Abstract

Background

Though injury to the inferior epigastric artery (IEA) is reported to be the most common source of hemorrhagic complications from paracentesis, we wish to present our experience involving deep circumflex iliac artery (DCIA) injuries that in our experience is the artery most frequently injured during paracentesis.

Methods

Sixteen patients with clinically significant hemorrhage following paracentesis were referred to our Interventional Radiology service for trans-catheter embolization. Patterns of hemorrhage from diagnostic cross-sectional imaging and subsequent angiographic findings and management were investigated.

Results

8/16 patients (50%) had angiographic evidence of injury to the DCIA and 4/16 patients (25%) had evidence of injury to the IEA, with two of these patients demonstrating hemorrhage from both the DCIA and IEA; 3/16 patients had injuries to subcostal and/or intercostal arteries; while 3/16 patients had negative angiograms. All patients underwent embolization of the identified injured arteries, and empiric embolization was performed of the DCIA and/or IEA in the three patients with negative angiograms. Fourteen of sixteen patients stabilized post embolization, while two patients required a second embolization procedure to achieve hemostasis; all patients were subsequently discharged home in stable condition.

Conclusion

Both the IEA and the lesser known DCIA need to be considered when performing paracentesis and at subsequent angiography for post paracentesis iatrogenic hemorrhage. Knowledge of both of these at-risk abdominal wall arteries may help minimize hemorrhagic complications from paracentesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Paracentesis related iatrogenic hemorrhage necessitating treatment is rare, occurring in 1% of all paracenteses (Mallory and Schaefer 1978; Runyon 1986). Practitioners are taught to needle the peritoneum laterally in the lower quadrants where the largest fluid pockets are located (Thomsen et al. 2006; Sakai et al. 2005). This approach avoids the inferior epigastric artery (IEA) coursing within the rectus sheath, which is reported to be the most commonly injured vessel during paracentesis that results in clinically significant hemorrhage necessitating endovascular treatment (Sobkin et al. 2008). Interestingly, few cases have been reported of paracentesis related bleeding from the deep circumflex iliac artery (DCIA) (Day et al. 2014; Satija et al. 2012; Kang et al. 2012), which in our experience is the most commonly injured artery from paracentesis subsequently identified at angiography. We wish to present these cases, review the anatomy relevant to the inferior epigastric and deep circumflex iliac arteries, and discuss how to possibly minimize the risk of injury from paracentesis to this lesser known artery.

Materials and methods

Our institutional review board approved this retrospective study that includes 16 patients identified through a data mining software (Montage-Nuance Communications, Burlington, MA, USA) who were referred to our interventional radiology service for embolization of hemorrhage after paracentesis between 2007 and 2018. Most patients had clinically indicated diagnostic imaging examinations as part of the work up for suspected hemorrhage. Clinical and procedural data for both paracenteses and subsequent angiographic studies were obtained via the patients’ electronic medical record and departmental picture archival system.

Briefly, patients underwent diagnostic angiography under moderate sedation. Via a transfemoral approach (either ipsi- or contra-lateral, at the discretion of the interventionalist), external iliac arteriography of the ipsilateral side as the suspected site of bleeding from recent paracentesis was performed in standard fashion. A three French micro-catheter was then advanced in co-axial fashion into the specific abdominal wall artery where hemorrhage was identified, and embolization was performed in standard fashion per the operators’ discretion with some combination of polyvinal alcohol particles (355–500 um Contour™ embolization particles, Boston Scientific, Cork, Ireland), Gelfoam®pledgets (Pharmacia UpJohn Company, Kalamazoo, MI, USA), off-label use of liquid Onyx (MicroTherapeutic, Inc., ev3™, Irvine, CA, USA), and/or platinum microcoils. When the angiogram was negative for contrast extravasation or psuedoaneurysm and a high clinical suspicion of active bleed remained, empiric embolization of the arterial supply to the region of interest was performed. Hemostasis was generally obtained by placement of an AngioSeal™ vascular closure device (Terumo Medical Corporation, Somerset, NJ, USA). The patients were monitored on the clinical floor until both hemodynamic status and hemoglobin stabilized.

Results

This study included a total of 16 patients, 11 males and 5 females, with a mean age of 55 years (Table 1). Thirteen patients (82%) had underlying cirrhosis secondary to alcohol (38%), hepatitis C virus (38%), or primary biliary cirrhosis (6%); one patient had ascites secondary to cardiomyopathy (6%), another had ascites secondary to septic shock (6%), and one patient had ascites due to cholangiocarcinoma (6%).

