Abstract

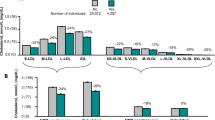

Some population groups in the United States have excess burdens of major risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and are more likely to have more risk factors than their white counterparts. Although the reasons for the excess CVD mortality among African-Americans remain controversial, it is evident that the high prevalence and suboptimal control of coronary risk factors and a greater degree of clustering of certain coronary risk factors contribute importantly. The predictive value of most conventional CVD risk factors appears to be similar for African-Americans and whites. Most population-based studies report that African-Americans have lower total serum cholesterol levels and a lower prevalence of hypercholesterolemia, but low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels were similar. Although African-Americans achieve a similar lowering of LDL-C with statin therapy, they are less likely to have increased cholesterol treated. Although low HDL as a CHD risk factor has been known for decades, only recently has clinical trial evidence addressed the benefits of raising high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-C.

On an average, higher levels of HDL-C are observed in African-American adults compared to white adults. Low hepatic lipase activity leads to increased plasma HDL-C concentrations in African-American men. Triglyceride levels in African-American men and women are generally lower than in white men and women, either with or without CHD. When African-Americans have elevated lipoprotein(a) levels in conjunction with small apolipoprotein(a) isoforms, a significant association with CHD has been found. Hispanics have lower mortality rates than non-Hispanic whites and blacks, referred to as the “Hispanic Paradox,” although a recent study provided evidence against the Hispanic Paradox in a population of diabetic individuals. Like African-Americans and other ethnic minorities, Hispanics have been under-represented in lipid clinical trials. South Asian Indians have a two- to three-fold higher prevalence of diabetes and a higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome than in whites. Premature atherosclerosis in young Asian Indians also appears to be related in part to the commonly observed dyslipidemia tetrad of elevated triglycerides, low HDL, small dense LDL-C, and elevated lipoprotein(a). High prevalence of modifiable risk factors provides great opportunity for prevention, risk reduction, reducing and ultimately eliminating disparities in cardiovascular care and outcomes.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

References

American Heart Association. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2005 Update. Dallas, TX: American Heart Association; 2005.

Clark LT, Ferdinand KC, Flack JM, et al. Coronary heart disease in African Americans. Heart Dis 2001; 3:97–108.

The Expert Panel. Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III): final report. Circulation 2002; 106:3146–3421.

Hutchinson RG, Watson RL, Davis CE, et al. Racial differences in risk factors for atherosclerosis: The ARIC Study. Angiology 1997; 48:279–290.

Hall WD, Clark LT, Wenger NK, et al. The metabolic syndrome in African Americans: a review. Ethn Dis 2003; 13:414–428.

Cooper RS, Liao Y, Rotimi C. Is hypertension more severe among U.S. blacks, or is severe hypertension more common? Ann Epidemiol 1996; 6:173–180.

Liao Y, Cooper RS, McGee DL, Mensah GA, Ghali JK. The relative effects of left ventricular hypertrophy, coronary artery disease, and ventricular dysfunction on survival among black adults. JAMA 1995; 273:1592–1597.

Gavin JR III. Diabetes in minorities: reflections on the medical dilemma and the healthcare crisis. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc 1995; 107:213–223.

Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study Group. Randomized trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Lancet 1994; 334:1383–1389.

Sacks FM, Pfeffer MA, Moye LA, et al. The effect of pravastatin on coronary events after myocardial infarction in patients with average cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med 1996; 335:1001–1009.

Long-term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischaemic Disease (LIPID) Study Group. Prevention of cardiovascular events and death with pravastatin in patients with coronary heart disease and a broad range of initial cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med 1998; 339:1349–1357.

Shepherd J, Cobbe SM, Ford I, et al., for the West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study Group. Prevention of coronary heart disease with pravastatin in men with hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med 1995; 333:1301–1307.

Downs JR, Clearfield M, Weis S, et al. Primary prevention of acute coronary events with lovastatin in men and women with average cholesterol levels: results of AFCAPS/TexCAPS. Air Force/Texas Coronary Atherosclerosis Prevention Study. JAMA 1998; 279:1615–1622.

Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20,536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2002; 360:7–22.

Cannon CP, Steinberg BA, Murphy SA, Mega JL, Braunwald E. Meta-analysis of cardiovascular outcomes trials comparing intensive versus moderate statin therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006; 48(3):438–445.

