Abstract

Background

Acute complicated appendicitis is a common abdominal emergency in children. Unlike simple appendicitis, laparoscopic appendectomy has not been considered yet the first choice in management of complicated appendicitis. This prospective randomized controlled clinical trial was conducted at Pediatric Surgery Department, Zagazig University Hospitals, Egypt, during the period from December 2018 to August 2019. The aim of the study was to evaluate the role of laparoscopic appendectomy in such cases compared to open appendectomy.

Results

Sixty patients were included in the study, divided randomly into 2 equal groups: laparoscopic and open appendectomy groups. The mean operative time was significantly longer with laparoscopic appendectomy than open appendectomy, 85 vs. 61 min, respectively (p < 0.001**). The time taken to start oral intake was significantly shorter with laparoscopic appendectomy than open appendectomy, 1.9 vs. 2.73 days, respectively (p = 0.025*). The mean hospital stay was significantly lower with laparoscopic appendectomy than open appendectomy, 4.23 vs. 5.13, respectively (p = 0.044*). There were no statistical differences between the two groups regarding wound infection, occurrence of postoperative ileus, intraperitoneal collection, or readmission.

Conclusions

Laparoscopic appendectomy is safe, feasible, and effective procedure in the management of complicated appendicitis in children, with no evidence of any increase in the postoperative complications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Acute appendicitis is considered one of the most common abdominal emergencies in children [1]. There is a high probability for occurrence of complications in this age group due to delay in diagnosis as a result of difficulty in communication and misdiagnosing with the more common gastrointestinal disorders [2, 3].

Open appendectomy (OA) through McBurney’s incision [4] had been considered as the technique of choice in managing such cases for more than one century. Introduction of minimal invasive surgery provided many benefits that made most surgeons try to consider it an alternative procedure in different surgical situations [2].

The first laparoscopic appendectomy (LA) was performed by Semm, a German gynecologist in 1983 [5], while the first LA in children was performed in 1992 by Ure and coworkers [6]. Since that, many trials reported good outcomes with LA for uncomplicated appendicitis due to its advantages, especially faster return to normal activity, less postoperative pain, and decreased postoperative complications [7].

The advantages of laparoscopic appendectomy in complicated appendicitis have been reported by many studies [8,9,10,11].

On the other hand, others reported some disadvantages including intra-abdominal abscess and wound infection, longer operative time, increased skill level needed, and higher costs [12,13,14].

Our work aims to compare the intraoperative and postoperative outcomes of LA versus OA in complicated appendicitis in children in our center.

Methods

After approval of the Institutional Review Board (ZU-IRB #4787/5-8-2018), registered 5 August 2018, a prospective randomized controlled clinical trial was conducted at Pediatric Surgery Department in our hospital during the period from December 2018 to August 2019. During the period of study, 60 patients were diagnosed and operated for complicated appendicitis based on history, clinical examination, laboratory findings, and ultrasonography. Patients with simple appendicitis or more than 12 years old were excluded.

Complicated appendicitis in this study was defined as acute appendicitis in which perforation with purulence or fecalith in the abdominal cavity or gangrenous appendicitis with or without intra-abdominal abscess.

LA was performed to 30 of the included patients, and OA was performed to the other 30.

Data was collected regarding demographics, preoperative assessment, intraoperative findings, operative time, length of hospital stay, time taken to start oral intake, and occurrence of postoperative complications, including wound infection, intraperitoneal collection, ileus, and readmission.

All patients had general endotracheal anesthesia and muscle relaxant. A Foley’s catheter and a nasogastric tube were used when indicated. OA was performed conventionally through McBurney’s or Lanz’s incisions.

The operative time in this study was measured as the real time of operation, from the first skin incision to the last skin closure with exclusion of the time of anesthesia and preparation.

