Abstract

Background/Aims

Today, the using of diode lasers in dentistry has made a significant progress; it increased the speed of treatment, decreased the time of healing, and showed a bactericidal effect. The thermal effects should be considered in root canal treatment by laser, as the temperature rises to critical levels, causing tissues damage and any thermal change occurs after laser irradiation. The temperature can rise up to 10 °C above the body temperature for less than 2–3 min without damaging the periodontal tissue or burring the tooth structure by using cooling. Antibacterial properties of silver nanoparticles (Ag-NPs) were reducing Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial growth, due to a larger surface to volume ratio of nanoparticles. The goal of this study is to evaluate the bactericidal effect of diode laser irradiation (970 nm), the silver nanoparticles in root canals infected by Enterococcus faecalis bacteria, and the thermal change that occurs after laser application.

Materials and methods

Forty-five extracted single-rooted human maxillary anterior teeth were collected and used as a container for the test. The samples are inoculated by Enterococcus faecalis bacterial strain and randomly divided into three groups: group I (control) (n = 15), group II (Enterococcus faecalis bacteria and silver nanoparticles) (n = 15), and group III (Enterococcus faecalis bacteria and diode laser) (n = 15). The laser group was divided into subgroups according to the time of laser irradiation (20 s, 30 s, and 40 s).

Results

There was a significant difference between the treated groups, in which the laser group showed a high bactericidal effect than the other groups at the time of radiation 40 s, without damaging the tooth structure or periodontal ligament.

Conclusion

Diode laser with proper parameters is used as an adjunctive endodontic disinfection modality due to its antibacterial effect with a temperature tolerated by periodontal tissues with safety limit.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The root canal treatment purpose is to eliminate the bacteria and its by-products and prevents the re-entry of the microorganisms into the root canal system after cleaning the root canal (Estrela et al., 2014). Using mechanical and traditional methods is not enough for cleaning the root canal and dentinal tubular system (Byström & Sundqvist, 1981; Dalton et al., 1998), and excellent cleaning of the dentinal tubules becomes more difficult (Nair et al., 1990); so recently, the dentist used diode laser in the clinic for different dental applications (Mortiz et al., 1998; Pendyala et al., 2017; Yeh et al., 2005).

The diode laser is a semiconductor laser, and its wavelength for dental use ranges between 800 and 1000 nm that emits in a continuous and pulsed mode using an optical fiber as the delivery system (Camargo, 2011). Bacterial reduction and less apical leakage become important to this system and for endodontic treatment. The principal laser action is photo-thermal. The high-power diode laser is used to kill bacteria (El-Batanouny et al., 2008) and stop bacterial growth by thermal effect and closure of the irradiated dentinal tubules (Ashofteh et al., 2014; Kaiwar et al., 2013a).

The laser releases a large amount of energy that is transformed into heat, which is causing damage to the tooth structure, while overheating lead to irreversible changes as melting, microfractures, and carbonization (Alfredo et al., 2008; Gutnecht et al., 2005). The temperature on the outer root surface and apex within 7–8 °C does not cause damage, but if the temperature rises more than 10 °C without cooling, it causes damage in the surrounding periodontal and bony structures (Ribeiro et al., 2007; Hussey et al., 1997).

Nanotechnology has been used in dentistry to provide high mechanical properties and bactericidal effects. These materials as silver nanoparticles have antimicrobial properties and compatible physical properties when compared with conventional materials due to their small size and increased surface area (Rodrigues et al., 2018a; Anil et al., 2017).

Silver nanoparticles (Ag-NP) have a high bactericidal effect, which is widely used in health sciences (Alabdulmohsen & Saad, 2017). Recently, it is used to prevent bacterial growth in different fields and applications, as in dentistry (García-Contreras et al., 2011; Rodrigues et al., 2018b); its antibacterial effect is due to the reduction in particles’ size (Krishnan et al., 2015; González-Luna et al., 2016) and they have self-cleaning properties (Rodriguez-Chang et al., 2016), by effect on Gram (+) and Gram (−) bacteria, producing damage to the microorganism’s membrane (Daming et al., 2014).

