Abstract

Background

Cotton somatic embryogenesis is difficult or rarely frequent to present, which has limited gene function identification and biotechnological utility. Here, we employed a rice key somatic embryogenesis-related gene, rice lesion simulating disease 1-like gene (OsLOL1), to develop transgenic cotton callus for evaluating its function in ectopic plants.

Results

Overexpressing OsLOL1 can promote cotton callus to form embryogenic callus, not only shortening time but also increasing transition of somatic callus cells to embryogenic callus cells. And the regenerating plantlets per transgenic OsLOL1 embryogenic callus were significantly higher than those in the control transformed with empty vector. Analysis of physiological and biochemical showed that OsLOL1 can repress cotton superoxide dismutase 1 gene (GhSOD1) expression, possibly resulting in reactive oxidant species (ROS) accumulation in transgenic callus cells. And OsLOL1-overexpressed embryogenic callus exhibited higher α-amylase activity compared with the control, resulting from the promotion of OsLOL1 to cotton amylase 7 gene (GhAmy7) and GhAmy8 expression.

Conclusion

The data showed that OsLOL1 could be used as a candidate gene to transform cotton to increase its somatic embryogenesis capacity, facilitating gene function analysis and molecular breeding in cotton.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Plant somatic embryogenesis is a key process of cell totipotency and is an important type of plant regeneration as well as organogenesis plant regeneration. Cotton somatic embryogenesis generally depends on the genotypes of varieties. Currently, quite a few varieties can take place somatic embryogenesis (Cao et al. 2019; Kumria et al. 2003; Mishra et al. 2003; Sun et al. 2006; Wu et al. 2004; Xiao et al. 2018). Additionally, cotton somatic embryogenesis and plant regeneration are time- and labor-consumed process, because it takes a long time to transform somatic callus cells into embryogenic callus cells (somatic-to-embryogenic callus cells) with quite low transition rates (Li et al. 2019). Cotton somatic embryogenesis is a key process in plant regeneration and genetic transformation, which contributes to cotton gene function identification and molecular breeding. However, cotton somatic embryogenesis and plant regeneration are affected by genotypes and environmental factors, of which cotton genotype is a main effector to determine cell fate from somatic callus cells to embryogenic callus cells. The transition of somatic-to-embryogenic cells may be determined by a set of genes’ combination or quite a few genes in plants (Cao et al. 2019; Wu et al. 2004; Xiao et al. 2018). Currently, the increasing researches showed that some key genes regulate plant somatic embryogenesis and plant regeneration (Borderies et al. 2004; Geshi et al. 2013; Ledwoń and Gaj 2011; Long et al. 2018; Nowak et al. 2015; Pérez-Pérez et al. 2019; Poon et al. 2012; Solís et al. 2016; Stone et al. 2008; Uddenberg et al. 2016; Wang et al. 2005; Zheng et al. 2013). For example, AGAMOUS-Like15 promotes somatic embryogenesis in Arabidopsis and soybean (Zheng et al. 2013). LEAFY COTYLEDON1, FUSCA3 regulate somatic embryogenesis induction in Arabidopsis under auxin treatment (Ledwoń and Gaj 2011). PaHAP3A overexpression can promote ectopic embryo differentiation from maturing somatic embryos of Norway spruce (Uddenberg et al. 2016). Arabidopsis ERF022 induces somatic embryogenesis associated with the ethylene-related pathway (Nowak et al. 2015). Arabinogalactan proteins (AGPs) stimulate somatic embryo development in maize (Borderies et al. 2004), Arabidopsis (Geshi et al. 2013), cotton (Poon et al. 2012), and Quercus suber (Pérez-Pérez et al. 2019). Rice lesion simulating disease (OsLSD1) protein, also named as OsLSD1-like, promotes somatic embryogenesis and plant regeneration (Wang et al. 2005). Recent report showed that miR156-SPL modules regulate induction of somatic embryogenesis in citrus callus (Long et al. 2018). However, the few key genes or proteins have been identified in cotton somatic embryogenesis. Thereby, we investigated whether the somatic embryogenesis-related from other plants can promote transition of cotton somatic-to-embryogenic callus cells.

