Abstract

Central America has a long history of family formation via consensual union instead of formal marriage. The historically high levels of cohabitation have persisted throughout the twentieth century up to the present day and can be traced in the remarkably high levels of nonmarital childbearing in the region. This chapter reviews past and recent trends in the prevalence of consensual unions in six Central American countries – Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Panama – in order to ascertain whether cohabitation has reached an upper ceiling in the region and whether the apparent stability at the aggregate level conceals significant changes in cohabiting patterns across social groups. The analyses reveal that the expansion of cohabitation has not come to an end so far, largely because of the recent increase in consensual unions among the higher educated strata. The historically negative educational gradient of cohabitation remains largely in place, but differentials in union patterns across countries and across social groups have narrowed considerably in the past two decades.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction

The coexistence of marriages and consensual unions has long been one of the most distinctive features of nuptiality patterns in Latin America (Quilodrán 1999; De Vos 2000; Castro-Martín 2002; Rodríguez Vignoli 2004; Esteve et al. 2012a). This ‘dual nuptiality’ regime, in which formal and informal partnerships – similar in their social recognition and reproductive patterns, but divergent with regard to their stability, legal obligations and safeguard mechanisms – coexist side by side, has been particularly salient in Central America, where high levels of cohabitation have prevailed historically until present times. Whereas in many Latin American countries a trend towards the formalization of conjugal bonds and a consequent decline in consensual unions took place during the first half of the twentieth century (Quilodrán 1999), levels of cohabitation in Central America remained among the highest in the Latin American context. According to census data, the proportion of consensual unions already surpassed that of legal marriages in 1940 among women of reproductive age in Panama; and in the 1970 census round, consensual unions outnumbered formal marriages also in El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras. Therefore, consensual unions have long been the dominant type of conjugal union in the region, well before the ‘cohabitation boom’ that many Latin American countries experienced as of the 1970s and particularly from the 1990s onwards (Esteve et al. 2012a).

Prior studies have documented only minor changes in the prevalence of consensual unions in most Central American countries since the 1970s as well as a downward trend in Guatemala, depicting an overall picture of relative stability around high levels (Castro-Martín 2001). This evolution goes counter to the general upward trend of cohabitation in the rest of Latin America and could suggest the existence of a ceiling to the expansion of informal unions. Hence, it is relevant to examine recent trends and patterns with updated data in order to ascertain whether cohabitation has in fact reached an upper ceiling in the region and whether the apparent stability at the aggregate level conceals significant changes in cohabiting patterns across social groups.

As in the rest of Latin America, consensual unions have been an integral of the family system for centuries (Socolow 2000). Their historical roots can be traced back to pre-Hispanic times and to the early colonial period, when male colonizers, largely outnumbering women, found in the “amancebamiento” a means of sanctioning sexual unions with indigenous women (McCaa 1994). The dual nuptiality system consolidated throughout the colonial period: formal marriage was the norm within the Spanish elite in order to guarantee the intergenerational transmission of property, whereas informal unions were mainstream among the majority mestizo population (Lavrin 1989), resulting in very high proportions of births occurring out of wedlock (Kuzneof and Oppenheimer 1985; Milanich 2002). The Church was only partially successful in imposing the Catholic marriage model on culturally and ethnically mixed societies, and restrictions towards inter-ethnical marriages constituted an additional obstacle. In rural areas, the scarcity of civil and ecclesiastic authorities may also have prevented couples from seeking legal or religious sanction for their unions. Consensual unions, hence, have been commonplace in the region for centuries. Although they had broad social recognition and did not face stigmatization in the past, they were rarely conferred the same social prestige or rights – for instance, in terms of inheritance – as formal marriages.

Besides the legacy of a long historical tradition of cohabitation, persistently high poverty levels and deprived socio-economic conditions among large segments of the population are also part of the explanation for the widespread presence of consensual unions in Central America. Consensual unions were the typical partnership form outside the social elite in the past, and they still remain nowadays the predominant union type among the lower educated and disadvantaged social strata. Not only do the expenses of a wedding celebration pose a significant hurdle for poor couples, but some segments of the population may also feel alienated from the legal system, distrust bureaucratic procedures, or perceive no practical benefits from legal contracts over implicit agreements.

Central America is also known for having a pattern of early sexual initiation, early union formation and early motherhood. As a result, the region displays the youngest age at first union and the highest rates of adolescent fertility in Latin America (Monteith et al. 2005; Lion et al. 2009; Remez et al. 2009). All these factors are associated with a higher likelihood of entering cohabitation instead of marriage (Bozon et al. 2009; Grace and Sweeney 2014). Limited access to reproductive health care and low contraceptive use among the poorest and less educated segments of the population (Stupp et al. 2007; Grace 2010) can also lead to early entry into cohabitation after an unplanned pregnancy (Rodríguez Vignoli 2004).

The widespread presence of consensual unions is clearly reflected in the remarkably high levels of nonmarital childbearing in the Central American region. Vital statistics, although prone to under-registration, indicate that since at least the 1970s more children are born outside the legal framework of marriage than within. Nonmarital births currently represent about 70 % of all births in Costa Rica and El Salvador and around 80 % in Panama (Laplante et al. 2015). A recent study on unmarried childbearing in Latin America based on census data (Castro-Martín et al. 2011) showed that the increase in nonmarital births observed in the 1970–2000 period was mainly attributable to births to cohabiting parents. In this period, the proportion of births to women in a consensual union increased from 19 to 33 % in Costa Rica, although in countries such as Panama, where this proportion was already high in 1970, the increase was minor (from 57 to 59 %).

In this chapter, we will review past and recent trends in the prevalence of consensual unions in six Central American countries – Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Panama – in order to ascertain whether cohabitation levels have remained relatively stable around high levels or whether further increases can be observed in more recent times, as is the case in the rest of Latin America. We will also examine how the prevalence of consensual unions across the age range has changed in past decades. Next, we will address whether differentials in the level of cohabitation across educational strata, which have been traditionally very large, have lessened over time. Given that a recent increase in consensual unions among the highly educated strata has been documented for many Latin American countries (Esteve et al. 2012a), it would be interesting to learn whether the same pattern can be observed in Central America, despite its polarized social structure and its slow pace of social and economic development. Finally, we will compare the socio-demographic profile of married and cohabiting women aged 25–29 in order to identify similarities and differences in labor force activity, reproductive behavior and co-residence patterns by union type.

The analysis is based on census and survey data. For census data, we mainly use the IPUMS files of harmonized census microdata (Minnesota Population Center 2014). All census sources for Central America contain information on current union status, including the category of consensual union (Rodríguez Vignoli 2011). For Panama, six census rounds (1960–2010) are accessible in IPUMS, but for the rest of the Central American countries, either no census microdata are available (Honduras and Guatemala) or only a limited number of census rounds are accessible in IPUMS. Therefore, in order to examine trends and changing patterns over the past five decades for all countries, we also use the REDATAM online system provided by CELADE to process census information, as well as survey data from the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) and the Reproductive Health Surveys (RHS). For Guatemala, we also use the 2011 National Living Conditions Survey. The analysis focuses on current types of partnerships because recent demographic surveys with retrospective union histories, which would allow us to examine the dynamics of the process of union formation, are not available for all countries in the region.