Enterococcus faecalis is the most common bacteria leading to failures of root canal treatment (Monawer & Abdulkahar, 2016; Colaco, 2018; Haypek, 2006) resisting the antibacterial agents such as NaOCl in different treatments (Valera et al., 2009; Sohrabi et al., 2016). E. faecalis can form a biofilm and enter inside the dentinal tubules (Duggan & Sedgley, 2007; Rahul et al., 2014), resistance to alkaline pH and to calcium hydroxide pastes, which normally inhibit other bacteria. This resistance may be related to severe and excessive working active proton pump in the membrane of these bacteria (Weckwerth et al., 2013).

This study showed the bactericidal effect by using diode laser (970 nm), and silver nanoparticles on Enterococcus faecalis bacterial strains and changes occur in the tooth structure after laser irradiation.

Material and methods

Sample selection

A total of 45 extracted single-rooted human maxillary anterior teeth were collected and scaled to remove all adhering soft tissues and kept in saline solution (0.09%) before the experiment.

Tooth preparation

The teeth decapitated at the level of cemento-enamel junction (CEJ) using a high-speed diamond disk to facilitate the mechanical preparation of the root canals to be used as a container to perform the test. The working length was established by subtracting 1 mm from the apical foramen. The canals shaped using Gates Glidden drills (Main Inc., Japan) # 4 and # 5, which were used to flare out the coronal part of the canal by maintaining 1 mm of the apical constriction for enough width that will able to contain 25 ml of bacteria and 25 ml of metallic nanoparticles (Ag-NPs). For complete removing of the smear layer, each root canal was irrigated using 17 ml of 17% EDTA (for 2 min) (Oakland Street, Watertown, MA 02272-0780, USA). The teeth were then allowed to air-dry overnight at room temperature, and the apical foramen was sealed externally and waterproofed with two coats of clear nail polish (Kaiwar et al., 2013b). The teeth were placed in the Eppendorf to put them into an autoclave (Melatronic 23, Melag, Berlin, Germany) for 20 min at 121 °C under 1.2 psi pressure for sterility by removing all pre-existing bacteria (Gutkecht et al., 2000; Radaelli et al., 2003). All samples inoculated with Enterococcus faecalis bacterial suspension. The samples were randomly divided into three groups: group I (control) (n = 15), group II (E. faecalis bacteria + Ag-NPs) (n = 15), group III (E. faecalis bacteria + diode laser irradiation) (n = 15). Each group was divided into three subgroups according to the time of diode laser irradiation (970 nm) (20 s, 30 s, and 40 s) (n = 5) at 1 W in continuous mode. The teeth covered by wet sterile cotton of saline to keep the environment during procedure moisture and then placed in a sterile Eppendorf to be ready for the next procedure.

Preparation of media

One liter of culture agar media prepared by using 90 g of BHI agar (Acumedia, Baltimore, Maryland, USA) in 1000 ml distilled water, then heated to the boiling point to dissolve the medium completely. It dispend and sterlized by autoclaving at 15 Ibs pressure (121 °C) for 15 min, and then, it cooled to 50–55 °C and 1 ml of sterile and 1% of potassium telluride solution were added to the medium. It was mixed well and poured into sterile Petri dishes. The solution was allowed to cool down and then maintained in the refrigerator until use to avoid any bacterial contamination.

Bacterial suspension preparation and bacterial inoculation

The bacterial suspension prepared from reference strain of Enterococcus faecalis (ATCC 29212) bacteria, which prepared in BHI agar and then adjusted to 0.5 McFarland units [1.5 × 108 (CFU/mL)]. Twenty-five milliliters of bacterial suspension in BHI broth applied to all samples of root canals using a sterile micropipette with a sterile needle in group I. Twenty-five milliliters of Ag-NPs was added in the root canals of group II. Group III was subjected to laser irradiation treatment at three different times (20 s, 30 s, and 40 s), and the bacterial count was detected after laser irradiation (Hong-gang et al., 2002).