Gidding SS, Liu K, Bild DE, et al. Prevalence and identification of abnormal lipoprotein levels in a biracial population aged 23 to 35 years (the CARDIA study). The Coronary Risk Development in Young Adults study. Am J Cardiol 1996; 78: 304–308.

Watkins LO, Neaton JD, Kuller LH. Racial differences in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and coronary heart disease incidence in the usual care group of the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Am J Cardiol 1986; 57:538–545.

Hutchinson RG, Watson RL, Davis CE, et al. Racial differences in risk factors for atherosclerosis. The ARIC study. Angiology 1997; 48:279–290.

Keil JE, Sutherland SE, Hames CG, et al. Coronary disease mortality and risk factors in black and white men. Results from the combined Charleston, SC, and Evans County, Georgia, heart studies. Arch Intern Med 1995; 155:1521–1527.

Jain T, Peshock R, McGuire DK, et al.; the Dallas Heart Study Investigators. African Americans and Caucasians have a similar prevalence of coronary calcium in the Dallas Heart Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004; 44:1011–1017

Clark LT. Issues in minority health: atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease in African Americans. Med Clin N Am 2005; 89(5):977–1001.

Clark LT, Maki KC, Galant R, Maron DJ, Pearson TA, Davidson MH. Racial/ethnic differences in achievement of cholesterol treatment goals: results from the National Cholesterol Education Program Evaluation Project Utilizing Novel E-Technology (NEPTUNE) II. J Gen Intern Med 2006; 21(4):320–326.

LaRosa JC, Applegate W, Crouse JR III, et al. Cholesterol lowering in the elderly. Results of the Cholesterol Reduction in Seniors Program (CRISP) pilot study. Arch Intern Med 1994; 154:529–539.

Prisant LM, Downton M, Watkins LO, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of lovastatin in 459 African-Americans with hypercholesterolemia. Am J Cardiol 1996; 78:420–424.

Jacobson TA, Chin MM, Curry CL, et al. Efficacy and safety of pravastatin in African Americans with primary hypercholesterolemia. Arch Intern Med 1995; 155:1900–1906.

Ferdinand KC, Clark LT, Watson KE, et al.; the ARIES Study Group. Comparison of efficacy and safety of rosuvastatin versus atorvastatin in African-American patients in a six-week trial. Am J Cardiol 2006; 97:229–235.

Pearson TA, Laurora I, Chu H, Kafonek S. The lipid treatment assessment project (L-TAP): a multicenter survey to evaluate the percentages of dyslipidemic patients receiving lipid-lowering therapy and achieving low density lipoprotein cholesterol goals. Arch Intern Med 2000; 28:459–467.

Williams ML, Morris MT, Ahmad U, Yousseff M, Li W, Ertel N. Racial differences in compliance with NCEP II recommendations for secondary prevention at a veterans affairs medical center. Racial/Ethn Dis 2002;12: S1-58–62.

ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators of the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Major outcomes in moderately hypercholesterolemic, hypertensive patients randomized to Pravastatin versus usual care. The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT-LLT). JAMA 2002; 288:2988–3007.

Robins SJ, Collins D, Wittes JT, et al.; VA-HIT Study Group. Veterans Affairs High-Density Lipoprotein Intervention Trial. Relation of gemfibrozil treatment and lipid levels with major coronary events: VA-HIT: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001; 285:1585–1591.

Coronary Drug Project Research Group. Clofibrate and niacin in coronary heart disease. JAMA 1975; 231:360–381.

Canner PL, Berge KG, Wenger NK, Stamler J, Friedman L, Prineas RJ, Friedewald W. Fifteen year mortality in Coronary Drug Project patients: long-term benefit with niacin. J Am Coll Cardiol 1986; 8:1245–1255.

Nissen SE, Tsunoda T, Tuzcu EM, et al. Effect of recombinant ApoA-I Milano on coronary atherosclerosis in patients with acute coronary syndromes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003; 290:2292–2300.

Barter PJ, Caulfield M, Eriksson M, et al. Effects of torcetrapib in patients at high risk for coronary events. N Engl J Med 2007; 357:2109–2122.

Vega GL, Clark LT, Tang A, Marcovina S, Grundy SM, Cohen JC. Hepatic lipase activity is lower in African American men than in white American men: effects of 5' flanking polymorphism in the hepatic lipase gene (LIPC). J Lipid Res 1998; 39:228–232.

ustin MA, Hokanson JE, Edwards KL. Hypertriglyceridemia as a cardiovascular risk factor. Am J Cardiol 1998; 81(4A):7B–12B.