Paracenteses were performed by hospitalists (n = 10, 63%) or interventional radiologists (n = 3, 19%), and in three cases no procedure note was found. The paracenteses were performed under ultrasound guidance in all documented cases, eight cases of right lower quadrant access and five cases of left lower quadrant access. The patients at the time of the paracentesis had an average prothrombin time of 24.2 seeconds (range = 12–43.4), platelet count of 106.6 × 103/μL blood (range = 45–230), and body mass index (BMI) of 28.5 Kg/m2 (range = 19–46). An average of 4.6 L of ascites (range = 1.2–8 L) was collected, with all but two cases documenting a non-sanguineous aspirate. In three cases, prolonged oozing at the puncture site was noted, and manual pressure was applied for 5–10 min at the time of paracentesis.

The average time between paracentesis and diagnosis of bleeding as well as the average time to perform angiography were 0.8 day (range = 0–3) and 3 days (range = 0–15), respectively. The most common presenting symptom was abdominal pain and in some cases was altered mental status with hypotension, with one case requiring a rapid response code activation. All patients received medical management including administration of blood products prior to decision to proceed to angiography.

Fourteen out of sixteen patients had diagnostic computed tomography (CT) prior to angiography, 1 patient had a diagnostic ultrasound only, and 1 patient was transferred emergently to interventional radiology without imaging. Signs of hemorrhage were identified in all imaged patients and included variable findings of abdominal wall hematoma, hemoperitoneum, and/or pseudoanurysm, with or without active extravasation (Fig. 1a, b).

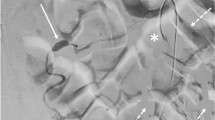

a Axial and b coronal CT images demonstrate ascites with fluid-fluid level suggestive of blood products with active contrast extravasation along the left lateral abdomen (arrows). Subsequent digital subtraction angiography images show extravasation c from an injury to a branch of the left deep circumflex iliac artery (arrow), and d the same patient after coil (arrowhead) and Gelfoam embolization of the vessel indicating successful occlusion of the artery and resolution of hemorrhage

Of the 16 initial angiograms, 8 patients (50%) had angiographic evidence of injury to the DCIA (Fig. 1c, d) and four patients (25%) had evidence of injury to the IEA, with two of these patients demonstrating hemorrhage from both the DCIA and IEA; in three patients, the injured arteries were noted to be subcostal or intercostal arteries, including one patient who had had her DCIA embolized at her first embolization procedure; finally, no evidence of arterial injury could be identified in three patients. In the 13 patients where an injured vessel was identified on initial angiography, trans-catheter embolization was performed of these vessels. Of the three patients without angiographic evidence of arterial injury, empiric embolization of both IEA and DCIA was performed in two patients and only the IEA in one patient. In total, 10 out of the 16 patients had embolization performed of the DCIA.

Fourteen patients (88%) stabilized post embolization, while two patients (12%) who initially had embolization performed of the DCIA required repeat embolization because of continued dropping hemoglobin. In the first case, repeat angiography demonstrated prominent collateral flow from lumbar and intercostal arteries to the paracentesis site, and embolization of these vessels was performed. In the second case, contrast extravasation from the IEA was noted, which was then embolized successfully. There were no documented procedural complications. All patients were subsequently discharged home in stable condition.

Discussion

Bleeding complications from paracenteses are rare, occurring 1% of the time (Runyon 1986). However, these can result in life-threatening hemorrhage and carry significant morbidity and mortality. Patients are frequently coagulopathic due to intrinsic liver disease, as with the majority of the patients in our report.

Proceduralists have been taught to minimize the bleeding risk and maximize fluid acquisition by preferentially targeting the left lower abdominal quadrant based on anatomic landmarks 2–4 cm cephalad and medial to the anterior superior iliac spine which is sufficiently lateral to the rectus sheath to avoid the risk of injury to the IEA (Sakai et al. 2005). Several factors may distort the normal anatomy, thus making these landmarks difficult to determine in everyday practice: 1) In patients with ascites, the abdominal musculature and IEA are stretched laterally (Sharzehi et al. 2014), and 2) With obesity, the body habitus may also obscure anatomic landmarks such as the anterior superior iliac spine, as with many of the patients in our report. However, the increased utilization of ultrasound has allowed proceduralists to target the largest pocket of fluid regardless of anatomic location. It is worth noting that while the supra-pubic, midline approach is still performed by some so as to minimize risk of injury to the IEA, the majority of patients undergoing paracentesis have cirrhosis related portal hypertension, and lacerated varices along the peritoneal surface are relatively common in the peri-umbilical region; approximately one third of hemorrhagic complications from paracentesis may be due to these mesenteric varices (Sharzehi et al. 2014).