LA was performed using a two-handed, three trocar technique. After pneumoperitoneum had been performed, a 5-mm port was introduced for a laparoscopic camera through a semicircular incision to the upper edge of the umbilicus, and then inspection of abdomen was done. Two working ports were introduced under direct vision, one to the suprapupic region at the midline (5 mm) and the other to the left lower quadrant at the level of the iliac spine (5 mm or 10 mm if endoclips would be used). After finding the appendix, hook diathermy was used to divide the mesoappendix carefully from the distal end of the artery towards the cecal base. According to the surgeon preference, the base of appendix was ligated with intracorporial sutures, a laparoscopic pre-tied loop sutures in small children, or endoclips via clip applier 10 mm in older children, and then the appendix was sharply divided between them and removed through the port.

Suction/irrigation was carried out if needed using sufficient saline solution till the aspirate become clear. Intra-abdominal drains were placed only on necessary when there were multiple pockets of collection.

All patients received intravenous antibiotics (cefotaxime, a third generation cephalosporin, 100 mg/kg/day), metronidazole (7.5 mg/kg/q 8 h), and analgesia (Paracetamol, 15 mg/kg/q 6 h). When the bowel function was restored, oral intake was started as soon as patients could tolerate it. Drain was removed usually after 48–72 h if there was no discharge and the abdomen of patient was lax and not distended. Patients were discharged after remaining afebrile for 24 h and after they can tolerate normal diet and exhibited a decrease in the white blood cell count to the normal level. The patients were followed up in the outpatient clinic at 1 week, 2 weeks, and at 1 month intervals for 3 months.

The collected data was analyzed using the software SPSS version 20. Quantitative variables were described using their means and standard deviations. Categorical variables were described using their absolute frequencies and were compared using Chi square test and Fisher exact test when appropriate. Independent sample t test (used with normally distributed data) was used to compare means of two groups. The level statistical significance was set at 5% (p < 0.05). Highly significant difference was present if p ≤ 0.001.

Results

A total of 60 patients were included in the study, 30 of them were managed with OA, and the other 30 were managed with LA. Demographic data showed no significant difference between the two groups (Table 1).

According to the latest update of definition of sepsis (sepsis-3), which is a life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection [15], there were no cases of sepsis regarding both groups. No cases were presented with intestinal obstruction in both groups.

There were 12 cases of perforated appendix, 10 suppurative appendicitis, and 8 gangrenous appendicitis in OA group, and 11 cases of perforated appendix, 12 suppurative appendicitis, and 7 gangrenous appendicitis in LA group. Operative time was significantly longer in with LA; its mean was 85.17 ± 27.02 min vs. 61.33 ± 20.08 min with OA (p < 0.001**). Intraperitoneal drain was inserted in 33.3% of LA cases vs. 76.6% of OA cases, which was statistically significant. There were 2 cases that had not been completed laparoscopically and converted to open approach. Patients could tolerate oral intake after (2.37 ± 0.85 days) OA group vs. (1.9 ± 0.71 days) in LA group, which was significantly faster with LA (p = 0.025*). Hospital stay was significantly shorter with LA (4.23 ± 1.57 days) vs. (5.13 ± 1.81 days) in OA group (Table 2).

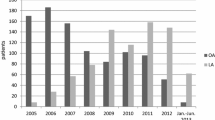

The rate of wound infection was lower in LA group than OA group, but the difference was not significant (20% vs. 26.7% respectively, p = 0.542). There was no significant difference between the LA and OA groups regarding occurrence of postoperative intraperitoneal collection (6.3% vs. 10% respectively) or ileus (3.3% vs. 6.3% respectively). There was also non-significant difference between the two groups regarding readmission (3.3% in LA group vs. 6.3% in OA group) (Fig. 1).

Discussion

Introduction of minimal invasive surgery made a revolution in the surgical practice as it provides many advantages over conventional surgeries. LA has been reported as the best choice for managing uncomplicated pediatric appendicitis for many benefits such as early return to physical activity, reduced postoperative pain, and decreased postoperative complications. But, as regards complicated appendicitis, it shows controversy to take the decision of performing laparoscopy as distorted anatomy and severe inflammation are challenging [9, 16, 17].

