Abstract

We collected norms on the gender stereotypicality of an extensive list of role nouns in Czech, English, French, German, Italian, Norwegian, and Slovak, to be used as a basis for the selection of stimulus materials in future studies. We present a Web-based tool (available at https://www.unifr.ch/lcg/) that we developed to collect these norms and that we expect to be useful for other researchers, as well. In essence, we provide (a) gender stereotypicality norms across a number of languages and (b) a tool to facilitate cross-language as well as cross-cultural comparisons when researchers are interested in the investigation of the impact of stereotypicality on the processing of role nouns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Thoughts and conceptual categorizations, as well as their relation to language, have long been studied and debated in cognitive psychology (e.g., Phillips & Boroditsky, 2003; Slobin, 1996). Within this domain, the mental representation of gender has been of particular interest, since research has revealed its reliance on both properties of the language, such as grammatical gender, and perceivers’ concepts, such as stereotypes (e.g., Carreiras, Garnham, Oakhill, & Cain, 1996; Gygax, Gabriel, Sarrasin, Oakhill, & Garnham, 2008; Stahlberg, Braun, Irmen, & Sczesny, 2007). Research that aims at disentangling the impacts of these sources can greatly profit from cross-linguistic and/or cross-cultural comparisons. To facilitate such research, in the present study we had two objectives:

First, we provide norms on the gender stereotypicality (or conceptual gender) of an extensive number of role nouns in seven European languages. These norms will enable researchers to take gender associations into account when selecting stimulus materials, especially for cross-linguistic or cross-cultural studies. Second, we present a Web-based tool that we developed for the collection of these norms in different languages. This tool takes into account cross-linguistic variations in with the way that the gender of nouns with human referents is grammatically encoded, so that equivalent procedures can be used with each language. More specifically, a questionnaire design was created that can be used despite such variations. As we outline below, the existence of grammatical gender in some languages, but not others, had implications for the questionnaire format used in this study. As a side effect, the tool can easily be extended for use with further languages. We believe that this tool will, therefore, be a valuable resource for researchers in various psychological disciplines who wish to systematically collect norms for different languages and/or from specific populations, for future studies.

Grammatical gender refers to a type of noun classification. In relation to this classification, most European languages can be assigned to one of the following four categories (Braun, Oakhill, & Garnham, 2011): grammatical gender (e.g., French), combination of grammatical and natural gender (e.g., Norwegian), natural gender (e.g., English), and genderless (e.g., Finnish). In grammatical-gender languages, nouns are classified for gender. For inanimate nouns, the assignment of a grammatical gender is arbitrary. However, for nouns that refer to humans, grammatical gender agrees to a large extent with the referents’ biological gender (e.g., “la musicienne” f vs. “le musicien” m). In natural-gender languages, there is no classification of nouns, but a distinction appears in personal pronouns (e.g., “the musician . . . she” vs. “the musician . . . he”), and in genderless languages (e.g., Finnish “muusikko . . . hän”), neither nouns nor pronouns are marked to indicate a human referent’s biological gender.

Although grammatical gender is a device that can reflect the gender of a human noun referent, it does not always do so. More specifically, since some grammatical-gender languages do not have a word class of “both genders” or “irrelevant gender,” one grammatical gender typically serves this function (e.g., masculine, or less frequently feminine, forms are used generically). This twofold use of one grammatical word class (masculine nouns referring to males vs. masculine nouns referring to a person whose sex is unknown or irrelevant or to a group composed of both sexes) results in semantic ambiguity, which in turn is typically resolved to the disadvantage of women (Gygax et al., 2012; Gygax, Gabriel, Sarrasin, Garnham, & Oakhill, 2009). Using only the masculine form in grammatical-gender languages when assessing the conceptual properties of role nouns, such as their gender stereotypicality, is therefore misleading, since it may increase the representation of men in the examined occupations or social activities (Gabriel, Gygax, Sarrasin, Garnham, & Oakhill, 2008). As a consequence, in our questionnaire all role nouns are presented in both the masculine and feminine forms in grammatical-gender languages and are lexically specified for gender in natural-gender and genderless languages.