Although the analyses in this chapter are of a descriptive nature and rely on cross-sectional data, they provide compelling evidence of recent increases in cohabitation in most Central American countries and a shift away from marriage among higher educated women, resulting in narrower gaps in the prevalence of consensual unions across countries and across social groups in the region.

2 The Central American Demographic and Social Context

The Central American isthmus, with a total population of nearly 45 million in 2013, over 15 million of whom live in Guatemala, comprises some of the poorest and more rural countries in Latin America. High and persistent levels of poverty and inequality have long characterized the region (Pérez Brignoli 1989; Pebley and Rosero-Bixby 1997). In the last two decades, following a long period of political turmoil, civil unrest and armed conflicts, the Central American economies have begun to recover from the structural and debt crises of the 1980s, and most countries have entered a path of moderate economic growth. Nonetheless, the benefits of economic growth have not yet reached the majority of the population and most Central American countries still lag behind the rest of Latin America with regard to socioeconomic development. As shown in Table 6.1, all countries except Costa Rica and Panama had a GDP per capita well below the average for Latin America in 2013. Concerning social development, the Human Development Index (HDI) – a composite measure of income, life expectancy and education outcomes – also ranks all Central American countries, aside from Costa Rica and Panama, below the average for Latin America (UNDP 2014).

Poverty remains deeply entrenched in the region (CEPAL 2014). About half of the population in El Salvador, Guatemala and Nicaragua, and over two-thirds of the population in Honduras live below the national poverty line. The incidence of extreme poverty – defined as severe deprivation of basic human needs, including food – is highest in Honduras, where it reaches 46 %, well above the average for Latin America (11 %). Although some progress in poverty reduction has been made in the past two decades, advances have been very slow, and rural areas continue to have twice the incidence of extreme poverty than their urban counterparts (Hammill 2007). Progress in inequality reduction has been even more limited. In most countries, the Gini coefficientFootnote 1 remains close to or above 50, a level that denotes a very unequal distribution of income. Guatemala and Honduras not only record the highest levels of poverty but also those of socio-economic inequality. In both countries, the richest 10 % holds about 45 % of all income (UNDP 2014)

This deep-rooted social inequality may hamper the expansion of education across all social groups. Over the past two decades, Central America has achieved important gains in literacy and elementary education. Most countries have already met or are close to meeting the second millennium goal of primary education for all (CEPAL 2010). According to Table 6.1, the net enrollment rate in primary educationFootnote 2 in 2012 was over 90 % for boys and girls in all countries, except in Guatemala and Honduras, where it was somewhat lower. However, the progress made in the area of secondary education has been less than optimal and there remains considerable variation across countries. In 2012, net enrolment rates in secondary education ranged from around 36 % in Guatemala and Honduras to 74 % in Costa Rica. The reduction in disparities of access, continuation in and completion of secondary education, both across and within countries, continues to be a challenge ahead in Central America in order to lessen social inequality and social vulnerability. Other important challenges that the region face are gender inequality (CEPAL 2013), and the highly segmented labor market, with large informal economies where employment is more volatile, pays lower wages and provides no social protection (Hammill 2007).

With regard to demographic trends, most countries in the region are well advanced in their demographic transition, although the poorest countries lag behind. Total fertility rates currently range from 1.8 children per woman in Costa Rica to 3 in Honduras and 3.8 in Guatemala. Despite overall fertility reduction, adolescent fertility remains at very high levels, particularly in Nicaragua and Guatemala (Samandari and Speizer 2010). The prevalence of adolescent fertility is disproportionally higher among disadvantaged women – poor, rural or indigenous – perpetuating the vicious cycle of poverty (Remez et al. 2009). Central America also stands out in the Latin American context for having an early pattern of union formation. According to demographic surveys conducted around 2000, the median age at first union for women was slightly over 18 in Nicaragua and around 19 in Honduras and Guatemala (Monteith et al. 2005). Union disruption and migration – to other Central American countries or to the United States – are also frequent in the region, and are two major factors contributing to the relatively large prevalence of female-headed households, which currently represent nearly one-third of all households in most countries of the region (CEPALSTAT; García and de Oliveira 2011).

3 Current Prevalence of Cohabitation: At the High End of Latin America

Central America, together with the Caribbean, has traditionally exhibited the highest levels of cohabitation in Latin America, and it still maintains this leading position, although the gap with other regions has recently narrowed due to the considerable increase in cohabitation that has taken place in many Latin American countries during the past decade (Esteve et al. 2012a).

Table 6.2 presents the proportion of consensual unions among women aged 15–49 currently in a partnership, according to the most recent census or survey data. The figures attest the widespread presence of unmarried unions in the region. The prevalence of cohabitation among women of reproductive age is highest in Panama, where informal unions comprise about two-thirds of all partnerships, and it is also remarkably large in Honduras and Nicaragua, where consensual unions outnumber formal marriages. A somewhat lower prevalence but nonetheless high is found in El Salvador, Costa Rica and Guatemala, where consensual unions currently represent 49, 40 and 38 % of all partnerships respectively.Footnote 3

Since many consensual unions are short-lived – either because the couple separates or formalizes the union through marriage – current levels of cohabitation measured cross-sectionally in censuses and surveys are typically well below women’s life experience of cohabitation. However, the lack of retrospective survey data for all Central American countries precludes us from using a longitudinal approach to study the dynamics of entry and exit from cohabitation and to estimate the proportion of women who have ever been in a consensual union at any point in their lives. It should also be noted that current levels of cohabitation at the time of the census or survey include second and higher order unions, which are less likely to be legally sanctioned than first unions.

Table 6.2 also presents the current prevalence of cohabitation among partnered women in the age group 25–29, in order to capture primarily first unions and contemporary patterns, as well as to maximize comparability with the rest of the chapters in this book. At that age most women in the region have completed their education and have entered their first partnership. It can be observed that, in this specific age group, the proportion of partnerships built on a consensual basis is above the average for all women of reproductive age, but the ranking of the countries remains unaltered. As before, the highest incidence of cohabitation is observed in Panama (74 %) and the lowest in Guatemala (41 %).

The widespread prevalence of cohabitation in this age group is also confirmed if, instead of focusing only on partnered women, we take into consideration all women regardless of union status (Fig. 6.1). The proportion of all women aged 25–29 who are currently in a consensual union ranges from 26 % in Guatemala to 49 % in Panama. We can also observe a relatively high proportion of women aged 25–29 who declare themselves to be single in countries such as Costa Rica or El Salvador − 37 % and 34 % respectively –, but these proportions are probably overestimated because many women who have experienced a consensual union break-up are likely to report their current conjugal status as single instead of separated (Esteve et al. 2010). There is also a nontrivial proportion of women who declare themselves to be separated or divorced at this relatively young age: in the range of 10–14 % in Honduras, Nicaragua and Panama. In countries with higher rates of union disruption, the mismatch between cross-sectional measures of cohabitation and the true extent of lifetime cohabitation will be larger.