Rowland ML, Fulwood R. Coronary heart disease risk factor trends in blacks between the First and Second National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, United States, 1971–1980. Am Heart J 1984; 108:771–779.

Hutchinson RG, Watson RL, Davis CE, et al. Racial differences in risk factors for atherosclerosis. The ARIC study. Angiology 1997; 48:279–290.

Hall WD, Clark LT, Wenger NK, et al. The metabolic syndrome in African Americans: a review. Ethn Dis 2003; 13:414–428.

Ford ES, Giles WH, Dietz WH: Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US adults: findings from the Third National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey. J Am Med Assoc 2002; 287:356–359.

Watson KE, Topol EJ. Pathobiology of atherosclerosis: are there racial and racial/ethnic differences? Rev Cardiovasc Med 2004; 5(Suppl 3):S14–S21.

Moliterno DJ, Jokinen EV, Miserez AR, et al. No association between plasma lipoprotein(a) concentrations and the presence or absence of coronary atherosclerosis in African-Americans. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1995; 15:850–855.

Guyton JR, Dahlen GH, Patsch W, et al. Relationship of plasma lipoprotein Lp(a) levels to race and to apolipoprotein B. Arteriosclerosis 1985; 5:265–272.

Sorrentino MJ, Vielhauer C, Eisenbart JD, et al. Plasma lipoprotein(a) protein concentration and coronary artery disease in black patients compared with white patients. Am J Med 1992; 93:658–662.

Schreiner PJ, Heiss G, Tyroler HA, et al. Race and gender differences in the association of Lp(a) with carotid artery wall thickness. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1996; 16:471–478.

Stein JH, Rosenson RS. Lipoprotein Lp(a) excess and coronary heart disease. Arch Intern Med 1997; 157:1170–1176.

Kostner GM, Avogaro P, Cazzolato G, et al. Lipoprotein Lp(a) and the risk for myocardial infarction. Atherosclerosis 1981; 38:51–61.

Moliterno DJ, Lange RA, Meidell RS, et al. Relation of plasma lipoprotein(a) to infarct artery patency in survivors of myocardial infarction. Circulation 1993; 88:935–940.

Paultre F, Pearson TA, Weil HF, et al. High levels of Lp(a) with a small apo(a) isoform are associated with coronary artery disease in African American and white men. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2000; 20:2619–2624.

Rowland ML, Fulwood R. Coronary heart disease risk factor trends in blacks between the First and Second National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, United States, 1971–1980. Am Heart J 1984; 108:771–779.

Cutter GR, Burke GL, Dyer AR, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors in young adults. The CARDIA baseline monograph. Control Clin Trials 1991;12: 1S–25S, 51S–77S.

Hutchinson RG, Watson RL, Davis CE, et al. Racial differences in risk factors for atherosclerosis. The ARIC study. Angiology 1997; 48:279–290.

Grundy SM. Obesity, metabolic syndrome, and coronary atherosclerosis. Circulation 2002; 105:2696–2698.

Taylor H. Metabolic syndrome in African Americans, elderly. Jackson Heart Study and Metabolic Syndrome. AHA Scientific Sessions; 2005.

Wong ND, Pio JR, Franklin SS, L’Italien GJ, Kamath TV, Williams GR. Preventing coronary events by optimal control of blood pressure and lipids in patients with the metabolic syndrome. Am J Cardiol 2003; 91:1421–1426.

Schneck DW, Knopp RH, Ballantyne CM, McPherson R, Chitra RR, Simonson SG. Comparative effects of rosuvastatin and atorvastatin across their dose ranges in patients with hypercholesterolemia and without active arterial disease. Am J Cardiol 2003; 91:33–41.

Jones PH, Davidson MH, Stein EA, et al; the STELLAR Study Group. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of rosuvastatin versus atorvastatin, simvastatin, and pravastatin across doses (STELLAR trial). Am J Cardiol 2003; 92:152–160.

The Hispanic Population in the United States: March 2000. U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division, Racial/ethnic & Hispanic Statistics Branch. Available at: http://www.census.gov/population/www/socdemo/hispanic/ho00.html

Hunt KJ, Williams K, Resendez RG, et al. All-cause and cardiovascular mortality among diabetic participants in the San Antonio Heart Study: evidence against the Hispanic Paradox. Diabet Care 2002; 25(9):1557–1563.