Gender stereotypicality refers to generalized beliefs or expectations about whether a specific (social or occupational) role is more likely to be held by one gender or the other. The relatively automatic reliance on stereotypes when reading role nouns has been shown in many studies, in social psychology (e.g., Banaji & Hardin, 1996) as well as psycholinguistics (e.g., Oakhill, Garnham, & Reynolds, 2005). However, although stereotype information has strong implications for the mental representation of role nouns in natural-gender or genderless languages (such as English), its role is under debate in the literature on grammatical-gender languages (e.g., Carreiras et al., 1996; Gygax et al., 2008; Irmen & Kurovskaja, 2010). In fact, though the sequence of activation of grammatical cues and stereotype information is still not clear (see Irmen, 2007, for an interesting proposition), it is generally agreed that stereotype information is always activated. Therefore, any investigation of the mental representation of gender, regardless of the language’s grammatical gender status, requires that stereotype norms be collected.

Regrettably, procedures have varied considerably across languages and studies, thus rendering it difficult to compare the results of the studies and their interpretations. For example, Carreiras et al. (1996) collected norms by asking participants to indicate the likelihood that a man or a woman would carry out the role presented. A total of 120 occupational nouns were rated by 30 English-speaking participants on an 11-point Likert scale (1 = strongly male to 11 = strongly female). A total of 16 Spanish speakers were asked to rate a total of 200 nouns. The Spanish role nouns were also rated on an 11-point scale, albeit one presented in the reverse direction (0 = strongly female to 10 = strongly male). In a pretest to their reading study investigating grammatical gender and gender representation, Irmen and Kurovskaja (2010) asked 30 German-speaking participants to rate role nouns according to their typicality on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = typically female to 7 = typically male). Their list included 63 occupational role nouns, which were presented in the masculine and feminine forms. In Finnish, Pyykkönen, Hyönä, and van Gompel (2010) asked 20 participants to rate 124 occupational nouns in terms of masculinity and femininity on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = extremely masculine to 7 = extremely feminine). Kennison and Trofe (2003) collected data to establish a set of stereotype norms for 405 role nouns. They presented the list of role nouns to their 80 English-speaking participants and asked them to estimate the likelihood that these would represent a woman, man, or both. It was further stressed that participants should give their own opinions. Scale direction was manipulated, and participants were presented with a version of the questionnaire either with 1 corresponding to mostly female and 7 to mostly male (Version 1), or with the reversed order in Version 2 (i.e., 1 = mostly male to 7 = mostly female). Although no order effect was apparent in this study, more recently, Gabriel et al. (2008), using a similar design, did find an order effect by reversing scale direction. In their study, Gabriel et al. collected role noun norms for 126 nouns (most of which were from Kennison & Trofe, 2003) in English, French, and German. They presented the nouns along with an 11-point scale (from 0 % women and 100 % men to 100 % women and 0 % men, with 10 % incremental increases), and the participants had to respond by rating the extent to which the presented social and occupational groups actually consisted of women and men. An additional aspect of the Gabriel et al. study was the use of four versions of the questionnaire: the role noun in the feminine form on the left and the role noun in the masculine form on the right (Version I); the role noun in the masculine form on the left and the role noun in the feminine form on the right (Version II); the role noun only in the masculine form (i.e., generic) on the left (Version III); or the role noun only in the masculine form (i.e., generic) on the right (Version IV). Participants given Version I estimated that more women filled the roles, relative to those who saw Version II. Importantly, the effect was stable across all the languages in terms of reading direction (i.e., we read from left to right in all three languages tested) and an anchoring effect on the first role noun read.

Though all of the procedures presented above have provided researchers with legitimate data on which to base their subsequent experiments, the diversity of these procedures (i.e., questionnaires and rating scales of various types) forces us to consider cross-linguistic studies and comparisons of the languages tested with caution. This is not to say that such comparisons are unreasonable, or cannot provide useful insights, but we believe that a standardized procedure for collecting stereotype norms across languages and research teams is central to extending and interpreting results appropriately across studies.

