Abstract

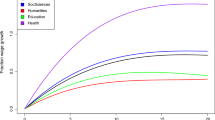

This chapter reviews the evidence on the labor market returns to investing in a college education for students in the U.S. First, we describe the primary method used to estimate the return on investment and catalog the main datasets used. We then summarize the available evidence on the returns to different awards and other types of investment. We show how earnings gains clearly vary with the incremental level and quality of postsecondary education. Completing a bachelor’s degree is associated with large gains in earnings amounting to at least one-quarter million dollars on average over the lifetime. Completing an associate degree is associated with sizeable and persistent earnings advantages over no college award. Completing a certificate can yield earnings gains, but these are variable and may only be temporary. Looking at field of study and college characteristics, we also find clear evidence of variability in returns. Finally, we consider the skills of college students need, both in their current occupations and in the future as robots and computers impact on what workers do. Overall, we find most college investments to have strong labor market pay-offs and that these pay-offs are unlikely to diminish in the near future.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

- 1.

Early analyses justified the use of Mincerian OLS estimation on the grounds that positive and negative biases offset each other (Griliches, 1977). Gelbach (2016) demonstrates how the specific influence of each additional covariate may be misinterpreted. Here we are interested in the most valid estimate of the returns to education, not the measured influence of each covariate.

- 2.

Other biases may be significant. For example, Webber (2016) identifies a sizeable influence of non-cognitive characteristics such as an individual’s locus of control and self-esteem. However, these characteristics may themselves be endogenous to either earnings (persons with high earnings may then report higher self-esteem) or education (those with degrees may report higher self-esteem; see de Araujo & Lagos, 2013).

- 3.

For example, in their detailed analysis, Carneiro et al. (2011, p. 2779) conclude that “[s]ome marginal expansions of schooling produce marginal gains that are well below average returns. For other policies associated with other marginal expansions, the marginal gains are substantial.”

- 4.

UI earnings data have low imputation, self-reporting, and nonresponse bias. However, UI data exclude independent contractors, military personnel, some federal personnel, and those working in the informal sector. Workers who migrate out of state are also excluded. Overall, UI coverage is reasonably high, with more than 90% of college enrollees having at least one wage record. For more information on the quality of these datasets, see Liu et al. (2015).

- 5.

Vuolo, Mortimer, and Staff (2016) estimated the returns to college using the longitudinal Youth Development Survey. Although a small sample, the survey includes measures of biweekly earnings from 2005 to 2011, and earnings gains can be calculated relative to non-completers at either a two-year or four-year college. These estimates are very close to the consensus values for associate degrees. Adjusted to 2014 dollars, the returns over non-completers for associate degree holders are $2250 per quarter. Using fixed effects specifications for female welfare recipients in Colorado, Turner (2016) finds near-equivalent results. Adjusting for the types of associate degrees, the estimated earnings gain from completing an associate degree is $1840.

- 6.

Using the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY79), Agan (2014) separates out decision nodes based on college sector choices to yield eight different pathways. However, this method does not allow for non-completers to be linked to particular groups of completers such that ex ante returns could be calculated for programs. In most studies, dropouts are identified ex post and, as a combined group, are separated from all completers.

- 7.

Alternatively, there may be a synergy effect: the combination and accumulation of credits within the award may represent a more valuable accumulation of skills than credits alone. For example, 60 random credits that do not correspond to an award are unlikely to be as valuable as 60 engineering credits that correspond to an associate degree in engineering.

- 8.

Overall, the Ashenfelter dip is $200 to $500 in each of the 2–4 quarters before enrollment. For Virginia, the estimated dip is $480 per quarter in the 2 years before college enrollment (Jaggars & Xu, 2016, Table 2); for North Carolina, it is $370 for men ($210 for women) in the four quarters prior to enrollment (Liu, Belfield, & Trimble, 2015, Table 6). Finally, for Colorado welfare recipients, Turner (2016) estimates a decline in quarterly earnings by $900–$1400 (from $1700–$2200 down to $800) over one year prior to entry (with most of the decline in the quarter prior to enrollment). For California and Michigan, Bahr et al. (2015) and Bahr (2016) report an unspecified but significant Ashenfelter dip.

- 9.