Percent distribution of women aged 25–29 by conjugal status

Note: Countries are sorted in descending order by prevalence of cohabitation.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on the data sources displayed in Table 6.2

4 Spatial Patterns of Cohabitation

Despite generally high levels of cohabitation in the Central American Isthmus, there is a certain degree of heterogeneity not only across countries but also within countries, presumably linked to distinct socioeconomic and cultural factors, as well as ethnic composition. Detailed spatial data at the municipality level based on the 2000 census round are represented in Map 6.1 The share of consensual unions among all partnerships of women aged 25–29 ranges from 5 % in the municipality of Almolonga (department of Quetzaltenango) in Guatemala to 91 % in the municipality of Marale (department of Francisco Morazán) in Honduras. Overall, we can observe strong patterns of spatial clustering within countries, but also across some borders, as in the case of Honduras and Guatemala. In order to understand the spatial patterns of cohabitation, future research would need to examine contextual information on dimensions such as socioeconomic development, social stratification and ethnic composition (López-Gay et al. 2014).

The data represented in the Map 6.1 indicate that the spatial correlation between ethnic composition and cohabitation varies according to ethnic group. In Guatemala, for instance, the areas with lower levels of cohabitation correspond to those with a higher proportion of Mayan population. By contrast, in Costa Rica, the areas with higher levels of cohabitation are located along the Atlantic coast, in the Limón province, which has the largest concentration of Afro-Caribbean and indigenous groups.

5 Trends in Cohabitation Over the Past Five Decades

The widespread presence of consensual unions is not a novelty in Central America. This region, together with the Caribbean, has long displayed the highest levels of cohabitation in the Latin American context (Castro-Martín 2001). Although statistical information is limited for the first part of the twentieth century, census data compiled in early United Nations Demographic Yearbooks record exceptionally high levels of cohabitation for some Central American countries in comparison to the rest of Latin America. The share of consensual unions among partnered women of reproductive age was 59 % in Panama according to the 1940 census, and reached 70 % in Guatemala in the 1950 census. In the 1960s census round, for which data are accessible for all countries, consensual unions outnumbered formal marriages in Guatemala and comprised about half of all unions in Honduras, El Salvador and Panama. A somewhat lower level, but still high, was recorded in Nicaragua (40 %). Costa Rica was the only ‘outlier’ as regards the regional pattern of high cohabitation: according to the 1963 census only 14 % of partnered women aged 15–49 were in informal unions.

Table 6.3 and Fig. 6.2 depict time trends in the prevalence of consensual unions based on a fairly comprehensive list of data sources compiled, which includes censuses and surveys (mainly Demographic Health Surveys and Reproductive Health Surveys) from 1960 to date. Although variation in coverage and quality across different data sources and periods might affect comparisons over time and create some artificial fluctuations, the high degree of consistency of different data collected over close dates and the coherence of the tendencies over time point to the reliability of the evolution portrayed.

Since the 1960s, the evolution in the prevalence of cohabitation has not been uniform across all Central American countries. Most countries have followed a trend characterized by relative stability or moderate increases, but there are also some countries that have undergone a large increase or a substantial decline in the prevalence of unmarried unions over this period. In general, those countries where the share of consensual unions was around half of all partnerships among women of reproductive age in the 1960s, such as El Salvador, Honduras or Panama, have maintained those high levels of cohabitation and, with the exception of El Salvador, have experienced a moderate rise in recent years. By contrast, those countries where the share of consensual unions was below half of all partnerships, such as Nicaragua and Costa Rica, have experienced a considerable expansion of cohabitation. The increase was particularly sharp in the case of Costa Rica, where the share of consensual unions among all partnerships of women in reproductive age rose from 14 % in 1963 to 40 % in 2011. The observed increase was particularly intense from the mid-1990s onwards.

A trend in the opposite direction can be observed in Guatemala, the most populated Central American country. By the mid twentieth century, Guatemala had the highest levels of cohabitation in the region. As mentioned above, consensual unions represented 70 % of all unions among women of reproductive age according to the 1950 census. Afterward, a prolonged downward trend can be observed until the mid-1990s: the proportion of consensual unions nearly halved from the 1964 census to the 1994 census. Two subsequent surveys, the 1998 Demographic and Health Survey and the 2002 Reproductive Health Survey, indicate that the decline in cohabitation levels has recently stalled and the more recent 2011 Living Standards Survey even shows a slight increase. The observed tendency towards higher formalization of unions during the second half of the twentieth century constitutes an exception not only in Central America, but also in the Latin American context, and the underlying causes are intriguing. Guatemala, where about half of the population still lives in rural areas and nearly one-third lives in severe poverty, has experienced a very slow pace of social and economic development. The 36 years of civil war, which dominated the second half of the twentieth century, also caused extensive societal disruption and halted the expansion of education and health programs. The high proportion of indigenous population combined with marked social, economic and political inequality has resulted in a two-tier country where ethnic divides are strongly correlated with geographical location and socio-economic stratification (Hallman et al. 2007). However, despite the common belief that unmarried cohabitation is more frequent among the Mayan groups than among ladinos – the Spanish-speaking non-indigenous or mestizo population–, several studies have documented the opposite pattern (Castro-Martín 2001; Grace and Sweeney 2014). It is possible that increases – albeit small – in age at union formation may have driven the downward trend in cohabitation during the second half of the twentieth century. Another potential explanation is that, in countries with traditionally very high levels of cohabitation largely linked to poverty and low women’s status, the expansion of primary education favors the formalization of partnerships at first, and it is not until the expansion of secondary education to large segments of the population that the tendency to form a consensual union reemerges, although with a different connotation than in the past. In this regard, access and attainment of secondary education is still rather limited in Guatemala and vast inequalities linked to ethnicity, gender, socio-economic status and geography remain: only 23 % of the population over age 25 has at least some secondary schooling (UNDP 2014).

Overall, the diverse trends across countries over the past five decades have led to an increasing convergence of the levels of cohabitation in the region. Since countries with a historically high prevalence of consensual unions have experienced small to moderate increases, while countries with a traditionally low prevalence of consensual unions, such as Costa Rica, have experienced very large increases, past divergences in the levels of cohabitation across neighboring countries have lessened. The singular downward trend in cohabitation observed in Guatemala during the second half of the twentieth century seems to have halted and, since it started off at a very high level, it has also contributed to the increasing convergence in the share of consensual unions in the region, which now hovers in the 40–60 % range.

Figure 6.3 presents analogous time trends in the prevalence of consensual unions for the age group 25–29, in order to capture mainly first unions. The long-term trend patterns (1960–2011) are largely similar to those presented above, but the magnitude of the increase in the more recent period is generally larger when we focus on this young age group. Costa Rica is the country that displays the largest expansion of cohabitation among partnered women aged 25–29 in the past two decades: from 20 % in 1992 to 49 % in 2010. Honduras and Panama have also experienced recent increases in cohabitation after decades of relative stability, and consensual unions currently comprise more than two-thirds of all unions among women aged 25–29. Even Guatemala displays a moderate increase in the share of cohabitation in the most recent years, after several decades of sustained decline. With the exception of El Salvador, all countries have experienced a sizable rise in the prevalence of consensual unions among women aged 25–29 since the turn of the twenty-first century.