In this article, we offer a possible solution to this issue, by providing (a) recent norms on up to 422 role nouns (depending on the language), collected across seven languages, using a standard procedure based on those discussed above; as well as (b) a Web-based platform for researchers to use when collecting norms for use in future studies on all matters related to the representation of gender and stereotypes.

Method

Participants

Overall sample

A total of 1,663 participants contributed to this study. The data of 255 participants were removed because they were not native speakers of the target languages (N = 107), were not students (N = 126), or did not comply with the instructions (N = 22). The remaining 1,408 participants’ data were used for further analysis.

Czech-speaking sample

The data from 72 participants (six male, 66 female) with an age range from 19 to 30 years (M = 21.57, SD = 2.05) were collected at the University of Budweis (Czech Republic). All participants were offered an entry in a prize draw for filling in the questionnaire.

English-speaking sample

The data from 281 participants (42 male, 238 female, and one not specified) were collected at the University of Sussex (Brighton, UK). Participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 51 years old (M = 20.37, SD = 4.39). The students received course credits for participation.

French-speaking sample

A group of 65 French-speaking participants from Switzerland (17 male, 48 female) with an age range from 18 to 44 years (M = 21.11, SD = 3.28) were recruited at the University of Fribourg (French-speaking part of Switzerland). The students received course credit for participation.

German-speaking sample

A group of 70 German-speaking participants from Germany (ten male, 58 female, and two other/not specified) were recruited, mainlyFootnote 1 at the Free University of Berlin (N = 44), and the University of Duisburg-Essen (N = 15). Students participated without compensation at both universities. Participants’ ages ranged from 21 to 34 years old (M = 24.23, SD = 2.95).

Italian-speaking sample

A group of 800 Italian participants (247 male, 553 female) were recruited at the Universities of Padova and Modena (Italy). Participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 64 years old (M = 22.86, SD = 4.15); they received no compensation.

Norwegian-speaking sample

A group of 60 participants (14 male, 46 female) were recruited at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim and participated without compensation. Participants’ ages ranged from 19 to 52 years old (M = 24, SD = 6.56).

Slovak-speaking sample

A group of 60 participants (nine male, 51 female) were recruited at Constantine the Philosopher University in Nitra (Slovakia) and participated voluntarily. The participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 41 years old (M = 22.48, SD = 3.23).

Questionnaire and design

On the basis of previous norming studies (Gabriel et al., 2008; Kennison & Trofe, 2003) and of brainstorming sessions and trawls of dictionaries, 422 English role nouns were selected that were likely to have equivalent words across all or most of the tested languages. The questionnaire was administered in seven languages: Czech (grammatical gender), English (natural gender), French (grammatical gender), German (grammatical gender), Italian (grammatical gender), Norwegian (combination of grammatical and natural gender), and Slovak (grammatical gender). Translations were carried out by the authors and double-checked by SMG UK Translations Limited, a professional translation company. Because of different-sized vocabularies, the number of role nouns differed across the languages, ranging from the full set of 422 role nouns in English to 398 role nouns in Norwegian (see Appendix A for a complete list of the role nouns). The choice of languages was determined by the composition of the Marie Curie Initial Training Network (www.itn-lcg.eu), Language, Cognition, and Gender, and by whether the academic partners had ready access to student populations from which to collect data.

As in Gabriel et al. (2008), participants had to estimate the extent to which the presented social and occupational groups actually consisted of women and men (i.e., the ratio) on an 11-point rating scale ranging from 0 % women and 100 % men to 100 % women and 0 % men, with 10 % incremental increases. The scale was provided in terms of two scale directions: one version with 100 % women and 0 % men on the right of the scale (Version 1), and another with 100 % women and 0 % men on the left (Version 2).

For the grammatical-gender languages (i.e., Czech, French, German, Italian, and Slovak), role nouns were presented in both masculine and feminine plural forms (as in Versions I and II of Gabriel et al., 2008). For role nouns with no distinctive masculine or feminine markings in grammatical-gender languages (e.g., in Italian, insegnante [teachers]) and for role nouns in the natural-gender languages (i.e., English and Norwegian), the words women and men were added at the end of the role nouns in brackets—for example, firefighters (women) versus firefighters (men).