These key embryogenic genes could regulate the expression of downstream genes to change physiological and biochemical stats of callus cells, facilitating in transition of somatic-to-embryogenic callus cells. These reports indicated that somatic callus cells under abiotic stresses could be easier to transform into embryogenic callus cells (Castander-Olarieta et al. 2019; Mohanapriya et al. 2019). Abiotic stresses usually bring high reactive oxidant species (ROS) accumulation in callus cells, reasoning from expressing repression of antioxidant enzyme genes, such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), peroxidase (POD), and so on (Fehér 2015; Ikeda-Iwai et al. 2003; Pasternak et al. 2002). Recently, starch content in cells was found to determine transition of somatic-to-embryogenic callus cells (Long et al. 2018). The callus cells with high starch levels could develop embryogenic callus cells, but others with low starch levels could not. These researches showed that different physiological and biochemical status in callus cells determined whether these cells could form embryogenic callus cells.

Previous researches showed that OsLOL1 can promote rice somatic embryogenesis and plant regeneration (Wang et al. 2005). Further study of OsLOL1 found that it repressed OsSOD1 expression and attenuated SOD activity in rice, leading to ROS accumulation (Wu et al. 2014). In Arabidopsis, LSD1, a homolog of LOL1, performs antagonist function with LOL1 in regulating ROS homeostasis in cells (Dietrich et al. 1994). Interestingly, OsLOL1 could promote rice amylase 7 gene (OsAmy7) and OsAmy8 expression, accelerating starch degradation for energy supplying. Thereby, we employed OsLOL1 as a candidate gene to transform cotton for increasing its embryogenic callus formation capacity.

In this study, we introduced OsLOL1 gene in Gossypium hirsutum cv. Jihe 713 callus cells. The transformed calli were detected by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis, and expression levels were examined by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis. The results showed that overexpressed-OsLOL1 callus cells possessed higher capacity in transition of somatic-to- embryogenic callus cells and plant regeneration compared with the control callus cells transformed with empty vector. Overexpressed-OsLOL1 conferred cotton callus cell increasing embryogenic capacity mainly due to ROS accumulation and acceleration of energy supplying.

Results

Overexpressing OsLOL1 increases cotton somatic embryogenesis

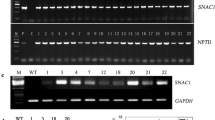

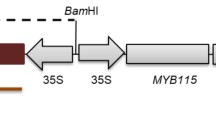

Rice LOL1 has been reported to promote somatic embryogenesis and plant regeneration (Wang et al. 2005; Wu et al. 2014). To increase cotton somatic embryogenesis and plant regeneration, we introduced OsLOL1 gene into the cotton chromosomes through Agrobacterium-mediated transformation method. The 35S:OsLOL1 vector was transformed into the cotton hypocotyl fragments as explants. The putative transgenic plantlets with overexpressing OsLOL1 were generated through callus induction, embryogenic callus formation, somatic embryo emergence and plantlet regeneration. And empty vector was transformed into the explants as the control. About 84.0% calli transformed with 35S:OsLOL1 vector were positive by PCR detection with OsLOL1 gene as well as positive amplification of NPT II gene (Fig. 1a), and the 88.5% control calli were confirmed positive transformants with NPT II gene. As shown in Table 1, the number of embryogenic callus with OsLOL1 was extremely significantly higher than the control at 90 d after transformation, 0.91 vs 0.39 per explant, indicating that OsLOL1 can promote somatic cell embryogenesis. And embryogenic callus with OsLOL1 can produce much more regenerating plantlets than the control, 11.8 vs 3.6 per embryogenic callus, which showed that OsLOL1 extremely significantly increase plant regeneration rates compared with the control. Moreover, the callus cells with overexpressing OsLOL1 extremely significantly shortened the time of somatic-to-embryogenesis callus by about 21 d compared with the control (Fig. 1b). Together, overexpressing OsLOL1 can promote cotton callus embryogenesis and plant regeneration. Additionally, according to qRT-PCR analysis (Fig. 1c and d), at least 10 transformed calli with higher expression level of OsLOL1 or npt II were selected to subject to gene expression analysis and physiological and biochemical assay.