The differences in the results of these studies may be explained by empirical and methodological differences. The studies use different ways of identifying for-profit students. The studies also use different approaches to address the challenges of selection bias. Deming et al. (2012) use propensity score matching. Lang and Weinstein (2013) use a maximum likelihood sample selection model as well as propensity score matching. Chung (2012) directly addresses selection bias by estimating a multinomial logit of for-profit college choice, including variables for tuition prices, relative earnings, and distance to college. Cellini and Chaudhary (2012) use an individual fixed-effects estimation strategy.

- 10.

Liu et al. (2015) also find evidence that longer periods at a transfer college are associated with higher earnings. Male (female) dropouts from four-year colleges have lifetime earnings gains of $52,000 ($73,000) over high school graduates. Dropouts from two-year colleges have earnings gains of $77,000 ($38,000).

- 11.

As explained by Autor (2015): “Tasks that cannot be substituted by automation are complemented by it,” and “Productivity improvements in one set of tasks almost necessarily increase the economic value of the remaining tasks.” In other words, the worker and the robot are helping each other. As the robots become more sophisticated and the workers become more educated, firms adjust their task requirements in response to more skilled labor (Sasser Modestino, Shoag, & Balance, 2015). Importantly, skilled workers are now providing the social skills the machine cannot. So, Weinberger (2014) finds that demand for cognitive skills has only increased for persons with high endowments of social skills.

References

Abel, J. R., Dietz, R., & Su, Y. (2014). Are recent college graduates finding good jobs? Current Issues in Economics and Finance, 20(1). New York: Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Acemoglu, D., & Restrepo, P. (2017). Robots and jobs: Evidence from US labor markets (NBER Working Paper No. 23285). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Agan, A. Y. (2014). Disaggregating the returns to college (Working Paper). Princeton: Princeton University.

Altonji, J. G., Blom, E., & Meghir, C. (2012). Heterogeneity in human capital investments: High school curriculum, college major, and careers. Annual Review of Economics, 4(1), 185–223. https://doi.org/10.3386/w17985

Altonji, J. G., Elder, T. E., & Taber, C. R. (2005). Selection on observed and unobserved variables: Assessing the effectiveness of Catholic schools. Journal of Political Economy, 113(1), 151–184. https://doi.org/10.1086/426036

Altonji, J. G., Kahn, L. B., & Speer, J. D. (2014). Trends in earnings differentials across college majors and the changing task composition of jobs. American Economic Review, 104(5), 387–393. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.104.5.387

Altonji, J. G., & Zimmerman, S. D. (2017). The costs of and net returns to college major (NBER Working Paper No. 23029). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Andrews, R. J., Li, J., & Lovenheim, M. F. (2014). Heterogeneous paths through college: Detailed patterns and relationships with graduation and earnings. Economics of Education Review, 42, 93–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2014.07.002

Andrews, R. J., Li, J., & Lovenheim, M. F. (2016). Quantile treatment effects of college quality on earnings: Evidence from administrative data in Texas. Journal of Human Resources, 51(1), 200–238. https://doi.org/10.3386/w18068

Autor, D. H. (2015). Why are there still so many jobs? The history and future of workplace automation. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29(3), 3–30. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.29.3.3

Autor, D. H., & Handel, M. J. (2013). Putting tasks to the test: Human capital, job tasks, and wages. Journal of Labor Economics, 31(2), S59–S96. https://doi.org/10.3386/w15116

Avery, C., & Turner, S. (2012). Student loans: Do college students borrow too much—or not enough? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 26(1, Winter 2012), 165–192. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.26.1.165

Backes, B., Holzer, H. J., & Velez, E. D. (2015). Is it worth it? Postsecondary education and labor market outcomes for the disadvantaged. IZA Journal of Labor Policy, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40173-014-0027-0

Bahr, P. R. (2016). The earnings of community college graduates in California (CAPSEE Working Paper). New York: Center for Analysis of Postsecondary Education and Employment.

Bahr, P. R., Dynarski, S., Jacob, B., Kreisman, D., Sosa, A., & Wiederspan, M. (2015). Labor market returns to community college awards: Evidence from Michigan (CAPSEE Working Paper). New York: Center for Analysis of Postsecondary Education and Employment.