Since the number of role nouns to be evaluated was high, each participant evaluated only half of the role nouns (up to 211, depending on the language). For each participant, we wanted those role nouns to be randomly chosen from the full set of role nouns. To our knowledge, most existing online questionnaire systems (e.g., survey systems) have not allowed for random stimulus allocation. Adding to this specific procedural constraint were the facts that two scale directions were possible, which might produce different results (Gabriel et al., 2008), and that overall, we wanted all role nouns to be responded to equally often (i.e., equal sample sizes). Therefore, we could not rely on existing resources and had to spefically program our own Web-based system.

The role noun allocation was as follows: For the first participant (and a given language), the system randomly selected half of the role nouns from the full list and presented them in a random order in a randomly selected scale direction. The remaining half of the role nouns were presented in a random order to the second participant. The third participant evaluated the same role nouns in the same order as the first participant, though in the other scale direction, and the fourth participant evaluated the same role nouns in the same order as the second participant, though in the other scale direction. The system then started the procedure again for the following four participants. In other words, a particular random seed was associated with four participants. Note that within a group of four participants, uncompleted questionnaires were saved separately (and, in the present study, not analyzed). Another participant would then be allocated the questionnaire that was incomplete and would complete it independently. This process was iterated until complete versions of all four related questionnaires had been collected.

Procedure

The questionnaire was administered online via a webpage created for the sole purpose of this project (https://www.unifr.ch/lcg). On a first screen, participants stipulated their native language, on which the following questionnaire was going to be based. They then read the instructions and a consent form in that language. By clicking Enter, they agreed to the conditions of participation, and a screen asking for demographics (age, gender, and profession) followed. Once the demographic data were entered, participants were asked to estimate, on an 11-point scale, the extent to which the presented social and occupational groups actually consisted of women and men (i.e., the ratio) (see Fig. 1). Participants were instructed to estimate the extent to which the groups depicted by the role nouns are actually made up of women and men, rather than being influenced by any thoughts of how these proportions ought to be. Role nouns were presented in sets of a maximum of 20 role nouns per page.

Results

All questionnaires were coded such that high values on the 11-point scale reflected a higher proportion of women. The data were transformed into proportions, such that “100 % women and 0 % men,” for example was recoded as 1, “50 % women and 50 % men” as .5, and “0 % women and 100 % men” as 0.

By-participants analyses

For each language, by-participants analyses were carried out on the mean ratings for each person tested, averaged across (classes of) items. These analyses investigated (1) the mean bias of all of the items tested for each language, (2) whether the people completing different versions of the questionnaire judged, on average, that the same proportions of females and males filled various roles (i.e., did the format of the questionnaire affect the resulting norms?), and (3) whether male and female participants differed, on average, in the proportions of females and males that they judged to fill various roles.

Czech

For each participant, the mean rating across the role nouns was calculated (M = .43, SD = .05; scale midpoint = .50). These normally distributed scores, Kolmogorov–Smirnov’s D(72) = .10, p = .18, ranged from .31 to .54. The mean rating for Version 1 (100 % feminine–right) was .42 (SD = .04), whereas the mean for Version 2 (100 % feminine–left) was .43 (SD = .05). A t test revealed that the difference between the two scales was nonsignificant, t(70) = 0.52, p = .606. Overall, female respondents rated the proportion of women as being slightly higher (M = .43, SD = .05) than did male participants (M = .41, SD = .07), t(70) = 0.71, p = .48.

English

For each participant, the mean rating across the role nouns was calculated (M = .44, SD = .04; scale midpoint = .50). Though the overall distribution of scores was nonnormal, D(281) = .06, p = .007, ranging from .33 to .54, only the distribution of Version 1 was nonnormal, D(141) = .09, p = .007. The mean rating for Version 1 (100 % feminine–right) was .43 (SD = .04), whereas the mean for Version 2 (100 % feminine–left) was .45 (SD = .03). A t test revealed a significant difference between the two scales, t(279) = 3.25, p = 001, meaning that the feminine form on the left resulted in significantly more women being estimated to carry out the role presented. Overall, female (M = .44, SD = .04) and male (M = .44, SD = .04) respondents rated the proportions of women as being equally high, t(278) = −0.56, p = .57.