Markides KS, Coreil J. The health of Hispanics in the southwestern United States: an epidemiologic paradox. Public Health Rep 1986; 101:253–265.

Liao Y, Cooper RS, Cao G, et al. Mortality from coronary heart disease and cardiovascular disease among adult U.S. Hispanics: findings from the National Health Interview Survey (1986 to 1994). J Am Coll Cardiol 1997; 30:1200–1205.

Lloret R, Ycas J, Stein M, Haffner S for the STARSHIP Study Group. Comparison of rosuvastatin versus atorvastatin in Hispanic-Americans with hypercholesterolemia (from the STARSHIP Trial). Am J Cardiol 2006; 98:768–773.

The Asian Population: 2000 (Census 2000 Brief). Issued February 2002. Available at: http://www.census.gov/prod/2002pubs/c2kbr01-16.pdf.

Enas EA. Clinical implications: dyslipidemia in the Asian Indian population. Monograph was adapted from material presented at the 20th Annual Convention of the American Association of Physicians of Indian Origin, Chicago, IL, 2002. Available at: http://www.cadiresearch.com/downloads/AAPImonograph.pdf

Singh V, Prakash D. Dyslipidemia in special populations: Asian Indians, African Americans, and Hispanics. Curr Atheroscler Rep 2006; 8:32–40.

Vikram NK, Pandey RM, Misra A, et al. Non-obese (body mass index <25 kg/m2) Asian Indians with normal waist circumference have high cardiovascular risk. Nutrition 2003; 19(6):503–509.

Deedwania PC, Gupta R. Prevention of coronary heart disease in Asian populations. In: Wong ND, ed. Preventive cardiology. New York, New York: McGraw-Hill, 2000: 503–516.

Gupta M, Singh N, Verma S. South Asians and cardiovascular risk: what clinicians should know. Circulation 2006; 113:e924–e929.

Enas EA, Garg A, Davidson MA, et al. Coronary heart disease and its risk factors in first-generation immigrant Asian Indians to the United States of America (CADI Study). Indian Heart J 1996; 48:343–353.

Kulkarni KR, Markovitz JH, Nanda NC, Segrest JP. Increased prevalence of smaller and denser LDL particles in Asian Indians. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1999; 19:2749–2755.

Deedwania CP, Gupta M, Stein M, Joseph Y, Gold A; IRIS Study Group. Comparison of rosuvastatin versus atorvastatin in South-Asian patients at risk of coronary heart disease (from the IRIS Trial). Am J Cardiol 2007; 99:1538–1543.

Resnick HE, Jones K, Ruotolo G, et al., for the Strong Heart Study. Insulin resistance, the metabolic syndrome, and risk of incident cardiovascular disease in non-diabetic American Indians: the Strong Heart Study. Diabet Care 2003; 26:861–867.

Lee ET, Howard BV, Savage PJ, et al. Diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in three American Indian populations aged 45–74 years: the Strong Heart Study. Diabet Care 1995; 18:599–610.

Howard BV, Lee ET, Cowan LD, et al. Rising tide of cardiovascular disease in American Indians: the Strong Heart Study. Circulation 1999; 99:2389–2395.

Goldberg RJ, Burchfiel CM, Benfante R, Chiu D, Reed DM, Yano K. Lifestyle and biologic factors associated with atherosclerotic disease in middle-aged men: 20-year findings from the Honolulu Heart Program. Arch Intern Med 1995; 155:686–694.

Abbott RD, Sharp DS, Burchfiel CM, et al. Cross-sectional and longitudinal changes in total and high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol levels over a 20-year period in elderly men: the Honolulu Heart Program. Ann Epidemiol 1997;7:417–424.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2009 Humana Press, a part of Springer Science+Business Media, LLC

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Clark, L.T., Shaheen, S. (2009). Dyslipidemia in Racial/Ethnic Groups. In: Ferdinand, K.C., Armani, A. (eds) Cardiovascular Disease in Racial and Ethnic Minorities. Contemporary Cardiology. Humana Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-59745-410-0_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-59745-410-0_7

Publisher Name: Humana Press

Print ISBN: 978-1-58829-981-9

Online ISBN: 978-1-59745-410-0

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)