Bailey, T., & Belfield, C. R. (2012). Community college occupational degrees: Are they worth it? In L. Perna (Ed.), Preparing today’s students for tomorrow’s jobs in metropolitan America (pp. 121–148). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Bailey, T. R., Jaggars, S. S., & Jenkins, D. (2015). Redesigning America’s community colleges: A clearer path to student success. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Barrow, L., & Malamud, O. (2015). Is college a worthwhile investment? Annual Review of Economics, 7(1), 519–555. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics-080614-115510

Barrow, L., & Rouse, C. E. (2005). Do returns to schooling differ by race and ethnicity? American Economic Review, 95(2), 83–87. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.666824

Baum, S. (2016). Student debt: Rhetoric and reality (Working Paper). Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Beaudry, P., Green, D. A., & Sand, B. M. (2016). The great reversal in the demand for skill and cognitive tasks. Journal of Labor Economics, 34(S1, Part 2, January 2016), S199–S247. https://doi.org/10.3386/w18901.

Becker, G. S. (1964). Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis with special reference to education. New York: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Belfield, C. R. (2015). Weathering the Great Recession with human capital? Evidence on labor market returns to education from Arkansas (CAPSEE Working Paper). New York: Center for Analysis of Postsecondary Education and Employment.

Belfield, C. R. (2017). Estimating the returns to some college: Methodological issues (CAPSEE Working Paper). New York: Center for Analysis of Postsecondary Education and Employment.

Belfield, C. R., & Bailey, T. (2011). The benefits of attending community college: A review of the evidence. Community College Review, 39(1), 46–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091552110395575

Belfield, C. R., & Bailey, T. (2017). The labor market returns to sub-baccalaureate college: A review (CAPSEE Working Paper). New York: Center for Analysis of Postsecondary Education and Employment.

Bettinger, E., & Soliz, A. (2016). Returns to vocational credentials: Evidence from Ohio’s community and technical colleges (CAPSEE Working Paper). New York: Center for Analysis of Postsecondary Education and Employment.

Bound, J., Lovenheim, M., & Turner, S. (2010). Why have college completion rates declined? An analysis of changing student preparation and collegiate resources. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 2(3), 129–157. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.2.3.129

Byrne, D. M., Fernald, J. G., & Reinsdorf, M. B. (2016). Does the United States have a productivity slowdown or a measurement problem? Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 47(1, Spring 2016), 109–182. https://doi.org/10.1353/eca.2016.0014.

Cappelli, P. (2015). Will college pay off? A guide to the most important financial decision you’ll ever make. New York: Public Affairs.

Carneiro, P., Heckman, J. J., & Vytlacil, E. J. (2011). Estimating marginal returns to education. American Economic Review, 101(6), 2754–2781. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.101.6.2754

Carnevale, A. P., Hanson, A. R., & Gulish, A. (2013a). Failure to launch, structural shift and the new lost generation. Washington, DC: Georgetown University, Center on Education and the Workforce. Retrieved from https://cew.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/FTL_FullReport.pdf

Carnevale, A. P., Jayasundera, T., & Cheah, B. (2012a). The college advantage: Weathering the economic storm. Washington, DC: Georgetown University, Center on Education and the Workforce. Retrieved from http://cew.georgetown.edu/collegeadvantage/

Carnevale, A. P., Jayasundera, T., & Gulish, A. (2016). America’s divided recovery: College haves and have-nots. Washington, DC: Georgetown University, Center on Education and the Workforce. Retrieved from https://cew.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/Americas-Divided-Recovery-web.pdf

Carnevale, A. P., Rose, S. J., & Hanson, A. R. (2012b). Certificates: Gateway to gainful employment and college degrees. Washington, DC: Georgetown University, Center on Education and the Workforce. Retrieved from https://cew.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Certificates.FullReport.061812.pdf

Carnevale, A. P., Smith, N., & Strohl, J. (2013b). Recovery job growth and education requirements through 2020. Washington, DC: Georgetown University, Center on Education and the Workforce. Retrieved from https://cew.georgetown.edu/cew-reports/recovery-job-growth-and-education-requirements-through-2020/

Castex, G., & Dechter, E. K. (2014). The changing roles of education and ability in wage determination. Journal of Labor Economics, 32(4), 685–710. https://doi.org/10.1086/676018