French

For each participant, the mean rating across the role nouns was calculated (M = .42, SD = .04; scale midpoint = .50). These normally distributed scores, D(65) = .06, p > .20, ranged from .32 to .50. The mean rating for Version 1 (100 % feminine–right) was .42 (SD = .04), and an identical mean and variance were found for Version 2 (100 % feminine–left), t(63) = 0.09, p = .93. Overall, female (M = .42, SD = .03) and male (M = .42, SD = .05) participants rated the proportions of women similarly, t(63) = 0.25, p = .81.

German

For each participant, the mean rating across the role nouns was calculated (M = .44, SD = .04; scale midpoint = .50). Though the overall distribution of scores was nonnormal, D(70) = .11, p = .045, ranging from .35 to .50, the distributions of both Version 1 and Version 2 were normal. The mean ratings for Version 1 (100 % feminine–right: M = .44, SD = .03) and Version 2 (100 % feminine–left: M = .44, SD = .04) did not differ, t(68) = 0.71, p = .48. Overall, female participants rated the proportion of women as being slightly higher (M = .45, SD = .03) than did male participants (M = .42, SD = .04), t(66) = 1.87, p = .066, yet this difference needs to be considered with caution, due to the unequal sample sizes (i.e., ten male, 58 female).

Italian

For each participant, the mean rating across the role nouns was calculated (M = .43, SD = .04; scale midpoint = .50). Though the overall distribution of scores was nonnormal, D(800) = .04, p = .009, ranging from .26 to .55, only the distribution of Version 1 was nonnormal, D(141) = .05, p = .04. The mean rating for Version 1 (100 % feminine–right) was .42 (SD = .04), whereas the mean for Version 2 (100 % feminine–left) was .44 (SD = .04). A t test revealed a significant difference between the two scales, t(798) = 5.59, p < 001. Overall, the female participants (M = .43, SD = .04) and male participants (M = .43, SD = .04) rated the proportions of women similarly, t(798) = 0.48, p = .630.

Norwegian

For each participant, the mean rating across the role nouns was calculated (M = .44, SD = .03; scale midpoint = .50). These normally distributed scores, D(60) = .08, p > .20, ranged from .36 to .50. The mean rating for Version 1 (100 % feminine–right) was .43 (SD = .04), whereas the mean for Version 2 (100 % feminine–left) was .45 (SD = .03). A t test revealed a significant difference between the two scales, t(58) = 2.62, p = .011, meaning that the feminine-on-the-left version resulted in significantly more women being estimated to carry out the role presented. Overall, female (M = .44, SD = .04) and male (M = .44, SD = .02) participants rated the proportions of women similarly, t(58) = −0.29, p = .771.

Slovak

For each participant, the mean rating across the role nouns was calculated (M = .42, SD = .05; scale midpoint = .50). These normally distributed scores, D(60) = .11, p = .084, ranged from .27 to .50. The mean rating for Version 1 (100 % feminine–right) was .41 (SD = .05), whereas the mean for Version 2 (100 % feminine–left) was .43 (SD = .04). A t test revealed that the difference between the two scales was nonsignificant, t(58) = 1.66, p = .103. Overall, female participants rated the proportion of women as being slightly higher (M = .42, SD = .05) than did male participants (M = .41, SD = .05), t(58) = 0.97, p = .339, though, as with the German sample, this difference needs to be considered with caution because of unequal sample sizes (i.e., nine male, 51 female).

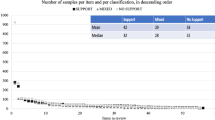

By-items analyses

For each language, the mean proportions of females and males judged to fill each role were calculated. These proportions (see Appendix B), together with the standard deviations and the number of responses for each item, can be used to assess whether the terms are stereotyped. To be more precise, the standard deviations indicate the level of consensus across participants in our samples, but a measure such as the standard error of the mean or a confidence interval around the mean would be needed to show whether we had evidence that the mean for a particular item in a particular language was different from .5 (the midpoint on the scales, corresponding to 50 % females and 50 % males).