Many studies reported the superiority of laparoscopy regarding surgical site infection, regaining of oral intake, length of hospital stay, and cosmesis. On the other hand, slight higher rates of intra-abdominal infection, increased costs, and increased operative time are also recorded, but with more experience, laparoscopic surgery could become faster than open one [18, 19].

The operative time was significantly longer with LA than OA by 23.48 min that was nearly similar to many published literature [7, 9, 20,21,22]. These results could be explained as laparoscopic approach needs more experience, skills, and training. Also dealing with complicated appendicitis needs meticulous dissection which needs furthermore skills and training.

The need for intraperitoneal drain insertion was significantly lower with LA than OA (p = 0.001). This significance was also reported by Horvath et al. [23]; we explained that the laparoscopic technique offers a good vision to the entire abdomen and that enables the surgeon to achieve a careful suction from every quadrant having collections.

Conversion from laparoscopic to OA occurred with 2 cases included in this study (6.7%); one of them, the appendix was inaccessible due to extensive adhesions, and the other was perforated closely to the cecum, and it was difficult to ligate the appendix. This rate of conversion was nearly the same with that published by Thomson et al. [24] which occurred with 5% of their cases. Other publications reported fewer rate of conversion from laparoscopic to open, such as Kassem et al. [25] who reported the conversion to open in 2.4% of cases. This rate may differ according to the severity of the individual case. Additionally, using “Ligasure®, Covidien, USA” was reported to decrease the rate of conversion to open, especially in case of gangrenous tissue [16].

The time taken to start oral intake was significantly shorter after LA than OA by 0.47 days, which was comparable to other published studies [9, 25]. This could be explained by the advantages of the laparoscopic technique which is less traumatic to the abdominal wall and peritoneal cavity, associated with lower chance for introducing foreign bodies, provides better ability for hemostasis and associated with quicker return of bowel motility.

The present study showed that the hospital stay was significantly shorter after LA than OA by (0.9 day), which was nearly similar to that reported by Xuan et al. in their meta-analysis [17] and also the recent Cochrane systemic review which was (0.8 day) in favor of LA [18]. These results could be explained as LA is associated with less surgical stress, early mobilization, early oral intake, and less postoperative pain.

Most of recent studies have reported the benefits of LA over OA regarding wound infection [7]. However, in this study, the rate of postoperative wound infection was not significantly different between the two groups (p = 0.542), but incidence rate was still lower after LA than OA (20% vs. 26% respectively), which was comparable to Lin et al. [26] and Khirallah et al. [20]. On the other hand, some studies reported a significant decrease in the incidence of wound infection with LA, such as Xuan et al. [17]. These results could be explained that they protect the extraction site of the appendix during LA by using retrieval bag, which was not used in our study.

Formation of postoperative intraperitoneal collection is one of the issues that had shown controversy. Many earlier studies mentioned a major concern about increasing rate of incidence after LA, such as Horwitz et al. [27] who reported the occurrence of postoperative intraperitoneal collection after 9% of OA cases vs. 41% of LA cases. Also Krisher et al [28] and Thomson et al [24] reported nearly similar results. With increasing the experience in using LA in pediatric complicated appendicitis, many recent studies such as Vahdad et al [29] and a meta-analysis performed by Xuan et al [17] proved that there was no significant difference between the two techniques in formation of postoperative intraperitoneal collection, which was aligning with our results. On the other hand, Khirallah et al. reported a significant increasing rate of postoperative intraperitoneal collection after OA (28.4%) and LA (7%) [20]. This controversy could not be explained only as a result of the operative technique, but there were other external factors that could influence the results, such as the level of experience of the surgeon, the severity of inflammation, the degree of intraperitoneal contamination, the time of diagnosis, and the time of intervention [17].

The incidence of postoperative ileus was higher after OA than LA (6.3% vs. 3.3% respectively); however, this difference was not statistically significant. This was comparable to other published studies [17, 30]. The reduced incidence of postoperative ileus after LA could be explained due to reduced manipulation of the bowel with hands, minor abdominal trauma, and less postoperative pain.

