Abstract

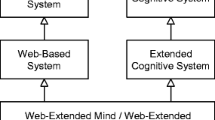

This chapter introduces the theory of the ‘extended mind,’ which holds that human cognition consists of both mental activities occurring in the biological brain in partnership with cognitive technologies outside of the brain. Unlike other species, humans have developed ‘symbolic technologies’ that enable us to engage in cognitive tasks that our biological brain alone would not be able to perform. The Internet represents the next stage in a long historical-evolutionary process whereby humans have expanded cognition via a symbiosis of the brain and a larger system of external, technologically enhanced memory storage.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Preview

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Andy Clark and David J. Chalmers, ‘The Extended Mind,’ in Richard Menary, ed. The Extended Mind (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2010), 27.

For a thoughtful critique of the extended mind hypothesis, see Robert D. Rupert, Cognitive Systems and the Extended Mind (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009).

Mark Rowlands, The New Science of the Mind: From Extended Mind to Embodied Phenomenology (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2010), 3.

Merlin Donald, A Mind So Rare: The Evolution of Human Consciousness (New York: W.W. Norton, 2001), 305.

Colin Renfrew, Prehistory: The Making of the Human Mind (New York: The Modern Library, 2007), 80.

Lambros Malafouris, How Things Shape the Mind: A Theory of Material Engagement (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013), 245.

This term comes from Esther Pasztory by way of Claude Levi-Strauss, who stated, according to Pasztory, that ‘things are good to think with, rather than merely good to look at.’ She writes: ‘It would seem that the thinking process needs projections on and manipulation of things to work itself through to consciousness or to demonstrate itself to itself. In that sense it could be said that [picturing arranging or closet arranging is] a form of magic ritual. I reorganized the world by manipulating symbols. My means were aesthetic (what looked right), but my urgent concern was cognitive (what was right and matched certain sets of data). Things are needed to think with, in order to manage problems of cognitive dissonance.’ Esther Pasztory, Thinking With Things: Toward a New Vision of Art (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2005), 21.

Merlin Donald, Origins of the Modern Mind: Three Stages in the Evolution of Culture and Cognition (Harvard University Press, 1991), 2.

Donald, Origins of the Modern Mind, 199. Steven Pinker has argued that, contrary to a long tradition in linguistics, thought does not equate to language. Indeed, he has posited a quality he calls ‘mentalese,’ thoughts that exist before they are represented in language or any other symbolic system. He observes: ‘We have all had the experience of uttering or writing a sentence, then stopping and realizing that it wasn’t exactly what we meant to say. To have that feeling, there has to be a “what we meant to say” that is different from what we said.’ See Steven Pinker, The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language (New York: Harper Perennial, 1995), 57.

On the relationship between gesture and thought, see David F. Armstrong, William C. Stokoe and Sherman E. Wilcox, Gesture and the Nature of Language (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995);

and David McNeill, Hand and Mind: What Gestures Reveal About Thought (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992).

For an interesting history of the idea of information, see Michael E. Hobart and Zachary S. Schiffman, Information Ages: Literacy, Numeracy, and the Computer Revolution (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998). The authors argue that ‘the invention of writing gave birth to information itself, engendering the first information revolution. Writing created new entities, mental objects that exist apart from the flow of speech, along with the earliest, systematic attempts to organize this abstract mental world.’ (2) It was the action of preserving human thought in material form that constituted ‘information.’ The authors write ‘Both writing and speech constitute communication, but of the two only writing extracts the sounds of speech from their oral flow by giving them visual representation … Because information separates mental objects from the flux of experience, it follows that different information technologies can single out different aspects of experience in different ways, generating different kinds of information’ (4–5). This analysis strikes me as very similar to what Donald was suggesting about the movement toward semantic representation and the creation of the external symbolic storage system. Hobart and Schiffman see writing as the prime mover event in the creation of information, but, as I note above, I see this invention with the first stone figurines and cave paintings. To follow their definition, these were mental objects separated from the flow of experience. However we term it, there was an historical development from evanescent forms of communication that were not preserved in material form versus those that were so preserved.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Copyright information

© 2014 David J. Staley

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Staley, D.J. (2014). Extend. In: Brain, Mind and Internet: A Deep History and Future. Palgrave Pivot, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137460950_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137460950_1

Publisher Name: Palgrave Pivot, London

Print ISBN: 978-1-349-49883-3

Online ISBN: 978-1-137-46095-0

eBook Packages: Palgrave Media & Culture CollectionLiterature, Cultural and Media Studies (R0)