Injuries to the IEA have a relatively early presentation compared to injuries of other abdominal wall vessels (such as the DCI and varices) given the formation of a hematoma within the rectus muscle sheath compared to the lateral abdominal wall and the peritoneal cavity (Day et al. 2014; Rimola et al. 2007). Therefore, DCIA bleeding may be more difficult to identify compared to inferior epigastric bleeding, as it less likely to form a palpable abdominal wall hematoma (Day et al. 2014). When this happens, occult hemoperitoneum rather than visible abdominal wall hematoma is the main hemorrhagic feature, and delayed presentation of clinically significant bleeding up to 4 days later may occur and present a diagnostic and management challenge (Arnold et al. 1997). In our series, only 9 of the 16 patients developed hematomas by physical exam or by cross-sectional imaging, and 4 of the 8 patients with angiographically documented injured DCIAs presented with hemoperitoneum alone. Traditionally it has been recommended to follow patients at risk for bleeding after paracentesis closely including serial daily hemoglobin checks for several days (Arnold et al. 1997; Katz et al. 2013). However, this may not be pragmatic in contemporary outpatient practice, as patients are routinely scheduled as outpatients for large volume paracenteses.

The mainstay of treatment is first recognition, followed by medical management, and then embolization for patients not responding to conservative management. To date, the largest report of embolization for post paracentesis bleeding described 19 patients with the IEA as the bleeding source in the majority of their patients, none of whom had evidence of injury to the DCIA (Sobkin et al. 2008). If an infraumbilical approach was taken and an injury to the recannalized paraumbilical vein occurs, arteriography will be negative. In a review of the literature, we were only able to identify five definitive cases of injury to the DCIA from paracentesis (Day et al. 2014; Satija et al. 2012; Kang et al. 2012; Rimola et al. 2007), of which four necessitated embolization procedures (one patient responded to conservative management alone). Other investigators have referenced the DCIA as an unusual culprit in abdominal wall hemorrhage from a variety of etiologies; these include Park et al. (Park et al. 2011) who reported embolizations in 12 patients for abdominal wall hemorrahge, including 11 IEAs and only 1 DCIA, though the authors made no mention as to the etiologies of the bleeds, and Mukind et al. (Mukund et al. 2018) who had 23 patients post paracentesis with mostly IEA injuries, but at least one patient with injury to the DCIA documented at angiography. However, in our experience, DCIA injury is the most commonly injured artery (50%) from paracentesis identified at angiography. As many hemorrhages are managed non-operatively, it is almost certain that the true incidence of injury to the DCIA is significantly underreported.

We hypothesize that in consciously avoiding the IEA, practitioners choose a puncture site that is too lateral along the iliac crest which often cannot be easily palpated through a distended abdomen, and where the DCIA courses, resulting in injury to this vessel. While ultrasound evaluation of the peritoneum is primarily utilized to find the largest fluid pocket, mapping out the IEA with the highest frequency ultrasound transducer possible and palpating the iliac crest prior to paracentesis may help to select an appropriate “middle ground” between the two at-risk arteries (Stone and Moak 2015; Sekiguchi et al. 2013). Additionally, portal-systemic varices should be attempted to be identified and avoided. On thinner patients, the DCIA may even sometimes be identified on ultrasonography (Figs. 2 and 3). However, as both Sobkin (Sobkin et al. 2008) and Mukin (Mukund et al. 2018) have noted, as well as in our own experience, the injured artery is typically a small branch rather than the parent artery.

Anatomic drawing of important anterior abdominal wall arteries superimposed on a healthy volunteer with the right hemi-abdomen demonstrating the course of the arteries obtained by Dopper ultrasound images, see Fig. 2

Limitations of our report included its retrospective nature, small patient group, and bias that only the most symptomatic patients were likely referred to IR with lack of more information regarding the patients with post paracentesis hemorrhage managed only conservatively at our institution over the reported time period.