In sum, previous studies that examined trends in cohabitation in the Central American region during the second half of the twentieth century described this evolution as characterized by relative stability, with short-term fluctuations around a level that was already high in the 1950s, suggesting that cohabitation in the region might have leveled off (Castro-Martín 2001). Data from the latest surveys and from the 2010 census round indicate that further increases in cohabitation have recently taken place in most countries, and this rise becomes even more evident when we focus on the 25–29 age group, questioning the assumption of stable cohabitation levels in the region.

6 The Age Profile of Cohabitation: A Union Type Not Confined to Youth

The age profile of cohabitation can provide some indications on the underlying dynamics of entry and exit from cohabitation. Figure 6.4 illustrates the prevalence of consensual unions according to women’s age for different time periods in six Central American countries. As expected, the highest incidence of cohabitation corresponds to the youngest age groups. In all countries except Guatemala, informal unions currently outnumber formal marriages until age 30. Consensual unions account for the large majority of partnerships among women under age 20, ranging from 84 % to 95 % in all countries but Guatemala. Their incidence is also very high in the 20–24 age group, reaching over 70 % of all partnerships in Honduras, Nicaragua and Panama. Although cross-sectional data do not allow us to analyze adequately the timing and process of union entry, they suggest that first union formation outside the legal marriage framework is the norm in the region.

The ratio of consensual unions to formal marriages diminishes with age, a pattern that could reflect multiple underlying processes: cohort changes in the rate of entry into cohabitation, a higher preference for marriage among women who delay union formation, a tendency to formalize relationships as women grow older, different rates of separation among married and cohabiting women, and different rates of entry into cohabitation among formerly married and formerly cohabiting women at later ages. These processes cannot be adequately disentangled without longitudinal data. However, although consensual unions become less prevalent at advanced ages, the graphs corroborate that they cannot be accurately portrayed as a type of union confined to youth. The proportion of consensual unions surpasses that of formal marriages among women aged 35–39, and represents around 45 % of all unions among women aged 45–49 in Honduras, Nicaragua and Panama. Some of these consensual unions might be second or higher order unions, which are generally more likely to be informal than first unions. Nevertheless, the fact that cohabitation remains common at later stages of the life cycle suggests that the process of union formalization is not widespread in Central America and that for many women cohabitation represents a surrogate for marriage rather than merely an early stage in the family formation process.

When we read the cross-sectional data cohort wise, in most countries we can observe a decline in the proportions cohabiting over the life cycle, which could reflect a certain tendency to formalize conjugal unions with duration, but the drop observed is relatively moderate. For instance, in Panama, where the prevalence of cohabitation has been relatively stable for the past five decades, the percentage of partnered women in consensual union at ages 20–24 in 1980 was 62 %, and 20 years later in 2000, this percentage drops to 46 % for this female cohort then aged 40–44. Although we cannot ascertain whether these women continue cohabitating with the same partner or a different one, this moderate descent indicates that, for a large segment of the population, cohabitation is not merely a transient state in the pathway to marriage, but a partnership form with long-term expectations.

When data from different periods are compared, in most countries the level of cohabitation has risen moderately across the whole age range over time, but age patterns remain relatively stable, except in the case of Costa Rica, where differences among the younger and older age groups have widened considerably over time, presumably as a result of the sharp rise in cohabitation experienced by younger cohorts since the 1990s. Guatemala also displays a singular pattern: whereas the age profile was nearly flat in the 1970s and 1980s, indicating little variation in the prevalence of cohabitation across the reproductive age range, in 2011 differentials across age groups are more marked, reflecting the recent increase in cohabitation among young cohorts, after decades of a downward trend.

7 Changes in the Educational Gradient of Cohabitation

In Central America, the ‘dual nuptiality’ regime has traditionally mirrored the large economic and social inequalities prevailing in the region. Formal marriage was the rule for the upper social class, whereas consensual unions functioned as a kind of surrogate marriage for those social groups with low education, few economic resources and poor economic expectations (Arriagada 2002). This socioeconomic divide in family formation patterns had led to symbolically associate cohabitation in the region with poverty, gender inequality, and distrust of legal processes.

Social class differentials in the prevalence of cohabitation were indeed extremely marked in the past. In 1960, for instance, the share of consensual unions among partnered women aged 25–29 in Panama was 11 % for those with at least secondary education compared to 64 % for those who had not completed primary schooling. A widely polarized social structure was manifested in very divergent union formation patterns, suggesting that family formation via cohabitation was not always the result of personal choice but largely the consequence of limited economic and social opportunities (García and Rojas 2004). This negative educational gradient of cohabitation persists until today in all Central American countries, although, as we will see next, much more attenuated than in the past.

Education is often used as a proxy for socio-economic status, which is related to property ownership and hence with the perceived need to formalize a conjugal union in legal terms. Education also enhances social mobility and prospective opportunities in life chances, influencing women’s decisions in the domain of family and work. At the same time, education shapes attitudes, values and aspirations, providing women with greater personal autonomy and bargaining power to negotiate conjugal arrangements on the terms they wish (Castro-Martín and Juárez 1995). Therefore, changes in the educational gradient of cohabitation can provide insights not only into the impact of socioeconomic inequalities on union formation patterns but also into the different social meanings attached to cohabitation across social classes.

Although consensual unions were very rare among the upper social classes until the 1980s, a number of studies have documented a recent increase in cohabitation among the better-educated strata in many Latin American countries (Parrado and Tienda 1997; Laplante and Street 2009; Binstock and Cabella 2011; Quilodrán 2011; Esteve et al. 2012a). The rise in cohabitation among highly educated women is at odds with the view of consensual unions as “poor people’s marriages”, linked to economic constraints and low women’s status. It tends to be interpreted as the outcome of value shifts towards greater personal autonomy in decision-making and greater gender equity in family relations, in line with the patterns observed in most European countries (Lesthaeghe 1995, 2010). Below, we will examine whether this important change in the meaning attached to cohabitation has also emerged in Central America.

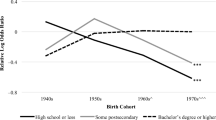

Figure 6.5 illustrates changes in the educational gradient of cohabitation over time in the Central American countries. The graphs represent the proportion of partnered women aged 25–29 currently in a consensual union according to completed educational level for different time periods. It should be noted that cross-sectional data do not allow us to determine to what extent observed differentials among educational groups are due to different probabilities of entering a consensual union or different transition rates from cohabitation to marriage. It should also be taken into account that the social definition of high and low education is subject to change over time. For instance, in Costa Rica, according to the 1963 census, 68 % of women aged 25–29 had not finished primary schooling and only 9 % had completed secondary education or gone beyond. The corresponding percentages for 2011 were 30 and 32 %. Therefore, the expansion of education has made the higher educated strata a less select group. Likewise, women with less than primary education are becoming an increasingly smaller fraction of the population.