Development of transgenic cotton embryogenic calli with OsLOL1 overexpression and empty vector. a PCR detection of transgenic cotton embryogenic calli. M: DNA marker; P: positive control, the plasmid with OsLOL1 gene; N: non-transgenic cotton plants; 1–18: various independent embryogenic calli. b Days of transition from somatic callus to embryogenic callus. NP: samples with empty vector, OE: those with OsLOL1. Bar values (SD) are calculated through three biological repeats. Double asterisks represent extremely significant differences (P < 0.01) by Student’s t-test. c and d Relative expression levels of OsLOL1 (c) and NPT II (d). OE1–10: those with OsLOL1 overexpression, NP1–10: the embryogenic calli with empty vector. GhUbi gene was used as internal control for normalization. The expression levels of OE1 and NP1 are arbitrarily regarded as “1”, respectively. Bars represent SD from biological repeats

Overexpressing OsLOL1 repressed GhSOD1 expression

We found lots of transgenic callus cells death around the embryogenic cell granular or somatic embryos although the transgenic OsLOL1 calli can form much more embryogenic calli and somatic embryos, indicating that OsLOL1 promotes cell death (Fig. 2a). Previous research showed that knockdown of OsLOL1 promoted OsSOD1 expression and attenuated ROS accumulation (Wu et al. 2014). To investigate whether OsLOL1 overexpression repressed cotton SOD1 (JX138573.1) expression, we conducted qRT-PCR analysis. The result showed that GhSOD1 expression level in the overexpressing OsLOL1 calli was significantly lower compared with the control (Fig. 2b). Consistent with GhSOD1 expression level, the SOD enzyme activity of OsLOL1-overexpressed calli was extremely significantly lower than that of the control (Fig. 2c). To further measure SOD enzyme activity, we conducted gel nictro-staining assay. The staining intensity of bands loaded with overexpressing OsLOL1 callus protein was obviously weaker compared with the control, consistent with quantified results (Fig. 2d). The data showed that overexpressing OsLOL1 repressed GhSOD1 expression and decreased SOD enzyme activity, possibly leading to ROS accumulation in cells. To investigate whether ROS was accumulated in overexpressing OsLOL1 calli, the callus tissues were stained with nitrogen blue tetrazole (NBT). The results showed that the colors of the OE calli were darker than that of the control (Fig. 2e), indicating that more ROS in OE calli was accumulated compared with the control. The results suggested that ROS accumulation by OsLOL1 overexpression promotes cotton somatic cell embryogenesis, leading to increase of regenerating plantlets.

OsLOL1 overexpression represses GhSOD1 expression and activity. a Cell death around embryogenic callus or somatic embryos. Arrows point to the dead cell masses. NP: Calli transformed by empty vector, OE: Calli with OsLOL1 overexpression. b Relative expression level of GhSOD1 in embryogenic calli with empty vector or OsLOL1 gene. GhUbi gene was used as internal control for normalization. The expression levels of OE1 and NP1 are arbitrarily regarded as “1”, respectively. c SOD activity of embryogenic calli with empty vector or OsLOL1 gene. d SOD activity by staining analysis in gel in embryogenic calli with empty vector or OsLOL1 gene. e ROS accumulation of cotton calli by NBT staining analysis. In (d) and (e), NP1 is a represent of the embryogenic calli with empty vector. OE1–3 are representatives of the embryogenic calli with OsLOL1 overexpression. Bar represents SD from three biological repeats in (b) and (c). An asterisk or double asterisks show significant (P < 0.05) or extremely significant (P < 0.01) differences of OEs compared with NP1 by Student’s t-test in (c) and (d)

