Abstract

To date, researchers have developed various animal models of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) to investigate its mechanisms and to identify potential therapeutic treatments. A widely recognized model that mimics the pathology of human sporadic AD involves intracerebroventricular (ICV) injection with streptozotocin (STZ). However, ICV injections are an invasive approach, which creates limitations in generalizing the results. In this study, we produced a rodent model of AD using STZ (3 mg/kg) injection via the cisterna magna (CM) once every week for 4 weeks, and analyzed at 4 weeks and 16 weeks after final injection. In the CM-STZ rodent model of AD, we observed increase in extracellular amyloid-beta (Aβ) deposition and decrease and abnormal morphology of post-synaptic protein, PSD95 in 16 weeks STZ-injected group. The model developed using our less-invasive method induced features of AD-like pathology, including significantly increased extracellular amyloid-beta deposition, and decreased synaptic protein in the hippocampus. These findings supporting the success of this alternative approach, and thus, we suggest this is a promising, less invasive model for use in future AD research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common neurodegenerative disorder causing dementia [1]. AD is pathologically characterized by amyloid-beta (Aβ) plaques, neuronal loss, and cognitive impairment [2]. Considerable research has been performed to develop AD models and conduct preclinical studies to investigate the mechanisms underlying AD and potential treatment options [3].

Streptozotocin (STZ) is a diabetogenic compound able to induce insulin-resistant cells similar to sporadic AD neural cells [4]. Therefore, intracerebroventricular (ICV) injection with STZ is used to mimic the pathology of human sporadic AD [5]. However, a major disadvantage of this method is the invasiveness of the ICV injection, which involves craniotomy and directly damages the brain tissue. A previous paper confirmed accurate and reproducible access to the artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) of rodents using a cisterna magna (CM) injection method [6]. Furthermore, the injected molecules diffused into the parenchyma, similar to diffusion following ICV injection [7].

In the present study, we produced a rodent model of AD, using STZ injection via the CM and determined the development of AD-like pathologies. It was found that this model successfully induced AD-like pathological features, such as extracellular Aβ accumulation and synaptic loss.

Materials and methods

Experimental animals

Male Sprague Dawley rats (460 ± 20 g, 14 weeks old) were housed in a temperature-controlled room (20–23 °C) with 30–60% humidity in a 12-h light-dark cycle with ad libitum access to standard food pellets and water. All procedures were approved by the Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Approval No. KRIBB-AEC-18016).

CM injection of STZ and brain sampling

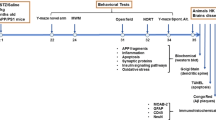

For CM injection of STZ, we used a needle-tubing assembly that comprised of PE10 and PE50 tube tubing, 27G dental needle, PE10/PE50 tubing connector and 22G Hamilton syringe (Fig. 1b) The rats were anesthetized with 3% isoflurane in an induction chamber and maintained under isoflurane anesthesia at 2% during injection. STZ (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in aCSF and was infused into the CM at a rate of 10 μl / min (10 μl total volume, final dose 3 mg/kg). The needle was maintained in place for 1 min after injection. Rats received injections once every week for 4 weeks, before being sacrificed for analysis at acute (4 weeks) and chronic (16 weeks) time points (Fig. 1a). For tissue sampling, rats were anesthetized with 30% urethane and transcardially perfused with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The brain was dissected, and the hemisphere was used for immunohistochemistry and western blot analysis, respectively.

Experimental design and cisterna puncture method. a A schematic timeline showing CM-STZ injections and subsequent sampling points. b The needle tubing assembly for CM injections. A 27G dental needle was connected with polyethylene tubes and the terminal of the tube was linked to 22G Hamilton syringe. c-d The method used for CM injections

General health monitoring

Body weight was recorded weekly prior to injections. Blood glucose levels were measured using Accu-Chek® Guide meter (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) on the 4 and 16 weeks after the first STZ injection.

Immunohistochemistry

The hemisphere was fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 2 days at 4 °C. After dehydrating with 30% sucrose, the tissues were embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound, and transverse sections (30 μm) were serially cut using a cryostat. The sections were then placed in 88–91% formic acid for antigen retrieval of Aβ. After blocking using 4% normal horse serum for 2 h, sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C in diluted primary antibody for Aβ (6E10; Novus, Plainsboro, NJ, USA) and PSD95 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA). Sections were then incubated with biotinylated anti rabbit-IgG secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). The sections were stained with DAB (3,3′-Diaminobenzidine; Vector Laboratories).