Bacterial count

Enumeration of bacteria was carried out after making serial dilution up till 107 of the inoculums, and from each diluted inoculation, 1 ml of the culture was plated on the surface of BHI agar plates and then incubated aerobically at 37 °C for 24 h. After incubation, enumeration of bacteria was carried out from countable plates (30–300 CFU/ml) (Sieuwerts et al., 2008).

Laser treatment

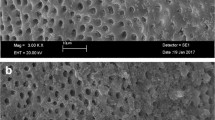

Group III was irradiated using a diode laser (Siro Laser Advance class III b, SIRONA Dental Company, Germany) at wavelength 970 nm and output power at 1 W in a continuous mode. It provided through a flexible 220-ml fiber optic diameter with a special handpiece. The fiber optic was disinfected for each use by 70% ethyl alcohol and inserted inside the cavity with a spiral continuous movement clockwise from the top to the floor and anti-clockwise in a reverse direction (Al-habeeb et al., 2013). This procedure equally distributes the laser energy inside the cavity to avoid excessive heat generation and carbonization in the internal cavity surface. Irradiation time was (20 s, 30 s, and 40 s). A scanning electron microscope (SEM) was used to examine the changes of the tooth structure in each group after laser application (Fig. 1).

Bacteriological evaluation of the treated samples

Colony-forming units (CFUS) were used to detect bacterial count after silver nanoparticle addition as well as laser irradiation. After laser irradiation, 50 ml of suspension solution was placed on a Petri dish and then incubated aerobically in the incubator for 24 h at 37 °C. The grown colonies in all groups were identified and counted (Sieuwerts et al., 2008; Scott, 2011). Upon irradiation, the specimens were placed into sterile Eppendorf tubes and 100 ml of physiological saline solution was added. The extracted fluid was diluted in log 10 steps, and then, 25 ml of each dilution was applied to the culture plates and then incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The colonies were counted and the total number of bacteria (CFUS/ml) was assessed (Colony Star, Funke Gerber Product, Gebr Liebisch, Germany) (Lee et al., 2006; Johnsrud, 2002).

Results

Statistical analysis

The data was presented as mean and standard deviation (SD) values. One-way ANOVA test was used to compare the different treatment modalities as well as the different time periods. Tukey’s test was used for pairwise comparisons between the mean values when ANOVA test is significant. The significance level was set at P ≤ 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed with IBM®Footnote 1 SPSS®Footnote 2 Statistics Version 20 for Windows (Table 1).

The effects of different treatments and different times in each treatment on the bacterial counts are as follows:

A. For the effect of different treatment, there were statistically significant differences between the groups. The laser group showed the statistically significant lowest mean bacterial counts, followed by the silver group. The control group showed the highest mean of bacterial count, and there was no statistically significant difference between times.

B. For the effect of different times within each treatment on the bacterial counts, the laser group showed the statistically significant lowest mean of bacterial counts, and there was also no statistically significant difference between 20 s and 30 s; both showed statistically significant higher mean counts, while 40 s showed the statistically significant lowest mean bacterial count.

In silver nanoparticle group, there was no statistically significant difference between 20 s and 30 s; all showed a highly statistical significant difference on mean bacterial counts, while the 40-s period showed the statistically significantly lowest bacterial count.

The diode laser group showed higher bactericidal effects than the other groups by increasing at the time of laser irradiation. In SEM examination for tooth structure at 40 s, the narrowing in the opening of dentinal tubules occurs without melting or carbonization of the tooth structure.