Overexpressing OsLOL1 increased GhAMY7 and GhAmy8 expression

Previous report showed that OsLOL1 can promote OsAmy7 and OsAmy8 expression to accelerate starch degradation, contributing to seed germination (Wu et al. 2014). To investigate whether overexpressing OsLOL1 in cotton calli increased cotton Amy7 (Ghir_A05G020740.1) and Amy8 (Ghir_D01G011780.1) expression, we conducted qRT-PCR analysis. The results showed that GhAmy7 and GhAmy8 expression levels in transgenic OsLOL1 calli were significantly higher by 5 folds compared with the control (Fig. 3a). The α-amylase activity in OsLOL1-overexpressed calli was also significantly higher by 2 folds compared with the control (Fig. 3b). Interestingly, when we measured the starch content, the starch amount in transgenic OsLOL1 calli slightly reduced, but not significantly, compared with the control, indicating that cotton calli possess a high potential capacity of starch synthesis. These data suggested that OsLOL1 can promote GhAmy7 and GhAmy8 expression and increase α-amylase activity, contributing to somatic embryogenesis and plantlet growth.

Overexpressing OsLOL1 promotes GhAmy7 and GhAmy8 expression and α-amylase activity in embryogenic calli. a Relative expression levels of GhAmy7 and GhAmy8 in the embryogenic calli with OsLOL1 or empty vector. Bars represent SD from three biological repeats. b α-amylase activity of the embryogenic calli with OsLOL1 or empty vector. Bar represents SD from three biological repeats. One asterisk or double asterisks show significant (P < 0.05) or extremely significant (P < 0.01) differences of OEs compared with NP1 by Student’s t-test

Discussion

Plant somatic embryogenesis is controlled by single gene or a set of genes (Yang and Zhang 2010). The expression levels of these genes could determine somatic callus cell fate of whether they develop embryogenic callus cells (Yang and Zhang 2010; Rupps et al. 2016). However, cotton somatic embryogenesis highly depends on quite a few genotypes of varieties and is a low rate of transition of somatic-to-embryogenic callus cells (Ge et al. 2015). Here, we introduced a rice somatic embryogenesis-related gene, OsLOL1, into the cotton genome. The results showed that overexpressing OsLOL1 can increase cotton somatic embryogenesis capacity and promote plant regeneration.

The OsLOL1-overexpressed embryogenic callus cells had significantly reduced SOD1 activity associated with ROS accumulation compared with the control, possibly leading to increase of somatic embryogenic capacity. The result suggested that high ROS level facilitates somatic embryogenesis in cotton callus cells. This result is similar to ROS accumulation of callus treated by environmental stresses to promote somatic embryogenesis and plant regeneration (Rai and Shekhawat 2011; Rodríguez-Serrano et al. 2012). All in all, high ROS level in callus promotes transition of somatic-to-embryogenic callus cells and plant regeneration.

In this study, OsLOL1 overexpression promoted cotton Amy7 and Amy8 expression, leading to alpha-amylase activity increase in embryogenic callus cells. High amylase level could accelerate starch degradation, providing enough energy to callus cells during transition of somatic-to-embryogenic callus cells. Recently, the report showed that amyloplast in callus cells is important in cell totipotency to determine transition of somatic-to-embryogenic callus cells (Guo et al. 2019). Together, high energy transition and supplying is important in plant somatic embryogenesis and plant regeneration, especially synthesis and degradation of starch.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and transformation

The G. hirsutum cv. Jihe 713 were used in this article. The coding sequence (CDS) of OsLOL1 (GenBank accession number AY525368) from Oryza sativa cv. Nipponbare was amplified and cloned into the pBin438 vector to be driven by CaMV35S promoter. The 35S:OsLOL1 vector and empty vector were used to transform into Jihe 713 by Agribacterium tumefaciens (strain: LBA4404)-mediated transformation according to previous methods (Wu et al. 2011). The gene cloning primers were listed in Table 2.