We can observe different trend patterns by education across countries. In those countries that have experienced a small or moderate increase in cohabitation since the 1970s, such as El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua or Panama, the prevalence of consensual unions among women with uncompleted primary education has remained relatively stable at very high levels, and the increase in cohabitation has been largely concentrated among women with secondary and higher education. In Panama, during the period 1970–2010, the proportion of partnered women aged 25–29 living in a consensual union increased from 13 % to 72 % among women with completed secondary education and from 0 % to 50 % among women with post-secondary education. In Honduras, during the more recent period 1996–2011, the share of consensual unions increased from 2 % to 35 % among partnered women with post-secondary education, whereas the corresponding increase among women with incomplete primary was only minor: from 70 % to 76 %. In Nicaragua, cohabitation was also exceptional among women with at least secondary education in 1971, but no longer in 2005: consensual unions comprised 41 % of all unions among women with secondary education and 22 % among women with post-secondary education. In El Salvador, recent trends point toward stability in the prevalence of consensual unions among the lower educated groups and a moderate increase in the higher educated groups. On the whole, the educational gradient of cohabitation in all these countries remains negative, but since the increase in consensual unions has been relatively larger among higher educated women, for whom cohabitation was very rare in the past, differentials in union patterns by education have weakened over time.

In the case of Costa Rica, the Central American country that has experienced the largest expansion of cohabitation over the past five decades, the rise in consensual unions has encompassed all educational strata. Back in the 1960s, the presence of consensual unions was relatively marginal in the higher educated strata, but also in the lower educated strata, in contrast to its neighboring countries. During the following decades and until the end of the twentieth century, the ratio of informal unions to legal marriages increased across all educational groups, but primarily among women with less than secondary schooling. This pattern changed with the turn of the century. From 2000 to 2011, the share of consensual unions remained unchanged for partnered women with less than primary education, whereas it increased from 20 to 32 % among women with completed secondary education and from 10 to 31 % among women with post-secondary education. These latter two educational groups currently comprise the majority of the female population aged 25–29.

As already mentioned, Guatemala is the only country in the region that has experienced a downward trend in cohabitation over the second half of the past century, although this trend has been reversed in the past decade. In fact, the recent increase in cohabitation observed from the mid-1990s to 2011 among young women is primarily concentrated in the higher educated groups, resulting in a much weaker educational gradient than in the past.

Despite the existing divergences across countries in the evolution of cohabitation, there is a phenomenon emerging in the more recent period that is shared by all countries: the increase in consensual unions among the higher educated strata. In this regard, Central America follows a similar pattern to the rest of Latin America, in spite of its slower pace of progress in educational expansion and socioeconomic development. In fact, in those countries that had already reached in the 1970s high levels of cohabitation – which was strongly clustered in the poor social groups–, most of the recent increase in cohabitation is concentrated in the higher educated strata.

Further research with longitudinal data is needed to examine the duration patterns of cohabitation and the rate of transition from cohabitation to marriage among well educated women in order to ascertain whether consensual unions are considered a temporary stage in the path to marriage and motherhood or an alternative to marriage, and hence a family arrangement where children are typically born and raised, as is the case among their lower educated counterparts.

A recent study has examined fertility trends and patterns for consensually and legally married women across different educational strata in 13 Latin American countries, including Costa Rica and Panama (Laplante et al. 2015). One of the relevant findings of this study was that similarities in reproductive behavior between marital and nonmarital unions are currently not confined to socially disadvantaged groups, but apply as well to the better-off. Three decades ago, entering cohabitation and having children within cohabitation was atypical among highly educated women. However, nowadays not only are university-educated women more likely to enter a consensual union, but their childbearing patterns do not differ much from those of their married counterparts. In the case of Costa Rica, fertility was much lower among highly educated women in consensual unions than in marriages in 1984, but it was only slightly lower in 2000. In the case of Panama, there were no significant differences in fertility among highly educated women in informal and formal unions already in 1980, and this pattern remains unaltered in 2010. Although we lack empirical evidence for the rest of the Central American countries, the patterns documented for Costa Rica and Panama seem to suggest that highly educated women are not entering consensual unions merely as a trial marriage, where childbearing is postponed until the relationship is formalized.

8 The Socio-demographic Profile of Cohabiting and Married Young Women

The socio-demographic profile of young cohabiting and married women can give us some hints as to the background factors associated with opting for a consensual union rather than a formal marriage in the process of family formation. A prior study which compared the socio-demographic characteristics of cohabiting and married women of reproductive age in Central America, based on data from the Demographic and Health Surveys for El Salvador (1985), Guatemala (1995) and Nicaragua (1998), documented that women in consensual unions were on average younger, less educated, had experienced the key transitions to adulthood (sexual initiation, first union and first birth) at an earlier age, and were more likely to have experienced a prior union disruption, a profile that suggests an earlier initiation and higher instability of consensual unions relative to marriages (Castro-Martín 2001). A more recent study adopting a life course approach and based on the Demographic and Health Surveys and Reproductive Health Surveys conducted during the 2000s in Honduras, Guatemala and Nicaragua also documented that an early onset of sexual activity increased the likelihood of entering cohabitation in Honduras and Nicaragua, and found strong indications that consensual unions were less stable than formal marriages (Grace and Sweeney 2014).

Since not all Central American countries have recent survey data, we will compare the socio-demographic characteristics of young cohabiting and married women based on the latest census data available. Although cross-sectional census data do not allow us to determine which background factors influence the patterns of entry into and exit from consensual and marital unions, the socio-demographic profile of currently partnered women can still shed light on the distinct features of each type of partnership.

Table 6.4 presents the socio-demographic composition of cohabiting and married women aged 25–29 in all Central American countries in recent times. As discussed before, although the educational gradient of cohabitation has changed significantly over time, it remains negative for all countries. The indicators in this table confirm that young women in consensual unions not only have lower education but also have less educated partners than their married counterparts. Nonetheless, consensual unions are no longer negligible among the middle and upper educated groups, as was the case in the past. The proportion of cohabiting young women who have completed secondary or tertiary education ranges from 16 % in Guatemala and El Salvador to 47 % in Panama. Women in consensual unions are also more likely to reside in rural areas than married women, although differentials are relatively small except for Panama. With regard to labor force participation, young women in consensual unions are slightly less likely to be employed than their married counterparts. Differentials are only relatively large in the case of Panama, where 36 % of young cohabiting women are currently working compared to 54 % of young married women.

The relative prevalence of consensual unions in the indigenous population is not uniform across societies. Cohabiting women are more likely to belong to an indigenous group than married women in Costa Rica, Nicaragua, and particularly in Panama, but the opposite pattern is observed in Guatemala and Honduras. In the case of Guatemala, which holds the largest indigenous population in the Isthmus, previous studies have documented a lower prevalence of unmarried cohabitation among Maya groups than the rest of the population (Castro-Martín 2001; Grace and Sweeney 2014). Although we do not know exactly since when this pattern holds, in the 1987 Guatemalan Demographic and Health Survey the proportion of consensual unions among partnered women aged 25–29 was already lower among indigenous women (32 %) than among the rest of women (41 %).

