Abstract

Irregular fine protrusions formed on the surface of a mechanical part through biomimetic technology can enhance the part’s properties, including tribology, self-cleaning, and light absorption. However, underlying principles for the formation of fine protrusions according to the requirements of their shapes, sizes, and material distributions have not been studied sufficiently. This paper presents the software development for modeling irregular fine protrusions, which is essential for the simulation, experimentation, and analysis of fine protrusions formed by sputter etching.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Biomimetics has resulted in new technologies inspired by biological solutions at the macro- and nano-scales found in nature, such as self-healing abilities, environmental exposure tolerance and resistance, hydrophobicity, self-assembly, and solar energy utilization [1]. An interesting example is the “lotus effect,” [2] as shown in Fig. 1. This refers to self-cleaning properties arising from ultrahydrophobicity, as exhibited by the leaves of nelumbo or lotus. Dirt particles are gathered by water droplets owing to the fine protrusions on the lotus leaf, as shown in Fig. 2, which minimizes droplet adhesion to the leaf. Superhydrophobicity has been adopted in many industrial products to prevent the drenching of cloth, paint, or concrete, as well as to deter the accumulation of rain, snow, ice, contamination, or corrosion.

Water on the surface of a lotus leaf [2]

Computer graphics of a lotus leaf surface [2]

Fine protrusions on a part can be fabricated using various methods, including [3]: (1) plasma etching using a mask prepared by lithography, depositing seed materials on a substrate, or direct sputter etching without using masks; (2) chemical vapor deposition to form carbon nanotubes; (3) embedding polymers into pores of anodic alumina as a template, followed by extruding it to form nanofibers, which are then plated to form silver nanowires and gold nanorods; (4) forming nanostructures through plating and electrochemical reaction; (5) coating of nanoparticles. However, complex processes are adopted in all these methods, which is not cost effective. Moreover, in some cases the strength and heat resistance of the protrusions are insufficient for industrial applications.

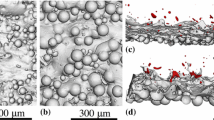

The authors discovered that fine cone-shaped protrusions can be formed on surfaces of stainless steels, low alloyed steels, or tool steels through argon ion sputter etching [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11], a simpler and more cost effective process comparing with the above- mentioned methods. Figure 3 shows the formulation process of conical protrusions through argon ion sputter etching. The origin of the protrusion is a carbide formed on the surface. It grows to a certain size when sputter etching accelerates the diffusion of carbide-forming elements, Cr and C, from the interior of the specimen to the surface. As shown in Fig. 4, the sizes of the protrusions formed varied from 0.1 to 5 μm in diameter or width and the height/diameter ratio exceeded 1.5.

The protrusions exhibited excellent mechanical properties with only a small decrease in pitting corrosion resistance. They can be used as dies to form fine holes on a polymer film to reduce light reflections. Furthermore, they can enhance the adhesion of printing ink on a paper or cloth and improve the bonding between a transportation roll and the paper and cloth that it carries. Further, the large surface area of protrusions can be utilized as catalysts or supports of catalytic species, and the sharp tips of the protrusions can be utilized for the design of a cold emitter, temperature sensor, or heat sink of a micromachine.

However, the underlying principles for the formation of fine protrusions of various shapes, sizes, and distributions have not been studied sufficiently. Hence, we conducted a study to investigate the tribological properties of irregular fine protrusions. The steps performed in the study are shown in Fig. 5. First, the irregular fine protrusions were formed on the surface of several specimens (metals and alloys) through sputter etching using argon or xenon plasma. Next, geometry models of the fine protrusions were created, and the tribological properties of the specimen when lubricant oil was applied on it were simulated and analyzed using the moving particle semi-implicit method (MPS) [12] with support from the ParticleWorks software package. The simulation and analysis results were then compared with the results obtained from the tribological experiments on the specimen. The comparison result was then used to modify the MPS model. This paper presents the software development for modeling irregular fine protrusions, an essential component of the study.