DNA extraction

The cotton genomic DNA was isolated and purified from calli by Plant Genome Extraction Kit (TianGen, Beijing, China) according to the instruction manual. The DNA of samples was diluted into 20 ng·μL− 1 for PCR reaction. The PCR primers were listed in Table 2.

qRT-PCR reaction

Total RNA of 100 mg embryogenic calli was extracted using the Plant Total RNA Extraction Kit (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China). One microgram of total RNA was performed the reverse-transcription reaction to synthesis first-strand cDNA using TransScript First-Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (TransGen). These cDNA samples were further diluted by 20-fold to subject to analysis. The qRT-PCR was employed to check related genes expression levels in embryogenic calli. For qRT-PCR analysis, the SYBRGreen Real-Time PCR Master Mix (TsingKe, Beijing, China) was employed on the CFX96 TouchTM Real-Time PCR detection systems (Bio-Rad, Foster City, United States). The GhUbi (Gh_A09G194200.1) gene was used as internal control for normalization. All reactions were performed in three biological repeats with three technical repeats. The primers used are shown in Table 2.

SOD activity assay

Total protein was extracted from 100 mg frozen sample in 300 μL of SOD extraction buffer according to previous reports with minor modification (Van Camp et al. 1994). In brief, the resulting homogenate was centrifuged for 5 min at 18 000 g to obtain crude protein, whose content was quantified using a protein assay kit (Bio-Rad). The SOD activity was measured according to Beauchamp and Fridovich (Beauchamp and Fridovich 1971). The same experiment was repeated three times.

Forty micrograms protein was subjected to load in 12% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and to run at 180 V for 2 h. The gel was stained to determine SOD activity according to the previous methods (Beauchamp and Fridovich 1971; Pan and Yau 1992).

ROS level is monitored by NBT staining in cotton calli according to the operation procedure of the NBT staining kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). In brief, the calli were soaked into the BCIP/NBT solution for 20–40 min under dark condition at 37 °C. The reaction was stopped by H2O, and staining calli were washed with H2O for 2–3 times. Then, the staining calli were treated with anhydrous alcohol for decolorization and coagulation. Finally, the treated calli were observed under the stereomicroscope and photographed.

Assay of α-amylase activity

The harvested samples were grinded into powder using liquid nitrogen, which were homogenized in a cold PBST buffer and centrifuged at 15 000 r min− 1 for 10 min at 4 °C. To inactivate β-amylase activity, the supematants were heated to 60 °C for 30 min and centrifuged again to obtain the supernatants for assay of a-amylase activity according to the method of Grosselindemann and Graebe (1991). Determination of α-amylase activity was measured according to the previous reports (Choi et al. 1996) with minor modification. In brief, the 2% (m/v) starch solution was used for the assay. An aliquot of enzyme solution was added to a 1.5-mL tube with 0.2 mL of starch solution, 0.2 mL of 0.1 mol·L− 1 sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.3) and 0.2 mL of 10 mmol·L− 1 CaC12. The adjusted 1.2 mL total volume solution was reacted at 37 °C for 10 min and was stopped by 0.4 mL of KI/I2 solution. The absorbance was measured at 620 nm.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis is carried out by two-way ANOVA with Student’s t-test, and P < 0.05 and P < 0.01 are considered as significant and extremely significant differences, respectively.

Availability of data and materials

The data and materials for supporting the results of this article are included within the article.

References

Beauchamp C, Fridovich I. Superoxide dismutase: improved assays and an assay applicable to acrylamide gels. Anal Biochem. 1971;44(1):276–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-2697(71)90370-8.

Borderies G, le Bechec M, Rossigno M, et al. Characterization of proteins secreted during maize microspore culture: arabinogalactan proteins (AGPs) stimulate embryo development. Eur J Cell Biol. 2004;83(5):205–12. https://doi.org/10.1078/0171-9335-00378.

Cao A, Shao D, Cui B, et al. Screening the reference genes for quantitative gene expression by RT-qPCR during SE initial dedifferentiation in four Gossypium hirsutum cultivars that have different SE capability. Genes. 2019;10(7):497. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes10070497.

Castander-Olarieta A, Montalbán IA, De Medeiros OE, et al. Effect of thermal stress on tissue ultrastructure and metabolite profiles during initiation of radiata pine somatic embryogenesis. Front Plant Sci. 2019;9:2004. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2018.02004.

Choi YH, Kobayashi M, Sakurai A. Endogenous gibberellin A1 level and α-amylase activity in germinating rice seeds. J Plant Growth Regul. 1996;15(3):147–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00198930.