With regard to women’s reproductive patterns by union type, it is well-established that childbearing is not circumscribed to formal marriages in Latin America (Castro-Martín et al. 2011). The above-mentioned study by Laplante et al. (2015) documented that fertility levels have not differed significantly between consensual and married unions during the past four decades in 13 Latin American countries, including Costa Rica and Panama, and came to the conclusion that the legal status of conjugal unions has no relevance for Latin American women’s childbearing behavior. Studies focused on the Central America region have also shown that consensual unions constitute a usual and socially acceptable context to have and raise children (Castro-Martín 2001). According to the indicators in Table 6.4, the large majority of women aged 25–29 in both consensual and marital unions have borne at least one child. The incidence of childlessness is in fact lower among cohabiting women than married women in most countries, although differences are relatively small except in Costa Rica and Panama, where the proportion of cohabiting women aged 25–29 who has not made the transition to motherhood is about half that of married women. Observed differentials are probably partly linked to the lower use of contraception by low educated women and to the fact that cohabitation is a common strategy to cope with unplanned adolescent pregnancy among poor social strata (Rodríguez Vignoli 2004). Overall, these indicators confirm that childbearing remains commonplace within consensual partnerships in Central America and that it does not seem to trigger the legalization of the union. With regard to differentials in the number of children born, the descriptive results point towards higher fertility levels in consensual unions than marriages, but these differentials are largely explained by educational composition, which is closely linked to contraceptive use (Laplante et al. 2015).

The intergenerational support provided by the extended family system continues to play a key role in the Latin American context and it has been argued to explain the resilience of families during difficult economic periods and to alleviate the consequences of precarious situations (Fussell and Palloni 2004). Co-residence with parents, in-laws, other relatives or unrelated persons in extended and composite households is relatively common among young cohabiting and married women in Latin America (Esteve et al. 2012b), and it represents a frequent strategy to cope with housing shortage, to broaden the sources of income or to facilitate the access to employment for mothers of young children, particularly in lower social strata (Ullmann et al. 2014). Table 6.4 presents the proportion of cohabiting and married women aged 25–29 that co-reside with their own parent/s or parent/s-in-law. This proportion is probably underestimated because it is calculated based on women’s type of family relationship with the household head, and in multigenerational households, it might be the case that none of the co-resident parents or parents-in-law are classified as household heads. The proportion of women living in the parental household is also notably lower than when co-residence with other kin and non-relatives is also taken into account, as in the study by Esteve et al. (2012b). Despite these limitations, the overall patterns observed indicate higher levels of intergenerational co-residence in the poorer countries of the region, such as Nicaragua, than in better-off countries, such as Costa Rica. However, although we expected to find a higher incidence of co-residence with own parents or in-law parents among young cohabiting women than married women, given that the former typically face more precarious economic conditions, the data in Table 6.4 show relatively small differentials in living arrangements by partnership type.

9 Conclusions

Central America has a long history of family formation via consensual union instead of formal marriage. The historically high levels of cohabitation have persisted throughout the twentieth century up to the present day. In the 1960 census round, the earliest census round for which we had data access for all countries, consensual unions surpassed formal marriages among women of reproductive age in Guatemala and Panama, and comprised about 40–50 % of all unions in the rest of the countries except Costa Rica. At that time, Central American countries were predominantly rural societies, with very high levels of illiteracy and extreme poverty. Consensual unions were the norm among the lower social strata and functioned as a kind of surrogate marriage and an acceptable family arrangement for bearing and raising children. Pre-existing traditions and economic constraints rather than individual preferences probably lay behind the prevailing patterns of partnership formation at that moment. Since then, the Central American Isthmus has gone through important socioeconomic transformations, including economic growth, increasing urbanization and the expansion of mass education, although the persistence of high levels of poverty and pronounced social inequality indicates that the benefits of socioeconomic development have not yet reached large segments of the population. Against this background, changes in the patterns of union formation have been more modest than in other Latin American regions, but not inexistent.

The evolution in the prevalence of consensual unions over the past five decades described in this chapter shows a different pace of change across countries and an increasing convergence in cohabitation levels in the Isthmus. In general, countries which already had high levels of cohabitation in the 1960s have experienced small to moderate increases whereas countries with traditionally low levels of cohabitation, such as Costa Rica, have undergone large increases. Guatemala is the only country where a downward trend can be observed during the second half of the twentieth century, although recent survey data from 2011 suggest that the decline in cohabitation has halted and is possibly reversing.

By the end of the last century, the downward trend in Guatemala and the small or moderate increase in cohabitation in those countries where consensual unions had already surpassed formal marriages appeared to signal an upper ceiling to the expansion of cohabitation in Central America. However, more recent surveys and data from the 2010 census round indicate that the rise in cohabitation has not come to an end in the region. Since the turn of the twenty-first century, consensual unions have gained prominence in all countries but El Salvador, particularly if we focus on the 25–29 age group.

This recent increase has been largely concentrated among women with secondary and higher education, for whom cohabitation was negligible in the past. The historically negative educational gradient of cohabitation remains largely in place, but differentials in union patterns by educational level have narrowed considerably in the past two decades. Unmarried cohabitation remains the dominant type of conjugal union among the lesser educated women, but in recent times cohabitation has become an increasingly frequent partnership option among higher educated women as well. The recent spread of cohabitation among the middle and upper classes has probably been facilitated by the wide social recognition conferred on consensual unions in the lower strata, but it challenges the traditional strong association between cohabitation, poverty and social disadvantage. Consensual unions presumably have different social meanings, underlying motivations and implications for the family life cycle across social classes (Covre-Sussai et al. 2014). In order to highlight these divergences, a growing number of studies distinguish between “traditional” consensual unions, linked to pre-existing customs, economic constraints and women’s limited choices, and “modern” consensual unions, driven by increasing women’s empowerment among the better educated strata as well as changes in values regarding life styles and family behaviors (Quilodrán 2011; Esteve et al. 2012a; Covre-Sussai et al. 2015), along the lines of the Second Demographic Transition (Lesthaeghe 2010). Yet, economic uncertainty during early adulthood cannot be discarded as an additional factor driving the recent expansion of cohabitation among the middle classes at least in the first stages of family formation (García and Rojas 2004; Arriagada 2007). In order to compare the older and newer patterns of cohabitation, further research with longitudinal data is needed in order to ascertain whether the emerging form of cohabitation among the middle and upper classes is usually a transitional stage in the family formation process that precedes union formalization or a more long-term alternative to marriage, as it has traditionally been for the lower class. Recent studies highlighting the increasing convergence of childbearing patterns between cohabiting and married women in the upper social strata seem to suggest that highly educated women do not currently view cohabitation merely as a prelude to marriage (Laplante et al. 2015).

