Abstract

Background

Pneumoparotid is a rare cause of parotid gland swelling. It is due to reflux of air through Stensen’s duct into the parenchyma of the parotid gland.

Case presentation

A case of self-induced pneumoparotid in a 12-year-old boy is reported. The diagnosis was primarily considered after careful history taking with special attention on the patient’s habits, and it was confirmed by computed tomography.

Conclusion

Pneumoparotid is a rare but well-documented clinical entity. It should be included in the differential diagnosis of parotid gland swelling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pneumoparotid is a rare cause of parotid gland swelling. It describes the presence of air within the duct system and/or parenchyma of the parotid gland secondary to its reflux through Stensen’s duct [1, 2].

It was first described by Hyrtel in 1865 [1], and since then, sporadic cases were reported in the literature under various synonyms like pneumoparotitis, wind parotitis, pneumosialadenitis, and anesthetic or surgical mumps.

In the literature, the two terms: pneumoparotid and pneumoparotitis are used interchangeably which should not be the case as pneumoparotid seems to be the most appropriate term to describe the presence of air within the parotid gland in the absence of inflammation or infection [3].

Pneumoparotid has been reported to occur as an isolated transient event (as seen post dental procedures using air-powered equipments and post positive pressure ventilation). It has also been reported as an occupational hazard in glass-blowers, wind instrument players, and scuba divers [4]. Non-occupational self-induced pneumoparotid is the most frequently reported clinical entity, and it is most commonly reported in children and adolescents with psychosocial problems who induce parotid insufflation to avoid school or gain attention [5,6,7].

Case presentation

A 12-year-old boy was referred to the ENT clinic with history of recurrent painless left parotid swelling of 3 months duration. Swelling was not related to food intake. There was no history of fever, malaise, or recent dental treatment. Past medical and psychosocial histories were unremarkable.

The boy was well-looking and afebrile. Parotid examination revealed a 2 × 2 cm soft-firm well-circumscribed left parotid mass with no signs of acute inflammation. Clear saliva was seen to flow from the parotid duct orifice on both sides. Facial nerves were intact. Examination of the throat, nose, ears, and neck was unremarkable.

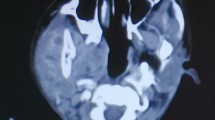

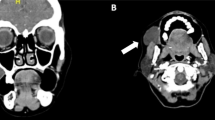

Full blood count, ESR, renal function test, liver function test, and serum electrolytes were all normal. Computed tomography (CT) demonstrated the presence of a rounded air-filled left parotid mass with left temporal subcutaneous emphysema (Fig. 1). CT scan was repeated during Valsalva maneuver, and it showed an additional bilateral dilatation of the Stensen’s duct (Fig. 2).

On further questioning, the boy admitted the habit of balloon-blowing. The clinical condition was explained fully to the patient and his father, and the boy was advised to avoid the precipitating factor (balloon-blowing). Over 2 days, the parotid swelling and its associated subcutaneous emphysema spontaneously resolved. The boy remained symptomless for a follow-up period of 2 years.

Discussion

Under physiological conditions, air and oral secretions are prevented from flowing back into the parotid duct and gland by various anatomical mechanisms: contraction of the buccinator muscle [8], the diameter of the duct orifice is less than that of the duct itself [7, 9], the duct orifice is slit-shaped and is sealed off by mucosal folds when intraoral pressure increases [4, 5], cheek inflation increases duct angle both between the oral submucosa and buccinator muscle and between the buccinator and the subcutaneous tissue alongside the masseter muscle.

When intraoral pressure increases from 2–3 mm Hg as in normal breathing to 140–150 mm Hg as in glass-blowing and wind instrument playing, air may be insufflated into the parotid glands causing pneumoparotid.

There are other precipitating factors of pneumoparotid like dental procedures using air-powered equipments, cough in COPD and cystic fibrosis, forceful nose blowing, balloon-blowing, Valsalva maneuver, positive pressure ventilation, and anatomical abnormalities including patulous Stensen’s duct, masseter muscle hypertrophy, and buccinator muscle weakness [1, 7, 10].