Cellini, S., & Turner, N. (2018). Gainfully employed? Assessing the employment and earnings of for-profit college students using administrative data (NBER Working Paper No. 22287). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Cellini, S. R. (2010). Financial aid and for-profit colleges: Does aid encourage entry. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 29(3), 526–552. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.20508

Cellini, S. R. (2012). For-profit higher education: An assessment of costs and benefits. National Tax Journal, 65(1), 153–179. https://doi.org/10.17310/ntj.2012.1.06

Cellini, S. R., & Chaudhary, L. (2012). The labor market returns to a for-profit college education (NBER Working Paper No. 18343). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Chung, A. S. (2012). Choice of for-profit college. Economics of Education Review, 31(6), 1084–1101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2012.07.004

Cotner, H., Alamprese, J. A., & Limardo, C. (2017). The career pathways planner: A guide for adult education state leaders to promote local career pathways systems. New York: Abt Associates. Retrieved from http://abtassociates.com/AbtAssociates/files/db/db89c75e-a585-42f7-93f3-206b8bfeb906.pdf

Couch, K. A., & Placzek, D. W. (2010). Earnings losses of displaced workers revisited. American Economic Review, 100(1), 572–589. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.100.1.572

Dadgar, M., & Trimble, M. J. (2015). Labor market returns to sub-baccalaureate credentials: How much does a community college degree or certificate pay? Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 37(4), 399–418. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373714553814

Dale, S., & Krueger, A. B. (2014). Estimating the return to college selectivity over the career using administrative earnings data. Journal of Human Resources, 49(2), 323–358. https://doi.org/10.3386/w17159

Davis, S. J., Faberman, R. J., & Haltiwanger, J. C. (2012). Recruiting intensity during and after the Great Recession: National and industry evidence. American Economic Review, 102(3), 584–588. https://doi.org/10.3386/w17782

de Araujo, P., & Lagos, S. (2013). Self-esteem, education, and wages revisited. Journal of Economic Psychology, 34, 120–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2012.12.001

Deming, D. J., Goldin, C., & Katz, L. F. (2012). The for-profit postsecondary school sector: Nimble critters or agile predators. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 26(1), 139–164. https://doi.org/10.3386/w17710

Deming, D. J., & Kahn, L. (2017). Firm heterogeneity in skill demands (NBER Working Paper No. 23328). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Eide, E. R., Hilmer, M. J., & Showalter, M. H. (2016). Is it where you go or what you study? The relative influence of college selectivity and college major on earnings. Contemporary Economic Policy, 34(1), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/coep.12115

Elsby, M. W. L., Shin, D., & Solon, G. (2016). Wage adjustment in the Great Recession and other downturns: Evidence from the United States and Great Britain. Journal of Labor Economics, 34(S1, Part 2, January 2016), S249–S291. https://doi.org/10.1086/682407

Executive Office of the President. (2016). Artificial intelligence, automation, and the economy [Monograph]. Retrieved from https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/images/EMBARGOED%20AI%20Economy%20Report.pdf

Gelbach, J. (2016). When do covariates matter? And which ones, and how much. Journal of Labor Economics, 34(2), 509–543. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1425737

Gittleman, M., Monaco, K., & Nestoriak, N. (2016). The requirements of jobs: Evidence from a nationally representative survey (NBER Working Paper No. 22218). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Goldin, C., & Katz, L. F. (2008). The race between education and technology. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University.

Goldrick-Rab, S. (2016). Paying the price: College costs, financial aid, and the betrayal of the American dream. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Gordon, R. (2015). The rise and fall of American growth. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Gordon, R. J. (2016). The rise and fall of American growth. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Griliches, Z. (1977). Estimating the returns to schooling: Some econometric problems. Econometrica, 45(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.2307/1913285

Guvenen, F., Kaplan, G., Song, J., & Weidner, J. (2017). Lifetime incomes in the United States over six decades (NBER Working Paper No. 23371). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Hamermesh, D. S., & Donald, S. G. (2008). The effect of college curriculum on earnings: An affinity identifier for non-ignorable non-response bias. Journal of Econometrics, 144(2), 479–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2008.04.007

Handel, M. J. (2016). What do people do at work? Journal of Labour Market Research, 49(2), 177–197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12651-016-0213-1

Henderson, D. J., Polachek, S. W., & Wang, L. (2011). Heterogeneity in schooling rates of return. Economics of Education Review, 30(6), 1202–1214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2011.05.002

Hershbein, B., & Kearney, M. S. (2014). Major decisions: What graduates earn over their lifetimes (The Hamilton Project Report). Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution, The Hamilton Project. Retrieved from http://www.hamiltonproject.org/papers/major_decisions_what_graduates_earn_over_their_lifetimes/

Hodara, M., & Xu, D. (2014). Does developmental education improve labor market outcomes? Evidence from two states (CAPSEE Working Paper). New York: Center for Analysis of Postsecondary Education and Employment.

