policy taken effect? Evidence from China 70 upper middle cities. Research on Economics and Management, 12, 25–34 (In Chinese.)

Riley Jr, W. B., & Chow, K. V. (1992). Asset allocation and individual risk aversion. Financial Analysts Journal, 48(6), 32–37.

Samuelson, P. (1970). The fundamental approximation theorem of portfolio analysis in terms of means, variances and higher moments. Review of Economic Studies, 37(4), 537–542. https://doi.org/10.2307/2296483.

Sebastien, B. (2010). Consumption and investment of housing in portfolio. Doctoral thesis at UC Berkeley.

Tanaka, T., Camerer, C. F., & Neuyen, Q. (2010). Risk and time preferences: Linking experimental and household survey data from Vietnam. The American Economic Review, 100(1), 557–571. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.100.1.557.

Wang, X., & Cai, M. C. (2011). Analysis of risk aversion coefficient determination and influencing factors of Chinese residents - empirical study based on Chinese residents to invest in behavioral data. Financial Research, 08, 192–206 (In Chinese.)

Wei, S. J., & Zhang, X. B. (2011). The competitive saving motive: Evidence from rising sex ratios and savings rates in China. Journal of Political Economy, 119(3), 511–564. https://doi.org/10.1086/660887.

Wik, M., Aragie Kebede, T., Bergland, O., & Holden, S. T. (2004). On the measurement of risk aversion from experimental data. Applied Economics, 36(21), 2443–2451. https://doi.org/10.1080/0003684042000280580.

World Bank (1985). World development report, 1985. Washington, DC; New York: Oxford University Press.

Yang, Z., Zhang, H., Chen, J. (2014). How does the motivation of purchasing a second residence affect housing wealth effect: A micro study on basis of urban household survey data. Forthcoming in Finance Analysis. (In Chinese.)

Yang, Z., Fan, Y., & Cheung, C. H. Y. (2017). Housing assets to the elderly in urban China: To fund or to hedge? Housing Studies, 32(5), 638–658. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2016.1228853.

Yao, R., & Zhang, H. H. (2005). Optimal consumption and portfolio choices with risky housing and borrowing constraints. Review of Financial Studies, 18(1), 197–239. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhh007.

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 71673154 and 71461137002). The usual disclaimer applies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

Derivation of the model

In our model, the utility function at time t of a household with life length T (T > 0) is U(Ct, H t ), which is a time-separable and time-invariant utility function describing the household’s preference for housing services (H t ) relative to non-housing goods (C t ). We assume that no bequest motive exists, and that the household consumes all of its remaining wealth in period T. The optimal allocation of consumption and housing is given by the Bellman equation shown below, in which the household arrives at the maximum level of current utility plus the expected discounted value in period t + 1 as a function of future consumption and housing price:

where E is expectation and Wt + 1 is total wealth, including housing wealth, in the period t + 1. H ct is the unit of housing consumption, H it is the unit of housing investment and H t denotes the total housing owned. To simplify the model, we define only one financial asset, S t .

Meanwhile, we assume that the household’s expected housing price in the next stage will reach P t (1 + u h ), where P t is housing price in period t and u h is growth rate. The financial asset S t receives u p per period in profit. The period to period budget constraint incorporates differences in housing-asset value, as follows: P t (H t − Ht − 1). We assume that the household can rent out separate housing investments and obtain rent to optimize household profit, as shown in R t H it , where R t is the rent price per housing unit in period t (Henderson and Ioannides 1983).

Therefore, the budget constraint can be represented as follows:

where Y t is total income and C t is non-housing consumption.

Homeowners who can make separate decisions regarding housing consumption and investment are motivated to consume housing and invest in housing by two distinct mechanisms. These mechanisms can be incorporated into our model. We use the Lagrangian-multiplier method to obtain the first-order extreme conditions, as follows.

Thus, the equation determining H It can be written as follows.

Using the Taylor expansion, we can write \( {V}_{t+1}^{\prime } \) as the following approximate equation.

We can then obtain the following.

var(u h ) is the variance in the expected growth rate of housing price, and indicates individuals’ confidence in the price trend as well as the risks associated with housing investment. A = − V′′/V′, which denotes an individual’s relative risk aversion.

To compare housing-investment decisions with housing-consumption decisions, we rewrite Eq. (7) as follows.

Combining the above equation with Eqs. (5) and (6) gives the relationship between the marginal utility of housing consumption and that of other consumption.

The equation above indicates that the marginal utility of housing consumption and the marginal utility of non-housing consumption are related solely to user cost, assuming that the utility function of households’ consumption is written as follows,

where, ω measures the household’s preference for non-housing consumption relative to housing consumption, and γ is the coefficient of relative risk aversion over the entire consumption basket.

We know that the household’s consumption structure is determined by the following principle:

which suggests that the household’s housing-consumption decisions differ from its housing-investment decisions. Here, ρ is the discount rate of P t .

To address the case of a homeowner for whom housing investment and housing consumption are indivisible, we follow Sebastien’s (2010) general procedure. We assume that the homeowner’s mean-variance utility is as follow:

where, μ w denotes expected future wealth, γ is the risk-aversion constant and σ w is the standard deviation of future wealth.

If the movements of stock and housing are uncorrelated, we can write:

where, σ i is the standard deviation of asset i (which may be housing asset H, financial asset S or future wealth W), α i is the portfolio share and r is the interest rate.

We further obtain that:

where λ s is the Sharpe ratio of asset S.

Maximizing the utility function under the budget constraint determined in Eq. (10), we obtain:

And further,

Substituting all of these results for the homeowner’s utility gives the marginal utility of the ratio of housing.

It is then easy to obtain the opportunity cost, as follows:

where

As discussed in the text, opportunity cost influences the consumption decisions of homeowners for whom the intention to invest in housing is inseparable from the intention to consume housing.

We substitute Eq. (11) for Eq. (12) to give Eq. (3.3) in the text as follows:

Appendix 2

Key Variables in the Empirical Tests

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Z., Fan, Y. & Zhao, L. A Reexamination of Housing Price and Household Consumption in China: The Dual Role of Housing Consumption and Housing Investment. J Real Estate Finan Econ 56, 472–499 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-017-9648-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-017-9648-6