Dietrich RA, Delaney TP, Uknes SJ, et al. Arabidopsis mutants simulating disease resistance response. Cell. 1994;77(4):565–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-8674(94)90218-6.

Fehér A. Somatic embryogenesis -- stress-induced remodeling of plant cell fate. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1849(4):385–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.07.005.

Ge X, Zhang C, Wang Q, et al. iTRAQ protein profile differential analysis between somatic globular and cotyledonary embryos reveals stress, hormone, and respiration involved in increasing plantlet regeneration of Gossypium hirsutum L. J Proteome Res. 2015;14(1):268–78. https://doi.org/10.1021/pr500688g.

Geshi N, Johansen JN, Dilokpimol A, et al. A galactosyltransferase acting on arabinogalactan protein glycans is essential for embryo development in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2013;76(1):128–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/tpj.12281.

Grosselindemann E, Graebe JE. lStockl D, et al. ent-Kaurene biosynthesis in germinating barley (Hordeum vulgare L., cv. Himalaya) caryopses and its relation to a-amylase production. Plant Physiol. 1991;96(4):1099–104. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.96.4.1099.

Guo H, Guo H, Zhang L, et al. SELTP assembled battery drives totipotency of somatic plant cell. Plant Biotechnol J. 2019;17(7):1188–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.13107.

Ikeda-Iwai M, Umehara M, Satoh S, et al. Stress-induced somatic embryogenesis in vegetative tissues of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2003;34(1):107–14. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01702.x.

Kumria R, Sunnichan VG, Das DK, et al. High-frequency somatic embryo production and maturation into normal plants in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) through metabolic stress. Plant Cell Rep. 2003;21(7):635–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00299-002-0554-9.

Ledwoń A, Gaj MD. LEAFY COTYLEDON1, FUSCA3 expression and auxin treatment in relation to somatic embryogenesis induction in Arabidopsis. Plant Growth Regul. 2011;65(1):157–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10725-011-9585-y.

Li J, Wang M, Li Y, et al. Multi-omics analyses reveal epigenomics basis for cotton somatic embryogenesis through successive regeneration acclimation process. Plant Biotechnol J. 2019;17(2):435–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.12988.

Long JM, Liu CY, Feng MQ, et al. miR156-SPL modules regulate induction of somatic embryogenesis in citrus callus. J Exp Bot. 2018;69(12):2979–93. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/ery132.

Mishra R, Wang HY, Yadav NR, et al. Development of highly regenerable elite Acala cotton (Gossypium hirsutum cv. Maxxa) -- a step towards genotype-independent regeneration. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2003;73(1):21–35.

Mohanapriya G, Bharadwaj R, Noceda C, et al. Alternative oxidase (AOX) senses stress levels to coordinate auxin-induced reprogramming from seed germination to somatic embryogenesis-a role relevant for seed vigor prediction and plant robustness. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:1134. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2019.01134.

Nowak K, Wójcikowska B, Gaj MD. ERF022 impacts the induction of somatic embryogenesis in Arabidopsis through the ethylene-related pathway. Planta. 2015;241(4):967–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-014-2225-9.

Pan SM, Yau YY. Characterization of superoxide dismutase in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 1992;37(1):58–66. https://doi.org/10.6165/tai.1992.37.58.

Pasternak TP, Prinsen E, Ayaydin F, et al. The role of auxin, Ph, and stress in the activation of embryogenic cell division in leaf protoplast-derived cells of alfalfa. Plant Physiol. 2002;129(6):1807–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/pssb.2221890205.

Pérez-Pérez Y, Carneros E, Berenguer E, et al. Pectin de-methylesterification and AGP increase promote cell wall remodeling and are required during somatic embryogenesis of Quercus suber. Front Plant Sci. 2019;9:1915. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2018.01915.

Poon S, Heath RL, Clarke AE. A chimeric arabinogalactan protein promotes somatic embryogenesis in cotton cell culture. Plant Physiol. 2012;160(2):684–95. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.112.203075.

Rai MK, Shekhawat NS. Harish, et al. The role of abscisic acid in plant tissue culture: a review of recent progress. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2011;106(2):179–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11240-011-9923-9.