Western blot analysis

The hippocampus was harvested from the hemisphere and homogenized in RIPA buffer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Proteins lysates were loaded onto 10–16% SDS-PAGE gels, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and blocked with blocking buffer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Membranes were incubated at 4 °C overnight with primary antibodies against PSD95 (Abcam) and β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich). Following washing with TBST (tris-buffered saline with 0.1% tween 20), the membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. Specific binding was detected using a chemiluminescence detection system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

The data represent the mean and standard deviation (SD) from three independent experiments (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) conducted by GraphPad Prism 5 software (San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

Change in body weight and blood glucose by CM-STZ

Body weight was reduced in the STZ-injected group when compared to the aCSF-injected group until 4 weeks. However, after the final injection, body weight appeared to recover, with no significant difference between the STZ-injected group and control animals by 8 weeks (Fig. 2a). To analyze the effect of STZ on metabolism, we measured blood glucose level at random or in a fasting state at week 4 and 16. There was no significant alteration in the average blood glucose level between aCSF- and STZ-injected groups (Fig. 2b and c).

CM-STZ induced extracellular Aβ accumulation and synaptic loss

To confirm the presence of Aβ accumulation in CM-STZ model, we performed immunochemistry using an Aβ (6E10) antibody in CA3 of the hippocampus. Aβ accumulation was observed outside of the cells and was increased in the STZ-injected group at 16 weeks (Fig. 3). In addition, we analyzed the expression of the post-synaptic protein PSD95 by western blotting and immunohistochemistry. Although expression levels of PSD95 in the hippocampus were not altered at 4 weeks in the STZ-injected group, a significant decrease was observed at 16 weeks when compared to controls (Fig. 4a and b). Moreover, the morphology of synapse was abnormal in STZ-injected group (Fig. 4c). These results suggest that AD-like pathologies were induced by CM-STZ injection.

Extracellular Aβ in the hippocampal CA3. Representative sections showing Aβ (6E10) expression (brown) in area CA3 of the hippocampus from aCSF-injected (left; a-c) and STZ-injected (right; d-f) animals. Counterstaining with hematoxylin can be seen in blue. Scale bars = 50 μm. The lower panels show high-magnified images of the regions indicated by white square in the upper panels, respectively

STZ-induced alteration of neuronal synapses in the hippocampal CA1. a-b Expression of PSD95 protein were analyzed by western blots using brain tissue from aCSF- and STZ-injected animals. c Representative sections showing PSD95 expression in CA1 of the hippocampus from CSF-injected (left) and STZ-injected (right) animals. The lower panels show high-magnified images of the regions indicated by white square in the upper panels. Scale bar = 100 μm. The data are presented as mean values ± SD (n = 3). * denotes p < 0.05

Discussion

A common model of sporadic AD involves a ICV-STZ injection [8]. However, ICV injection is an invasive procedure involving skin incision and trauma to brain tissue, which can bring the reliability of results into question. Therefore, we proposed that CM injection would be equally effective at inducing AD and overcome some limitations of the ICV model. The current study provides evidence that using the CM as an alternative site of STZ injection is indeed effective at producing key pathological features of sporadic AD in a less invasive manner.

One key pathological finding was the increase in extracellular Aβ and synaptic loss in the CM-STZ model. A previous study has shown that intracellular Aβ accumulation is increased 3 months after ICV-STZ injection, and that Aβ plaques are detectable at 6 months [9]. We did not see plaques in our CM-STZ model, however our study only extended to 4 months post-STZ injection and we did observe an increase in extracellular Aβ at this time point.

Furthermore, PSD95 was reduced in the hippocampus by CM-STZ injection after 16 weeks, but not at 4 weeks. Decreases in the expression of post synaptic protein PSD95 are associated with a decline in learning and memory function [10], so this corresponds to pathological changes associated with the development of AD in our model.