Discussion

Diode laser avaliable in red and infrared spectrum. Near-infrared (NIR) lasers are characterized by a high absorption of the mineral present in the tooth structure and chromophore present in the soft tissue. In this study, we selected 970 nm wavelengths, which are most commonly used wavelengths in dentistry. However, the body can withstand temperature up to 10 °C of its temperature (37 °C); according to Gutkecht et al. (2000), the tooth structure can tolerate temperature without causing any damage to the root or the adjacent structures, as the effect of diode laser treatment on the tooth structure depends on pulse energy, frequency, spot size, and wavelength. Baburao et al. (2014) in agreement with our, they used continuous mode of radiation, because it is more easy for the dentist to irradiate the whole dentin surface by this way, in which the heat conduction between the periapical tissues and the root canal depended on the thickness of the dentinal walls, while the passage of heat becomes more difficult in the thick wall of the root canal. In our study, the mechanism of the diode laser (970 nm) on dentin, in agreement with Umana et al. (2013), in which a part of the energy absorbed by dentin minerals such as phosphate and carbonate, causing thermo-chemical ablation and occlusion of dentinal tubules. Measuring the rise in temperature during laser irradiation to study the thermal effect on the tooth structure and the periodontal tissues, according to the studies of Anic et al. (1996), in our study, laser irradiation heat increased within the body temperature tolerance without causing any damage to the tooth structure, just a narrowing of the dentinal tubules was observed at delivered output powers of 1 W at 40 s for 970 nm diode laser, which is in agreement with Rosenberg et al. (1971), who reported that the temperature measurements at 810 and 980 nm diode laser irradiation up to 2 W cannot be dangerous to the tooth surface and pulp tissues. Alfredo et al. (2008) demonstated that power out outputs ranging from 0.5 to 2.5 W and irradiation times from 10 to 120 s, the temperature rise in continues mode than the body temperature which is safe for the tooth structure and the surrounding structure which is in agreement with our result that the temperature rise might depend not only on the irradiation mode but also on the tooth anatomy at 40 s because there is no contact between the fiber and dentinal walls. Our results in agreement with Ribeiro et al.’s (2007), who used diode laser with the same parameter and correlated to the lower microleakage due to occlusion of dentinal tubules obtained by Gutnecht et al. (2005).

This study was conducted to evaluate the antibacterial effect of diode laser and silver nanoparticles which have the ability to kill bacteria at different times of exposure for disinfection of contaminated samples as per Gerek et al. (2010). Therefore, our results in laser group III demonstrated that the bacterial counts decreased by increasing the time of laser exposure within few seconds which is in agreement with Ramskold et al. (1997). The findings agreed with this study that, as the time of 40 s of laser exposure, the diode laser could remove the E. faecalis without inducing a high-temperature rise as in Lee et al. (2006). The mechanisms regarding the antibacterial effect of diode laser are that the thermal effect was considered the main reasons for the laser to kill the bacteria (Radaelli et al., 2003). In our study, the cell growth inhibited after exposure to laser irradiation by destruction of the cell wall prevents the cell growth and cell lysis, which is in agreement with Barbosa et al. (2008); also, the thermal effect of the laser causes stress on the cells to prevent the accumulation of protein debris causing cell death (Pimpang et al., 2008; Ahmed et al., 2011).

Ag-NPs have an antibacterial effect against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria as in Rai et al. and do not allow developing resistance (Rai et al., 2012). In silver nanoparticle group II, it showed antibacterial effect which increases by time. It is in agreement with Morones et al. (2005) in which positively charged Ag-NPs interact with the negatively charged bacterial cell walls and adhere and penetrate into the bacterial cell leading to the loss of cell wall and permeability. It showed in our study that Ag-NPs could induce cytotoxicity and inflammatory response in cells resulting from damage to enzymatic systems and DNA leads to cell death in agreement with Guzman et al. (2012). The results of this study showed that both of the diode laser and silver nanoparticles showed an antibacterial effect, but diode laser showed more effective to remove more of bacterial counts than silver nanoparticles.

Conclusion

The results of the study showed that the diode laser 970 nm has a strong antibacterial with the investigated parameters in comparison to silver nanoparticles; however, the effectiveness of silver nanoparticles in bacterial reduction was acceptable as a less costly method.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

IBM® Corporation, NY, USA.