Rodríguez-Serrano M, Bárány I, Prem D, et al. NO, ROS, and cell death associated with caspase-like activity increase in stress-induced microspore embryogenesis of barley. J Exp Bot. 2012;63(5):2007–24. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/err400.

Rupps A, Raschke J, Rümmler M, et al. Identification of putative homologs of Larix decidua to Babyboom (BBM), leafy cotyledon1 (LEC1), Wuschel-related Homeobox2 (WOX2) and somatic embryogenesis receptor-like kinase (SERK) during somatic embryogenesis. Planta. 2016;243(2):473–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-015-2409-y.

Solís MT, Berenguer E, Risueño MC, et al. BnPME is progressively induced after microspore reprogramming to embryogenesis, correlating with pectin de-esterification and cell differentiation in Brassica napus. BMC Plant Biol. 2016;16(1):176. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-016-0863-8.

Stone SL, Braybrook SA, Paula SL, et al. Arabidopsis LEAFY COTYLEDON2 induces maturation traits and auxin activity: implications for somatic embryogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105(8):3151–6. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0712364105.

Sun Y, Zhang X, Huang C, et al. Somatic embryogenesis and plant regeneration from different wild diploid cotton (Gossypium) species. Plant Cell Rep. 2006;25(4):289–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00299-005-0085-2.

Uddenberg D, Abrahamsson M, von Arnold S. Overexpression of PaHAP3A stimulates differentiation of ectopic embryos from maturing somatic embryos of Norway spruce. Tree Genet Genome. 2016;12(2):18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11295-016-0974-2.

Van Camp W, Willekens H, Bowler C, et al. Elevated levels of superoxide dismutase protect transgenic plants against ozone damage. Nat Biotech. 1994;12(2):165–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt0294-165.

Wang L, Pei Z, Tian Y, et al. OsLSD1, a rice zinc finger protein, regulates programmed cell death and callus differentiation. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2005;18(5):375–84. https://doi.org/10.1094/mpmi-18-0375.

Wu J, Luo X, Zhang X, et al. Development of insect-resistant transgenic cotton with chimeric TVip3A* accumulating in chloroplasts. Transgenic Res. 2011;20(5):963–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11248-011-9483-0.

Wu J, Zhang X, Nie Y, et al. Factors affecting somatic embryogenesis and plant regeneration from a range of recalcitrant genotypes of Chinese cottons (Gossypium hirsutum L.). In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Plant. 2004;40(4):371–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00299-005-0085-2.

Wu J, Zhu C, Pang J, et al. OsLOL1, a C2C2-type zinc finger protein, interacts with OsbZIP58 to promote seed germination through the modulation of gibberellin biosynthesis in Oryza sativa. Plant J. 2014;80(6):1118–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/tpj.12714.

Xiao Y, Chen Y, Ding Y, et al. Effects of GhWUS from upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) on somatic embryogenesis and shoot regeneration. Plant Sci. 2018;270(5):157–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plantsci.2018.02.018.

Yang X, Zhang X. Regulation of somatic embryogenesis in higher plants. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 2010;29(1):36–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352680903436291.

Zheng Q, Zheng Y, Perry SE. AGAMOUS-Like15 promotes somatic embryogenesis in Arabidopsis and soybean in part by the control of ethylene biosynthesis and response. Plant Physiol. 2013;161(4):2113–27. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.113.216275.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and helpful suggestions which help to improve the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of China (31971905 and 31771848) and the State Key Laboratory of Cotton Biology Open Fund (CB2019B02).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wu JH and Luo XL initiated the research and designed the experiments; Wang ZA, Wang P, Xiao JL and Zhang AH performed experiment including genetic transformation and biochemical assays; Hu G and Wang ZA carried out molecular analysis and data statistical analysis. Wu JH wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed in the interpretation of results and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

WANG, Z., WANG, P., HU, G. et al. Overexpressing rice lesion simulating disease 1-like gene (OsLOL1) in Gossypium hirsutum promotes somatic embryogenesis and plant regeneration. J Cotton Res 3, 19 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42397-020-00062-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42397-020-00062-4