Hossler, D., Shapiro, D., Dundar, A., Chen, J., Zerquera, D., Ziskin, M., & Torres, V. (2012). Reverse transfer: A national view of student mobility from four-year to two-year institutions (Signature Report 3). Herndon: National Student Clearinghouse Research Center.

Jacobson, L., LaLonde, R., & Sullivan, D. G. (2005). Estimating the returns to community college schooling for displaced workers. Journal of Econometrics, 125(1–2), 271–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2004.04.010

Jaggars, S. S., & Xu, D. (2016). Examining the earnings trajectories of community college students using a piecewise growth curve modeling approach. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 9(3), 445–471. https://doi.org/10.1080/19345747.2015.1116033

Jepsen, C., Troske, K., & Coomes, P. (2014). The labor market returns to community college degrees, diplomas, and certificates. Journal of Labor Economics, 32(1), 95–121. https://doi.org/10.1086/671809

Kim, C., Tamborini, C. R., & Sakamoto, A. (2015). Field of study in college and lifetime earnings in the United States. Sociology of Education, 88(4), 320–339. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040715602132

Lang, K., & Weinstein, R. (2013). The wage effects of not-for-profit and for-profit certifications: Better data, somewhat different results. Labour Economics, 24, 230–243. https://doi.org/10.3386/w19135

Larrimore, J., Burkhauser, R. V., & Armour, P. (2013). Accounting for income changes over the Great Recession (2007–2010) relative to previous recessions: The importance of taxes and transfers (NBER Working Paper No. 19699). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Liu, V. Y. T., Belfield, C. R., & Trimble, M. J. (2015). The medium-term labor market returns to community college awards: Evidence from North Carolina. Economics of Education Review, 44, 42–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2014.10.009

Ma, J., Baum, S., Pender, M., & Welch, M. (2016). Trends in college pricing 2016. New York: College Board. Retrieved from https://trends.collegeboard.org/sites/default/files/2016-trends-college-pricing-web_1.pdf

Marcotte, D. E. (2010). The earnings effect of education at community colleges. Contemporary Economic Policy, 28(1), 36–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-7287.2009.00173.x

Martorell, P., & McFarlin, I. (2011). Help or hindrance? The effects of college remediation on academic and labor market outcomes. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 93(2), 436–454. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00098

Melguizo, T., & Wolniak, G. C. (2012). The earnings benefits of majoring in STEM fields among high achieving minority students. Research in Higher Education, 53(4), 383–405. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-011-9238-z

Minaya, V., & Scott-Clayton, J. (2017). Labor market trajectories for community college graduates: New evidence spanning the Great Recession (CAPSEE Working Paper). New York: Center for Analysis of Postsecondary Education and Employment.

Mincer, J. A. (1974). Schooling, experience, and earnings. New York: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Mitchell, J. (2014). Educational attainment and earnings inequality among US-born men. InMonograph. Washington DC: Urban Institute.

Olitsky, N. H. (2012). How do academic achievement and gender affect the earnings of STEM majors? A propensity score matching approach. Research in Higher Education, 55(3), 245–271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-013-9310-y

Oreopoulos, P., & Petronijevic, U. (2013). Making college worth it: A review of the returns to higher education. The Future of Children, 23(1), 41–65. https://doi.org/10.3386/w19053

Osterman, P., & Weaver, A. (2016). Community colleges and employers: How can we understand their connection? Industrial Relations, 55(4), 523–545. https://doi.org/10.1111/irel.12150

Reynolds, C. L. (2012). Where to attend? Estimating the effects of beginning college at a two-year institution. Economics of Education Review, 31(2), 345–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2011.12.001

Rouse, C. (2007). The earnings benefits from education. In C. R. Belfield & H. M. Levin (Eds.), The price we pay: The social and economic costs to the nation of inadequate education. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Sasser Modestino, A., Shoag, D., & Ballance, J. (2015). Upskilling: Do employers demand greater skill when skilled workers are plentiful? (Working Paper). Boston: Federal Reserve Bank of Boston.