Loss of body weight is a common characteristic in AD patients and ICV-STZ rodents have also been shown to lose weight without experiencing any change in blood glucose [11]. In our study, CM-STZ caused weight loss during the injection period, which recovered to control levels following the last injection, with no alteration in blood glucose.

An additional benefit of CM-STZ injection model is the ability to administer many injections over time, due to the reduced invasiveness of the procedure. In our case, we were able to repeatedly inject STZ into aCSF for 4 weeks. This approach mitigated the effects of STZ clearance during aCSF turnover.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that our CM-STZ injection method is less-invasive and induces a similar sporadic AD-like pathology to the ICV-STZ injection model.

Conclusions

We suggest that the method for producing a sporadic AD-like rodent model using less-invasive STZ injection via the CM.

Availability of data and materials

All data produced or analyzed in the present study are available upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- aCSF:

-

Artificial cerebrospinal fluid

- AD:

-

Alzheimer’s disease

- Aβ:

-

Amyloid-beta

- CM:

-

Cisterna magna

- ICV:

-

Intracerebroventricular

- DAB:

-

3,3′-Diaminobenzidine

- SDS-PAGE:

-

Sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- RIPA buffer:

-

Radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer

- STZ:

-

Streptozotocin

- TBST:

-

Tris buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20

References

Xie A, Gao J, Xu L, Meng D. Shared mechanisms of neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:648740.

Pinheiro L, Faustino C. Therapeutic strategies targeting amyloid-beta in Alzheimer's disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2019;16(5):418–52.

Shineman DW, Basi GS, Bizon JL, Colton CA, Greenberg BD, Hollister BA, Lincecum J, Leblanc GG, Lee LB, Luo F, et al. Accelerating drug discovery for Alzheimer's disease: best practices for preclinical animal studies. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2011;3(5):28.

Correia SC, Santos RX, Perry G, Zhu X, Moreira PI, Smith MA. Insulin-resistant brain state: the culprit in sporadic Alzheimer's disease? Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10(2):264–73.

Kamat PK. Streptozotocin induced Alzheimer's disease like changes and the underlying neural degeneration and regeneration mechanism. Neural Regen Res. 2015;10(7):1050–2.

Chen Y, Imai H, Ito A, Saito N. Novel modified method for injection into the cerebrospinal fluid via the cerebellomedullary cistern in mice. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars). 2013;73(2):304–11.

Proescholdt MG, Hutto B, Brady LS, Herkenham M. Studies of cerebrospinal fluid flow and penetration into brain following lateral ventricle and cisterna magna injections of the tracer [14C]inulin in rat. Neuroscience. 2000;95(2):577–92.

Grieb P. Intracerebroventricular Streptozotocin injections as a model of Alzheimer's disease: in search of a relevant mechanism. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53(3):1741–52.

Knezovic A, Osmanovic-Barilar J, Curlin M, Hof PR, Simic G, Riederer P, Salkovic-Petrisic M. Staging of cognitive deficits and neuropathological and ultrastructural changes in streptozotocin-induced rat model of Alzheimer's disease. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2015;122(4):577–92.

Sultana R, Banks WA, Butterfield DA. Decreased levels of PSD95 and two associated proteins and increased levels of BCl2 and caspase 3 in hippocampus from subjects with amnestic mild cognitive impairment: insights into their potential roles for loss of synapses and memory, accumulation of Abeta, and neurodegeneration in a prodromal stage of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci Res. 2010;88(3):469–77.

Zhang Y, Ding R, Wang S, Ren Z, Xu L, Zhang X, Zhao J, Ding Y, Wu Y, Gong Y. Effect of intraperitoneal or intracerebroventricular injection of streptozotocin on learning and memory in mice. Exp Ther Med. 2018;16(3):2375–80.

Acknowledgements

N/A.

Funding

This research was supported by the Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology Research Initiative Program (KGM4621922).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YA, JS, and JP participated in design of the experiments, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. JW, H-GY, KK, and C-YJ performed and supported the experiments. J-WH, S-RL, D-SL, and YL edited and revised manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahn, Y., Seo, J., Park, J. et al. Synaptic loss and amyloid beta alterations in the rodent hippocampus induced by streptozotocin injection into the cisterna magna. Lab Anim Res 36, 17 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42826-020-00049-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42826-020-00049-x