SPSS®, Inc., an IBM Company.

References

Ahmed M, Sabahalkheir A, Aldebasi Y, Hassan E (2011) Antibacterial influence of Omega diode laser exposure durations on Streptococcus mutans. J Microbiol Antimicrob. 3:136–141

Alabdulmohsen Z, Saad A (2017) Antibacterial effect of silver nanoparticles against Enterococcus faecalis. Saudi Endodontic Journal. 7:29–35

Alfredo E, Marchesan M, Sousa-Neto M, Brugnera-Júnior A, Silva-Sousa Y (2008) Temperature variation at the external root surface during 980-nm diode laser irradiation in the root canal. J. Dent. 36:529–534

Al-habeeb A, Nayif M, Taha M (2013) Antibacterial effects of diode laser and chlorhixidine gluconate on Streptococcus mutans in coronal cavity. WebmedCentral, Res Articles. 10:2–10

Anic I, Tachibana H, Masumoto K, Qi P (1996) Permeability, morphologic and temperature changes of canal dentine walls induced by Nd:YAG, CO2 and argon lasers. Int Endo J. 29:13–22

Anil C, Rakesh K, Shakya V, Luqman S, Simith Y (2017) Antimicrobial efficacy of silver nanoparticles with and without different antimicrobial agents against Enterococcus faecalis and Candida albicans. Dental Hypotheses 8:94–99

Ashofteh K, Sohrabi K, Iranparvar k CN (2014) In vitro comparison of the antibacterial effect of three intra-canal irrigants and diode laser on root canals infected with Enterococcus faecalis. Iran J Microbiol. 6:26–30

Baburao L, Neelkanth B, Vivek H, Sangeeta M (2014) Effect of diode laser on periodontally involved root surfaces: an in vitro environmental scanning electron microscope study. J Dent Lasers. 8:2–7

Barbosa S, Silvana C, Lorenzetti S, Luiz L (2008) High power diode laser in the disinfection in depth of the root canal dentin. Endo. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Path. Oral Rad. 106:68–72

Byström A, Sundqvist G (1981) Bacteriologic evaluation of the efficacy of mechanical root canal instrumentation in endodontic therapy. Eur J Oral Sci. 89:321–328

Camargo S (2011) The antibacterial effects of lasers in endodontics. Laser Endod 48:1–5

Colaco A (2018) Extreme resistance of Enterococcus faecalis and its role in endodontic treatment failure. Prog Med Sci 2:9–13

Dalton B, Ørstavik D, Phillips C, Pettiette M, Trope M (1998) Bacterial reduction with nickel-titanium rotary instrumentation. J Endod. 24(11):763–767

Daming W, Fan W, Kishen A, Gutmann J, Fan B (2014) Evaluation of the antibacterial efficacy of silver nanoparticles against Enterococcus faecalis biofilm. JOE 40:285–290

Duggan J, Sedgley C (2007) Biofilm formation of oral and endodontic Enterococcus faecalis. JOE. 33:815–818

El-Batanouny M, EI-Khodery A, Zaky A (2008) Electronic microscopic study on the effect of diode laser and some irrigants on root canal dentinal wall. Cairo Dent J. 24:421–427

Estrela C, Holland R, De Araújo Estrela C, Alencar A, Sousa-Neto M, Pécora J (2014) Characterization of successful root canal treatment. Braz Dent J 25:3–11

García-Contreras R, Argueta-Figueroa L, Mejía-Rubalcava C, Jiménez-Martínez R, Cuevas-Guajardo S, Sánchez-Reyna P, Mendieta-Zerón H (2011) Perspectives for the use of silver nanoparticles in dental practice. Int Dent J. 61:297–301

Gerek M, Asci S, Yaylali DI (2010) Ex vivo evaluation of antibacterial effects of Nd:YAG and diode lasers in root canals. Biotech Biotech Equip. 24:2031–2034