Scott-Clayton, J., Crosta, P. M., & Belfield, C. R. (2014). Improving the targeting of treatment: Evidence from college remediation. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 36(3), 371–393. https://doi.org/10.3386/w18457

Scott-Clayton, J., & Wen, Q. (2017). Estimating returns to college attainment: Comparing survey and state administrative data based estimates (CAPSEE Working Paper). New York: Center for Analysis of Postsecondary Education and Employment.

Sprague, S. (2017). Below trend: The U.S. productivity slowdown since the Great Recession (Beyond the Numbers). Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/opub/btn/volume-6/below-trend-the-us-productivity-slowdown-since-the-great-recession.htm

Stevens, A., Kurlaender, M., & Grosz, M. (2015). Career-technical education and labor market outcomes: Evidence from California community colleges (CAPSEE Working Paper). New York: Center for Analysis of Postsecondary Education and Employment.

Syverson, C. (2017). Challenges to mismeasurement explanations for the US productivity slowdown. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(2), 165–186. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.2.165

Tamborini, C. R., Kim, C., & Sakamoto, A. (2015). Education and lifetime earnings in the United States. Demography, 52(4), 1382–1407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-015-0407-0

Thomas, S. L., & Zhang, L. (2005). Post-baccalaureate wage growth within 4 years of graduation: The effects of college quality and college major. Research in Higher Education, 46(4), 437–459. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-005-2969-y

Turner, L. J. (2016). The returns to higher education for marginal students: Evidence from Colorado welfare recipients. Economics of Education Review, 51, 169–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2015.09.005

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2012). The recession of 2007–2009 (BLS Spotlight). Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/spotlight/2012/recession/pdf/recession_bls_spotlight.pdf

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2018). Labor force participation rate: Some college or associate degree, 25 years and over. Retrieved from https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/LNS11327689

Valletta, R. G. (2016). Recent flattening in the higher education wage premium: Polarization, skill downgrading, or both? (NBER Working Paper No. 22935). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Vuolo, M., Mortimer, J. T., & Staff, J. (2016). The value of educational degrees in turbulent economic times: Evidence from the Youth Development Study. Social Science Research, 57, 233–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2015.12.014

Webber, D. A. (2014). The lifetime earnings premia of different majors: Correcting for selection based on cognitive, noncognitive, and unobserved factors. Labour Economics, 28, 14–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2014.03.009

Webber, D. A. (2016). Are college costs worth it? How ability, major, and debt affect the returns to schooling. Economics of Education Review, 53, 296–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2016.04.007

Weinberger, C. J. (2014). The increasing complementarity between cognitive and social skills. Review of Economics and Statistics, 96(5), 849–861. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00449

Xu, D., Jaggars, S. S., & Fletcher, J. (2016). How and why does two-year college entry influence baccalaureate aspirants’ academic and labor market outcomes? (CAPSEE Working Paper). New York: Center for Analysis of Postsecondary Education and Employment.

Xu, D., & Trimble, M. J. (2016). What about certificates? Evidence on the labor market returns to nondegree community college awards in two states. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 38(2). https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373715617827

Yagan, D. (2016). Is the Great Recession really over? Longitudinal evidence of enduring employment impacts (Working Paper). Berkeley: University of California, Berkeley and National Bureau of Economic Research.

Zeidenberg, M., Scott, M., & Belfield, C. (2015). What about the non-completers? The labor market returns to progress in community college. Economics of Education Review, 49, 142–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2015.09.004

Zimmerman, S. D. (2014). The returns to college admission for academically marginal students. Journal of Labor Economics, 32(4), 711–754. https://doi.org/10.1086/676661

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Belfield, C.R., Bailey, T.R. (2019). The Labor Market Value of Higher Education: Now and in the Future. In: Paulsen, M.B., Perna, L.W. (eds) Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research. Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research, vol 34. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03457-3_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03457-3_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-03456-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-03457-3

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)