There were 3 cases of readmission in this study, 2 of them occurred after OA (6.3%); one was due to ileus, and the other was due to intraperitoneal collection. The third case occurred after LA (3.3%) due to intraperitoneal collection. All these cases were managed conservatively. There was no significant difference between the two groups regarding readmission (p > 0.999) and that was nearly similar to other publications [7, 12, 17].

Conclusions

Our study demonstrates that laparoscopic appendectomy is safe, feasible, and effective in the management of complicated appendicitis in children. Furthermore, it provides many advantages, including faster recovery, less need for drain insertion, less hospital stay, and less wound infection, with no evidence of any increase in the postoperative intraperitoneal infection, ileus, or readmission.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- LA:

-

Laparoscopic appendectomy

- OA:

-

Open appendectomy

- TLC:

-

Total leukocytic count

- vs.:

-

Versus

References

Peter SD ST., Wester T. Appendicitis. In: III GWH, Murphy JP, Peter SD St., editors. Holcomb and Ashcraft’s pediatric surgery. 7th China: Elsevier Inc.; 2020. p. 664–678.

Sullins VF, Lee SL. Appendicitis. In: Holcomb GW, Murphy JP, Ostlie DJ, editors. Ashcraft’s pediatric surgery. 6th. Elsevier; 2014. p. 568–579.

Brown RL. Appendicitis. In: Ziegler MM, Azizkhan RG, Men D von A, Weber TR, editors. Operative pediatric surgery. 2nd ed. Mc Graw Hill; 2014. p. 613–631.

McBurney C IV (1894) The incision made in the abdominal wall in cases of appendicitis, with a description of a new method of operating. Ann Surg 20(1):38–43. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000658-189407000-00004

Semm K (1983) Endoscopic appendectomy. Endoscopy. 15(2):59–64

Ure B, Spangenberger W, Hebebrand D, Eypasch E, Troidl H (1992) Laparoscopic surgery in children and adolescents with suspected appendicitis: results of medical technology assessment. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2(06):336–340 Available from: http://www.thieme-connect.de/DOI/DOI?10.1055/s-2008-1063473

Svensson JF, Patkova B, Almström M, Eaton S, Wester T (2016) Outcome after introduction of laparoscopic appendectomy in children: a cohort study. J Pediatr Surg 51(3):449–453. Available from:. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2015.10.002

Frazee RC, Bohannon WT (1996) Laparoscopic appendectomy for complicated appendicitis. Arch Surg 131:509–512

Wang X, Zhang W, Yang X, Shao J, Zhou X, Yuan J (2009) Complicated appendicitis in children : is laparoscopic appendectomy appropriate? A comparative study with the open appendectomy — our experience. J Pediatr Surg 44(10):1924–1927. Available from:. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.03.037

Zwintscher NP, Johnson EK, Martin MJ, Newton CR (2013) Laparoscopy utilization and outcomes for appendicitis in small children. J Pediatr Surg 48(9):1941–1945. Available from:. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2012.12.039

Chandler NM, Ghazarian SR, King TM, Danielson PD (2014) Cosmetic outcomes following appendectomy in children: a comparison of surgical techniques. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech 24(8):584–588 Available from: http://online.liebertpub.com/doi/abs/10.1089/lap.2014.0061

Michailidou M, Goldstein SD, Sacco Casamassima MG, Salazar JH, Elliott R, Hundt J et al (2015) Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy in children: the effect of surgical technique on healthcare costs. Am J Surg 210(2):270–275. Available from:. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2014.09.037

Dai L, Shuai J (2017) Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy in adults and children: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. United European Gastroenterol J 5(4):542–553

Buicko JL, Parreco J, Abel SN, Lopez MA, Sola JE, Perez EA (2017) Pediatric laparoscopic appendectomy, risk factors, and costs associated with nationwide readmissions. J Surg Res 215:245–249. Available from:. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2017.04.005

Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour C, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M et al (2016) The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3). JAMA J Am Med Assoc 315(8):801–810