Methods

In this study, the geometric models of fine protrusions, in the form of a Hermite bicubic surface patch (Sij at the i-th row and j-th column) derived from horizontal squares, are mathematically described by the following Hermite Eq. (1) of two parameters u, v (0 ≤ u ≤ 1, 0 ≤ v ≤ 1) [13, 14]. As shown in Fig. 6, a curved

Parameters of a Hermite bicubic surface patch [13]

surface patch is defined by 16 boundary conditions, including the four corner position vertexes (Qij, Qi(j+1), Q(i+1)j, Q(i+1)(j+1)), eight tangent vectors (\( {\dot{Q}}_{ij}^v \), \( {\dot{Q}}_{i\;\left(j+1\right)}^v \), \( {\dot{Q}}_{\left(i+1\right)j}^v \), \( {\dot{Q}}_{\left(i+1\right)\left(j+1\right)}^v \), \( {\dot{Q}}_{ij}^u \), \( {\dot{Q}}_{i\;\left(j+1\right)}^u \), \( {\dot{Q}}_{\left(i+1\right)j}^u \), \( {\dot{Q}}_{\left(i+1\right)\left(j+1\right)}^u \)) at the corner points (two at each point in the u and v directions), and four twist vectors (\( {\ddot{Q}}_{ij}^{uv} \), \( {\ddot{Q}}_{i\;\left(j+1\right)}^{uv} \), \( {\ddot{Q}}_{\left(i+1\right)j}^{uv} \), \( {\ddot{Q}}_{\left(i+1\right)\left(j+1\right)}^{uv} \)) at the corner points. The tangent vector at a corner point can be approximated by the direction and length of chord lines joining the neighboring corner points. Hence, the tangent vector information need not be input, and the calculation of the surface parameters is simplified. The software was developed with Visual C++ [15] and OpenGL [16, 17].

Results

Figure 7 shows the user interface of the developed software. Tables 1 and 2 show the menu and toolbar.

Input and check boxes

The input and check boxes at the bottom of Fig. 7 are illustrated in the same figure.

Implementation

The software was implemented in the following steps. First, horizontal squares were defined (Fig. 8). Next, each vertex was raised to a height to create four patches around it by computing their coordinates according to Eq. (1) to create a protrusion, and the tangent vector was shortened/extended/rotated to change the shapes of the patches with both position and tangent continuities (Fig. 9). Multiple vertexes can be raised to form protrusions with random heights effectively (Figs. 10 and 11). Furthermore, multiple vertexes can be raised to create protrusions with different heights according to the law of weights (Figs. 12 and 13). These operations were performed using a computer mouse. A test model of the cone-shaped protrusions is shown in Fig. 14. After discretizing the protrusion surfaces according to Eq. (1), the discretized points were converted into a triangular-faced mesh to create a stereolithograph (STL) file.

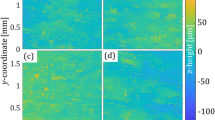

This software package has been used to develop a computer simulation program for the design of a nonslip and nondestructive medical plier. As shown in Fig. 15, the working surface of the plier comprises two convex sections, in which one was produced by a high-precision machine tool in millimeters and the other was generated by sputter etching in nanometers. The second section is small and can increase friction force without damaging human body tissues. Figure 16 shows the computational simulation using the MPS software package ParticleWorks. The pressure and friction force distribution between the plier and object to be held can be observed and used to strategically assist the shape design of the two sections of the plier.

Conclusions

A software for modeling irregular fine protrusions was developed to simulate and analyze the properties of fine protrusions formed by sputter etching. A Hermite bicubic surface was adopted in this software, although other representations such as the Bezier and B-spline surfaces can be used for free-form surfaces, and fractals can be used for some natural shapes. This was because each Hermite bicubic patch was defined with geometric conditions of four vertexes, which rendered it easy to describe local variations of a shape. By contrast, each Bezier surface or B-spline surface was defined with 16 vertexes, which was suitable for defining large smooth surfaces but not ideal for modeling irregular fine protrusions. Because the statistical character of each fine protrusion differed from that of the entire surface, fractals were not applicable.