Research on gender dynamics in consensual unions across social strata could also shed some light on the different meanings attached to cohabitation by different social groups (Covre-Sussai et al. 2013). Gender relations are expected to be more egalitarian in the “modern” type of cohabitation than in the “traditional” type. However, a former study that examined conjugal violence by union type in four Latin American countries, including Nicaragua, found that women in consensual unions were more likely to be controlled by their partners and to have experienced conjugal violence than married women, and this finding applied to both low educated and highly educated women (Castro-Martín et al. 2008). Hence, more in-depth research is needed on gender attitudes and intra-couple balance of power by union type, as well as on the role of economic constraints versus preferences for interpersonal commitment over institutional regulation as motivations for entering a consensual union in order to disentangle the different rationales, social meanings, and repercussions of cohabitation across social strata. Furthermore, preferences and motivations to form a consensual union might differ not only by social class but also between men and women.

In sum, besides the long-standing coexistence of marriages and consensual unions in the region, the contemporary coexistence of traditional and modern types of cohabitation adds another layer of complexity to nuptiality patterns in Central America. This chapter has illustrated that, despite historically high levels of cohabitation in the region, the expansion of cohabitation has not come to an end so far, largely because of the recent increase in consensual unions among the higher educated strata. The trend analysis has revealed not only a tendency towards convergence in cohabitation levels across all countries in the Isthmus, but also towards diminishing gaps in partnership types across social strata. In most countries, cohabitation seems to have almost reached an upper ceiling among the lesser educated, but there is still ample room for further increase in the middle and upper education groups. The prospective expansion of secondary and tertiary education to larger segments of the population, continuing changes in attitudes and values regarding family and life styles, and advances in the legal and financial protection of children after the disruption of a consensual union are likely to condition further increases in cohabitation throughout the Central American region in the coming decades.

Notes

- 1.

The Gini coefficient measures the deviation of the distribution of income among individuals or households within a country from a perfectly equal distribution. A value of 0 represents absolute equality and a value of 100 absolute inequality.

- 2.

The net enrollment rate in primary education accounts for the proportion of children of enrollment age who are actually enrolled in primary education.

- 3.

Belize is not included in this chapter because of the paucity of statistical data and because, as a former British colony until 1981, it has a different historical and cultural heritage than the rest of the countries in the Isthmus. Also, Belize shares with the Caribbean region a relatively high incidence of visiting-partner relationships, suggesting the existence of more complex union patterns than in the rest of the Central American region. Nonetheless, we include the share of consensual unions among partnered women in Table 6.2 according to the Belize 2010 census to show that current levels of cohabitation are also high.

References

Arriagada, I. (2002). Changes and inequality in Latin American families. CEPAL Review, 77, 135–153.

Arriagada, I. (2007). Familias latinoamericanas: Cambiantes, diversas, desiguales. Papeles de Población, 53, 9–22.

Binstock, G., & Cabella, W. (2011). La nupcialidad en el Cono Sur: evolución reciente en la formación de uniones en Argentina, Chile y Uruguay. In G. Binstock & J. Melo (Eds.), Nupcialidad y familia en la América Latina actual (pp. 35–60). Rio de Janeiro: ALAP.

Bozon, M., Gayet, C., & Barrientos, J. (2009). A life-course approach to patterns and trends in modern Latin American sexual behavior. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 51(Supplement 1), S4–S12. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a2652.

Castro-Martín, T. (2001). Matrimonios sin papeles en Centroamérica: persistencia de un sistema dual de nupcialidad. In L. Rosero-Bixby (Ed.), Población del Istmo 2000: Familia, Migración, Violencia y Medio Ambiente (pp. 41–65). San José, Costa Rica: Centro Centroamericano de Población. http://ccp.ucr.ac.cr/libros/poblaist/pdf/poblacion_istmo.pdf

Castro-Martín, T. (2002). Consensual unions in Latin America: Persistence of a dual nuptiality system. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 33(1), 35–55.

Castro-Martín, T., & Juárez, F. (1995). The impact of women’s education on fertility in Latin America: Searching for explanations. International Family Planning Perspectives, 21(2), 52–57+80.

Castro-Martín, T., Martín-García, T., & Puga, D. (2008). Tipo de unión y violencia de género: Una comparación de matrimonios y uniones consensuales. In L. Rodríguez Wong (Ed.), Población y Salud Sexual y Reproductiva en América Latina (pp. 331–348). Río de Janeiro: ALAP. http://www.alapop.org/docs/publicaciones/investigaciones/SSR_parteIV-1.pdf

Castro-Martín, T., Cortina, C., Martín-García, T., & Pardo, I. (2011). Maternidad sin matrimonio en América Latina: Un análisis comparativo a partir de datos censales. Notas de Población, 93, 37–76.

CEPAL (Naciones Unidas, Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe). (2010). Achieving the Millennium Development Goals with Equality in Latin America and The Caribbean: Progress and Challenges. Santiago de Chile: CEPAL, United Nations publication, 395 pages. LC/G.2460.

CEPAL (Naciones Unidas, Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe). (2013). Gender equality observatory of Latin America and the Caribbean annual report 2012. Santiago de Chile: CEPAL, United Nations publication, 106 pages. LC/G.2561.

CEPAL (Naciones Unidas, Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe). (2014). Social panorama of Latin America 2014. Santiago de Chile: CEPAL, United Nations publication, 286 pages. ISBN: 978–9211218824.

CEPALSTAT. Databases and statistical publications. CEPAL (Naciones Unidas, Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe). http://estadisticas.cepal.org/cepalstat

Covre-Sussai, M., Meuleman, B., Botterman, S., & Matthijs, K. (2013). Measuring gender equality in family decision making in Latin America: A key towards understanding changing family configurations. Genus, 69(3), 47–73.

Covre-Sussai, M., Van Bavel, J., Matthijs, K., & Swicegood, G. (2014). Disentangling the different types of cohabitation in Latin America: Gender symmetry and contextual influences. Available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=2376739

Covre-Sussai, M., Meuleman, B., Botterman, S., & Matthijs, K. (2015). Traditional and modern cohabitation in Latin America: A comparative typology. Demographic Research, 32(32), 873–914.

De Vos, S. (2000). Nuptiality in Latin America. In S. L. Browning & R. R. Miller (Eds.), Till death do us part: A multicultural anthology on marriage (pp. 219–243). Stamford, CT: JAI Press.

Esteve, A., Garcia-Román, J., & McCaa, R. (2010). La enumeración de la soltería femenina en los censos de población: sesgo y propuesta de corrección. Papeles de Población, 16(66), 9–40.

Esteve, A., Lesthaeghe, R., & López-Gay, A. (2012a). The Latin American cohabitation boom, 1970–2007. Population and Development Review, 38(1), 55–81.

Esteve, A., Garcia-Román, J., & Lesthaeghe, R. (2012b). The family context of cohabitation and single motherhood in Latin America. Population and Development Review, 38(4), 707–727.

Fussell, E., & Palloni, A. (2004). Persistent marriage regimes in changing times. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 66(5), 1201–1213.