Di Saverio S, Birindelli A, Kelly MD, Catena F, Weber DG, Sartelli M et al (2016) WSES Jerusalem guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of acute appendicitis. World J Emerg Surg 11(34):1–25. Available from:. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-016-0090-5

Xuan Z, Glenn L, Bonney K, Bok J, So Y, Lincoln D et al (2019) Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy in pediatric patients with complicated appendicitis : a meta-analysis. Surg Endosc 33(12):4066–4077. Available from:. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-019-06709-x

Jaschinski T, Mosch CG, Eikermann M, Neugebauer EAM, Sauerland S (2018) Laparoscopic versus open surgery for suspected appendicitis (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 11:CD001546

Ahuja NR, Rothstein DH (2019) Surgical techniques in pediatric appendectomy. In: Controversies in pediatric appendicitis, Hunter CJ edn. Springer Nature Switzerland AG, pp 103–110

Khirallah MG, Eldesouki NI, Elzanaty AA, Ismail KA, Arafa MA (2017) Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy in children with complicated appendicitis. Ann Pediatr Surg 13:17–20

Tsai C, Lee S, Huang F (2012) Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy in the management of all stages of acute appendicitis in children : a retrospective study. Pediatr Neonatol 53(5):289–294. Available from:. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedneo.2012.07.002

Taguchi Y, Komatsu S, Sakamoto E, Norimizu S, Shingu Y, Hasegawa H (2016) Laparoscopic versus open surgery for complicated appendicitis in adults: a randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc 30(5):1705–1712 Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00464-015-4453-x

Horvath P, Lange J, Bachmann R, Struller F, Königsrainer A, Zdichavsky M (2017) Comparison of clinical outcome of laparoscopic versus open appendectomy for complicated appendicitis. Surg Endosc 31(1):199–205 Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00464-016-4957-z

Thomson JE, Kruger D, Jann-Kruger C, Kiss A, Omoshoro-Jones JAO, Luvhengo T et al (2015) Laparoscopic versus open surgery for complicated appendicitis : a randomized controlled trial to prove safety. Surg Endosc 29(7):2027–2032

Kassem R, Shreef K, Khalifa M (2017) Effects and clinical outcomes of laparoscopic appendectomy in young children with complicated appendicitis : a case series. Egypt J Surg 36:152–155

Lin H, Lai H, Lai I (2014) Laparoscopic treatment of perforated appendicitis. World J Gastroenterol 20(39):14338–14347

Horwitz JR, Custer MD, May BH, Mehall JR, Lally KP (1997) Should laparoscopic appendectomy be avoided for complicated appendicitis in children? J Pediatr Surg 32(11):1601–1603

Krisher SL, Browne A, Dibbins A, Tkacz N, Curci M (2001) Intra-abdominal abscess after laparoscopic appendectomy for perforated appendicitis. Arch Surg 136(4):438–441

Vahdad MR, Troebs R, Nissen M, Burkhardt LB, Hardwig S, Cernaianu G (2013) Laparoscopic appendectomy for perforated appendicitis in children has complication rates comparable with those of open appendectomy. J Pediatr Surg 48(3):555–561. Available from:. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2012.07.066

Chang HK, Han SJ, Choi SH, Oh J (2013) Feasibility of a laparoscopic approach for generalized peritonitis from perforated appendicitis in children. Yonsei Med J 54(6):1478–1483

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The authors declare that they have not received any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MMS (the corresponding author) collected the data, searched for literature, and prepared the manuscript. AER performed the study design and supervised the clinical work. MK performed statistical analysis of the data and reviewed the literature search. HNA performed editing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This article was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Zagazig University (ZU-IRB #4787/5-8-2018). A written informed consent was obtained from all patients’ caregivers.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Seqsaqa, M., Rozeik, A.E., Khalifa, M. et al. Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy in complicated appendicitis in children: a single center study. Egypt Pediatric Association Gaz 68, 26 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43054-020-00034-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43054-020-00034-y