These proportions also allow the computation of correlations, both for the scores on cognate items in different languages and for scores on the same items in different versions of the questionnaire within a language. As is shown in Table 1 (the Ns of the role nouns differ due to different-sized vocabularies), the mean ratings per role noun were highly reliable across all languages, all ps < .01, indicating a high consensus across languages. Similarly, the mean ratings per role noun were highly reliable across scale directions, with an overall correlation of r s = .99 (p < .001).

Discussion

The aim of this article was twofold. First, we wanted to provide norms for a large number of role nouns and from a large number of respondents (i.e., many more than have been included in previous norming studies) across several languages, using one fixed methodology. Second, we wanted to offer a Web-based platform for collecting norms for use in future studies on all matters surrounding the representation of gender and gender stereotypes.

With reference to the primary aim, several aspects of our data deserve comment. First, and mimicking the results found by Gabriel et al. in 2008, the rankings of the role nouns were very similar across languages, as is attested by the high correlations between languages and the similarity in the overall proportion means. Second, and related to the first aspect, the overall proportion of women in the role nouns ranged from .42 to .45 across languages, signaling globally stronger male stereotypes than female, which is also consistent with the previous norms (e.g., Gabriel et al., 2008). Third, though women participants indicated overall that they thought slightly higher proportions of women filled the roles (as compared to the male participants, the greatest difference being in German), these differences were never significant, so we have no evidence of a sex-of-respondent effect. Fourth, and finally, scale direction is a factor that should be taken into consideration, inasmuch as proportions of women are generally higher (significantly so in English, Italian, and Norwegian) when 100 % feminine is displayed on the left of the screen, rather than the right. However, since this effect is numerically small and has little effect on the relative ordering of the role names for stereotypicality, it may only be important in some circumstances (e.g., when looking at role nouns individually).

Concerning the second aim of the study, we suggest that use of the same norming methodology across all research teams interested in research on gender and stereotyping might prove beneficial in several ways. First, it will enable relatively unproblematic cross-experiment comparisons, especially when addressing issues related to stereotypes. Second, and more specifically, it will facilitate cross-linguistic comparisons and longitudinal comparisons that can investigate the evolution of role nouns’ gender stereotypicality. As in the present article, cross-language comparisons will still require some caution: In some cases, though words are grounded on the same cognates (e.g., vice chancellor in English vs. Vizekanzler in German), they do not necessarily refer to the exact same role, and in some cases, an occupation may be referred to by several names in a given language (at some level of specificity), whereas it might only be referred to with one name in another language. Though this seems like an obvious point, it still needs to be addressed when examining stereotypicality cross-linguistically.

In addition to the limitations mentioned above, we would add those naturally associated with the use of the Internet for gathering data. The primary source of these limitations is the lack of control over the participants’ true behaviors when completing the questionnaire (i.e., responding randomly or dishonestly, or misrepresenting themselves in terms of language competences). Researchers concerned about these issues can decide to collect data in their own computer-based seminars or in other contexts, usually within their own institution, that will allow for better control over the testing phase. Additional information pertaining to specific research questions may then also be collected (e.g., language competences or social background). With these possibilities in mind, we believe that the possible limitations of the use of a computer-based questionnaire for norming role nouns are outweighed by its advantages. One of these advantages is the possibility of (much more easily) testing a wide range of population samples, across ages, cultures, and countries. In essence, considering that the Internet has now become a relatively common medium, we believe that having a Web-based questionnaire to evaluate role noun stereotypicality can potentially address a wider range of issues than could traditional paper-based questionnaires.

One important issue that the present study has not addressed, and that may be considered in future studies, is the extent to which the ratings obtained, which can be considered as being relatively good estimates of people’s beliefs, are close to real gender distributions in the occupations or other social roles. Though for several role nouns real-world information may be difficult to obtain, for many it should be relatively easily available (e.g., from national statistics). Similarities as well as dissimilarities between beliefs and the actual distributions could be of great interest. For example, such information may shed light on the difference between typicality and stereotypicality.