Patients with pneumoparotid typically present with unilateral or bilateral painless swelling and tenderness in the parotid region. Crepitus over the parotid gland can be demonstrated in about 50% of cases. Frothy air-filled saliva can be observed to flow from the parotid duct orifice upon the gland massage [5, 7].

Recurrent parotid insufflation may predispose to sialectasis; recurrent parotitis; and subcutaneous emphysema of the face, neck, and mediastinum; and subsequent pneumothorax [2].

Careful history taking and complete physical examination are key factors for diagnosis. Computed tomography (CT) scan is the gold standard radiological test for diagnosis as it shows air within the parotid gland, ducts, and neighboring structures in case of parotid fascia rupture and extension of the insufflation outside the parotid gland system. Sialography, ultrasonography, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are also helpful for diagnosis.

Treatment in the majority of cases is conservative, and it is directed toward elimination of the precipitating factors. Parotid swelling usually resolves spontaneously in 1–3 days. Depending on the patient’s condition other measures can be taken, including analgesics, gland massage, hydration, and warm compresses. Prophylactic antibiotics have been used by some clinicians to prevent secondary infection. People at risk of developing occupational pneumoparotid can be taught techniques to reduce their chances of insufflation. In case of self-induction, reassurance and psychological counseling are often required [2].

Surgical interventions including Stensen’s duct ligation, transposition of the Stensen’s duct to the tonsillar fossa, and parotidectomy [6, 10] can be considered for recurrent pneumoparotid associated with sialectasis and recurrent parotitis not responding to conservative measures.

Conclusion

Pneumoparotid is a rare but well-documented cause of parotid gland swelling. Careful history taking with special attention on the patient’s habits and psychosocial aspects is an important key for diagnosis.

Pneumoparotid should be included in the differential diagnosis of parotid gland swelling especially in children and adolescents.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed in this scientific material are included in this published report and are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ENT:

-

Ear, nose, throat

- ESR:

-

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

References

Markowitz-Spence L, Brodsky L, Seidell G, Stanievich JF (1987) Self-induced pneumoparotitis in an adolescent. Report of a case and review of the literature. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 14:113–121

Gazia F, Freni F, Galletti C, Galletti B, Meduri A, Galletti F (2020) Pneumoparotid and pneumoparotitis: a literary review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(11):3936

Rupp RN (1963) Pneumoparotid. Arch Otolaryngol 77:111–114

Han S, Isaacson G (2004) Recurrent pneumoparotid: cause and treatment. Otolaryngol Neck Surg 131:758–761

Martín-Granizo R, Herrera M, García-González D, Mas A (1999) Pneumoparotid in childhood: report of two cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 57:1468–1471

Greisen O (1968) Pneumatocele glandulae parotis. J Laryngol Otol 82:477–480

Goguen LA, April MM, Karmody CS, Carter BL (1995) Self-induced pneumoparotitis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 121:1426–1429

Ferlito A, Andretta M, Baldan M, Candiani F (1992) Non-occupational recurrent bilateral pneumoparotitis in an adolescent. J Laryngol Otol 106:558–560

Birzgalis AR, Curley JW, Camphor I (1993) Pneumoparotitis, subcutaneous emphysema and pleomorphic adenoma. J Laryngol Otol 107:349–351

Huang PC, Schuster D, Misko G (2000) Pneumoparotid: a case report and review of its pathogenesis, diagnosis and management. Ear Nose Throat J 79:316–317

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

Nil

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DSA: prepared the scientific material and formulated the draft manuscript. AM: shared in formulating the manuscript draft. YI: completed the final revision of the manuscript. OA: provided the technical support for writing the finalized manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Obtained

Consent for publication

Written consent was obtained from the father of the patient.

Competing interests

No competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Aljeaid, D., Mubarak, A., Imarli, Y. et al. Pneumoparotid: a rare but well-documented cause of parotid gland swelling. Egypt J Otolaryngol 36, 46 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43163-020-00053-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43163-020-00053-x