Conclusion

The most common, albeit rare, complication from paracentesis in this typically coagulopathic patient population is hemorrhage. Our reported cases illustrate that the DCIA needs to be considered alongside the IEA when performing paracentesis and at subsequent angiography for post paracentesis iatrogenic hemorrhage. Knowledge of both of these at-risk abdominal wall arteries may help minimize clinically significant iatrogenic hemorrhage from paracentesis and facilitate subsequent embolization when required.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- DCIA:

-

Deep circumflex iliac artery

- IEA:

-

Inferior epigastric artery

- INR:

-

International normalized ratio

References

Arnold C, Haag K, Blum H, Rossle M (1997) Acute hemoperitoneum after large-volume paracentesis. Gastroenterology 113(3):978–982

Day RW, Huettl EA, Naidu SG, Eversman WG, Douglas DD, O’Donnell ME (2014) Successful coil embolization of circumflex iliac artery Pseudoaneurysms following paracentesis. Vasc Endovasc Surg 48(3):262–266

Kang JW, Kim YD, Hong JS, Kwon JH, Seo HW, Kim SH, Lee JH, Cheon GJ (2012) A case of lateral Abdominal Wall hematoma treated with Transcatheter arterial embolization. Korean J Gastroenterol 59(2):185–188 (article in Korean)

Katz MJ, Peters MN, Wysocki JD, Chakraborti C (2013) Diagnosis and Management of Delayed Hemoperitoneum Following Therapeutic Paracentesis. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 26(2):185–186

Mallory A, Schaefer J (1978) Complications of diagnostic paracentesis in patients with liver disease. JAMA 239(7):628–630

Mukund A, Kumar DPV, Condati NK, Bhadoria AS, Sarin SK (2018) Efficacy and safety of ultrasound guided percutaneous glue embolization in iatrogenic haemorrhagic complications of paracentesis and thoracocentesis in cirrhotic patients. Br J Radiol. https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr.20170259

Park SW, Ko SY, Yoon SY, Choe WH, Yun IJ, Chang S-H, Won JY, Chung HH (2011) Transcatheter arterial embolization for hemoperitoneum: unusual manifestation of iatrogenic injury to abdominal muscular arteries. Abdom Imaging 36(1):74–78

Rimola J, Perendreu J, Falcó J, Fortuño JR, Massuet A, Branera J (2007) Percutaneous arterial embolization in the Management of Rectus Sheath Hematoma. Am J Roentgenol 88(6):W497–W502

Runyon BA (1986) Paracentesis of Ascitic fluid. Arch Intern Med. 146(11):2259

Sakai H, Sheer TA, Mendler MH, Runyon BA (2005) Choosing the location for non-image guided abdominal paracentesis. Liver Int 25(5):984–986

Satija B, Kumar S, Duggal R, Kohli S (2012) Deep circumflex iliac artery Pseudoaneurysm as a complication of paracentesis. J Clin Imag Sci. https://doi.org/10.4103/2156-7514.94022

Sekiguchi H, Suzuki J, Daniels CE (2013) Making Paracentesis Safer. Chest 143(4):1136–1139

Sharzehi K, Jain V, Naveed A, Schreibman (2014) Hemorrhagic complications of paracentesis: a systematic review of the literature. Gastroenterol Res Pract. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/985141

Sobkin PR, Bloom AI, Wilson MW, Laberge JM, Hastings GS, Gordon RL, Brody LA, Sawhney R, Kerlan RK (2008) Massive Abdominal Wall hemorrhage from injury to the inferior epigastric artery: a retrospective review. J Vasc Interv Radiol 19(3):327–332

Stone JC, Moak JH (2015) Feasibility of sonographic localization of the inferior epigastric artery before ultrasound-guided paracentesis. Am J Emerg Med 33(12):1795–1798

Thomsen TW, Shaffer RW, White B, Setnik GS (2006) Videos in Clinical Medicine: Paracentesis. N Engl J Med 355(19):e21

Acknowledgments

None.

Funding

This study was not supported by any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JK wrote the primary draft of this manuscript, MN analyzed and interpreted the patient data and constructed the database, and JS concepted the project design, interpreted the data, and substantially revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Our institutional review board (Linda University Institutional Review Board: Research Protection Programs, reference number: 5170131) approved this retrospective study and waived need for informed consent from patients.

Consent for publication

No individual, identifiable data included in manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kalantari, J., Nashed, M.H. & Smith, J.C. Post paracentesis deep circumflex iliac artery injury identified at angiography, an underreported complication. CVIR Endovasc 2, 24 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42155-019-0068-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42155-019-0068-y