González-Luna P, Martínez-Castañón G, Zavala-Alonso N, Patiño-Marin N, Niño-Martínez N, Morán-Martínez J, Ramírez-González J (2016) Bactericide effect of silver nanoparticles as a final irrigation agent in endodontics on Enterococcus faecalis: an ex vivo study. J Nanomat 10:1–8

Gutkecht N, Gogswaardt D, Conrads G, Christian A, Chubert C, Lampert F (2000) Diode laser radiation and its bactericidal effect in root canal wall dentin. J Clin Laser Med Sur 18:57–60

Gutnecht N, Franzen R, Meister J, Vanweersch L, Mir M (2005) Temperature evaluation on human teeth root surface after diode laser assisted endodontic treatment. Lasers Med Sci. 20:99–103

Guzman M, Dille J, Godet S (2012) Synthesis and antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Nanomedicine. 8:37–45

Haypek P, Zezell D, Bachmann L, Marques M (2006) Interaction between high power diode laser and dental root surface. Thermal, Morphological and Biocompatibility analysis. J. oral laser App. 6:1–9

Hong-gang W, Yuangang I, Jian I, Guomin S, Jimin W, Tang bao W (2002) Studies on new method for counting living bacterial cell number. J. Microbiol. 29:89–93

Hussey D, Biagioni P, Mccullagh J, Lamey P (1997) Thermo-graphic assessment of heat generated on the root surface during post space preparation. Int. Endod. J. 30(No3):187–190

Johnsrud S. Microbiological examination – total colony number. Mechanical and chemical pulps, paper and paperboard.2002; 6:1-5.

Kaiwar A, Usha H, Meena N, Ashwini P, Murthy C (2013a) The efficiency of root canal disinfection using a diode laser: in vitro study. Indian J Dent Res 24:14–18

Kaiwar A, Usha H, Meena N, Ashwini P, Murthy C (2013b) The efficiency of root canal disinfection using a diode laser: in vitro study. Indian J Dent Res 24:14–18

Krishnan R, Arumugam V, Vasaviah S (2015) The MIC and MBC of silver nanoparticles against Enterococcus faecalis - a facultative anaerobe. J Nanomed Nanotechnol. 6:1–4

Lee B, LinY CJ, Hsieh T, Chen M, Lin C, Lan W (2006) Bactericidal effects of diode laser on Streptococcus mutants after irradiation through different thickness of dentin. Lasers Surg Med. 38:62–69

Monawer A, Abdulkahar I (2016) The in vitro role of diode laser in eradication of Entrococuus Faecalis infection in dental pulp. Eur J Pharm Med Res 3:714–717

Morones J, Elechiguerra J, Camacho A, Holt K, Kouri J, Ramírez J (2005) The bactericidal effect of silver nanoparticles. Nanotechnology. 16:2346–2353

Mortiz A, Schoop U, Goharkhay K, Schauer P, Doertbudak K, Wernisch J, Sperr W (1998) Treatment of periodontal pockets with a diode laser. Lasers Surg Med. 22:302–311

Nair P, Sjögren U, Krey G, Kahnberg K, Sundqvist G (1990) Intraradicular bacteria and fungi in root-filled, asymptomatic human teeth with therapy-resistant periapical lesions: a long-term light and electron microscopic follow-up study. J Endod. 16:580–588

Pendyab C, Tiwari R, Dixit H, Augustine V, Baruah Q, Baruah K (2017) Contemporary apprise on lasers and its a application in dentistry. Int J Oral Health Med Res 4:47-51

Pimpang P, Sutham W, Mangkorntong N, Mangkorntong P, Choopun S (2008) Effect of stabilizer on preparation of silver and gold nanoparticle using grinding method. J Sci. 35:250–257

Radaelli C, Zezell D, Cai S, Antunes A, Gouw-Soares S (2003) Effect of a high power diode laser irradiation in root canals contaminated with Enterococcus faecalis. “In vitro study”. Int Congr Scr 1248:273–276