García, B., & de Oliveira, O. (2011). Family changes and public policies in Latin America. Annual Review of Sociology, 37, 593–611.

García, B., & Rojas, O. (2004). Las uniones conyugales en América Latina: Transformaciones en un marco de desigualdad social y de género. Notas de Población, 78, 65–96.

Grace, K. (2010). Contraceptive use and intent in Guatemala. Demographic Research, 23(12), 335–364.

Grace, K., & Sweeney, S. (2014). Pathways to marriage and cohabitation in Central America. Demographic Research, 30(6), 187–226.

Hallman, K., Peracca, S., Catino, J., & Ruiz, M. J. (2007). Indigenous girls in Guatemala: Poverty and location. In M. Lewis & M. Lockheed (Eds.), Exclusion, gender and schooling: Case studies from the developing world (pp. 145–175). Washington, DC: Center for Global Development. ISBN 1-933286-22-8.

Hammill, M. (2007). Growth, poverty and inequality in Central America. Mexico D. F.: United Nations, CEPAL Serie Estudios y Perspectivas No. 88, 74 pages. ISBN 9789211216592. http://repositorio.cepal.org/handle/11362/5025

Kuzneof, E., & Oppenheimer, R. (1985). The family and society in nineteenth century Latin America: An historiographical introduction. Journal of Family History, 10(3), 215–234.

Laplante, B., & Street, M. C. (2009). Los tipos de unión consensual en Argentina entre 1995 y 2003: una aproximación biográfica. Estudios Demográficos y Urbanos, 24(2), 351–387.

Laplante, B., Castro-Martín, T., Cortina, C., & Martín-García, T. (2015). Childbearing within marriage and consensual union in Latin America, 1980–2010. Population and Development Review, 41(1), 85–108.

Lavrin, A. (Ed). (1989). Sexuality and marriage in Colonial Latin America, Latin American studies series. Lincoln/London: University of Nebraska Press, 349 pages. ISBN 080327940X, 9780803279407.

Lesthaeghe, R. (1995). The second demographic transition in western countries. In K. Oppenheim-Mason & A.-M. Jensen (Eds.), Gender and family change in industrialized countries (pp. 17–62). Oxford: Clarendon.

Lesthaeghe, R. (2010). The unfolding story of the second demographic transition. Population and Development Review, 36(2), 211–252.

Lion, K., Prata, N., & Stewart, C. (2009). Adolescent childbearing in Nicaragua: A quantitative assessment of associated factors. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 35(2), 91–96.

López-Gay, A., Turu, A., Esteve, A., Kennedy, S., López-Colás, J., Laplante, B., Permanyer, I., & Lesthaeghe, R. (2014). Towards a geography of unmarried cohabitation in the Americas. Demographic Research, 30(59): 1621–1638.

McCaa, R. (1994). Marriage ways in Mexico and Spain, 1500–1900. Continuity and Change, 9(1), 11–43.

Milanich, N. (2002). Historical perspectives on illegitimacy and illegitimates in Latin America. In T. Hecht (Ed.), Minor omissions: Children in Latin American history and society (pp. 72–101). Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0-299-18030-1, 0-299-18034-4.

Minnesota Population Center. (2014). Integrated public use microdata series, International: Version 6.3 [Machine-readable database]. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota

Monteith, R. S., Stupp, P. W., & McCracken, S. D. (2005). Reproductive, maternal and child health in Central America: Trends and challenges facing women and children. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, University of Texas. 126 pages.

Parrado, E., & Tienda, M. (1997). Women’s roles and family formation in Venezuela: New forms of consensual unions? Social Biology, 44(1–2), 1–24.

Pebley, A., & Rosero-Bixby, L. (Eds). (1997). Demographic diversity and change in the Central American Isthmus. RAND Corporation, Conference Proceedings (Rand Corporation), Vol. 135. ISBN 0833025511, 9780833025517. http://www.rand.org/pubs/conf_proceedings/CF135.html

Pérez Brignoli, H. (1989). A brief history of Central America. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 240 pages. ISBN 0520909763, 9780520909762.

Programa Estado de la Nación. (2014). Estadísticas de Centroamérica. San José: Programa Estado de la Nación. http://www.estadonacion.or.cr/otras-publicaciones-pen/productos-intermedios-pen/estadisticas-de-centroamerica-2014

Quilodrán, J. (1999). L’union libre en Amérique Latine: aspects récents d’un phénomène séculaire. Cahiers Québécois de Démographie, 28(1–2), 53–80.

Quilodrán, J. (2011). Un modelo de nupcialidad post-transicional en América Latina?. In G. Binstock & J. Melo (Coord), Nupcialidad y Familia en la América Latina Actual. Rio de Janeiro: ALAP, Serie Investigaciones No. 11, pp. 11–33.

Remez, L., Singh, S., & Prada, E. (2009). Trends in adolescent unions and childbearing in four Central American countries. Población y Salud en Mesoamérica, 7(1): article 5. http://ccp.ucr.ac.cr/revista/

Rodríguez Vignoli, J. (2004). Cohabitación en América Latina: ¿modernidad, exclusión o diversidad? Papeles de Población, 10(40), 97–145.

Rodríguez Vignoli, J. (2011). La situación conyugal en los censos latinoamericanos de 2010: relevancia y perspectivas. In M. Ruiz Salguero & J. Rodríguez Vignoli (Eds.), Familia y Nupcialidad en los Censos Latinoamericanos Recientes: Una Realidad que Desborda los Datos (Vol. 99, pp. 47–70). Santiago de Chile: Naciones Unidas, Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe, CEPAL, Serie Población y Desarrollo. ISBN 9210545400, 9789210545402. http://www.eclac.org/publicaciones/xml/9/42709/lcl3293e-P.pdf

Samandari, G., & Speizer, I. S. (2010). Adolescent sexual behavior and reproductive outcomes in Central America: Trends over the past two decades. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 36(1), 26–35.

Socolow, S. M. (2000). The women of colonial Latin America. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1316194000, 9781316194003.

Stupp, P. W., Daniels, D., & Ruiz, A. (2007). Reproductive, maternal and child health in Central America: Health Equity Trends. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, University of Texas, 126 pages.

Ullmann, H., Maldonado, C., & Rico, M. N. (2014). Families in Latin America: Changes, poverty and access to social protection. International Journal of Sociology of the Family, 40(2), 123–152.

UNDP (United Nations Development Programme). (2014). Human development report 2014. Sustaining human progress: Reducing vulnerabilities and building resilience. New York: United Nations Development Programme. ISBN 978-92-1-126368-8.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, duplication, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the work’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if such material is not included in the work’s Creative Commons license and the respective action is not permitted by statutory regulation, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to duplicate, adapt or reproduce the material.

Copyright information

© 2016 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Castro-Martín, T., Domínguez-Rodríguez, A. (2016). Consensual Unions in Central America: Historical Continuities and New Emerging Patterns. In: Esteve , A., Lesthaeghe, R. (eds) Cohabitation and Marriage in the Americas: Geo-historical Legacies and New Trends. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31442-6_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31442-6_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-31440-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-31442-6

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)