Using this software, fine protrusions in various shapes, such as cone, ring, sphere, and pipe can be created. The maximum number of modeled fine protrusions was approximately 106, which was sufficient for the MPS analysis and simulation. A protrusion can be created rapidly by clicking on a computer mouse. Large-scale of protrusions can be created effectively with the random height method. The STL data of the created protrusions can be input to and processed by the MPS software package ParticleWorks. Furthermore, the software developed is applicable to geographic information systems. Its open structure allows the functions to be enhanced to improve the efficiency and accuracy of modelling.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- MPS:

-

Moving particle semi-implicit

- STL:

-

Stereolithograph

References

Biomimetics. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biomimetics. Accessed 1 Jun 2019

Lotus effect. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lotus_effect. Accessed 1 Jun 2016

Wang R, Nakasa K, Kubo T, Yamamoto A, Kaneko J (2015) Enhancement of visible light ab-sorbance and hydrophobicity by sputter-coating of PTFE onto fine protrusions formed by sputter-etching of steels. Mater Trans 56(1):91–98. https://doi.org/10.2320/matertrans. M2014270

Wang RG, Zhang QL, Kato M, Nakasa K (2006) Formation of fine and dense conical carbides on tool steel surface by sputter-etching. Mater Trans 47(7):1798–1804 https://doi.org/10.2320/matertrans.47.1798

Nakasa K, Yan X (2008) Deformation behavior of surface layer with conical and ring-shaped protrusions formed by sputter-etching of SUS304 stainless steel. Jpn J Inst Met 72(8):610–616 https://doi.org/10.2320/jinstmet.72.610

Nakasa K, Yamamoto A, Kawata T, Wang RG (2009) Deformation and delamination behavior of sputter-deposited film on the conical protrusions formed by sputter-etching of stainless steel wire. Surf Coat Technol 204(1–2):108–114 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2009.06.046

Nakasa K, Yan X, Yoshida M, Sumomogi T (2010) Deformation characteristics of fine protru-sions formed by sputter-etching of stainless steels. J Solid Mech Mater Eng 4(7):1103–1110 https://doi.org/10.1299/jmmp.4.1103

Nakasa K, Wang RG, Yamamoto A, Sumomogi T (2012) Formation of fine protrusions on steel sheets and wires by sputter etching. Tetsu-to-Hagane 98(12):658–666 https://doi.org/10.2355/tetsutohagane.98.658

Nakasa K, Yamamoto A, Wang R, Sumomogi T (2014) Formation of fine protrusions by sputter etching of martensitic stainless steels. Tetsu-to-Hagane 100(5):647–655 https://doi.org/10.2355/tetsutohagane.100.647

Nakasa K, Yamamoto A, Wang RG, Sumomogi T (2015) Effect of plasma nitriding on the strength of fine protrusions formed by sputter etching of AISI type 420 stainless steel. Surf Coat Technol 272:298–308 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2015.03.048

Nakasa K, Gao SD, Yamamoto A, Sumomogi T (2019) Plasma nitriding of cone-shaped pro-trusions formed by sputter etching of AISI 420 stainless steel and their application to impres-Sion punch to form micro-holes on polymer sheets. Surf Coat Technol 358:891–899 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2018.12.027

Moving particle semi-implicit method. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moving_particle_semi-implicit_method. Accessed 1 Jun 2019

Hughes JF, van Dam A, McGuire M, Sklar DF, Foley JD, Feiner SK et al (2012) Computer graphics: principles and practice, 3rd edn. Addison -Wesley Publishing Company, New Jersey

Watt A (2000) 3D computer graphics, 3rd edn. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, New York

Schildt H (1997) Teach yourself C++, 3rd edn. McGraw-Hill Companies, New York

Woo M, Neider J, Davis T, Architecture O, Board R (1997) OpenGL programming guide: the official guide to learning OpenGL, version 1.1, 2nd edn. Addison-Wesley publishing company, New Jersey

Ezzell B (1996) 32-bit windows programming. Sams Publishing Company, Hoboken

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Prometech Software Inc. (https://www.prometech.co.jp/index.html) for providing this research with the MPS software package ParticleWorks.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

None of the authors have any competing interests in the manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, S., Nakasa, K. & Huang, L. Software development for modeling irregular fine protrusions formed by sputter etching. Vis. Comput. Ind. Biomed. Art 3, 11 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42492-020-00047-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42492-020-00047-9