Rahul H, Mithra H, Kiran H (2014) Penetration of E. faecalis into root cementum cause for reinfection. Annu Res Rev Biol 4:4115–4122

Rai M, Deshmukh S, Ingle A, Gade A (2012) Silver nanoparticles: the powerful nanoweapon against multidrug-resistant bacteria. J Appl Microbiol. 112:841–852

Ramskold L, Fong C, Stromberg T (1997) Thermal effects and antibacterial properties of energy levels required to sterilize stained root canals with an Nd:YAG laser. J Endo. 23:96–100

Ribeiro D, Nogueira G, Antoniazzi J, Moritz A, Zezell D (2007) Effects of diode laser (810 nm) irradiation on root canal walls: thermographic and morphological studies. J. Endod. 33:252–255

Rodrigues C, De Andrade F, De Vasconcelos L, Midena R, Pereira T, Kuga M, Duarte M, Bernardineli N (2018a) Antibacterial properties of silver nanoparticles as a root canal irrigant against Enterococcus faecalis biofilm and infected dentinal tubules. Int Endod J 51:901–911

Rodrigues C, De Andrade F, De Vasconcelos L, Midena R, Pereira T, Kuga M, Duarte M, Bernardineli N (2018b) Antibacterial properties of silver nanoparticles as a root canal irrigant against Enterococcus faecalis biofilm and infected dentinal tubules. Int Endod J 51:901–911

Rodriguez-Chang S, Ramirez-Mora T, Valle-Bourrouet G, Rojas-Campos N, Chavarria-Bolanos D, Montero-Aguilar M (2016) Antibacterial efficacy of a dispersion of silver nanoparticles in citrate medium for the treatment of E. faecalis: in vitro study. Int. J. Dent. Sc. 18:99–107

Rosenberg B, Kemeny G, Switzer R, Hamilton T (1971) Quantitative evidence for protein denaturation as the cause of thermal death. Nature 232:471–473

Scott S (2011) Accuracy of plate counts. J Vaudation Technowgy 17:24–46

Sieuwerts S, De Bok F, Mols E, De Vos W, Van Hylckama V (2008) A simple and fast method for determining colony forming units. Lett Appl Microbiol 47:275–278

Sohrabi K, Sooratgar A, Zolfagharnasab K, Kharazifard M, Afkham F (2016) Antibacterial activity of diode laser and sodium hypochlorite in Enterococcus Faecalis-contaminated root canals. I EJ Iran Endod J 11:8–12

Umana M, Heysselaer D, Tielemans M, Compere P, Zeinoun T, Nammour S (2013) Dentinal tubules sealing by means of diode lasers (810 and 980 nm): a preliminary in vitro study. Photomed Laser Surg 31:1–8

Valera M, Godinho da Silva K, Maekawa L, Carvalho C, Koga-Ito C, Camargo C, Raphael Lima S (2009) Antimicrobial activity of sodium hypochlorite associated with intracanal medication for Candida albicans and Enterococcus faecalis inculated in root canals. J Appl Oral Sci 17:555–559

Weckwerth P, Zapata R, Vivan R, Tanomaru-Filho M, Maliza A, Duarte M (2013) In vitro alkaline pH resistance of Enterococcus faecalis. Braz Dent J 24:474–447

Yeh S, Jain K, Andreana S (2005) Using a diode laser to uncover dental implants in second-stage surgery. Gen Dent 53:414-417

Acknowledgements

All authors are very grateful to the National Research Centre.

Funding

No fund available.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors participated in the development and implementation of the research plan and subsequently wrote it. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors state that they all want to publish this paper in the bulletin of the National Research Centre.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Sadony, D.M., Montasser, K. Evaluation and comparison between the bactericidal effect of diode laser irradiation (970 nm) and silver nanoparticles on Enterococcus faecalis bacterial strain (an in vitro study). Bull Natl Res Cent 43, 155 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42269-019-0188-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42269-019-0188-5