As a final important note, the Web-based questionnaire currently has matched sets of role nouns for Basque, Czech, English, Farsi, French, German, Italian, Mandarin, Norwegian, Slovak, and Spanish. Researchers interested in collecting norms in any of these languages can contact the second author of this article. Data collection will be run at the institution of the research team interested in these norms by providing participant access to the Web address mentioned in the Method section. Data can be sent to the research team in Excel format once the data collection is completed. For those interested in adding languages, some development fees may have to be applied.

Notes

Two of the German students were from the University of Fribourg (Switzerland), one from the University of Düsseldorf (Germany), one from the Hochschule Zittau (Germany), one from the Technische Universität Dresden (Germany), one from Humboldt-Universität (Germany), and five students did not specify their affiliations.

References

Banaji, M., & Hardin, C. (1996). Automatic stereotyping. Psychological Science, 7, 136–141.

Braun, F., Oakhill, J., & Garnham, A. (2011, June). The language gender index. Paper presented at the Language, Social Roles, and Behavior LCG-ITN Summer School, Berlin, Germany.

Carreiras, M., Garnham, A., Oakhill, J., & Cain, K. (1996). The use of stereotypical gender information in constructing a mental model: Evidence from English and Spanish. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 49A, 639–663.

Gabriel, U., Gygax, P., Sarrasin, O., Garnham, A., & Oakhill, J. (2008). Au-pairs are rarely male: Role nouns’ gender stereotype information across three languages. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 206–212.

Gygax, P., Gabriel, U., Lévy, A., Pool, E., Grivel, M., & Pedrazzini, E. (2012). The masculine form and its competing interpretations in French: When linking grammatically masculine role nouns to female referents is difficult. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 24, 395–408.

Gygax, P., Gabriel, U., Sarrasin, O., Garnham, A., & Oakhill, J. (2009). Some grammatical rules are more difficult than others: The case of the generic interpretation of the masculine. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 24, 235–246.

Gygax, P., Gabriel, U., Sarrasin, O., Oakhill, J., & Garnham, A. (2008). Generically intended, but specifically interpreted: When beauticians, musicians and mechanics are all men. Language and Cognitive Processes, 23, 464–485.

Irmen, L. (2007). What’s in a (role) name? Formal and conceptual aspects of comprehending personal nouns. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 36, 431–456.

Irmen, L., & Kurovskaja, J. (2010). On the semantic content of grammatical gender and its impact on the representation of human referents. Experimental Psychology, 57, 367–375.

Kennison, S. M., & Trofe, J. L. (2003). Comprehending pronouns: A role for word-specific gender stereotype information. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 32, 355–378.

Oakhill, J., Garnham, A., & Reynolds, D. (2005). Immediate activation of stereotypicalgender information. Memory & Cognition, 33, 972–983.

Phillips, W., & Boroditsky, L. (2003). Can quirks of grammar affect the way you think? Grammatical gender and object concepts. In R. Alterman & D. Kirsh (Eds.), Proceedings of the 25th Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Pyykkönen, P., Hyönä, J., & van Gompel, R. P. G. (2010). Activating gender stereotypes during online spoken language processing: Evidence from visual world eye tracking. Experimental Psychology, 57, 126–133.

Slobin, D. I. (1996). From “thought and language” to “thinking for speaking. In J. J. Gumperz & S. C. Levinson (Eds.), Rethinking linguistic relativity (pp. 70–96). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Stahlberg, D., Braun, F., Irmen, L., & Sczesny, S. (2007). Representation of the sexes in language. In K. Fiedler (Ed.), Social communication (pp. 163–187). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Author note

The research reported in this article was funded by the European Community’s Seventh Framework Program (FP7/2007-2013) under Grant Agreement nº 237907 (Marie Curie ITN, Language, Cognition, and Gender). We thank Maurizio Rigamonti for his invaluable help on setting up the questionnaire website.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A

Appendix B

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Misersky, J., Gygax, P.M., Canal, P. et al. Norms on the gender perception of role nouns in Czech, English, French, German, Italian, Norwegian, and Slovak. Behav Res 46, 841–871 (2014). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-013-0409-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-013-0409-z